Abstract

Positive symptoms of schizophrenia and its extended phenotype—often termed Psychoticism or positive schizotypy—are characterized by the inclusion of novel, erroneous mental contents. One promising framework for explaining positive symptoms involves “apophenia,” conceptualized here as a disposition toward false positive errors. Apophenia and positive symptoms have shown relations to Openness to Experience (more specifically, to the openness aspect of the broader Openness/Intellect domain), and all of these constructs involve tendencies toward pattern seeking. Nonetheless, few studies have investigated the relations between Psychoticism and non-self-report indicators of apophenia, let alone the role of normal personality variation. The current research used structural equation models to test associations between Psychoticism, openness, intelligence, and non-self-report indicators of apophenia comprising false positive error rates on a variety of computerized tasks. In Sample 1, 1193 participants completed digit identification, theory of mind, and emotion recognition tasks. In Sample 2, 195 participants completed auditory signal detection and semantic word association tasks. Psychoticism and the openness aspect were positively correlated. Self-reported Psychoticism, openness, and their shared variance were positively associated with apophenia, as indexed by false positive error rates, whether or not intelligence was controlled for. Apophenia was not associated with other personality traits, and openness and Psychoticism were not associated with false negative errors. Findings provide insights into the measurement of apophenia and its relation to personality and psychopathology. Apophenia and pattern seeking may be promising constructs for unifying the openness aspect of personality with the psychosis spectrum and for providing an explanation of positive symptoms. Results are discussed in the context of possible adaptive characteristics of apophenia, as well as potential risk factors for the development of psychotic disorders.

Keywords: Schizotypy, Openness to Experience, False Positives, Schizophrenia, Intelligence

General Scientific Summary

Our research using two samples taken from the general population suggests that the personality aspect of openness (individual differences in creativity and imagination, representing half of a broader Openness/Intellect trait) and symptoms of the psychosis spectrum are related to each other and may share underlying mechanisms. In the current work, we provide novel evidence that apophenia—the tendency to observe meaningful patterns where there are none present—may be an important cognitive mechanism at the core of what is shared between openness and risk for psychosis.

Psychosis refers to a loss of contact with reality that is present in various forms of psychopathology, most prominently schizophrenia. Symptoms of schizophrenia involve maladaptive alterations in affect, cognition, and behavior, and are typically separated into negative, disorganized, and positive symptoms. Negative symptoms include constricted affect, anhedonia, and social withdrawal. Disorganized symptoms consist of disrupted thought processes that can produce incoherent or bizarre speech and behavior. Positive symptoms—hallucinations and delusions—are perhaps the most recognizable and defining feature of psychotic disorders, described as “positive” because they involve the addition of novel and erroneous mental content. One construct that may be useful for understanding positive symptoms across psychotic disorders is apophenia.

The term apophenia was coined by Klaus Conrad to describe a core feature of psychosis: the perception of meaningful patterns where none, in fact, exist (Mishara et al., 2009). In our current conceptualization, apophenia can be seen as synonymous with a disposition toward Type I errors (false positives) in both perception (as in hallucinations) and belief (as in delusions). This conceptualization of apophenia is in line with the concept of aberrant salience—the inappropriate assignment of attention or meaning to external objects and internal representations—a proposed mechanism of psychosis that fits well into broader theoretical frameworks involving the function of dopamine in salience and pattern detection (Kapur, 2003). Apophenia may involve the assignment of unwarranted salience to information in one’s environment, thus leading to an increase in false positive errors. These tendencies may remain relatively widespread throughout the population, because in healthy functioning, things perceived as salient are likely to involve real and meaningful patterns.

Given that hallucinations and delusions can both be seen as severe instances of Type I errors, it is not surprising that individuals with schizophrenia show high rates of such errors in behavioral tasks (Blakemore et al., 2003). Apophenia is not limited to those with severe psychopathology, though, and it also occurs regularly throughout the general population. Apophenia, as understood today, can include any instance in which a pattern is falsely detected or labeled as meaningful when it is actually absent or attributable to chance. Everyday examples could include believing your name was called when hearing random sounds, seeing animals in the clouds, and believing in concepts such as astrology or good-luck charms. Importantly, apophenia may be the result of heightened pattern seeking, which leads to increased rates of false positive errors, as a tradeoff for decreased false negative (Type II) errors. However, high levels of pattern seeking are not identical to apophenia. The result of a sensitive pattern detection system can be either adaptive (e.g., innovative) or maladaptive (e.g., departing from reality), but if it is to be adaptive, it must be accompanied by the capacity to distinguish between true and false patterns among those detected (DeYoung et al., 2012).

The majority of existing research on apophenia has operationalized the construct using self-report measures assessing positive symptoms of schizophrenia and its extended phenotype—schizotypy. Individual differences in schizotypy are conceptualized as variation in traits that are continuously distributed and correspond to the positive, negative, and disorganized symptoms of schizophrenia (Kwapil & Barrantes-Vidal, 2014). Positive schizotypy, also known as Psychoticism, is associated with ideas of reference, magical thinking, and unusual perceptual experiences—milder versions of delusions and hallucinations (Krueger et al., 2012). This construct should not be confused with Eysenck’s psychoticism, a misleadingly named trait reflecting impulsive nonconformity, low agreeableness, and low conscientiousness, but not psychosis proneness (Knezevic et al., 2019). Advantages of studying Psychoticism in the general population include (1) fewer confounds stemming from use of psychoactive medications, comorbidity, and functional impairment, (2) greater capacity to participate in research, and (3) a broader range of the variables of interest. Though previous attempts to measure and characterize apophenia have largely focused on self-report measures designed to assess Psychoticism and related traits (e.g., DeYoung et al., 2012), a handful of studies have also attempted to measure apophenia with behavioral tasks (Brugger & Graves, 1997; Chen et al., 1998; Fyfe et al., 2008; Galdos et al., 2010; Grant et al., 2014; Mohr et al., 2001).

Although existing research on the non-self-report assessment of apophenia is somewhat sparse, we now provide an overview. Brugger and Graves (1997) assessed apophenia using a task in which participants are asked to complete a short puzzle game with reinforcement based on participants’ response time; after the puzzle task, participants are asked whether other aspects of their behavior (which did not, in reality, influence reinforcement frequency) were related to reinforcement frequency. Another task used to assess apophenia is a theory of mind test in which simple geometric shapes move in ways that are either social or random in nature (in the social condition, the shapes move like interacting agents, and most people can clearly recognize behaviors such as help-seeking, encouragement, fear, etc.); participants are asked to label the motion in each trial as either social or random (Fyfe et al., 2008). Galdos (2010) used an auditory signal detection task in which participants listen to white noise and speech masked with white noise, and are asked to indicate whether or not speech was present. Grant (2014) used a word detection task in which participants are asked to state whether words or non-words were present inside 15 letter strings. Finally, word association tasks are used to assess apophenia by asking participants whether or not a series of word pairs or groups are semantically related (Mohr et al., 2001). Across the aforementioned tasks and studies, false positive errors and erroneous associations were positively associated with Psychoticism.

A major weakness for many of these studies has been use of only a single task at a time to assess apophenia. False positives on any given task may be influenced by aspects of task-specific performance that are irrelevant to a general tendency toward apophenia. In the present study, therefore, we use multiple tasks and a latent variable approach to assess the general tendency toward false positive errors. Furthermore, the current research uses two large community samples with a total of 1388 participants, an obvious improvement over the majority of previous studies on this topic, which have typically used single samples with fewer than 100 participants (e.g., Brugger & Graves, 1997; Fyfe et al., 2008; Mohr et al., 2001).

Although apophenia has been primarily studied in relation to Psychoticism, elements of normal personality may also play a role. Efforts are increasingly being made to integrate models of normal personality and psychopathology, due to the recognition that the major dimensions of risk for psychopathology correspond fairly closely to dimensions of normal personality (DeYoung & Krueger, 2018; Kotov et al., 2016). The Five-factor Model or Big Five is well-established as a description of the major dimensions of normal personality variation, and four of its dimensions (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness) clearly correspond to major dimensions of psychopathology (Negative Affect or Internalizing, Detachment, Antagonism, and Disinhibition, respectively). Psychoticism has been the dimension of psychopathology most difficult to integrate with normal personality models because it often does not seem to correspond well with the Openness/Intellect dimension of the Big Five, despite theoretical expectations that Psychoticism resembles maladaptive openness and occasional empirical associations consistent with those expectations (De Fruyt et al., 2013; Lo et al., 2017; Piedmont, et al., 2009; Suzuki et al., 2015).

