Abstract

Prevention of renal failure: The Malaysian experience. Renal replacement therapy in Malaysia has shown exponential growth since 1990. The dialysis acceptance rate for 2003 was 80 per million population, prevalence 391 per million population. There are now more than 10,000 patients on dialysis. This growth is proportional to the growth in gross domestic product (GDP). Improvement in nephrology and urology services with widespread availability of ultrasonography and renal pathology has improved care of renal patients. Proper management of renal stone disease, lupus nephritis, and acute renal failure has decreased these as causes of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in younger age groups. Older patients are being accepted for dialysis, and 51% of new patients on dialysis were diabetic in 2003. The prevalence of diabetes is rising in the country (presently 7%); glycemic control of such patients is suboptimal. Thirty-three percent of adult Malaysians are hypertensive and blood pressure control is poor (6%). There is a national coordinating committee to oversee the control of diabetes and hypertension in the country. Primary care clinics have been provided with kits to detect microalbuminuria, and ACE inhibitors for the treatment of hypertension and diabetic nephropathy. Prevention of renal failure workshops targeted at primary care doctors have been launched, opportunistic screening at health clinics is being carried out, and public education targeting high-risk groups is ongoing. The challenge in Malaysia is to stem the rising tide of diabetic ESRD.

Keywords: end-stage renal disease, diabetic nephropathy, hypertension

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is a major problem in both developing and developed countries1 , 2. In developed economies, the rising incidence of ESRD among the elderly and diabetics is a major concern because it increases the cost of care in a treatment modality that already consumes a disproportionate share of the health care budget3., 4., 5.. Renal replacement therapy (RRT) uses 1% of the total health care budget in the United States, 2% of the health budget in the UK for treating 0.075% of the population, and 1.5% of the health care expenditure in France [accounting for 9.8% of the gross domestic product (GDP)], treating 0.034% of the population. In the developing world, the challenge facing health care providers is prioritizing finite health care resources in the face of many competing demands. Costly technology-dependent treatment programs such as RRT may not have the same priority as broad-based community health initiatives such as eradication of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and water-borne infectious diseases6. Recently, outbreaks of communicable diseases such as Severe Acute Respiratory syndrome7, which have a major impact on the economy, further strained health care resources and underlines the importance of good public health measures. This will be at the expense of tertiary care services.

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia with a population of 25 million. It is fortunate in being able to manage community and public health problems well, as indicated by such indices as maternal mortality rate (0.3 per 1000 live births) and infant mortality rate (6.3 per 1000 live births)8. It was able to allocate considerable resources to tertiary care services, including dialysis and renal transplantation.

