Abstract

Objectives

To assess if a knowledge gap exists in the correct use of face masks, and to explore the correlations between knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the use of face masks among outpatients and their caregivers in an outpatient clinic in Hong Kong.

Study design

Cross-sectional study.

Methods

Outpatients and their caregivers who were present at an outpatient setting in Hong Kong were invited to participate in this survey. All participants were asked to complete a self-administered closed-ended questionnaire about their knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the use of face masks. Data were described using descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients.

Results

Among the 399 respondents, 52% knew the correct steps in wearing a face mask, and their attitudes toward face masks were generally positive. Further analyses showed that respondents were more likely to wear a face mask at a clinic than in a public place or at home. Moreover, respondents were more likely to wear a face mask to protect others against influenza-like illness (ILI) than for self-protection. There was low to moderate correlation between attitudes and practices (correlation coefficient 0.26, P < 0.05).

Conclusions

This study identified a knowledge gap in the correct use of face masks among outpatients and their caregivers; attitudes and practices regarding the use of face masks were generally positive, but correlation was not high. It is recommended that public health education campaigns should tailor efficient programmes to combat ILI transmission among outpatient clinic populations by improving knowledge about the correct use of face masks.

Keywords: Face mask, Influenza-like illness, Hospital transmission

Introduction

In light of the recent severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and H1N1 epidemics, the World Health Organization (WHO) has advocated for the use of non-pharmaceutical public health interventions as the global supplies of vaccines and antiviral agents are limited and not easily accessible.1 Face masks have been a popular public health intervention used for self-protection against influenza-like illness (ILI), and to prevent transmission between sick and healthy individuals. Many countries such as the USA, Australia and France have already included the use of face masks in their pandemic plans.2, 3

Influenza is primarily spread through person-to-person contact via large droplets produced by breathing, talking, coughing or sneezing. As a result, a face mask works by providing a physical barrier against the potentially infectious droplets. Recent studies have concluded that the use of face masks reduces the reproduction number of the virus, which could help delay or possibly contain an influenza pandemic.4 In 2010, Aiello et al. found that there was a 10–50% reduction in the spread of ILI due to the use of face masks and hand hygiene.5 These conclusions were all drawn from the fact that the face masks were worn correctly. WHO states that wearing a mask incorrectly may actually increase, rather than decrease, the rate of transmission.6

The correct use of face masks is particularly important in Hong Kong as the use of face masks is prevalent. Studies have found that 88.8% of participants wore face masks when they had ILI, and 21.5% reported wearing face masks regularly in public.7 A study by Lau et al. found that the Hong Kong public were likely to adopt self-protective behaviors such as using face masks in public places.8 Lau et al. concluded that in the event of a future respiratory illness outbreak, the Hong Kong public would be likely to adopt self-protective behaviors which may help to contain the spread of the virus in the community.9 Several studies in Hong Kong and elsewhere have investigated the prevalence of facemask use.8, 9, 10 However, no studies have investigated the correct use of face masks either in Hong Kong or internationally.

It is important to assess whether there is a knowledge gap in the correct use of face masks, as incorrect practice may hinder their effectiveness. The Hong Kong outpatient setting was chosen as the study population because previous case studies have indicated that healthcare settings are a major source of ILI infection.9 Hospital waiting areas are prime areas for the transmission of airborne infections, because many people are gathered in a confined area, some of whom may have medical conditions that make them vulnerable to infection. Relative to the general population, those who are in an outpatient clinic may experience higher levels of exposure to ILI and, therefore, it is important for both outpatients and their caregivers to wear face masks in order to prevent transmission and for self-protection. The results of this study will help in tailoring a more efficient programme to combat ILI transmission in primary care outpatient settings. This study aimed to assess if a knowledge gap exists in the use of face masks for both subjects seeking medical consultation and their caregivers in an outpatient setting in Hong Kong, and to explore correlations between knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the use of face masks.

Methods

This study was conducted at the Family Medicine Training Centre, Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong, and was approved by the Research Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The study began in mid-April 2011 and ended in mid-May 2011. Power analysis was conducted with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a 5% margin of error to estimate the required sample size. As no data on the prevalence of correct use of face masks could be found, the assumed prevalence was set at the recommended level of 50%. As a result, a total of 383 subjects were required. For inclusion in the survey, respondents had to be either an outpatient or a caregiver of an outpatient at the clinic. A systematic sampling approach was adopted to recruit outpatients and caregivers at the clinic by excluding every fourth outpatient/caregiver. As a result, 75% of the study subjects were invited to participate in the questionnaire survey.

