The p.D202N mutation in PRNP is a rare variant associated with Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease (GSS), a genetic form of prion cerebral amyloidosis. To date, there have been only 4 reports of this mutation worldwide and only one detailed clinical study (table e-1, links.lww.com/NXG/A223).1–4 Here, we describe the clinical phenotype and the results of neuroradiologic and laboratory investigations in an Italian patient carrying this genetic variant.

Case report

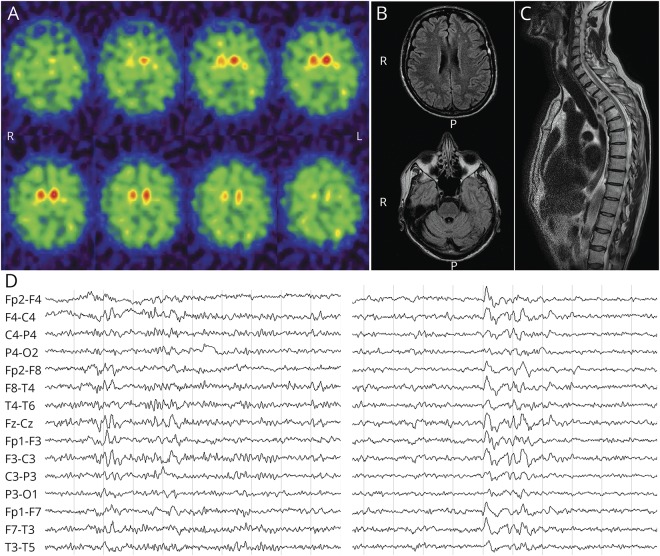

A 59-year-old Caucasian man, with no family history of neurologic disorders, presented with a 2-year history of slurred speech and progressive gait difficulties causing motor slowing and accidental falls. In the same period, he lost 14 kg and developed urinary incontinence. His medical history was relevant to hypertension. Neurologic examination revealed ideomotor slowing, smooth pursuit deficit, dysarthria, dysmetria, axial and limb plastic hypertonia, brisk deep tendon reflexes, Babinski sign, and ataxic gait. Given the clinical findings, the suspicion of multiple system atrophy (MSA) was raised. Repeated neuropsychological testing revealed abnormalities in attention, constructive praxis, lexical access, and verbal memory span, consistent with a multiple domain cognitive impairment (table e-2, links.lww.com/NXG/A223). 123I-ioflupane single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) (DaTscan) showed reduced presynaptic dopamine transporter uptake in the right caudate and putamen bilaterally (figure 1A). Brain MRI displayed multiple, small hyperintense foci in subcortical white matter and right putamen in T2 sequences, whereas diffusion-weighted imaging was negative (figure 1B). Spinal MRI was unremarkable, except for a tiny C5-C6 disc protrusion (figure 1C). Somatosensory-evoked potentials revealed symmetrically delayed spinal conduction and a reduced motor response from the right lower leg. Electroneurography and sympathetic skin response were normal. EEG showed discharges of slow waves, occasionally pseudorhythmic and sharp, favored by drowsiness but lacking a definite periodism (figure 1D). CSF analyses revealed a positive 14-3-3 protein assay, markedly increased total-tau (3,617 pg/mL, n.v. 44–298) and phosphorylated-tau (337 pg/mL, n.v. 35–66), and normal amyloid-beta 1–42 (982 pg/mL, n.v. 562–1,018). The CSF prion real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) assay was negative. Direct sequencing of the PRNP open reading frame revealed a point mutation at codon 202 (p.D202N), causing the substitution of aspartic acid for asparagine (figure e-1, links.lww.com/NXG/A223) and valine homozygosity at codon 129. The patient lost the walking ability 3 years after the clinical onset; at this time, the patient developed dysphagia, and his speech became unintelligible because of severe dysarthria, but comprehension was relatively spared. The patient died 4.5 years after the onset because of sepsis complications. An autopsy was not performed.

