Abstract

In this paper, an improved recovery method for target ssDNA using amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles (ASMNPs) is reported. This method takes advantages of the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles prepared using water-in-oil microemulsion technique, which employs amino-modified silica as the shell and iron oxide as the core of the magnetic nanoparticles. The nanoparticles have a silica surface with amino groups and can be conjugated with any desired bio-molecules through many existing amino group chemistry. In this research, a linear DNA probe was immobilized onto nanoparticles through streptavidin conjugation using covalent bonds. A target ssDNA(I) (5′-TMR-CGCATAGGGCCTCGTGATAC-3′) has been successfully recovered from a crude sample under a magnet field through their special recognition and hybridization. A designed ssDNA fragment of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus at a much lower concentration than the target ssDNA(I) was also recovered with high efficiency and good selectivity.

Keywords: DNA recovery, Amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles, Sever acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

1. Introduction

The separation and recovery of an analyte is a fundamental technique in many fields, including chemistry, biology, biomedicine, industry, and environmental control. Target DNA separation and recovery is important for numerous applications in biotechnology and medicine. These applications include gene transfection, accurate PCR for mutation detection, gene therapy, species identification, and evolutionary analysis [1]. There are two principles for recovery of target DNA. Gel electrophoresis is a traditional method of DNA separation and recovery [2], [3], [4], in which a strand is cut into many pieces and passed through a porous gel, wherein shorter pieces move faster and farther than the longer ones. From the distribution of the fragments, information about the genetic content can be determined through comparison with the marker DNA. To recover the wanted target DNA, the further extremely time-consuming experiments must be performed, including recovery of DNA from agarose by electroelution, recovery of DNA from agarose gels with spin column, recovery of DNA from agarose gels by phenol extraction, and recovery of DNA from low-melting agarose with LiCl [5]. On the other side, the recovery of trace target nucleic acids in complex chemical and genetic backgrounds (e.g. pathogen detection) can also be realized based on the nucleic acid or peptide nucleic acid affinity-purification methods [6], [7]. However, these experimental methods possess a typical run time of more than 10 h due to the complex separation steps, such as centrifugation, columniation, filtration, and so on.

In recent years, the integration of nanotechnology with biology and medicine has utilized functionalized nanoparticles in molecular diagnostics, therapeutics, molecular biology, bioengineering, and bio-separation [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. All kinds of functionalized nanoparticles have been developed; in particular, substantial progress has been made in magnetic nanospheres and ferrofluids development technologies [18], [19]. Due to their size-dependent properties and dimensional similarities to biomacromolecules [20], [21], [22], these magnetic nanoparticles can be used as contrast agents for in vivo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [23], [24], as long-circulating carriers for drug release/delivery, and potentially as oligonucleotide separation devices in medicine and biotechnology. Magnetic isolation of these bio-molecules is faster than standard liquid chromatography and electrophoresis techniques. Target molecules, such as peptides, proteins, and oligonucleotides can be separated and recovered from untreated crude samples without any filtration, and pretreatment steps by magnetic bio-conjugates, i.e. by attaching bio-specific ligands to them. Tan and co-workers developed a novel genomagnetic nanocapture for the collection of trace amounts of DNA/mRNA molecules based on the molecular beacon [25]. In fact, this novel nanocapture is a kind of magnetic nanoparticle, which incorporates DNA probes. A weakness of this protocol is that DNA probe immobilization was carried out through conjugation of avidin onto the nanoparticles by use of a weak electrostatic interaction. Such linking is not stable, which will affect the lifetime of the nanocapture. At the same time, Tan et al. reported the collection of DNA using a molecular beacon (MBs) probe that is a class of DNA probes widely used in chemistry, biology, biotechnology and medical sciences for bio-molecular recognition. However, in most biosensor applications, the sensitivity of the MBs immobilized on a silica surface is usually low due to its steric hindrance on the solid surface [26]. In addition, the sensitivity of the DNA probe will directly affect the efficiency of the separation and recovery. As known, the lifetime and the efficiency of separation and recovery are two important factors to the nanocapture.

