Abstract

Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) has recently been shown to be a prominent cause of respiratory infections in immunocompromised hosts, and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. We report a case of hMPV pneumonia in a lung transplant recipient presenting with respiratory failure and sepsis syndrome. hMPV was diagnosed by polymerase chain reaction, and treated with intravenous ribavirin with a successful outcome.

Lung transplant recipients are at increased risk of respiratory tract infections due to continuous exposure of the allograft to the environment, and decreased mucociliary clearance and lymphatic drainage.1 Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) is a coronavirus that has been isolated from 33% to 64% of symptomatic lung transplant recipients.2, 3, 4 hMPV has now been recognized as a cause of respiratory failure and death in patients with hematologic malignancy and in recipients of bone marrow and solid-organ transplants.5, 6, 7 We report a case of hMPV pneumonia in a lung transplant recipient who was diagnosed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and successfully treated with intravenous ribavirin.

Case Report

A 59-year-old white woman underwent a double-lung transplant in September 2005 for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She received 30 mg alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody) and 1,000 mg methylprednisolone as an induction therapy at the time of transplantation. Her post-operative course was uneventful and she was discharged 10 days after transplantation. Her immunosuppressive regimen at discharge included oral tacrolimus, with a target level of 12 to 15 ng/ml, and 10 mg/day of oral prednisone. She was also prescribed oral voriconazole 200 mg twice daily, oral valganciclovir 450 mg daily and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole at single strength 3 times a week for Aspergillus, cytomegalovirus and Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis, respectively.

The patient did very well clinically and her surveillance bronchoscopies were negative for acute cellular rejection. Six months after transplantation, in April 2006, she presented with a 12-day history of watery diarrhea and abdominal pain. She had also noted mild upper respiratory infection (URI) symptoms similar to her husband’s self-limiting illness the preceding week. Her work-up for Clostridium difficile and cytomegalovirus was negative, and she was started on steroids for possible relapse of Crohn’s disease according to gastroenterology recommendations. This resulted in symptomatic improvement of her abdominal symptoms but she continued to have upper respiratory symptoms. Her persistent respiratory symptoms prompted bronchoscopy and biopsy.

After the procedure, she developed fever, hypotension and respiratory distress requiring endotracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation and pressor support with norepinephrine and vasopressin. She was also started on empiric antibiotic coverage with intravenous cefepime, vancomycin and metronidazole for possible septic shock. Meanwhile, her earlier transbronchial biopsy did not reveal any rejection. Concomitant bronchoalveolar lavage cultures grew light beta-lactamase-negative Haemophilus influenzae and rare Aspergillus niger. The viral shell assay was negative for adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus and parainfluenza virus.

She continued to require pressor support with increasing an oxygen requirement. Chest radiograph revealed diffuse bilateral infiltrates. Owing to her worsening clinical condition, hMPV PCR was requested from the nasopharyngeal swab and previously stored bronchoalveolar lavage. Real-time PCR for hMPV was performed as reported previously,8 and both samples were positive. The patient was subsequently started on inhaled ribavirin, but she continued to be in shock and developed acute respiratory distress syndrome.

