Abstract

Cyclodepsipeptides of the enniation-, PF1022-, and verticilide-family represent a diverse class of highly interesting natural products with respect to their manifold biological activities. However, until now no stepwise solid-phase synthesis has been accomplished due to the difficult combination of N-methyl amino acids and hydroxycarboxylic acids. We report here the first stepwise solid-phase synthesis of the anthelmintic cyclooctadepsipeptide PF1022A based on an Fmoc/THP-ether protecting group strategy on Wang-resin. The standard conditions of our synthesis allow an unproblematic adaption to an automated peptide synthesizer.

Abbreviations: ACN, acetonitrile; Boc, tert-butyloxycarbonyl; BOPCl, N,N′-bis(2-oxo-3-oxazolidinyl)phosphinic chloride; DCM, dichloromethane; DEAD, diethylazodicarboxylate; DHP, 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyrane; DIC, N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide; DIEA, diisopropylethylamine; DMAP, 4-dimethylaminopyridine; DMF, dimethylformamide; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; EDCI, 1-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide methiodide; Fmoc, 9-Fluorenyl-methoxycarbonyl; HATU, N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-O-(7-azabenzo-triazol-1-yl)uroniumhexa-fluorophosphate; HOAt, 1-hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole; HOBt, 1-hydroxy-benzotriazole; MeOH, methanol; TEA, triethylamine; TFA, trifluoro acetic acid; THF, tetrahydrofuran; THP, tetrahydropyranyl; TPP, triphenylphosphane; p-TsOH, para-toluenesulfonic acid

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Depsipeptides are defined as heterodetic peptides with at least one ester bond. While most depsipeptides contain only few, usually irregular ester groups, depsipeptides with alternating ester bonds are less common. Examples (Fig. 1 ) of these highly symmetric natural products comprise PF1022A (1), verticilide (3), bassianolide (4), valinomycin (5), and the enniatins (6–9).1 These regular cyclodepsipeptides share several characteristic structural features, among those the occurrence of (R)-hydroxycarboxylic acids and N-methyl amino acids.

Fig. 1.

Naturally occurring cyclodepsipeptides.

Natural depsipeptides, in particular cyclodepsipeptides, are of increasing interest for pharmaceutical research because of their wide range of biological activities (Fig. 1).2 For instance, valinomycin (5) a well known potassium-selective ionophore was recently reported to be the most potent agent against severe acute respiratory-syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV).3 Verticilide (3), a cyclooctadepsipeptide isolated from a Verticilium sp. shows a strong and selective inhibiting activity on ryanodine binding in insects.4 Bassianolide (4), another cyclooctadepsipeptide, and the enniatins (6–9), a large family of cyclohexadepsipeptides, display diverse biological activities, including antibiotic, antifungal, insecticidal, antiproliferative, and cell migration inhibitory activities.5 The 24-membered cyclooctadepsipeptide PF1022A (1), a metabolite of Mycelia sterilia (Rosselinia sp.), originally isolated from leaves of Camellia japonica has been established as a resistance-breaking anthelmintic with low toxicity in animals (Fig. 1).6, 7 Other cyclodepsipeptides act by selective ion transport through cellular membranes.

Despite the high potential of cyclodepsipeptides for drug discovery, only very limited screening and structure–activity data have been reported until now, probably due to the difficult access to these compounds. The combination of amino acids and bulky hydroxycarboxylic acids represents a formidable challenge for a solid-phase synthesis, which is on the other hand a prerequisite for the preparation of larger compound collections needed for biological screening. The stepwise assembly of such compounds is expected to be particularly difficult when N-methyl amino acids are involved.8 Due to the increased steric hindrance couplings need more time with the consequence that dioxomorpholine formation and epimerization can become the predominant side-reactions.9, 10, 11 The difficulties, resulting from the stepwise assemblage of N-methyl amino acids have been impressively demonstrated in several cyclosporine syntheses.12, 13

Although advanced reagents, such as BMTB and DFET have been developed and applied for the coupling of sterically hindered N-methyl amino acids, high-yielding ester bond assemblage on solid support remains a synthetic problem.14, 15 Besides standard reagents, such as DIC/DMAP alsotriphosgene and hexafluoroacetonides of α-hydroxycarboxylic acids have been employed for the construction of depsipeptides.16, 17, 18

Usually, the ester bonds are either assembled beforehand in solution and only the peptide bonds are formed on the resin or the hydroxycarboxylic acids are introduced without any protection.19, 20 Only a few procedures have been published for stepwise solid-phase depsipeptide syntheses, the most impressive one comprises a twenty-four step total synthesis of the cyclododecadepsipeptide valinomycine (5), including the on-resin formation of six ester bonds.21, 22, 23 However, no stepwise solid-phase syntheses of depsipeptides containing N-methyl amino acids have been accomplished until now. In this paper we wish to report a solid-phase total synthesis of the cyclooctadepsipeptide PF1022A in which all ester- and amide-bonds are formed on the support.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Protecting group strategy and preparation of building blocks

