Abstract

Humans are increasingly being challenged with numerous forms of man-made and natural emergency situations. Emergencies cannot be prevented, but they can be better managed. The successful management of emergency situations requires proper planning, guided response, and well-coordinated efforts across the emergency management life cycle. Literature suggests that emergency management efforts benefit from well-integrated knowledge-based emergency management information systems (EMIS). This study presents a systematic review of papers pertaining to the application of knowledge-driven systems in support of emergency management that have been published in the last two decades. Our review presents two major findings. First, only limited work has been done in three EMIS-knowledge management system (KMS) subdomains: (i) definition, (ii) use, and (iii) methods. Second, only limited research has been done in embedding roles in KM systems. We highlight role alignment to the 12 fundamental roles, as called for by Turoff et al. (2004), in the context of creating dynamic systems in aid of emergency management efforts. We believe that these two findings warrant the attention of the research community.

Keywords: Roles, Emergency management, Information systems, Disaster, Knowledge management systems, Forecasting

Highlights

► We examined knowledge gaps exist in applied KMS for disaster/emergency. ► Only 1% of 8000 KM papers had focused on KMS for disaster or emergency. ► We reviewed 51 applied KMS papers that focused on disaster or emergency. ► Only half of the applied papers explicitly used the term “Knowledge Management”. ► We model design guidelines for KMS/EMIS.

1. Introduction

Disaster is a common term today. Disaster is defined as ‘a social crisis situation’ [1], ‘a deadly’ event [2], usually unexpected and unanticipated and cause human suffering [3]. [4] provides a list of attributes of disaster: suddenly occurs, demand quick reactions, creates uncertainty and stress, threaten the reputation of organization and escalates in intensity. Disaster management involves activities such as mitigation, risk reduction, prevention, preparedness, response and recovery [5]. Managing disaster is vital as it threatens organizational goals and permanently impairs the earning power [6], [7]. Prominent issues in disaster management are the need for common platform to enable seamless flow of information and lack of integrated system to support emergency activities.

Over the last decade alone (2000 to 2010), the average death toll rose sharply due to the increasing frequency of disasters, especially in developing countries. The United Nations reported that in 2010 alone, 373 earthquakes, floods, cyclones, volcanic eruptions, and droughts occurred, which affected 208 million people around the world, killing nearly 300,000, and costing US$110 billion in losses [8], [9]. Earthquakes in Haiti (12 January), Chile (27 February), and China (13 April), flooding in Pakistan (July to September), and heat wave in Russia (July to September) were the five most devastating natural catastrophes in 2010, which claimed 280,000 lives and US$52 billion worth of losses [10]. A World Vision report rationalized these phenomena by quoting climate change as a new driver of disaster risk, which increases both hazards and vulnerabilities [11]. Although stopping disasters from occurring is impossible, being prepared with the right knowledge and information on disasters is possible.

1.1. Emergency management information systems (EMIS)

In 1971, the OEP was assigned the task of monitoring a new form of crisis called the“Wage Price Freeze” [12]. This new role for the OEP included among others, to “monitor nationwide compliance, examine and determine requests for exemptions and prosecute violations” (p. 5) in relation to wage and price changes in the economy. This led to the advent of a flexible system called the Emergency Management Information System and Reference Index (EMISARI). EMISARI was a system designed to facilitate effective communication between people involved in monitoring the Wage Price Freeze situation. The system was designed to integrate people and data into a common platform that could be updated regularly by people who were non-technical administrators [12]. The EMISARI system was flexible and enabled several hundreds of people to collaborate in responding to a crisis [12]. [12] presented complete design principles and guidelines for developing an EMIS. [13, p.6] claimed that “EMISARI incorporated many of the features called for today under the current rubric of knowledge systems”. The crux of this paper is 9 design premises, 5 components of DERMIS conceptual design, 8 general design principles and specification and 3 supporting design considerations and classifications. DERMIS is a perfect example to describe an EMIS.

Other literature classifies crisis management information systems as Emergency Information Systems (EIS) [14]. EIS is defined as any system that is used “by organisations to assist in responding to a crisis or disaster situation” (p. 2148). [14] further adds that an EIS should be designed to: support communication during crisis response; enable data and gathering analysis; and support decision-making [14]. [7] documented vital observation with the use of EIS during the massive earthquake that hit Kobe, Japan, several years ago. Subsequently, other forms of Emergency Management Information Systems include the following:

-

•

Sahana Disaster Management Systems for Tsunami (2004), by Sarvodaya.org during Tsunami (2004) [15], [16]

-

•

Information Management System - IMASH for Hurricane Disasters [17]

-

•

Digital Typhoon, a KMS to provide information for typhoons [18]

-

•

PeopleFinder and ShelterFinder [19]

-

•

Strong Angel III (2006), United Nations Development Program [9]

-

•

Tsunami Resource and Result Tracking Systems [20]

-

•

Case Management Systems in Singapore used during SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) [21], [22]

-

•

NIMS (National Incident Management Systems) in USA [23]

-

•

DesInventar System, a historical disaster database and post-disaster damage data collection tool, a project by UNDP and countries such as Latin America, Orissa and South Africa are currently using this system [24], [25], [26]

-

•

Google's Person Finder Tool (launched in 2010) that helped in registering and locating earthquake survivors in Japan (2011), Christchurch (2011) and Haiti (2010) [27].

1.2. Knowledge and knowledge management systems

[28] referred to knowledge as a ‘justified personal belief’ that directly linked with personal capacity of an individual to take effective action. Knowledge can be tacit or explicit [29]. Managing both tacit and explicit knowledge is the challenge of knowledge management (KM). Tacit knowledge is the knowledge that cannot be expressed in words whereas explicit knowledge refers to knowledge that can be expressed in words and numbers [29], [30]. KM is defined as an activity of helping an organization to create, capture, codify, store, share and apply knowledge effectively. KM in information system perspective refers to the effective tool to enable the knowledge management processes. In this context, a knowledge management system (KMS) is the key enabler of KM and is applied in nature.

Insights about knowledge and managing knowledge have been described and discussed over the years. However, research on KMS is still limited [30]. [30] assert that practitioners value KM as it leads to desirable organizational benefits. Fundamentally, KM is enabled by an effective information technology (IT) solution. [31] supports the notion that despite the obvious relevance of IT for KM, there has been relatively little work on the application of software to this area. KM in IS perspective refers to the effective tool to enable the knowledge management processes. In this context, a knowledge management system (KMS) is the key enabler of KM and is applied in nature. Many researches on KM/KMS defined it as IT-based systems developed to support and enhance knowledge creation, storage/retrieval, transfer and application [30], [32], [33].

KMS includes knowledge-based systems, document management systems, semantic networks, object oriented and relational databases, decision support systems (DSS), expert systems and simulation tools [34]. Any one or combination of these tools can be designed as effective KMS. DSS, database, groupware and intranet are among the tool of choice by many researchers. For example, DSS was used by [35], [36] as the overall representation of their KMS. [37], [38], [33] used database concepts to form a KMS.

1.3. KMS-EMIS relationship

However, literature on EMIS suggests that the designers of a particular system aimed at supporting disaster management, may not necessarily use the terms and theories in the context of KMS. The inherent features of such systems do in real fact support the goals of a KMS for managing emergencies/disasters. A case in point would be the seminal work by [12], [39] who clearly demonstrate that both the ERMIS and the subsequently developed DERMIS were in fact driven by KM dimensions and considerations. In the realm of disaster/emergency management information system, [12], [13], [39], [40] researches seem to be instrumental to all other research.

1.4. Role of knowledge management systems in disaster management

Dealing with disaster situations such as earthquakes, terror threats and other forms of natural or man-made disasters are examples of complex and dynamic environments [41]. The challenge for an organization is to develop a KMS that can easily adapt to change in dealing with uncertainties [41], [42]. [43] suggests several attributes that KMS should have in helping organizations deal with complex and dynamic environments. These include knowledge management systems that:

-

•

Provide a shared knowledge space with use of consistent and well defined vocabulary.

-

•

Model and explicitly represent knowledge.

-

•

Permit collaborative efforts between employees.

-

•

Allow reusable knowledge.

-

•

Empower employees based on a knowledge sharing culture.

Knowledge management involves various events and activities and there is a significant role for information technology in this effort [44]. IT can support the process of knowledge creation, sharing, dissemination and creation of a useful organizational memory system to enhance emergency planning and response [30]. Knowledge management systems can assist organizations in dealing with dynamic and complex situations such as in dealing with emergencies [41], [42], [45].