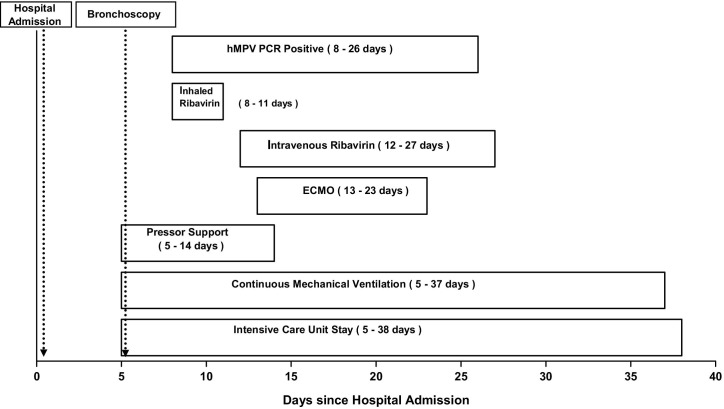

She was started on venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and was switched from inhaled to intravenous (IV) ribavirin. On Day 1, she was given a loading dose of 33 mg/kg IV, and then from Day 2 to Day 5 she received 16 mg/kg IV daily. Later she was continued on 8 mg/kg IV daily. She was treated with IV ribavirin until hMPV PCR from bronchoalveolar lavage became negative (Day 15 of IV ribavirin therapy). She showed marked clinical improvement and was taken off ECMO, pressors and ventilatory support after 10 days of initiation of IV ribavirin therapy (Figure 1). The patient was discharged 35 days after respiratory failure to a rehabilitation facility and continued to do well. Her repeat biopsy 1 month after completion of IV ribavirin did not show any evidence of pneumonia or rejection. During the course of therapy with ribavirin she had a transient low white cell count and anemia, which recovered completely after completion of treatment. Her repeat hMPV PCR assessments, done starting at 3 months after treatment, remain negative.

Figure 1.

Course of treatment for our patient with hMPV.

Discussion

Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) is a recently discovered, community-acquired seasonal respiratory pathogen. Although the virus was initially detected in respiratory samples in 2001 in The Netherlands, retrospective analyses of stored samples has implicated it as a cause of pulmonary disease in humans for the last 50 years in Europe and North America.9 We have reported the first case of hMPV pneumonia in a lung transplant recipient with successful outcome associated with IV ribavirin therapy.

hMPV is a negative-sense, non-segmented RNA paramyxovirus.9 It shares seasonal variation with respiratory syncytial virus, with most cases diagnosed in late winter and early spring.10 hMPV can cause both symptomatic and asymptomatic upper and lower respiratory tract disease, although a lower respiratory tract disease is more likely at extreme ages.10 Clinical features of hMPV infection at presentation are usually of upper respiratory tract infection, which can progress to respiratory failure (requiring mechanical ventilation), culture-negative sepsis syndrome and pulmonary hemorrhage.6 This is possibly due to increased cytokine production, specifically interleukin-8 (IL-8) and interferon-alpha.11 Persistent asymptomatic presence of hMPV in the respiratory tract has been demonstrated in stem cell transplant recipients, although the significance and long-term outcome have not yet been determined.12

In lung transplant recipients, data on hMPV infection are currently limited. hMPV has been shown to be present in both symptomatic and asymptomatic recipients, and its role in acute complications, such as acute allograft rejection, and long-term outcomes, such as bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, has been inconclusively investigated.2, 3, 8 Moreover, no successful systemic anti-viral regimen for severe lower respiratory tract disease has been determined.

Ribavirin is a synthetic guanosine nucleoside analog, which acts by inhibiting viral RNA polymerase. It has been used successfully for respiratory syncytial virus infection in lung transplant recipients.13 It has significant in vitro activity against hMPV and, in animal models, has been shown to decrease hMPV replication and inflammation in the lung.14 Data from immunocompromised hosts regarding treatment of hMPV with ribavirin are limited and use of inhaled ribavirin has not been successful.6

Real-time PCR has been used widely with reliability for detection of hMPV. In a comparative evaluation, amplification of the N gene, which was used in our real-time PCR, was found to be particularly suitable for diagnosis of hMPV.15

In our case the patient may have acquired the hMPV infection by contact with her husband, as he had URI symptoms in the preceding week. Her husband recovered but she developed severe respiratory illness, perhaps due to her immunocompromised status and introduction of hMPV to the lower respiratory tract as a result of the bronchoscopy and transbronchial biopsy procedure. Alternatively, acute worsening of respiratory symptoms after bronchoscopy may be attributed to the presence of H influenzae in the bronchoalveolar lavage of this patient. However, this seems unlikely for several reasons. First, H influenzae usually colonizes the respiratory tracts of patients with chronic lung disease and isolation of this organism is not always associated with active disease.16, 17 Second, clinical presentation with septic shock is usually seen in younger patients with splenectomy or functional asplenia.18 Patients with H influenzae septic shock, as with other systemic bacterial infections, typically exhibit leukocytosis, bandemia and positive blood cultures.19 All of the aforementioned risk factors and features were absent in our patient. Third, the isolate was beta-lactamase-negative and sensitive to cefepime. The patient reported here continued to deteriorate clinically despite being on appropriate antibiotic coverage, and improvement occurred only after initiation of a systemic anti-viral agent.

