Abstract

Background

It is disputed whether recurrent episodes of wheeze in preschool-aged children comprise a distinct asthma phenotype.

Objective

We sought to prospectively assess airflow limitation and airway inflammation in children 4 to 6 years old with episodic virus-induced wheeze.

Methods

Ninety-three children 4 to 6 years old with a history of mild, virus-induced episodes of wheeze who were able to perform acceptable fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (Feno) maneuvers and spirometry (with forced expiratory time ≥0.5 seconds) were followed prospectively. Lung function and Feno values were measured every 6 weeks (baseline) within the first 48 hours of an acute wheezing episode (day 0) and 10 and 30 days later. Symptom scores and peak flow measurement were recorded daily.

Results

Forty-three children experienced a wheezing episode. At day 0, Feno values were significantly increased, whereas forced expiratory volume at 0.5 seconds (FEV0.5) significantly decreased compared with baseline (16 ppb [interquartile range {IQR}, 13-20 ppb] vs 9 ppb IQR, 7-11 ppb] and 0.84 L [IQR, 0.75-0.99 L] vs 0.99 L [IQR, 0.9-1.07 L], respectively; both P < .001). Airflow limitation at day 0 was reversible after bronchodilation. FEV0.5 and Feno values were significantly associated with each other and with lower and upper respiratory tract symptoms when assessed longitudinally but not cross-sectionally at all time points independently of atopy. Feno and FEV0.5 values returned to baseline levels within 10 days.

Conclusions

Mild episodes of wheeze in preschoolers are characterized by enhanced airway inflammation, reversible airflow limitation, and asthma-related symptoms. Feno values increase significantly during the first 48 hours and return to personal baseline within 10 days from the initiation of the episode. Longitudinal follow-up suggests that symptoms, inflammation, and lung function correlate well in this phenotype of asthma.

Key words: Airflow limitation, airway inflammation, spirometry, reversibility, exhaled nitric oxide, forced expiratory volume at 0.5 seconds, longitudinal study

Abbreviations used: dNTP, Deoxynucleotide triphosphates; Feno, Fraction of exhaled nitric oxide; FET, Forced expiratory time; FEV0.5, Forced expiratory volume at 0.5 seconds; iNOS, Inducible nitric oxide synthase; IQR, Interquartile range; MEFV, Maximal expiratory flow/volume; NO, Nitric oxide; PEF, Peak expiratory flow

A significant proportion of preschool-aged children experience recurrent episodes of wheeze, cough, or shortness of breath, mainly associated with viral respiratory tract infections.1 Asthma is defined as a complex disorder characterized by specific symptoms and signs, reversible airway obstruction, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and airway inflammation.2, 3, 4 The paucity of relevant evidence in the preschool age group might explain why the term “asthma” is frequently avoided and alternative approaches have been suggested.5

Airway inflammation in wheezing infants and young children has not been comprehensively studied, mainly because of ethical limitations, although there is evidence of airway remodeling quite early in life.6, 7, 8 Fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (Feno) has received considerable attention as a noninvasive marker to assess airway inflammation, diagnose asthma in preschoolers,9 or subdivide wheezers into various phenotypes.10, 11 The majority of similar studies had a cross-sectional design; however, it is well established that Feno values can be influenced by current or recent viral infections12, 13 and the use of oral or inhaled steroids.

Although challenging, spirometry is feasible in preschool children.14 Taking into account the physiology of lung function in this age group, the dynamics of a forced expiratory trial, and the fact that maximal expiratory flow/volume (MEFV) maneuvers are effort dependent, standard criteria for an acceptable and repeatable MEFV have been recommended.15 However, it has not been adequately studied whether a preschool-aged child can perform an acceptable MEFV trial during a wheezing episode and to what extent these parameters fluctuate during that episode, as well as the extent of their utility. Moreover, in toddlers and older children with asthma-related symptoms, attempts to correlate inflammation, lung function, and symptoms have most frequently been inconclusive or negative. Nevertheless, these parameters have not been assessed longitudinally and in parallel.16, 17

In this study we aimed to longitudinally evaluate and associate airway inflammation, airflow limitation, and symptoms during the course of the episodic, virus-induced wheezing disorder in steroid-naive children 4 to 6 years of age.

Methods

Study population

Children 4 to 6 years of age from the outpatient clinics of our institution given a previous diagnosis of “episodic viral wheeze” according to the European Respiratory Society Task Force5 or “virus-induced asthma” according to the Practical Allergy (PRACTALL) Consensus Report18 were invited to participate. Patients were eligible if they had been given a diagnosis for a minimum of 1 year of at least 1 mild wheezing episode in the preceding 12 months without previous need for hospital admission and, according to their medical records, need for inhaled β-agonists, inhaled corticosteroids, or montelukast. Patients receiving inhaled corticosteroids or montelukast on a regular or episodic basis were recruited after at least a 14-week wash-out period. Furthermore, children were required to be able to perform an MEFV effort with a forced expiratory time (FET) of 0.5 seconds or greater and a correct online Feno maneuver according to standard criteria.15, 19 The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all parents.

Outcomes

Symptoms, medication, and daily peak expiratory flow measurements

Symptom scores (modified from Johnston et al20), medication use, and peak expiratory flow (PEF) measurements were recorded daily by the parents on diary cards throughout the study. Upper airway symptoms in the diary cards included blocked/stuffy nose, runny nose, sneezing/itchy nose, itchy/sore/watery eyes, hoarse voice, and sore throat. Lower airway symptoms included cough during the day and during the night, wheezing/noisy breathing during the day and during the night, and cough/wheezing/noisy breathing during exercise. Each of these symptoms was scored from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (severely troublesome symptoms). Parents were advised to contact the study physician and arrange an appointment within 48 hours after the child started wheezing and having at least 1 of the lower airways symptoms, difficulty breathing, or nighttime awakening. PEF was measured daily in the morning and evening by using the electronic PEF meter PiKo-1 (nSpire Health, Longmont, Colo), which records time and date along with the PEF measurements. These records were used as an indirect way to assess compliance in filling out the diary cards. For further details, see the Methods section in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

Allergic sensitization

Levels of serum-specific IgE (ImmunoCAP; Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden) to a panel of locally relevant common aeroallergens and food allergens were measured either after the wheezing episode or at the age of 6 years for those children without a wheezing episode during the study. A patient was classified as atopic if at least 1 allergen-specific IgE was greater than 0.7 IU/mL. For further details, see the Methods section in this article's Online Repository.

Feno measurement

Airway inflammation was determined based on Feno values (in parts per billion) by using the NIOX MINO (Aerocrine, Solna, Sweden) chemiluminescence analyzer with a 10-second standard mode exhalation time (≤10 attempts per visit), according to current guidelines.19 For further details, see the Methods section in this article's Online Repository.

