Abstract

Rapid methods for the detection and clinical treatment of human norovirus (HuNoV) are needed to control foodborne disease outbreaks, but reliable techniques that are fast and sensitive enough to detect small amounts of HuNoV in food and aquatic environments are not yet available. We explore the interactions between HuNoV and concanavalin A (Con A), which could facilitate the development of a sensitive detection tool for HuNoV. Biophysical studies including hydrogen/deuterium exchange (HDX) mass spectrometry and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) revealed that when the metal coordinated region of Con A, which spans Asp16 to His24, is converted to nine alanine residues (mCon AMCR), the affinity for HuNoV (GII.4) diminishes, demonstrating that this Ca2+ and Mn2+ coordinated region is responsible for the observed virus-protein interaction. The mutated carbohydrate binding region of Con A (mCon ACBR) does not affect binding affinity significantly, indicating that MCR of Con A is a major region of interaction to HuNoV (GII.4). The results further contribute to the development of a HuNoV concentration tool, Con A-immobilized polyacrylate beads (Con A-PAB), for rapid detection of genotypes from genogroups I and II (GI and GII). This method offers many advantages over currently available methods, including a short concentration time. HuNov (GI and GII) can be detected in just 15 min with 90% recovery through Con A-PAB application. In addition, this method can be used over a wide range of pH values (pH 3.0 – 10.0). Overall, this rapid and sensitive detection of HuNoV (GI and GII) will aid in the prevention of virus transmission pathways, and the method developed here may have applicability for other foodborne viral infections.

Keywords: Human norovirus (GI and GII), Concanavalin A, Polyacrylamide bead, Metal coordination, Lectin

1. Introduction

Noroviruses (NoV) are non-enveloped single-stranded positive-sense RNA viruses belonging to the Caliciviridae family, and are divided into seven genogroups (GI – GVII) based on viral capsid gene sequences [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. The genotypes in genogroups GI, GII, and GIV, referred to collectively as human norovirus (HuNoV), are a major cause of acute water- and food-borne outbreaks of viral gastroenteritis worldwide [1], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. HuNoV is responsible for more than 90% of viral gastroenteritis and more than 50% of all gastroenteritis outbreaks; this virus causes acute diarrhea and vomiting, which typically resolve within 2 or 3 days, but can result in life-threatening dehydration in children and the elderly [7], [11].

For the detection and concentration of HuNoV, extensive studies have been performed to culture NoV in immune T and human B cell lines; however, these systems are not a robust model due to the low-level of viral replication and high-level of virus shedding [12], [13]. Hence, electron microscopy, immunological tests, electrochemical sensing, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based molecular assays have been adopted to detect NoV [14]. Despite the fact that electrochemical biosensing, using NoV-specific aptamers, is rapid, sensitive and accurate, reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) are the gold standards for NoV detection due to their wide applicability. However, sample preparation for these methods to detect viral contamination in food and water is complicated by factors such as large sample volumes, low viral titers, and compounds that interfere with nucleic acid amplification [15]. Methods available for NoV concentration, such as swab sampling, polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation, ultracentrifugation, cationic separation, immune concentration, and organic flocculation, have limitations due to their narrow pH ranges, time requirements, and difficulties in handling multiple samples at a time [16], [17]. Therefore, an alternative method is necessary to overcome the limitations of such methods.

Several lectins used as carbohydrate-binding agents have been shown to effectively inhibit HIV and emerging viruses, such as Ebola virus and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS), by interacting with the glycoproteins in enveloped viruses [18], [19], [20]. Concanavalin A (Con A), a lectin from jack bean, binds specifically to the non-reducing mannosyl and glycosyl residues of polysaccharides, glycoproteins, and glycolipids. Preliminary reports have demonstrated that Con A can bind to a broad range of enveloped viruses, including varicella-zoster, infectious bronchitis, and dengue viruses by interacting with the glycoproteins present on the viral surface [21], [22].

In this study, the interaction details between Con A and HuNoV (GII.4) were characterized based on a comparison of the deuterium exchange ratio for protein structural modification using hydrogen/deuterium exchange equipped with a mass spectrophotometer (HDX-MS). The interaction between HuNoV (GII.4) and Con A was also characterized by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and biolayer interferometry (BLI) through mutational studies. Furthermore, a rapid technique for use with PCR assay using specific primers for the detection of HuNoV was developed to concentrate specific HuNoV via Con A immobilization on polyacrylate beads (Con A-PAB). This application was evaluated by measuring the recovery of different genotypes of GI and GII HuNoV from different food matrices at broad pH ranges. Overall, this rapid and sensitive detection of HuNoV will aid in the prevention of virus transmission pathways, and the method developed here may have applicability for other foodborne viral infections, especially HuNoV (GI and GII).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Virus and materials

Seven genotypes of HuNoV-positive stool samples (Gwangju Health and Environment Research Institute, Gwangju, South Korea) were diluted to a 10% suspension in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4. The titer of HuNoV, determined by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), was 106 copies/mL. All virus suspensions were aliquoted in 1 mL EP tubes and stored at - 80 °C until use. Con A isolated from Canavalia ensiformis (Jack bean, C7275, Sigma, St. Louis, USA) was purchased. A mouse monoclonal antibody specific to the norovirus capsid protein (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used for Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) analysis.

2.2. Generation of standard curves

To construct HuNoV standards for qRT-PCR, the target gene was cloned into the pGEM T-Easy vector (Promega, USA) and then was transformed into the DH5α competent cells (Enzynomics, Korea). The plasmids were purified using the AccuPower plasmid mini kit (Bioneer, Korea) and converted to copy numbers based on measurements of DNA concentration using the NanoDrop 2000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) [23]. A ten-fold serial dilution was prepared in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-water ranging from 101 to 108 copies/μL. A 2.0 μL template from each dilution was used to prepare a standard curve for qRT-PCR [24].

2.3. Protein expression and purification

P-domain of HuNoV GII.4 VA387, mCon AMCR, and mCon ACBR were expressed from a pGEX4T-1 plasmid in Escherichia coli Rosetta 2 (DE3) pLysS cells (Novagen) [25]. Cultures were grown in LB broth containing ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and chloramphenicol (34 μg/mL) at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.5. Con A was induced with 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, and 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 16 °C overnight. GII.4 VA387 was induced with 0.2 mM IPTG at 16 °C overnight. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 20 min, and the pellet was re-suspended in 20 mL lysis solution (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 1 mg/mL lysozyme) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche, Switzerland). Samples were lysed by three passes through a French press disruptor (Stansted SPCH). The cleared lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 20 min, and glutathione S-transferase (GST) purification was performed on a 2 mL bed volume of glutathione agarose affinity resin (Pierce) pre-equilibrated with Tris-buffered saline (TBS, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 150 mM NaCl). The lysate was then incubated with glutathione-agarose resins at 4 °C for 2 h on a rotator. To remove non-specific binding proteins, the resins were pelleted by centrifugation at 700 × g for 3 min and washed five times with 10 resin-bed volumes of TBS. GST-tagged proteins were then eluted with TBS containing 10 mM GSH (3 mL). The purified proteins were appropriately concentrated using 30 kDa molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) centrifugal filter units (Amicon Ultra-15, Merck Millipore). The GST-tagged proteins were then treated with thrombin to liberate the fusion proteins, which were subsequently purified with a GSTrap FF (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) and HiTrap Benzamidine FF columns (GE Healthcare), and stored at −80 °C until use.