In principle, the most frequently used Fmoc- and Boc-protecting group strategies should be applicable also for the solid-phase synthesis of depsipeptides. However, both of them have their own problems when ester bonds are involved. The basic conditions needed for the removal of the Fmoc-group may cause a partial ester cleavage, diketopiperazine formation and enhanced racemization of the chiral hydroxy acids. On the other hand, Fmoc-protecting schemes are well established for standard supports, such as the Wang-resin and can be easily adapted on a peptide synthesizer. Diketopiperazine formation is drastically reduced or even suppressed under the strong acidic cleavage conditions used for the cleavage of Boc protecting groups. However, activated ester bonds as those from PhLac for instance, may be affected, too. Additionally, the resins compatible with Boc-protecting, mainly the Kaiser-oxime and the PAM-resin are significantly more expensive and have lower loadings compared to Wang-resin.

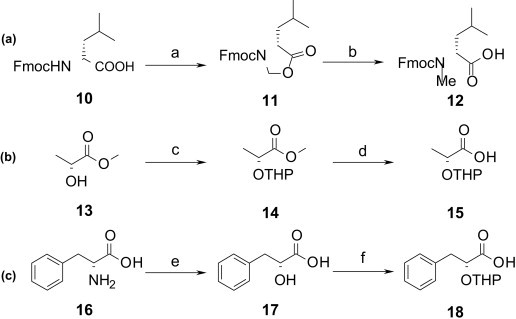

Silyl ethers and acetyl groups have been employed in solid-phase syntheses as protecting groups for the OH-function of hydroxy acids.24 While acetyl groups are cleaved under strong basic conditions, bearing again the risk of racemization, silyl ethers appear generally unsuited for the coupling of N-methyl amino acids and hydroxy acids due to the sterical shielding of the bulky silyl residue. For these reasons we chose the THP-protecting group, which is cleaved under mild acidic conditions, compatible even with the Boc-protecting group.25 Fmoc protected N-methyl leucine and THP protected hydroxy acids were prepared according to standard literature procedures (Scheme 1 ).26, 27, 28, 29, 30

Scheme 1.

Preparation of Fmoc-NMe-leucine (a), THP-Lac (b) and THP-PhLac (c). Reagents and conditions: (a) paraformaldehyde, p-TsOH, toluene, 112 °C, 24 h, 100%; (b) AlCl3, Et3SiH, DCM, rt, 1 h, 63%; (c) DHP, p-TsOH, toluene, 50 °C, 3 h, 93%; (d) 1 M THF/LiOH (5:3, aq), 0 °C, 5 h, 85%; (e) 40% NaNO2 (aq), H2SO4, 2 h 0 °C, 16 h rt, then add 40% NaNO2 in H2SO4, 6 h 0 °C, then 16 h rt, 62%; (f) DHP, p-TsOH, pyridine, DCM, rt, 16 h, 100%.

2.2. Solid-phase synthesis of PF1022A

First we used the Kaiser-oxime resin, which we had already applied successfully in the course of a didepsipeptide segment synthesis of PF1022A (1) and emodepside (2). However, in the considerably longer stepwise synthesis of PF1022A, deletion- and failure-sequences accumulated, accompanied by premature cleavages from the resin, which resulted in an inseparable mixture of products after six or seven couplings.

In a second attempt we chose the Wang-resin, being well aware of the potential problems arising from the basic cleavage conditions of the Fmoc-group. Since the strongly solvating DMF has been shown to be an unfavorable solvent in critical couplings with respect to yield, diketopiperazine formation and degree of racemization we used the less solvating THF, in which all reagents were soluble and the Wang-resin still showed good swelling properties.14, 31 After each coupling step a small portion of the resin was cleaved and the product analyzed by HPLC-MS. The results of our optimization experiments are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