Recent empirical developments have clarified the source of this difficulty. Despite its frequent use as the label for one of the Big Five dimensions, “Openness to Experience” is actually just one of two major subfactors or aspects of the broader Openness/Intellect dimension, with the other being intellect (DeYoung et al., 2007). The openness aspect encompasses fantasy-proneness and aesthetic interests, whereas intellect reflects intellectual confidence and intellectual engagement. (When we use the term “openness” by itself, we are referring to the subfactor, never the broader Openness/Intellect dimension.) Although apophenia and Psychoticism are typically at least weakly negatively associated with IQ and intellect, they are positively associated with openness and can be conceived as maladaptive variants of this personality trait, forms of “openness to implausible patterns” (Chmielewski et al., 2014; DeYoung et al., 2012, 2016; Wiggins & Pincus, 1989). A number of studies show that Psychoticism and openness share variance, though often less than the other Big Five traits and their psychopathological variants, at least in part because their association is suppressed by their opposite associations with intellect and IQ (DeYoung et al., 2012, 2016; Chmielewski et al., 2014). Further, although Psychoticism, like almost all forms of psychopathology, has a sizeable association with Neuroticism, it loads primarily on a factor with openness, not Neuroticism, when intellect and openness are measured separately (De Fruyt et al., 2013; DeYoung et al., 2012, 2016). Additionally, evidence suggests at least partially overlapping biological correlates of openness and Psychoticism (Blain et al., 2019; Grazioplene et al., 2016; Jung et al., 2010; Smeland et al., 2017; Wright et al., 2017). Finally, another possible confound in clearly establishing a relation between Psychoticism and openness is failure to separate positive and negative schizotypy dimensions, as negative schizotypy is negatively related to openness (Chmielewski et al., 2014; Ross, et al., 2002). The present research seeks to clarify the relation between openness and Psychoticism by examining their association with non-self-report measures of apophenia.

When studying the role of apophenia in Psychoticism and openness, it is important to consider more general cognitive deficits as well. Low intelligence is a common risk factor for most forms of psychopathology and may confer particular vulnerability to schizophrenia (Khandaker et al., 2011; Zammit et al., 2004). Moreover, individuals with psychosis show specific deficits in social cognition and working memory (Mier & Kirsch, 2015; Park & Holzman, 1992), and Psychoticism is also negatively correlated with performance in these domains (Blain et al., 2017; Park et al., 1997). Pertinent to the current study, intelligence is positively associated with stimulus discrimination (Melnick et al., 2013) and inversely associated with tendencies toward Type I errors (Tomporowski & Simpson, 1990). Research and theory suggest that intelligence may moderate the association between apophenia and dysfunction (DeYoung et al., 2012; Grant et al., 2014). Therefore, when examining associations between Psychoticism and apophenia, it is important to control for covariance explained by general cognitive ability. Few studies have examined the relation between Psychoticism and non-self-report indices of apophenia in large community samples, and even fewer have considered the possible explanatory roles of intelligence and openness.

The current research sought to overcome these limitations and also incorporated a multi-indicator design that assessed apophenia using a variety of computerized tasks, representing a range of perceptual and cognitive domains. As noted above, behavior in any given task is influenced by a number of task-specific factors, such that measuring a construct reliably using tasks and avoiding underestimation of true effect sizes typically requires multiple tasks. Indeed, research suggests that the psychometric quality of individual behavioral tasks is often deficient and that using multi-indicator designs in a latent variable modeling framework can correct many such deficiencies (Campbell et al., 1959; Nosek et al., 2007). This is likely to be especially important when assessing the tendency toward broad classes of error, across diverse tasks, because errors on any single task should be influenced by specific abilities and reactions to that particular task, as well as by the general tendency toward a given type of error (in this case Type I errors).

As Psychoticism, openness, and apophenia all involve tendencies toward pattern seeking and perceptual sensitivity, they can be expected to share at least a moderate amount of variance. In the current research, we attempted to clarify relations among these constructs. Specifically, we investigated the relations among self-report measures of Psychoticism, openness, and apophenia as indexed by false positive errors across a range of behavioral tasks that require participants to draw connections or detect patterns. We hypothesized that latent factors corresponding to Psychoticism and openness would be positively correlated and that Psychoticism, openness, and a latent factor accounting for their shared variance would be associated positively with participants’ disposition toward false positive responses. Finally, we anticipated these patterns of association would be specific to false positive errors, rather than also generalizing to variance shared with or specific to false negative errors.

Methods and Materials

Participants

Sample 1 included 1193 participants (656 females) from the Human Connectome Project. The sample included individuals between the ages of 22 and 37 (M = 28.8, SD = 3.7). Exclusion criteria included a history of severe psychiatric, neurological, or medical disorders. Participants were not excluded for mild to moderate psychopathology (i.e., psychopathology that did not result in hospitalization or treatment over a period of greater than one year). Thus, given population estimates, approximately 15–20% of the sample would likely warrant a DSM-5 diagnosis (National Institute of Mental Health, 2017).

Sample 2 included 195 undergraduate participants (119 females) between the ages of 18 and 44 (M = 21.1, SD = 4.8) recruited on the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campus. They were not screened or excluded for psychiatric illness.

Self-report Measures

Sample 1

NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992).

The NEO-FFI is a measure of the Big Five personality traits. It consists of 60 items taken from the longer NEO Personality Inventory, Revised (NEO PI-R [Costa & McCrae, 1992]) and uses a five-point Likert scale. The NEO-FFI does not include subscales for openness and intellect within the broader Openness/Intellect factor; thus, in order to create an openness aspect scale, correlations of items from the full NEO-FFI Openness scale were examined in relation to openness and intellect scales from the Big Five Aspect Scales (BFAS [DeYoung et al., 2012]). Previous work has been done to extract a similar openness aspect scale designed using the full NEO PI-R, based on item-associations with the BFAS in three independent samples (Ross & DeYoung, 2018); this latter scale has been used in previous research examining relations of openness and intellect with Psychoticism (Suzuki et al., 2016). Items from this NEO PI-R openness scale that are also included in the NEO-FFI were selected to create an FFI openness scale for use in the current research. These included “I don’t like to waste my time daydreaming (reverse coded),” “I am intrigued by the patterns I find in art and nature,” “Poetry has little or no effect on me (reverse coded),” and “Sometimes when I am reading poetry or looking at a work of art, I feel a chill or wave of excitement.”

For the current study, additional validation was conducted using the Eugene Springfield Community Sample (described in our supplementary materials). Based on item correlations in that sample, all items included in our FFI openness scale had a correlation with BFAS openness of .30 or greater and this correlation with openness was at least .15 greater than the correlation with intellect. Further, there was a very strong positive correlation (approaching unity) between latent variables indicated by the four items of the FFI openness aspect scale and BFAS openness items (r = 1.0, p < .001), while the latent correlation between the FFI openness aspect scale and BFAS Intellect (r = .41, p = < .001) was significantly smaller (z = 47.1, p < .001). Nonetheless, to assuage concerns regarding use of an ad hoc shortened scale, we also repeated all analyses with the full NEO-FFI openness scale, which yielded results substantively identical to our main findings, likely due to the higher degree of representation of openness compared to Intellect in the FFI. As per the suggestion of a reviewer, Neuroticism and Conscientiousness items from the FFI were used in discriminant validity analyses.

Achenbach Self-Report (ASR; Achenbach, 2009).

Participants were administered the ASR, an instrument used to assess psychopathology. Each item uses a three-point Likert scale. In the current study, only Psychoticism items were used, as the broader thought problems scale from which they were taken includes items related to obsessiveness and self-injury. Items included “I hear sounds or voices that other people think aren’t there,” “I see things that other people think aren’t there,” “I do things that other people think are strange,” and “I have thoughts that other people would think are strange.”

Sample 2

Big Five Aspect Scales (BFAS; DeYoung et al., 2007).

The BFAS consists of 100 items that use a five-point Likert scale. The questionnaire is based on the five-factor model and breaks down each of the factors into two aspects. In the current study, the openness aspect scale was used. For latent variable modeling, items were broken into four parcels, using the first four items to create two parcels of two items each and the remaining six items to create two parcels of three items each. The Neuroticism and Conscientiousness items from the BFAS were used in discriminant validity analyses.

Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Tellegen & Waller, 2008).

Participants completed 34 MPQ items that form the absorption subscale. The full name of the construct measured is “openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences” (Tellegen & Atkinson, 1974), which is a good representation of the shared variance of openness and Psychoticism (DeYoung et al., 2016). Each item used a five-point Likert scale.

Personality Inventory for the DSM-5 (PID-5; Krueger et al., 2012).

The PID-5 is a questionnaire that includes 220 items rated on a four-point Likert scale. This inventory is used to assess symptoms of personality disorder in the alternative model from Section III of DSM-5. The PID-5 includes 25 facet scales that reflect five higher-order dimensions: Negative Affect, Detachment, Psychoticism, Antagonism, and Disinhibition. For the current study, the eccentricity, perceptual dysregulation, and unusual beliefs and experiences facet scales (from the broader Psychoticism domain) were used.

Short Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (O-LIFE; Mason et al., 2005).