2.4. Hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS)

The Con A proteins from C. gladiate and C. ensiformis were diluted to 5 pmoles in 20 μL of a buffer composed of 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) and 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.4) [26]. The protein mixture was diluted to 5 pmoles of Con A and 1,100 pmoles of VA387 protein of HuNoV in 20 μL of a buffer composed of 10 mM HEPES and 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.4). Hydrogen/deuterium exchange (HDX) was initiated by mixing 9.0 μL of diluted protein with 27.0 μL of the D2O buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% DDM (n-Dodecyl β-D-maltoside)). The mixtures were then incubated at various time intervals including 5 s, 10 s, 30 s and 100 s, and then quenched by adding 72.0 μL of quench buffer (100 mM K2HPO4, pH 2.4, 2.0 M Guanidine hydrochloride) in a 1 °C tray at the indicated time points [27].

The quenched samples were digested online by passing through an immobilized pepsin column (2.1 × 30 mm, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) at a flow rate of 100 μL/min with 0.1% formic acid in H2O at 20 °C. Pepsin digested peptides were subsequently collected on a C18 VanGuard trap column (1.7 μm × 30 mm, Waters) for 3 min desalting with 0.1% formic acid in H2O, and then separated by ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) using ACQUITY UPLC C18 column (1.7 μm, 1.0 × 100 mm, Waters, Milford, MA) at a flow rate of 40 μL/min with an acetonitrile gradient by using two pumps, which started with 10% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid and increased to 85% acetonitrile over the next 12 min. The mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid in H2O. To minimize the back-exchange of deuterium to hydrogen, the sample, solvents, trap and UPLC column were all maintained at pH 2.5 and 0 °C during analysis. Mass spectral analysis was performed with a Synapt G2-Si equipped with a standard ESI source (Waters, Milford, MA). The mass spectra were acquired in the range of m/z 100–2000 for 16 min in the positive ion mode.

2.5. Peptide identification and HDX data processing

Peptic peptides were identified in non-deuterated samples with ProteinLynx Global Server 3.0 (Waters, Milford, MA). Peptide search parameters were strictly applied, those being a maximum of 1 missed cleavage for non-specific enzymes, a 10 ppm MS/MS ion search, and a peptide ion tolerance of 1 ppm. To process HDX data, the deuterium exchange ratio in each peptide was determined by measuring the centroid of the isotopic distribution using HDExaminer 2.0 (Sierra Analytics Inc., Modesto, CA).

2.6. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

Protein structural changes of Con A, VA387, and complex of Con A with VA387 in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) were monitored using a JASCO J-710 Spectropolarimeter (Jasco Corp., Tokyo, Japan), which was used with a 0.1 cm path length cuvette from 200 to 260 nm at a scan speed of 50 nm/min. Control spectra obtained with titrations of vesicle suspensions in buffer alone were subtracted from the experimental spectra. An average of four accumulations was collected for each sample, and data was plotted using Kaleidagraph 4.1.3 (Synergy Software, Reading, PA).

2.7. Modification of sensor chip surface

The Au chip was cleaned with Piranha etch solution [10 mL of H2SO4 (97.5%, v/v): 5 mL of H2O2 (30%, v/v)] for 2 min followed by extensive washing with ultra-pure water (UPW) [28]. As a preliminary cleaning step, an Au sensor chip covered with a 50-nm-thick layer of unmodified gold was cleaned in ethanol for 2 min. The sensing surface of the Au sensor chip was immersed in diethylene glycol alkanethiol [HS-(CH2)11-EG2-OH] and carboxyl-terminated diethylene glycol alkanethiol[HS-(CH2)11-EG2-OCH2COOH] for 24 h to form self-assembled monolayers on the sensor surface [28]. After cleaning with ethanol, a solution consisting of 0.2 M 1-Ethyl-3-(3'dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC) and 0.1 M N-hydroxy succinimide (NHS) in ethanol was added onto the sensor surface and incubated for 1 h to activate the terminal carboxyl group. Subsequently, the sensor surface was washed with ethanol, and was incubated for 1 h in 2 mL of HuNoV (104 copies/mL) in PBS. HuNoV solution was rinsed with 5 mL of PBS buffer and distilled water. As a negative control chip, HuNoV-free solution was incubated with 1.0 M ethanolamine (pH 8.5) for 1 h by quenching the NHS-activated sites.

2.8. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis

The Biacore 2000 instrument (BIAcore AB, Uppsala, Sweden) was set to a constant temperature of 25 °C. On the day of the sample measurement, the sensor chip was activated twice with degassed physiological running buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; and 1 mM CaCl2) and equilibrated at a flow rate of 50 μL/min until a stable baseline was achieved. Before the sample measurement, at least three injection and regeneration cycles were performed by injecting 10 μL of 30 mM NaOH at a flow rate of 20 μL/min. Stabilization time of the baseline after each regeneration cycle was set to 1 min at 20 μL/min. A concentration series (250; 125; 62.5; 31.3; 15.6; 0 nM) of C. ensiformis Con A, C. gladiate Con A, mutated metal coordinated region of Con A (mCon AMCR), or mutated carbohydrate binding region (mCon ACBR) were prepared in physiological running buffer and injected starting with the lowest concentration. Regeneration was performed after each measurement. All analysis was performed at 25 °C using the KINJECT command defining an association time of 180 s and a dissociation time of 180 s at a flow rate of 20 μL/min. BIAevaluation 3.1.1 software (BIAcore AB) was used for data analysis and for the calculation of dissociation constants (KD) by fitting the data to a 1:1 binding with a drifting baseline algorithm.

2.9. Biolayer interferometry (BLI) analysis

The binding of HuNoV to Con A was measured with bio-layer interferometry-based BLItz system (ForteBio Inc., CA) as previously described. Amine reactive second generation (AR2G) biosensors were hydrated in distilled water for 10 min, and activated in 10 mM sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide (s-NHS) and 20 mM EDC. The HuNoV (GII.4) was immobilized on biosensors at concentrations of 106 copies, and then 2 μM of Con A (C. ensiformis), BSA (bovine serum albumin, Sigma-Aldrich), SBA (soybean agglutin, Sigma-Aldrich), and Con AMCR were measured at 25 °C, respectively. To measure the interaction between Con A and HuNoV (GII.4), the association and dissociation times were 180 and 240 s, respectively. Sensorgrams were measured on a BLItz system and referenced against the buffer reference signal using the Data Analysis software 7.1.0.36 (ForteBio Inc., CA).