In this paper, we reported an improved method for recovery of target ssDNA using amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles (ASMNPs). The amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles were prepared through the controlled synchronous hydrolysis of tetraethoxysilane and N-(β-amimoethyl)-γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane in a water nanodroplet using water-in-oil microemulsion, and employed iron oxide as the core of the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles. In this protocol, the DNA probe was immobilized onto nanoparticles through streptavidin conjugation using covalent bonds. Such linking is much more stable than electrostatic interaction. Moreover, we selected a linear DNA probe as a capture ssDNA, which is better than MBs in this method due in part to its ease of design, less steric hindrance, and high immobilization efficiency on the silica surface. A target ssDNA(I) (5′-TMR-CGCATAGGGCCTCGTGATAC-3′) was successfully recovered by using this protocol. This method has also been used successfully to recover trace concentrations of target ssDNA fragment of sever acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) virus with high efficiency and good selectivity. It introduces an effective, selective, and rapid method for recovery of target ssDNA of other viruses, which is very important for disease or mutant detection.

1.1. Experimental

1.1.1. Reagents and materials

Cyclohexane, n-hexanol, Triton X-100, tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS), N-(β-ethylenamine)-γ-propylamine triethoxylsilane (EPTES) and fluorscamine were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Glutaraldehyde (50%) was obtained from Amresco Chemical Company (USA). Streptavidin was from Promega Corporation (Madison, WI, USA). All DNA were synthesized at Bioasia Biologic Technology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). The DNA sequences are shown in Table 1 . All other chemicals used were analytical grade reagents and used without any further purification. All solutions were prepared with nanopured–deionized water (Branstead Co., USA).

Table 1.

Sequence of DNA probes and targets

| Capture ssDNA(I) | 5′-Biotin-AAAAAAAAAA-GTATCACGAGGCCCTATGCG-3′ |

| Target ssDNA(I) | 5′-TMR-CGCATAGGGCCTCGTGATAC-3′ |

| Capture ssDNA II | 5′-Biotin-AAAAAAAAAAGTGCTTGCACTGCTTA-3′ |

| Target ssDNA II | 3′-CACGAACGTGACGAAT-FITC-5′ |

| One base mismatch ssDNA II | 3′-CACGAACATGACGAAT-FITC- 5′ |

| Three bases mismatch ssDNA II | 3′-CACGAATGACACGAAT-FITC- 5′ |

| Random ssDNA | 3′-AAGTGTCTTATCGTGT-FITC- 5′ |

2. Instruments

The magnet property of nanoparticles was measured using an alternating gradient magnetometer (AGM, MicroMag™ 2900). The size of nanoparticles was measured with transmission electron microscope (TEM) (Hitachi-800) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) (SPM 3800N-400, Seiko). All fluorescence measurements were performed by Hitachi F-4500 Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan). UV–visible measurements were carried out by DU-800 Spectrophotometer (Beckman, England). Zeta potential was measured using the Malvern Zetasizer 3000HS (Malvern, England). Fluorescent images were taken with a Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (FV500-IX700 Olympus, Japan).

3. Experimental details

3.1. Preparation of amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles

The magnetic nanoparticles coated with amino-modified silica were prepared using the previously reported water-in-oil microemulsion [16]. First, suspension of ferrofluid was synthesized by precipitation from appropriate mixture solution of ferrous sulfate and ferric chloride with ammonia. A microemulsion formed by adding 7.2 ml of cyclohexane, 1.8 ml of n-hexanol, 1.8 ml of Triton X-100, and adequate aqueous magnetic ferrofluid (Fe3O4). In the presence of TEOS and EPTES (5:3, v/v), polymerization reaction was initiated by adding 100 μl of concentrated NH4OH. The reaction was allowed to continue for 24 h to produce magnetic nanoparticles. Then, the magnetic nanoparticles were isolated by magnetic separation and washed with ethanol and water for several times to remove all remaining material and surfactant molecules.