Spirometry

Spirometry was performed with a Jaeger MasterScope-PC spirometer (VIASYS Healthcare, Höchberg, Germany). All maneuvers were performed with the children in the standing position by using a nose clip and an incentive animation. Results were reported only if at least 2 technically acceptable curves (≤8 maneuvers per visit), as determined according to standard criteria15 and with an FET of greater than 0.5 seconds, were obtained. Forced expiratory volume at 0.5 seconds (FEV0.5), forced vital capacity, FET, and back-extrapolated volume (VBE) from the best maneuver (that with the highest sum of FEV0.5 and forced vital capacity values) was recorded. Spirometry was performed before and after bronchodilation with 400 μg of salbutamol (Aerolin; GlaxoSmithKline, Athens, Greece) delivered through a metered-dose inhaler with a spacer (Aerochamber Plus Flow Vu; Trudell Medical International, London, Ontario, Canada).

Viral identification

Nasal washes were performed with 2.5 mL of normal saline in each nostril, and viruses were identified by means of PCR, as previously described.21 For further details, see the Methods section in this article's Online Repository.

Study design

After recruitment, a baseline questionnaire including demographic characteristics and data in respect to the wheezing episodes was obtained. The children were followed up (evaluation of diary cards and new Feno and spirometric measurements) regularly every 6 weeks until they had a wheezing episode or until they reached their sixth birthday. All measurements were repeated during the first 48 hours from the beginning of an episode (day 0) and 10 (day 10) and 30 (day 30) days later. Nasal wash specimens were obtained at day 0. During the episodes, all children received 200 μg of salbutamol 4 times daily.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of at least 17 subjects would be sufficient to detect paired Feno measurement differences of at least the accuracy of the NIOX MINO, taking into account the referred precision (accuracy, ±5 ppb of measured values <50 ppb; precision, ±3 ppb of measured value <30 ppb), with at least 90% power at the 5% significance level. Because atopic status may influence Feno values, paired measurements were assessed in both atopic and nonatopic wheezers. The prevalence of sensitization in preschool-aged children with the aforementioned inclusion characteristics is expected to be approximately 50%.22 Thus at least 34 wheezers are enough to have at least 17 subjects per group. Approximately 60% of children who wheezed during the first 3 years of life are expected to cease to wheeze by the age of 6 years.22 After adjusting the number of recruited children accordingly, taking into account an additional 10% failure to perform the required tests14 or loss to follow-up, the number of children needed to be recruited was calculated to be 99.

Descriptive statistics are presented as medians (interquartile ranges [IQRs]) for nonnormally distributed continuous variables and as means ± SDs for normally distributed variables. Wilcoxon rank sum or Student t tests were used to compare binary outcomes (atopy, virus identifications, and sex) at the same time point. Wilcoxon matched-pairs rank sum or Student paired t tests were used for between-time-point comparisons of the same variable. Associations between categorical data were assessed by using the Pearson χ2 test. Analyses across these time points were performed with generalized estimating equations after adjusting for known confounders, such as height, age, and atopy.23 For these models, Feno values were log-transformed to follow the normal distribution. For the day 0 to day 30 period, all variables were treated as time dependent, except age, sex, atopy, and height. For further details, see the Methods section in this article's Online Repository.

Results

From the 98 candidate, consecutive examined children, 93 were recruited: 4 were unable to perform a correct Feno maneuver, and 1 was unable to perform spirometry with an FET of greater than 0.5 seconds. The mean age at recruitment was 4.5 ± 0.4 years. At this time point, there were no significant differences in age, sex, height, and all baseline measurements between atopic children, nonatopic children, and children completing the study without any wheezing episodes. Regular follow-up visits occurred every 40 ± 4 days. Forty-three of 93 children had at least 1 wheezing episode 0.6 ± 0.3 years after recruitment. The episodes were equally distributed among seasons, except summer, whereas the available baseline measurements at different seasons were not significantly different when assessed in an individualized manner (data not shown).

The baseline characteristics were similar between atopic and nonatopic children (Table I ). After the initial assessment at the beginning of the episode (day 0), the children were re-evaluated 10 ± 1 days (day 10) and 30 ± 3 days (day 30) later. Compliance was high for electronic PEF recordings both on regular daily measurements and during the wheezing episode (85% ± 9% and 95% ± 3%, respectively), as assessed indirectly from the PiKo-1. None of the children reported wheezing unrelated to apparent upper respiratory tract infections or lower respiratory symptoms. Four children (3 atopic) had episodes of short-lasting, self-limited mild upper respiratory tract symptoms without lower respiratory tract symptoms or wheezing.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of atopic and nonatopic children with a wheezing episode and children without a wheezing episode during the study period

| Atopic wheezers∗ (n = 25) | Nonatopic wheezers∗ (n = 18) | Children with no episode† (n = 46) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 5 ± 0.5 | 5 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.3 |

| Male sex, no. | 14 (56%) | 9 (50%) | 20 (44%) |

| Height (m) | 1.11 ± 0.07 | 1.15 ± 0.05 | 1.07 ± 0.05 |

| Atopic | 25 | 0 | 21 (46%) |

| Baseline Feno (ppb) | 10 (7-11) | 8.5 (6-10) | 9.1 (7-10) |

| Baseline FEV0.5 (L) | 0.97 (0.9-1.07) | 1 (0.92-1.07) | 0.94 (0.747-1.139) |

| Baseline FVC (L) | 1.274 ± 0.266 | 1.336 ± 0.191 | 1.141 ± 0.17 |

| Baseline PEF (L/min) | 158.1 (136.8-198.6) | 157.8 (153-177) | 151.4 (140-178.7) |

| Previously treated with bronchodilators alone‡ | 18 (72%) | 14 (77.8%) | 32 (69.6%) |

Values are presented as means ± SDs or medians (IQRs) unless otherwise reported

FVC, Forced vital capacity.

Baseline values obtained 8 weeks before the recorded wheezing episode.

Baseline values obtained at recruitment and atopic status at the age of 6 years.

The rest of the children had been treated before enrollment with inhaled corticosteroids, montelukast, or both.

Symptoms

Lower (median; day 0: 8 [IQR, 5-11], day 10: 1 [IQR, 0-2], and day 30: 0 [IQR, 0-1]) and upper (day 0: 4 [IQR, 3-7], day 10: 1 [IQR, 0-2], and day 30: 0 [IQR, 0-1]) respiratory tract symptoms did not differ between atopic and nonatopic children regarding severity at any time point. All children reported cough during exercise in the first 10 days after the acute wheezing episode.