The O-LIFE is a multidimensional measure that assesses positive, negative, and disorganized schizotypy, as well as nonconformity. Each item uses a true or false response. In the current study, we used only a sum score for the Unusual Experiences subscale.

Intelligence Measures

Sample 1

Intelligence was assessed using the NIH Toolbox Picture Vocabulary and List Sorting tests, as well as the Penn Matrix Test (PMAT). In the Picture Vocabulary test, participants selected which picture from a selection set most closely matched the meaning of a presented word. For the List Sorting test, participants were required to remember and sort a list of items. In the PMAT, participants completed a set of visual patterns. The NIH Toolbox measures of intelligence have shown a high degree of reliability and validity, as indexed by test-retest-reliability and associations with gold-standard measures of intelligence (Heaton et al., 2014).

Sample 2

Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale (Wechsler, 2008).

IQ was measured using four subtests of the WAIS-IV: Block Design, Matrix Reasoning, Vocabulary, and Similarities. These are the four subtests recommended by Wechsler as a brief but accurate estimate of full-scale IQ.

Behavioral Apophenia Measures (Figure 1)

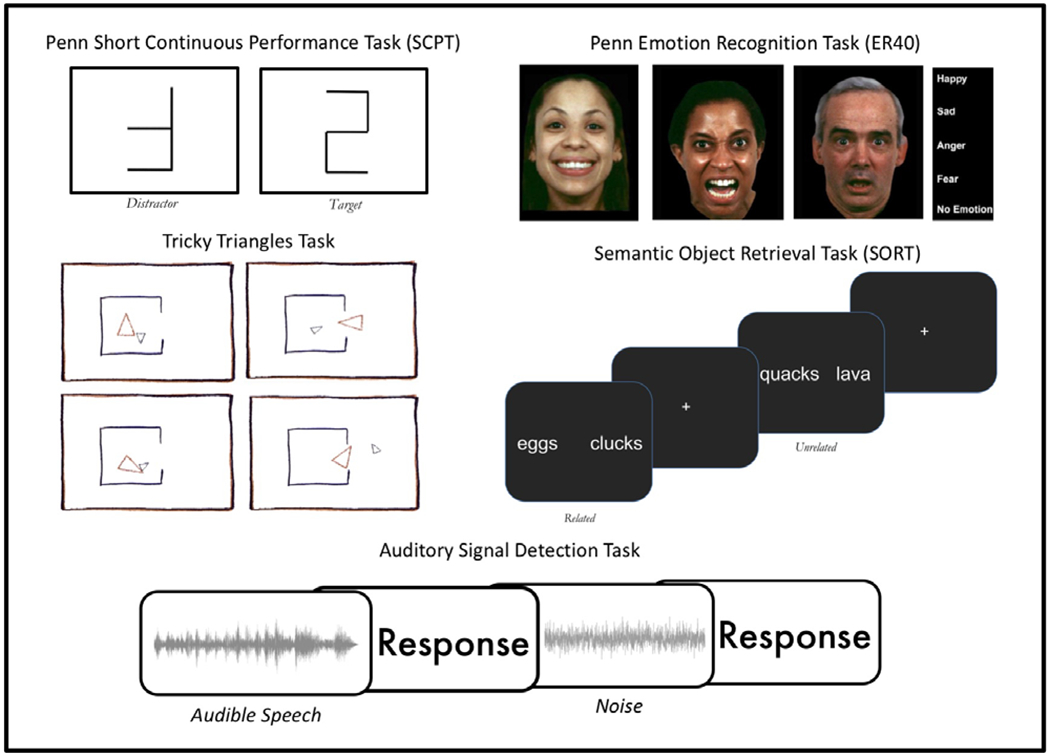

Figure 1.

Behavioral apophenia tasks

Sample 1

Tricky Triangles Task (Abell et al., 2000).

Participants were presented a series of computerized animations of shapes interacting either randomly or socially. Participants indicated whether each was random or social. The social condition included a variety of interaction types, such as seducing, coaxing, and mocking. The random condition included shapes that were drifting, bouncing, or moving in other ways that did not imply social interaction. Each participant was presented 5 random and 5 social animations, with intermixed presentation order. False positives were operationalized as random trials labeled social. False negatives were operationalized as social trials labeled random.

Penn Short Continuous Performance Task(Gur et al., 2010).

Participants were presented a series of sets of vertical and horizontal lines that either formed a target letter/digit or a distractor. Participants indicated whether each stimulus was a target or distractor. Items were presented at a rate of one per second, with 300ms viewing time per stimulus. Thirty-six targets were presented randomly among a total of 360 items. False positives were operationalized as distractors labeled targets. False negatives were operationalized as targets labeled distractors.

Penn Emotion Recognition Task (Gur et al., 2001).

Participants were presented a series of 40 faces and asked to identify what emotion each was expressing. Emotion options included Happy, Sad, Anger, Fear, and No Emotion. For each emotion, eight faces were presented. False positives were operationalized as No Emotion trials labeled either Happy, Sad, Anger, or Fear. False negatives were operationalized as total number of incorrect responses across the Happy, Sad, Anger, and Fear trials.

Sample 2

Semantic Object Retrieval Task(Assaf et al., 2009).

Participants were presented a series of 92 word-pairs that were either related or unrelated. Participants indicated whether the two words were related. Examples of related items included Popcorn and Theatre. Examples of unrelated items included Books and Kernel. False positives were operationalized as unrelated items labeled related. False negatives were operationalized as related items labeled unrelated.

Auditory Signal Detection Task (Galdos et al., 2010).

Participants were asked to indicate whether speech was present, in a series of auditory stimuli, presented in four conditions: 1) white noise only, 2) barely audible speech masked with white noise, 3) audible speech masked with white noise, and 4) speech only. Volume of trials was consistent among participants. False positives were operationalized as white-noise-only trials labeled as having speech present. False negatives were operationalized as speech trials labeled noise.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for self-report, intelligence, and false negative and false positive rates. Variables with a skew > 2.0 were logarithmically transformed to approximate normality. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was then used to assess relations among latent factors. Using raw false positive and false negative variables for each task, apophenia variables were created for each task by residualizing false positive scores by regressing them on false negative scores, resulting in variables representing unique variance of false positive tendencies for each task. This eliminates the potential confound that poor performance on a task is likely to involve both false positives and false negatives (indeed, the two types of error tended to be positively correlated within each task; Tables 2 and 3). Similar variables were created to represent unique variance in false negatives.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations among Sample 1 Measures

| O-1 | O-2 | O-3 | O-4 | P-1 | P-2 | P-3 | P-4 | PMAT | Vocab | List | ToM FP | SPCPT FP | Emo FP | ToM FN | SPCPT FN | Emo FN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| O-2 | .18 | 1.0 | |||||||||||||||

| O-3 | .14 | .40 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||

| O-4 | .12 | .49 | .67 | 1.0 | |||||||||||||

| P-1 | .02 | .05 | .06 | .07 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||

| P-2 | .02 | .02 | .06 | .07 | .48 | 1.0 | |||||||||||

| P-3 | .08 | .11 | .12 | .16 | .18 | .15 | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| P-4 | .12 | .15 | .12 | .16 | .16 | .18 | .61 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| PMAT | .14 | .13 | −.02 | .01 | −.04 | −.07 | −.01 | .05 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Vocab | .23 | .19 | .02 | .04 | −.08 | −.10 | −.05 | .02 | .47 | 1.0 | |||||||

| List | .11 | .10 | −.04 | −.03 | .00 | −.05 | −.04 | .02 | .37 | .34 | 1.0 | ||||||

| ToM FP | −.01 | .01 | .07 | .06 | .14 | .08 | .07 | .08 | −.09 | −.10 | −.06 | 1.0 | |||||

| SPCPT FP | .00 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .07 | .08 | .08 | .09 | −.21 | −.17 | −.15 | .06 | 1.0 | ||||

| Emo FP | .04 | .04 | .09 | .09 | .01 | .00 | .08 | .05 | −.12 | −.02 | −.10 | .06 | .07 | 1.0 | |||

| ToM FN | −.10 | −.09 | .01 | −.01 | −.03 | .03 | −.01 | −.02 | −.23 | −.30 | −.14 | .07 | .10 | .02 | 1.0 | ||

| SPCPT FN | −.07 | .01 | .03 | .05 | .03 | .03 | .07 | .00 | −.19 | −.20 | −.14 | .00 | .19 | .09 | .09 | 1.0 | |

| Emo FN | −.07 | −.12 | −.02 | −.03 | .02 | −.02 | .03 | .00 | −.17 | −.18 | −.10 | .04 | .08 | −.04 | .10 | .05 | 1.0 |

Notes. Correlations with absolute value > .05 are significant at a two-tailed alpha value of .05. O 1-4 = Openness NEO-FFI items 1 through 4, P1-4 = Achenbach Psychoticism items 1 through 4, PMAT = Penn Matrix Test, Vocab = Picture Vocabulary Test, List = List Sorting Test, ToM FP = Theory of Mind Task False Positives, SPCPT FP = Short Penn Continuous Performance Task False Positives, Emo FP = Emotion Recognition Task False Positives, ToM FN = Theory of Mind Task False Negatives, SPCPT FN = Short Penn Continuous Performance Task False Negatives, Emo FN = Emotion Recognition Task False Negatives

Table 3.