RENAL REPLACEMENT THERAPY

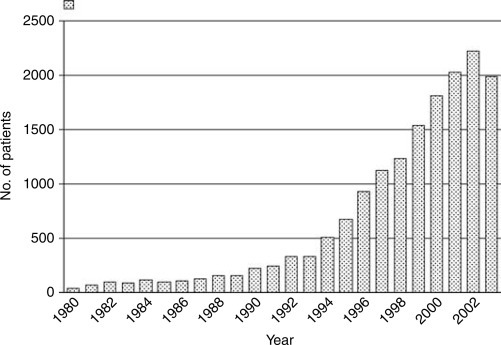

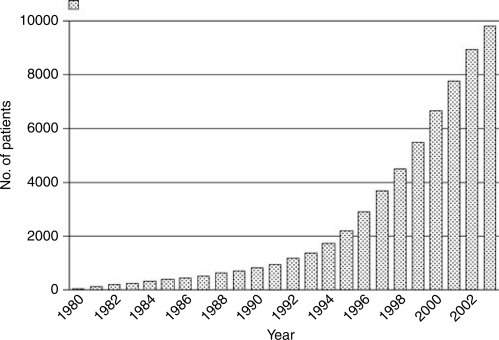

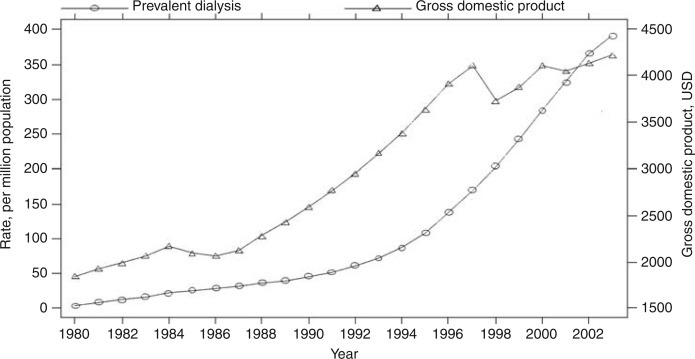

RRT in Malaysia has made considerable progress since its modest beginnings in the late 1970s. Dialysis, particularly hemodialysis treatment, showed an almost exponential growth. The new dialysis acceptance rate in the year 2003 was 80 per million population, while the prevalence rate on December 31, 2003, was 3919 patients per million per yearFigures 1 and2 . There are now more than 10,000 patients on dialysis in the country. The rapid growth corresponded with the economic development of the countryFigure 3 .

Figure 1.

New dialysis patients, Malaysia 1980 to 2003.

Figure 2.

Patients dialyzing in Malaysia on December 31, 1980 to 2003.

Figure 3.

Dialysis prevalence rate per million population and gross domestic product (USD), Malaysia 1980 to 2003.

The demographics of new dialysis patients have changed over the years, with increasing acceptance of older patients in recent cohorts. A major concern has been the trend where many of the new patients accepted for RRT were diabetics10. In the year 2003, diabetes mellitus was the cause of ESRD in 51% of all patients accepted for dialysis. The group classified as “unknown” has decreased from a high of 81% in 1980 to 30% presently. Although the exact diagnosis was not known, many in this group were suspected to have glomerulonephritis based on the clinical history and other findings.

Despite these achievements, there are still many patients with renal failure in the country who are not treated. The incidence of ESRD was estimated to be 86 per million population in 199111. It may be higher because there are no community-based studies on incidence of ESRD. The incidence in Singapore, an immediate neighbor, was higher, and was estimated to be 158 in 199712.

PREVENTION OF RENAL FAILURE INITIATIVES

In the past there has been no formal program in the health care system in Malaysia that specifically focuses on prevention of renal failure initiatives. Nonetheless, efforts at improving the level of nephrology and urology practices in the country over the last 20 years have led to improved level of care and better outcomes in many renal diseases. Such efforts include the training of nephrologists and urologists and allied health care staff. There were corresponding improvements in allied services such as imaging studies, particularly the widespread availability of ultrasonography, laboratory services, and renal pathology.

Renal stone disease, which at one time was not an infrequent cause of morbidity and renal failure, has become less of a problem partly due to the availability throughout the country of lithotripsy machines and other less invasive procedures to treat renal stones13. The management of glomerular diseases has improved considerably with the ready availability of renal biopsies and treatment regimens that include the use of cytotoxics, plasmapheresis, and dialysis for acute renal failure. This was reflected in recent registry reports where the number of patients with renal failure in the age group of 25 to 44 years has declined over the years10. The management of lupus nephritis with the judicious use of steroids and cytotoxics has led to better remission rates14., 15., 16.. One hundred and two systemic lupus erythmatosus (SLE) patients in Kuala Lumpur were studied in 1996; 5-year and 10-year patient survival was 86% and 70%, respectively. In 1984, Wang reported on 31 patients with membranous lupus nephropathy with a 6-year survival of 50% to 62%, depending on whether there was proliferation in the glomeruli or not. In a group of 85 patients with severe lupus nephritis (90% WHO class IV) reported in 2000 treated with intravenous cyclophosphamide, patient survival was 75% at 5 years, and 64% at 10 years.

It is diabetes mellitus, however, that is causing concern, and which has attracted the attention of health care providers and clinicians alike. Apart from renal failure, the other well-known organ complications associated with diabetes are similarly stretching health care resources in the country. The WHO has forecast that Asia will have the highest number of diabetic patients by 2030 compared to other regions in the world17. The world diabetic population is up from 171 million in 2000 to 194 million in 2003, and is estimated to reach 366 million by 2030.

Extrapolating from the second National Health and Morbidity survey (NHMS) of 20,208 adults older than 30 years of age, in 1996 the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the country was 7%, and the prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance was 5%18. The urban areas had a higher prevalence than rural areas. Earlier studies showed the prevalence to be increasing, and there was a trend to increase prevalence as the population moves from rural to urban areas17., 19., 20.. In 1984, the prevalence was 4% in a study in Kuala Selangor, Malaysia, and in 1986, the first NHMS reported the prevalence as 6.3%. With development, there is increasing urbanization and affluence, and the incidence of diabetes can be expected to increase further. There will be more diabetic end-stage renal failure in the future.