Feno measurements

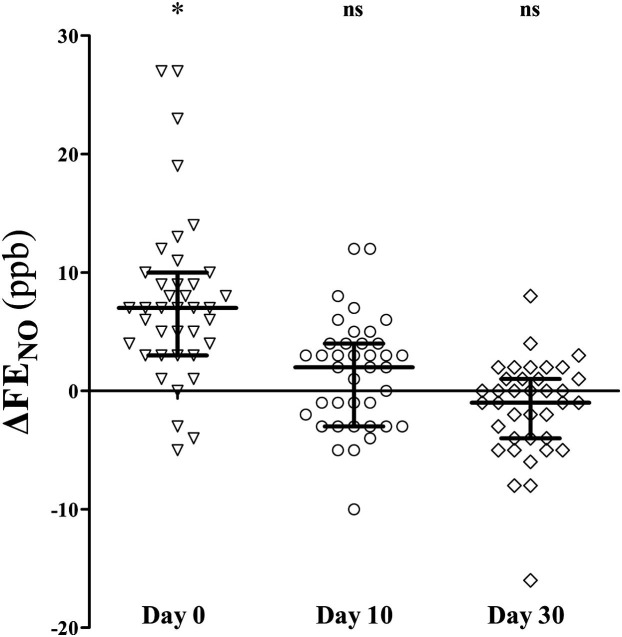

The vast majority of the children (96%) achieved a correct Feno maneuver after proper training. Baseline measurements were within the expected normal range24 both for the atopic (median at baseline: 10 ppb [IQR, 7-11 ppb] vs expected normal value: 10.7 ppb [95% CI, 8.4-13.5 ppb]) and nonatopic (8.5 ppb [IQR, 6-10 ppb] vs 7.8 ppb [95% CI, 7.1-8.5 ppb]) groups. Feno values were significantly increased during the first 48 hours of a wheezing episode compared with personal values at baseline (16 ppb [IQR, 13-20 ppb] vs 9 [IQR, 7-11 ppb], respectively; P < .001), returning to initial values within the next 10 days (10 ppb [IQR, 7-12 ppb]). Feno measurements were comparable between atopic and nonatopic wheezers at all time points (see Table E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Feno paired changes from baseline are presented in Fig 1 .

Fig 1.

Feno changes from baseline levels at the beginning of a wheezing episode (day 0) and 10 (day 10) and 30 (day 30) days after. ns, Nonsignificant. *P < .001, Wilcoxon matched-pairs rank sum test. Lines and error bars correspond to medians and IQRs.

FET

A wheezing episode did not affect the children's ability to perform a reliable and reproducible MEFV measurement. FET in the second set of MEFV trials after bronchodilation was significantly lower than FET before bronchodilation (Table II ).

Table II.

FETs at baseline and during a virus-induced wheezing episode

| FETbefore (s) |

FETafter (s) |

P value∗ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | No. of cases with FET < 1 s (%) | Median (IQR) | No. of cases with FET <1 s (%) | ||

| Baseline | 1.23 (0.89-2.08) | 17/43 (39.5%) | 1.02 (0.7-1.46) | 20/43 (46.5%) | .007 |

| Day 0 | 1.39 (0.97-2.27) | 12/43 (27.9%) | 1.29 (0.82-1.79) | 15/43 (34.9%) | .147 |

| Day 10 | 1.68 (0.96-2.62) | 13/43 (30.2%) | 1.39 (0.85-2.23) | 16/43 (37.2%) | .093 |

| Day 30 | 1.35 (0.97-2.78) | 11/43 (25.6%) | 1.2 (0.87-2.22) | 14/43 (32.6%) | .003 |

In all efforts, FETs were greater than 0.5 seconds.

Comparison of prebronchodilation (FETbefore) and postbronchodilation (FETafter) FETs based on Wilcoxon matched-pairs rank sum test.

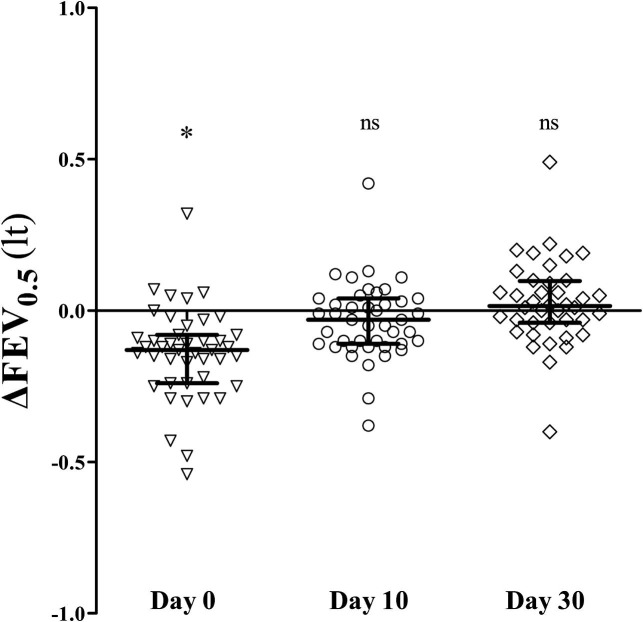

FEV0.5

Prebronchodilation FEV0.5 values decreased significantly from baseline during day 0 (median: 0.84 L [IQR, 0.75-0.99 L] vs 0.99 L [IQR, 0.9-1.07 L], P < .001) and returned to baseline within the next 10 days. Paired changes from baseline are presented in Fig 2 . At all time points, FEV0.5 values were comparable between atopic and nonatopic wheezers (see Table E2 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). Bronchodilator responses were significantly higher from baseline values only on day 0 (13.3% [IQR, 6.5% to 20.6%] vs baseline: 5.4% [IQR, 3% to 10.1%], P < .001) independently of the atopic status. Postbronchodilation FEV0.5 values at day 0 were comparable with prebronchodilation baseline values, indicating reversibility of airflow limitation (0.99 L [IQR, 0.86-1.14 L] vs 0.99 L [IQR, 0.9-1.07 L], respectively; P = .621). Moreover, prebronchodilation baseline FEV0.5 values were comparable, with the predicted values calculated from Nystad et al14 (0.99 L [IQR, 0.9-1.07 L] vs 1.04 L [IQR, 0.93-1.13 L], respectively; P = .100).

Fig 2.

Prebronchodilation FEV0.5 changes from baseline levels at the beginning of a wheezing episode (day 0) and 10 (day 30) and 30 (day 30) days after. ns, Nonsignificant. *P < .001, Wilcoxon matched-pairs rank sum test. Lines and error bars correspond to medians and IQRs.

Virus identification

Nasal wash samples from day 0 were available in 35 of 43 children. At least 1 virus was identified in 26 (74.3%) of these 35 children. Rhinovirus was the most prevalent identified in 22 (62.5%) samples, followed by adenovirus in 6 (17.1%) samples, parainfluenza in 2 (5.7%) samples, coronavirus in 2 (5.7%) samples, and influenza in 1 (2.9%) sample. Coinfection of rhinovirus with adenovirus was noted in 3 cases, with parainfluenza virus in 1 case, and with coronavirus in another case. No differences in virus identification with regard to atopic status were observed (P = .758). Feno and FEV0.5 values did not differ significantly between virus-positive and virus-negative cases (data not shown).