For any disaster response center, issues such as managing different stakeholder expectations, priorities, and the various resource and skill sets they bring into an actual crisis response mode, is complex and dynamic. This could lead to difficulties in making accurate decisions, under time-pressured and intense situations, while responding to a particular disaster situation. In this context, we suggest that a KMS can be used for capture and then re-use of specific crisis response knowledge which can support decision making when a crisis actually occurs. The practice of selectively applying knowledge from previous experiences during turbulent moments of decision making, to current and future decision making activities with the express purpose of improving the organization's effectiveness, would be possible via a KMS. In addition, we further add that given the dynamic nature of disaster situations, coupled with different inputs and requirements from various stakeholder groups, a disaster manager and center therein, is subject to information overload, which can prevent timely and accurate decision making. A well tested and implemented KMS in this context can help to decide what to look at, what decisions to focus on, and what decisions can be made automatically and/or in advance.

[46, p. 5] defines knowledge management, KM, as the practice of selectively applying knowledge from previous experiences of decision-making to current and future decision making activities with the express purpose of improving the organization's effectiveness. KM is an action discipline; knowledge needs to be used and applied for KM to have an impact. [46] further stress that knowledge about past situations are relevant to generate current procedures and forecast future responses. During an emergency situation, lessons learned and understanding of what works best in given situations (both examples of knowledge) [46] enables emergency managers to be prepared with workable plans to ensure smooth decision making process.

Emergency management involves extensive coordination, communication, and integration within a dynamic and ad hoc environment. The unique nature of emergency situations warrants KMS deployment to support dynamic knowledge processes. In the realm of emergency management, KMS enables the collection, retrieval, dissemination, and storage of the right knowledge to be used in the right place and at the right time. An integrated knowledge solution will greatly improve disaster management efforts, especially in the context of disasters in a highly turbulent environment. However, an adequate coping mechanism must be present to enable such knowledge to transform into life-saving knowledge. Such a mechanism was evident in various KMS tools that were used for emergency management during Hurricane Katrina in North America [19], [47], [48] and the Indian Ocean tsunami [49], [50], [51], both in 2004. Hence, the research aims to delve deeper into the literature in the KMS context for disasters and explore the research gaps.

We examined 141 papers pertaining to knowledge management systems (KMS) in support of disasters, and suggest that two main gaps exist in the current literature in this domain. First, only limited work has been done in three EMIS-KMS subdomains: (i) definition, (ii) use, and (iii) methods. Second, we examined to ascertain if prior works on KMS applied to disaster management relate to the 12 fundamental roles required in a dynamic system to support disasters, as called for by [12]. Our findings suggest that a significant gap exists in this area. We believe that these two findings warrant the attention of the research community.

2. Review methodology

Our literature review was based on the five stages of systemic review proposed by [52], which entails five phases:

-

•

Planning the review—reported in Section 2;

-

•

Identifying and evaluating studies—reported in Section 2;

-

•

Extracting and synthesizing data—reported in Section 3;

-

•

Reporting descriptive findings—reported in Section 3; and

-

•

Utilizing the findings to inform research and practice—reported in Section 4.

2.1. Planning the review

The main goal of this review is to ascertain the nature and form of research in relation to applied KMS in aid of disaster. We aim to offer researchers a comprehensive review of previous works related to applying KMS to support disaster management, particularly in the types of tools that have been developed and tested and the works done to map these systems to the roles that emergency responders require in relation to system use. The review process outcome is to offer emergency management/KM communities a series of research ideas to move the field forward.

2.2. Identifying and evaluating studies

One main issue that hindered the identification of all papers that analyzed the KMS role for disasters is that most of the papers do not explicitly call the type of information systems used as KMS. The systems are referred to based on their role for business, such as decision support system (supports decision making), expert systems (guide novice users), database systems (systematically organize data), document management systems (manages documents), semantic web/ontology (organizes the terms), and Intranets (provide various services to members), among others. However, the KMS definition covers all of these roles and the combination of the different roles to support knowledge process [34], [53]. Therefore, as the first step, we decided to examine the number of papers for the selected keywords. The keywords include key concepts that are general (KM) toward more specific keywords (KMS for disaster/emergency).

Our focus for this review is to analyze KMS applied research. Applied-KMS is referred to as studies based on an actual/real KMS for disaster that exists. We further classified the applied-KMS concept to systems that were either self-developed (by the author and project team) or developed by authors who examined the use of such systems to prove their propositions in mapping KM ideals to the emergency management context.

2.2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following are the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the paper search:

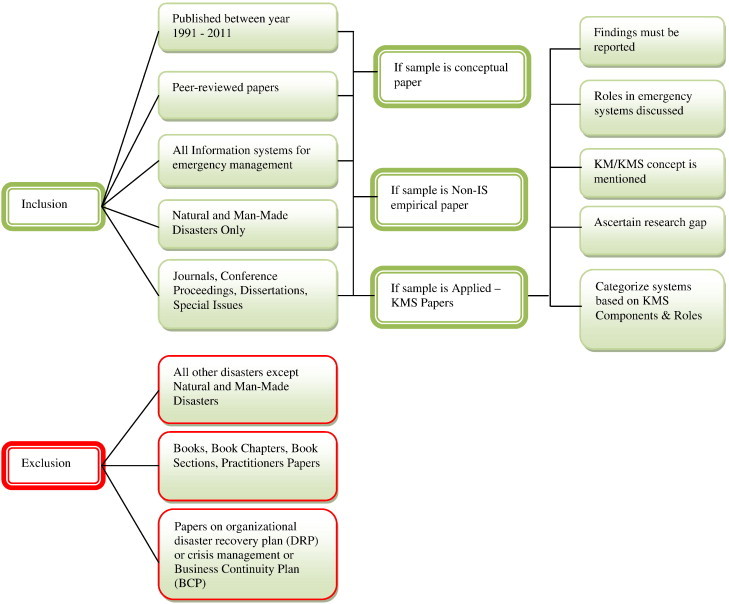

Fig. 1 summarizes our criteria for the inclusion/exclusion of papers for our analysis. We only selected papers that were published in the last two decades, peer-reviewed, linked to EMIS, focusing on either man-made or natural disasters, of scholarly origin, and applied in nature (i.e., actual systems developed or examined in a KM context).

Fig. 1.

Inclusion and exclusion for the systematic review.

2.2.2. Keywords

We focused on two main research areas: (1) Knowledge Management Systems and (2) Disaster/Emergency. For the first area, we included terms such as “knowledge management,” “knowledge management systems,” “knowledge management system (without “s”),” and “KMS” and “KM” (abbreviations) that many authors interchangeably use in relating their research toward KM concepts. The next key terms used were “disaster” and “emergency” [12], [54]. Each keyword set was searched individually, and later, combined with other keywords. Table 1 presents the keyword sets used for this research.

Table 1.

Focus categories and component title keywords used in construction of KMS disaster related articles.

| Focus Category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Knowledge management |

2 Knowledge Management Systems |

3 Disaster |

4 Emergency |

5 KMS for Disaster |

6 KMS for Emergency |

| KM or Knowledge management | KMS or Knowledge management system or Knowledge management systems | Disaster or Disasters | Emergency or Emergencies | Knowledge Management Systemsor Knowledge Management System or KMS and Disaster | Knowledge Management Systemsor Knowledge Management System or KMS and Emergency |

Note: Keyword sets 1–4 were searched to highlight the research gap in KMS for disaster.

2.2.3. Search strategies

We set out three strategies to sift through papers that discuss applied KMS for disasters.

-

Stage 1

Online Database

The first strategy is to search in online databases. We first searched two online databases that encompass a vast range of IS research, as well as disaster-related research.-

i.Association of Information Systems Electronic Library (AISeL)The reason for choosing AISeL is given that major IS journals such as the Journal of the Associations of Information Systems (JAIS), MIS Quarterly (MISQ), Information Systems Journal (ISJ), Journal of Information Technology Theory and Appplication (JITTA), Communications of the Association of Information Systems (CAIS), Pacific Asia Journal of the Association of Information Systems (PAJAIS), Business & Information Systems Engineering (BISE), and Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems (SJIS), and conference proceedings such as Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS), International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems (MCIS), and Pacific-Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS) are listed in this library. We launched our first search in this online database that requires subscription. Keywords were entered based on Table 1. We gathered all peer-reviewed papers within the time period selected. We realized that our search for “KMS + disaster” or “KMS + emergency” did not list all papers that contain the two sets of keywords; instead, the list yielded many irrelevant papers for the aforementioned keywords. Another problem that we encountered was the results were mostly from conference proceedings, and very few were from journals.

-

ii.EmeraldWe proceeded to search the Emerald online database, which has a large number of disaster-related papers. Emerald has more than 35,000 full-text articles encompassing over 100 reputable management journals. We recorded the journal results to ensure that we collect only peer-reviewed papers, as the advanced search of Emerald does not separate papers based on peer-review status. We had to search based on keyword combination within the journal repository. We recorded all results in the keywords table.