Pearson correlations among Sample 2 Measures

| Eccentric | Unusual | Perceptual | O-LIFE Pos | MPQ Abs | BFAS-O 1 | BFAS-O 2 | BFAS-O 3 | BFAS-O 4 | Semantic FP | Auditory FP | Semantic FN | Auditory FN | Vocab | Similarity | Matrix | Block Design | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eccentric | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Unusual | .60 | 1.0 | |||||||||||||||

| Perceptual | .66 | .74 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||

| OLIFE Pos | .48 | .56 | .67 | 1.0 | |||||||||||||

| MPQ-Abs | .65 | .74 | .79 | .61 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||

| BFAS-O 1 | .07 | .04 | .08 | .10 | .27 | 1.0 | |||||||||||

| BFAS-O 2 | .13 | .10 | .17 | .12 | .36 | .43 | 1.0 | ||||||||||

| BFAS-O 3 | .16 | .21 | .18 | .23 | .32 | .57 | .41 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| BFAS-O 4 | .13 | .20 | .10 | .19 | .29 | .30 | .34 | .35 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Semantic FP | .07 | .15 | .14 | .20 | .13 | .11 | .03 | .04 | .02 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Auditory FP | .04 | .05 | .01 | .14 | .08 | .05 | .08 | .00 | −.09 | .10 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Semantic FN | −.19 | −.04 | −.13 | −.10 | −.10 | −.17 | −.05 | −.12 | −.18 | .04 | .13 | 1.0 | |||||

| Auditory FN | .08 | .18 | .18 | .13 | .06 | −.07 | −.04 | −.02 | −.11 | .13 | −.03 | .15 | 1.0 | ||||

| Vocabulary | .18 | .03 | .12 | .08 | .18 | .20 | .12 | .23 | .19 | −.07 | .01 | −.24 | −.25 | 1.0 | |||

| Similarities | .19 | .10 | .18 | .07 | .24 | .22 | .22 | .14 | .27 | −.08 | −.04 | −.13 | −.12 | .45 | 1.0 | ||

| Matrix | .04 | .03 | −.06 | .07 | .04 | .00 | .10 | .06 | .13 | −.02 | .05 | −.09 | −.22 | .17 | .11 | 1.0 | |

| Block Design | .08 | .11 | .05 | −.05 | .10 | .19 | .10 | .05 | .16 | −.07 | .01 | −.29 | −.17 | .25 | .18 | .20 | 1.0 |

Notes. Correlations with absolute value > .13 are significant at a two-tailed alpha value of .05. Eccentric, Unusual, Perceptual = PID-5 Psychoticism sub-scales, O-LIFE Pos = Adjusted Positive Schizotypy Scale from the O-LIFE, MPQ-Abs = Absorption scale from the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire, BFAS-O 1-4 = Item parcels one to four for BFAS Openness, FP = Raw false positive rates, FN = Raw false negative rates

For Sample 1, the corresponding items or tasks were allowed to load onto latent variables for Psychoticism, Openness, Apophenia, and Intelligence. Because two Psychoticism items from the ASR were strongly semantically related, both entailing that others find the target “strange,” an a priori decision was made to allow their residuals to correlate. If they were not allowed to correlate, model fit decreased significantly (Δχ2 = 265.1, p < .001). For Sample 2, scale scores were used as indicators for Psychoticism and Openness, and, in models including both Psychoticism and Openness, MPQ absorption was added as a manifest indicator with cross-loadings from both Psychoticism and Openness. Intelligence in Sample 2 was indicated by four subtests of the WAIS, with residuals from the verbal intelligence subscales (Vocabulary and Similarities) allowed to correlate. For Sample 2, given only two tasks, factor loadings for the Apophenia factor were constrained to be equal.

Maximum likelihood estimation was used to fit all models. First, confirmatory factor analytic models were fit to examine the relations between Openness and Psychoticism. Structural equation models were then fit to examine the prediction of Apophenia by 1) Psychoticism and Intelligence, 2) Openness and Intelligence, and 3) shared variance of Openness and Psychoticism (henceforth O-P) and Intelligence. At the request of reviewers, a number of supplementary models were also fit. 1) All of the aforementioned associations were tested without controlling for Intelligence and with Intelligence-by-O-P interactions. 2) Openness and Psychoticism were examined as simultaneous predictors of Apophenia. 3) We conducted a set of discriminant validity analyses, using Neuroticism and Conscientiousness to predict our criterion variables. 4) Finally, we computed models using residualized False Negatives as criterion latent variables, as a further test of discriminant validity.

Although a strength of the present study was using multiple tasks simultaneously to assess apophenia, we nonetheless fit a set of auxiliary models to assess the relation of our questionnaire variables with apophenia scores on individual tasks. In addition to testing our hypothesis regarding the advantages of using multiple tasks to assess apophenia, this analysis also provided closer replications of several previous studies (Chen et al., 1998; Fyfe et al., 2008; Galdos et al., 2010). The same latent predictors were used as in the main models, with the observed apophenia scores (residualized false positives) from each task used, in turn, as the criterion variables.

Results

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. See Tables 2 and 3 for Pearson correlations among study measures. SEM fit statistics for our primary models are presented in Table 4. All models showed acceptable fit using the RMSEA criterion, with values ranging from .032 to .060. Factor loadings of assigned manifest variables onto their corresponding latent variables were significant, across models, albeit small in magnitude for behavioral indicators of Apophenia.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Mean (SD) | Skewness | [Minimum, Maximum] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | |||

| Openness | 2.2 (0.8) | 0.1 | [0, 4] |

| Psychoticism | 0.4 (0.9) | 2.5 | [0, 6] |

| ToM False Positives (%) | 8.5 (10.0) | 4.6 | [0, 100] |

| SPCPT False Positives | 28 (5.5) | 1.5 | [0, 28] |

| Emotion False Positives | 0.9 (1.3) | 2.0 | [0, 8] |

| ToM False Negatives (%) | 2.7 (8.3) | 3.5 | [0, 60] |

| SPCPT False Negatives | 3.6 (2.3) | 0.9 | [0, 15] |

| Emotion False Negatives | 3.6 (2.3) | 0.9 | [0, 15] |

| Matrix Test Accuracy | 16.7 (4.9) | −0.6 | [4, 24] |

| Picture Vocab | 116.6 (9.9) | 0.1 | [90.7, 153.1] |

| List Sorting | 110.9 (11.3) | 0.2 | [80.8, 144.5] |

| Sample 2 | |||

| PID-5 Eccentricity | 1.1 (0.7) | 0.2 | [0, 3] |

| PID-5 Unusual Beliefs | 0.7 (0.6) | 0.7 | [0, 2.3] |

| PID-5 Perceptual | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.6 | [0, 2.3] |

| OLIFE Positive | 9.2 (2.4) | −0.9 | [0, 12] |

| MPQ Absorption | 37.7 (18.8) | 0.3 | [4, 92] |

| BFAS Openness | 3.5 (0.5) | 0.2 | [2.1, 5] |

| Semantic False Positives | 5.7 (4.6) | 1.9 | [0, 29] |

| Auditory False Positives | 0.9 (1.9) | 3.6 | [0, 12] |

| Semantic False Negatives | 9.0 (5.0) | 1.1 | [0, 30] |

| Auditory False Negatives | 11.9 (7.3) | 1.9 | [0, 57] |

| WAIS Vocabulary Scaled | 12.3 (2.4) | −0.3 | [2, 19] |

| WAIS Similarities Scaled | 11.9 (2.4) | −0.1 | [6, 18] |

| WAIS Matrix Scaled | 10.7 (2.6) | −0.2 | [3, 18] |

| WAIS Block Design Scaled | 11.3 (3.1) | 0.0 | [4, 19] |

Table 4.

