Abstract

The antigen recognition by the host immune system is a complex biochemical process that requires a battery of enzymes. Cathepsins are one of the enzyme superfamilies involved in antigen degradation. We observed the up-regulation of catfish cathepsin H and L transcripts during the early stage of Edwardsiella ictaluri infection in preliminary studies, and speculated that cathepsin H and L may play roles in infection. We identified, sequenced and characterized the complete channel catfish cathepsin H and L cDNAs, which comprised 1415 and 1639 nucleotides, respectively. The open reading frames of cathepsin H appeared to encode a protein of 326-amino acid residues, which that of cathepsin L encoded a protein of 336 amino acids. The degree of conservation of the channel catfish cathepsin H and L amino acid sequences in comparison to other species ranged from 61% to 77%, and 67% to 85%, respectively. The catalytic triad and substrate binding sites are conserved in cathepsin H and L amino acid sequences. The cathepsin L transcript was expressed in all tissues examined, while the cathepsin H was expressed in restricted tissues. These results provide important information for further exploring the roles of channel catfish cathepsins in antigen processing.

Keywords: Channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus, Cathepsin H, Cathepsin L, CTSH, CTSL

The recognition of an antigen by the host immune system involves a complex biochemical process, including intracellular protein degradation to generate antigenic peptides for presentation [1], [2], [3]. This degradation requires a battery of enzymes inside cells. Cathepsins are one of the enzyme superfamilies involved in regulation of antigen presentation [4], [5].

Cathepsins are lysosomal cysteine proteases of the papain family [6], [7], [8], [9]. They are synthesized as an inactive prepropeptide form in the rough endoplasmic reticulum, and activated autocatalytically or by other proteases to become active enzymes [6], [7], [8], [9]. Currently, there are more than 10 members in the human cathepsin family [10]. We are interested in cathepsins H, L and S (CTSH, CTSL and CTSS, respectively), because we observed that these channel catfish cathepsins were induced and up-regulated in the early stage of Edwardsiella ictaluri infection in channel catfish ovary cells (ATCC CRL-2772) [Yeh and Klesius, unpublished data], leading us to speculate that these cathepsins may play critical roles in infection.

In the mouse immune system, CTSL (E.C. 3.4.22.15) activity has been detected in cortical thymic epithelial cells, where CTSL degrades the invariant chain of MHC class II in the late stages of development and produces MHC class II peptides for CD4T cell selection [4], [5], [11]. A recent in vitro study demonstrated that CTSL is required for Toll-like receptor 9 responses to microbial DNA [12]. Also, CTSL has been implicated in microbial pathogenesis. Simmon et al. [13] showed that CTSL is needed for cleavage of the spike glycoprotein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in endosomes for viral entry. Chandran et al. [14] also showed that CTSL plays an assistant role in Ebola virus infection. CTSH (E.C. 3.4.22.16), first isolated from rat liver [15], is a potent lysosomal cysteine aminopeptidase in the cathepsin family [6], [8]. In physiological states, CTSH is required for lung development [16], [17].

Our interest in gene expression in infectious diseases prompted us to clone and characterize these channel catfish cathepsin cDNAs. We had previously characterized channel catfish CTSS cDNA [18]. In this communication, we report the isolation, characterisation and expression of channel catfish CTSH and CTSL cDNAs.

Channel catfish (NWAC103 strain) were used in this study. Animal usage was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Aquatic Animal Health Research Unit. Prior to aseptic tissue excision, the catfish were euthanized by immersion in tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222) as per the Guidelines of the Use of Fish in Research [19]. Gills, skin, brain, spleen, hepatopancreas, intestine and head kidneys were collected, and each tissue was immersed in 1 ml of TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH).

Total RNA from tissues was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions as described previously [20], [21]. After total RNA isolation, CTSH and CTSL cDNAs were generated by rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) by using a GeneRacer kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers for PCR amplification are listed in Table 1 . The PCR products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and cloned into the pSC-A cloning vector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The ligated plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli by heat-shock. After culture enrichment at 37 °C in S.O.C. medium, the cells were streaked on LB plates containing 30 μg/ml of kanamycin and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Colonies were randomly selected and cultured in WU medium.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