Results for “KMS + disaster” and “KMS + emergency” were very large. We went through each listed paper so as not to miss the important ones. We also faced problems similar to those we faced when we used AISeL. The search using Emerald did not list papers with the given keywords only. Our selection criterion, therefore, was to accept all papers that discussed KMS/IS for disasters and reject all papers that discussed either KMS or disasters only, without one relating to the other. Although the search by disaster/emergency yielded a large number of papers from the total number of papers listed in AISeL for disaster and emergency, only 0.7% were related to “KMS + disaster” and only 0.4% were related to “KMS + emergency.” The Emerald list has slightly more relevant papers than AISeL, with 5% of the papers for “KMS + disaster” and 5% for “KMS + emergency”. The overall search results by online databases are shown in Table 2 .

-

i.

-

Stage 2

Individual Journals/Conferences

Worried that we might lose a number of important papers in the second stage, we decided to sift through each of the journals and conferences in AISeL, and the journals that frequently appeared in the Emerald general search, such as Disaster Prevention and Management (DPM). We managed to collect a number of papers that were not listed in the general search within the selected online database. We narrowed the search by using the International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) of the individual journals in the search.

Aside from the journals listed in AISeL and DPM, we have purposefully selected papers from the International Journal of Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management (IJISCRAM), which provides an outlet for innovative research in IS for crisis response and management. IJISCRAM has published four volumes from 2009 to 2012 (12 issues thus far). The journal is listed in the InfoSci-Journal online database, a premier research database featuring over 145 cutting-edge journals in information science and technology. Fifty papers have been published in the journal between 2000 and 2011. An advanced search launched in the InfoSci-Journal online database using the keywords listed only one paper under the “KMS + disaster/emergency” keywords. Given our intention to find research gaps, we decided to analyze the 50 papers to learn more about the nature of the papers in this journal. Other journals related to disaster and emergency that we decided to include in this research are Technological Forecasting and Social Change (TFSC), Disaster Management and Response (DMR), and Journal of Enterprise Information Management (JEIM).

Aside from the IS conferences listed in AISeL, we selected two more conference proceedings for this analysis, namely, Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management Conference (ISCRAM) and Hawaii International Conference on System Science (HICSS). ISCRAM and HICSS are renowned conferences in IS. ISCRAM brings together a research community dedicated to the promotion of exchange of knowledge and the deployment of IS for crisis management. ISCRAM has organized nine conferences to date. We selected only the papers from the 2011 ISCRAM conference proceedings due to time constraints and the limited scope of this paper. HICSS is another prominent IS conference held on an annual basis in Hawaii. Although it started in 1995, HICSS only began to have a special track in emergency management information systems in 2006. We searched through the HICSS papers starting from 2006 to 2011. Overall, ISCRAM, HICSS, CAIS, and AMCIS are the four conferences that have relevant papers for this analysis.

-

Stage 3

Special Issues

We then searched for KMS papers on disasters to include special issues. We searched through Google with the same keywords. We added “special issue” to obtain special issues only. We only checked up to the second page of the Google search results due to many irrelevant hits. We found that combined-keyword search such as “special issues + knowledge management systems + disaster/emergency” gives less relevant hits compared to search with combined keywords that are more general, such as “special issue + disaster/emergency.” We collected 11 special issues and from which, only five have published papers that are IS-related. The rest are either non-IS papers, general disaster issues, or engineering papers. The total number of relevant papers from this source is 19.

The results based on all the abovementioned sources and keyword sets in Table 1 are shown in Table 3 . A total of 8408 papers were listed when the keyword “KM” was used. When we searched for KMS, the number dropped to 751. When we used the keyword sets “KMS + disaster” and “KMS + emergency,” 123 papers were generated. After a careful selection based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which is described in the following section, 141 papers pertaining to KMS and disaster/emergency were identified.

Table 2.

Search result by online database for KMS & Disaster.

| Focus Category (No. of Papers) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online Database | Disaster | Emergency | KMS + Disaster | KMS + Emergency |

| AISeL | 2050 | 2993 | 14 (0.7%) | 11 (0.4%) |

| Emerald | 5704 | 6205 | 287 (5%) | 283 (5%) |

Note: The percentage for KMS + disaster is based on total result for keyword ‘disaster’ and for KMS + emergency is based on total result for keyword ‘emergency’.

Table 3.

Summary of search results.

| Results by Search |

Unit of Analysis (Selected Papers) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Management (KM) | Knowledge Mangement Systems (KMS) | Disaster | Emergency | KMS + Disaster | KMS + Emergency | ||||

| No. | Journals | Online Database | |||||||

| 1 | JITTA | AISeL | 33 | 10 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 2 | MISQ | AISeL | 72 | 21 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | ISJ | AISeL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | CAIS | AISeL | 65 | 48 | 66 | 77 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | JAIS | AISeL | 41 | 10 | 14 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | PAJAIS | AISeL | 14 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | IJISCRAM | InfoSci | 15 | 1 | 20 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 48 |

| 8 | TFSC | ScienceDirect | 115 | 13 | 150 | 85 | 7 | 5 | 2 |

| 9 | DMR | ScienceDirect | 1 | 0 | 261 | 209 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | DPM | Emerald | 3345 | 9 | 1728 | 984 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| 11 | JEIM | Emerald | 4299 | 267 | 14 | 16 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Conferences | |||||||||

| 1 | AMCIS | AISeL | 168 | 286 | 176 | 224 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2 | ICIS | AISeL | 240 | 85 | 47 | 54 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 3 | ISCRAM (2011 Full Papers) | 32 | 31 | ||||||

| 4 | HICSS (All papers in 1994–2011) | 30 | 18 | ||||||

| Special Issues | Journal Name | ||||||||

| 1 | Special Issue on Disaster | Disaster Prevention and Management | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2 | Special issue on Advances in Multi-Agency Disaster | IS Frontiers | 5 | 5 | |||||

| 3 | Special Issue on Sensors for Disaster and Emergency Management Decision Making | Sensors | 3 | 3 | |||||

| 4 | Special Issue on Disaster Risk Reduction and Sustainable Development | Sustainability | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 5 | Special Issue on Emergency Management Systems | International Journal of Intelligent Control and Systems | 9 | 9 | |||||

| Dissertation | |||||||||

| 1 | FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations | AISeL | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Total: | 8408 | 751 | 2499 | 1688 | 103 | 20 | 141 | ||

2.3. Extracting and synthesizing data

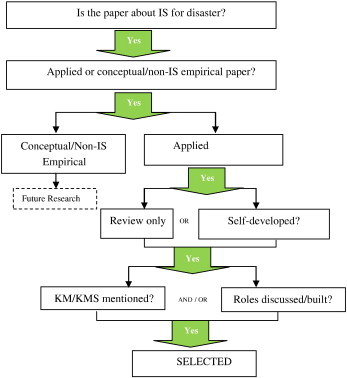

We extracted papers from the various sources mentioned above based on the following extraction process in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Extraction Process.

Fig. 2 recaps the basis of selecting papers for our review. As mentioned from the main databases and other options that were utilized, only KMS papers that were applied in nature and linked to emergency/disaster management were selected for further review. The subsection that follows presents a report of the papers that were relevant based on our selection criteria. From a total of 141 papers, only 51 were selected for final review.

3. Descriptive findings

3.1. Research Gap 1: KMS for disasters

3.1.1. Percentage of KMS for disaster/emergency papers over KM and KMS papers

Based on Table 3, and as further summarized in Table 4 , only 751 papers are KMS papers (9%), 103 papers are KMS for disaster papers (1%), and 20 papers for KMS for emergency (0.2%) from the total of 8408 KM papers. These percentages clearly highlight a lack of research in the area of KMS for disaster or emergency management.

Table 4.

Fraction of papers within KM and KMS total papers.

| KM Papers (Total = 8408) |

KMS Papers (Total = 751) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Units | % | % | |

| KMS + Disaster | 103 | 1% | 14% |

| KMS + Emergency | 20 | 0.2% | 3% |

| KMS | 751 | 9% | – |

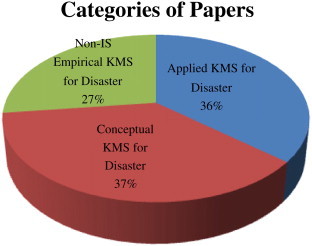

3.1.2. Percentage of applied-KMS for disaster/emergency papers over the total unit of analysis

Based on the inclusion conditions and the extraction process mentioned above, 141 papers were potential units of analysis. In this part, we further categorized the papers to indicate their respective types of studies. The number of units is indicated in the parentheses, and a pie chart is presented to reflect the percentages (Fig. 3 ):

-

a)

Applied-KMS for Disasters (51/36%): Research based on either the actual/real development of the KMS system or based on case(s) of KMS for disasters

-

b)

Conceptual KMS for Disasters (52/37%): Research based on pure conceptual papers that discuss the fundamental influences, processes, or components of KMS for disasters without any empirical test results

-

c)

Non-Applied Empirical KMS for Disaster (38/27%): Research based on evidence yield from non-IS or non-applied empirical such as surveys or interviews on KMS for disasters

Fig. 3.

Percentage of papers within the selected categories.