The questionnaire was initially written in English and was translated into Chinese. Informed consent was obtained for every completed survey. A pilot questionnaire was pre-tested for 3 days at the same clinic. Informal interviews were conducted with the 76 respondents. These steps were taken to ensure the validity of the questions and proper comprehension. As a result, two questions were omitted from the final survey due to ambiguity, and the procedural question was amended by including pictures to aid understanding.

The final closed-ended questionnaire consisted of 33 items (Appendix 1, see online supplementary material). There were 5 items assessing knowledge, 19 items addressing attitudes and 6 items concerning practices. Another 3 items were used to collect data about demographics and medical history. The procedure for correct use of face masks was composed of a 3-part question addressing where the face mask covers, where the wire should be placed and which side should face the front. Knowledge items were adapted from guidelines recommended by the Centre for Health Protection10 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.11 Attitudes were rated on a five-point Likert scale and based on the Health Belief Model. The Likert scale was later collapsed into 3 categories for analysis. Questions concerning practices were based on the use of face masks in public places, at the clinic and at home, and whether the face mask was used for self-protection or to protect others.

Data were described using frequency and mean scores. Regarding knowledge, a score of 1 was given for each correct answer and 0 was given for each incorrect answer. Therefore, the range was 0–5. Attitude scores were calculated by giving −1 for negative attitudes, 0 for undecided and 1 for attitudes favoring face masks. The scores ranged from −19 to 19. Finally, practice scores were calculated by giving a score of 0 for those who did not wear a face mask, a score of 1 for those who sometimes wore a face mask, and a score of 2 for those who answered that they always wore a face mask. The maximum score was 12 and the minimum score was 0. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationship between knowledge, attitudes and practices. A P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate significance. Statistical analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Descriptions of sociodemographics

In total, 560 outpatients and caregivers were invited to participate in the survey. Of these, 399 completed the survey, the response rate was 71.3%, and 57.8% of the respondents were women. The mean age was 51.25 (range 18–81) years. Of those surveyed, 16.4% had a university or higher education (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants.

| Characteristics | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 158 (42.2) |

| Female | 216 (57.8) | |

| Total | 374 (100) | |

| Age group (years) | 18–29 | 29 (8.2) |

| 30–39 | 44 (12.4) | |

| 40–49 | 64 (18.1) | |

| 50–59 | 105 (29.7) | |

| ≥60 | 112 (31.6) | |

| Total | 354 (100) | |

| Education | Elementary or less | 71 (18.5) |

| High school | 249 (65.0) | |

| University or above | 63 (16.4) | |

| Total | 383 (100) | |

Knowledge of correct use of face masks

Only 52.0% (95% CI 47.1–56.9%) of respondents knew the correct procedure for wearing a face mask. Results revealed that 53.6% (95% CI 48.7–58.6%) of participants knew that covering one's mouth while coughing and sneezing was still necessary when wearing a face mask, and 71.4% (95% CI 66.9–75.9%) knew that a cloth face mask is not as effective as a surgical face mask. The majority of respondents (93.8%, 95% CI 91.4–96.2%) knew that a used face mask cannot be re-used, even if the wearer is not ill, and 84.8% (95% CI 81.2–88.4%) knew that a face mask does not help to protect the wearer against human immunodeficiency virus (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Summary of knowledge.

| Statement | % answered correctly (n) | % answered incorrectly (n) | % did not know (n) | %Total (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. When wearing a face mask at the clinic, there is no need to cover your mouth when sneezing or coughing | 53.6% (209) | 41.3% (161) | 5.1% (20) | 100% (390) |

| 2. A cloth face mask is as effective as a regular surgical face mask | 71.4% (277) | 15.2% (59) | 13.4% (52) | 100% (388) |

| 3. If I am not sick, the used face mask can be stored in a bag for later use | 93.8% (365) | 4.9% (19) | 1.3% (5) | 100% (389) |

| 4. A face mask helps to prevent human immunodeficiency virus | 84.8% (328) | 7.0% (27) | 8.3% (32) | 100% (387) |

| 5. Correct procedure | 52.0% (206) | 48.0% (193) | – | 100% (399) |

Attitudes toward use of face masks

Perceived susceptibility

As shown in Table 3 , 68% (95% CI 63.3–72.7%) of respondents believed that they were susceptible to getting ILI at the clinic. However, only 56.2% (95% CI 50.5–61.9%) believed that the chance of getting ILI was higher in a clinic than in a public place. Nearly three-quarters of the respondents (73.4%, 95% CI 69.0–77.8%) felt that ILI is still a concern despite the fact that the SARs and H1N1 crises are over.