PF1022A solid phase-synthesis—optimization of coupling-steps 1–4

| Step (entry) | Building block (3.0 equiv) | Product (bond formed) | No. of couplings | Conditions (equiv) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | THP-PhLac | 19 (ester) | 3 | DIC (3.0), DMAP (0.1) | 62a |

| 1b | 2 | DIC (3.0), DMAP (3.0), HOBt (3.0) | 92a | ||

| 1c | 2 | EDCI (3.0), DMAP (0.1) | 17a | ||

| 1d | 3 | HATU (2.0), DIEA (3.0) | 36a | ||

| 2a | Fmoc-NMe-Leu | 20 (ester) | 3 | DIC (3.0), DMAP (0.1) | 91b |

| 2b | 2 | DIC (3.0), DMAP (3.0), HOBt (3.0) | 93b | ||

| 2c | 2 | EDCI (3.0), DMAP (0.1) | 44b | ||

| 3a | THP-Lac | 21 (amide) | 2 | HATU (2.0), DIEA (3.0) | 77a |

| 3b | 2 | DIC (3.0), DMAP (0.1) | 54a | ||

| 3c | 2 | DIC (3.0), DMAP (3.0), HOBt (3.0) | 48a | ||

| 3d | 2 | EDCI (3.0), DMAP (0.1) | 19a | ||

| 3e | 1 | 15 acid chloride (3.0), DMAP (1.0) | 34a | ||

| 4a | Fmoc-NMe-Leu | 22 (ester) | 2 | DIC (3.0), DMAP (0.1) | 51b |

| 4b | 2 | DIC (3.0), DMAP (3.0), HOBt (3.0) | 77b | ||

| 4c | 1 | Acid chloride (3.0), DMAP (1.0) | 5b | ||

| 4d | 1 | (Fmoc-NMe-Leu)2O (3.0 equiv), DMAP (3.0 equiv) | 38b | ||

| 4e | 2 | TPP (3.0 equiv), DEAD (3.0 equiv) | 51b |

Gravimetric determination of the product after deprotection and cleavage from the resin.

UV-determination after Fmoc removal. Yields calculated on a loading of 1.07 mmol/g resin. THF was used as solvent in all experiments.

As expected, the coupling-yields were strongly dependent on the residue used as the first building block, on the coupling reagents and conditions. THP-PhLac 18, which was used as the anchoring-residue due to its lower tendency to form dioxomorpholines compared to THP-Lac 15, could be coupled to the resin in over 90% yield with the reagent mixture DIC/DMAP/HOBt (entry 1b, Table 1) in two coupling cycles. Without HOBt the reactivity of the reagent system was distinctly reduced and even after three couplings the yield was only 62%. Remarkably, EDCI failed completely and even HATU, which has been used quite frequently as reagent for ester formation gave only a moderate coupling yield in the anchoring step.32, 33 In the first chain-extension reaction an ester bond between the anchored PhLac and Fmoc-NMe-Leu had to be established. Best yields (93%) were obtained again with DIC/DMAP/HOBt after two coupling cycles.

The next step, removal of the Fmoc-group from the didepsipeptide segment 20, is in particular prone to the formation of dioxomorpholines. Extensive studies in the literature demonstrate the critical role of the first and second amino acid as well as the coupling conditions. Sterically demanding amino acids (Val, Leu, Phe) in the first position and N-methyl amino acids in the second position, which exactly complies with the PF1022A situation, generally facilitate piperazinedione formation.34, 35, 36 Even after careful optimizations, we were not able to reduce the dioxomorpholine formation for this step to a content lower than 10–15% in the cleavage solution. Noteworthy, in all following Fmoc-group removals dixomorpholine formation was found between only 1% and 5% at maximum.

Several methods were tested for the coupling of THP-Lac 15 to resin-bound NMe-Leu (20→21), including THP-Lac acid chloride (entry 3e, Table 1 and Scheme 2). While this method gave only low yields largely due to insufficient coupling, epimerization, and resin-cleavages, good results for the amide bond formation were obtained with HATU and the DIC/DMAP/HOBt reagent. Since the carbodiimides are known for their risk of racemization, HATU was used for all subsequent amide forming couplings.

Scheme 2.

Solid-phase synthesis of PF1022A. Reagents and conditions: (a) DIC, HOBt, DMAP, THF, rt, 16 h; (b) p-TsOH, DCM/MeOH 97:3, rt, 2×1 h; (c) Fmoc-NMe-Leu 12, DIC, HOBt, DMAP, THF, rt, 16 h; (d) 25% piperidine/THF, rt, 30 min; (e) THP-Lac 15, HATU, DIEA, THF, rt, 16 h; (f) THP-PhLac 18, HATU, DIEA, THF, rt, 16 h; (g) 50% TFA/DCM, rt, 1.5 h; (h) BOPCl, DIEA, DCM, rt, 48 h.