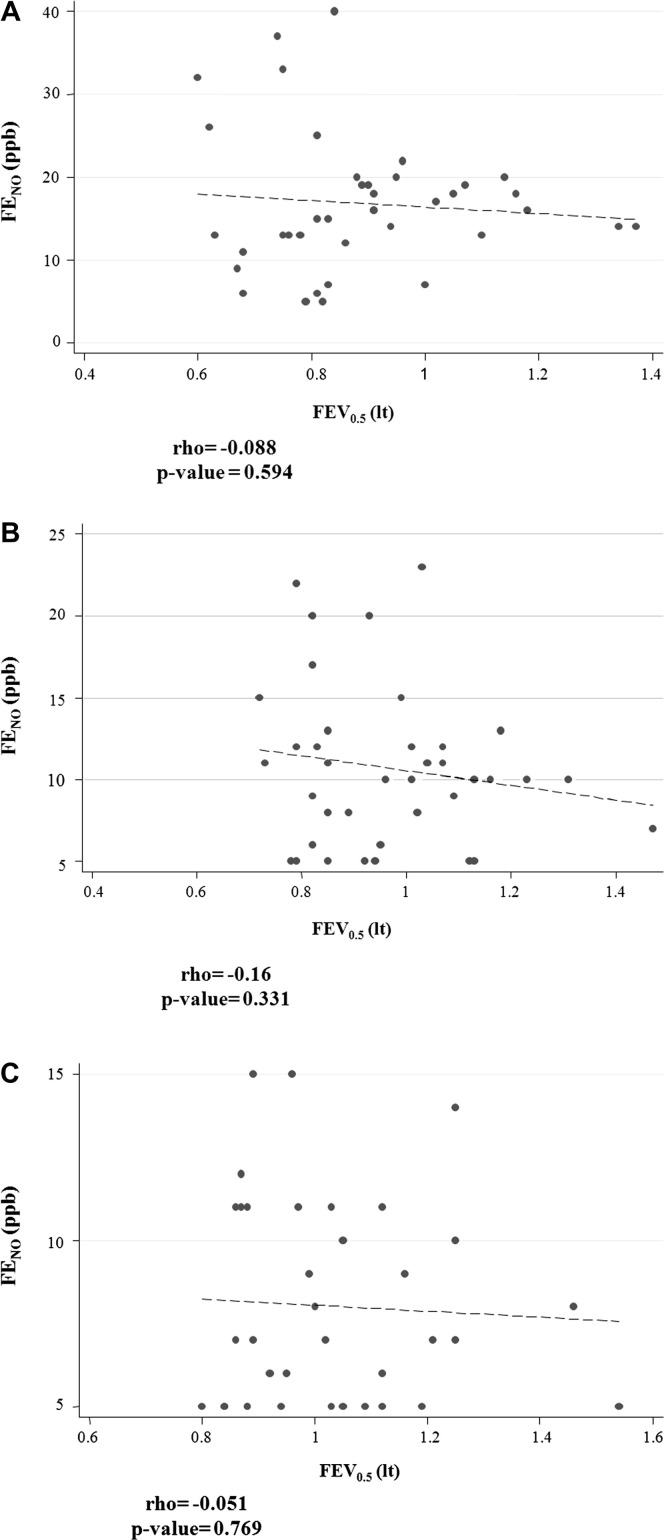

Time-dependent outcomes

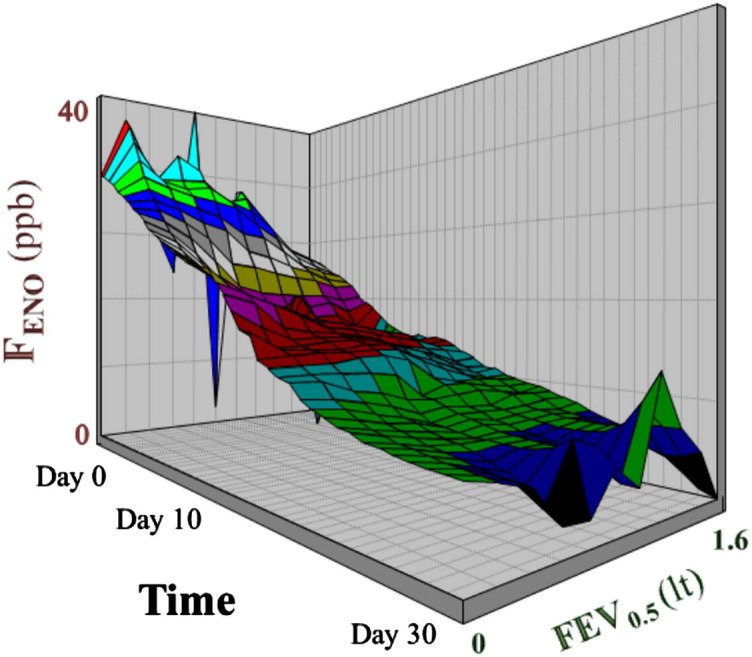

All pairwise cross-sectional correlations at days 0, 10, and 30 between Feno values, prebronchodilation FEV0.5 values, and symptoms were weak and nonsignificant (see Fig E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org). However, when assessed longitudinally from day 0 to day 30, prebronchodilation FEV0.5 and Feno values were significantly associated both with each other and with symptoms (Fig 3 and Table III, Table IV ).

Fig 3.

Longitudinal associations (for numeric details, see Table III, Table IV) between Feno and prebronchodilation FEV0.5 values presented graphically from the beginning until 30 days after an acute wheezing episode. The different colors correspond to different Feno values and have been used to better distinguish the 3-dimensional surface plot.

Table III.

Generalized estimating equation models assessing fluctuation of Feno values during a wheezing episode

| Independent variable | Feno (ppb),∗ unadjusted model |

Feno (ppb),∗ age- and height-adjusted model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates | SE | P value | Estimates | SE | P value | |

| Age | 0.056 | 0.078 | .470 | — | — | — |

| Height | −0.0004 | 0.007 | .949 | — | — | — |

| Sex | −0.138 | 0.103 | .180 | — | — | — |

| Atopy | 0.041 | 0.105 | .700 | — | — | — |

| FEV0.5 | −0.546 | 0.277 | .049 | −0.803 | 0.325 | .013 |

| Lower respiratory tract symptoms | 0.055 | 0.006 | <.001 | 0.055 | 0.006 | <.001 |

| Upper respiratory tract symptoms | 0.060 | 0.012 | <.001 | 0.060 | 0.012 | <.001 |

Data are presented as estimates ± SEs. Sex, age, and height were considered time independent. Data are estimates of the coefficients for the models with the dependent variable of either Feno or FEV0.5 at the 3 time points of a wheezing episode based on a generalized estimating equations model. Feno values were log-transformed to follow the normal distribution.

Log transformed.

Table IV.

Generalized estimating equation models assessing fluctuation of FEV0.5 values during a wheezing episode

| Independent variable | Prebronchodilation FEV0.5 (L), unadjusted model |

Prebronchodilation FEV0.5 (L), age- and height-adjusted model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates | SE | P value | Estimates | SE | P value | |

| Age | 0.142 | 0.035 | <.001 | — | — | — |

| Height | 0.016 | 0.301 | <.001 | — | — | — |

| Sex | −0.046 | 0.054 | .399 | — | — | — |

| Atopy | 0.002 | 0.055 | .971 | — | — | — |

| Feno∗ | −0.091 | 0.018 | <.001 | −0.091 | 0.018 | <.001 |

| Lower respiratory tract symptoms | −0.014 | 0.002 | <.001 | −0.014 | 0.002 | <.001 |

| Upper respiratory tract symptoms | −0.019 | 0.003 | <.001 | −0.019 | 0.003 | <.001 |

Data are presented as estimates ± SEs. Sex, age, and height were considered time independent. Data are estimates of the coefficients for the models with the dependent variable of either Feno or FEV0.5 at the 3 time points of a wheezing episode based on a generalized estimating equations model. Feno values were log-transformed to follow the normal distribution.

Log transformed.