2.10. Preparation of the Con A immobilized polyacrylate beads (Con A-PAB)

Carboxylic acid functionalization of the polyacrylate bead (WK-60L, Samyang Co., Korea) was determined using the concentration of carboxylic acid groups (43 μmoL/g) as determined by methylene blue sorption measurement [29]. Polyacrylate beads (0.4–1.2 mm diameter) were used as the filler and support for Con A immobilization and 1 g of these beads were added to 2 mL of a solution of pentafluorophenol (79 mg, 430 μmol) and EDC (41 mg, 215 μmol) to activate the beads. The beads were then gently rotated on a Dynal sample mixer at low speed (approximately 20–30 rpm) for 2 h at room temperature. After activation of carboxylic acid groups, the beads were washed with absolute ethanol three times and Con A (3.0 mg) was dissolved in sodium bicarbonate buffer (0.2 M NaHCO3, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.3). The beads were immersed and rotated in the Con A solution for 2 h at room temperature, and 50 mM ethanolamine was used to block to residual carboxylic acid. Con A conjugated beads were stored in PBS at 4 °C.

2.11. Concentration and viral RNA extraction by Con A-column

A model system consisting of 200 mL of a solution of (a) phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, (b) 100 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM glycine, 1% beef extract, pH 9.5 (TGEB), and (c) 0.25 M glycine, 0.3 M NaCl, pH 7.5 (Glycine) with 200 μL of HuNoV (102 copies/μL) were used to investigate the qRT-PCR compatibility of HuNoV concentration by Con A-column. This was performed for each of seven genotypes of HuNoV including GI.3, GI.8, GII.2, GII.4, GII.6, GII.8, and GII.17.

A ConA-column was designed as a solid phase extraction column (SPE column) for the rapid concentration of HuNoV (GI.3, GI.8, GII.2, GII.4, GII.6, GII.8, and GII.17) from liquid samples. A syringe (10 mL Norm-Ject; Henke Sass Wolf, Germany) was packed with 3.0 g of Con A conjugated beads (0.4 – 1.2 mm diameter) and equilibrated with 10 cartridge volumes of PBS buffer. The spiked 200 mL samples were then poured through the column via gravity for 15 min at a speed of 13.5 mL/min. PBS buffer (50 mL) was sequentially added to the column from the top to remove unbound or non-specifically bound molecules. Total viral RNA was extracted using AccuPrep Viral RNA extraction kit (Bioneer) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The final elutes (50 μL) were used immediately or were stored at stored at - 80 °C for PCR assays.

2.12. Quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR assay

Primer sets that amplify a conserved region within the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene were used as previously adopted for the qRT-PCR assay [30], [31]. RT-PCR primer sets targeted the capsid protein (VP1) gene in ORF2. Sequences were compared against those listed in GenBank by using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) to ensure a high level of specificity against HuNoV. Primers used in this study are listed in Table 1 . qRT-PCR reactions were carried out in 96-well blocks with a CFX-96 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad) using a TaqMan probe mix in a reaction volume of 25.0 μL, which contained 2.0 μL of the primary cDNA reaction mixture, 2 × Ex Taq HS Mix (Takara), and the primer pair. The thermocycling condition was applied as follows: activation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by denaturation of 45 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 56 °C for 10 s and a final extension at 72 °C for 30 s. All qRT-PCR reactions were performed in biological triplicate. The threshold cycle (Ct) was automatically determined for each reaction by the CFX-96 Real-Time PCR System set with default parameters. Each qRT-PCR reaction set included a negative control of water instead of cDNA.

Table 1.

Sequences of the primers used for qRT-PCR detection of HuNoV (GI and GII).

| Geno-group | Primer | Locationa | Sequence (5′ – 3′) | Size (bp) | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI | COG1F | 5291–5310 | CGY TGG ATG CGN TTY CAT GA | 85 | M87661 |

| COG1R | 5354–5375 | CTT AGA CGC CAT CAT CAT TYA C | |||

| RING1 (a) | 5329–5349 | FAM-AGA TYG CGA TCY CCT GTC CA-BHQ | |||

| GII | JJV2F | 5003–5028 | CAA GAG TCA ATG TTT AGG TGG ATG AG | 98 | AY032605 |

| COG2R | 5081–5100 | TCG ACG CCA TCT TCA TTC AC | |||

| RING2P | 5048–5067 | FAM-TGG GAG GGC GAT CGC AAT CT-BHQ |

2.13. Recovery of HuNoV from artificially contaminated food

Locally purchased lettuce and strawberries were disinfected with UV irradiation to eliminate contaminating microorganisms. Samples of lettuce (20 g) and whole strawberries (20 g) were spiked with a 200 μL aliquot of fecal samples containing HuNoV (GII.4, 102 copies/μL). HuNoV spiked food samples were air dried for 30 min at room temperature to allow attachment of the virus. HuNoV (GII.4) from the spiked samples was eluted in 200 mL of elution buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM glycine, 1% beef extract, pH 9.5) [32]. Milk (200 mL, pasteurized at high temperatures for a short time) was also inoculated with a 200 μL aliquot of fecal samples.

Different concentration methods were performed to compare the efficiency of HuNoV recovery. For the polyethylene glycol (PEG) concentration method, the resulting supernatants (200 mL) were mixed with an equal volume of 16% (w/v) PEG 6000 (Sigma) containing 0.525 M NaCl and incubated for 16 h on ice to precipitate the viruses. The samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the pellet was re-suspended in 2 mL of sterile PBS before viral RNA extraction [30]. Virus recovery (%) was calculated as the percentage ratio between the “recovered number of HuNoV genomic copies” and the “spiked number of HuNoV genomic copies”. Three independent trials were conducted for all samples. Statistical analysis was performed using Tukey tests, and p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Interactions between HuNoV (GII.4) and Con A