Table 3.

Summary of attitudes and practices toward the use of face masks.

| Category | Statement | Agree (n) | Uncertain (n) | Disagree (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived susceptibility to ILI | I am more susceptible to ILI at the clinic than in public venues | 56.2% (163) | 9.3% (27) | 34.5% (100) |

| There is a high chance of having ILI transmitted to me while I am at the clinic | 55.2% (211) | 15.7% (60) | 29.1% (111) | |

| I feel that since the SARS and H1N1 crises are over, I no longer have to worry about contracting ILI | 15.1% (58) | 11.5% (44) | 73.4% (281) | |

| I feel that I am susceptible to getting ILI at the clinic | 68.0% (259) | 14.2% (54) | 17.8% (68) | |

| Perceived severity of ILI | I believe that getting ILI is serious | 85.1% (325) | 7.1% (27) | 7.9% (30) |

| Having ILI will be troublesome for me as I may spread it to loved ones | 91.9% (350) | 3.1% (12) | 5% (19) | |

| Having ILI will be troublesome for me as I have to take time off work | 59.6% (226) | 17.9% (68) | 22.4% (85) | |

| Perceived benefits of wearing a face mask | I believe that wearing a face mask is a good way to protect myself against ILI at the clinic | 88.5% (338) | 7.6% (29) | 3.9% (15) |

| At the clinic, wearing a face mask cannot prevent the transmission of ILI | 53.4% (156) | 12.3% (36) | 34.2% (100) | |

| Perceived barriers to wearing a face mask | I will only wear a face mask at the clinic if it is free | 8.1% (31) | 10.1% (39) | 81.8% (315) |

| Buying a face mask at the clinic is expensive | 38.1% (146) | 30.8% (118) | 31.1% (119) | |

| Wearing a face mask is troublesome because I cannot communicate properly | 19.2% (73) | 10.0% (38) | 70.9% (270) | |

| I would feel ashamed if I was the only person wearing a face mask at the clinic | 7.7% (28) | 8.0% (29) | 84.3% (306) | |

| It is easier to wear a face mask if everyone at the clinic is wearing one too | 50.1% (193) | 16.6% (64) | 33.2% (128) | |

| Cues to action | I would wear a face mask if there were more posters to remind me | 52.2% (200) | 17.5% (67) | 30.3% (116) |

| If the doctor tells me to, I will wear a face mask | 81.6% (240) | 8.5% (25) | 9.9% (29) | |

| If the nurse tells me to, I will wear a face mask | 85.0% (249) | 8.2% (24) | 6.8% (20) | |

| Self-efficacy | I know the proper steps for putting on a face mask | 88.4% (342) | 8.5% (33) | 3.1% (12) |

ILI, influenza-like illness; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

Perceived severity

Most respondents (85.1%, 95% CI 81.5–88.7%) believed that getting ILI is serious. The majority also agreed that having ILI would be troublesome as they believed that ILI can be transmitted to their loved ones (91.9%, 95% CI 89.2–94.7%) (Table 3).

Perceived benefits

Most respondents (88.5%, 95% CI 85.3–91.7%) believed that wearing a face mask is a good way to protect oneself against ILI. However, 53.4% (95% CI 47.7–59.1%) stated that wearing a face mask cannot fully prevent the transmission of ILI (Table 3).

Perceived barriers

Most respondents (81.8%, 95% CI 78.0–85.7%) disagreed with the statement ‘I would only wear a face mask at the clinic if it was free’. However, 38.1% (95% CI 33.24–42.96%) believed that buying a face mask at the clinic is expensive. In addition, 70.9% (95% CI 66.3–75.5%) responded that they disagreed that ‘Wearing a face mask is troublesome because I cannot communicate properly’, and 84.3% (95% CI 80.6–88.0%) would not feel ashamed if they were the only one wearing a face mask at the clinic. However, 50.1% of respondents (95% CI 45.1–55.1%) answered that if everyone else wore a face mask, it would be easier for them to wear it as well (Table 3).