Discussion

As shown in this study, an acute episode of viral wheeze or virus-induced asthma in children 4 to 6 year of age is characterized by airway inflammation (defined by means of increased Feno values), airflow limitation (decreased FEV0.5 values), and bronchodilator reversibility, as well as symptoms (noisy breathing, cough, and shortness of breath), signs (wheezing and tachypnea), need for and response to inhaled β2-agonists, and evidence of airway bronchial hyperresponsiveness (indicated by cough during exercise). Evidently, this entity shares the core characteristics of asthma with other phenotypes independently of atopic status.

Interestingly, cross-sectional correlations between Feno, prebronchodilation FEV0.5, and symptoms were nonsignificant. Similar to other studies with older children,25, 26 these were all significantly associated when assessed longitudinally. The fact that cross-sectional associations were not significant in contrast to longitudinal evaluations in our study highlights the need to prospectively assess time-dependent parameters. Furthermore, Feno and FEV0.5 fluctuations, at least in this age group of children, should be individualized to have diagnostic value and help in the monitoring of such episodes.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that follows the natural history of a virus-induced asthmatic episode to demonstrate that inflammation, lung function, and symptoms are significantly correlated when assessed in parallel. Moreover, Feno measurements and spirometry have been demonstrated to be feasible during a wheezing episode.

Studies have shown increased bronchial epithelial inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression during in vivo infection with rhinovirus13 and in vitro infection with influenza A27 and respiratory syncytial virus.28 Moreover, epithelial iNOS expression represents the major determinant of Feno values,29 whereas iNOS activity accounts for up to 95% of the measured Feno value.30 Additionally, a small proportion, up to 7.5%, of Feno originates from the oropharynx and oral cavity.31 Collectively, taking into consideration the existing nonenzymatic formation of nitric oxide (NO) from nitrite in saliva,32 the observation that NO synthase–mediated NO formation is of at least the same magnitude as the formation of NO from nitrite,33 and the fact that examined children in our cohort refrained from nitrate-rich foods before measurements,34 the contribution of oropharyngeal exhaled NO in measured Feno values is expected to be less than 5%. This proportion corresponds to less than 1 ppb of the Feno measured at all time points, suggesting a negligible contribution of the oropharyngeal mucosal NO in these measurements.

It is well established that Feno values increase after experimental rhinovirus,35 influenza virus,36 or presumably upper respiratory tract infections12 in asthmatic and nonasthmatic subjects. This is not the case for nasal NO of subjects with disease limited to the upper respiratory tract,37 suggesting that NO production is mainly associated with lower respiratory tract pathology. Moreover, it has been shown that rhinovirus is able to infect the bronchial epithelium and induce local inflammation, probably leading to asthma exacerbations in predisposed subjects.38 Because airway NO is considered to play a pivotal role in antiviral defense,39 Feno changes measured during these episodes conceivably reflect host-defense response to virus-induced airway inflammation. Feno measurements in our study returned to baseline values within 10 days, probably reflecting basal NO production rather than disease activity, as previously suggested in a more persistent population.10 It is not clear whether virus-induced Feno increase can be downregulated by corticosteroids, but it seems unlikely because steroids, especially for rhinovirus infection, do not seem to modulate virus-induced interferon responses of the bronchial epithelium.40 This might explain why, at least in this phenotype and age group, Feno does not seem to perform well in predicting inhaled corticosteroid response41 and why corticosteroid therapy does not seem to have any disease-modifying effect on the progression of episodic wheezing.42, 43 However, it is not known whether this acute, short-lasting inflammatory response, especially if it relapses multiple times after new respiratory tract viral infections, could predispose to or explain the transition from an unclear and uncertain asthmatic status to a definite chronic inflammatory process characterizing asthma. Further studies are needed to elucidate this issue, and some promising approaches have already been initiated (www.predicta.eu).

All children but 1 had FETs of greater than 0.5 seconds. Young children have relatively large airway sizes compared with the absolute lung volumes that are to be emptied,44 resulting in the fastest rate of emptying and therefore explaining the shorter duration of forced expiration. Spirometric maneuvers and measurements were not affected during the episode in respect to the quality and duration of the effort. All comparisons between consecutive prebronchodilation forced expiratory efforts (based on FETs) at different time points were not significantly different. Interestingly, waiting for bronchodilation response to perform a second MEFV trial appeared to shorten FET duration. This might be an effect of bronchodilation per se or might be effort related.15 Almost half of the examined children at all time points measured did not achieve an FET of 1 second at both prebronchodilation and postbronchodilation spirometric efforts.

In respect to spirometry, the FEV0.5 value, as an indicator of bronchial obstruction, decreased significantly during wheezing episodes and spontaneously returned to baseline within 10 days. Therefore, abnormal pulmonary function is present only during episodes, as shown previously.11 Moreover, mean bronchodilation responses were significantly higher at the beginning of the episode in comparison with baseline values. Statistically significant bronchodilation responses were observed even at baseline measurements, although with a small nonsignificant magnitude, which is consistent with another study.11 Such an observation might imply a higher bronchomotor tone, which is in keeping with the prolonged postviral nonspecific hyperresponsiveness that has been shown in this type of wheezers.45

Viral identification was similar to previously published data.20 Analogously, peak upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms did not differ significantly with regard to atopy, a finding that has been described before in studies comparing healthy subjects and those with mild asthma.46 Likewise, atopic status was not proved to play a significant role in Feno or prebronchodilation FEV0.5 fluctuations.

A major strength of this study is the steroid-naive cohort that has been used, which makes results robust and easier to interpret. However, a weakness of the study is the lack of a healthy control group because of ethical considerations about salbutamol administration in healthy children.47 However, we tried to overcome this by using accepted prediction equations for lung function testing,14 normal Feno values,24 and individual baseline measurements to compare and adjust for the outcomes of interest.

In conclusion, this study clearly demonstrates that inflammation, airway limitation, and symptoms are significantly associated in a longitudinal manner throughout an acute wheezing episode in 4- to 6-year-old children with virus-induced wheezing episodes. Feno values increase significantly during the first 48 hours of the episode and return to baseline “personal normal” values within 10 days. On the basis of the FET expected in this age group, FEV0.5 seems to be the most appropriate parameter to assess airflow limitation and bronchodilation response both at baseline and during a wheezing episode. Both Feno and FEV0.5 are also promising in correctly identifying and monitoring patients with (virus-induced) airway obstruction at the acute phase of a wheezing episode. Longitudinal assessment of time-dependent lung function and airway inflammation parameters appears to be superior to cross-sectional analyses, while at the same time it highlights the need for an individualized approach in patients with complex diseases, such as asthma.

Key messages.

-

•

Mild virus-induced wheezing episodes in 4- to 6-year-old children are characterized by airflow limitation and airway inflammation, sharing these characteristics with other asthma phenotypes.

-

•

Feno values increase during the first 48 hours of such an episode and return to personal baseline values within 10 days without anti-inflammatory treatment and independently of atopic status.

-

•

Feno and FEV0.5 values, when assessed longitudinally and in an individualized manner, might help when monitoring such episodes.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and their parents for their participation. We also thank Andrew Ross for English editing.