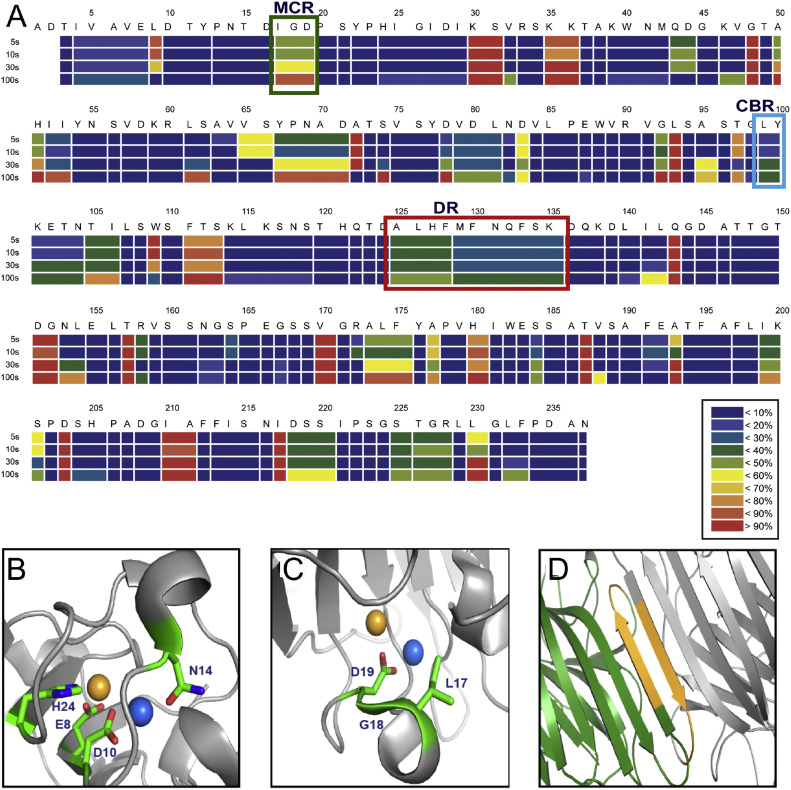

Interactions between Con A and the purified P-domain of HuNoV (GII.4) were characterized by HDX studies in order to identify putative interaction regions (Fig. 1 A and Supporting Figs. 1–3), since the GII.4 strain of HuNoV is a major cause of viral infections. Time-dependent HDX showed that the metal coordinated region (MCR), including Ile17, Gly18, and Asp19 of Con A (Fig. 1B and C), interacts with the P-domain of HuNoV (GII.4) as indicated by significant deuterium exchange alterations in this region from the Con A only and Con A-P-domain conjugated experiment. The structural analysis based on preliminary reports proposed that MCR is positioned on the outer region of Con A, and that it coordinated with metal ions including Mn2+ and Ca2+. The HDX results from Con A alone support that amino acids from Thr15 to Asp16 show high deuterium exchange rates, and Ile17 and Gly18 show to be rapidly changed starting from 5 s exposure (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). These results suggested that MCR may generate a complex between HuNoV (GII.4) and Con A. Con A have shown that hetero-metal ions are essential for the proper orientation of the key residues that mediate the carbohydrate specific interactions with hydrogen bonds, but coordination is required to control the directions of the side and main chains in Con A. Our mutational studies of MCR and CBR confirmed that metal coordination is crucial for HuNoV (GII.4) interactions (shown below). In addition to these amino acid regions, the dimerization region (DR), which is involved in dimer formation in Con A, is slow to deuterium exchange as shown in Fig. 1D [33]. The results from time-dependent HDX suggested that Con A interacts with the P-domain of HuNoV (GII.4) primarily through the MCR, because the carbohydrate binding region (CBR) of Con A, including L99, Y100, does not show significant changes in deuterium exchange rate. The HDX results provide valuable information for the understanding of interactions between Con A and HuNoV (GII.4).

Fig. 1.

Hydrogen/deuterium exchange (HDX) profile of concanavalin A (Con A), defining the interaction regions between Con A and HuNoV (GII.4). (A) Heat map at 5, 10, 30, and 100 s. Regions of the protein are highlighted as follows: the green box is the metal coordinating region (MCR); the cyan box is the carbohydrate binding region (CBR); and the red box is the dimerization region (DR). (B–D) X-ray crystallographic structure of regions of Con A (PDB accession: 3NWK). The residues of the MCR are depicted in B and C. (B) Coordination of amino acids, including Glu8, Asp10, His24, and Asp19 with metal ions (Ca2+ and Mn2+). (C) Deuterium exchanges between Ile17 and Asp19 of Con A due to the presence of the P-domain (GII.4) (D) Participation of the β-strand from Ala125 to Lys135 in the formation of a Con A dimer with the equivalent portion of another Con A monomer, forming the DR. One monomer of Con A (green) interacts with the second monomer (gray) through the β-strand (bright orange) for dimerization. Eight hydrogen bonds were detected between these two β-strands (PDB accession 1GIC).

To provide further evidence of the interaction between Con A and HuNoV (GII.4) observed by HDX-MS, the circular dichroism (CD) spectra of Con A and HuNoV (GII.4) were measured in the UV range (200–260 nm, Supporting Fig. 4). When Con A interacts with the P-domain of HuNoV (GII.4), the signal around 222 nm becomes more negative compared to that of GII.4 alone. This is because the CD spectra analysis enables the evaluation of changes in secondary structure including α-helices and β-sheets of proteins. These changes in the CD spectra indicate alterations in structure, which could result from interactions between Con A and the P-domain of HuNoV (GII.4).

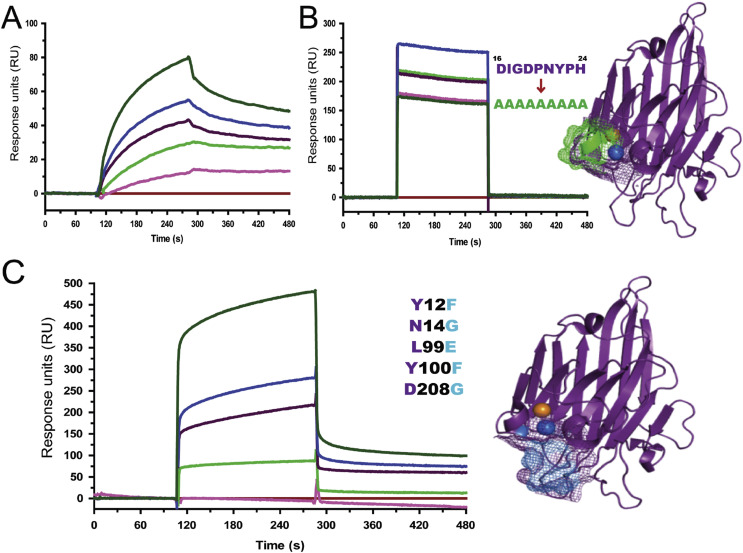

3.2. Complex generation between HuNoV (GII.4) and Con A

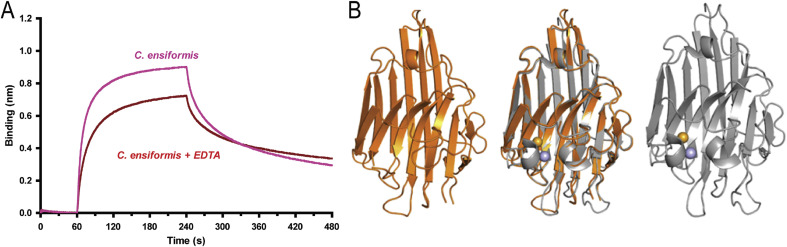

The interactions among native Con A, mutated MCR of Con A (mCon AMCR, 16DIGDPNYPH24 → 16AAAAAAAAA24) and mutated carbohydrate binding region (mCon ACBR) including Y12F, N14G, L99E, Y100F, and D208G, with HuNoV (GII.4) were measured via SPR (Fig. 2 A and C) to identify the interaction regions of Con A. The dissociation constant (KD) value indicates the interaction kinetics of an analyte and ligand; the KD values for the interaction of native Con A, mCon ACBR, and mCon AMCR with HuNoV (GII.4) were 71.5 ± 6.7 nM, 110.8 ± 7.5 nM, and 22.0 ± 17.0 μM, respectively. These values indicate that the interaction kinetics of mCon AMCR with HuNoV (GII.4) was greatly reduced compared to native Con A and mCon ACBR, suggesting that the MCR (residues 16–24) participates in the interaction with HuNoV (GII.4), whereas the CBR does not show significant changes in dissociation constant. A previous study reported that HuNoV interacts with carbohydrates [34], which suggests its binding to multiple monosaccharide moieties present in food materials. For example, glycan, a milk oligosaccharide, was reported to interact with HuNoV capsids [35]. Hydroxyl moieties in carbohydrates cause non-specific hydrogen bonding with the main and side chains of lectins [36], but the MCR of Con A was proposed as a major binding region of HuNoV (GII.4) through mutational studies. The mCon AMCR lost its binding affinity due to structural disruption of the MCR. The mutated residues of MCR and CBR in Con A (PDB accession: 3NWK) are depicted in mesh (Fig. 2B and C) [37]. In addition, apo-Con A (metal-free Con A) also showed decreased binding affinity when compared to metal-bound Con A (Fig. 3 ). This result indicates that chelating Ca2+ and Mn2+ ions with EDTA could affect the secondary structures required for specific interactions with HuNoV, which supports the involvement of the MCR in binding to HuNoV. The subtle differences in structure between metal coordinated- and apo-Con A were observed around the MCR in a superimposed image (Fig. 3B). These results proposed that metal ions coordinated through residues in the MCR were positioned properly to interact with HuNoV (GII.4), since the superimposed structures of the MCR proved that atoms from the side and main chains have different directions.

