Abstract

Mitochondria are intracellular organelles that oxidize nutrients, make ATP, and fuel eukaryotic life. Their energy providing function is directly dependent on enzymes and coenzymes contained within the organelle. Perhaps, the most important coenzymes for energy yielding reactions are the pyridine nucleotides NAD(H) and NADP(H). Both aerobic and anaerobic metabolism rely on the electron carrying properties of pyridine nucleotides to regulate energy production. The intracellular NAD+/NADH ratio controls the rate of ATP synthesis by regulating flux through NAD(H)-linked dehydrogenases and by activating NAD+ dependent enzymes that post-translationally modify proteins. Thus, mitochondrial energy transduction pathways can be substantially mediated by NAD+; as an electron carrier exerting control over dehydrogenase enzymes or by activating enzymes that affect protein modification. The importance of this is highlighted in the explosion of recent studies linking impaired NAD+ metabolism to human health and disease. Most notably, studies linking changes in NAD+ availability or altered NAD+/NADH ratio to derangements in metabolic and cellular energy transduction processes. In this review, we focus on the most recent investigative efforts to identify the role NAD+ plays in modulating mitochondrial function and also summarize the current knowledge describing the therapeutic application of elevating NAD+ levels via pharmacologic and genetic approaches to treat human disease.

Introduction

Mammalian cells manage their energetic need by continuously adapting their intermediary metabolism to changes in their environment. When energetic need is high or cellular ATP levels low; cells respond by stimulating catabolic processes that oxidize organic nutrients for ATP production. Nutrients, such as glucose, amino acids, and fatty acids are broken down in enzymatic steps to remove electrons and transfer them to soluble electron carriers, such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) [1,2]. Oxidized NAD (NAD+) is the main hydride acceptor in intermediary metabolism and is crucial for sustaining bioenergetics in the cell [3]. The cycling between NAD+ and its reduced form NADH in reduction–oxidation (redox) reactions is critical for multiple steps of glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Eukaryotes keep ATP levels relatively constant by modulating intermediary metabolism to match nutrient availability and energetic demand. NAD(H) can serve as an energy sensor that links nutrient availability, cellular energy status, and ATP production.

Three families of enzymes consume NAD+ as co-substrate: 1) sirtuin deacylases, 2) ADP-ribose transferases, and 3) cyclic ADP-ribose synthases. These enzymes are sensitive to the abundance of NAD+ in the cell and regulate intermediary metabolism through post-translational modification (PTM) of metabolic enzymes. For example, the sirtuin deacylase enzymes target and regulate a multitude of transcription factors and enzymes involved in mitochondrial biogenesis, TCA cycle, amino acid metabolism, fatty acid oxidation (FAO), and OXPHOS [4]. Therefore, cells require a continuous supply of NAD+ for energy transduction to proceed. Eukaryotes have devised numerous pathways to obtain, synthesize, and cycle NAD(H) to meet this demand. Mammalian cells continually salvage NAD+ from its end product nicotinamide (NAM) or synthesize it from essential NAD+ precursors obtained from the diet as described in section 2 below.

