Abstract

Feline angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (fACE2) gene was amplified from domestic cat lung with RT-PCR, cloned and sequenced. The complete coding region is 2418 bp in length and is the closest to human ACE2 among known ACE2 homologs of non-primate animals. The N terminal fragment 19– 367 aa was expressed in Escherishia coli. Both Western blotting and ELISA demonstrated that fACE2 could react with SARS-CoV S1 protein as efficiently as ACE2 of Vero E6 cells did.

Keywords: Feline angiotensin converting enzyme 2(fACE2), SARS-CoV, Spike protein, Receptor, Cats

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) was identified as the functional receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in humans (Li et al., 2003, Li et al., 2004, Li et al., 2005a, Li et al., 2005b). ACE2 is an 805 amino acid carboxy-metalloprotease and plays a significant role in cardiovascular physiology (Eriksson et al., 2002). Several lines of findings demonstrated N terminal of human ACE2 (hACE2), independent of proteolytic site, contains the binding domain of SARS-CoV S1, the receptor binding protein (Hofmann et al., 2004, Li et al., 2003, Yang et al., 2006). Furthermore, the replication limitation of SARS-CoV in non-primate animals is determined by the natural ACE2 homologs from non-primate animals such as mice, rats and palm-civets (Li et al., 2004, Li et al., 2005a, Li et al., 2005b). SARS-CoV could infect domestic cats (Martina et al., 2003, Ng, 2003). This study was aimed to clone fACE2 gene from cat tissue and revealed the potential ability of fACE2 to mediate SARS-CoV infection of cats.

Three nine-month-old domestic cats were euthanized. The total RNA of lungs was extracted to amplify fACE2 gene with RT-PCR. Four fragments of fACE2 gene were amplified with the primers based on hACE2 gene (GenBank accession: AF241254) and the resultant fACE2 sequence obtained by the previous steps. The primers for fragment 1 (440–1495 nt in hACE2 gene) are F1: 5′-AGCAAACGGTTGAACAC-3′, and R1: 5′-AAGACCATCCACCTCCAC-3′ specific to hACE2. Fragment 2 (2–831nt in hACE2 gene) was amplified with primers F2: 5′-GCCCAACCCAAGTTCAAAGGCT-3′ specific to hACE2 gene and R2: 5′-AAGGGTAGGTATCCATCAAC-3′ specific to fragment 1. Fragment 3 from 1287 nt to 2504 nt was obtained with primers F3: 5′-AGATCATGTCACTTTCTGCG-3′ specific to fragment 1 and R3: 5′-ATCATCAGTGTTTTGGAATC-3′ specific to hACE2 gene. Fragment 4 from 2298 nt to the 3′ end was amplified using the primer F4 5′-TGATTGTTTTTGGGGTCGT-3′ based on fragment 3 and 3′ sites adaptor provided by 3′ Full Race Core Set (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). As a result, the coding region of fACE2 gene is spliced which is 2418 bp in length, same as that of human (GenBank accession: AF241254), mouse (GenBank accession: AB053181) and rat ACE2 (GenBank accession: AY881244). It encodes 805 amino acids including 17aa of signal peptide sequence and C-terminal transmembrane domain. The similarities to that of human, mouse and rat ACE2 are, respectively, 85%, 84% and 84% at the nucleotide level and 85%, 81% and 81% at the deduced amino acid level. The completed sequence has been submitted to GenBank (GenBank accession: AY957464).

Three amino acid regions of ACE2 were suggested to be critical to its association to SARS-CoV S protein (Li et al., 2005a, Li et al., 2005b). The three regions include α1 ridge (30–41aa), loop and α3 (82–93aa), loop and β5 (353–357aa). The sequence of fACE2 in these three regions is closest to that of hACE2 among known sequences of cat, palm-civet, mouse and rat ACE2 (Fig. 1 ). Meanwhile, among the deduced 18 amino acid residues that contact SARS-CoV receptor binding domain (RBD), fACE2 share the most of them (Li et al., 2005a, Li et al., 2005b). The number of different amino acids between hACE2 and cat or civet or mouse or rat ACE2 was, respectively, 3, 8, 9, and 11.

Fig. 1.

The comparison of three amino acid regions in ACE2 homologs of different species critical to SARS-CoV S1 association. The single letters represent the amino acid residues and the bold letters represent the different residues from those of human ACE2.

