Abstract

A universal vaccine against influenza remains a critical target, and efforts have recently focused on the stem of the hemagglutinin glycoprotein. In this issue of Cell and a related Cell Host & Microbe article, three studies identify broad protective epitopes in the hemagglutinin head domain that are exposed by trimer “breathing.”

A universal vaccine against influenza remains a critical target, and efforts have recently focused on the stem of the hemagglutinin glycoprotein. In this issue of Cell and a related Cell Host & Microbe article, three studies identify broad protective epitopes in the hemagglutinin head domain that are exposed by trimer “breathing.”

Main Text

The development of vaccines and the implementation of vaccination programs worldwide have led to the eradication of small pox and the elimination of poliomyelitis in most of the countries. However, many viruses, including influenza, have resisted efforts to develop a long-lasting protective vaccine. The underlying mechanism of this failure remains elusive, but it is believed that effective protective immunogens (epitopes) have not been identified.

More generally, the development of an effective vaccine against pathogens for which inactivated or attenuated vaccines failed remains an unsolved question in immunology. Both influenza and HIV (human immunodeficiency virus, the causative agent of AIDS) are the good examples of such issues. The influenza A virus HA (hemagglutinin) molecule consists of a “head” globular domain and a tail-“stem” domain and is believed to harbor both the immunogenic and protective components for vaccination. However, immunization with the head domain was proposed to elicit only subtype-specific, even strain-specific, protection; for example, the H5 head domain alone as immunogen elicits H5-specific protection (Xuan et al., 2011). To date, there are 18 defined subtypes (H1–H16 and HA-like H17/18) of influenza A virus HAs belonging to two broad groups (group 1 and group 2); thus, subtype-specific antibodies can only provide protection against a limited subset of viruses. On the other hand, the HA “stem” is the least variable region on the HA surface from the primary sequences. For this reason, great efforts have been focused on the development of influenza vaccines that depend on protective epitopes in the stem domain (Wu and Wilson, 2018), but the vaccination strategies used to elicit these antibodies, for example by removing the head domain, have not yet translated into a universal vaccine.

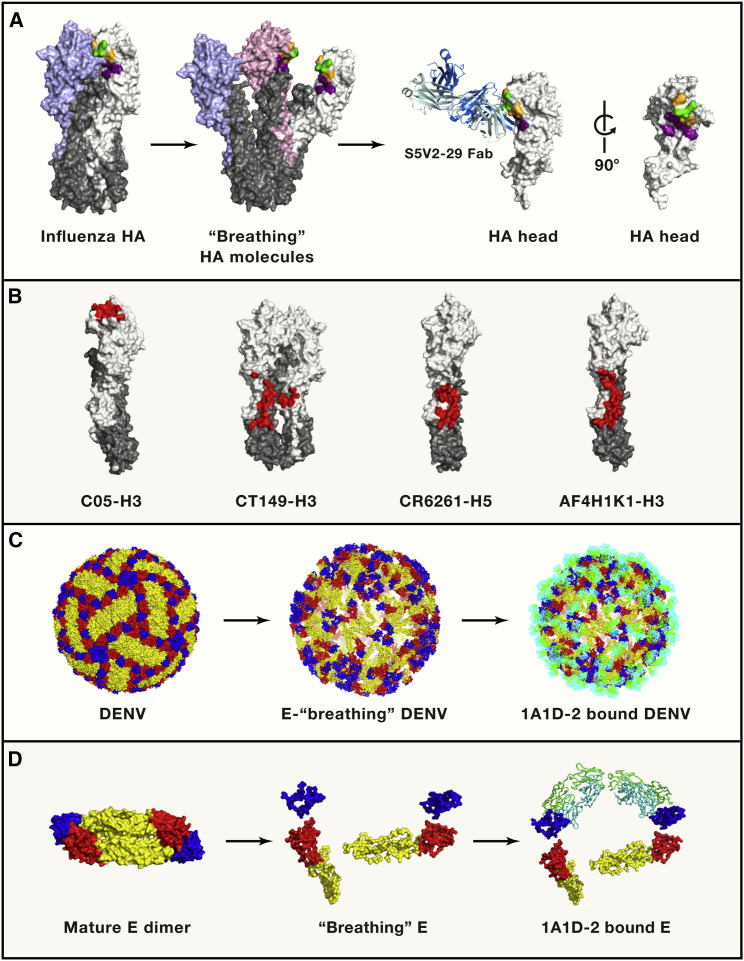

In this issue of Cell (Bangaru et al., 2019, Watanabe et al., 2019) and in an accompanying Cell Host & Microbe article (Bajic et al., 2019), three independent groups, for the first time, reported the identification of important epitopes hidden in the HA head domain and found them to be protective against broad-spectrum subtypes of influenza A viruses. They found that these novel protective epitopes are concealed at the contact surface between HA head domains in the trimeric HA (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

