Graphical abstract

Keywords: Peptide aldehyde, Acetal, Thioacetal, Cysteine protease inhibitor

Abstract

We have investigated practical synthetic routes for the preparation of peptide aldehyde on a solid support. Peptide aldehyde was synthesized via efficient transformation of acetal/thioacetal structures.

Peptide with C-terminal aldehyde is of interest due to its property as a transition-state analogue toward numerous classes of proteolytic enzymes; aspartyl1, 2 and cysteine protease3, 4 are inhibited by peptide aldehyde. Since leupeptin5 is produced by actinomycetes, which inhibit a variety of proteases potently, natural peptide aldehydes6 are attractive targets for drug discovery. Peptide aldehyde can also be used as a key intermediate in the syntheses of pseudo-peptides, particularly in the synthesis of reduced peptide by reduced fragment condensation. Several methods for solid phase synthesis of peptide aldehyde have been reported: reduction of Weinreb amide,7, 8 oxidation of alcohol,9 or ozonolysis10, 11 of the corresponding olefin. However Weinreb amides and ozonolysis are limited to peptide aldehydes without reductant or oxidant labile amino acid sequences. On the other hand, acetal linker,12, 13 oxazoline linker,14, 15 threonine-type linker,16 and semicarbazone linker17 were developed for the attachment of aldehydes. Cleavage of the peptide aldehydes from these linkers required strong acidic conditions, HF, TFA, or AcOH, and so forth, which frequently caused serious problems. In the course of our research regarding cysteine protease inhibitors,18 we prepared several peptide aldehydes via a thioacetal structure on a solid support since the aldehyde group seems to be effective for the thiol functional group of cysteine protease.19 At that time, we found that the conversion of an acetal to an aldehyde was quite slow but that the thioacetal can be efficiently converted into the desired aldehyde by treatment with N-bromo succinimide (NBS). In this case, the Fmoc-His(Trt)-H and decane-1,2,10-triol linker12 were selected and peptide aldehydes with a histidine residue at the P1 position were prepared using solid phase synthesis. Subsequently, we discovered a tetrapeptide with C-terminal aldehyde with potent inhibitory activity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3C-like protease.20 Herein, we report a practical synthetic route for the preparation of several peptide aldehydes with different amino acids and commercially available linkers on a solid support.

Our synthetic plan centers on the transformation of acetal to aldehyde via a thioacetal structure. Although the acetal linker using decane-1,2,10-triol reported by Yao and Xu12 is stable and useful for solid phase peptide synthesis, decane-1,2,10-triol is not commercially available and the acetal is stable in TFA. When the resin was treated with 95% TFA/H2O, the desired peptide aldehyde was obtained in poor yield.12 We thought that the peptide acetal (B), which was converted from the amino acetal (A) containing commercially available alkyl triols by solid phase peptide synthesis, transformed peptide thioacetal (C) by treatment with EtSH in the presence of catalytic Lewis acid. As a final step, the thioacetal (C) thus obtained could be treated with NBS in 10% CH2Cl2 aq to give the desired peptide aldehyde (D). In addition, N-terminal protection was necessary to avoid the (hemi-) aminal formation between N-terminal amine and C-terminal aldehyde otherwise complexed mixtures were given (Scheme 1 ).

Scheme 1.

Synthetic plan for peptide aldehyde via thioacetal.

To investigate the effect of the linker length, transformation of acetal with two alkyl triols and BF3–Et2O complex as an acidic catalyst was commenced in the present study.

According to the condition in the previous literature20 (entry 1), the acetalization of Fmoc-Ala-H (1) with 1.5 equiv of hexane-1,2,6-triol and 10 mol % BF3–Et2O in CH2Cl2 at room temperature for 3 h obtained the desired hydroxyl acetal (2b) in 34% yield (entry 2). After attempting several conditions, we optimized the condition with 1.0 equiv of hexane-1,2,6-triol and 5 mol % BF3–Et2O in CH2Cl2 for 5 h to give 2b in 73% yield (entry 5). While the reaction mixture using CH2Cl2 to give 2c was a suspension because of the insolubility of trimethylolethane (entry 6), THF was effective to enable the acetalization of 1 in 86% yield (entry 7) (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

| Entry | Triol linker (equiv) | Solvent | BF3–Et2O (mol %) | Time (h) | Alcohol (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Decane-1,2,10-triol (1.5) | CH2Cl2 | 10 | 3 | 2a (60) |