| GeneRacer 5′Primer (Invitrogen) | Forward | 5′-CGACTGGAGCACGAGGACACTGA-3′ |

| GeneRacer 3′Primer (Invitrogen) | Reverse | 5′-GCTGTCAACGATACGCTACGTAACG-3′ |

| CatH-39F | Forward | 5′-TCATGCCGTGCTTGCTGTGGGTTATG-3′ |

| CatH185F | Forward | 5′-CCGAGGAGAACGGCACTCCCTACTGG-3′ |

| CatH64R | Reverse | 5′-CATAACCCACAGCAAGCACGGCATGA-3′ |

| CatH-FF | Forward | 5′-CTCGGATCCATGAAAATACTTATTGTAACTGTTGCAT-3′ |

| CatL-4F | Forward | 5′-GCACTCGCTGGGCAAGCACAGTTACC-3′ |

| CatL-16F | Forward | 5′-CAAGCACAGTTACCGCCTGGCAATGA-3′ |

| CatL-123F | Forward | 5′-GGCCCCAAGCAAGTTGGACTGGAGAG-3′ |

| CatL-355F | Forward | 5′-CAGCTGGAGTGAACAGTGGGGCAACA-3′ |

| CatL-41R | Reverse | 5′-TCCTCATGGGGCATGTCACCAAAGTG-3′ |

| CatL-129R | Reverse | 5′-TGGGGCCTCCAGAAAGTTAGGCTCCA-3′ |

The DNA sequencing reactions were carried out at the USDA ARS MidSouth Genomics Laboratory with an ABI 3730xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the BigDye terminator v.3.1 chemistry. More than 10 clones of each PCR product were sequenced on both strands. Chromatograms were edited and trimmed to remove the vector sequences by using Phred and Lucy software [22], [23], [24]. Amino acid sequences were deduced from nucleic acid sequences by using Transeq software [25] and aligned with other cathepsin amino acid sequences by using ClustalW2 [26] (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/services/index.html). The SignalP 3.0 server [27] and ExPASy server [28] were used to analyze the cathepsin signal peptides and N-glycosylation sites, respectively.

RT-PCR assays for CTSH and CTSL gene transcripts in channel catfish tissues were performed by a two-step procedure routinely used in our laboratory [20], [21]. Primers used are listed in Table 1. The amplified products were analyzed in 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. No reverse transcriptase or template added in reactions was included in experiments to ensure that no amplification was from residual genomic DNA. Images were recorded by a KODAK Gel Logic 440 Imaging System and processed with Adobe Photoshop (v. 7.0.1., Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA).

In a preliminary study, channel catfish CTSH and CTSL expressed sequence tags were identified by subtractive suppression hybridization [Yeh and Klesius, unpublished data]. Based on these sequences, cDNAs to both CTSH and CTSL transcripts were, with the RACE method [29], further sequenced and characterized. The complete sequences of channel catfish CTSH and CTSL cDNAs consisted of 1415 and 1639 nucleotides, respectively, (GenBank accession numbers EU915298 for CTSH and EU915299 for CTSL). Analysis of both sequences revealed that each had an open reading frame (ORF) with the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTR). Like mammalian mRNA, three feature sequences of mRNA, instability motifs, polyadenylation signal sequences and polyadenylation tails, were found in 3′-UTR of CTSH and CTSL sequences (Sequences not shown).

The ORF of channel catfish CTSH cDNA appears to encode a 326-amino acid peptide with a calculated molecular weight of 36.6 kDa. In addition, the deduced CTSH amino acid sequence has three potential N-glycosylation sites at the Asn96, Asn223 and Asn267 residues. For CTSL cDNA, the ORF appears to encode a 336 amino acid peptide with a calculated molecular weight of 38.1 kDa, and a potential N-glycosylation site at the Asn223 residue. This N-glycosylation may be important for transportation of cathepsins into lysosomes [30].

