Abstract

Summary

Genome detective is a web-based, user-friendly software application to quickly and accurately assemble all known virus genomes from next-generation sequencing datasets. This application allows the identification of phylogenetic clusters and genotypes from assembled genomes in FASTA format. Since its release in 2019, we have produced a number of typing tools for emergent viruses that have caused large outbreaks, such as Zika and Yellow Fever Virus in Brazil. Here, we present the Genome Detective Coronavirus Typing Tool that can accurately identify the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) sequences isolated in China and around the world. The tool can accept up to 2000 sequences per submission and the analysis of a new whole-genome sequence will take approximately 1 min. The tool has been tested and validated with hundreds of whole genomes from 10 coronavirus species, and correctly classified all of the SARS-related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV) and all of the available public data for SARS-CoV-2. The tool also allows tracking of new viral mutations as the outbreak expands globally, which may help to accelerate the development of novel diagnostics, drugs and vaccines to stop the COVID-19 disease.

Availability and implementation

Contact

koen@emweb.be or deoliveira@ukzn.ac.za

Supplementary information

Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 Introduction

We are currently faced with a potential global epidemic of a new coronavirus that has infected thousands of people in China and is spreading rapidly around the world. In the end of January 2020, the WHO has declared it a global emergency (WHO, 2020). The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), first isolated in Wuhan, China, has already caused more infections than the previous severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak of 2002 and 2003. The virus is a SARS-related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV), and it is genetically associated with SARSr-CoV strains that infect bats in China (Lu et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). It causes severe respiratory illness, which the WHO recently named COVID-19 disease. It has high fatality rate (Huang et al., 2020), can be transmitted from person to person, has infected over 70 000 individuals and has spread to over 30 countries in less than 2 months (WHO, 2020).

This coronavirus outbreak has been unprecedented; so too is the way that the scientific community has responded to it. They have openly and rapidly shared genomic and clinical data as never seen before allowing research results to be released almost instantaneously. This has helped the understanding of the transmission dynamics, the development of rapid diagnostic and has informed public health response. Here, we present a new contribution that can speed up this communal effort. The Genome Detective Coronavirus Typing Tool is a free-of-charge web-based bioinformatics pipeline that can accurately and quickly identify, assemble and classify coronaviruses genomes. The tool also identifies changes at nucleotides, coding regions and proteins using a novel dynamic aligner to allow tracking new viral mutations (Fig. 1).

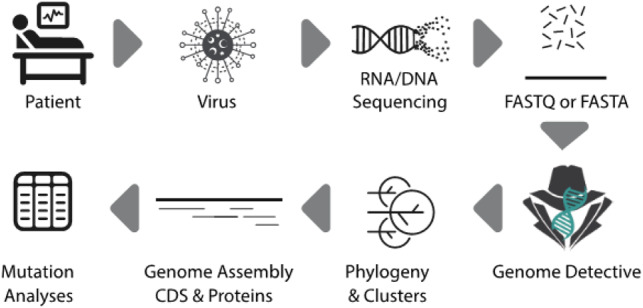

Fig. 1.

Genome Detective Coronavirus Typing Tool assembles genomes from next-generation sequencing (NGS) in FASTAQ format or assembled genomes in FASTA format. A user can submit up to 1 Gb of NGS data or 2000 assembled genomic sequences. For each assembled genomic sequence, the tool identifies the virus species, constructs a phylogenetic tree and identifies phylogenetic clusters, which includes the novel coronavirus identified in Wuhan, China in 2019 (SARS-CoV-2). The tool identifies changes at nucleotides, coding regions and proteins using a novel dynamic aligner and display all of the mutations in detailed tables and reports

2 Systems and methods

A reference dataset of previously published coronavirus whole-genome sequences (WGS) was compiled from the Virus Pathogen Resource (VIPR) database (www.viprbrc.org). This dataset consisted of 386 WGS of nine important coronavirus species. These included 132 sequences of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome related Coronavirus (SARSr-CoV), 121 sequences of Beta coronavirus, 97 sequences of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome related Coronavirus (MERSr-CoV), 19 sequences of Human Coronavirus HKU1, 9 sequences of Murine Hepatitis Virus, 4 of Rousettus Bat Coronavirus HKU9, 3 of Rat Coronavirus and 1 WGS of Tylonycteris Bat Coronavirus HKU4, Zaria_bat_coronavirus and Longquan Rl Rat coronavirus. To this reference dataset, we added 47 whole genomes of the current Coronavirus 2019 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak that originated in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. The SARS-CoV-2 sequences were downloaded from the GISAID database (https://www.gisaid.org) together with annotation of its original location, collection date and originating and submitting laboratory. The SARS-CoV-2 data generators are properly acknowledged in the acknowledgements section of this article and detailed information is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