Cues to action

Most respondents (85.0%. 95% CI 80.9–89.1%) indicated that they were more likely to wear a mask if a nurse reminded them, and 81.6% (95% CI 77.2–86.0%) responded that they would wear a mask if asked to do so by a doctor. Comparatively, posters were less likely to be a good cue to action, as only 52.2% (95% CI 47.2–57.2%) responded that it would increase their probability of wearing a mask (Table 3).

Self-efficacy

The study revealed that most respondents (88.4%, 95% CI 85.2–91.6%) believed that they knew the proper procedure for wearing a face mask (Table 3).

Practices related to use of face masks

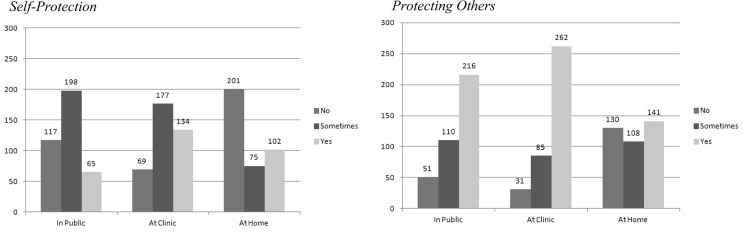

Practices were split into two categories: use of face masks to protect oneself against ILI and use of face masks to protect others against ILI (Fig. 1 ). Respondents were more likely to report wearing a face mask to protect others in public places (86.5%, 95% CI 83.1–89.9%) and at the clinic (91.8%, 95% CI 89.0–94.6%). Respondents reported lower use of face masks for self-protection in public places (69.2%, 95% CI 64.6–73.8%) than at the clinic (81.9%, 95% CI 78.0–85.8%). Use of face masks at home was lower than that in public places and at the clinic for protecting others (65.7%, 95%CI 60.9–70.5%) and self-protection (46.8%, 95% CI 41.8–51.8%).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of practices regarding the behaviors of self-protection and protection in public, at the clinic and at home.

Correlation between knowledge, attitudes and practices

The mean scores for knowledge, attitudes and practices were 3.51 [standard deviation (SD) 1.09], 8.76 (SD 4.21) and 6.84 (SD 3.27), respectively. There was low to moderate correlation between attitudes and practices (correlation coefficient 0.261, P < 0.001). No significant linear trend was found between knowledge and practices, or knowledge and attitudes (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Results of Pearson correlation coefficient analysis.

| Variables | Correlation coefficient | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge vs attitudes | 0.098 | 0.123 |

| Knowledge vs practices | 0.002 | 0.972 |

| Attitudes vs practicesa | 0.261 | 0.000 |

P < 0.001.

Discussion

Face masks have been recommended as a public health non-pharmaceutical intervention against ILI. However, in order for face masks to provide effective protection, the public must possess the correct knowledge for wearing them. In this study, 88.4% of respondents believed that they knew the correct steps for wearing a face mask; however, only 52.0% answered the procedural question correctly. These findings may be due to the fact that face masks have a relatively simple design, which leads many people to assume that they know the correct procedure for use. The low proportion of correct answers may reflect the lack of standard requirements for the packaging of face masks and their designs. In Hong Kong, there are no guidelines for facemask manufacturers to follow. The packaging of many face masks do not include clear instructions. This problem is compounded by the fact that designs for face masks differ between manufacturers. Some face masks have a colored side to indicate which side should face out. However, face masks that are white on both sides also exist. Without proper instructions and knowledge, it is difficult to wear a face mask correctly. In other knowledge items, respondents typically scored high. However, only 53.6% correctly answered ‘False’ to the statement ‘When wearing a face mask in the clinic, there is no need to cover your mouth when sneezing or coughing.’ This indicates that respondents did not know that face masks can only act as a barrier for large droplets and not for very small particle aerosols. This misconception could possibly lead to an increase in ILI transmission, as viruses can still be transmitted through the facemask cover. These findings indicate an urgent need for a better public health programme to increase knowledge about the correct wearing of face masks.

Attitudes toward the use of face masks were generally positive. Respondents rated nurses and doctors as being good sources for cues to action (85.0% and 81.6%, respectively). On the other hand, only 52.2% indicated that posters would serve as an effective reminder for wearing a face mask. This may be due to the fact that there are numerous posters in the waiting area for various health reminders. In fact, four posters related to the proper use of face masks were found within the clinic area. However, these posters mainly consisted of written instructions, which may be a problem for those who have difficulty reading. In addition, these posters were hidden amongst many other educational materials, which makes it difficult for them to be an effective cue to action.