| 2 | Hexane-1,2,6-triol (1.5) | CH2Cl2 | 10 | 3 | 2b (34) |

| 3 | Hexane-1,2,6-triol (1.5) | THF | 10 | 25 | 2b (38) |

| 4 | Hexane-1,2,6-triol (1.0) | CH2Cl2 | 100 | 2 | 2b (60) |

| 5 | Hexane-1,2,6-triol (1.0) | CH2Cl2 | 5 | 5 | 2b (73) |

| 6 | Trimethylolethane (1.0) | CH2Cl2 | 100 | 6 | 2c (61) |

| 7 | Trimethylolethane (2.0) | THF | 5 | 18 | 2c (86) |

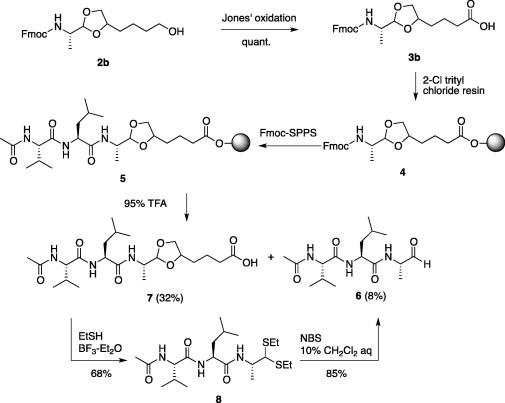

After the oxidation of 2b by Jones’ condition, carboxylic acid (3b) with DIPEA in DMF was loaded on 2-chloro trityl chloride resin to give 4. After the conventional Fmoc-solid phase peptide synthesis of 4 using diisopropylcarbodiimide/1-hydroxybenzotriazole coupling and Fmoc deprotection by 20% piperidine/DMF, the treatment of resin (5) with 95% TFA gave the desired peptide aldehyde, Ac-Val-Leu-Ala-H (6) and acetal carboxylic acid (7) in 8% and 32% yields, respectively. We found that the acetal carboxylic acid (7) was smoothly converted to thioacetal (8) in 68% yield by treatment with 10 equiv of EtSH and catalytic BF3–Et2O for several minutes at room temperature. Subsequently, peptide aldehyde (6) was quickly obtained from thioacetal (8) by NBS in 10% CH2Cl2 aq in 85% yield. These results suggested that the cheap hexane-1,2,6-triol linker compared favorably with Yao’s octane-1,2,10-triol linker and, furthermore, it was possible to convert acetal to thioacetal quickly. On the other hand, acetal (3c) oxidized from 2c was attempted to give 6 using the above protocol, which had similar results, giving the corresponding peptide aldehyde (6) in poor yield. TFA-mediated cleavage process from the resin with 3c afforded the trace amount of 6 with the corresponding acetal carboxylic acid (∼10%). Although each reaction via thiacetal (8) for the desired 6 proceeded to give the corresponding compounds, conversion of acetal to thioacetal with EtSH and catalytic BF3–Et2O was extremely slow because of the steric hindrance of acetal composed of trimethylolethane. For this reason, we selected the hexane-1,2,6-triol linker for the synthesis of other sequences (Scheme 2 ).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of peptide aldehyde by direct acetal/thioacetal/aldehyde transformation.

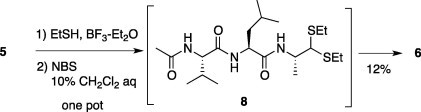

Although treatment of resin (5) with EtSH and catalytic BF3–Et2O followed by the addition of NBS as a one-pot reaction afforded Ac-Val-Leu-Ala-H (6) in 12% overall yield, the yields markedly depended on the nature of the sequence, especially C-terminal amino acid. The one-pot reaction using His, Arg, and β-(2-Thienyl)Ala at the C-terminal position was unsuccessful in detecting the desired products. We found that stepwise conversion was effective to obtain the designed peptide aldehyde using isolated thioacetal (Scheme 3 ).

Scheme 3.

One-pot synthesis of peptide aldehyde (6).