Similarly, detection of hMPV in bronchial secretion may suggest that it is a colonizer. However, we believe this is less likely because our patient developed a respiratory syndrome with typical culture-negative sepsis syndrome, which only improved after administration of ribavirin. Her initial worsening of respiratory symptoms on inhaled ribavirin was due to the development of bronchospasm usually noted with this route and evidenced by increased peak airway pressure. The patient was started on ribavirin owing to its potential activity against hMPV. Use of intravenous ribavirin was clearly associated with improvement and subsequent recovery of this patient. Although further well-defined studies are required to determine the incidence of hMPV in transplant recipients with acute respiratory illness, and to establish the optimal treatment of hMPV in lung transplant recipients, our case suggests the use of intravenous ribavirin as an option in cases of hMPV pneumonia in immunocompromised hosts.

References

- 1.Chan K.M. Approach towards infectious pulmonary complications in lung transplant recipients. In: Singh N., Aguado J.M., editors. Infectious complications in transplant patients. Kluwer Academic; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2001. pp. 149–175. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar D., Erdman D., Keshavjee S. Clinical impact of community-acquired respiratory viruses on bronchiolitis obliterans after lung transplant. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2031–2036. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerna G., Vitulo P., Rovida F. Impact of human metapneumovirus and human cytomegalovirus versus other respiratory viruses on the lower respiratory tract infections of lung transplant recipients. J Med Virol. 2006;78:408–416. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larcher C., Geltner C., Fischer H., Nachbaur D., Muller L.C., Huemer H.P. Human metapneumovirus infection in lung transplant recipients: clinical presentation and epidemiology. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1891–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams J.V., Harris P.A., Tollefson S.J. Human metapneumovirus and lower respiratory tract disease in otherwise healthy infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:443–450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Englund J.A., Boeckh M., Kuypers J. Brief communication: fatal human metapneumovirus infection in stem-cell transplant recipients. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:344–349. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-5-200603070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards A., Chuen J.N., Taylor C., Jackson R., Toms G., Kavanagh D. Acute respiratory infection in a renal transplant recipient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:2848–2850. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dare R., Sanghavi S., Bullotta A. Diagnosis of human metapneumovirus infection in immunosuppressed lung transplant recipients and children evaluated for pertussis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:548–552. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01621-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Hoogen B.G., van Doornum G.J., Fockens J.C. Prevalence and clinical symptoms of human metapneumovirus infection in hospitalized patients. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1571–1577. doi: 10.1086/379200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boeckh M., Erard V., Zerr D., Englund J. Emerging viral infections after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9(suppl 7):48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrero-Plata A., Baron S., Poast J.S., Adegboyega P.A., Casola A., Garofalo R.P. Activity and regulation of alpha interferon in respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus experimental infections. J Virol. 2005;79:10190–10199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10190-10199.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debiaggi M., Canducci F., Sampaolo M. Persistent symptomless human metapneumovirus infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:474–478. doi: 10.1086/505881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glanville A.R., Scott A.I., Morton J.M. Intravenous ribavirin is a safe and cost-effective treatment for respiratory syncytial virus infection after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:2114–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wyde P.R., Chetty S.N., Jewell A.M., Boivin G., Piedra P.A. Comparison of the inhibition of human metapneumovirus and respiratory syncytial virus by ribavirin and immune serum globulin in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2003;60:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(03)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cote S., Abed Y., Boivin G. Comparative evaluation of real-time PCR assays for detection of the human metapneumovirus. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3631–3635. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3631-3635.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy T.F. Haemophilus influenzae in chronic bronchitis. Semin Respir Infect. 2000;15:41–51. doi: 10.1053/srin.2000.0150041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moller L.V., Regelink A.G., Grasselier H., Dankert-Roelse J.E., Dankert J., van Alphen L. Multiple Haemophilus influenzae strains and strain variants coexist in the respiratory tract of patients with cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1388–1392. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen K., Singer D.B. Asplenic–hyposplenic overwhelming sepsis: postsplenectomy sepsis revisited. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2001;4:105–121. doi: 10.1007/s100240010145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zacharisen M.C., Watters S.K., Edwards J. Rapidly fatal Haemophilus influenzae serotype f sepsis in a healthy child. J Infect. 2003;46:194–196. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2002.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]