The reaction between resin-bound Lac and NMeLeu (21→22) turned out to be more difficult than the previous ester formations between the Wang-resin and PhLac (18→19) on the one side and PhLac/NMeLeu (19→20) on the other side (Scheme 2 ). Thus, in addition to DIC, further procedures frequently used for the formation of difficult ester bonds, such as the highly reactive Fmoc-NMe-Leu acid chloride, the Yamaguchi dichlorobenzoate active ester (entry 4d, Table 1) and the Mitsunobo (entry 4e, Table 1) coupling with (S)-lactic acid were studied.37, 38 Both the amino acid chloride and the Yamaguchi method afforded insufficient yields while the Mitsunobo reaction gave somewhat higher yields. However, the DIC/DMAP/HOBt reagent system remained superior also for this coupling step.

Standard conditions were used for the removal of the Fmoc-protecting group (THF, 25% piperidine, 30 min). The THP-protecting groups were removed quantitatively with diluted p-TsOH (5 mg/mL in DCM/MeOH 97:3, 2×1 h) according to the procedure published by Kuisle.23 Due to the symmetry of PF1022A the remaining four chain-elongation reactions are simple repeats of the first couplings. Thus, no more optimizations were conducted. The yield of the linear octadepsipeptide 25 after removal of the N-terminal Fmoc-group and cleavage from the resin (50% TFA in DCM, 1.5 h, quantitative) was 16%, which corresponds to an average yield of 89% for each of the sixteen steps on solid support (Scheme 2).

The macrocyclization reaction, performed under high-dilution conditions in DCM with BOPCl as coupling reagent, afforded PF1022A in almost quantitative yield, regardless of whether the purified or the crude precursor 25 was employed. We found it very convenient to work with the crude octadepsipeptide because this avoided a costly and time-consuming preparative HPLC purification. Furthermore, PF1022A can be easily separated from non-cyclized by-products by flash-chromatography with silica gel due to its considerably higher lipophilicity. The unusual high macrocyclization yield can be attributed to a cis-amide bond between a leucine and lactic acid, which brings the N- and C-terminus in close proximity and thus facilitates the cylization reaction.39 PF1022A (1) obtained by synthesis was completely identical with respect to biological and spectroscopical data with a natural reference sample.

3. Summary and conclusion

We have developed a methodology for the stepwise coupling of N-methyl amino acids and hydroxycarboxylic acids on solid support, which allows the preparation of the anthelmintic cyclooctadepsipeptide PF1022A (1) in an overall yield in a range of 13–16% (89% average yield for each step). The synthesis comprises seventeen steps, sixteen of which are performed on solid support followed by a solution macrocyclization. Albeit there is still room for improvements in particular in the amide-bond forming steps, our standard conditions allow an easy adaption to an automated synthesizer as a prerequisite for the preparation of cyclodepsipeptide screening-libraries.

4. Experimental

4.1. General

The starting material (d)-phenyllactic acid, and was either purchased or prepared by standard literature procedures.28 All reactions except the saponification were performed in dried solvents. Dichloromethane and the reagents DIEA and piperidine were refluxed for 1 h over calcium hydride and distilled. THF was refluxed for several hours over LiAlH4 and then distilled and toluene was dried by filtration through basic alumina. The instrumentation used was as follows: 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C on a Bruker Avance 400 (400.13 MHz for 1H NMR, 100.62 MHz for 13C NMR) or Bruker Avance III 600 (600.13 MHz for 1H NMR, 150.90 MHz for 13C NMR). IR-spectra were measured on a Nicolet PROTÉGÉ 460 Spectrometer E.S.P. HPLC-MS was performed on a Varian 500 Ion-Trap LC-ESI-MS system or on a Bruker MicroTOF (column: 5 μm RP18) with ACN/H2O gradient 10/90 to 95/5. High-resolution MS were measured on a Bruker MicroTOF. Preparative low pressure chromatography (LPLC) was performed using silica gel 60 μm (230–400 mesh, Macherey–Nagel), Büchi pump. TLC: Silica gel 60 F254 (Merck). Melting points (mp) were determined with a Buechi 535 melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. The progress of the solid phase reactions was detected either by the bromophenolblue color test, determination of resin loading by UV determination of the Fmoc-group cleavage product or by test cleavages and HPLC-MS analysis.40

4.2. Synthesis of the building blocks in solution

4.2.1. (S)-4-Isobutyl-5-oxo-oxazolidine-3-carboxylic acid 9H-fluoren-9-yl methyl ester (11)