The Cryptic Epitopes Exposed by Virus “Breathing”

(A) The occluded epitope on influenza HA. Canonically, three HA molecules form a compact trimer as one unit on the virus surface (left). In the studies discussed here, the “breathing” of the HA trimer exposes a concealed epitope by breathing, which can be recognized by protective antibodies. The HA molecules are displayed in surface representation. The HA1 molecules are colored in white, pink, and pale blue, while the HA2 molecules are colored in gray. The epitope is presented by the representative structure of targeting HA-interfaced antibody-HA complex (H3-S5V2-29). The antibody heavy chain and light chain are colored in marine and pale blue, respectively. The conserved epitopes among the antibodies in the three papers are shown in green, the conserved epitopes among human antibodies are colored in orange, and the epitope of S5V2-29 is colored in deep purple.

(B) The epitopes of a representative RBS-targeted antibody (C05, PDB 4FQR), cross-binding of group 1 and group 2 HA stem antibody (CT-149, PDB: 4UBD), binding within group 1 HA stem (CR6261, PDB: 3GBM), and binding within group 2 HA stem (AF4H1K1, PDB: 5Y2L) are colored in red.

(C) The envelope glycoproteins (E proteins) on mature and immature DENV display different conformations. E dimers are observed on the mature DENV, while E trimers are presented on immature DENV particles. The exposed epitope can be recognized by breathing envelope glycoproteins on DENV. Several antibodies recognized the cryptic epitope on E proteins have been identified (1A1D-2, 4E11, 2H12, E111, and 3E31), and we take 1A1D-2 as an example to show the hidden epitope on the DENV particle. The E proteins are displayed by surface representation, with domains I, II, and III in red, yellow, and blue, respectively. The heavy chain and light chain of antibody 1A1D-2 are colored in green and cyan. The structure of mature particle and breathing DENV are based on PDB: 3J27 and 2R6P, respectively.

(D) The structures of E protein dimer on mature and breathing DENV particles and the 1A1D-2-E complex, with the same colors as in (C).

As noted above, previous studies have demonstrated that the conserved stem region is the promising target for broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) (Wu and Wilson, 2018), while rare bnAbs can recognize the “head” receptor binding site (RBS) with heterosubtypic activities. In the three studies reported here, the authors identify a novel class of anti-head antibodies isolated from vaccinated individuals or a mouse model of vaccination. One of these antibodies, FluA-20, was derived from a donor who had received many seasonal influenza vaccinations and experimental H5N1 and H7N9 subunit vaccines. In the second study, the representative S5V2-29 (one of 12 antibodies targeting the S5V2-C1 epitope) was obtained from human memory B cells of four donors who received the trivalent inactivated seasonal influenza vaccine (TIV) 2015–2016 Fluvirin. While isolated from distinct sources, all these antibodies recognize the occluded region on the HA head domain, which appears to be conserved among a divergent range of influenza HA subtypes. Accordingly, the human antibodies display a broad binding spectrum of HA molecules: FluA-20 can recognize the recombinant HA head domain from nearly all subtypes, except for H13, H16, and H7 of A/New York/107/2003 strain, while the collective breadth of five human antibodies (S5V2-29, H2214, S1V2-58, S8V2-17, and S8V2-37) targeting the S5V2-C1 epitope covers both group 1 and group 2 HAs (H1, H2, H3, H5, H7, H9, and H14).

In the third study, the authors present a murine model of vaccination that aims to elicit such antibodies by immunizing animals with glycans-modified HAs, for which the HA molecules are glycosylated to release some occluded epitopes. In this setting, mAb 8H10, one of the murine-derived VH5-9-1 antibodies that responded to glycan-modified H3 HongKong/1/1968 (HK-68), presents broad (but not complete) reactivity among historical H3s and a representative H4. The structural analysis of the three studies indicates that HA 220-loop is the key epitope recognized by these antibodies, with slightly different binding orientations (Figure 1). The 90-loop or the polypeptide chain between residue 91 and 106 also plays a role in this conserved epitope.

Interestingly, all of these anti-head antibodies lack neutralizing activity in vitro but could confer good protection in a murine model of infection. To explore the protection mechanism behind this phenomenon, Bangaru et al. examined the effects of mutations in the Fc portion of Flu-A20 and showed that its ADCC activity is dispensable for its protective effects in vivo. They further show that Flu-A20 can disrupt the HA0 trimer in vitro, a property that may underlie its protective role and ability to limit cell-to-cell spread. On the other hand, Watanabe et al. observed isotype-specific differences in protection (comparing IgG1 to IgG2c subtypes of the same S5V2-29 antibody) and attributed these effects to differences in both ADCC and CDC. Of note, this superior passive protection by IgG2c isoforms is consistent with previous stem-directed HA antibody studies (DiLillo et al., 2016).