Model fit statistics

| Models | χ2 | p | RMSEA | 95% C.I. | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1 | |||||

| Model 1 (Psychoticism and 0) | 71.2 | < .001 | .050 | [.038, .062] | .960 |

| Model 2 (Psychoticism, IQ, and Apophenia) | 65.8 | < .001 | .033 | [.022, .044] | .958 |

| Model 3 (O, IQ, and Apophenia) | 144.9 | < .001 | .058 | [.049, .068] | .897 |

| Model 4 (O-Psychoticism, IQ, and Apophenia) | 228.5 | < .001 | .047 | [.040, .053] | .911 |

| Sample 2 | |||||

| Model 1 (Psychoticism and O) | 43.7 | .012 | .060 | [.028, .089] | .971 |

| Model 2 (Psychoticism, IQ, and Apophenia) | 46.4 | .048 | .046 | [.004, .074] | .961 |

| Model 3 (O, IQ, and Apophenia) | 39.0 | .183 | .032 | [.000, .064] | .961 |

| Model 4 (O-Psychoticism, IQ, and Apophenia) | 125.1 | .002 | .048 | [.029, .066] | .951 |

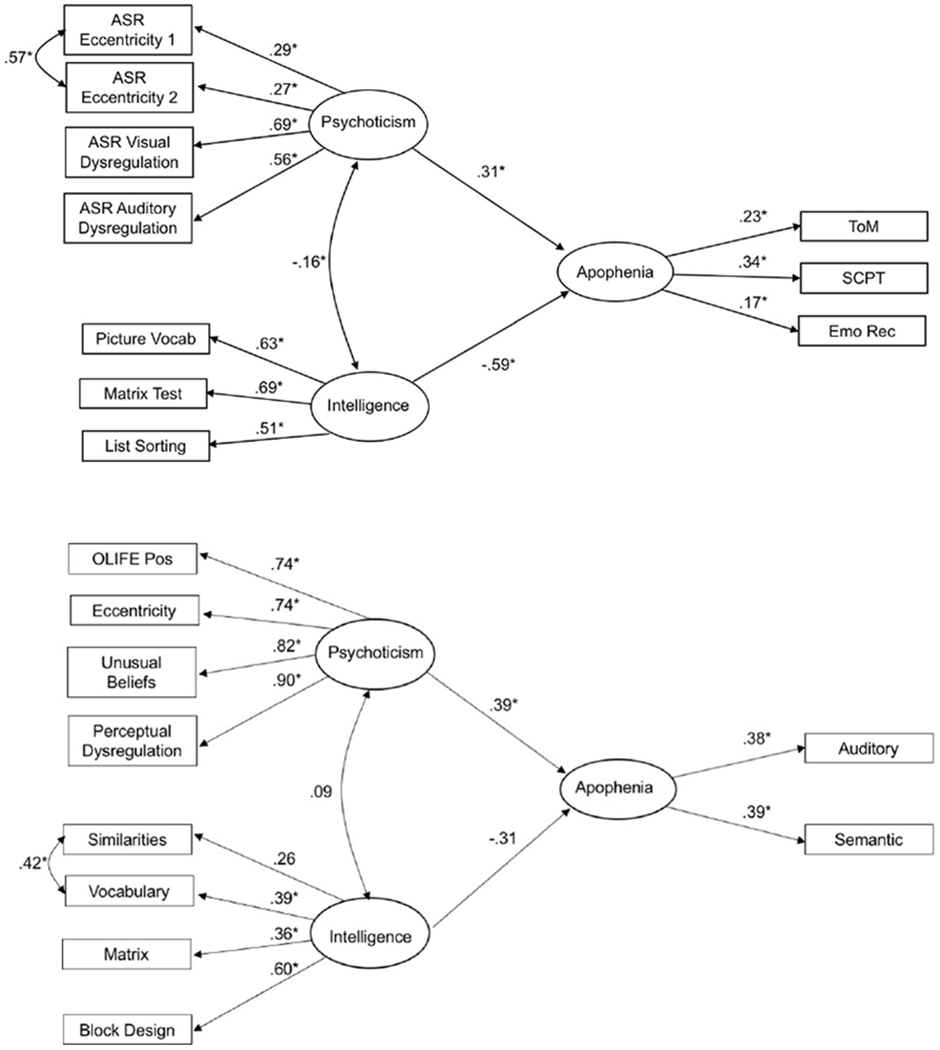

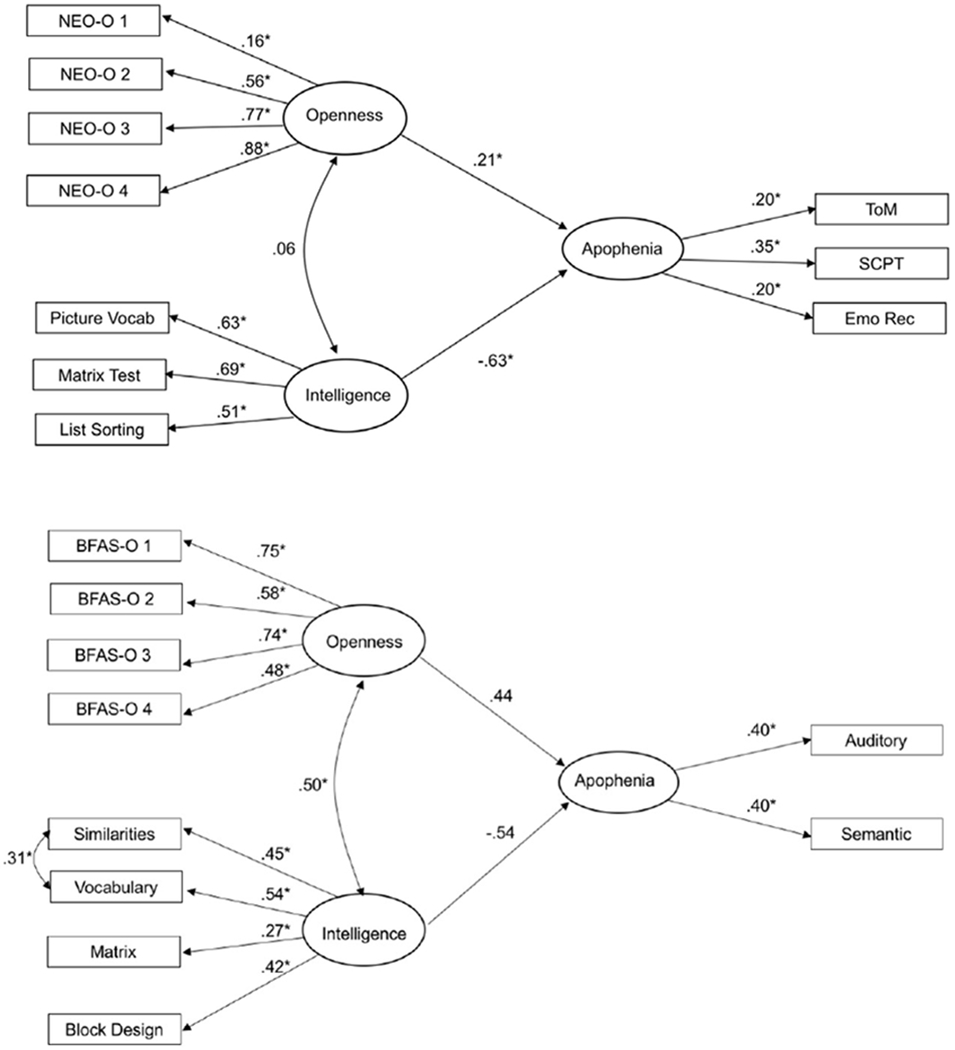

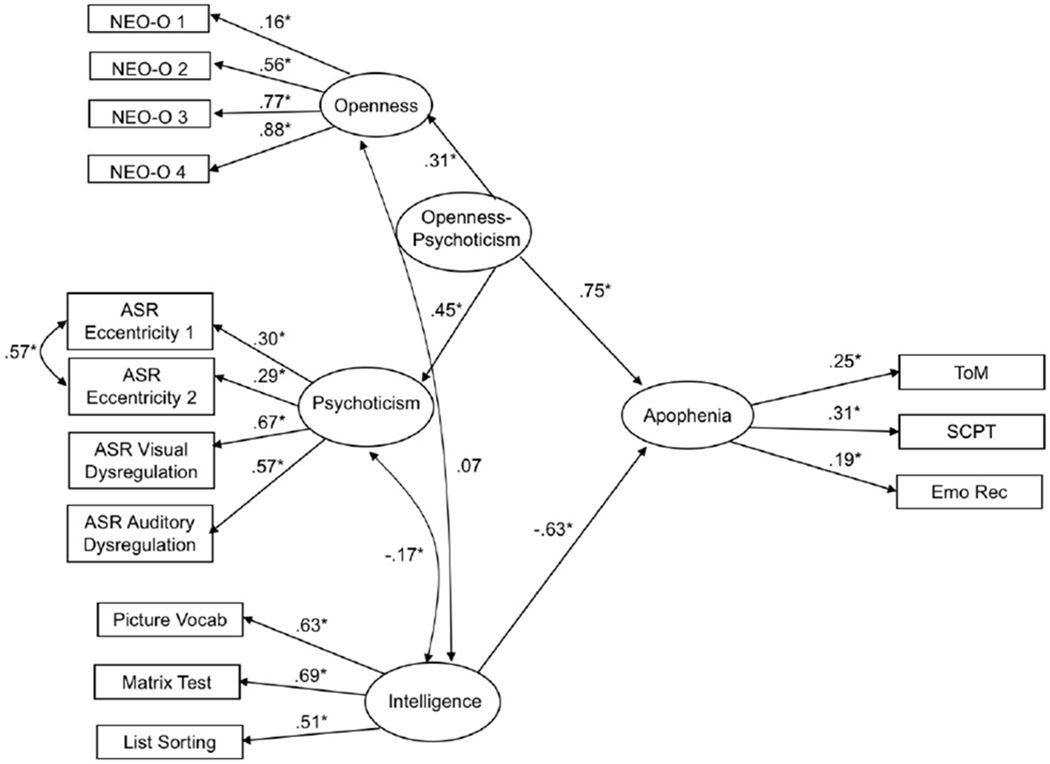

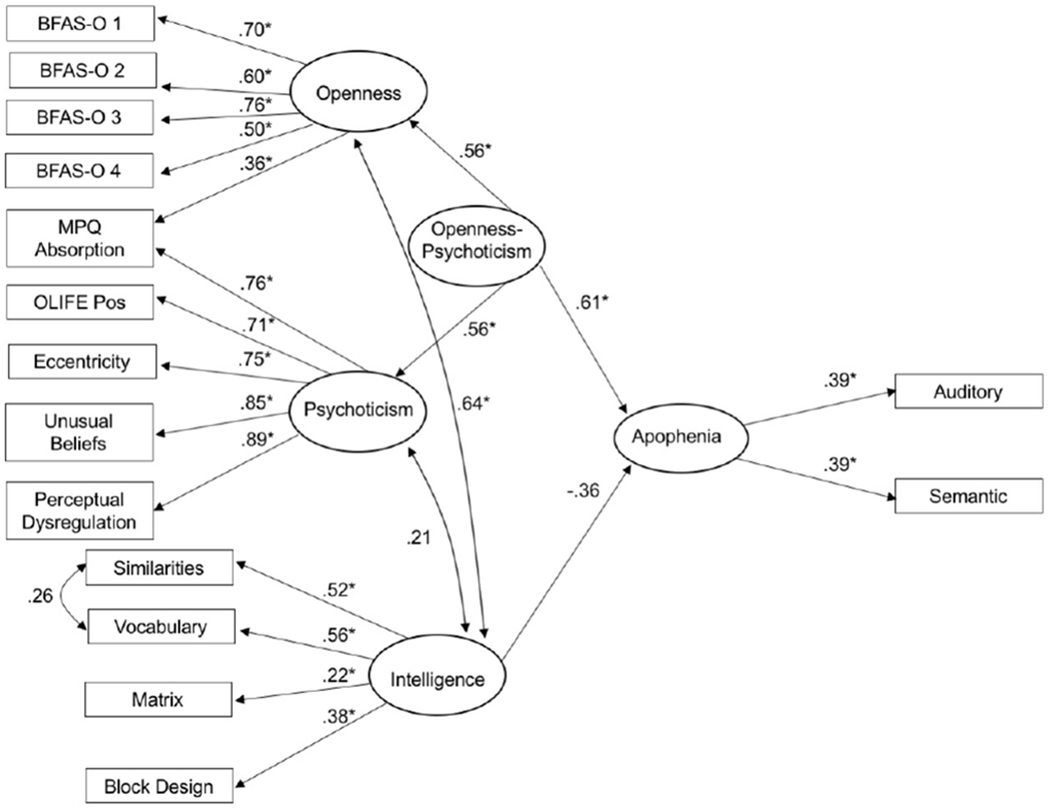

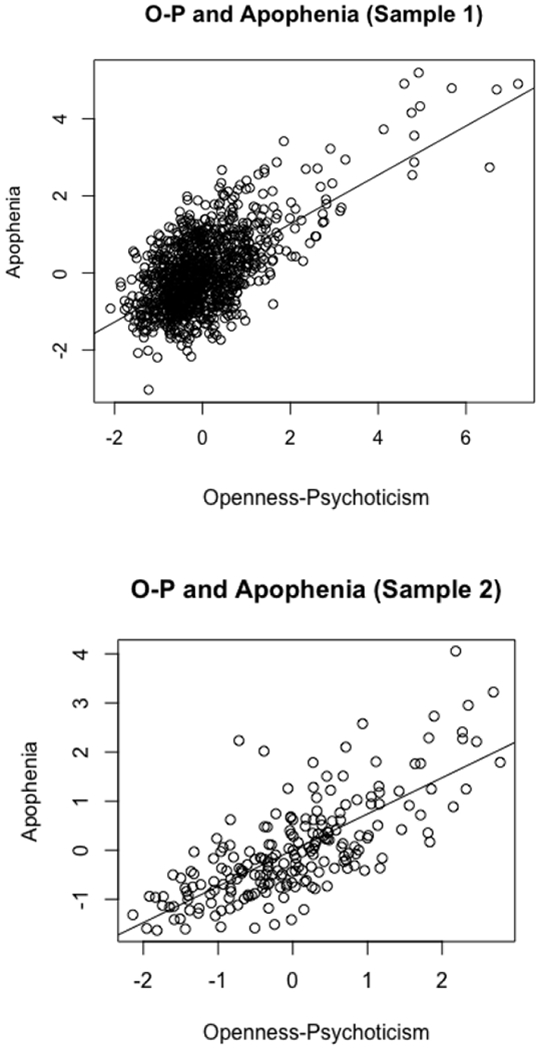

Latent Psychoticism was positively correlated with latent Openness, in Sample 1 (r = .14, p = .005) and Sample 2 (r = .31, p = .001). Latent Psychoticism was positively associated with Apophenia, in Sample 1 (Figure 2a) and Sample 2 (Figure 2b). Like Psychoticism, Openness was significantly positively associated with Apophenia in Sample 1 (Figure 3a); the path from Openness to Apophenia did not reach statistical significance in Sample 2 (Figure 3b), but magnitude of the standardized path coefficient in this model was similar to that found in Sample 1 (which had a larger N and, therefore, higher statistical power). If Openness and Psychoticism were used as simultaneous predictors (while controlling for Intelligence), their individual regression weights were somewhat diminished and only Psychoticism was a significant predictor of Apophenia in either sample (Figures S1 and S2). This pattern of suppression is consistent with the hypothesis that the shared variance of Openness and Psychoticism is associated with Apophenia. Indeed, in our final set of models, Apophenia was positively associated with O-P shared variance in Sample 1 (Figure 4) and Sample 2 (Figure 5). The relations of latent scores for O-P and Apophenia are visualized using scatterplots in Figure 6.

Figure 2.

Model of Psychoticism, Intelligence, and Apophenia — Samples 1(a) and 2(b)

Note. *p < .05

Figure 3.

Model of Openness, Intelligence, and Apophenia — Samples 1(a) and 2(b)

Note. *p < .05

Figure 4.

Model of Openness-Psychoticism, Intelligence, and Apophenia — Sample 1

Note. *p < .05

Figure 5.

Model of Openness-Psychoticism, Intelligence, and Apophenia — Sample 2

Note. *p < .05

Figure 6.

Scatterplots of latent variable relations