A mixture containing paraformaldehyde (45.28 g, 1.49 mol), Fmoc-(l)-leucine (80.00 g, 0.22 mol), and p-TsOH (4.52 g, 23.53 mmol) was refluxed in toluene (400 mL) for 24 h in a dean stark apparatus until water separation was complete. The reaction was cooled to room temperature, washed with saturated NaHCO3 solution, dried with Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo to yield oxazolidine 11 (81.89 g, 0.22 mol, 100%) as a white solid, which was used without further purification. Mp 68–70 °C; IR (KBr): 1721, 1799 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=0.84 (m, 6H, CδH3-Leu), 1.33–1.87 (m, 3H, CβH2-Leu, CγH-Leu), 4.25 (m, 2H, CH2–Fmoc), 4.70 (m, 2H, CH–Fmoc, CαH-Leu), 5.08 (m, 2H, CH2–oxazolidinone), 7.21–7.79 (m, 8H, Ar–H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=6.4, 21.0, 23.1, 24.7, 37.2, 47.2, 56.4, 67.6, 120.0, 124.7, 124.8, 125.0, 125.1, 127.1, 127.1, 127.7, 141.4, 143.8, 143.9, 156.5, 157.1, 177.6 ppm; MS (ESI): m/z=144 (7), 179 (100), 366 ([M+H]+, 21), 388 (26); HRMS (ESI): M++Na, found 388.1519; C22H23NNaO4 requires 388.1519; Anal. Calcd for C22H23NO4: C, 72.31; H, 6.34; N, 3.83; found: C, 72.36; H, 6.47; N, 3.86.

4.2.2. (S)-2-[(9H-Fluoren-9-yl-methoxycarbonyl)-methyl-amino]-4-methyl-pentanoic acid (12)

Triethylsilane (36.61 g, 0.31 mol) was added to a suspension of compound 11 (56.94 g, 0.156 mol) and AlCl3 (41.98 g, 0.31 mol) in DCM (1000 mL). After stirring for 60 min at room temperature the mixture was washed with 1 M HCl (3×, 400 mL each), dried with Na2SO4, concentrated in vacuo, and crystallized (cyclohexane/DCM 8:2) to provide N-Fmoc-N-methyl leucine 12 (35.94 g, 0.098 mol, 63%) as a white crystalline solid. Mp 112–114 °C (lit.30 113–116 °C); −19.5 (c 1.0, DMF); IR (KBr): 1655, 1754, 3427 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=0.94–1.03 (m, 6H, CH3-Leu), 1.47–1.79 (m, 3H, CβH2-Leu, CγH-Leu), 2.91 (s, 3H, NCH3), 4.24 (m, 1H, CH–Fmoc), 4.46 (m, 2H, CH2–Fmoc), 4.62 and 4.98 (2m, 1H, CαH-Leu), 7.28–7.44 (m, 4H, Ar–H), 7.57 (m, 2H, Ar–H), 7.79 (m, 2H, Ar–H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=6.8, 21.1, 37.2, 24.6, 30.2, 47.2, 56.3, 67.6, 119.9, 124.7, 124.8, 125.0, 125.1, 127.1, 127.1, 127.6, 141.3, 143.8, 143.9, 156.4, 157.1, 177.1 ppm; MS (ESI): m/z=146 (7), 179 (7), 368 ([M+H]+, 100), 385 (16); HRMS (ESI): M++Na, found 390.1681; C22H25NNaO4 requires 390.1676; Anal. Calcd for C22H25NO4: C, 71.91; H, 6.86; N, 3.81; found: C, 71.61; H, 6.96; N, 3.82.

4.2.3. (2R)-2-(Tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)-propanoic acid methyl ester (14)

Dihydropyran (8.98 g, 105.66 mmol) was dropped within 1 h at 50 °C to a solution of methyl (d)-lactate (10.00 g, 96.06 mmol) and p-TsOH (165.41 mg, 0.96 mmol) in toluene (100 mL). After stirring for 2 h at this temperature the solution was washed with saturated NaHCO3 solution, dried with Na2SO4, filtrated, and evaporated. Kugelrohr distillation (8.9×10−2 mbar, 70 °C) provided THP–ether 14 (16.84 g, 89.47 mmol, 93%) as a colorless liquid. IR (film): 1754 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=1.34 (d, J=7.0 Hz, 1H, CβH3), 1.39 (d, J=7.0 Hz, 2H, CβH3), 1.49 (m, 2H, CH2, THP–H3, 4, 5), 1.64 (m, 2H, CH2, THP–H3, 4, 5), 1.79 (m, 2H, CH2, THP–H3, 4, 5), 3.39 and 3.77 (2m, 2H, CH2, THP–H6), 3.68 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.15 and 4.37 (2 q, J=7.0 Hz, 1H, CαH), 4.64 (m, 1H, CH, THP–H2) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=18.7, 19.1, 25.3, 30.4, 51.7, 62.3, 69.9, 97.5, 173.5 ppm; MS (ESI): m/z (%)=206 (4), 211 ([M+Na]+, 100); HRMS (ESI): M++Na, found 211.0941; C9H16NaO4 requires 211.0946.

