Summary

Human disease associated with influenza A subtype H5N1 reemerged in January, 2003, for the first time since an outbreak in Hong Kong in 1997. Patients with H5N1 disease had unusually high serum concentrations of chemokines (eg, interferon induced protein-10 [IP-10] and monokine induced by interferon γ [MIG]). Taken together with a previous report that H5N1 influenza viruses induce large amounts of proinflam-matory cytokines from macrophage cultures in vitro, our findings suggest that cytokine dysfunction contributes to the pathogenesis of H5N1 disease. Development of vaccines against influenza A (H5N1) virus should be made a priority.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus subtype H5N1 caused disease in 18 patients with six deaths in Hong Kong in 1997. This outbreak was the first documented instance of a purely avian influenza virus causing severe respiratory illness in human beings.1, 2 Here, we report the re-emergence of human H5N1 disease and discuss the possible pathogenesis of the disease.

A family of five from Hong Kong, People's Republic of China, visited Fujian province, mainland China, from Jan 26, to Feb 9, 2003. The 7-year-old daughter developed high fever and respiratory symptoms 2 days after arriving there and died of a pneumonia-like illness 7 days after the onset of symptoms. The exact cause of death could not be ascertained since the girl was buried in mainland China. The family returned to Hong Kong on Feb 9, 2003. The father, a 33-year-old with previous good health, was admitted on Feb 11, 2003, with a 4-day history of fever, malaise, sore throat, cough with blood-stained sputum, and bone pain. He had a lymphocyte count of 0·6×109/L (normal range 1·5–4·0×109/L) and radiological evidence of right lower-lobe consolidation. Bacteriological investigations including sputum and blood cultures and acid-fast stain of sputum were unremarkable. Despite treatment with intravenous cefotaxime and oral clarithromycin, clinical and radiological signs showed that the patient was deteriorating. 2 days after admission, oral oseltamivir (75 mg twice daily) was added to his treatment regimen. The patient was electively intubated because of progressive respiratory distress, but his condition worsened and he died 6 days after admission.

Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 was detected by cell-culture methods and by RT-PCR in the nasopharyngeal aspirate collected at day 6 of illness. Serological investigations and cultures to detect other respiratory bacterial and viral pathogens (including RT-PCR for severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS] coronavirus) were negative.

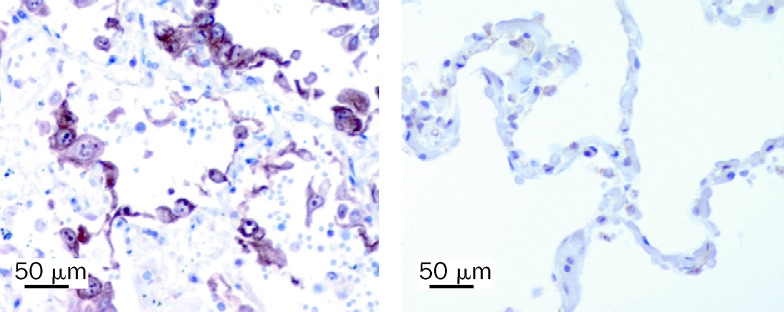

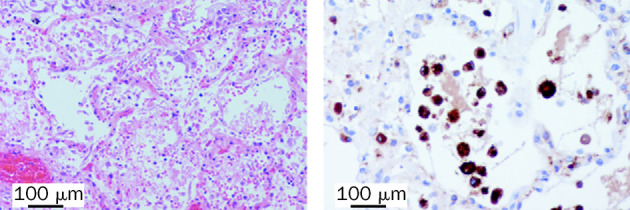

Autopsy showed features of oedema, haemorrhage, and fibrin exudation in the lung (figure 1 ). CD68+ macrophages were prominent within alveoli (figure 1) and there were increased numbers of CD3+ T cells in the interstitium. Type-2 pneumocyte hyperplasia was focally present and these pneumocytes showed increased expression of TNF compared with that in the lung of a patient who died of a non-infective cause (figure 2 ). We did not detect any viral antigen in cells expressing TNF. We did note parafollicular reactive histiocytes with haemophagocytosis in the bronchial and hilar lymph nodes. Bone marrow was hypercellular and we identified reactive haemophagocytosis. We did not find evidence of any clinically significant changes in other organs.

Figure 1.

Histological stains of lung tissue from 33-year-old man with H5N1 pneumonia

Left panel: intra-alveolar oedema, haemorrhage, and increased fibrin and alveolar macrophages are evident. Haematoxylin and eosin stain used. Right panel: macrophages were shown by use of immunohistochemical staining with antibody to CD68.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical staining for TNF in lung tissue from patient with H5N1 pneumonia and a patient who died from non-infective illness

Stains made with monoclonal antibody SC-7317 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1/10 with antigen retrieval. The 33-year-old man with H5N1 pneumonia (left panel) shows greater staining of alveolar epithelial cells than does the control (right panel)

With the use of culture and RT-PCR, we detected influenza A in the right and left lung and we noted focal extracellular staining for influenza A antigen (Imagen, DAKO, Cambridge, UK) in cells of the alveolar exudate. Influenza virus was not detectable by RT-PCR or immunofluorescence in other organs.

