Stigma is a mark of disgrace associated with a circumstance, quality, or person. Its roots are deepened in complex dimensions of prior intrapersonal and interpersonal experiences [1]. Before effective treatments were available, people living with hepatitis C (HCV) infection felt judged by having a disease associated with illicit drug use. The patient’s perceived stigma created a disincentive to address self-care needs and illness management until it was clinically too late [2].

The World Health Organization issued a target for HCV elimination (90% reduction in HCV incidence and a 65% reduction in HCV mortality) by 2030 [3]. The advent of highly effective direct-acting antiviral therapy (DAA) has spurred optimism that the elimination of HCV is a possibility with DAA scale-up. By treating and curing HCV massively, HCV transmission will be so infrequent that HCV would no longer be considered a public health threat.

People living with HIV (PLWH) historically felt stigmatized and marginalized [4–5]. Moreover, PLWH co-infected with HCV are burdened by the highest prevalence of ongoing barriers to care, such as drug and alcohol use, mental illness, and unstable housing which contributes to their poorer health outcomes [6]. In the last decade, a new epidemiologic twist was recognized: HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM) acquired HCV disproportionally higher through sexual transmission. Studies pointed out that high sexual risk behaviors are important determinants to the HCV epidemic among MSM [7]. Unintentionally, this message might have created a negative stereotype of HIV-infected MSM, which might ostracize some of them.

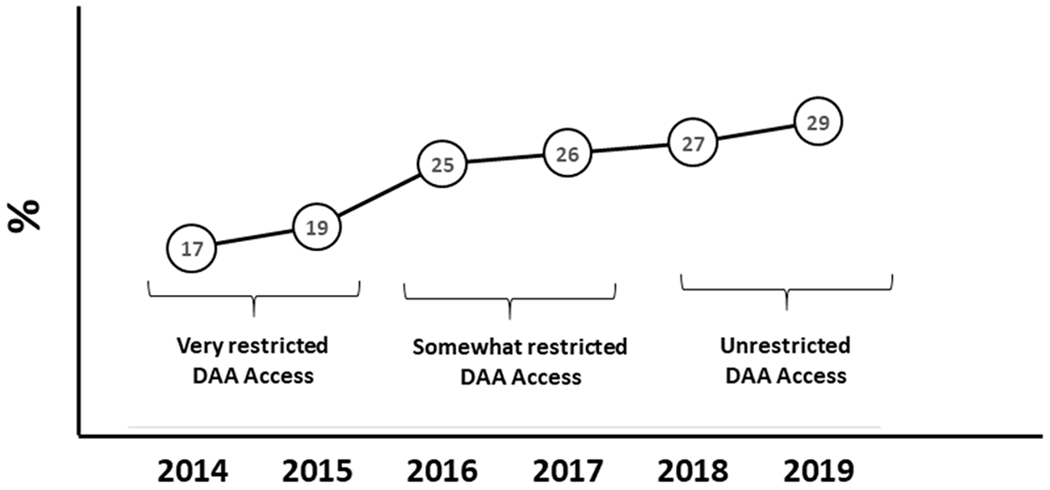

Although significant progress in decreasing population-level of HCV viremia has occurred since the DAA introduction in many settings with unrestricted DAA access, there seems to be a plateau of 10-15% of PLWH who despite knowing they have HCV do no seek DAA treatment [8]. The lack of HCV engagement in care phenomena seems counterintuitive, as insurance restrictions decrease, the proportion of patient HCV No Shows continues to increase. For example, in the United States of America in the state of California, DAA access evolved from a period of extreme insurance restrictions to a recent era of unrestricted DAA access among PLWH. Nevertheless, the proportion of No Show appointments for first HCV intake appointments in our HIV hepatitis C coinfection clinic that operates within the same premises of our HIV clinic increased from 17% in 2014 to 29% in 2019 (figure). This counterintuitive phenomenon of slow DAA treatment uptake is often attributed to a combination of patient’s ongoing barriers to care, sub-optimal hepatitis C disease knowledge or low health literacy [9]. I wonder if we are overlooking the impact of HIV providers’ role in ameliorating the patient’s perceived stigma and resulting mistrust on the medical system.

Figure.

Proportion of first hepatitis C No Show appointments at the Hepatitis C Co-infection clinic at the University of California, San Diego

DAA = Direct-acting antivirals

Often PLWH in need of DAA show up after multiple prior No Show appointments. We need to treat every interaction with a PLWH seeking DAA treatment as a unique opportunity to build a trustworthy horizontal relationship with our patients. Not only is the essence of what HIV providers who treat HCV important but the form matters, too. For instance, preventing and counseling regarding HCV reinfection is critical, but has to be done in a balanced way. There is need to document in the medical record patients’ understanding of behaviors that increase risk of HCV reinfection, but we need to be sensitive and do it in a non-judgmental manner to avoid the unintended consequence of our discussion could be perceived by some patients as ongoing microaggressions and disincentive them to come back to HCV care. Unlike the interferon times, the irony of the DAA era is that the effective, well-tolerated, and short-courses of DAA provide limited time-points to contribute with enhancing PLWH prospective engagement in care. Increasing awareness among medical providers of the importance of patient’s stigma and resulting mistrust might help us to facilitate our patient’s HCV retention in care. Nowadays, to be cure of HCV, a patient needs to get the pill, but also take the pill. Without building on our patient’s trust, creating a stigma-free environment, many would not seek the pill, or even if they get it, may not take it consistently.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported in part by NoCo Grant funded by Gilead Sciences (IN-US-334-4481), the Clinical Investigation Core of the University of California San Diego Center for AIDS Research [AI036214], and the Pacific AIDS Education and Training Center (PAETC). The funders had no role in study design, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References:

- 1.Butt G Stigma in the context of hepatitis C: concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:712–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butt G, Paterson BL, McGuinness LK. Living With the Stigma of Hepatitis C. West J Nurs Res. 2008; 30:204–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Report May 2016. Combating hepatitis B and C to reach elimination by 2030. Available at: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hep-elimination-by-2030-brief/en/ Accessed 15 August 2019.

- 4.King MB, AIDS on the death certificate: the final stigma. BMJ. 1989;298:734–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mimiaga MJ, OʼCleirigh C, Biello KB, et al. The effect of psychosocial syndemic production on 4-year HIV incidence and risk behavior in a large cohort of sexually active men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 68:329–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagan H, Jordan AE, Neurer J, Cleland CM. Incidence of sexually transmitted hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2015;29:2335–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boerekamps A, van den Berk GE, Lauw FN, et al. Declining Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Incidence in Dutch Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Positive Men Who Have Sex With Men After Unrestricted Access to HCV Therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 17; 66:1360–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cachay ER, Hill L, Torriani F, Ballard C, Grelotti D, Aquino A, Christopher Mathews W. Predictors of Missed Hepatitis C Intake Appointments and Failure to Establish Hepatitis C Care Among Patients Living With HIV. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(7):ofy173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]