4.2.4. (2R)-2-(Tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)-propanoic acid (15)

A solution of methyl ester 14 (2.07 g, 11.00 mmol) was stirred in 1 M THF/LiOH (5:3 aq, 50 mL) for 5 h at 0 °C. Then the reaction mixture was acidified to pH 3 with 10% hydrochloric acid and extracted four times with ethyl acetate. The combined extracts were washed with a saturated NaCl solution (1×), dried with MgSO4, and filtered. A clear liquid (1.64 g, 9.40 mmol, 85%) of THP protected lactic acid 15 was obtained after evaporation of the solvent and drying in high vacuum. Further purification was not necessary. IR (film): 1735, 3103 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=1.45 (d, J=7.0 Hz, 1H, CβH3), 1.50 (d, J=7.0 Hz, 2H, CβH3), 1.55 (m, 2H, CH2, THP–H3, 4, 5), 1.70 (m, 2H, CH2, THP–H3, 4, 5), 1.83 (m, 2H, CH2, THP–H3, 4, 5), 3.52 and 3.86 (2m, 2H, CH2, THP–H6), 4.25 and 4.43 (2q, J=7.0 Hz, 1H, CαH), 4.65 and 4.73 (2m, 1H, CH, THP–H2), 9.76 (s, 1H, CO2H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=19.1, 19.6, 25.3, 30.3, 62.8, 70.1, 98.0, 178.1 ppm; MS (ESI): m/z (%)=89 (15), 101 (11), 173 ([M−H]−, 100), 174 (11); HRMS (ESI): M++Na, found 197.0785; C8H14NaO4 requires 197.0790.

4.2.5. (R)-3-Phenyl-2-(Tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yloxy)-propanoic acid (18)

To a solution of (d)-PhLac 17 (6.71 g, 40.38 mmol) in DCM (200 mL), 1 equiv of 3,4-dihydro-2H-pyrane (3.43 g, 40.38 mmol) and a solution of p-TsOH (605.16 mg, 3.15 mmol) and pyridine (251.65 mg, 3.15 mmol) in DCM (10 mL) were added. The mixture was stirred for 16 h at ambient temperature. After that the mixture was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was dissolved in diethylether (100 mL). The ether solution was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and evaporated. The crude product was dried in vacuo and was used in solid phase-synthesis without further purification. The reaction provides the product 18 as white solid with a yield of 100% (10.11 g, 40.21 mmol). IR (film): 1739, 3437 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ=1.48 (m, 2H, CH2, THP–H3, 4, 5), 1.60 (m, 2H, CH2, THP–H3, 4, 5), 1.67 (m, 2H, CH2, THP–H3, 4, 5), 3.00 (m, 1H, CβH2), 3.06, 3.27, 3.44, and 3.95 (4m, 2H, CH2, THP–H6), 3.19 (dd, J=4.1, 9.7 Hz, 1H, CβH2), 4.19 and 4.79 (2m, 1H, CH, THP–H2), 4.27 and 4.52 (2 dd, J=3.6, 5.6 Hz, 1H, CαH), 7.22–7.31 (m, 5H, Ar–H), 10.00 (s, 1H, CO2H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ=20.4, 24.8, 32.0, 38.5, 61.0, 74.2, 96.5, 126.7, 128.2, 128.3, 129.5, 129.8, 137.0, 176.5 ppm; MS (ESI): m/z (%)=184 (17), 251 ([M+H]+, 4), 268 ([M+NH4]+, 100); HRMS (ESI): M++Na, found 273.1097; C14H18NaO4 requires: 273.1103.

4.3. Solid-phase synthesis

4.3.1. Coupling of the first residue

A solution of PhLac–OTHP 18 (3 equiv), DIC (3 equiv), HOBt (3 equiv), and DMAP (3 equiv) in THF (1.0 mL/100 mg resin) was added to Wang-resin (500 mg, 1.07 mmol/g loading level), swollen in THF (1.0 mL/100 mg resin, 30 min, then solvent is removed), and stirred for 16 h at room temperature. The resin was washed three times (3 min each) with DCM (10 mL), acetone (10 mL), DCM (10 mL), and dried in high vacuum until constant mass was reached. The whole procedure was repeated once.

4.3.2. General procedure for the cleavage of the THP-protecting group

A suspension of the resin (500 mg) and 10 mL of p-TsOH in DCM/MeOH 97:3 (5 mg/mL) was agitated for 1 h at room temperature. After that time the solvent was removed and the resin was washed with the cleavage solution one time (3 min). The whole procedure was repeated once. The resin was filtered off, washed three times (3 min each) with DCM (10 mL), acetone (10 mL), THF (10 mL), and dried in high vacuum.