This stepwise method was tested by synthesizing selected peptide aldehydes (15)–(20). The yields of thioacetals (10)–(14) were the overall yield from loading on resin, and conversion of acetal to thioacetal proceeded smoothly with simultaneous deprotection of side chains of the corresponding amino acid residues. Isolation yield of Ac-Thr-Val-Phe(Hexahydro)-His-(OEt)2 (9) prepared using Yao’s linker was 31% overall yield (entry 1).20 Peptide thioacetals (10)–(14) were synthesized in moderate yield (entries 2–6). As a final step, thioacetals were treated with NBS in 10% CH2Cl2 aq to afford the desired peptide aldehydes within a few minutes and immediately the products caused some epimerization of the α-bearing the aldehyde and then decomposed. Therefore, it was important to quench the reaction mixture quickly to purify it by silica gel column chromatography or RP-HPLC. In order to check chiral integrity, the peptide aldehydes were analyzed by 1H NMR and the aldehyde appearing at the neighboring δ 9.6 ppm was assessed. In addition, we attempted the synthesis of tokaramide A (20) using this methodology. Although aldehyde formation from thioacetal (14) was moderate, it afforded tokaramide A (20) as a cyclic structure (entry 6) (Table 2 ).18

Table 2.

Sequences of synthetic peptide aldehydes and their chemical yields.

| Entry | Thioactal (%) | Aldehyde (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ac-Thr-Val-Phe(Hexahydro)-His-(SEt)2 (9) | (31) | Ac-Thr-Val-Phe(Hexahydro)-His-H (15) | (40) |

| 2 | Ac-Phe-Leu-Ala-(SEt)2 (10) | (4) | Ac-Phe-Leu-Ala-H (16) | (21) |

| 3 | Ac-Ala-Val-Leu-Leu-(SEt)2 (11) | (7) | Ac-Ala-Val-Leu-Leu-H (17) | (48) |

| 4 | Ac-Leu-Ala-Phe-(SEt)2 (12) | (27) | Ac-Leu-Ala-Phe-H (18) | (44) |

| 5 | Ac-Leu-Phe-Ser-(SEt)2 (13) | (12) | Ac-Leu-Phe-Ser-H (19) | (57) |

| 6 | p-HBz-Val-Val-Arg-(SEt)2 (14) | (12) | p-HBz-Val-Val-H (20) | (23) |

In conclusion, a very simple and cheap alkyl triol linker for attaching Fmoc-aminals to solid phase peptide synthesis was developed. Peptide acetals were efficiently converted to thioacetal structures followed by treatment of NBS to give peptide C-terminal aldehydes. Although it is difficult to apply this procedure to Trp/Cys-containing peptides, general scope and limitations using several amino acids are now underway.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 21689004 to H.K. from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References and notes

- 1.Hamada Y., Kiso Y. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2012;7:903–922. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2012.712513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kakizawa T., Sanjoh A., Kobayashi A., Hattori Y., Teruya K., Akaji K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:2785–2789. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenthal P.J. Int. J. Parasitol. 2004;34:1489–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato D., Boatright K.M., Berger A.B., Nazif T., Blum G., Ryan C., Chegade K.A.H., Salvesen G.S., Bogyo M. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005;1:33–38. doi: 10.1038/nchembio707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aoyagi T., Takeuchi T., Matsuzaki A., Kawamura K., Kondo S., Hamada M., Maeda K., Umezawa H. J. Antibiot. 1969;22:283–286. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.22.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fusetani N., Fujita M., Nakao Y., Matsunaga S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:3397–3402. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00618-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferentz J.-A., Paris M., Heitz A., Velek J., Liu C.-F., Winternitz F., Martinez J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:7871–7874. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferentz J.-A., Paris M., Heitz A., Velek J., Winternitz F., Martinez J. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:6792–6796. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pothion C., Paris M., Heitz A., Rocheblave L., Rouch F., Fehrentz J.-A., Martinez J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:7749–7752. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paris M., Heitz A., Guerlavais V., Christau M., Fehrenta J.A., Martinez J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:7287–7290. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall B.J., Sutherland J.D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:6593–6596. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao W., Xu H.Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:2549–2552. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kappel J.C., Barany G.J. J. Pept. Sci. 2005;11:525–535. doi: 10.1002/psc.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka M., Oishi S., Ohno H., Fujii N. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2007;13:271–279. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ede N.J., Bray A.M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:7119–7122. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang W., Wang W., Zhi X.-X., Zhang B., Wei P., Xu H.-Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:1187–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.11.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy A.M., Dagnino R., Vallar P.L., Trippe A.J., Sherman S.L., Lumpkin R.H., Tamura S.Y., Webb T.R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:3156–3157. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konno H., Nosaka K., Akaji K. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:9067–9071. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akaji K., Konno H., Onozuka M., Makino A., Saito H., Nosaka K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:9400–9408. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akaji K., Konno H., Mitsui H., Teruya K., Hattori Y., Ozaki T., Kusunoki M., Sanjho A. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:7962–7973. doi: 10.1021/jm200870n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]