3.2. Characterization of amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles

Based on the results of nanoparticle's zeta potential, the proper dispersant was selected (when zeta potential >30 or ≤30 mV, nanoparticles suspension is stable and disperse) to make the nanoparticle suspension. Then, the suspension was added dropwise onto the carbon-coated copper membrane and dried at room temperature. The size of aqueous magnetic ferrofluid and amino-modified silica magnetic nanoparticles were measured by a transmission electron microscope. AFM measurements were carried out at room temperature on freshly cleaved mica foils. The magnetization properties of both the magnetic core and amino-modified silica magnetic nanoparticles have been measured by using the alternating gradient magnetometer (AGM). Amino functional groups on amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles were confirmed by fluorescent measurement of fluorescamine acetone solution (0.2 mg/ml) before and after incubation with the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticle solution.

3.3. Bio-modification of the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles

In order to recover the target ssDNA, the capture ssDNA was first immobilized onto the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles as follows: 10 mg amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles was added to 5 ml of glutaraldehyde (2.5 wt.%) and reacted at room temperature for 2 h. Then, glutaraldehyde-activated nanoparticles were washed three times with 0.01 M PBS buffer (pH 7.4) and separated under the magnet field. After that, 200 μl 1 mg/ml of streptavidin diluted in 0.01 M PBS buffer was added to the nanoparticles suspensions. Nanoparticles were washed with 0.01 M PBS buffer solution after being stirred at 4 °C for 24 h. Fluorescence spectroscopy of the supernatant was measured to determine the modification efficiency of the streptavidin. Then, 1 ml of 4.1 × 10−6 M biotin-labeled capture ssDNA(I) (5′-biotin-AAAAAAAAAAGTATCACGAGGCCCTATGCG-3′) solution was added to the streptavidin derivatived amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles and reacted at room temperature for 4 h. Then, the nanoparticles were separated from supernatant under the magnet field. The final product was washed, re-suspended in 0.01 M PBS buffer and stored at 4 °C for future use. The modification of biotin-labeled capture ssDNA(I) on the nanoparticles was investigated by measuring the absorption of biotin-labeled capture ssDNA(I) before and after reaction with the nanoparticles.

3.4. Recovery of the target ssDNA(I)

The 1 mg capture ssDNA(I)-modified amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles were re-suspended in 1 ml of hybridization buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl, 20 mM MgCl2 (pH 8.0)]. Then, 10 μl of 5.4 × 10−5 M target ssDNA I (5′-TMR-CGCATAGGGCCTCGTGATAC-3′) was added. The mixture was incubated in a 50 °C water bath for 30 min. Finally, the magnetic DNA bio-conjugate formed between the capture ssDNA(I) and its target ssDNA(I) was separated from solution under the magnet field and washed three times with 0.01 M PBS buffer. In the control experiment, only streptavidin derivative amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles was used to incubate with the target ssDNA(I).

3.5. Confirmation of the recovery

In this method, the target ssDNA is labeled with fluorophore. The recovery efficiency was determined by fluorescent measurement of target ssDNA solution before and after hybridization. The fluorescence of the dissociated target ssDNA from the magnetic DNA bio-conjugate were detected at the same time as follows. First, the separated magnetic DNA bio-conjugate was denaturalized to release the bounded target ssDNA. It was put in water bath at different temperature (55, 60, 65, 70, 80, 90, and 95 °C) for about 10 min at each temperature. The nanoparticles were separated from supernatant under the magnet field. Then, the fluorescence of the supernatant was detected. Fluorescence microscopy imaging was also used to detect whether the fluorescence-labeled target ssDNA was captured by the capture ssDNA-modified magnetic nanoparticles.