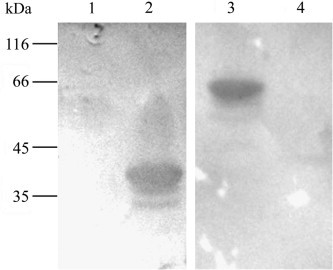

The fragment from 19 aa to 367 aa (fACE19–367) excluding signal peptide and proteolytic site was amplified with primers F5: 5′-GATCCATGGGCTCCACCACTGAAGAACTG-3′ (the underlined denoted Nco I recognition site) and R5 5′-GCATCTCGAGAACAGACACAAAGAATTTC-3′ (The underlined denoted Xho I recognition site), subcloned into pET28a, and expressed in Escherishia coli BL21(DE3) after induction with IPTG 0.08 mmol/L for 3.5 h at 37 °C. The His-tagged fACE19–367 was extracted from the inclusion bodies and purified by nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid agarose affinity chromatography (Novagen). SDS–PAGE detected the expression at the size of about 42 kDa as expected. Both fACE219–367 and Vero E6 ACE219–367 previously expressed by this laboratory (Yang et al., 2006) were separated by SDS-PAGE (12%).Western blot assay was performed with goat polyclonal antibody to hACE2 (R&D) and HRP-coupled goat anti-rabbit IgG (Southern Biotech) (Sambrook et al., 1989). This result showed that fACE219–367 could cross-react with the antibody to hACE2. Alternatively, the purified SARS-CoV S1 protein, rabbit antiserum to S1 prepared by this laboratory (Fei et al., 2006) were sequentially overlaid on the blotted membrane. This ligand blotting assay indicated that S1 could detect His-tagged fACE219–367 of 42 kDa, as well as GST-ACE219–367 of 65 kDa from Vero E6 cells (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Binding of ACE2 to SARS-CoV S1. His-tagged fACE219–367 and GST- Vero E6 ACE219−367 were blotted onto cellulose membrane, probed by SARS-CoV S1 protein, overlaid by anti-S1 antibody. Lanes 1 and 4 represent E. coli transformed by blank vector as negative controls. Lanes 2 and 3 represent His-tagged fACE219–367 and GST-Vero E6 ACE219−367 of 65 kDa. The molecular masses were marked on the left.

Both fACE2 and Vero E6 ACE2(vACE2) fragments of 1.0 μg were coated in triplicate in a 96-well plate, and followed by incubation with S1 protein 1.5 μg/ml. E. coli BL21(DE3) transformed with the blank vector was sonicated and taken as the negative control. Finally, the 1000-fold diluted sera of three convalescent SARS patients offered by Hubei Center of Disease Control, 4000-fold diluted HRP-coupled goat polyantibody to human IgG and TMB solution were sequentially added to develop the reaction. The experiment was independently repeated four times. As a result, the mean OD630 values for coated vACE2 wells were 0.9094 ± 0.1487, for coated fACE2 wells were 0.8601 ± 0.1002, while those of negative control wells were 0.1598 ± 0.0350. There is no difference in the binding ability of vACE2 and fACE2 to SARS-CoV S1 (P > 0.01). However, there is significant difference in OD values between ACE2 and negative control wells (P < 0.01).

Taken altogether, we cloned fACE2 gene from domestic cat lung and demonstrated that it possesses the same length of hACE2 and shares a similarity of 85% with that of hACE2 which was confirmed by its cross-reactivity with anti-hACE2 antibody. Among the ACE2 homologs in cats, civets, mice, and rats (Li et al., 2005a, Li et al., 2005b), fACE2 is evolutionarily closest to hACE2. Both fACE2 and vACE2 could efficiently bind to S1. This would be of significance in zoonotic transmission of SARS-CoV from animals to humans.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by China National Basic Research Program (China “973 Program) (2003 CB514122).

References

- Eriksson U., Danilczyk U., Penninger J.M. Just the beginning: novel functions for angiotensin-converting enzymes. Curr. Biol. 2002;12(21):R745–R752. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei Xiaozhan, Lu Haisong, Guo Hongyan, Tan Yadi, Chen Huanchun, Guo Aizhen. Expression of SARS-CoV spike protein fragment of S144-643 and its immunogenicity. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2006;25(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann H., Geier M., Marzi A., Krumbiegel M., Peipp M., Fey G.H., Gramberg T., Pohlmann S. Susceptibility to SARS coronavirus S protein-driven infection correlates with expression of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 and infection can be blocked by soluble receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;319(4):1216–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S.K., Berne M.A., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J.L., Luzuriaga K., Greenough T.C., Choe H., Farzan M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426(6965):450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Greenough T.C., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J.L., Farzan M., Choe H. Efficient replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in mouse cells is limited by murine angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Virol. 2004;78(20):11429–11433. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11429-11433.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Zhang C., Sui J., Kuhn J.H., Moore M.J., Luo S., Wong S.K., Huang I.C., Xu K., Vasilieva N., Murakami A., He Y., Marasco W.A., Guan Y., Choe H., Farzan M. Receptor and viral determinants of SARS-coronavirus adaptation to human ACE2. EMBO J. 2005;24(8):1634–1643. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Li W., Farzan M., Harrison S.C. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309(5742):1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martina B.E., Haagmans B.L., Kuiken T., Fouchier R.A., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Van Amerongen G., Peiris J.S., Lim W., Osterhaus A.D. Virology: SARS virus infection of cats and ferrets. Nature. 2003;425(6961):915. doi: 10.1038/425915a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng S.K. Possible role of an animal vector in the SARS outbreak at Amoy Gardens. Lancet. 2003;362(9383):570–572. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14121-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J., Fritsch E.F., Maniatis T. second ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1989. Molecule Cloning:A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Guo-liang, Fei Xiao-zhan, Chen Huan-chun, Guo Ai-zhen. Prokaryotic expression of SARS-CoV receptor ACE2 in E. coli and identification of its functional domain. Chinese J. Virol. 2006;22(2):118–122. [Google Scholar]