4.3.3. General procedure for ester couplings

A solution of N-Fmoc-N-methyl-leucine 12 (3 equiv), DIC (3 equiv), HOBt (3 equiv), and DMAP (3 equiv) in THF (1 mL/100 mg resin) was dropped at room temperature to the swollen resin (in THF, 1.0 mL/100 mg resin, 30 min, then the solvent was removed). The reaction was stirred for 16 h at room temperature. Then the resin was filtered off and washed three times (3 min each) with DCM (10 mL), acetone (10 mL), DCM (10 mL), and dried in high vacuum until constant mass was reached. The whole coupling and washing procedures were repeated once.

4.3.4. General procedure for the cleavage of the Fmoc-group

A suspension of the swollen resin (500 mg) and piperidine in THF (25%, 10.0 mL) was shaken for 30 min at room temperature. Then the resin was filtered off and washed three times (3 min each) with DCM (10 mL), acetone (10 mL), DCM (10 mL), and dried in high vacuum.

4.3.5. General procedure for amide couplings

A solution of the hydroxycarboxylic acid (15 or 18) (3 equiv), HATU (2 equiv), and DIEA (3 equiv) in THF (1.0 mL/100 mg resin) was added to the swollen resin (in THF, 1.0 mL/100 mg resin, 30 min, then the solvent was removed) and shaken for 16 h at room temperature. The resin was filtered off and washed three times (3 min each) with DCM (10 mL), acetone (10 mL), DCM (10 mL), and dried in high vacuum. The whole coupling and washing procedures were repeated once.

4.3.6. General procedure for the cleavage from the resin

The resin (500 mg) was suspended in a solution (10 mL) consisting of TFA/DCM 1:1 and agitated for 1.5 h at room temperature. The resin was filtered of and washed with DCM (10×, 10 mL each). The combined DCM rinses were washed with brine, dried with Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. Usually, the crude product was immediately used for the macrocyclization reaction without further purification.

4.4. Macrocyclization in solution

Cyclooctadepsipeptide PF1022A (1). BOPCl (62.0 mg, 0.24 mmol) was added to a solution of the crude linear octadepsipeptide 25 (196.80 mg content: 16%, 31.49 mg, 32.56 μmol) and DIEA (87 μl, 0.51 mmol) in DCM (200 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction was allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred for 24 h. Then the same amounts of BOPCl (62.0 mg, 0.24 mmol) and DIEA (87 μl, 0.51 mmol) were added and stirring was continued for another 24 h. After that time the mixture was washed twice with saturated NaHCO3 solution, dried with Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by flash-chromatography (toluene/isopropanol 20:1) to afford PF1022A 1 (25.0 mg, 26.34 μmol, 81%, based on the content of the raw linear octadepsipeptide 25) as a white solid. IR (KBr): 1660, 1739 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ=0.68–0.99 (m, 21H, CδH3-Leu, CβH3-Lac), 1.06–1.78 (m, 14H, CβH2-Leu, CγH-Leu), 1.28 (d, J=6.7 Hz, 3H, CβH3-Lac), 2.68, 2.77, 2.80, 2.85, and 2.91 (5s, 12H, NCH3), 3.08 (m, 2H, CβH2-PhLac), 4.41, 5.11, and 5.22 (3m, 4H, CαH-Leu), 5.01, 5.32, and 5.42 (3m, 2H, CαH-Lac), 5.52, 5.68, and 5.71 (3m, 2H, CαH-PhLac), 7.24–7.31 (m, 10H, Ar–H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d 6): δ=15.5, 16.3, 16.8, 20.4, 20.6, 20.8, 20.8, 20.9, 21.0, 23.0, 23.1, 23.2, 23.2, 23.4, 23.9, 24.2, 24.3, 24.3, 24.4, 28.9, 30.1, 30.1, 30.2, 30.3, 30.6, 35.7, 36.3, 36.5, 36.6, 36.7, 36.7, 36.8, 37.1, 37.3, 53.0, 53.2, 53.3, 56.4, 66.7, 67.5, 67.7, 70.1, 70.9, 71.0, 126.7, 126.7, 126.8, 128.1, 128.2, 128.2, 129.5, 135.1, 135.2, 135.9, 169.0, 169.0, 169.3, 169.5, 169.7, 170.2, 170.3, 170.7, 170.9 ppm; MS (ESI): m/z=475 (4), 950 ([M+H]+, 1), 966 ([M+NH4]+, 100), 971 (23); HRMS (ESI): M++Na, found 971.5351; C52H76N4NaO12 requires 971.5352.

Acknowledgements

Generous financial support by Bayer Animal Health GmbH is gratefully acknowledged.