Fig. 2.

Interaction between Con A and HuNoV (GII.4). Sensograms obtained by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis using Au sensor chips with a concentration series (250, 125, 62.5, 31.3, 15.6, and 0 nM) of (A) native Con A (C. ensiformis PDB accession: 3NWK), (B) metal coordinating region (MCR)-mutated Con A (mCon AMCR), and (C) carbohydrate binding region (CBR)-mutated Con A (mCon ACBR) (n = 3, mean values). The interaction model was used to determine the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD); KD values were 71.5 ± 6.7 nM, 22.0 ± 17.0 μM, and 110.8 ± 7.5 nM for native Con A, mCon AMCR, and mCon ACBR, respectively. Mutations of Con A around the MCR and CBR are shown in (B) and (C).

Fig. 3.

Differences of binding affinity from the structures of apo-Con A and metal coordinated Con A. (A) Biolayer interferometry (BLI) assay between Con A and HuNoV (GII.4). The coordinated metal ions lost their coordination when Con A was treated with EDTA. Apo-Con A (EDTA treated Con A) loses binding affinity compared to that of wild type Con A due to the change in the environment of the metal coordinated region. (B) Metal-free Con A (apo-Con A, PDB accession 1DQ1, orange) [38], [39], superimposed images (middle), and metal coordinated Con A (holo-Con A, PDB accession 3NWK, gray) are depicted. Subtle changes were observed in the loop regions that were affected by metal coordination. Marine and orange spheres represent Mn2+ and Ca2+ ions, respectively.

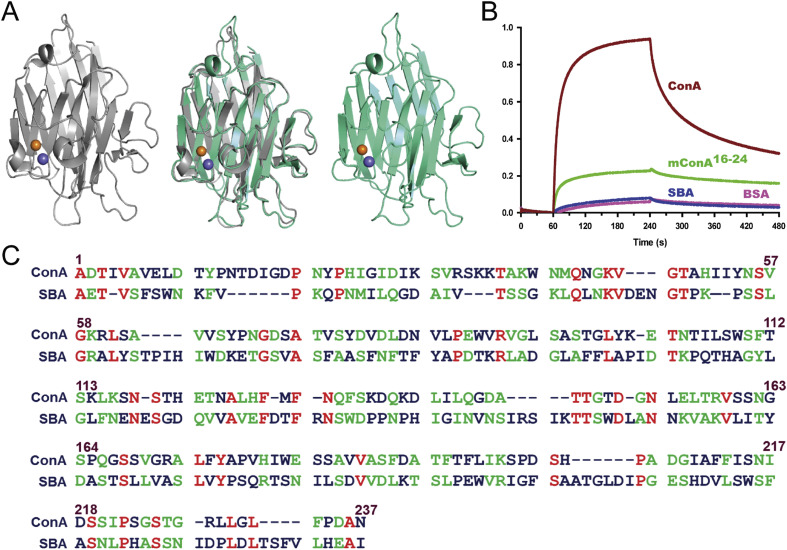

To determine the specificity of the interaction between Con A and HuNoV (GII.4), we investigated HuNoV binding with another lectin, soybean agglutinin (SBA) [38], [39], [40]. The binding affinities of Con A, SBA, and mCon AMCR were further validated as shown in Fig. 2. SBA has a high structural similarity (r.m.s. = 0.846) to Con A (Fig. 4 A); however, BLI assays demonstrated that SBA does not interact with HuNoV as shown in Fig. 4B. Results indicated that Con A had strong binding affinity, whereas mCon AMCR and SBA did not specifically interact with HuNoV (GII.4). Moreover, secondary structures including the overall loops located at the MCR and CBR are identical (PDB accession: 3NWK and 1SBD, Fig. 4A), although alignment of amino acid sequences suggested that the sequence identity between Con A and SBA is only 16% (Fig. 4C). The inability of SBA to interact with the HuNoV (GII.4) could be due to low sequence identity, despite almost identical structures. Furthermore, the MCR of Con A does not show sequence similarity to SBA. The MCR of these residues generates specific interactions with HuNoV (GII.4), because the amino acids of this site could potentially form specific secondary structures including α-helices and loops. These results indicated that the interaction between Con A and HuNoV (GII.4) is unique, in which HuNoV (GII.4) recognizes not only structural features, but also specific amino acid sequences.

Fig. 4.

High structural similarity and low sequence homology between Con A and SBA. (A) Structural alignment of Con A with SBA. Secondary structure of Con A (gray, PDB accession: 3NWK), SBA (green, PDB accession: 1SBD), and super imposed structures (middle) [37], [38], [39], [40]. (B) Sensograms representing the interaction of Con A, soybean agglutinin (SBA), and mCon AMCR with HuNoV obtained by Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI). BSA, bovine serum albumin. (C) Alignment of amino acid sequence of Con A and SBA. The highlighted green box indicates the MCR.

The ability of HuNoV (GII.4) to bind Con A compared to a commercial HuNoV antibody was examined via BLI (Supporting Fig. 5) to confirm the binding. The association between Con A and HuNoV (GII.4) was 10-fold greater than that between the HuNoV antibody and Con A, demonstrating the high binding specificity of Con A (Supporting Fig. 5). The binding ability of Con A and mutated Con A was further applied to viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) genotype IVa, an enveloped virus, in order to investigate the binding affinity with an enveloped virus (Supporting Fig. 6). The SPR results demonstrate that wtCon A has a weaker binding affinity to VHSV (KD = 710.3 ± 238.6 nM) compared with its binding affinity to HuNoV (GII.4), and that mCon ACBR has a comparably low binding specificity to VHSV (KD = 54.9 ± 26.4 μM).