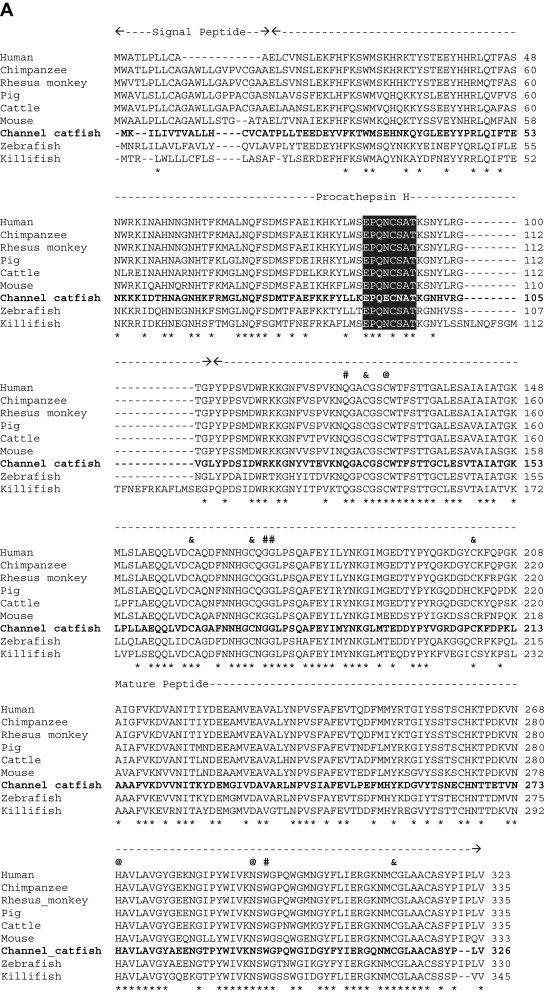

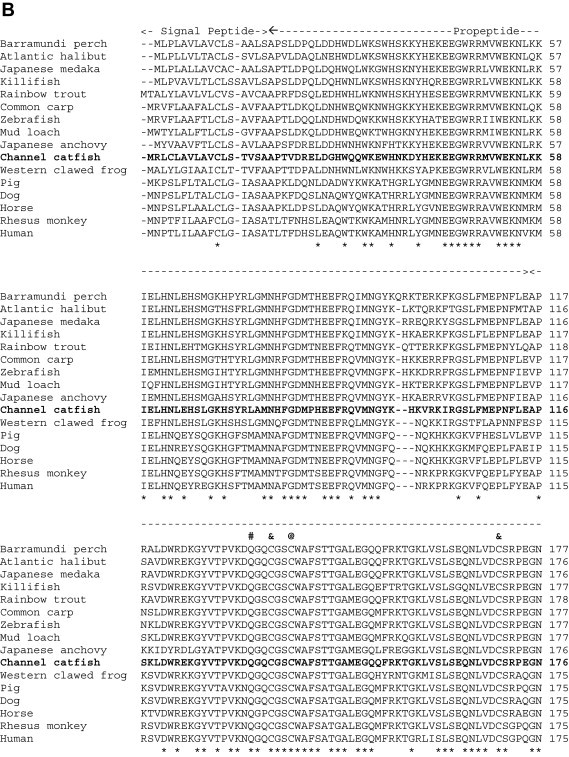

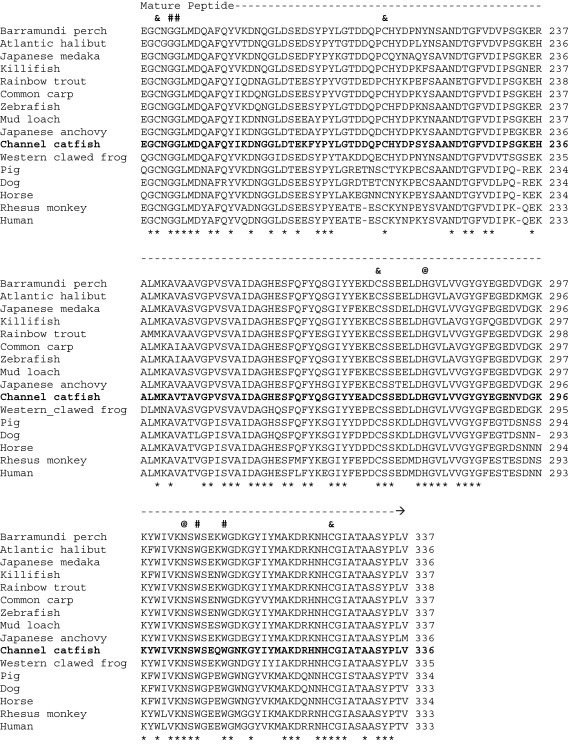

When the predicted channel catfish CTSH and CTSL amino acid sequences were compared with those from other species deposited in the GenBank database, we found that the degree of conservation of CTSH among species ranged from 61% (vs. mouse) to 77% (vs. zebrafish), and that of CTSL was from 67% (vs. human) to 85% (vs. common carp) (Fig. 1 ). Based on mammalian CTSH and CTSL studies [31], [32], the channel catfish CTSH and CTSL amino acid sequences could be structurally divided into three domains: (1) a signal peptide at the amino terminus, (2) a propeptide domain, and (3) a mature peptide at the carboxyl terminus (Fig. 1). Other conserved features in both CTSH and CTSL mature peptides include (denoted as residue number for CTSH/CTSL, respectively): (1) the catalytic triad at Cys134/139, His274/279 and Asn294/303 residues, (2) potential substrate binding sites at Gln128/133, Gly176–177/181–182, Trp296/305 and Trp300/309 residues, and (3) five potential cysteine disulfide linkage sites at 131, 165, 174, 207and 315 in CTSH, and 136, 170, 179, 213, 272 and 325 in CTSL (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ) [31], [33]. In addition, the interspersed sequence (Glu, Arg, [Phe/Trp], Asn, Ile and Asn) was conserved in the propeptide of channel catfish CTSH and CTSL [33], [34].