The 431 reference WGS were aligned with MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). The alignment was manually edited until a codon alignment was attained in all coding sequences (CDS). A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree, 1000 bootstrap replicates were constructed in PhyML (Guindon and Gascuel, 2003; Lemoine et al., 2018) and a Bayesian tree using MrBayes (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) were constructed. The trees were visualized in Figtree (Rambaut, 2018). We selected 25 reference sequences that represent the diversity of each well-defined phylogenetic cluster (with bootstrap support of 100% and posterior probability of 1). We identified five well-supported phylogenetic clusters with more than two sequences of SARSr-CoV and used them to set up our automated phylogenetic classification tool. Cluster 1 included SARS strains from the 2002 and 2003 Asian outbreaks. In our tool, we named this cluster SARS-CoV Outbreak 2000s but may rename it as SARS-CoV-1 if a new proposed naming system for SARSr-Cov is adopted in the near future. Cluster 2 (provisionally named as SARS related CoV) includes seven sequences from bats which did not cause large human outbreaks. Cluster 3 (named as Bat SARS-CoV HKU3) includes three WGS sampled from Rhinolophus sinicus (i.e. Chinese rufous horseshoe bats). Cluster 4 (Bat SARS-CoV ZXC21/ZC45) includes two SARSr-CoV sampled from Rhinolophus sinicus bats in Zhoushan, China. Cluster 5 (virus named SARS-CoV-2 by the ICTV committee and disease named COVID-19 by the WHO) includes three public sequences from the outbreak. We identified this cluster with many sequences from GISAID but kept only three ones as these were the first GenBank sequences. The first whole genome of SARS-CoV-2 was kindly shared by Prof. Yong-Zhen Zhang and colleagues in the virological.org website. Detailed information about the phylogenetic reference datasets is available in Supplementary Table S2.

The phylogenetic reference dataset was used to create an automated Coronavirus Typing Tool using the Genome Detective framework (Fonseca et al., 2019; Vilsker et al., 2019). To determine the accuracy of this tool, each of the 431 test WGS was considered for evaluation (i.e. 384 reference sequences from VIPR and 47 public SARS-CoV-2 sequences). The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of our method were calculated for both species assignment and phylogenetic clustering of SARSr-CoV. Sensitivity was computed by the formula, specificity by and accuracy by , where TP = True Positives, FP = False Positives, TN = True Negatives and FN = False Negatives.

Classifying query sequences in an automated fashion involves two steps. The first step enables virus species assignments and the second, which is restricted to SARSr-CoV, includes phylogenetic analysis. The first classification analysis subjects a query sequence to BLAST and AGA analysis. AGA is a novel alignment method for nucleic acid sequences against annotated genomes from NCBI RefSeq Virus Database. AGA (Deforche, 2017) expands the optimal alignment algorithms of Smith and Waterman (1981) and Gotoh (1982) based on an induction state with additional parameters. The result is a more accurate aligner, as it takes into account both nucleotide and protein scores and identifies all of the polymorphisms at nucleotide and amino acid levels. In the second step, a query sequence is aligned against the phylogenetic reference dataset using -add alignment option in the MAFFT software (Katoh and Standley, 2013). In addition, a Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree is constructed using the HKY distance metric with gamma among-site rate variation with 1000 bootstrap replicates using PAUP* (Swofford, 2003). The query sequence is assigned to a particular phylogenetic cluster if it clusters monophyletically with that clade or a subset of it with bootstrap support >70%. If the bootstrap support is <70%, the genotype is reported to be unassigned.

The result of the phylogenetic and mutational analysis performed by AGA is available in a detailed report. This report contains an interactive phylogenetic tree and genome mapper (Supplementary Fig. S1). It also presents the virus species and cluster assignments and a detailed table that provides information about open reading frames (ORFs), CDS and proteins. This table can be expanded to show nucleotide and amino acid mutations that differentiate a query sequence from their species RefSeq or from a sequence in the phylogenetic reference dataset. All results can be exported to a variety of file formats (XML, CSV, Excel, Nexus or FASTA).