4. Results

4.1. Characterization of amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles

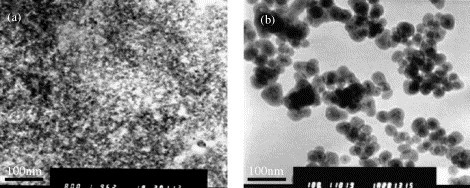

TEM images of both: (a) magnetic core and (b) amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles, are shown in Fig. 1 . The aqueous ferrofluid (magnetic core) contains regularly shaped magnetite nanoparticles with an average diameter of about 8 nm (Fig. 1a). The nanoparticles did not aggregate even after several weeks based on our experience. When the aqueous ferrofluid was treated with the W/O microemulsion in the presence of a mixture of tetraethoxysilane, N-(β-ethylenamine)-γ-propylamine triethoxylsilane and ammonia (28–30%, w/w), the magnetite core was covered by silica shell and increased the nanoparticle size up to 40 ± 5 nm (Fig. 1b). The prepared nanoparticles appeared to be homogenous with good dispersion. This sample was also examined by AFM, and the diameter was in good agreement with the result obtained from TEM. Both aqueous magnetic ferrofluid and amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles have magnetic property. Amino functional groups on the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles are important for the further modification of the magnetic nanoparticles. A significant enhancement in fluorescence of the fluorescamine solution after incubation with the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles suspension was observed in the fluorescamine tests. Thus, it can be concluded that there are –NH2 functional groups on the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles.

Fig. 1.

TEM images of: (a) magnetic core and (b) prepared amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles.

4.2. Bio-modification of the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles

The fluorescence of streptavidin solution at 340 nm decreased from 231.3 (initial solution) to 49.7, after it was reacted with the glutaraldehyde-activated amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles for 24 h. These results indicated successful modification of amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles with streptavidin. Then, this streptavidin-derivatized amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles could be used to bind the biotin-labeled capture ssDNA(I). The absorption of 4.1 μM biotin-labeled capture ssDNA(I) solution at 260 nm decreased from 1.1022 to 0.0715 in supernatant after it was incubated with the streptavidin-derivatized amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles. The aforementioned results indicated that the bio-molecules have been easily and successfully modified on the nanoparticles using the existing molecular immobilization methods through the amino groups on the nanoparticles.

4.3. Recovery of target ssDNA by using of amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles

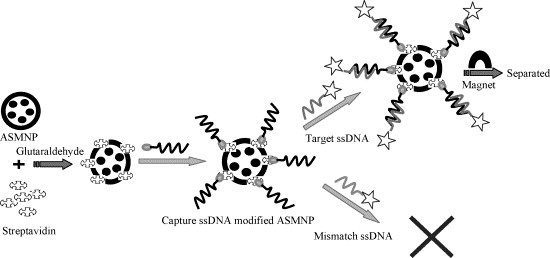

The scheme of recovery of target ssDNA based on amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles is shown in Fig. 2 . Strepavidin was first modified onto the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles. The biotin-labeled capture ssDNA was then linked with the streptavidin-activated amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles through special recognition and binding of streptavidin and biotin. The target ssDNA can be recognized and hybridized with the capture ssDNA to form the DNA bio-conjugate, and it can be separated from the solution under the magnet field due to the magnetic characteristics of the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles. However, other mismatches and non-complementary ssDNA could not be hybridized completely.

Fig. 2.

The method scheme for recovery of target ssDNA based on amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles (ASMNPs).