Associations between O-P and Apophenia remained largely consistent across samples and variables, whether or not Intelligence was controlled for (Table S1) and these associations were not present for False Negatives (Table S2). In Sample 1, Intelligence was a significant negative predictor of Apophenia, in two of three models. Intelligence strongly negatively predicted False Negatives across samples and models. Across models, findings remained substantively identical if we used raw, rather than residualized, false positive and negative variables. At the suggestion of a reviewer, we also tested for interactions between Intelligence and O-P, in predicting Apophenia (Table S1). These were mostly non-significant across variables and samples, though there was a significant interaction of Intelligence and O-P in Sample 1 (β = −.31, p < .005). Tests of discriminant validity showed that Apophenia was not predicted by Conscientiousness or Neuroticism (Table S3). Positive associations of Psychoticism, Openness, and O-P with apophenia were found for the majority of specific tasks, but relations were least robust for the auditory signal detection task (Table S4). Path coefficients from O-P variables to observed apophenia variables in the specific task models were smaller in magnitude, compared to our main models containing latent Apophenia factors.

Discussion

Findings supported our hypothesis that apophenia, as indexed by false positive rates, is positively associated with self-report measures of Psychoticism and the openness aspect of Openness/Intellect. Further, associations were specific to false positives, as Psychoticism and openness were unrelated to false negatives, so our findings do not simply represent a generalized decrement in task performance. Relations were robust and replicable in two samples, across different tasks, and, importantly, did not hold for other potentially relevant personality traits, including Neuroticism and Conscientiousness. Standardized regression coefficients for predictions of apophenia by shared O-P variance were high, ranging from .61 to .75, suggesting apophenia may be a good representation of what openness and Psychoticism have in common. Apophenia of the relatively mild sort represented by false positives on behavioral tasks likely reflects core tendencies toward pattern seeking and perceptual sensitivity, which may, in turn, result in openness to implausible patterns. Our findings suggest that apophenia may be a key cognitive process contributing to risk for psychosis. Findings also contribute to the growing body of research that identifies transdiagnostic risk factors linked to normal personality variation (DeYoung et al., 2012, 2016; Kotov et al., 2017).