In relation to the items addressing the practice of using face masks, the results indicate that respondents were most likely to wear face masks at the clinic. They were more likely to wear a face mask for protecting others rather than self-protection. The high prevalence rates of using face masks for self-protection and protecting others at the clinic (91.8% and 81.9%, respectively) highlight the importance of ensuring correct knowledge in wearing a face mask. This study found that respondents generally had a positive attitude toward the use of face masks, although correlation between attitudes and practices was not high (correlation coefficient 0.26, P < 0.05).

This study had some limitations. As the survey was self-administered, those who were illiterate may have been unwilling to participate. This may have resulted in a non-response bias. Steps were taken to minimize this bias by giving subjects the option of having an interviewer read the questions to them. In addition, the use of closed-ended questions may not have covered the whole range of answers. To overcome this limitation, a pilot survey and informal interviews were conducted prior to the start of the study. This was done to ensure that the survey was appropriate and covered the important items in relation to the use of face masks. Another limitation was that this study was only conducted in one clinic. Therefore, these results may not be generalized to all outpatient clinic populations. However, this study provides valuable insights for further investigation of the knowledge gap in the correct use of face masks. Future studies should include both private and public clinics, and explore factors related to the knowledge gap. By doing this, public health programmes can be better tailored to increase the level of knowledge about the use of face masks.

In conclusion, this study identified a knowledge gap about the correct use of face masks among outpatients and their caregivers. Attitudes and practices toward the use of face masks were generally positive, but correlation was not high. The results of this study indicate a knowledge gap that should be addressed by public health education. It is recommended that public health education campaigns should tailor efficient programmes to combat ILI transmission among outpatient clinic populations by improving knowledge about the correct use of face masks. Guidelines for facemask manufacturers should be created and enforced so that proper instructions are printed clearly on the packaging. Medical personnel also play an important role in increasing the use of face masks in the clinic setting. Future studies are needed to investigate whether this knowledge gap exists in other outpatient clinics in Hong Kong.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the staff and all the study participants at the Family Medicine Training Centre, Prince of Wales Hospital. In particular, the author would like to thank Professor Linwei Tian, Professor Jean Kim, Professor Joseph Lau, Professor William Goggins, Mr Alvin Wong, Ms Hale Ho, Ms Iris Chan and Mrs Sanny Sung.

Ethical approval

Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Funding

None declared.

Competing interests

None declared.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2012.09.010.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2005. Avian influenza: assessing the pandemic threat.http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2005/WHO_CDS_2005.29.pdf Available at: [last accessed 11.01.11] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health and Human Services . 2005. HHS pandemic influenza plan.http://www.flu.gov/planning-preparedness/federal/hhspandemicinfluenzaplan.pdf Available at: [last accessed 15.01.11] [Google Scholar]

- 3.General Secretariat for National Defence . 2007. National plan for the prevention and control of influenza pandemic.http://www.sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/planpandemiegrippale_anglais.pdf Available at: [last accessed 02.02.11] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jefferson T., Del Mar C., Dooley L., Ferroni E., Al-Ansary L.A., Bawazeer G.A. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses: systematic review. BMJ. 2009;339:b3675. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aiello A.E., Murray G.F., Perez V., Coulborn R.M., Davis B.M., Uddin M. Mask use, hand hygiene, and seasonal influenza-like illness among young adults: a randomized intervention trial. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:491–498. doi: 10.1086/650396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . 2009. Advice on the use of masks in the community setting in influenza A (H1N1) outbreaks.http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/Adviceusemaskscommunityrevised.pdf Available at: [last accessed 13.01.11] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau J.T., Griffiths S., Choi K.C., Lin C. Prevalence of preventive behaviours and associated factors during early phases of the H1N1 influenza epidemic. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38:374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau J.T., Kim J.H., Tsui H.Y., Griffiths S. Anticipated and current preventive behaviors in response to an anticipated human-to-human H5N1 epidemic in the Hong Kong Chinese general population. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beggs C.B., Shepherd S.J., Kerr K.G. Potential for airborne transmission of infection in the waiting areas of healthcare premises: stochastic analysis using a Monte Carlo model. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:247. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centre for Health Protection . 2008. Use mask properly [Internet]http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/Use_Mask_Properly.pdf [cited 2011 Jan11]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2004. Guidance for the selection and use of personal protective equipment in healthcare settings [Powerpoint]http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/ppe/PPEslides6-29-04.pdf [cited 2011 Jan 10]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.