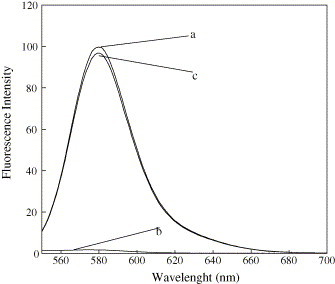

Capture ssDNA(I)-modified amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles were used to recover target ssDNA(I) in our lab. The fluorescence of the target ssDNA(I) solution obviously decreased after it was incubated with the capture ssDNA(I)-modified amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles, as shown in Fig. 3 . Meanwhile, the fluorescence intensity of the dissociated target ssDNA(I) solution increased gradually when the separated magnetic DNA bio-conjugate was denaturalized at a different temperature, as shown in Fig. 4 . After denaturalization at 95 °C, for about 10 min, the fluorescence intensity of the dissociated target ssDNA was almost the same as that of the initial target ssDNA(I) solution (Fig. 3). These results indicate that the target ssDNA(I) can be recovered from solution by this method and dissociated from magnetic DNA bio-conjugate, which can be used for further research. The fluorescence microscopy imaging of the nanoparticles also showed that the capture ssDNA(I)-modified amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles displayed intensive fluorescence after it was incubated with the fluorescence-labeled target ssDNA(I) and separated under the magnet field. After the separated magnetic DNA bio-conjugate was denatured in 95 °C water bath for 10 min and washed for several times, the fluorescence on the separated magnetic DNA bio-conjugate disappeared due to the release of the fluorescence-labeled target ssDNA(I) from the nanoparticles. In contrast, the control experiment with only streptavidin-modified amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles did not show any fluorescence after it was incubated with the fluorescence-labeled target ssDNA(I) and separated under the magnet field (Fig. 5 ). The results demonstrated that the target ssDNA(I) could be easily recovered from the solution by using the capture ssDNA(I)-modified amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles. It became clear that the existence of capture ssDNA(I) on the amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticle was the major cause of the target ssDNA(I) recovery. Therefore, this method can be widely used to recover different target ssDNA when amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles is modified with different capture ssDNA.

Fig. 3.

The emission spectrum of: (a) TMR-labeled target ssDNA(I) solution before separation; (b) TMR-labeled target ssDNA(I) solution after hybridization and separation (supernatant); (c) dissociated target ssDNA(I) solution from the separated nanoparticles DNA bio-conjugate at 95 °C water bath.

Fig. 4.

The emission spectrum of dissociated target ssDNA(I) solution from the separated nanoparticles DNA bio-conjugate at different temperature: (a) 55 °C; (b) 60 °C; (c) 65 °C; (d) 70 °C; (e) 80 °C; (f) 90 °C; (g) 95 °C, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Optical and fluorescence images of the capture ssDNA(I)-modified amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles after: (a and b) incubation with the fluorescence-labeled target ssDNA(I); (c and d) denaturalization in 95 °C water bath for 10 min; (e and f) incubation with the fluorescence-labeled target ssDNA(I).

4.4. Application of this method

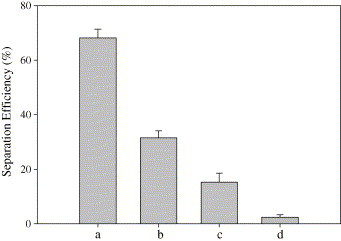

A ssDNA fragment (3′-CACGAACGTGACGAAT-FITC-5′) of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus was designed as a sample [e.g. target ssDNA(II)] and a trace amount of the sample was recovered from the solution using this method. The 4.1 μM biotin-labeled capture ssDNA(II) (5′-biotin-AAAAAAAAAAGTGCTTGCACTGCTTA-3′) was first modified onto the nanoparticles as mentioned above. The target ssDNA(II) was then added to the capture ssDNA(II)-modified nanoparticles suspension until the concentration was 6.5 nmol/l. The mixture was incubated in 50 °C water bath for 30 min. Then the magnetic DNA bio-conjugate was separated from the supernatant under the magnet field. The recovery efficiency was determined by fluorescent measurement of target ssDNA(II) solution before and after hybridization. The selectivity of this method has also been investigated by comparing the separation efficiency of target ssDNA(II) with mismatched ssDNA(II) [one base mismatch ssDNA, three bases mismatch ssDNA and random ssDNA]. Recovery efficiency of this method for target ssDNA(II) was shown in Fig. 6 . By using capture ssDNA(II), the recovery efficiency for 6.5 nmol/l target ssDNA(II) is 68.17 ± 3.29%, for one base mismatch ssDNA is 31.53 ± 2.57%, for three bases mismatch ssDNA is 15.33 ± 3.24%. The recovery efficiency for random ssDNA is very low. The above results demonstrated the recovery of target ssDNA at trace concentrations. Good selectivity was confirmed by comparing the recovery efficiency of target ssDNA with the mismatched ssDNA.