On Feb 12, 2003, the family's previously healthy 8-year-old son was admitted with a 3-day history of an influenza-like illness. There was radiological evidence of left lingular lobe consolidation. The boy reported that he had had close contact with live chickens during his visit to Fujian. He was treated with intravenous cefotaxime, oral clarithromycin, and oral amantadine for 1 week. His lymphocyte count dropped to a nadir of 0·7×109/L (normal range for children 1·5–7·0×109/L) 5 days after disease onset. Liver transaminase (ALT) concentrations reached a maximum of 375 IU/L (normal range 1–40 IU/L) 8 days after onset. Influenza A virus (H5N1) was cultured from his nasopharyngeal aspirate collected on day 5 of illness. Microbiological investigations for bacterial and viral pathogens, including SARS coronavirus, were negative. The boy made an uneventful clinical recovery. The role of amantadine therapy in his clinical recovery is uncertain since the virus has an aminoacid substitution (Ser to Asn) at position 31 of the M2 gene that is invariably associated with amantadine resistance (unpublished data).

The clinical and pathological features of these two patients with H5N1 disease were similar to those reported previously.1, 3 In addition to the progressive primary viral pneumonia, there was lymphopenia and a raised transaminase. Furthermore, as in previous patients, there was evidence of activated histiocytes and reactive haemophagocytosis in the lymph nodes and bone marrow.3

RT-PCR for influenza was only positive in one of two nasopharyngeal specimens gathered from each patient between day 5–10 of illness and quantitative RT-PCR assay showed fewer than 1·5 log10 copies of influenza M gene per μL. By comparison, viral load in five patients with influenza A (H3N2) infection at day 3–9 of illness had a mean viral load of 3·5 log10 copies per μL (range 2·5–4·8 log10 [SD 1 log10]). During the outbreak of human H5N1 disease in 1997, investigators reported that the number of cells positive by direct immunofluorescence for influenza A antigen in nasopharyngeal aspirate from patients with H5N1 disease was lower than in those with H3N2 disease (unpublished data). Rapid diagnostic methods for influenza such as direct immunofluorescence are less sensitive for diagnosis of H5N1 influenza, probably because of lower viral load in nasopharyngeal aspirate.1

We did partial genetic sequencing across the HA1–HA2 cleavage site of haemagglutinin of the H5N1 virus isolates from the 33-year-old man and the 8-year-old boy. Our results confirmed that the virus had the multibasic aminoacid motif associated with HPAI viruses and that the haemagglutinin had high homology to the H5 haemagglutinin of the H5N1 virus isolated in 1997.2

We measured serum cytokine and chemokine concentrations (Cytometric Bead Assay from BD Biosciences, San Diego CA, USA) in our two patients. Cytokine concentrations in early (day 1–3 of illness) and late (day 9–10) serum samples from six other adults with influenza—three with influenza A and three with influenza B—and five serum samples from healthy adults were used for comparison (table ). Serum concentrations of interferon induced protein-10 (IP-10) and monokine induced by interferon γ (MIG) in patients with uncomplicated human influenza A or B were high early in the illness, but fell to within normal range by day 9–10 after disease onset. By contrast, serum IP-10 and MIG concentrations in our 33-year-old patient were higher (ie, a difference greater than 2 SD from the mean) than in patients with uncomplicated influenza A or B disease and these concentrations continued to increase. On the third day of illness, the 8-year-old patient also had higher serum concentrations of IP-10 and MIG than did patients with uncomplicated influenza; but these high concentrations dropped by day 5 of illness. Of note is that the control patients with influenza were all adults and we had no age-comparable controls for the 8-year-old boy.

Table.

Serum cytokine concentrations of patients with influenza subtype H5N1, patients with influenza A and B infection, and healthy controls

|

Serum cytokine concentrations (ng/L) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP-10 | MCP-1 | MIG | RANTES | Interleukin 8 | ||