The current findings replicate and unite previous empirical work. False alarms in digit identification, social triangles, white noise, and semantic association tasks have each independently been found to correlate positively with psychosis-spectrum measures (Chen et al., 1998; Fyfe et al., 2008; Galdos et al., 2010; Mohr et al., 2001). Our results extend these individual studies, suggesting that single-task indicators of apophenia may underestimate the relation between self-reported Psychoticism and behavioral apophenia. Indeed, in our present results, effect sizes for associations with individual-task false positives were much smaller in magnitude than associations with latent behavioral Apophenia. Future studies would benefit from assessing a range of behavioral apophenia tasks in order to overcome the limitations associated with task-specific variance.

Although the increased false positives associated with apophenia may seem deleterious, a tendency toward pattern seeking and perceptual sensitivity (which seems likely to underlie apophenia, openness, and Psychoticism) could have provided evolutionary advantages. Like any animal, a human being must balance false positives against false negatives in modeling regularities in its experience. Favoring false positives can aid in avoiding threat, even if it sometimes leads to an excess of caution. In contrast, a bias toward false negatives can result in failure to detect actual threats and thus constitutes a threat to survival. Further, favoring false positives may confer advantages in domains where creative pattern detection is advantageous, for example, among artists, inventors, and even psychics—precisely those populations that are high in openness (Beck & Forstmeier, 2007; Powers et al., 2016). Fitness advantages of high openness may explain the persistence of apophenia throughout the population, despite the detrimental effects of full-blown psychosis. Apophenia might therefore have had a U-shaped relation to fitness, with a moderate level being an acceptable cost for high creativity. Indeed, research suggests both openness and Psychoticism predict creativity and creative achievement, regardless of whether or not shared variance with intelligence or intellect is partialled out (Kaufman et al., 2016). Although apophenia and related traits or mechanisms (e.g., openness and pattern seeking) might be associated with certain adaptive characteristics at moderately high levels, when extreme or coupled with other risk factors (such as negative or disorganized symptoms) they may result in severe psychopathology.

Importantly, high intelligence may play a protective role when present in individuals with high openness, allowing better detection of which perceived patterns are likely to be useful rather than spurious (DeYoung et al., 2012). After a false positive error has initially occurred, intellectual deficits may contribute to an inability to separate real patterns from spurious ones, possibly leading to suspiciousness, paranoia, and delusional thinking associated with psychosis. Perhaps an optimal balance between Type I and Type II error rates occurs when an individual has high levels of intelligence as well as openness (which is typical, given that they are positively correlated), allowing high levels of creativity and cognitive exploration, without functional impairment (DeYoung, 2015). This personality profile would likely be associated with a high degree of initial Type I errors (due to high openness), paired with effective screening of these errors (due to high intelligence). In other words, some tendency toward apophenia could be advantageous when coupled with intact reality testing. Thus, individuals high in openness who have intact cognitive functioning may exhibit above average functional outcomes, despite a tendency toward apophenia, given that the combination of high levels of pattern seeking and intelligence likely facilitates the generation and application of creativity and innovative thinking.

Results from Sample 1 are consistent with this account, as apophenia was negatively correlated with intelligence. In Sample 2, however, there was no relation between intelligence and apophenia, though intelligence was strongly associated with false negative error rates. This difference might reflect either the fact that different tasks were used, or that the second sample was exclusively college students, a group with higher than average intelligence. Further research is needed to clarify the possible protective role of intelligence in relation to apophenia and the psychosis spectrum.

The current study provides insights into the measurement of apophenia using behavioral indicators, an important step in better characterizing cognitive correlates of openness and Psychoticism. Apophenia is a scientifically informative transdiagnostic feature seen across a number of disorders characterized by psychosis, including schizotypal and paranoid personality, schizophrenia, and depression and bipolar disorder with psychotic features (Chmielewski et al., 2014; Hanssen et al., 2003; Mishara et al., 2009; Narayan et al., 2013). Further elucidating the role of apophenia and pattern detection as a cognitive mechanism may prove useful for explaining variation in the tendency to make false positive errors, in populations ranging from healthy individuals to those with functionally impairing psychiatric concerns. Such an approach is in line with the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) conceptualization of psychiatric illness (Kotov et al., 2017) and with the National Institute of Mental Health’s Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) initiative, particularly its cognitive systems dimension (Cuthbert & Insel, 2013). Furthering research into the non-self-report assessment of apophenia using tasks such as those in the current study could allow for research to circumvent problems inherent to questionnaire-based research, an important step for better characterizing correlates and mechanisms underlying the psychosis spectrum, as well as psychopathology more broadly.

Limitations

Although the current study had multiple strengths, some limitations are worth noting. Despite the fact that our current measures were selected to directly mirror and conceptually replicate past research and have shown association with openness-Psychoticism in previous studies and the current sample, it is worth noting that the factor loadings of apophenia variables onto their latent factor were small in magnitude. This is likely to be an unavoidable feature of assessing false positives across a diverse range of tasks, but future work could incorporate additional or even more direct measures of apophenia, such as the Salience Attribution Test (Roiser et al., 2008).

Despite the potential of latent variables comprising multiple task or questionnaire indicators to capture truer estimates of effect size, compared to models using only individual manifest variables, this method also runs the risk of inflating effect sizes beyond their population values, when indicators share only a small portion of variance. Thus, it is important to interpret results of the current study in terms of the general trends seen across models, indicators, and traits (i.e., the consistently demonstrated, yet mild-in-magnitude relations among openness, Psychoticism, and apophenia manifest and latent variables), rather than merely focusing on effect sizes of our most comprehensive structural models.

Our measures of openness and Psychoticism were self-reported and could be usefully supplemented in future research by peer-reports or clinician ratings. Further, we cannot tell how well the current results would generalize to clinical populations, and future research should examine the roles of apophenia in those with active psychosis or at clinical high-risk. Finally, though our samples included a variety of Psychoticism and personality measures and tested apophenia across a wide variety of tasks, Sample 1 had brief questionnaire measures with relatively few items and Sample 2, though it had better questionnaire measurement, had a considerably smaller number of participants. These limitations in our current work could be addressed in the future by recruiting additional large samples with extensive, high-quality measures of Psychoticism, openness, and apophenia.

Conclusion

The current study advances research on openness, Psychoticism, and their possible underlying mechanisms. Apophenia (i.e., false positive error rate) was shown to be associated with both the openness aspect of Openness/Intellect and with Psychoticism, which is consistent with the role pattern seeking and perceptual sensitivity play in all of these traits. Apophenia, as indexed by behavioral measures of the disposition toward false positives, may provide a useful transdiagnostic construct for studying the cognitive correlates and possible mechanisms of psychosis and related phenomena, across a range of mental disorders and normal personality variation. Understanding how Psychoticism relates to normal personality variation and specific cognitive mechanisms is crucial for advancing our understanding of psychosis risk in the general population. Our current work furthers this aim and also adds to a growing body of literature demonstrating the promise of characterizing the underlying correlates and mechanisms of psychiatric features through the use of large, non-clinical samples.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded, in part, by the National Institutes of Health (Van Essen and Ugurbil; 1U54MH091657).

Author Note

Data were provided in part by the HCP, WU-Minn Consortium, funded by the National Institutes of Health (1U54MH091657) and by the McDonnell Center at Washington University. SDB was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (1348264). Study protocols conducted in Sample 1 were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Washington University (#201204036). Protocols involving Sample 2 were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (#1410S54484). This manuscript was published as a digital preprint, in efforts to facilitate open science: https://psyarxiv.com/d9wkc/. Preliminary results were presented by SDB at the International Consortium for Schizotypy Research and International Society for the Study of Individual Differences meetings, and as part of a colloquium at Ruhr University, Bochum.