Figure 1. Neurophysiologic and neuroimaging findings.

(A) 123I-ioflupane SPECT (DaTscan) showing an abnormally reduced uptake in the right caudate nucleus and both putamen nuclei. (B) A few small, focal hyperintensities in the frontal subcortical white matter on brain MRI fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence. (C) Spinal MRI demonstrating a tiny C5-C6 disc protrusion. (D) EEG recording showing some bursts of diffuse slow waves (left), promoted by drowsiness (right). R = right, L = left; P = posterior.

Discussion

GSS is a genetic prion disease caused by several point (i.e., missense, nonsense) or insertional mutations in PRNP.5 The clinical phenotype of GSS is heterogeneous and may include ataxia, spastic paraparesis, cognitive decline, and amyotrophy as presenting signs. Parkinsonism may also occur,5 but not as the dominant clinical feature, especially at disease onset. As the most significant exception, patients with GSS carrying the p.D202N substitution consistently showed early extrapyramidal features, often raising the suspicion of atypical parkinsonian syndrome. Notably, family history was strongly positive for parkinsonism in one case (i.e., overall 9 subjects in 5 generations), with the proband's mother and cousin being diagnosed with progressive supranuclear palsy.2,4 In line with these observations, 123I-ioflupane SPECT (DaTscan) gave abnormal results in both patients who underwent this test (table e-1, links.lww.com/NXG/A223). In our patient, parkinsonism was not either dominant or isolated at disease onset, but the concurrence of parkinsonism with ataxia and pyramidal signs raised the suspicion of MSA, which belongs to the spectrum of atypical parkinsonisms.

The causative role of the p.D202N mutation in our patient is supported by the similar presentation among reported cases.2–4 and the neuropathologic studies documenting a genuine GSS phenotype in 3 previously described cases carrying the p.D202N mutation examined neuropathologically, a phenotype which has never been reported to date in a subject carrying the wild-type PRNP sequence.1–3 However, given the absence of a positive family history in the present case (as well in others),4 we cannot definitely rule out the possibility of an incomplete penetrance of the p.D202N variant.

It is well established that the methionine (M)/valine(V) polymorphism at PRNP codon 129 strongly modulates the disease phenotype of human prion disease.6 In GSS-p.D202N, the mutation cosegregated with V129. Indeed, valine homozygosity at codon 129 was documented in 3 patients, and the mutation was in cis with valine in a fourth case (table e-1, links.lww.com/NXG/A223).

Of interest, the CSF profile in our cases indicated a severe neurodegenerative process associated with the accumulation of phosphorylated tau protein, without a concomitant A-Beta protein deposition.7 This finding is also in line with the diagnosis of GSS, given that the secondary tau-positive neurofibrillary pathology is a neuropathologic hallmark of GSS5,e1 and also occurred in the 3 previously described cases carrying the p.D202N variant.1–3 Finally, the negative CSF prion RT-QuIC result is not surprising because, despite the few cases analyzed, the suboptimal diagnostic accuracy of this assay for GSS has been already reported by different groups.e2-e4

Our and previous observations underline the importance of considering the GSS-p.D202N-V129 variant in the differential diagnosis of patients with atypical parkinsonism, especially when associated with cerebellar and/or pyramidal signs and dementia.