Fig. 1.

Alignment of the channel catfish CTSH (A) and CTSL (B) amino acid sequences with those from other species deposited in GenBank. Species and the corresponding GenBank accession numbers are as follows: (A) CTSH: cattle, NP_001029557; channel catfish, EU915298; chimpanzee, XP_001153217; human, NP_683880; killifish, AAO64473; mouse, AAH06878; pig, NP_999094; rhesus monkey, XP_001108862; and zebrafish, NP_997853. (B) CTSL: Atlantic halibut, ABJ99858; Barramundi perch, ABV59078; channel catfish, EU915299; common carp, BAD08618; dog, NP_001003115; horse, XP_001494409; human AAH12612; Japanese anchovy, BAC16538; Japanese medaka, NP_001098156; killifish, AAO64471; mud loach, ABQ08058; pig, NP_999057; rainbow trout, NP_001117777; rhesus monkey, XP_001086024; western clawed frog, NP_001004869; and zebrafish, CAN88536. Gaps were introduced in the sequences indicated by hyphens (-). Identical amino acids among species are denoted by asterisks (*) beneath the sequences. The potential catalytic sites, substrate binding sites and disulfide linkage sites are indicated as at signs (@), pound signs (#) and ampersands (&), respectively, above the sequences.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the channel catfish CTSH, CTSL and CTSS amino acid sequences. Three structural domains of the cathepsins are indicated as italic, boldface and regular letters for signal peptide, prodomain and mature peptide, respectively. Identical amino acids among cathepsins are denoted by asterisks (*) beneath the sequences. The potential catalytic sites, substrate binding sites and disulfide linkage sites are indicated as at signs (@), pound signs (#) and ampersands (&), respectively, above the sequences. GenBank accession numbers are as follows: CTSH, EU915298; CTSL, EU915299; and CTSS, EU732711[18].

Gunčar et al. [32] demonstrated that an octapeptide (Glu91–Pro92–Gln93–Asn94–Cys95–Ser96–Ala97–Thr98) in the propeptide region of the porcine CTSH links to the mature peptide and is responsible for the CTSH aminopeptidase activity. As seen in Fig. 1A (shaded area), this octapeptide is conserved among the species examined except for channel catfish. Glu94 and Asn96 replace Asn94 and Ser96 in channel catfish, respectively. Whether these differences will affect its function in aminopeptidase activity remains to be determined.

In a recent study, Tingaud-Sequeira and Cerda [33] found that the zebrafish CTSL has three isoforms (CTSLa, CTSLb and CTSLc). The channel catfish CTSL shows high homology with the zebrafish CTSLa isoform. Whether channel catfish has other CTSL isoforms is unknown.

To compare the relatedness of the three known channel catfish cathepsins, the amino acid sequences of CTSH, CTSL, and CTSS were aligned using ClustalW2 software [26]. The analysis showed little conservation among the three cathepsins of channel catfish (Fig. 2). However, the catalytic, binding, and disulfide linkage sites are all conserved (Fig. 2). This result is in agreement with the characteristics of the cathepsin family [10].