3.3. Detection of HuNoV using Con A-PAB

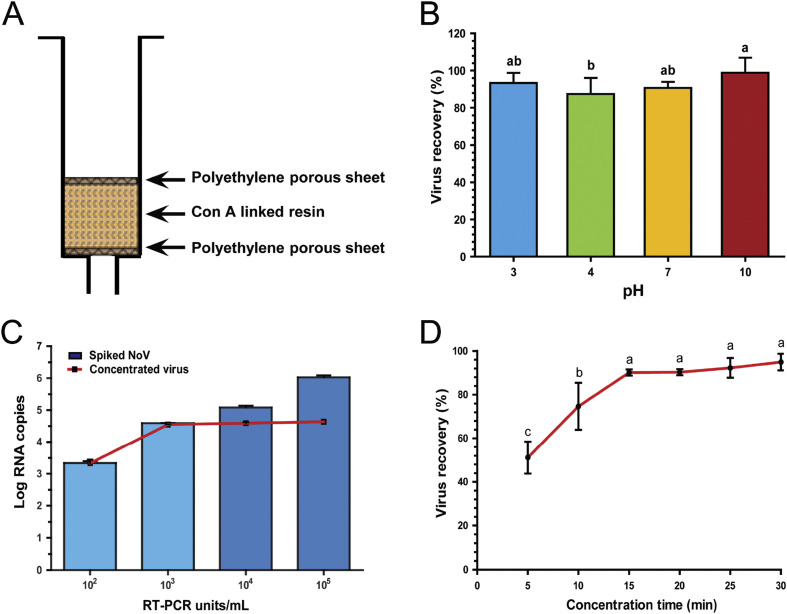

The interaction between Con A and HuNoV (GII.4) implies the potential application of Con A as a bait for HuNoV. Thus, the application of Con A to concentrate HuNoV for the rapid detection of the virus in food was tested. The conventional PEG concentration method is both time consuming and has a low sampling number, which makes it a stumbling block for the rapid analysis of HuNoV. Instead, Con A-immobilized polyacrylate beads (Con A-PAB) were developed, as explained in the methods section (Fig. 5 A), to be used in our new concentration method. The ability and stability of Con A to detect HuNoV (GII.4) was tested over pH ranges from 3 to 10 as HuNoV is usually found in contaminated foods of varying pHs (Fig. 5B). The percentage of viral recovery was not significantly affected by changes in pH, demonstrating an advantage of using Con A-PAB as a concentration tool over some of the currently available methods. This attribute is an improvement over other HuNoV detection methods that are limited to a narrow range of pH [17]. HuNoV was detected up to 101 RT-PCR units/mL, which meets the standard PCR detection level. This method was successful in recovering HuNoV (GII.4), with a virus recovery (%) of more than 77% when samples were spiked with virus concentrations ranging from 103 to 106 RT-PCR units/mL as determined by PCR (Fig. 5C). Moreover, using Con A-PAB containing 3.0 g of Con A immobilized beads, the capacity of HuNoV (GII.4) capture was up to 104 copy numbers. However, the performance of the Con A-PAB could be enhanced by increasing the amount of Con A and the surface areas of the concentration tool. Using Con A-PAB, HuNoV recovery reached more than 90% in 15 min at an eluent flow rate of 13.5 mL/min (Fig. 5D). From these initial results, we found that the stability of Con A is great for detection, and it maintains interaction with HuNoV (GII.4) in a broad range of pHs and flow-rates, suggesting that the Con A-PAB could serve as a novel concentration tool with high recovery of HuNoV (GII.4). Besides this, Con A-PAB, a method based on solid phase extraction, has other advantages, such as ease of handling several samples concurrently and speed for concentration of the virus.

Fig. 5.

Detection and recovery of HuNoV (GII.4) through Con A-PAB. (A) Modified SPE chromatography column used for the concentration of HuNoV. Recovery efficiency of spiked HuNoV (GII.4) using Con A-PAB under different (B) pHs, (C) copy numbers of virus, and (D) concentration time. All experiments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3), and different letters above the bar or line indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

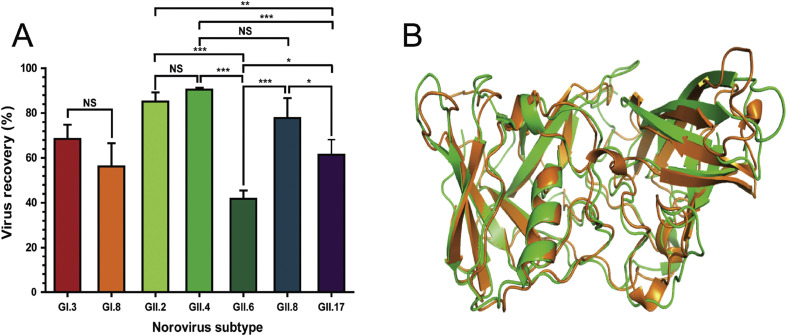

Next, the ability of Con A-PAB to interact with various genotypes of HuNoV was tested. Among seven HuNoV genogroups (GI - GVII), GI and GII, consisting of 9 and 19 genotypes, respectively, are the most common cause of human infections. The binding specificity of Con A-PAB with these genotypes was analyzed in seven samples, comprising two and five different genotypes of the GI and GII genogroups, respectively. These genotypes had varying recoveries ranging from 41.8% to 90.6% (Fig. 6 A, Supporting table 1). Among them, GII.4, which has been associated with the majority of global epidemics in the past decade [41], was recovered at the highest level (90.6%), followed by GII.2, GII.8, GII.17 and GII.6 (85.2%, 77.8%, 61.4 and 41.8% recovery, respectively). Among tested genotypes, GII.4, GII.2 and GII.6 are responsible for the majority (77.5%) of total HuNoV outbreaks in the US from 2009 to 2013 [42]. However, genotypes of GI including GI.3 and GI.8 were recovered at only 68.5% and 56.2% levels, respectively. The variability between GI and GII could be due to subtle differences in amino acid sequences between these subtypes. For example, the VP1 domains of HuNoV strains from the same genogroups have 70–90% P-domain sequence similarity; however, different genogroups have less than 50% sequence similarity [42], [43]. Superimposed structures of the P-domain of GI.8 and GII.4 show high structural similarity (r.m.s. = 1.15, Cα alignment), which may explain the ability of Con A to bind to the P-domain of both subtypes despite sequence differences (Fig. 6B). HuNoV from genogroup I shows different sequences from genogroup II, but GI.3 and GI.8 have greater than 50% recovery. The percentages of virus recovery of HuNoV from GII.2 and GII.4 were greater than 80% with the Con A-PAB when the virus copy number was higher than 103, which is sufficient to amplify the viral RNA in order to confirm HuNoV contamination in food samples. These results demonstrate that Con A-PAB can be successfully applied for the detection of HuNov (GII.2, GII.4, and GII.8) and other genotypes (GI.3, GI.8, GII.6, and GII.17).

Fig. 6.

Con A-PAB shows high recovery rate for HuNoV from different genogroups. (A) Recovery of different genotypes of genogroups I and II (GI and GII) using Con A-PAB. All experiments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3), and different letters above the bar or line indicate significant differences at p < 0.05. (B) Superimposed structures of HuNoV GI.8 (orange) and GII.4 (green) strains which show high structural similarity.