This paper will present an analysis of the 51 applied-KMS for disaster/emergency papers. We aim to highlight the research gaps in applied-KMS for disaster research and “roles” as an important component for emergency management information systems (EMIS). The 51 papers will be our final units of analysis.

3.1.3. Applied KMS-disaster papers: General information

Table 5 lists the 51 papers sampled for this paper. The information presented includes the following: if the authors of the 51 papers developed a system (1 = Yes, 0 = No), and vice-versa, the name of the EMIS, a brief description of the system, and emergency management focus and method used.

Table 5.

Summary of all papers of Applied-KMS for Disaster.

| No. | Ref. No. | Authors (Year) | System developed by Author | Name of the EMIS | Description | Emergency Management Focus | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [55] | Aedo et al. (2006) | 0 | ARCE | Web-emergency MIS | Web based system | Model based |

| 2 | [56] | Aziz et al. (2009) | 1 | RFID | Building assessment system | response and recovery | Scenario-based |

| 3 | [57] | Bas Linse et al. (2011) | 0 | iTask system | Workflow management systems | Search and Rescue | Case study |

| 4 | [58] | Ben Saoud et al. (2006) | 1 | SimGenis | Agentbased simulation | Rescue plans | Field test |

| 5 | [59] | Bharosa & Janssen (2010) | 1 | CEDRIC | Web-application for information sharing | Crisis response | Case study |

| 6 | [60] | Bond et al. (2008) | 1 | PPMS + RT | GPS Based Monitoring System | Prevention,Preparedness | Unclear |

| 7 | [61] | Büscher et al. (2009) | 1 | Overview | PalCom-enabled system | Virtual Teamwork | Experiment based |

| 8 | [62] | Campbell, B. (2011) | 1 | Virtual globe | Role playing games | Hospital Evacuation | Case study |

| 9 | [63] | Canós et al. (2011) | 1 | ShyWiki | Hypertext spatial media | Emergency Response | Case study |

| 10 | [64] | Caragea et al. (2011) | 1 | EMERSE | Emergency Response | Emergency Response | Experiment based |

| 11 | [65] | Catarci et al. (2011) | 1 | WORKPAD | Process Management System | Emergency Response | Lab test |

| 12 | [66] | Chen & Dahanayake (2009) | 1 | PMISRS | Personalized Multidisciplinary Information Seeking and Retrieval | Emergency Response | Service-Oriented |

| 13 | [67] | Chen, A. et al. (2011) | 1 | Integrated components | RFID tags over mobile devices | During disaster | Field test |

| 14 | [68] | Chiu et al. (2010) | 1 | DNRAS | Notification and Resource Allocation | Notification | Case study, Design |

| 15 | [69] | Dalal et al. (2011) | 1 | ExpertLens | Distribution group decision support | Communication | Delphi method |

| 16 | [70] | Danielsen & Chabada (2010) | 0 | Second Life™ | 3D multi user virtual environments | Evacuation, Training | Case study |

| 17 | [71] | Dilmaghani & Rao (2007) | 1 | RESCUE | Wireless Ad hoc mesh network | Communication | Field test |

| 18 | [72] | Fedorowicz & Gogan (2010) | 0 | BioSense | Detection tool for bio-terror attacks | Bio-terror surveillance | Case Study |

| 19 | [73] | Fernández et al. (2008) | 1 | vEOC using VRML97 | Collaborative multi-user | emergency response systems | Prototyping |

| 20 | [74] | French et al. (2009) | 0 | ThinkTank | GroupThinks | Collaboration | Experiment based |

| 21 | [75] | Fruhling et al. (2006) | 0 | STATPack | Support Distributed laboratories | Preparedness | Action research |

| 22 | [76] | Goulart, A. (2010) | 0 | Next Generation-9-1-1 | Real-world systems, spatial databases | Emergency call | Experiment based |

| 23 | [77] | Howe, A.W. (2011) | 0 | Social media | Collaboration system | Collaboration | Action Research |

| 24 | [78] | Kamill Panitzek et al. (2011) | 0 | MIT Roofnet | Access Points of Wireless Mesh | Communication | Case study |

| 25 | [79] | Majchrzak et al. (2011) | 1 | TN | Geographically enabled DSS | Traumatized Patients | Design Science |

| 26 | [80] | Marrella et al. (2011) | 1 | WORKPAD | Process Management System | Response | Lab test |

| 27 | [81] | McCarthy et al. (2008) | 1 | Expert Systems | Spartial DSS, Expert systems | Monitoring and Detection | Experiment based |

| 28 | [82] | McGuirl et al. (2009) | 1 | Imaging | UAV | Incident Command Center | Field test |

| 29 | [83] | Muhren et al. (2009) | 0 | MS Groove | A peer to peer software system | Humanitarian response | Case study |

| 30 | [19] | Murphy & Jennex (2006) | 0 | PeopleFinder, ShelterFinder | Emergency systems | Crisis Response | Case Study |

| 31 | [84] | Netten et al. (2006) | 0 | TAID | Task-Adaptive Information Distributor | Dynamic Collaborative | Experiment based |

| 32 | [85] | Plotnick et al. (2008) | 1 | Wiki | E-communication and collaboration | Response | Case study |

| 33 | [86] | Prasanna et al. (2011) | 1 | Prototype | Prototype for Situation Awareness | Fire Response | Prototyping |

| 34 | [87] | Raman et al. (2010) | 1 | TikiWiki | Wiki-based KMS | Emergency Response | Action research |

| 35 | [88] | Schoenharl et al. (2006) | 1 | WIPER | Wireless Phone-based | Emergency Response | Not clear |

| 36 | [89] | Shaluf & Ahamadun (2006) | 1 | TEES | Expert system using xCLIPS | Decision Support | Mixed Method |

| 37 | [90] | Smirnov, A. (2011) | 1 | DSS | Knowledge-based Intelligent DSS | Coordination | Case study |

| 38 | [91] | Stojmenovic et al. (2011) | 1 | Prototype | Decision Support Systems | Decision Support | Prototyping |

| 39 | [92] | Tatomir et al. (2006) | 1 | Prototype | Mobile AdHoc Network | Medical Coordination | Prototyping |

| 40 | [93] | Tecuci et al. (2007) | 1 | Disciple-VPT | A library of virtual planning experts | Training | Field test |

| 41 | [94] | Thomas et al. (2009) | 1 | EVResponse | GIS-based response management | Notification | Design science |

| 42 | [95] | Toomey et al. (2009) | 0 | Geospatial tools | Geospatial tools | Emergency Management | Action research |

| 43 | [96] | Trancoso et al. (2011) | 0 | OS | Integrated Operational System | Early warning system | Case study |

| 44 | [97] | Turoff et al. (1993) | 0 | EMISARI | Distributed group support systems | Decision Support | Case study |

| 45 | [12] | Turoff et al. (2004) | 1 | DERMIS | Emergency response system | Decision Support | Delphi method |

| 46 | [98] | Turoff et al. (2006) | 1 | CRISIS game | Computer Mediated Communication System | Emergency Preparedness | Field test |

| 47 | [99] | Wickler et al. (2011) | 1 | VCE | Virtual Collaboration Environment | Community Response | Experiment based |

| 48 | [100] | Wickler et al. (2006) | 1 | OpenCVE.net | Virtual Collaboration Environment | Collaboration | Experiment based |

| 49 | [101] | Xue & Liang (2004) | 0 | PHEIS | Public health emergency information system (PHEIS) in | Emergency Response | Case study |

| 50 | [102] | Yang et al., (2009) | 1 | SafetyNET | Short and long range wireless communication using sensor | Emergency Response | Experiment based |

| 51 | [103] | Yao et al. (2005) | 1 | Webboard | Virtual group decision | Emergency Preparedness | Case study |

Twenty-three of the total number of papers were from the United States, followed by the Netherlands and the UK with five papers each. Spain, Malaysia, Italy, and Denmark have two papers each. Table 6 summarizes the papers by country.

Table 6.

Source of Papers by Country.

| Country | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 23 | 45% |

| Netherlands | 5 | 10% |

| UK | 5 | 10% |

| Canada | 3 | 6% |

| Spain | 2 | 4% |

| Malaysia | 2 | 4% |

| Italy | 2 | 4% |

| Denmark | 2 | 4% |

| Portugal | 1 | 2% |

| Tunisia | 1 | 2% |

| Russia | 1 | 2% |

| Romania | 1 | 2% |

| Germany | 1 | 2% |

| Norway | 1 | 2% |

| Hong Kong | 1 | 2% |

| Total | 51 | 100% |

Most of the papers were published in the last decade (2000–2010). Only one paper was published in the 1990s (1993), as shown in Table 7 .

Table 7.