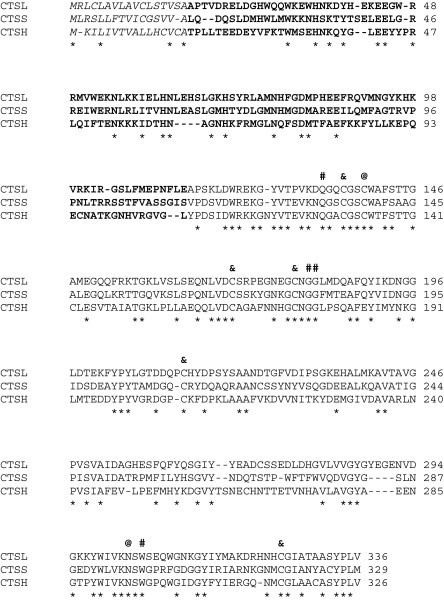

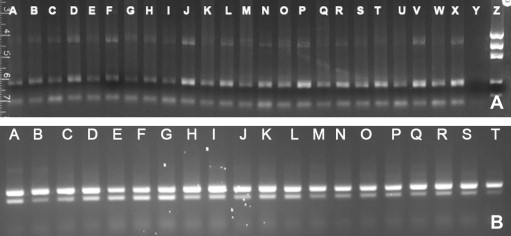

To determine the expression profile of the CTSH and CTSL gene transcripts in various channel catfish tissues, a two-step RT-PCR was used. The amplified CTSH, CTSL and β-actin fragments had 844, 154 and 210 nucleotides, respectively. As seen in Fig. 3 A, the CTSH transcript was detected at a high level in intestine (n = 4) and gill (n = 3), but barely in other tissues, suggesting that CTSH is constitutively expressed in restricted tissues. This phenomenon has also been reported in other species [35], [36]. Its role in the innate immune responses is currently under investigation. On the other hand, the CTSL transcript was expressed in all tissues of fish examined (Fig. 3B). This result is in agreement with the notion that the CTSL transcript is ubiquitous in animal tissues [6]. Reactions without RT or template did not show amplification.

Fig. 3.

Expression of CTSH (A) and CTSL (B) transcripts in channel catfish tissues. Amplified RT-PCR fragments were analyzed on 2% agarose gels. (A) CTSH: spleen (lanes A, G, M and S), head kidney (lanes B, H, N and T), liver (lanes C, I, O and U), intestine (lanes D, J, P and V), skin (lanes E, K, Q and W), gill (lanes F, L, R and X), no template control (lane Y), and Precision Molecular Mass Ruler DNA ladders (lane Z, 1000 bp, 700 bp, 500 bp, 200 bp and 100 bp, respectively; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA). The sizes of CTSH (upper band) and β-actin (lower band) products were 844 bp and 210 bp, respectively. (B) CTSL: spleen (lanes A and B), head kidney (lanes C–E), liver (lanes F–H), intestine (I–K), skin (L–O), and gill (lanes P–T). The sizes of CTSL (lower band) and β-actin (upper band) products were 154 bp and 210 bp, respectively.

In conclusion, channel catfish CTSH and CTSL transcripts were identified, sequenced, characterized, and tissue expression profile determined. These results provide critical information for further elucidating antigen processing in channel catfish. Experiments for catfish cathepsin gene transcript expression in E. coli and production of polyclonal antibodies against these proteins are underway.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mrs. Dorothy B. Moseley of USDA ARS Aquatic Animal Health Research Unit in Auburn, AL for excellent technical support, and Dr. Brian E. Scheffler and his Bioinformatics Group at the USDA ARS MidSouth Genomics Laboratory in Stoneville, MS for sequencing and bioinformatics. We also thank Dr. Thomas L. Welker (USDA ARS Aquatic Animal Health Research Unit) and Dr. Vicky van Santen (Auburn University, Auburn, AL) for critical comments on this manuscript.

This study was supported by the USDA Agricultural Research Service CRIS project no. 6420-32000-020-00D. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this paper is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