Therefore, in addition to existing stem and RBS head epitopes, the discovery of non-RBS HA head epitopes by these three groups expands the potential immunogen components of broadly protective influenza vaccines.

The antibodies described here target a concealed head-interface epitope that might be conserved in part because of a relative lack of immune pressure. How do these antibodies gain access to the occluded epitopes? A recent experimental study suggests that HA exhibits a certain degree of reversible “breathing” conformational dynamics at both low and neutral pH (Das et al., 2018), providing the possible process for head separation required for interface exposure (Figure 1). Breathing and dynamics of the virus envelope proteins, and access of the protective antibodies, have been reported for other viruses, e.g., dengue virus (DENV) (1A1D-2 epitope exposure during breathing, see Figure 1), MERS-CoV, and HIV (Munro and Lee, 2018, Rey et al., 2018, Yuan et al., 2017). In the third study, Bajic et al. engineered the influenza HA molecules by introducing non-native potential N-linked glycosylation sites (PNGs) to redirect B cell responses. These glycans cover the immune-dominant (and variable) epitopes, which can elicit antibodies against a unique hidden epitope. Surprisingly, unlike glycan shield in HIV Env, hyperglycosylating HA creates an equivalent glycan shield without bias on the overall magnitude of the humoral responses.

Altogether, these three groups provide a comprehensive analysis of a new class of occluded epitopes on the influenza HA head domain. The antibodies to this epitope protect mice from infection, despite poor neutralizing activity in vitro, prompting us not to ignore the potential protective properties of non-neutralizing antibodies. Importantly, these studies support that the head-interface epitopes are conserved across most influenza groups and may not be under the immune pressure that would mediate the antigenic drift of the virus. Therefore, the occluded epitope might represent an ideal immunogenic candidate and should be considered in a universal influenza vaccine along with the HA-stem-based antigens. How we can obtain and immunize against more breathing epitopes remains a big issue for the future studies. Altogether, this work suggests a potential rethinking of our approach for the development of a universal vaccine against influenza by potentially going back to include both the head and stem domains and focusing on engineering work (e.g., glycosylation) that exposes such breathing epitopes.

Acknowledgments

Work in Prof. Gao’s laboratory is partly supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB29010202). Dr. Yan Wu is supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences Youth Innovation Promotion Association (2016086).

References

- Bajic G., Maron M.J., Adachi Y., Onodera T., McCarthy K.R., McGee C.E., Sempowski G.D., Takahashi Y., Kelsoe G., Kuraoka M. Influenza Antigen Engineering Focuses Immune Responses to a Subdominant but Broadly Protective Viral Epitope. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangaru S., Lang S., Schotsaert M., Vanderven H.A., Zhu X., Kose N., Bombardi R., Finn J.A., Kent S.J., Gilchuk P. A Site of Vulnerability on the Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin Head Domain Trimer Interface. Cell. 2019;177:1136–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.011. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das D.K., Govindan R., Nikić-Spiegel I., Krammer F., Lemke E.A., Munro J.B. Direct visualization of the conformational dynamics of single influenza hemagglutinin trimers. Cell. 2018;174:926–937.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D.J., Palese P., Wilson P.C., Ravetch J.V. Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza antibodies require Fc receptor engagement for in vivo protection. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:605–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI84428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro J.B., Lee K.K. Probing structural variation and dynamics in the HIV-1 Env fusion glycoprotein. Curr. HIV Res. 2018;16:5–12. doi: 10.2174/1570162X16666171222110025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey F.A., Stiasny K., Vaney M.C., Dellarole M., Heinz F.X. The bright and the dark side of human antibody responses to flaviviruses: lessons for vaccine design. EMBO Rep. 2018;19:206–224. doi: 10.15252/embr.201745302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe A., McCarthy K.R., Kuraoka M., Schmidt A.G., Adachi Y., Onodera T., Tonouchi K., Caradonna T.M., Bajic G., Song S. Antibodies to a Conserved Influenza Head Interface Epitope Protect by an IgG Subtype-Dependent Mechanism. Cell. 2019;177:1124–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.048. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N.C., Wilson I.A. Structural insights into the design of novel anti-influenza therapies. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018;25:115–121. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0025-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan C., Shi Y., Qi J., Zhang W., Xiao H., Gao G.F. Structural vaccinology: structure-based design of influenza A virus hemagglutinin subtype-specific subunit vaccines. Protein Cell. 2011;2:997–1005. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1134-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Cao D., Zhang Y., Ma J., Qi J., Wang Q., Lu G., Wu Y., Yan J., Shi Y. Cryo-EM structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15092. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]