NAD+ biosynthesis: de novo and salvage pathways

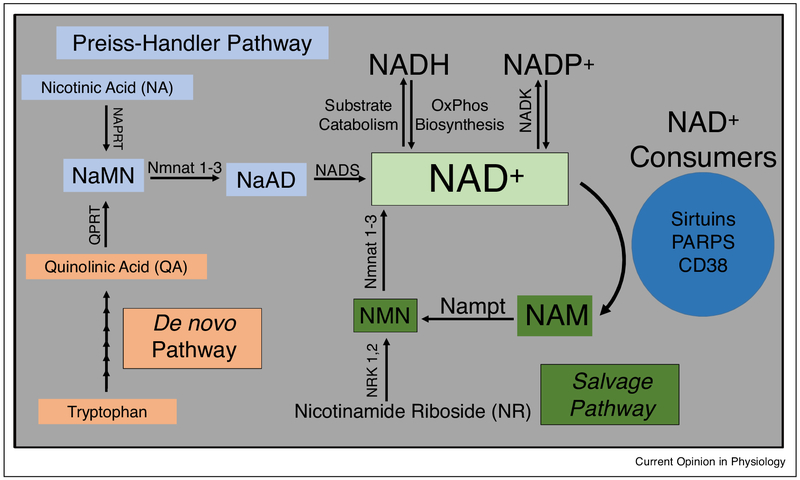

Synthesis of NAD+ occurs via two main pathways in mammals; a de novo pathway and a salvage pathway (Figure 1) [5]. NAD+ is also continually interconverted into other pyridine nucleotides. It can be reduced to NADH and can be phosphorylated by NAD kinase to form NADP+ [6]. Each pathway starts with a different building block or root component. Tryptophan derived quinolinic acid (QA) is the major starting component for the de novo pathway in eukaryotes. In the salvage pathway, NAD+ can be regenerated from NAM, nicotinic acid (NA), or nicotinamide riboside (NR). NAM is converted into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt). NMN can also be generated by the phosphorylation of NR by nicotinamide riboside kinase (NRK). Both NaMN and NMN are then adenylylated by nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyl transferases NMNATs to NAD+.

Figure 1.

NAD+ metabolism pathways in mammals. NAD+ is consumed by enzymatic processes into nicotinamide (NAM). In the Salvage pathway NAM is converted into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT). The NMN is converted to NAD+ by nicotinamide mononucleotide adenyltransferase (Nmnat) 1–3. Alternatively, nicotinamide riboside (NR) can be phosphorylated by nicotinamide riboside kinase (NRK) 1 or 2 to form NMN. NAD+ can also be generated from nicotinic acid (NA) in the Preiss-Handler pathway. NA is converted to nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NaMN) by nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase (NAPRT). NaMN can also be formed in the de novo pathway from tryptophan derived quinolinic acid (QA). Quinolinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase (QPRT) catalyzes the reaction of QA to NaMN. Nmnat 1–3 then convert NaMN to nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (NaAD) which is further produced into NAD+ by the enzyme NAD synthase (NADS).

NAD(H) in intermediary metabolism

The NAD(H) pool is central to the extent at which redox reactions in intermediary metabolism proceed (reviewed here [7]). Table 1 outlines some of the key enzymatic reactions in substrate metabolism that are sensitive to NAD+/NADH ratio [7,8]. For example, the NAD+/NADH ratio controls the flux of glucose metabolism through: firstly, glycolytic enzymes in the cytosol catalyzing pyruvate production, secondly, the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH) which oxidizes pyruvate into acetyl-CoA, and thirdly, mitochondrial enzymes in the TCA cycle and respiratory chain.

Table 1.

NAD(H)-linked dehydrogenases in intermediary metabolism.

| Enzyme name | Subcellular location |

Metabolic pathway | NAD+/NADH regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 1 (BDH1) | Mitochondria | Ketone body synthesis/oxidation | Low ratio favors ketone synthesis and high ratio ketone oxidation [15] |

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase | Mitochondria nucleus [8] | TCA Cycle | High ratio favors NADH generation for ATP production [7] |

| α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase | Mitochondria | TCA Cycle | High ratio favors NADH generation for ATP production [7] |

| Malate dehydrogenase | Mitochondria, cytosol, nucleus [8] | TCA Cycle and NAD(H) shuttle | High ratio favors NADH generation for ATP production [7] |

| Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Cytosol | Lipid synthesis and NAD (H) shuttle | Regenerates NAD+ from NADH [7] |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase | Mitochondria nucleus [8] | Links glycolysis to TCA cycle | Low ratio inactivates enzyme slowing conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA [7] |

| 3-OH acyl-CoA dehydrogenase | Mitochondria | Fatty acid oxidation | Low ratio inhibits Fatty Acid Oxidation [7] |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | Cytosol, nucleus [8] | Anaerobic metabolism | Low ratio favors conversion of pyruvate to lactate [7] |

| Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Cytosol, nucleus [8] | Glycolysis | High ratio favors glycolysis to proceed [7] |