Footnotes

Supported by resources of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece (Special Account for Research Grants/ELKE Account).

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: N. G. Papadopoulos has consultant arrangements with Abbott; has received grants from Nestlé, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Deviblis (EBT); has received payment for lectures from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Allergopharma, Uriach, and GlaxoSmithKline; and has received payment for development of educational presentations from Merck Sharp & Dohme and Uriach. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Methods

Study population

Premature children (<36 weeks' gestation) with congenital anomalies or facial, thoracic, or mediastinal disorders; hospitalization for any respiratory tract infection; or past history of pneumonia/tuberculosis/interstitial lung disease or need for mechanical ventilation before enrollment were excluded.

Outcomes

Allergic sensitization

All patients were tested for specific IgE (ImmunoCAP, Phadia) to the following aeroallergens: Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, cat dander, dog epithelium, mixed grass pollens, Cladosporium species, Aspergillus species, Alternaria species, olive, cypress and wall pellitory pollen, and food allergens: hen's egg, cow's milk, and nut mix (fx1).

Feno measurement

According to the guidelines and the NIOX MINO specifications, for a correct Feno measurement, a single breath sample was instantly analyzed after the subject inhaled to total lung capacity through an NO-scrubbing filter to avoid contamination with ambient NO. All exhalations were performed at an exhalation pressure of 10 to 20 cm H2O to maintain a fixed flow rate of 50 ± 5 mL/s. The pressure is necessary to ensure closure of the soft palate to avoid contamination of the Feno with gas from the nasopharynx,E1 where NO concentrations are very high.E2 In addition, the targeted constant flow exhalation rate consists of a washout phase followed by an NO plateau. It is generally considered that this plateau represents NO derived primarily from the lower respiratory tract.E3 Cloud pictures and sound cues of a built-in flowmeter and a light on the top of the device were enough incentives to help young children to blow at the right pressure during the exhalation. The first valid measurement was recorded.E4 Children should not have eaten or drunk for at least 2 hours before and avoided nitrate rich meals for at least 20 hours before measurements.E5 Directions were given according to these dietary recommendations for regular visits. Exacerbation visits were arranged according to the last meal or snack.

Spirometry

Children were encouraged to keep their mouths on the mouthpiece at the end of the expiration to avoid FET overestimation.E6

Symptoms

Symptoms were rated for severity, frequency, or both as follows: 0, none/never; 1, mild/rarely; 2, moderate/sometimes; 3, quite severe/often; and 4, very severe/very often.

Upper airway symptoms in the diary cards included (1) blocked/stuffy nose, (2) runny nose, (3) sneezing/itchy nose, (4) itchy/sore/watery eyes, (5) hoarse voice, and (6) sore throat. Lower airways symptoms included (1) cough during the day, (2) cough during the night, (3) wheezing/noisy breathing during the day, (4) wheezing/noisy breathing during the night, and (5) cough/wheezing/noisy breathing during exercise. Upper respiratory scores ranged from 0 to 24, and lower respiratory scores ranged from 0 to 20. Two additional questions were answered with yes or no: difficulty breathing/shortness of breath and nighttime awakening caused by breathing difficulties.

The questionnaires with the aforementioned scoring system were sensitive enough to correctly identify wheezing episodes.

Nasal wash specimens and viral identification

Total RNA from nasopharyngeal washes was obtained by using phenol-chloroform extraction. By using 50 μL of sample and diluting it in RNAse/DNAse-free water (1:4), we extracted 20 μL of total RNA, which was kept at −80°C. Reverse transcription was performed in 2 rounds in 8 μL of total RNA by using Superscript III and RNAse OUT, and from 50 μL of nasopharyngeal wash, 20 μL of cDNA was produced.

Rhinovirus PCR was performed in cDNA samples by adding 6 μL of cDNA in 44 μL of Master Mix containing 10× PCR Buffer, 50 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), 10 μmol/L primers (OL26, 5′ GCA CTT CTG TTT CCC C 3′; OL27, 5′ CGG ACA CCC AAA GTA G 3′), and 5 U/μL Platinum Taq. The total reaction volume was 50 μL, and after the agarose gel electrophoresis, the product was detected at 380 bp.

Adenovirus PCR was performed in cDNA samples by adding 4 μL of cDNA in 46 μL of Master Mix containing 10× PCR Buffer, 50 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L dNTPs, 10 μmol/L primers (Ad1/5, 5′ GCC GAG AAG GGC GTG CGC AGG TA 3′; Ad2, 5′ TAC GCC AAC TCC GCC CAC GCG CT 3′), and 5 U/μL Platinum Taq. The total reaction volume was 50 μL, and after the agarose gel electrophoresis, the product was at 140 bp.

Parainfluenza virus (type 1-3) PCR was performed in cDNA samples by adding 2 μL of cDNA in a 48-μL Master Mix containing 10× PCR Buffer, 50 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L dNTPs, 10 μmol/L primers (PF1/01, 5′ CAG AAT TAA TCA GAC AAG AAG T 3′; PF1/02, 5′ AGG ATA CAT ATC TGA ATT TAA G 3′; PF2/01, 5′ GGA TAA TAC AAC AAT CTG CTG 3′; PF2/02, 5′ CAC AGG TTA TGT TGG GAT G 3′; PF3/01, 5′ CTC GAG GTT GTC AGG ATA TAG 3′; and PF3/02, 5′ CTT TGG GAG TTG AAC ACA GTT 3′), and 5 U/μL Platinum Taq. The total reaction volume was 50 μL, and the PCR products were detected at 430, 370, and 180 bp.

Human metapneumovirus (MPV) PCR was performed in cDNA samples by adding 2 μL in a 48-μL Master Mix containing 10× PCR Buffer, 50 mmol/L MgCl2, and 10 mmol/L dNTPs (MPV-NF, 5′ AGG CCC TCA GCA CCA GAC A 3′; MPV-NR, 5′ TTG ACC GGC CCC ATA AGC 3′). The total reaction volume was 50 μL, and the PCR product was detected at 318 bp.

Influenza virus A/B PCR was performed in cDNA samples by adding 2 μL of cDNA in a 48-μL Master Mix containing 10× PCR Buffer, 50 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 μmol/L primers (AH1A, 5′ CAG ATG CAG ACA CAA TAT GT 3′; AH1FII, 5′ AAA CCG GCA ATG GCT CCA AA 3′; AH3A, 5′ CAG ATT GAA GTG ACT AAT GC 3′; A3DII, 5′ GTT TCT CTG GTA CAT TCC GC 3′; BHAA, 5′ GTG ACT GGT GTG ATA CCA CT 3′; BHADII, 5′ TGT TTT CAC CCA TAT TGG GC 3′; AH1B, 5′ ATA GGC TAC CAT GCG AAC AA 3′; AHIEII, 5′ CTT AGT CCT GTA ACC ATC CT 3′; AH3B, 5′ AGC AAA GCT TTC AGC AAC TG 3′; AH3CII, 5′ GCT TCC ATT TGG AGT GAT GC 3′; BHAB, 5′ CAT TTT GCA AAT CTC AAA GG 3′; and BHACII, 5′ CAT TTT GCA AAT CTC AAA GG 3′), and 5 U/μL Platinum Taq. The total reaction volume was 50 μL, and the PCR products were at 600, 1000, and 800 bp.