Source of Papers by Published Year.

| Years | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 16 | 31% |

| 2010 | 6 | 12% |

| 2009 | 9 | 18% |

| 2008 | 4 | 8% |

| 2007 | 2 | 4% |

| 2006 | 10 | 20% |

| 2005 | 1 | 2% |

| 2004 | 2 | 4% |

| 1993 | 1 | 2% |

| Total | 51 | 100% |

The 51 papers selected were from 12 journals/conferences/special issues. IJISCRAM (14 papers) is the main paper contributor followed by special issues (12), and ISCRAM and HICSS conference proceedings (8). The rest of the papers also came from highly ranked IS conference and journals such as TFSC, AMCIS, JITTA, MISQ, and DPM. Table 8 presents the sources of papers.

Table 8.

Source of Papers by Journal/Conference/Special issues.

| Source | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| IJISCRAM | 14 | 27% |

| Special issue (4 journal issues) | 12 | 24% |

| ISCRAM (Conf) | 8 | 16% |

| HICSS | 8 | 16% |

| JITTA | 4 | 8% |

| AMCIS | 2 | 4% |

| TFSC | 1 | 2% |

| DPM | 1 | 2% |

| MISQ | 1 | 2% |

| Total | 51 | 100% |

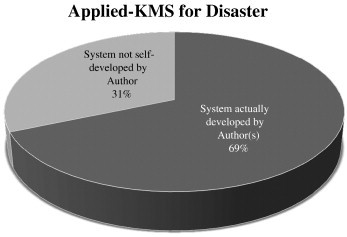

3.1.4. Categories of applied KM systems

Up to 35 papers (69%) (Fig. 4 ) are in the category of KM systems that the author(s) actually developed, and the remaining 16 papers (31%) elaborate actual systems for disasters based on organizational cases or review of publicly available KMS tools.

Fig. 4.

Categories of applied KM systems.

3.1.5. Explicit indication of KMS concept

Only 20 papers from the 51 papers had actually mentioned KM or the KMS concept explicitly. The rest of the papers did not mention KM or KMS, although the type of IS that they have referred to is categorized within KMS tools (Table 9 ).

Table 9.

Explicit indication of KMS concept in the applied-KMS for disaster papers.

| Units | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicated KMS Concept explicitly | Yes | 19 | 37% |

| No | 32 | 63% | |

| Total | 51 | 100% | |

3.1.6. KMS tools used for the applied-KMS for disaster research

Literature indicates that various technological tools can be used to enable KM processes. We summarized and synchronized KMS tools enlisted by three papers in KMS. [104] enlisted 12 tools for KMS, [30] with 8 tools, and [105] with 7 tools. A KMS can be a single tool or a combination of many tools to facilitate KM processes [104]. All these tools are listed in Table 8 with an additional number of tools collected based on the 51 papers (Table 10 ).

Table 10.

KMS tools.

| Gupta & Sharma (2003) [104,p.18] | Alavi & Liedner (2001) [30] | Liao (2003) [105] |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Expert systems 2. Distributed hypertext systems 3. Document management 4. Geographic information systems (GIS) 5. Help desk technology 6. Intranets 7. Concept mapping 8. Semantic networks 9. Hypertext (an expanded semantic network) 10. Information modeling 11. Contextual indexes 12. Metadata |

1. Browser 2. E-mail 3. Search/retrieval tools 4. Information repositories 5. Web server 6. Agents/filters 7. External server services 8. Videoconferencing |

1. KM Framework 2. Knowledge-based systems (KBS) 3. Data mining 4. Information and communication technology (ICT) 5. Artificial intelligence (AI)/Expert systems 6. Database technology 7. Modeling |

We summarized all the above tools into 16 KMS common tools based on the 51 papers. The following are the counts of applied-KMS for disaster papers by the KMS tools. Table 11 maps the tools that authors used/mentioned in the samples selected.

Table 11.

Plot of KMS tools used by authors.

| KMS Tools |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors (year) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 (NC) | |

| 1 | Aedo et al. (2006) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Aziz et al. (2009) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Bas et al. (2011) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Ben Saoud et al. (2006) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Bharosa & Janssen (2010) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Bond et al. (2008) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Büscher et al. (2009) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Campbell, B. (2011) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Canós et al. (2011) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Caragea et al. (2011) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 11 | Catarci et al. (2011) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Chen & Dahanayake (2009) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Chen, A. (2011) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Chiu et al. (2010) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 15 | Dalal et al. (2011) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 16 | Danielsen & Chabada (2010) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 17 | Dilmaghani & Rao (2007) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 18 | Fedorowicz & Gogan (2010) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 19 | Fernández et al. (2008) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 20 | French et al. (2009) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 21 | Fruhling et al. (2006) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 22 | Goulart, A. (2010) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 23 | Howe, A.W. (2011) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 24 | Kamill et al. (2011) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 25 | Majchrzak et al. (2011) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 26 | Marrella et al. (2011) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 27 | McCarthy et al. (2008) | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| 28 | McGuirl et al. (2009) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 29 | Muhren et al. (2009) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 30 | Murphy & Jennex (2006) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 31 | Netten et al. (2006) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 32 | Plotnick et al. (2008) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 33 | Prasanna et al. (2011) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 34 | Raman et al. (2010) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 35 | Schoenharl et al. (2006) | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| 36 | Shaluf & Ahamadun (2006) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 37 | Smirnov, A. (2011) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 38 | Stojmenovic et al. (2011) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 39 | Tatomir et al. (2006) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 40 | Tecuci et al. (2007) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 41 | Thomas et al. (2009) | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| 42 | Toomey et al. (2009) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 43 | Trancoso et al. (2011) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 44 | Turoff et al. (1993) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 45 | Turoff et al. (2004) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 46 | Turoff et al. (2006) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 47 | Wickler et al. (2011) | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| 48 | Wickler et al. (2006) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 49 | Xue & Liang (2004) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 50 | Yang et al., (2009) | X | |||||||||||||||||

| 51 | Yao et al. (2005) | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 3 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 11 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 2 | |

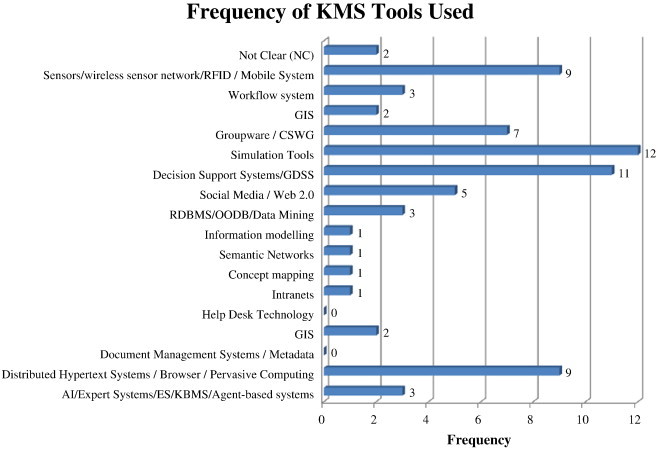

Table 12 and Fig. 5 present the frequency of a particular tool that falls within the KMS classification used by authors in reporting their work.

Table 12.

Frequency and percentage of KMS tools used by authors.

| No | KMS Tools | Counts | Percentage from total (51 papers) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AI/Expert Systems/ES/KBMS/Agent-based systems | 3 | 6% |

| 2 | Distributed Hypertext Systems/Browser/Pervasive Computing | 9 | 18% |

| 3 | Document Management Systems/Metadata | 0 | 0% |

| 4 | GIS | 2 | 4% |

| 5 | Help Desk Technology | 0 | 0% |

| 6 | Intranets | 1 | 2% |

| 7 | Concept mapping | 1 | 2% |

| 8 | Semantic Networks | 1 | 2% |

| 9 | Information modeling | 1 | 2% |

| 10 | RDBMS/OODB/Data Mining | 3 | 6% |

| 11 | Social Media/Web 2.0 | 5 | 10% |

| 12 | Decision Support Systems/GDSS | 11 | 22% |

| 13 | Simulation Tools | 12 | 24% |

| 14 | Groupware/CSWG | 7 | 14% |

| 15 | GIS | 2 | 4% |

| 16 | Workflow system | 3 | 6% |

| 17 | Sensors/wireless sensor network/RFID/Mobile System | 9 | 18% |

| 18 | Not Clear (NC) | 2 | 4% |

Fig. 5.

KMS tools used by authors.

Simulation tools seem to be popular for KMS for disasters. Authors from 12 papers (24%) have tested their propositions using simulation tools. This is followed by DSS (10 papers), distributed hypertext systems/browser/pervasive computing (8 papers), and sensors/wireless sensor network/RFID/mobile system tools (8 papers).

3.1.7. Applied-KMS for disaster papers by KM dimensions

The papers were categorized based on the three major dimensions of KM papers of [13], namely, KM influences, KM activities, and KM resources [106]. The papers categorized as KM influences examined the success factors and KM implementation outcomes. The papers categorized as KM activities discussed KM processes, such as knowledge creation, acquisition, sharing, evolution, and knowledge transfer. Papers grouped as KM resources expounded on the KM components. We have added one more dimension called Knowledge-base, as many applied-KMS for disaster papers constantly indicated this component. Table 13 shows the plots of each paper by the KM dimensions.