Fig. 6.

Recovery efficiency of this method for target ssDNA(II) casing for sever acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) of capture ssDNA(II)-modified amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles for: (a) complementary target ssDNA(II); (b) one base mismatch ssDNA; (c) three bases mismatch ssDNA; (d) random ssDNA.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed an improved method for recovery of target ssDNA based on amino-modified silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles. This bio-separation technology based on magnetic nanoparticles has some unique advantages over the traditional bio-separation technology. It can be done in many laboratories due to the ease on preparation, low sample consumption and simple equipment. This method has been successfully used to recover trace concentrations of a target ssDNA fragment of sever acute respiratory syndrome virus with high efficiency and good selectivity. It introduces an effective, selective, and very fast method of recovery for the target ssDNA of other viruses, which is very important for disease or mutation detection.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the National Key Basic Research Program (2002CB513100-10), High Technology Research and Development (863) Programme (2003AA302250), Key Project of Natural Science Foundation of PR China (20135010), National Science Foundation of PR China (20405005), and Key Technologies Research and Development Programme (2003 BA310A16).

References

- 1.Safarik I., Safarikova M. Monatshefte fur Chem. 2002;133:737. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter M.J., Milton I.D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1044. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.4.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle J.S., Lew A.M. Trends Genet. 1995;11:8. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)88977-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boom R., Sol C.J.A., Salimans M.M.M., Jensen C.L., Dillen P.M.E.W., Noordaa J.V. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990;28:495. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolff R.A., Hull R. Trends Genet. 1996;12:339. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(96)80007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandler D.P., Brockman F.J., Fredrickson J.K. Microbiol. Ecol. 1998;36:37. doi: 10.1007/s002489900091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandler D.P., Stults J.R., Anderson K.K., Cebula S., Schuck B.L., Brockman F.J. Anal. Biochem. 2000;283:241. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin C.R., Mitchell D.T. Anal. Chem. News Features. 1998;70:322. doi: 10.1021/ac9818430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonti S.V., Bose A. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1995;170:575. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safarik I., Safarikova M. J. Chromatogr. B. 1999;722:33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berton M., Benimetskaya L., Allemann E., Stein C.A., Gurny R. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 1999;47:119. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(98)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aboubakar M., Courreur P., Pinto-Alphandary H., Gouritin B., Lacour B., Farinottir R., Puisieux F., Vauthier C. Drug Dev. Res. 2000;49:109. [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X.X., Wang K.M., Tan W.H., Liu B., He C.M., Li D., Huang S.S., Li J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7168. doi: 10.1021/ja034450d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He X.X., Wang K.M., Tan W.H., Li J., Yang X.H., Huang S.S., Li D., Xiao D. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2002;2:317. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2002.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He X.X., Duan J.H., Wang K.M., Tan W.H., Lin X., He C.M. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2004;4:590. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2004.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He X.X., Wang K.M., Tan W.H., Xiao D., Yang X.H., Li J. SPIE. 2001;4414:394–397. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cordek J., Wang X.W., Tan W.H. Anal. Chem. 1999;71:1529. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramchand C.N., Priyadarshimi P., Kopcansky P., Mehta R.V. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. 2001;39:683. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safarikova M., Safarik I. Magn. Electron. Sep. 2001;10:223. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henglein A. Chem. Rev. 1989;89:1861. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmid G. Chem. Rev. 1992;92:1709. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alivisatos A.P. Science. 1996;271:933. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Josephson L., Tung C.H., Moore A., Weissleder R. Bioconjug. Chem. 1999;10:186. doi: 10.1021/bc980125h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bulte J.W.M., Brooks R.A. In: Scientific and Clinical Applications of Magnetic Carriers. Hafeli U., Schutt W., Teller J., Zborowski M., editors. Plenum Press; NY: 1997. pp. 527–543. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao X.J., Tapec-Dytioco R., Wang K.M., Tan W.H. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:3476. doi: 10.1021/ac034330o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan W.H., Wang K.M., Drake T.J. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:547. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]