3.4. Recovery of HuNoV from food samples using Con A-PAB

The recovery of GII.4 from different food samples using Con A-PAB was compared to the recovery using the PEG precipitation method, which is usually recommended for a wide variety of viruses. Different food samples (200 mL) were spiked with 4.7 × 104 copies of HuNoV (GII.4). Tris-glycine beef extract buffer was used as an elution buffer for recovery of GII.4 from food samples [44]. The ability of Con A-PAB to concentrate the virus from different foods, such as lettuce, strawberries, and milk, was evaluated. Con A-PAB exhibited significantly higher viral recovery from lettuce compared to that of the PEG precipitation (p = 0.035). Both methods showed similar recovery from strawberries (Table 2 ). Interestingly, Con A-PAB was successful in recovering GII.4 from milk with 60.8% recovery, whereas the PEG method was not successful for this application. These results suggest that the performance of Con A-PAB is less affected by food types than PEG precipitation. Using Con A-PAB, the maximum level of HuNoV was recovered in 15 min, whereas PEG required more than 4–6 h. These results demonstrate that the use of Con A-PAB exhibits comparable viral recovery to the conventional PEG method, and enables faster concentration.

Table 2.

Comparison of recovery (%) of human norovirus (HuNoV) from different food matrices using polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation and Concanavalin A-immobilized polyacrylate beads (Con A-PAB).

| Food Sample | HuNoV recovery (%)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| PEG precipitation | Con A-PAB | |

| Milk | ND | 60.8 ± 1.7 |

| Lettuce | 71.5 ± 7.4* | 89.5 ± 11.5* |

| Strawberry | 56.1 ± 9.2 | 70.8 ± 4.3 |

Asterisks indicate significant differences between PEG and Con A-PAB determined by Student's t-test; (*p < 0.05).

ND, non-detectable.

HuNoV recovery (%) is calculated as the percentage ratio of HuNoV genomic copy number of the recovered sample to that of the spiked sample. All experiments were performed in triplicate (mean ± SD).

4. Conclusion

Biophysical assays in this study proved that Con A displayed strong interactions with HuNoV (GII.4), and these binding events were dependent on the MCR. The mutational studies of MCR and CBR proved that interaction between Con A and HuNoV are dependent on metal coordination and sequence around the MCR because SBA and apo-Con A did not show specific intractions to HuNov. These results proved that the orientations of side and main chains are critical for the generation of specific interactions with HuNoV (GII.4). A HuNoV concentration tool, Con A-PAB, was developed by adapting the simple operation principle of solid-phase extraction, which made it possible to handle multiple samples simultaneously. The tool was also capable of concentrating different GI and GII genotypes, although the viral recoveries showed variation due to their subtle differences in sequence and structure. The compatibility of the tool with PCR was demonstrated by 15 min concentration and detection of HuNoV from contaminated food samples (200 mL) using qRT-PCR. Although Con A had previously been shown to interact with enveloped viruses, this study demonstrated its potential for interaction with non-enveloped viruses (HuNoV). Despite the practical feasibility of concentrating HuNoV with Con A-PAB, the applicability of this tool should be further confirmed by competition with other non-enveloped viruses.

Grant support

This work was supported by the R&D Convergence Program of MSIP and NST of the Republic of Korea, Grant (Convergence Practical Research Project-13-4-KBSI) awarded to J.K., the Korea Basic Science Institute's Biological Disaster Analysis Research Fund (C37703) awarded to J.K., the Priority Research Centers Program through the NRF of the Republic of Korea through the MEST (Project No. 2010-0020141), and the Chonbuk National University Research Fund.

Author contributions

Duwoon K., S.J.L., and J.K. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; H.L., K.O., A.Y. K., R.A.P., Dongkyun K., J.S.C., M.J.K., S.H.K., and B.V. prepared viral samples, purified proteins, analyzed the data, and performed experiments. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.03.006.

Contributor Information

Seung Jae Lee, Email: slee026@jbnu.ac.kr.