There was also a high prevalence of hypertension among the adult population in the country21. In the NHMS of 1996, 21,391 adults aged older than 30 years were surveyed. Approximately 33% of people older than 30 years old (about 2.6 million people in Malaysia) have hypertension. Of these, 23% have been prescribed medication and only 6% were controlled. In a study of 926 diabetic patients from different centers in peninsular Malaysia in 2000, mean HbA1c was 8.6%, and 61.1% of patients had HbA1c greater than 8%. The control of both hyperglycemia in diabetic patients and of the blood pressure in hypertensive patients is, therefore, far from satisfactory22., 23., 24..

It is this realization of the high prevalence of diabetes and hypertension and the poor glycemic and blood pressure control that the Ministry of Health, together with the professional societies such as the National Diabetes Institute, the Malaysian Society of Hypertension, and the Malaysian Society of Nephrology is embarking on a number of initiatives to control diabetes and hypertension and reduce the progression of renal failure. The initiatives also extend to nondiabetic renal diseases.

Among the initiatives is the setting up of a national-level coordinating committee to oversee the control of diabetes and hypertension in the country. The committee consists of representatives from the public sector, the universities, and professional societies. The committee formulated plans for screening of diabetes, diabetic nephropathy, and other organ complications. It endorses and disseminates clinical practice guidelines developed by professional groups. It monitors the general trend in diabetic care through a common data set developed for the public sector. The primary care physician, both in public and private sectors, has been identified as the key personnel for this program, and all efforts are channeled through the primary care clinics.

Diabetic nephropathy

In the public health care system, a common database was developed to monitor treatment of diabetic patients and track the development of complications, including nephropathy. Patients carry a treatment card, which incorporates the data set, and doctors and their staff fill in the appropriate entries at each encounter. An electronic version is being developed. All government primary care clinics are provided with kits to detect microalbuminuria. The guidelines call for this test to be done yearly in diabetic patients who are negative for overt albuminuria25 , 26. Diabetic patients have their renal function tested and blood pressure taken at regular intervals. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) are made available in the most rural clinic, and patients that are ACEI intolerant are prescribed angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) after a review by the internal medicine specialist. HbA1c test is now available in the smaller rural clinics. Most classes of antihypertensives are available in these clinics, as are the commonly used sulfonylureas, metformin, and insulin.

Continuing education activities

“Prevention of renal failure” workshops are now being held across the country (since 2003), targeting primary care doctors and allied health care staff. The focus is on the optimal management of diabetes and hypertension. The workshop also addresses screening for renal disease and the management of nondiabetic renal diseases. Five sessions have been done so far and two are in planning with the plan to have these sessions regularly in all Malaysian towns.

Public education activities

Ministry of Health Public Health Division, family medicine specialists, and Malaysian Diabetes Association have been holding public forums and screening workshops regularly for people with diabetes and family members.

Through the Ministry of Health's Healthy Lifestyle Campaign, which began in 1991, diabetes mellitus was the theme for the year 1996. The promotion of adopting a healthy lifestyle for the prevention of diabetes by creating awareness of a balanced diet, maintaining ideal body weight, and increasing physical activity was encouraged. The campaign emphasized raising awareness of the disease and its complications to the public. Guidelines on patient education were developed20.