| Patient 1*with influenza A (H5N1) | ||||||

| 6 days after illness onset | 36000 | 644 | 5100 | 24000 | 30 | |

| 8 days after illness onset |

>50000 |

2316 |

17000 |

23000 |

90 |

|

| Patient 2†influenza A (H5N1) | ||||||

| 3 days after illness onset | 16000 | 85 | 1400 | 29000 | 41 | |

| 5 days after illness onset |

1300 |

80 |

343 |

>50000 |

22 |

|

| Influenza A or B controls‡ | ||||||

| 1–3 days after symptoms | ||||||

| Median | 2650 | 330 | 600 | NA§ | 9 | |

| Mean | 3582 | 520 | 675 | NA§ | 11 | |

| SD | 3952 | 599 | 426 | NA§ | 8 | |

| Range | 490–11000 | 100–1700 | 330–1500 | 20000–>50000 | 3–24 | |

| 9–10 days after symptoms | ||||||

| Median | 335 | 125 | 250 | NA§ | 9 | |

| Mean | 332 | 131 | 260 | NA§ | 37 | |

| SD | 104 | 47 | 86 | NA§ | 70 | |

| Range |

190–450 |

75–200 |

170–410 |

14000–>50000 |

6–180 |

|

| Healthy controls¶ | ||||||

| Median | 159 | 76 | 198 | 17884 | 11 | |

| Mean | 202 | 107 | 238 | 18143 | 19 | |

| SD | 83 | 63 | 104 | 712 | 16 | |

| Range |

129–301 |

43–181 |

129–363 |

17285–19156 |

8-44 |

|

33-year-old man.

8-year-old boy.

n=6; age-range 23–41 years.

Mean, median and SD cannot be calculated since some results are beyond the upper range of assay.

n=5; age-range 21–37 years.

Concentrations of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), RANTES, and interleukin 8 in patients with H5N1 disease did not differ much from other patients with influenza (table). TNF α, interleukin 1 β, interleukin 10, and interleukin 12 were undetectable in serum samples from patients with H5N1 infection while low concentrations of interleukin 6 were detected in the serum of the 33-year-old man on day 8 of his illness (data not shown).

Since the controls with influenza had uncomplicated disease, we are unable to say whether the high concentrations of serum IP-10 and MIG were a consequence of the pneumonia in patients with H5N1 infection or whether they were the result of a hypercytokinaemia with a role in pathogenesis. However, we have shown previously that H5N1 virus isolated from humans in 1997 are able to induce the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines including TNF α, type 1 interferons4 and IP-10 (unpublished data) from macrophages infected in vitro; we have postulated that immune dysregulation has a part in pathogenesis of this disease.4 TNF α and interferons are early-phase cytokines that act locally to trigger a cascade of other cytokines including IP-10, interleukin 1, and interleukin 6. IP-10 is a macrophage chemoattractant and its presence might explain the prominent macrophage inflammatory infiltrate in the lung (figure 1). Secretion of MIG is induced by interferon γ released from activated T helper cells as well as TNF α and it indicates the activation of the Th-1 pathway. Taken together with the in-vitro data that H5N1 viruses greatly stimulate cytokine release, the unusually high concentrations of IP-10 and MIG in serum could be the result of a massive overall induction of cytokines such as TNF α within the microenvironment of the lung, thus contributing to disease pathogenesis.

Although TNF α was undetectable in serum, we did note evidence of its expression in epithelial cells of the alveoli (figure 2). Deaths associated with primary human influenza (H3N2 or H1N1) pneumonia are uncommon and, thus, currently we do not know whether these patients show ennhanced TNF α expression within pneumocytes.

In March, 2003, there was an outbreak of avian influenza A virus subtype H7N7 in the Netherlands, and one person died as a result of infection.5 More recently, H5N1 has been associated with human disease and death in Vietnam and Thailand.6 Although avian influenza viruses are not usually transmissible to human beings, some clearly do pose a substantial threat to human health. Therefore, workers planning for influenza pandemics must understand the mechanisms of interspecies transmission and the basis for the unusual pathogenicity of such disease in human beings. Furthermore, the re-emergence of H5N1 disease in humans emphasises the need to develop a vaccine against this virus.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The study was sponsored by Public Health Service research grant AI95357 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the Wellcome Trust (grant GR067072/D/02/Z). The sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Contributors

J S M Peiris planned the study and wrote the manuscript. W C Yu, S T Lai, C W Leung, and T K Ng investigated the patients and compiled the clinical data; C Y Cheung carried out the cytokine assays; W F Ng and J M Nicholls were responsible for the autopsy and immunohistochemical studies, and Y Guan, W L Lim and K H Chan did the virological studies. K Y Yuen and J M Nicholls contributed to study design, critical analysis of the data, and writing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Yuen KY, Chan PKS, Peiris M. Clinical features and rapid viral diagnosis of human disease associated with avian influenza A H5N1 virus. Lancet. 1998;351:467–471. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)01182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claas ECL, Osterhaus ADME, van Beek R. Human influenza A H5N1 virus related to a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Lancet. 1998;351:472–477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.To KF, Chan PKS, Chan KF. Pathology of fatal human infection associated with avian influenza A H5N1 virus. J Med Virol. 2001;63:242–246. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200103)63:3<242::aid-jmv1007>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung CY, Poon LLM, Lau ASY. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in human macrophages by influenza A (H5N1) viruses: a mechanism for the unusual severity of human disease. Lancet. 2002;360:1831–1837. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koopmans M, Wilbrink B, Conyn M. Transmission of H7N7 avian influenza A virus to human beings during a large outbreak in commercial poultry farms in the Netherlands. Lancet. 2004;363:587–593. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15589-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO Confirmed human cases of avian influenza A (H5N1) http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/en/ (accessed Feb 12, 2004).