Table 13.

KM dimensions.

| No. | Authors (Year) | Description of the System | KM Categories based on Holsaple & Joshi (2004) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KM Resources | KM Influences | KM Processes |

Knowledge-base | |||||||

| Knowledge Creation | Knowledge Acquistion | Knowledge Sharing | Knowledge Evolution | Knowledge Transfer | ||||||

| 1 | Smirnov, A. (2011) | Knowledge-based Intelligent DSS | X | X | ||||||

| 2 | Fruhling et al. (2006) | Support Distributed laboratories | X | |||||||

| 3 | Caragea et al. (2011) | Enhanced Messaging for the Emergency Response Sector | X | X | ||||||

| 4 | Chiu et al. (2010) | Notification and Resource Allocation | X | |||||||

| 5 | Tecuci et al. (2007) | A library of virtual planning experts | X | |||||||

| 6 | Shaluf & Ahamadun (2006) | Expert system using xCLIPS | X | X | X | |||||

| 7 | Fernández et al. (2008) | Collaborative multi-user online app | X | |||||||

| 8 | Fedorowicz & Gogan (2010) | Detection tool for bio-terror attacks | X | |||||||

| 9 | Canós et al. (2011) | Hypertext spatial media | X | |||||||

| 10 | Yang et al., (2009) | Short and long range wireless communication using sensor network | X | X | ||||||

| 11 | Thomas et al. (2009) | GIS-based response management | X | X | ||||||

| 12 | Raman et al. (2010) | Wiki-based KMS | X | X | ||||||

| 13 | Turoff et al. (2004) | Emergency response system | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| 14 | Turoff et al. (2006) Computer Mediated Communication System | |||||||||

| 15 | Bharosa & Janssen (2010) | Web-application for information sharing | X | X | X | X | ||||

| 16 | Murphy & Jennex (2006) | Emergency systems | X | X | ||||||

| 17 | Wickler et al. (2006) | Virtual Collaboration Environment | X | |||||||

| 18 | Xue & Liang (2004) | Public health emergency information system (PHEIS) in China | X | |||||||

| 19 | Muhren et al. (2009) | Peer to peer software system:MS Groove | X | X | X | |||||

| Frequency | 8 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 6 | ||

4. Utilizing the findings to inform research and practice

Based on our extensive and systematic review of the literature pertaining to KM/KMS and disaster management, we highlight two major gaps that we believe warrant the attention of the research community. These two areas are (i) EMIS-KMS definition, use, and methods, and (ii) embedding roles in the KM systems developed.

4.1. EMIS–KMS definition, use, and methods

Our review of the 51 papers suggests the following. A number of researchers do not necessarily mention the term KM or KMS in the context of working with (design/implementation/assessment) of EMIS in relation to disaster management. In this regard, we call for a closer alignment between EMIS and KMS, given that at times, the objectives of both EMIS- and KMS-driven systems are similar in the area of supporting disaster/emergency management. In terms of use, the papers focused on emergency response and rescue (Table 5). Another popular use is for decision support. Very few papers describe EMIS-KMS use for pre-disaster stages, such as training, preparedness, mitigation, and prevention. We also find that although the majority of the authors have conducted an exploratory and experimental case study method, a limitation exists on action research that aims to solve real problems by introducing change into the social setting (Table 14 ). Hence, more work can be done in this area.

Table 14.

Methods used.

| No. | Methods Used | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Model based | 1 | 2% |

| 2 | Scenario-based | 1 | 2% |

| 3 | Case study | 13 | 25% |

| 4 | Field test | 6 | 12% |

| 5 | Unclear | 1 | 2% |

| 6 | Experiment based | 9 | 18% |

| 7 | Lab test | 2 | 4% |

| 8 | Service-Oriented | 1 | 2% |

| 9 | Field trials | 6 | 12% |

| 10 | Delphi method | 2 | 4% |

| 11 | Prototyping | 3 | 6% |

| 12 | Action research | 4 | 8% |

| 13 | Design Science | 1 | 2% |

| 14 | Mixed Method | 1 | 2% |

| Total | 51 | 100% | |

In the disaster context, access is needed for a wide range of real-time information and knowledge that requires coordination. Therefore, knowledge management systems can play a pivotal role in enhancing disaster efforts that allow more use of data and faster actions.

4.2. Roles in knowledge bases for dynamic emergency management

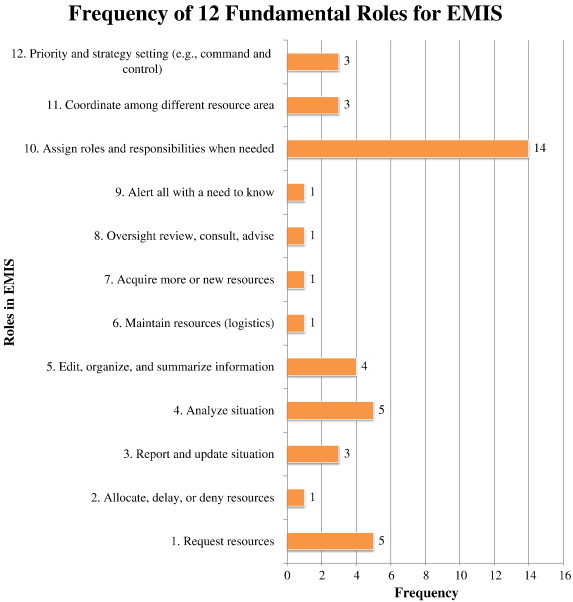

This section aims to examine how the concept of roles is built into the applied-KMS for disasters and supported by tools to perform human roles. We scrutinized the 51 papers to determine if the authors have somehow built in the concept of human roles within their systems. From the 51 papers, only 22 papers relate the system developed/analyzed to any one or more roles that humans play in using these systems. [12, p. 15] outlined 12 fundamental roles for EMIS. We examined if one or more of these roles are built in the EMIS/KMS. Fig. 6 gives the details of the number of papers that include “roles” for EMIS design.

Fig. 6.

Overall number of papers that includes ‘Roles’ for EMIS design in Applied-KMS for Disaster.

We then plotted the roles that the papers indicated based on the 12 fundamental roles outlined by [12], as shown in Table 15 . The plot chart clearly suggests that more work can be done to map systems design to support the 12 fundamental roles as called for by [12]. Thus, a scope for more research in this area is also present.

Table 15.

Plot of 22 Applied-KMS for disaster papers that indicated any of the 12 Fundamental roles.

| 12 Fundamental roles in EM (Turoff et al., 2004, pg. 15–17) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

||

| No | Authors | Request resources: People & Things | Allocate, delay, or deny resources | Report and update situation | Analyze situation | Edit, organize, and summarize information | Maintain resources (logistics) | Acquire more or new resources | Oversight review, consult, advise | Alert all with a need to know | Assign roles and responsibilities when needed | Coordinate among different resource area | Priority and strategy setting (e.g., command and control) |

| 1 | Smirnov, A. (2011) | X | X | ||||||||||

| 2 | Fruhling et al. (2006) | X | |||||||||||

| 3 | Howe, A.W. (2011) | X | |||||||||||

| 4 | Campbell, B. (2011) | X | |||||||||||

| 5 | Caragea et al. (2011) | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 6 | Chiu et al. (2010) | X | |||||||||||

| 7 | Aedo et al. (2006) | X | X | ||||||||||

| 8 | Shaluf & Ahamadun (2006) | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 9 | Fernández et al. (2008) | X | |||||||||||

| 10 | Fedorowicz & Gogan (2010) | X | |||||||||||

| 11 | Yang et al., (2009) | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 12 | Plotnick et al. (2008) | X | |||||||||||

| 13 | Marrella et al. (2011) | X | |||||||||||

| 14 | Turoff et al. (2004) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 15 | Ben Saoud et al. (2006) | X | |||||||||||

| 16 | Netten et al. (2006) | X | |||||||||||

| 17 | Bharosa & Janssen (2010) | X | |||||||||||

| 18 | Chen & Dahanayake (2009) | X | X | ||||||||||

| 19 | Prasanna et al. (2011) | X | |||||||||||

| 20 | Majchrzak et al. (2011) | X | |||||||||||

| 21 | Murphy & Jennex (2006) | X | |||||||||||

| 22 | Muhren et al. (2009) | X | |||||||||||

5. Future research

Researchers involved in examining the relationship between knowledge-based EMIS and emergency management could consider the main findings of the current study to explore the options for future work. The four major themes for future research consideration include:

-

•

Theme 1: Use of terminology

-

•

Theme 2: Applied knowledge-based EMIS in actual disaster situations

-

•

Theme 3: Extended action research in the context of EMIS and disaster management

-

•

Theme 4: Empirical investigation on successful EMIS implementation and use in support of emergency management from the perspectives of both the community (local citizens) and emergency planners/responders.