Joseph Kwon, Email: joseph@kbsi.re.kr.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Vinje J. Advances in laboratory methods for detection and typing of norovirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53(2):373–381. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01535-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao S., Lou Z., Tan M., Chen Y., Liu Y., Zhang Z., Zhang X.C., Jiang X., Li X., Rao Z. Structural basis for the recognition of blood group trisaccharides by norovirus. J. Virol. 2007;81(11):5949–5957. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00219-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donaldson E.F., Lindesmith L.C., Lobue A.D., Baric R.S. Viral shape-shifting: norovirus evasion of the human immune system. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;8(3):231–241. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan M., Jiang X. The p domain of norovirus capsid protein forms a subviral particle that binds to histo-blood group antigen receptors. J. Virol. 2005;79(22):14017–14030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14017-14030.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan M., Jiang X. Norovirus-host interaction: implications for disease control and prevention. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2007;9(19):1–22. doi: 10.1017/S1462399407000348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kroneman A., Vega E., Vennema H., Vinje J., White P.A., Hansman G., Green K., Martella V., Katayama K., Koopmans M. Proposal for a unified norovirus nomenclature and genotyping. Arch. Virol. 2013;158(10):2059–2068. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1708-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall A.J. Noroviruses: the perfect human pathogens? J. Infect. Dis. 2012;205(11):1622–1624. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rha B., Burrer S., Park S., Trivedi T., Parashar U.D., Lopman B.A. Emergency department visit data for rapid detection and monitoring of norovirus activity, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19(8):1214–1221. doi: 10.3201/eid1908.130483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rocha-Pereira J., Neyts J., Jochmans D. Norovirus: targets and tools in antiviral drug discovery. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014;91(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel M.M., Hall A.J., Vinje J., Parashara U.D. Noroviruses: a comprehensive review. J. Clin. Virol. 2009;44(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornton A.C., Jennings-Conklin K.S., McCormick M.I. Noroviruses: agents in outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis. Disaster Manag. Res. DMR Off. Publ. Emerg. Nurses Assoc. 2004;2(1):4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dmr.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones M.K., Grau K.R., Costantini V., Kolawole A.O., de Graaf M., Freiden P., Graves C.L., Koopmans M., Wallet S.M., Tibbetts S.A., Schultz-Cherry S., Wobus C.E., Vinje J., Karst S.M. Human norovirus culture in B cells. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10(12):1939–1947. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wobus C.E., Karst S.M., Thackray L.B., Chang K.O., Sosnovtsev S.V., Belliot G., Krug A., Mackenzie J.M., Green K.Y., Virgin H.W. Replication of Norovirus in cell culture reveals a tropism for dendritic cells and macrophages. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(12):2076–2084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green J., Norcott J.P., Lewis D., Arnold C., Brown D.W.G. Norwalk-like viruses - demonstration of genomic diversity by polymerase chain-reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993;31(11):3007–3012. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.3007-3012.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikner L.A., Gerba C.P., Bright K.R. Concentration and recovery of viruses from water: a comprehensive review. Food Environ. Virol. 2012;4(2):41–67. doi: 10.1007/s12560-012-9080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melgaco F.G., Victoria M., Correa A.A., Ganime A.C., Malta F.C., Brandao M.L.L., Medeiros V.D., Rosas C.D., Bricio S.M.L., Miagostovich M.P. Virus recovering from strawberries: evaluation of a skimmed milk organic flocculation method for assessment of microbiological contamination. Int. J. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;217:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stals A., Baert L., Van Coillie E., Uyttendaele M. Extraction of food-borne viruses from food samples: a review. Int. J. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;153(1–2):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balzarini J. Targeting the glycans of glycoproteins: a novel paradigm for antiviral therapy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5(8):583–597. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrison A.R., Giomarelli B.G., Lear-Rooney C.M., Saucedo C.J., Yellayi S., Krumpe L.R.H., Rose M., Paragas J., Bray M., Olinger G.G., McMahon J.B., Huggins J., O'Keefe B.R. The cyanobacterial lectin scytovirin displays potent in vitro and in vivo activity against Zaire Ebola virus. Antivir. Res. 2014;112:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Keefe B.R., Giomarelli B., Barnard D.L., Shenoy S.R., Chan P.K.S., McMahon J.B., Palmer K.E., Barnett B.W., Meyerholz D.K., Wohlford-Lenane C.L., McCray P.B. Broad-spectrum in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy of the antiviral protein griffithsin against emerging viruses of the family coronaviridae. J. Virol. 2010;84(10) doi: 10.1128/JVI.02322-09. (vol, 84, pg, 2511, 2010) 5456–5456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bronzoni R.V., Fatima M., Montassier S., Pereira G.T., Gama N.M., Sakai V., Montassier H.J. Detection of infectious bronchitis virus and specific anti- viral antibodies using a Concanavalin A-Sandwich-ELISA. Viral. Immunol. 2005;18(3):569–578. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okino C.H., Alessi A.C., Montassier M.D.S., Rosa A.J.D., Wang X.Q., Montassier H.J. Humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to different doses of attenuated vaccine against avian infectious bronchitis virus. Viral. Immunol. 2013;26(4):259–267. doi: 10.1089/vim.2013.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyun J., Kim H.S., Kim H.S., Lee K.M. Evaluation of a new real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assay for detection of norovirus in fecal specimens. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014;78(1):40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richards G.P., Watson M.A., Kingsley D.H. A SYBR green, real-time RT-PCR method to detect and quantitate Norwalk virus in stools. J. Virol. Methods. 2004;116(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H., Li N., Xu Q., Xiao C.L., Wang H.C., Guo Z., Zhang J., Sun X.S., He Q.Y. Lipoprotein FtsB in Streptococcus pyogenes binds ferrichrome in two steps with residues Tyr137 and Trp204 as critical ligands. PLoS One. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duc N.M., Du Y., Thorsen T.S., Lee S.Y., Zhang C., Kato H., Kobilka B.K., Chung K.Y. Effective application of bicelles for conformational analysis of G protein-coupled receptors by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. J. Am. Mass. Spectr. 2015;26(5):808–817. doi: 10.1007/s13361-015-1083-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S.Y., Giladi M., Bohbot H., Hiller R., Chung K.Y., Khananshvili D. Structure-dynamic basis of splicing-dependent regulation in tissue-specific variants of the sodium-calcium exchanger. FASEB J. 2016;30(3):1356–1366. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-282251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emmenegger C.R., Brynda E., Riedel T., Sedlakova Z., Houska M., Alles A.B. Interaction of blood plasma with antifouling surfaces. Langmuir. 2009;25(11):6328–6333. doi: 10.1021/la900083s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shoulaifar T.K., DeMartini N., Ivaska A., Fardim P., Hupa M. Measuring the concentration of carboxylic acid groups in torrefied spruce wood. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;123:338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jothikumar N., Lowther J.A., Henshilwood K., Lees D.N., Hill V.R., Vinje J. Rapid and sensitive detection of noroviruses by using TaqMan-based one-step reverse transcription-PCR assays and application to naturally contaminated shellfish samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71(4):1870–1875. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.4.1870-1875.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kageyama T., Kojima S., Shinohara M., Uchida K., Fukushi S., Hoshino F.B., Takeda N., Katayama K. Broadly reactive and highly sensitive assay for Norwalk-like viruses based on real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41(4):1548–1557. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.4.1548-1557.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Senousy W.M., Costafreda M.I., Pinto R.M., Bosch A. Method validation for norovirus detection in naturally contaminated irrigation water and fresh produce. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013;167(1):74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kantardjieff K.A., Hochtl P., Segelke B.W., Tao F.M., Rupp B. Concanavalin A in a dimeric crystal form: revisiting structural accuracy and molecular flexibility. Acta Cryst. D. 2002;58(5):735–743. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901019588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morton V., Jean J., Farber J., Mattison K. Detection of noroviruses in ready-to-eat foods by using carbohydrate-coated magnetic beads. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75(13):4641–4643. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00202-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shang J., Piskarev V.E., Xia M., Huang P.W., Jiang X., Likhosherstov L.M., Novikova O.S., Newburg D.S., Ratner D.M. Identifying human milk glycans that inhibit norovirus binding using surface plasmon resonance. Glycobiology. 2013;23(12):1491–1498. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwt077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders D.A.R., Moothoo D.N., Raftery J., Howard A.J., Helliwell J.R., Naismith J.H. The 1.2 angstrom resolution structure of the Con A-dimannose complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;310(4):875–884. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foroughi L.M., Kang Y.N., Matzger A.J. Polymer-induced heteronucleation for protein single crystal growth: structural elucidation of bovine liver catalase and Concanavalin A forms. Cryst. Growth. Des. 2011;11(4):1294–1298. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bezerra G.A., Oliveira T.M., Moreno F.B., de Souza E.P., da Rocha B.A., Benevides R.G., Delatorre P., de Azevedo W.F., Jr., Cavada B.S. Structural analysis of Canavalia maritima and Canavalia gladiata lectins complexed with different dimannosides: new insights into the understanding of the structure-biological activity relationship in legume lectins. J. Struct. Biol. 2007;160(2):168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouckaert J., Dewallef Y., Poortmans F., Wyns L., Loris R. The structural features of concanavalin A governing non-proline peptide isomerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275(26):19778–19787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001251200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olsen L.R., Dessen A., Gupta D., Sabesan S., Sacchettini J.C., Brewer C.F. X-ray crystallographic studies of unique cross-linked lattices between four isomeric biantennary oligosaccharides and soybean agglutinin. Biochemistry. 1997;36(49):15073–15080. doi: 10.1021/bi971828+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lim K.L., Hewitt J., Sitabkhan A., Eden J.S., Lun J., Levy A., Merif J., Smith D., Rawlinson W.D., White P.A. A multi-site study of norovirus molecular epidemiology in Australia and New Zealand, 2013-2014. PLoS One. 2016;11(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vega E., Barclay L., Gregoricus N., Shirley S.H., Lee D., Vinje J. Genotypic and epidemiologic trends of norovirus outbreaks in the United States, 2009 to 2013. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52(1):147–155. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02680-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hutson A.M., Atmar R.L., Estes M.K. Norovirus disease: changing epidemiology and host susceptibility factors. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12(6):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanchez G., Elizaquivel P., Aznar R. A single method for recovery and concentration of enteric viruses and bacteria from fresh-cut vegetables. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012;152(1–2):9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.