3 Testing and validation

The Genome Detective Coronavirus Typing Tool correctly classified all of the 175 SARSr-CoV sequences at species level, i.e. specificity, sensitivity and accuracy of 100%. Furthermore, all of the 47 SARS-CoV-2 WGS that were isolated in China (n = 36), USA (n = 5), France (n = 2), Thailand (n = 2), Japan (n = 1) and Taiwan (n = 1) were correctly classified at phylogenetic cluster level as SARS-CoV-2, which may be renamed as SARS-B. In addition, we classified with very high specificity, sensitivity and accuracy (i.e. 100%) all of the 112 SARS outbreak WGS of 2002 and 2003. We also achieved perfect classification (i.e. specificity, sensitivity and accuracy of 100%) for all of Beta coronavirus, Human_coronavirus_HKU1, MERS-CoV, Rousettus Bat coronavirus HKU9 and Tylonycteris_bat_coronavirus_HKU4 at species level. For a detailed overview of assignment performance, please refer to the Supplementary Table S3.

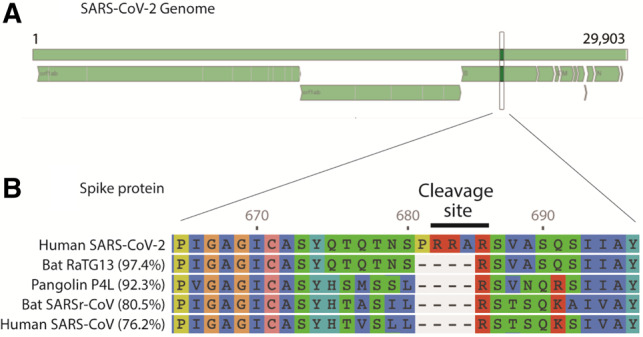

Our tool also allows detailed analysis of coding regions and proteins for each of the coronavirus species. For example, the analysis of the first released SARS-CoV-2 sequence, the WH_Human1_China_2019Dec (GenBank: MN908947) demonstrated at genome level, the nucleotide (NT) identity was 79.0% to the reference strain of SARSr-CoV (ACCESSION: NC_004718.3) and that the Envelop Small Membrane Protein (protein E) is the most similar protein. In total, 94.8% (73/77) of the amino acids were identical; the four amino acid differences were located at positions 55 (T55S), 56 (V56F), 69 (69deletion) and 70 (G70R). The spike protein (protein S), which can be associated with virulence, was 76.2% identical to the reference strain of SARSr-CoV (Supplementary Table S4A). Interestingly, there were four amino acid insertions at position 237 (A237_F238insHRSY, genome NT position 22202_22203insCATAGAAGTTAT), which is just upstream from a cleavage site. There is also a four amino acid insertion PRRA at the spike protein at positions 681 to 684. This is at the junction of S1 and S2 and creates a new polybase cleavage site. Our tool also allows us to compare mutations with other-related sequences, such as the Pangolin, Bat RaTG13, the Bat SARS-CoV and SARS Sin940 (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S2). The most diverse coding regions were the CDS Sars8a and Sars8b. In these two regions, only 30% of the amino acids were identical. Sars8b protein was truncated early and its CDS had four stop codons (Supplementary Table S4A).

Fig. 2.

Output from Genome Detective Coronavirus Typing Tool showing: (A) SARS-CoV-2 complete genome map. Top bar represents the genome (nucleotide positions 1 to 29 903). Bottom segments represent the open reading frames (ORFs). (B) Amino-acid alignment of the spike protein highlighting a four amino acid insertion (PRRA), which creates a new polybase cleavage site (RRAR) for SARS-CoV-2. Amino acid (aa) alignment is compared with four-related coronaviruses. The tool also calculates the percentage aa identities with reference to SARS-CoV-2 as shown here for the complete (1274 aa) spike protein

Our Coronavirus Typing Tool also allows a query sequence to be analyzed against a sequence in the phylogenetic reference dataset. For example, the WH_Human1_China_2019Dec (GenBank: MN908947) the identity was 87.5% to the Bat sequence bat_SL_CoVZXC21 (Genbank: MG772934). This was one of the Bat-CoV sequences that were most related to n2019-CoV (Lu et al., 2020). The Envelop Small Membrane Protein (protein E) was 100% identical (Supplementary Table S4B). When the SARS-CoV-2 isolated from France (BetaCoV/France/IDF0373/2020) was analyzed with our tool and compared with the SARS-CoV-2 WH_Human1_China_2019Dec strain (Accession: MN908947), this sequence was 99.9% identical and had only two NT mutations (Supplementary Table S4C). These two differences were located on positions: 22551G>T and 26016G>T, which caused three amino acid mutations (E2 glycoprotein Protein mutation: V354F (22551G>T), sars3a protein mutations: G250V (26016G>T) and sars3b protein mutations: V110F (26016G>T) (detailed in Supplementary Table S4C-II). The analysis of a WGS in FASTA format takes approximately 60 s.