CONCLUSION

The incidence and prevalence of renal diseases leading to ESRD is known in Malaysia, with the National Renal Registry reporting for its 11th year. Instead of continuing with increasing numbers of hemodialysis units and patients exponentially, a better way is to combat the disease at an earlier stage. Screening and detection of diabetic nephropathy is being done in primary care settings. Raising awareness of doctors and patients about the threat of renal failure is ongoing. Population-based screening has not been done on a coordinated scale. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the community is unknown. This may be incorporated as an objective of the third National Health and Morbidity survey that is due in 2006. The ultimate aim is to prevent illness, or else to prevent the complications of illness. When will society reap the benefits of prevention strategies and how it will be measured is still unknown. There are few data on the value of screening for early renal disease and how to focus this in order to ensure an optimum cost-benefit ratio.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Director General of Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia, for permission to publish this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barsoum R. End-stage renal disease in North Africa. Kidney Int. 2003;63(Suppl 83):S111–S114. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.23.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chugh K.S., Jha V. Differences in the care of ESRD patients worldwide: Required resources and future outlook. Kidney Int. 1995;50(Suppl):S7–S13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garella S. The costs of dialysis in the USA. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12(Suppl 1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mallick N. The costs of renal services in Britain. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12(Suppl 1):25–28. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobs C. The costs of dialysis treatments for patients with end-stage renal disease in France. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12(Suppl 1):29–32. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills A., Shillcutt S. 2004. Communicable diseases. Summary of Copenhagen Consensus Challenge Paper. http://www.copenhagenconsensus.com/. Accessed on June 5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lam W.K., Tsang K.W.T. The severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak—What lessons have been learned? J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2004;34:90–98. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry Of Health Malaysia . 2004. Information and Documentation System Unit, Planning and Development Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia. Health Facts 2001. http://www.moh.gov.my/Facts/2001.htm. Accessed on June 5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eleventh Report Of The Malaysian Dialysis And Transplant Registry 2003 . Eleventh Report of the Malaysian Dialysis and Transplant Registry 2003, Lim YN, Lim TO, Kuala Lumpur, http://www.crc.gov.my/nrr/report2003.htm. Accessed on June 4, 2004. 2004. All RRT in Malaysia; pp. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eleventh Report Of The Malaysian Dialysis And Transplant Registry 2003 . Eleventh Report of the Malaysian Dialysis and Transplant Registry 2003, Lim YN, Lim TO, Kuala Lumpur. http://www.crc.gov.my/nrr/report2003.htm. Accessed on June 4, 2004. 2004. Dialysis in Malaysia; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooi L.S. A registry of patients with end stage renal disease—The experience at Hospital Sultanah Aminah, Johor Bahru. Med J Malaysia. 1993;48:185–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramirez S., Hsu S., Mcclellan W. Taking a public health approach to the prevention of end-stage renal disease: The NKF Singapore Program. Kidney Int. 2003;63(Suppl 83):S61–S65. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.13.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sreenevasan G. Urinary stones in Malaysia—Its incidence and management. Med J Malaysia. 1990;45:92–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang F., Looi L.M. Systemic lupus erythematosus with membranous lupus nephropathy in Malaysian patients. Q J Med. 1984;53:209–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paton N.I.J., Cheong I., Kong N.C.T., Segasothy M. Mortality in Malaysians with systemic lupus erythematosus. Med J Malaysia. 1996;51:437–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan A.Y.K., Hooi L.S. Outcome of 85 lupus nephritis patients treated with intravenous cyclophosphamide: A single centre 10 year experience. Med J Malaysia. 2000;55:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wild S., Roglic G., Green A. Global prevalence of diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim T.O., Ding L.M., Zaki M. Distribution of blood glucose in a national sample of Malaysian adults. Med J Malaysia. 2000;55:65–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khebir B.V., Osman A., Khalid B.A. Changing prevalence of diabetes mellitus amongst rural Malays in Kuala Selangor over a 10-year period. Med J Malaysia. 1996;51:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rugayah B. 2004. Second National Health and Morbidity Survey: Diabetes mellitus among adults aged 30 years and above. http://www.diabetes.org.my/DiabMalaysia.htm. Accessed on June 5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim T.O., Ding L.M., Goh B.L. Distribution of blood pressure in a national sample of Malaysian adults. Med J Malaysia. 2000;55:90–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mustaffa E. Diabetes in Malaysia: Problems and challenges. Med J Malaysia. 1990;45:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ismail I.S., Nazaimoon W.M., Mohamad W.B. Sociodemographic determinants of glycaemic control in young diabetic patients in peninsular Malaysia. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;47:57–69. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(99)00104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim T.O., Zaki M. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in the Malaysian adult population: Results from the National Health and Morbidity Survey 1996. Singapore Med J. 2004;45:20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malaysian Diabetes Association . 2004. Non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: Malaysian Consensus, 2nd ed., 1996. http://www.acadmed.org.my/html/index.shtml. Accessed on June 4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Academy Of Medicine Malaysia, Ministry Of Health Malaysia . 2004. Clinical practice guidelines on diabetic nephropathy, 2003. http://www.acadmed.org.my/html/index.shtml. Accessed on June 4. [Google Scholar]