References and notes

- 1.Tomoda H., Doi T. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:32–39. doi: 10.1021/ar700117b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemmens-Gruber R., Kamyar M.R., Dornetshuber R. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009;16:1122–1137. doi: 10.2174/092986709787581761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng Y.-Q. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:471–477. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monma S., Sunazuka T., Nagai K., Arai T., Shiomi K., Matsui R., Omura S. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5601–5604. doi: 10.1021/ol0623365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu Y., Wijeratne E.M.K., Espinosa-Artiles P., Gunatilaka A.A.L., Molnár I. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:345–354. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scherkenbeck J., Jeschke P., Harder A. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002;2:759–777. doi: 10.2174/1568026023393624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeschke P., Iinuma K., Harder A., Schindler M., Murakami T. Parasitol. Res. 2005;97:11–16. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1439-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coin I. J. Pept. Sci. 2010;16:223–230. doi: 10.1002/psc.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teixido M., Albericio F., Giralt E. J. Pept. Res. 2005;65:153–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2004.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koshla M.C., Smeby R.R., Bumpus F.M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:4721–4724. doi: 10.1021/ja00768a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coin I., Beerbaum M., Schmieder P., Bienert M., Beyermann M. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3857–3860. doi: 10.1021/ol800855p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koo S.Y., Wenger R.M. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1997;80:695–705. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raman P., Stokes S.S., Angell Y.M., Flentke G.R., Rich D.H. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:5734–5735. doi: 10.1021/jo980889q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jastrzabek K.G., Subiros-Funosas R., Albericio F., Kolesinska B., Kaminski Z.J. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:4506–4513. doi: 10.1021/jo2002038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wischnat R., Rudolph J., Hanke R., Kaese R., May A., Theis H., Zuther U. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:4393–4394. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thern B., Rudolph J., Jung G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:2307–2309. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020703)41:13<2307::AID-ANIE2307>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albericio F., Burger K., Ruíz-Rodríguez J., Spengler J. Org. Lett. 2005;7:597–600. doi: 10.1021/ol047653v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albericio F., Burger K., Cupido T., Ruiz J., Spengler J. Arkivoc. 2005:191–199. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee B.H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:757–760. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyashita M., Nakamori T., Akamatsu M., Murai T., Miyagawa H., Ueno T. Pept. Chem. 1996;34:137–140. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spengler J., Koksch B., Albericio F. Pept. Sci. 2007;88:823–828. doi: 10.1002/bip.20858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deechongkit S., Dawson P.E., Kelly J.W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:16762–16771. doi: 10.1021/ja045934s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuisle O., Quiñoá E., Riguera R. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:8063–8075. doi: 10.1021/jo981580+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies J.S., Howe J., Jayatilake J., Riley T. Lett. Pept. Sci. 1997:441–445. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuisle O., Quiñoá E., Riguera R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:1203–1206. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang S., Govender T., Norström T., Arvidsson P.I. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:6918–6920. doi: 10.1021/jo050916u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donners M.P.J., Hersmis M.C., Custers J.P.A., Meuldijk J., Vekemans J.A.J.M., Hulshof L.A. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2002;6:606–610. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Y., Duan X., Li M., Jiang M., Zhao G., Meng Y., Chen L. Molecules. 2005;10:259–264. doi: 10.3390/10010259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zubia A., Mendoza L., Vivanco S., Aldaba E., Carrascal T., Lecea B., Arrieta A., Zimmerman T., Vidal-Vanaclocha F., Cossío F.P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:2903–2907. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim H.O., Olsen R.K., Choi O.S. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:4531–4536. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carpino L.A., El-Faham A. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:6813–6830. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pon R.T., Yu S., Sanghvi Y.S. Bioconjugate Chem. 1999;10:1051–1057. doi: 10.1021/bc990063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ingram A., Stokes R.J., Redden J., Gibson K., Moore B., Faulds K., Graham D. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:8578–8583. doi: 10.1021/ac071409a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nidhino N., Xu M., Mihara H., Fujimoto T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1992;65:991–994. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith R.A., Bobko M.A., Lee W. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998;8:2369–2374. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00428-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischer P.M. J. Pept. Sci. 2003;9:9–35. doi: 10.1002/psc.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lengweiler U.D., Fritz M.G., Seebach D. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1996;79:670–701. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi M., Nanba T., Toyama T., Saito A. Annu. Rep. Sankyo Res. Lab. 1994;46:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scherkenbeck J., Plant A., Harder A., Mencke N. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:8459–8470. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winter M., Warrass R. In: Combinatorial Chemistry. Fenniri H., editor. Oxford University; Oxford: 2000. pp. 117–138. [Google Scholar]