5.1. Theme 1: Use of terminology

Our study shows that researchers seem to interchangeably use various terms such as emergency management, crisis management, and disaster management. Therefore, we call for researchers to streamline the use of terminologies pertaining to emergency/disaster management, as these terms may neither necessarily reflect similar ideas nor could offer different connotations in different circumstances. A need also exists for researchers to clearly differentiate between EMIS and KMS in aid of emergency management. A knowledge management system refers to any IT-based system that is “developed to support and enhance the organizational knowledge processes of knowledge creation, storage, retrieval, transfer, and application” [30, p. 114]. The definition includes various tools described in the earlier sections of the current paper. In this context, the following questions suggest the need for more research: (i) Is there a difference between EMIS and KMS for emergencies? (ii) Do these systems differ based on objectives, functions, and features used in the context of emergency management? (iii) Could different forms of knowledge-based EMIS systems be more relevant for a particular disaster phase?

5.2. Theme 2: Applied knowledge-based EMIS in actual disaster situations

Systems that are well developed and tested in laboratory conditions/simulators but not applied to the real world may seem pointless. More work is also needed in the area of applying KM technologies and systems to actual disasters. This undertaking would require significant efforts and approval from relevant authorities. Nevertheless, findings from such studies would improve disaster response and management. Researchers could continue working with KM systems and conduct tests during actual drills that replicate natural/man-made disasters. We would call for more work on the application of KMS to map the system objectives, functionality, and design to the different phases of a disaster situation. This aspect also applies to mapping the system design to the 3Cs (communication, coordination, and collaboration) in a disaster.

5.3. Theme 3: Extended action research in the context of EMIS and emergency management

Under Theme 3, more research focusing on the use of applied research methodology such as action research will help researchers understand the relevance of EMIS in emergency management. Action research is gaining popularity, particularly within the IS community. Researchers can use the problem-solving nature of action research to better understand issues inherent in the overall communication, coordination, information sharing, and dissemination across the different phases of a disaster.

5.4. Theme 4: Successful knowledge-based EMIS implementation

Emergency management efforts require timely interaction and communication of correct information, and applying relevant knowledge to save lives and property. This concept calls for a KMS that can support and sustain data, and allow efficient and effective information and knowledge processes at a very crucial point. IS in the form of knowledge management systems can support timely interactions and communication in disaster management. The integration of knowledge management concepts into a disaster management system is still very limited. Hence, identifying and testing the success factors for using knowledge-based systems in emergency management is timely. Success factors can be examined from the stakeholder viewpoint of the following groups involved in or impacted by disasters: local authorities, federal agencies, local communities, emergency responders, planners, social worker groups, and non-government organizations. In this scope of work, researchers can use either a deductive or inductive approach to examine KM success factors in the disaster management context.

6. Discussion and summary observations

Our discussions on the use of KMS in aid of disaster management imply the following. Firstly a well-designed KMS can bring a group of experts together—thus offering a powerful platform for sharing prior experience in managing disasters. This knowledge base can in turn be used to aid timely response disaster situations. Although the idea of using a KMS to aid disaster management has attracted some interest in the last decade, the ideas inherent in applying expert knowledge to aid disaster planning and response are arguably not new. [108] introduced the notion of using Delphi, more than three decades ago and suggested the importance of expert viewpoints being brought together to address disaster management issues. The major difference though between this seminal work and contemporary literature/projects on KMS is that while the former systems were predominantly led by structured-military style of disaster management driven by manual procedures, the latter systems can be designed to offer more robust and flexible creation, storage, sharing and ultimately dissemination of a disaster related knowledge base. Secondly, even within the realm of a KMS to support disaster management efforts, literature suggests that these systems can benefit from the utilization of social networking ideas—driven by web 2.0 (and beyond) architectures, to offer a more dynamic and real time use of KMS in an actual disaster situation [12], [54], [77], [109], [110].

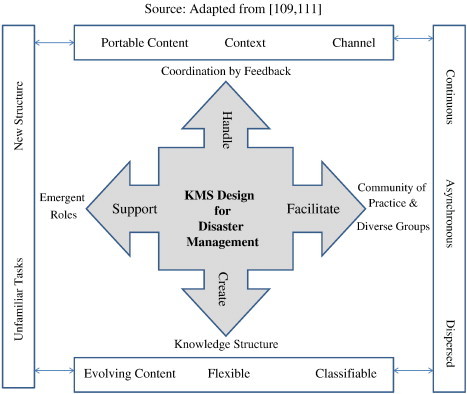

Fig. 7 further explains some of our findings based on our assessment of the literature, which can also be used to suggest several core differences between an informational ‘vis a vis’ knowledge view of systems designed to support disaster management.

Fig. 7.

KMS Design Decisions for Disaster Management.

Researchers working on KMS design to support disaster management should take the following issues into consideration. The KMS design should be designed to:

-

•

Facilitate community of practice and cater for the need of diverse stakeholder groups impacted by a particular disaster situation (i.e. going beyond mere structured documentation of structured and organized data) [109]

-

•

Allow the creation of an evolving knowledge structure—again implying that while the emphasis of an emergency management information system is largely on the collection of useful information pertaining to disasters, a well-designed KMS caters to the ability of individuals and groups to continuously make changes to the disaster knowledge base seamlessly [109], [111]. [109] in this regard assert that any knowledge structure should support the nature of an ever evolving context, allow flexible alterations and thus classification of meaning in relation to disasters. The authors further add that modern technologies such as wikis, blogs, and other forms of Web 2.0 and beyond architectures support these requirements [109].

-

•

Support both informational and knowledge requirements of different roles played by emergency planners and responders (i.e. allow communities to share both tacit and explicit knowledge domains pertaining to disasters that are highly contextual) [12], [111].

-

•

Handle timely coordination efforts through both synchronous and asynchronous feedback, during the different phases of a disaster situation. In this regard, we propose that an Emergency Management Information System supports mainly structural/organizational requirements in managing disasters. However a KMS is driven by the need to support timely interactions between humans (communities of practice), and support continuously conversations (synchronous/asynchronous) between people involved in disaster management [109].

7. Conclusion

This study aims to inform the disaster/emergency knowledge community about the research gaps in the application of knowledge-driven systems in support of emergency management that have been published in the last two decades. In this study, we applied the five-stage methodology of [52] in writing papers based on the comprehensive review of literature in a given area. This methodology was used to understand the extent and nature of applied KMS research in aid of emergency/disaster management. From an extensive search of 8408 papers in the KM domain, our search list was narrowed to 51 papers (0.6%) that have examined applied-KMS for disaster/emergency. Our in-depth review of the 51 papers suggests that a scope for more significant research on the four major areas is present. First, an urgent need exists for researchers to streamline the use of terminologies pertaining to emergency/disaster management. Second, we feel that more work can be done to ascertain if KMS (for emergency management) and EMIS share similar goals or otherwise. The extent of the similarities/differences between KMS-EMIS in this context could also be further explored. Third, only three papers clearly use an action research approach and relate KMS to disaster/emergency management, despite the call for IS researchers to conduct more applied work based on action research methodology [107]. Finally, more empirical work is required to better understand the determinants of KMS success factors in the context of emergency/disaster management.

Biographies

Magiswary Dorasamy is a senior lecturer and the chair for Centre of Excellence in Knowledge and Innovation Management (CEKIM) in Faculty of Management, Multimedia University Malaysia. Her area of expertise is Information Systems for disaster. To date, she has had a distinguished corporate career in ICT industries and academia career spanning over 17 years and has established herself with extensive experience in consultancy, research and development. Her PhD research is on information systems in the form of Knowledge Management Systems for disaster planning and response using an action research approach.

Murali Raman received his PhD in MIS from the School of IS & IT, Claremont Graduate University, USA. He is a Rhodes Scholar and a Fulbright Fellow. His other academic qualifications include an MBA from Imperial College of Science Technology and Medicine, London, an MSc in HRM from London School of Economics. Dr. Raman is currently a Professor attached to Graduate School of Management, Multimedia University Malaysia.

Maniam Kaliannan received his PhD in e-Government from the School of Economics, University Malaya, Malaysia. He has served both as lecturer and trainer for the past 20 years. He has conducted various corporate and government training programs for both middle level and senior management teams. On the academic front, he has published his work in both national and international journals and conferences. Dr. Maniam is currently an Associate Professor attached to School of Business, The Nottingham University of Malaysia.

Contributor Information

Magiswary Dorasamy, Email: magiswary.dorasamy@mmu.edu.my.

Murali Raman, Email: murali.raman@mmu.edu.my.

Maniam Kaliannan, Email: maniam.kaliannan@nottingham.edu.my.