Study design

Eligible children were instructed by the study physician to perform accepted Feno measurements and spirometry. All tests were performed at the lung function laboratory at the Allergy Research Center of the University of Athens. Children were followed up regularly every 6 weeks. In case of multiple nonsymptomatic follow-up visits, measurements recorded 6 weeks before an episode were used as baseline measurements (Feno and spirometry performed in that order).

The instrument selected and saved the best result from 3 tests performed in a row. To avoid anti-inflammatory treatment-induced bias, episodes uncontrolled with salbutamol monotherapy were, per design, excluded from the analysis, whereas follow-up was continued until a new eligible episode occurred after a wash-out period of at least 14 weeks.

Statistical analysis

Analyses across the time points of interest were performed with generalized estimating equations to examine the association of Feno and FEV0.5 values and symptoms by using the Gaussian family of distribution and an unstructured correlation structure.E7 The distribution of the variables of interest was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. All reported P values were based on 2-sided tests and compared with a significance level of 5%. STATA 9.1 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, Tex) and NCSS/PASS 2004 (Kaysville, Utah) software were used for all statistical calculations and plots.

Fig E1.

Scatter plot of Feno and FEV0.5 values A, Beginning of the wheezing episode (day 0). B, Ten days after (day 10). C, Thirty days after (day 30).

Table E1.

Feno values at baseline and at the beginning of a wheezing episode (day 0), 10 days (day 10) and 30 days after (day 30): pairwise comparisons

| Atopic subjects | Nonatopic subjects | P value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (ppb) | 10 (7-11) | 8.5 (6-10) | .342 |

| Day 0 (ppb) | 16 (12-20) | 15.5 (13-19.5) | .977 |

| P value∗ (baseline vs day 0) | <.001 | .001 | |

| Day 10 (ppb) | 11 (7-13) | 9.5 (7-11.5) | .381 |

| P value∗ (baseline vs day 10) | .069 | .363 | |

| P value∗ (day 0 vs day 10) | <.001 | .002 | |

| Day 30 (ppb) | 7 (5-11) | 7 (5-9) | .376 |

| P value∗ (baseline vs day 30) | .192 | .218 | |

| P value∗ (day 0 vs day 30) | <.001 | <.001 | |

| P value∗ (day 10 vs day 30) | .061 | .064 |

Values are presented as medians (IQRs).

P values based on the Wilcoxon matched-pairs rank sum test.

Comparison between atopic and nonatopic subjects: P values based on the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Table E2.

Prebronchodilation FEV0.5 values at baseline and at the beginning of a wheezing episode (day 0), 10 days (day 30) and 30 days after (day 30): pairwise comparisons

| Atopic subjects | Nonatopic subjects | P value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (L) | 0.97 (0.9-1.07) | 1 (0.92-1.07) | .712 |

| Day 0 (L) | 0.88 (0.76-1) | 0.815 (0.73-0.91) | .279 |

| P value∗ (baseline vs day 0) | .001 | <.001 | |

| Day 10 (L) | 0.93 (0.82-1.07) | 0.97 (0.91-1.04) | .605 |

| P value∗ (baseline vs day 10) | .128 | .112 | |

| P value∗ (day 0 vs day 10) | .003 | <.001 | |

| Day 30 (L) | 0.955 (0.87-1.155) | 1.025 (0.965-1.105) | .307 |

| P value∗ (baseline vs day 30) | .898 | .133 | |

| P value∗ (day 0 vs day 30) | <.001 | <.001 | |

| P value∗ (day 10 vs day 30) | .003 | .001 |

Values are presented as medians (IQRs).

P values based on the Wilcoxon matched-pairs rank sum test.

Comparison between atopic and nonatopic subjects: P values based on the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

References

- 1.Jackson D.J., Gangnon R.E., Evans M.D., Roberg K.A., Anderson E.L., Pappas T.E. Wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in early life predict asthma development in high-risk children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:667–672. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) report. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention revised December 2011. Available at: http://www.ginasthma.org/Guidelines/guidelines-resources.html. Accessed September 2012.