4 Discussion

We developed and released the Genome Detective Coronavirus Typing tool as a free-of-charge resource in the third week of January 2020 in order to help the rapid characterization of COVID-19 infections. This tool allows the analysis of whole or partial viral genomes within minutes. It accepts assembled genomes in FASTA format or raw next-generation sequencing data in FASTQ format from Illumina, Ion Torrent, PACBIO or Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) can be submitted to the Genome Detective Virus Tool (Vilsker et al., 2019) to automatically assemble the consensus genome prior to executing the Coronavirus Typing Tool. User effort is minimal, and a user can submit multiple FASTA sequences at once.

The tool uses a novel and dynamic aligner, AGA, to allow submitted sequences to be queried against reference genomes, using both nucleotide and amino acid similarity scores. This allows accurate identification of other coronavirus species and the tracking of new viral mutations as the outbreak expands globally. It also performs detailed analysis of the coding regions and proteins. Moreover, it can easily be updated to add new phylogenetic clusters if new outbreaks arise or if the classification nomenclature changes. The tool has been able to correctly classify all the recently released SARS-CoV-2 genomes, as well as all the 2002–2003 SARS outbreak sequences.

In conclusion, the Genome Detective Coronavirus Typing Tool is a web-based and user-friendly software application that allows the identification and characterization of novel coronavirus genomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Genome data for SARS-CoV-2 made kindly available by National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention (ICDC) Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC), Institute of Pathogen Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Hubei Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, China CDC, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, the University of Hong Kong, Department of Medical Sciences, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand | Thai Red Cross Emerging Infectious Diseases—Health Science Centre | Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, Department of Microbiology, Guangdong Provincial Center for Diseases Control and Prevention, Department of Microbiology, Zhejiang Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Viral Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control, R.O.C. (Taiwan) | Centers for Disease Control, R.O.C. (Taiwan), California Department of Public Health | Pathogen Discovery, Respiratory Viruses Branch, Division of Viral Diseases, Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention, Arizona Department of Health Services | Pathogen Discovery, Respiratory Viruses Branch, Division of Viral Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Guangdong Provincial Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention | Guangdong Provincial Institute of Public Health, University of Hong Kong-Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, Guangdong, State Key Laboratory of Virology, Wuhan University, Department of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Bichat Claude Bernard Hospital, Paris | National Reference Center for Viruses of Respiratory Infections, Institute Pasteur, Paris. We would like to acknowledge all of the data contributors.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by a research Flagship grant from the South African Medical Research Council (MRC-RFA-UFSP-01-2013/UKZN HIVEPI), the VIROGENESIS project, which received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (under Grant Agreement no. 634650) and the National Human Genome Research Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U24HG006941. H3ABioNet is an initiative of the Human Health and Heredity in Africa Consortium (H3Africa). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest: Emweb bv is the company that makes the Genome Detective Coronavirus Typing Tool online available. S.C. is employee of emweb bv. K.D. and W.D. are directors and owners of emweb bv. This company has allowed the coronavirus typing tool to freely available on the web.

References

- Deforche K. (2017) An alignment method for nucleic acid sequences against annotated genomes. Biorxiv. doi:10.1101/200394.

- Edgar R.C. (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res., 32, 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca V. et al. (2019) A computational method for the identification of Dengue, Zika and Chikungunya virus species and genotypes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., 13, e0007231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh O. (1982) An improved algorithm for matching biological sequences. J. Mol. Biol., 162, 705–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Gascuel O. (2003) A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol., 52, 696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. et al. (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet, 395, 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D.M. (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol., 30, 772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine F. et al. (2018) Renewing Felsenstein’s phylogenetic bootstrap in the era of big data. Nature, 556, 452–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R. et al. (2020) Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet, 395, 565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. (2018) FigTree v1.4.4. Institute of Evolutionary Biology University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh. http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (31 January 2020, date last accessed).

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J.P. (2003) MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics, 19, 1572–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T.F., Waterman M.S. (1981) Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol., 147, 195–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D.L. (2003) PAUP* 4.0: Phylogenetic Analysis Under Parsimony (And Other Methods), Version 4.0b2a. Sinauer Associates Inc., Sunderland, MA.

- Vilsker M. et al. (2019) Genome Detective: an automated system for virus identification from high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics, 35, 871–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Situational Reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/ (17 February 2020, date last accessed).

- Zhu N. et al. ; China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team (2020). A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med, 382, 727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.