References

- 1.UN/ISDR . UN/ISDR; Geneva: 2004. Living with Risk: A Global Review of Disaster Risk Reduction Initiatives. (Retrieved on December 28, 2010, from http://www.unisdr.org) [Google Scholar]

- 2.McEntire D.A. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; NJ: 2007. Disaster Response and Recovery. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson K. Proceedings of the 39th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii, USA. 2006. Examining factors associated with IT disaster preparedness. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller D. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, London: 2004. Exposing The Errors: An Examination of The Nature of Organizational Crisis, in Responding to Crisis: A Rhetorical Approach to Crisis Communication. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asghar S., Alahakoon D., Churilov L. Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Hybrid Intelligent Systems (HIS'04), Hawaii, USA. 2004. A hybrid decision support system model for disaster management. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao L., Zhou G. Proceedings in 2008 ISECS International Colloquium in Computing, Communication, Control and Management. IEEE Computer Society; 2008. Research on emergency response mechanisms for meteorological disasters. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee J., Bui T. Proceedings of the 33rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii, USA. 2000. A template-based methodology for disaster management information systems; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ki-Moon B. 2011. UN General Assembly: Invest in Natural Disaster Risk Reduction. (Retrieved on 6 October, 2011, from http://www.ensnewswire.com/ens/feb2011/2011-02-10-01.html) [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNDP . United Nation Development Programme. 2011. Preventing crisis, enabling recovery: 2010 Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munich R.E. Munchener Ruckversicherungs-Gesellschaft; Munchen, Germany: 2011. Natural Catastrophes 2010 Analyses, Assessments, Positions. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lansley D., Donaldson K. UN/ISDR; Victoria, Australia: 2009. Reduce Risk and Raise Resilience. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turoff M., Chumer M., Walle B.V.D., Yao X. The design of a dynamic emergency response management information system (DERMIS) J. Inform. Technol. Theory Appl. 2004;5(4):1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turoff M. Delphi conferencing: computer based conferencing with anonymity. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1972;3(2):159–204. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jennex M.E. Proceedings the Tenth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New York. 2004. Emergency response systems: lessons from utilities and Y2K; pp. 2148–2155. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarvodaya.org 2011. www.sarvodaya.org Sri Lanka. Retrieved on July 2, 2011 from.

- 16.Sahana Disaster Management Systems 2011. http://www.sahana.lk/image/tid/3 Sri Lanka. Retrieved on July 2, 2011 from.

- 17.Iakovou E., Douligeris C. An information management system for the emergency management of hurricane disasters. Int. J. Risk Assess. Manage. 2001;2(3/4):243–262. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitamato A. Proceeding of the 4th International Symposium on Digital Earth. 2005. Digital typhoon: near real-time aggregation, recombination and delivery of typhoon-related information. (Retrieved October 26, 2011 from http://www.cse.iitb.ac.in/~neela/MTP/Stage1-Report.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy T., Jennex M.E. Knowledge management, emergency response, and Hurricane Katrina. Int. J. Intell. Contr. Syst. 2006;11(4):199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wattegama C. United Nations Development Programme—Asia-Pacific Development Information Programme (UNDP-APDIP) and Asian and Pacific Training Centre for Information and Communication Technology for Development (APCICT), Bangkok. 2007. ICT for disaster management. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devadoss P.R., Pan S.L., Singh S. Managing knowledge integration in a national health-care crisis: lessons learned from combating SARS in Singapore. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2005;9(2):266–275. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2005.847160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leidner D., Pan G., Pan S.L. The role of IT in crisis response: lessons from the SARS and Asian Tsunami disasters. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2009;18:80–99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Incident Management Systems, USA 2012. http://www.fema.gov/national-incident-management-system Retrieved on October 20, 2012 from.

- 24.LA RED . Report for UNDP-ISDR. 2003. Comparative analysis of disaster database EmDat-DesInventar. (Retrieved on January 20, 2011, from www.desenredando.org) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marulanda M.C., Cardona O.D., Barbat A.H. Revealing the socioeconomic impact of small disasters in Colombia using the DesInventar database. Disasters. 2010;34(2):552–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DesInventar System www.desinventar.org/en/file/73/view/73 Retrieved on December 2, 2010, from.

- 27.Dorasamy M., Raman M. Proceedings the 8th International Information System for Crisis Response and Management (ISCRAM) Conference, Lisbon, Portugal. 2011. Information systems to support disaster planning and response: problem diagnosis and research gap analysis; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 28.King W.R. Knowledge management: a systems perspective. Int. J. Bus. Syst. Res. 2007;1(1):5–28. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nonaka I., Takeuchi H. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. The Knowledge-creating Company. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alavi M., Leidner D.E. Review: knowledge management and knowledge management systems: conceptual foundations and research issue. MIS Q. 2001;25(1):107–136. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank U. Thomson Learning; London, UK: 2002. A Multi-layer Architecture for Knowledge Management Systems. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turban E., McLean E., Wetherbe J., Leidner D. 6th ed. John Wiley & Sons; New Jersey: 2008. Information Technology for Management. [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Brien C., Hanka R., Buchan I., Heathfield H. In: Managing Information Overload in the Health Sector: The WaX Active Library System. Barnes S., editor. Thomson Learning; Oxford: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta J.N.D., Sharma S.K. IDEA Group Publishing; Hershey, USA: 2004. Creating Knowledge Based Organizations. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holsapple C.W., Whinston A.B. Course Technology. EUA; Cambridge: 1996. Decision support systems: a knowledge-based approach. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alavi M., Joachimsthaler E. Revisiting DSS implementation research: a meta-analysis of the literature and suggestion for researchers. MIS Q. 1992;16(1):95–116. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stenmark D., Lindgren R. Knowledge management systems: towards a theory of integrated support. In: Jennex M., editor. Information Science Reference. Hershey; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finnegan P., Sammon D. In: Fundamentals of Implementing Data Warehousing in Organizations. Stuart B., editor. Thomson Learning; Oxford: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turoff M. Past and future emergency response information systems. Commun. ACM. 2002;45(4):29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turoff M., Plotnick L., White C., Hiltz S.R. Proceedings of the 5th International ISCRAM Conference, Washington, DC, USA. 2008. Dynamic emergency response management for large scale decision making in extreme events. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kostman J.T. 20 rules for effective communication in a crisis. Disaster Recov. J. 2004;17(2):20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Kirk M. Collaboration in BCP skill development. Disaster Recov. J. 2004;17:20. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tiwana A. Prentice Hall; United States: 2000. The Knowledge Management Toolkit. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davenport H.T., Prusak L. Harvard Business School Press; Boston, MA: 1998. Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burnell L., Priest J., Durrett J. Developing and maintaining knowledge management system for dynamic, complex domains. In: Gupta J., Sharma S., editors. Creating Knowledge Based Organizations. IGP; London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jennex M.E. What is KM? Int. J. Knowl. Manage. 2005;1(4):i-iv. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harrald J.R. Agility and discipline: critical success factors for disaster response. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2011;604(1):256–272. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Comfort L.K. Cities at risk: Hurricane Katrina and the drowning of New Orleans. Urban Aff. Rev. 2006;46(4):501–516. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Little R.G., Birkland T.A., Wallace W.A., Herabat P. Proceedings of the 40th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Hawaii, USA. 2007. Socio-technological systems integration to support tsunami warning and evacuation. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horan J., Ritchie L.A., Meinhold S., Gill D.A., Houghton B.F., Gregg C.E. Evaluating disaster education: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's TsunamiReady™ community program and risk awareness education efforts in New Hanover County, North Carolina. In: Ritchie L.A., MacDonald W., editors. Enhancing Disaster and Emergency Preparedness, Response, and Recovery Through Evaluation: New Directions for Evaluation. Wiley/Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2010. pp. 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Samarajiva, Rohan K.J., Malathy S.A., Peter Z., Ayesha . Paper for the Design of an effective all-hazard public warning system,Version 2.1, LIRNEasia. 2005. National early warning system: Sri Lanka—a participatory concept. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tranfield D., Denyer D., Smart P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003;14:207–222. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alavi M., Leidner D.E. Knowledge management systems: issues, challenges, and benefits. Commun. AIS. 1999;1(7):1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raman M., Ryan T., Olfman L. Proceedings of the 39th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. 2006. Knowledge management system for emergency preparedness: an action research study. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aedo I., Díaz P., Sanz D. An RBAC model-based approach to specify the access policies of Web-based emergency information systems. Int. J. Intell. Contr. Syst. 2006;11(4):272–283. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aziz Z., Peña-Mora F., Chen A., Lantz T. Supporting urban emergency response and recovery using RFID-based building assessment. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2011;18(1):35–48. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lijnse B., Nanne R., Jansen J.M., Plasmeijer R. Proceedings of the 8th International ISCRAM Conference Lisbon, Portugal. 2011. Capturing the Netherlands Coast Guard's SAR workflow with iTasks. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saoud N.B.B., Mena T.B., Dugdale J., Pavard B., Ahmed M.B. Assessing large scale emergency rescue plans: an agent based approach. Int. J. Intell. Contr. Syst. 2006;11(4):260–271. [Google Scholar]