- 3.British guideline on the management of asthma. Thorax. 2008;63(suppl 4):iv1–121. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.097741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, Third Expert Panel on the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma . National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US); Bethesda (MD): 2007 Aug. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7232/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brand P.L., Baraldi E., Bisgaard H., Boner A.L., Castro-Rodriguez J.A., Custovic A. Definition, assessment and treatment of wheezing disorders in preschool children: an evidence-based approach. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1096–1110. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00002108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saglani S., Malmstrom K., Pelkonen A.S., Malmberg L.P., Lindahl H., Kajosaari M. Airway remodeling and inflammation in symptomatic infants with reversible airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:722–727. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200410-1404OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saito J., Harris W.T., Gelfond J., Noah T.L., Leigh M.W., Johnson R. Physiologic, bronchoscopic, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid findings in young children with recurrent wheeze and cough. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41:709–719. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saglani S., Payne D.N., Zhu J., Wang Z., Nicholson A.G., Bush A. Early detection of airway wall remodeling and eosinophilic inflammation in preschool wheezers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:858–864. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-212OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malmberg L.P., Pelkonen A.S., Haahtela T., Turpeinen M. Exhaled nitric oxide rather than lung function distinguishes preschool children with probable asthma. Thorax. 2003;58:494–499. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.6.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moeller A., Diefenbacher C., Lehmann A., Rochat M., Brooks-Wildhaber J., Hall G.L. Exhaled nitric oxide distinguishes between subgroups of preschool children with respiratory symptoms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:705–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonnappa S., Bastardo C.M., Wade A., Saglani S., McKenzie S.A., Bush A. Symptom-pattern phenotype and pulmonary function in preschool wheezers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.018. e1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kharitonov S.A., Yates D., Barnes P.J. Increased nitric oxide in exhaled air of normal human subjects with upper respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:295–297. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08020295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanders S.P., Siekierski E.S., Richards S.M., Porter J.D., Imani F., Proud D. Rhinovirus infection induces expression of type 2 nitric oxide synthase in human respiratory epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:235–243. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nystad W., Samuelsen S.O., Nafstad P., Edvardsen E., Stensrud T., Jaakkola J.J. Feasibility of measuring lung function in preschool children. Thorax. 2002;57:1021–1027. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.12.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beydon N., Davis S.D., Lombardi E., Allen J.L., Arets H.G., Aurora P. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: pulmonary function testing in preschool children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1304–1345. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-642ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Covar R.A., Szefler S.J., Martin R.J., Sundstrom D.A., Silkoff P.E., Murphy J. Relations between exhaled nitric oxide and measures of disease activity among children with mild-to-moderate asthma. J Pediatr. 2003;142:469–475. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Debley J.S., Stamey D.C., Cochrane E.S., Gama K.L., Redding G.J. Exhaled nitric oxide, lung function, and exacerbations in wheezy infants and toddlers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1228–1234.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacharier L.B., Boner A., Carlsen K.H., Eigenmann P.A., Frischer T., Gotz M. Diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood: a PRACTALL consensus report. Allergy. 2008;63:5–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ATS/ERS recommendations for standardized procedures for the online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide, 2005. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:912–930. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-710ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston S.L., Pattemore P.K., Sanderson G., Smith S., Lampe F., Josephs L. Community study of role of viral infections in exacerbations of asthma in 9-11 year old children. BMJ. 1995;310:1225–1229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6989.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spyridaki I.S., Christodoulou I., de Beer L., Hovland V., Kurowski M., Olszewska-Ziaber A. Comparison of four nasal sampling methods for the detection of viral pathogens by RT-PCR-A GA(2)LEN project. J Virol Methods. 2009;156:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez F.D., Wright A.L., Taussig L.M., Holberg C.J., Halonen M., Morgan W.J. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. The Group Health Medical Associates. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:133–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franklin P.J., Taplin R., Stick S.M. A community study of exhaled nitric oxide in healthy children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:69–73. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9804134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brussee J.E., Smit H.A., Kerkhof M., Koopman L.P., Wijga A.H., Postma D.S. Exhaled nitric oxide in 4-year-old children: relationship with asthma and atopy. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:455–461. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00079604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strunk R.C., Szefler S.J., Phillips B.R., Zeiger R.S., Chinchilli V.M., Larsen G. Relationship of exhaled nitric oxide to clinical and inflammatory markers of persistent asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:883–892. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steerenberg P.A., Janssen N.A., de Meer G., Fischer P.H., Nierkens S., van Loveren H. Relationship between exhaled NO, respiratory symptoms, lung function, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and blood eosinophilia in school children. Thorax. 2003;58:242–245. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.3.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uetani K., Der S.D., Zamanian-Daryoush M., de La Motte C., Lieberman B.Y., Williams B.R. Central role of double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase in microbial induction of nitric oxide synthase. J Immunol. 2000;165:988–996. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kao Y.J., Piedra P.A., Larsen G.L., Colasurdo G.N. Induction and regulation of nitric oxide synthase in airway epithelial cells by respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:532–539. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.9912068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane C., Knight D., Burgess S., Franklin P., Horak F., Legg J. Epithelial inducible nitric oxide synthase activity is the major determinant of nitric oxide concentration in exhaled breath. Thorax. 2004;59:757–760. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.014894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hansel T.T., Kharitonov S.A., Donnelly L.E., Erin E.M., Currie M.G., Moore W.M. A selective inhibitor of inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibits exhaled breath nitric oxide in healthy volunteers and asthmatics. FASEB J. 2003;17:1298–1300. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0633fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silkoff P.E., McClean P.A., Caramori M., Slutsky A.S., Zamel N. A significant proportion of exhaled nitric oxide arises in large airways in normal subjects. Respir Physiol. 1998;113:33–38. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(98)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zetterquist W., Pedroletti C., Lundberg J.O., Alving K. Salivary contribution to exhaled nitric oxide. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:327–333. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13b18.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marteus H., Mavropoulos A., Palm J.P., Ulfgren A.K., Bergstrom J., Alving K. Nitric oxide formation in the oropharyngeal tract: possible influence of cigarette smoking. Nitric Oxide. 2004;11:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vints A.M., Oostveen E., Eeckhaut G., Smolders M., De Backer W.A. Time-dependent effect of nitrate-rich meals on exhaled nitric oxide in healthy subjects. Chest. 2005;128:2465–2470. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Gouw H.W., Grunberg K., Schot R., Kroes A.C., Dick E.C., Sterk P.J. Relationship between exhaled nitric oxide and airway hyperresponsiveness following experimental rhinovirus infection in asthmatic subjects. Eur Respir J. 1998;11:126–132. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.11010126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy A.W., Platts-Mills T.A., Lobo M., Hayden F. Respiratory nitric oxide levels in experimental human influenza. Chest. 1998;114:452–456. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaul P., Singh I., Turner R.B. Effect of nitric oxide on rhinovirus replication and virus-induced interleukin-8 elaboration. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1193–1198. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9808043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Papadopoulos N.G., Bates P.J., Bardin P.G., Papi A., Leir S.H., Fraenkel D.J. Rhinoviruses infect the lower airways. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1875–1884. doi: 10.1086/315513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vareille M., Kieninger E., Edwards M.R., Regamey N. The airway epithelium: soldier in the fight against respiratory viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:210–229. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00014-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wark P.A., Johnston S.L., Bucchieri F., Powell R., Puddicombe S., Laza-Stanca V. Asthmatic bronchial epithelial cells have a deficient innate immune response to infection with rhinovirus. J Exp Med. 2005;201:937–947. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van de Kant K.D., Koers K., Rijkers G.T., Lima Passos V., Klaassen E.M., Mommers M. Can exhaled inflammatory markers predict a steroid response in wheezing preschool children? Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:1076–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bisgaard H., Hermansen M.N., Loland L., Halkjaer L.B., Buchvald F. Intermittent inhaled corticosteroids in infants with episodic wheezing. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1998–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guilbert T.W., Morgan W.J., Zeiger R.S., Mauger D.T., Boehmer S.J., Szefler S.J. Long-term inhaled corticosteroids in preschool children at high risk for asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1985–1997. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tepper R.S., Jones M., Davis S., Kisling J., Castile R. Rate constant for forced expiration decreases with lung growth during infancy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:835–838. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.9811025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xepapadaki P., Papadopoulos N.G., Bossios A., Manoussakis E., Manousakas T., Saxoni-Papageorgiou P. Duration of postviral airway hyperresponsiveness in children with asthma: effect of atopy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeMore J.P., Weisshaar E.H., Vrtis R.F., Swenson C.A., Evans M.D., Morin A. Similar colds in subjects with allergic asthma and nonatopic subjects after inoculation with rhinovirus-16. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.030. e1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lands L.C., Allen J., Cloutier M., Leigh M., McColley S., Murphy T. ATS Consensus Statement: Research opportunities and challenges in pediatric pulmonology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:776–780. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-661ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- Silkoff P.E., McClean P.A., Slutsky A.S., Furlott H.G., Hoffstein E., Wakita S. Marked flow-dependence of exhaled nitric oxide using a new technique to exclude nasal nitric oxide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:260–267. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg J.O., Farkas-Szallasi T., Weitzberg E., Rinder J., Lidholm J., Anggaard A. High nitric oxide production in human paranasal sinuses. Nat Med. 1995;1:370–373. doi: 10.1038/nm0495-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharitonov S.A., Chung K.F., Evans D., O'Connor B.J., Barnes P.J. Increased exhaled nitric oxide in asthma is mainly derived from the lower respiratory tract. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1773–1780. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alving K., Janson C., Nordvall L. Performance of a new hand-held device for exhaled nitric oxide measurement in adults and children. Respir Res. 2006;7:67. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vints A.M., Oostveen E., Eeckhaut G., Smolders M., De Backer W.A. Time-dependent effect of nitrate-rich meals on exhaled nitric oxide in healthy subjects. Chest. 2005;128:2465–2470. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurora P., Stocks J., Oliver C., Saunders C., Castle R., Chaziparasidis G. Quality control for spirometry in preschool children with and without lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:1152–1159. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200310-1453OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K., Zeger S. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]