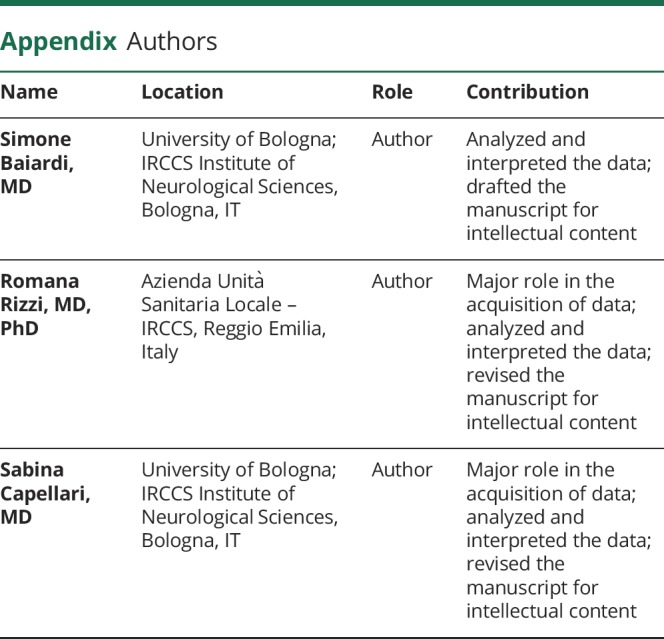

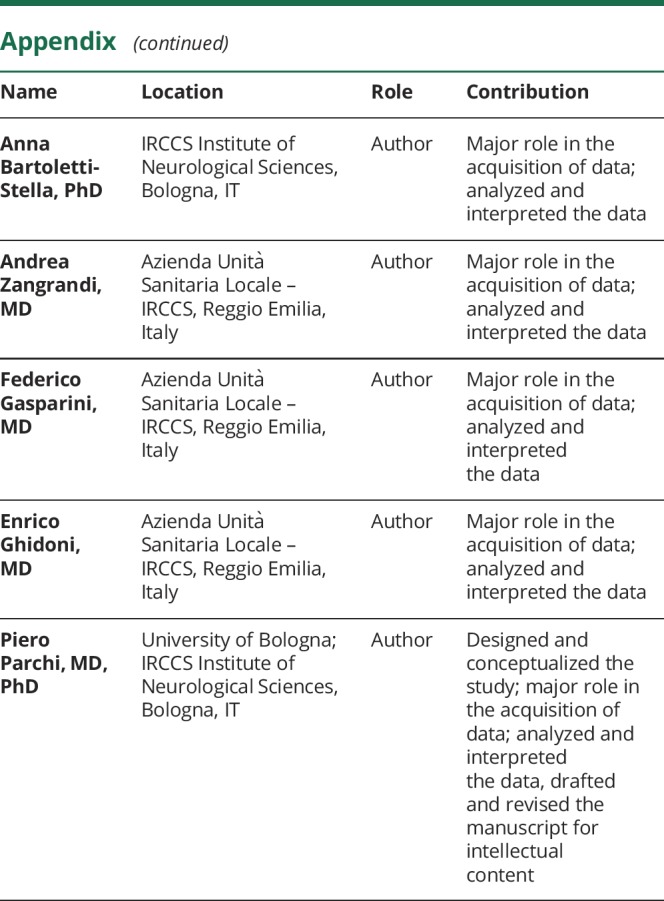

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

Disclosures available: Neurology.org/NG.

References

- 1.Piccardo P, Dlouhy SR, Lievens PM, et al. Phenotypic variability of Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease is associated with prion protein heterogeneity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1998;57:979–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kong Q, Surewicz WK, Petersen RB, et al. Inherited prion diseases. In: Prusiner SB, Prion Biology and Diseases. 2nd ed Woodbury: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2004:673–776. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming AB, Ghetti B, Murrell IR, et al. Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease with progressive supranuclear palsy presentation. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2010;30(1 suppl):43.20689282 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plate A, Benninghoff J, Jansen GH, et al. Atypical parkinsonism due to a D202N Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker prion protein mutation: first in vivo diagnosed case. Mov Disord 2013;28:241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghetti B, Piccardo P, Zanusso G. Dominantly inherited prion protein cerebral amyloidoses—a modern view of Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker. Handb Clin Neurol 2018;153:243–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baiardi S, Rossi M, Capellari S, Parchi P. Recent advances in the histo-molecular pathology of human prion disease. Brain Pathol 2019;29:278–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. A/T/N: an unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology 2016;87:539–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Data available from supplement data (References e1–e4): links.lww.com/NXG/A223