References

- 1.Allen P.M., Babbitt B.P., Unanue E.R. T-cell recognition of lysozyme: the biochemical basis of presentation. Immunol Rev. 1987;98:171–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer D.F., Linderman J.J. The relationship between antigen concentration, antigen internalization, and antigenic complexes: modeling insights into antigen processing and presentation. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:55–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watts T.H., McConnell H.M. Biophysical aspects of antigen recognition by T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1987;5:461–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.05.040187.002333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsing L.C., Rudensky A.Y. The lysosomal cysteine proteases in MHC class II antigen presentation. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:229–241. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Honey K., Rudensky A.Y. Lysosomal cysteine proteases regulate antigen presentation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:472–482. doi: 10.1038/nri1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brix K., Dunkhorst A., Mayer K., Jordans S. Cysteine cathepsins: cellular roadmap to different functions. Biochimie. 2008;90:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turk B., Stoka V. Protease signaling in cell death: caspases versus cysteine cathepsins. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2761–2767. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turk V., Turk B., Turk D. Lysosomal cysteine proteases: facts and opportunities. EMBO J. 2001;20:4629–4633. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turk B., Turk D., Turk V. Lysosomal cysteine proteases: more than scavengers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:98–111. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rawlings N.D., Morton F.R. The MEROPS batch BLAST: a tool to detect peptidases and their non-peptidase homologues in a genome. Biochimie. 2008;90:243–259. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakagawa T., Roth W., Wong P., Nelson A., Farr A., Deussing J. Critical role in Ii degradation and CD4 T cell selection in the thymus. Science. 1998;280:450–453. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsumoto F., Saitoh S., Fukui R., Kobayashi T., Tanimura N., Konno K. Cathepsins are required for Toll-like receptor 9 responses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;367:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.12.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons G., Gosalia D.N., Rennekamp A.J., Reeves J.D., Diamond S.L., Bates P. Inhibitors of cathepsin L prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11876–11881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505577102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandran K., Sullivan N.J., Felbor U., Whelan S.P., Cunningham J.M. Endosomal proteolysis of the Ebola virus glycoprotein is necessary for infection. Science. 2005;308:1643–1645. doi: 10.1126/science.1110656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirschke H., Langner J., Wiederanders B., Ansorge S., Bohley P., Broghammer U. Intracellular protein breakdown: VII. Cathepsin L and H; two new proteinases from rat liver lysosomes. Acta Biol Med Ger. 1976;35:285–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guttentag S., Robinson L., Zhang P., Brasch F., Bühling F., Beers M. Cysteine protease activity is required for surfactant protein B processing and lamellar body genesis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:69–79. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0111OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lü J., Qian J., Keppler D., Cardoso W.V. Cathepsin H is an Fgf10 target involved in Bmp4 degradation during lung branching morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22176–22184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeh H.-Y., Klesius P.H. Molecular cloning, sequencing and characterisation of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus, Rafinesque 1818) cathepsin S gene. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2008;126:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nickum J.G., Bart H.L., Jr., Bowser P.R., Greer I.E., Hubbs C., Jenkins J.A. American Fisheries Society; Bethesda, Maryland: 2004. Guidelines for the use of fishes in research. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh H.-Y., Klesius P.H. Complete structure, genomic organization, and expression of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus, Rafinesque 1818) matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72:702–714. doi: 10.1271/bbb.70579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeh H.-Y., Klesius P.H. Channel catfish, Ictalurus punctatus, cyclophilin A and B cDNA characterisation and expression analysis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2008;121:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewing B., Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 1998;8:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ewing B., Hillier L., Wendl M.C., Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 1998;8:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li S., Chou H.-H. LUCY (2): an interactive DNA sequence quality trimming and vector removal tool. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2865–2866. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice P., Longden I., Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–277. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larkin M.A., Blackshields G., Brown N.P., Chenna R., McGettigan P.A., McWilliam H. ClustalW and ClustalX version 2. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bendtsen J.D., Nielsen H., von Heijne G., Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M.R., Appel R.D. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In: Walker J.M., editor. The proteomics protocols handbook. Humana Press; 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frohman M.A., Dush M.K., Martin G.R. Rapid production of full-length cDNAs from rare transcripts: amplification using a single gene-specific oligonucleotide primer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:8998–9002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.8998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi G.-P., Munger J.S., Meara J.P., Rich D.H., Chapman H.A. Molecular cloning and expression of human alveolar macrophage cathepsin S, an elastinolytic cysteine protease. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7258–7262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coulombe R., Grochulski P., Sivaraman J., Ménard R., Mort J.S., Cygler M. Structure of human procathepsin L reveals the molecular basis of inhibition by the prosegment. EMBO J. 1996;15:5492–5503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunčar G., Podobnik M., Pungerčar J., Štrukelj B., Turk V., Turk D. Crystal structure of porcine cathepsin H determined at 2.1 Å resolution: location of the mini-chain C-terminal carboxyl group defines cathepsin H aminopeptidase function. Structure. 1998;6:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tingaud-Sequeira A., Cerda J. Phylogenetic relationships and gene expression pattern of three different cathepsin L (Ctsl) isoforms in zebrafish: ctsla is the putative yolk processing enzyme. Gene. 2007;386:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karrer K.M., Peiffer S.L., DiTomas M.E. Two distinct gene subfamilies within the family of cysteine protease genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3063–3067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kominami E., Tsukahara T., Bando Y., Katunuma N. Distribution of cathepsins B and H in rat tissues and peripheral blood cells. J Biochem. 1985;98:87–93. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lafuse W.P., Brown D., Castle L., Zwilling B.S. IFN-γ increases cathepsin H mRNA levels in mouse macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:663–669. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]