References

- Abell F, Happe F, & Frith U (2000). Do triangles play tricks? Attribution of mental states to animated shapes in normal and abnormal development. Cognitive Development, 15(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM (2009). Achenbach system of empirically based assessment (ASEBA): Development, findings, theory, and applications. University of Vermont, Research Center of Children, Youth & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Assaf M, Jagannathan K, Calhoun V, Kraut M, Hart J Jr, & Pearlson G (2009). Temporal sequence of hemispheric network activation during semantic processing: a functional network connectivity analysis. Brain and cognition, 70(2), 238–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck J, & Forstmeier W (2007). Superstition and belief as inevitable by-products of an adaptive learning strategy. Human Nature, 18(1), 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blain SD, Peterman JS, & Park S (2017). Subtle cues missed: impaired perception of emotion from gait in relation to schizotypy and autism spectrum traits. Schizophrenia research, 183, 157–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blain SD, Grazioplene RG, Ma Y, & DeYoung CG (In press). Toward a neural model of the Openness-Psychoticism dimension: Functional connectivity of the default and frontoparietal control networks. Schizophrenia Bulletin. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbz103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, Sarfati Y, Bazin N, & Decety J (2003). The detection of intentional contingencies in simple animations in patients with delusions of persecution. Psychological Medicine, 33(8), 1433–1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT, & Fiske DW (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological bulletin, 56(2), 81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WJ, Hsiao CK, Hsiao LL, & Hwu HG (1998). Performance of the Continuous Performance Test among community samples. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(1), 163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski M, Bagby RM, Markon K, Ring AJ, & Ryder AG (2014). Openness to experience, intellect, schizotypal personality disorder, and Psychoticism: resolving the controversy. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28(4), 483–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, & McCrea RR (1992). Revised neo personality inventory (neo pi-r) and neo five-factor inventory (neo-ffi). Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert BN, & Insel TR (2013). Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: the seven pillars of RDoC. BMC medicine, 11(1), 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Fruyt F, De Clercq B, De Bolle M, Wille B, Markon K, & Krueger RF (2013). General and maladaptive traits in a five-factor framework for DSM-5 in a university student sample. Assessment, 20(3), 295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CG (2015). Openness/Intellect: A dimension of personality reflecting cognitive exploration. APA handbook of personality and social psychology: Personality processes and individual differences, 4, 369–399. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CG, Carey BE, Krueger RF, & Ross SR (2016). Ten aspects of the Big Five in the Personality Inventory for DSM-5. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 7(2), 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CG, Grazioplene RG, & Peterson JB (2012). From madness to genius: The Openness/Intellect trait domain as a paradoxical simplex. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CG, Quilty LC, & Peterson JB (2007). Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the Big Five. Journal of personality and social psychology, 93(5), 880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CG, Quilty LC, Peterson JB, & Gray JR (2014). Openness to experience, intellect, and cognitive ability. Journal of personality assessment, 96(1), 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe S, Williams C, Mason OJ, & Pickup GJ (2008). Apophenia, theory of mind and schizotypy: perceiving meaning and intentionality in randomness. Cortex, 44(10), 1316–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdos M, Simons C, Fernandez-Rivas A, Wichers M, Peralta C, Lataster T, … & van Os J (2010). Affectively salient meaning in random noise: a task sensitive to psychosis liability. Schizophrenia bulletin, 37(6), 1179–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant P, Balser M, Munk AJL, Linder J, & Hennig J (2014). A false-positive detection bias as a function of state and trait schizotypy in interaction with intelligence. Frontiers in psychiatry, 5, 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grazioplene RG, Chavez RS, Rustichini A, & DeYoung CG (2016). White matter correlates of psychosis-linked traits support continuity between personality and psychopathology. Journal of abnormal psychology, 125(8), 1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Ragland JD, Moberg PJ, Turner TH, Bilker WB, Kohler C, … & Gur RE (2001). Computerized Neurocognitive Scanning: I. Methodology and Validation in Healthy People. Neuropsychopharmacology, 25(5), 766–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RC, Richard J, Hughett P, Calkins ME, Macy L, Bilker WB, … & Gur RE (2010). A cognitive neuroscience-based computerized battery for efficient measurement of individual differences: standardization and initial construct validation. Journal of neuroscience methods, 187(2), 254–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen M, Peeters F, Krabbendam L, Radstake S, Verdoux H, & Van Os J (2003). How psychotic are individuals with non-psychotic disorders?. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 38(3), 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Akshoomoff N, Tulsky D, Mungas D, Weintraub S, Dikmen S, … & Gershon R (2014). Reliability and validity of composite scores from the NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery in adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 20(6), 588–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung RE, Grazioplene R, Caprihan A, Chavez RS, & Haier RJ (2010). White matter integrity, creativity, and psychopathology: disentangling constructs with diffusion tensor imaging. PloS one, 5(3), e9818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S (2003). Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: a framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. American journal of Psychiatry, 160(1), 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandaker GM, Barnett JH, White IR, & Jones PB (2011). A quantitative meta-analysis of population-based studies of premorbid intelligence and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research, 132(2-3), 220–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knezevic G, Lazarevic LB, Puric D, Bosnjak M, Teovanovic P, Petrovic B, & Opacic G (2019). Does Eysenck’s Personality Model Capture Psychosis-Proneness? Personality and Individual Differences, 143, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D, Achenbach TM, Althoff RR, Bagby RM, … & Eaton NR (2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of abnormal psychology, 126(4), 454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Derringer J, Markon KE, Watson D, & Skodol AE (2012). Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5. Psychological medicine, 42(9), 1879–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwapil TR, & Barrantes-Vidal N (2014). Schizotypy: looking back and moving forward. Schizophrenia bulletin, 41(suppl_2), S366–S373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo MT, Hinds DA, Tung JY, Franz C, Fan CC, Wang Y,… & Sanyal N (2017). Genome-wide analyses for personality traits identify six genomic loci and show correlations with psychiatric disorders .Nature Genetics, 49, 152–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason O, Linney Y, & Claridge G (2005). Short scales for measuring schizotypy. Schizophrenia research, 75(2-3), 293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick MD, Harrison BR, Park S, Bennetto L, & Tadin D (2013). A strong interactive link between sensory discriminations and intelligence. Current Biology, 23(11), 1013–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mier D, & Kirsch P (2015). Social-cognitive deficits in schizophrenia In Social Behavior from Rodents to Humans (pp. 397–409). Springer, Cham. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishara AL (2009). Klaus Conrad (1905–1961): delusional mood, psychosis, and beginning schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 36(1), 9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr C, Graves RE, Gianotti LR, Pizzagalli D, & Brugger P (2001). Loose but normal: a semantic association study. Journal of psycholingnistic research, 30(5), 475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan AJ, Allen TA, Cullen KR, & Klimes-Dougan B (2013). Disturbances in reality testing as markers of risk in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a systematic review from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Bipolar disorders, 15(1), 723–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2017). Any Mental Illness Among Adults. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/any-mental-illness-ami-among-adults.shtml

- Nosek BA, & Smyth FL (2007). A multitrait-multimethod validation of the implicit association test. Experimental psychology, 54(1), 14–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, & Holzman PS (1992). Schizophrenics show spatial working memory deficits. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49(12), 975–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, & McTigue K (1997). Working memory and the syndromes of schizotypal personality. Schizophrenia research, 26(2-3), 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont RL, Sherman MF, Sherman NC, Dy-Liacco GS, & Williams JEG (2009). Using the five-factor model to identify a new personality disorder domain: the case for experiential permeability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(6), 1245–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers AR III, Kelley MS, & Corlett PR (2016). Varieties of voice-hearing: psychics and the psychosis continuum. Schizophrenia bulletin, 43(1), 84–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross SR, DeYoung CG (2018). Scoring the 10 factors of the Big Five Aspect Scales from the NEO PI-R. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Smeland OB, Wang Y, Lo MT, Li W, Frei O, Witoelar A, … & Chen CH (2017). Identification of genetic loci shared between schizophrenia and the Big Five personality traits. Scientific Reports, 7, 2222. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02346-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Griffin SA, & Samuel DB (2017). Capturing the dsm-5 alternative personality disorder model traits in the five-factor model’s nomological net. Journal of Personality, 85(2), 220–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Samuel DB, Pahlen S, & Krueger RF (2015). DSM-5 alternative personality disorder model traits as maladaptive extreme variants of the five-factor model: An item-response theory analysis. Journal of abnormal psychology, 124(2), 343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, & Waller NG (2008). Exploring personality through test construction: Development of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. The SAGE handbook of personality theory and assessment, 2, 261–292. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, & Atkinson G (1974). Openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences (“absorption”), a trait related to hypnotic susceptibility. Journal of abnormal psychology, 83(3), 268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomporowski PD, & Simpson RG (1990). Sustained attention and intelligence. Intelligence, 14(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2008). Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Fourth Edition (WAIS–IV). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS, & Pincus AL (1989). Conceptions of personality disorders and dimensions of personality. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1(4), 305. [Google Scholar]

- Wright ZE, Pahlen S, & Krueger RF (2017). Genetic and environmental influences on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-(DSM–5) maladaptive personality traits and their connections with normative personality traits. Journal of abnormal psychology, 126(4), 416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammit S, Allebeck P, David AS, Dalman C, Hemmingsson T, Lundberg I, & Lewis G (2004). A longitudinal study of premorbid IQ score and risk of developing schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, and other nonaffective psychoses. Archives of general psychiatry, 61(4), 354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.