NADH carries and donates electrons (reducing equivalents) to Complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) in the mitochondrial respiratory chain to drive ATP production. Oxidation of NADH by Complex I is a major site of aerobic NAD+ regeneration in the cell. It has been suggested the rate of NADH oxidation for energy transduction may be proportional to the amount bound to intracellular protein [9]. NAD(H) and NADP(H) exist both bound and un-bound to protein and are heavily compartmentalized within the cell [9,10]. This organization is critical for maintaining cellular redox state and for biochemical processes to proceed. Thus, cells rely on specific redox shuttles to transfer reducing equivalents across intracellular membranes. The cytosolic and mitochondrial subcellular NAD(H) pools are linked by glycolysis, glycerol-3-phosphate, and malate-aspartate shuttles. The compartmentation and bound versus un-bound pools of NAD(H) are crucial for cellular metabolism but complicate accurate analysis of redox state and NAD(H) determination. To date, most measurements have been made at the tissue level without subcellular fractionation and have utilized destructive techniques [11,12]. This is a challenge in the field as discussed in ‘Challenges and opportunities’ section.

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) must have continuous supply of NAD+ for its catalytic activity and for glycolysis to proceed. In anaerobic conditions, NADH can be re-oxidized to NAD+ by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) [6,7]. The lactate generated can enter the bloodstream for delivery to the liver where LDH converts it back to pyruvate for glucose production in gluconeogenesis as an energy source. These reactions represent the Cori cycle.

ß-oxidation of fatty acids generates acetyl-CoA in the mitochondrial matrix for use in the TCA cycle. l-3-hydroxyacyl CoA dehydrogenase, the third enzyme in the FAO pathway, is linked to and regulated by the NAD+/NADH ratio. FAO enzymes are also regulated by NAD+-dependent deacylation reactions that can increase or decrease FAO depending on energy status and type of tissue as discussed in section 4 [13,14].

Ketone synthesis/oxidation depends on the cellular NAD (H) pool. A key enzyme in both processes, β-hydroxy-butyrate dehydrogenase (BDH1), requires NADH to convert acetoacetate to ²-hydroxybutyrate (²-OHB) in hepatic mitochondria [15,16]. ²-OHB produced in the liver can be distributed via the bloodstream to metabolically active tissue (i.e. muscle and brain) where ²-OHB is converted back to acetoacetate by BDH1. Acetoacetate is utilized to generate acetyl-CoA for ATP production in extra hepatic tissue. The direction of the BDH1 reaction is directly proportional to the mitochondrial NAD+/NADH ratio (this reaction is also often used to determine the mitochondrial redox state as described in ‘Challenges and opportunities’ section) It should be mentioned, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarly-CoA synthase 2 (HMGCS2), the rate limiting enzyme in ketone body synthesis, is also regulated by NAD+-dependent deacylase reactions [15,17].

Distinct from catabolism, biosynthetic reactions in the cytosol, such as fatty acids or cholesterol biosynthesis, require NADPH generated from pentose phosphate pathway and are hence regulated by NADP/NADPH ratio [5,7].

NAD+ consuming reactions

NAD+ is consumed and metabolized to nicotinamide by three families of enzymes: 1) sirtuin deacylases, 2) ADP-ribose transferases, and 3) cyclic ADP-ribose synthases [5,18]. Aberrant activity of these enzymes could alter the NAD(H) pool and consequently any NAD(H) dependent reactions. On the other hand, decreased NAD+ availability due to either impaired NAD biosynthetic/salvage pathway or NAD+/NADH redox imbalance could profoundly affect the reactions catalyzed by the enzymes described here.

Sirtuins

The sirtuins are a family of seven proteins (Sirt1-7) that so far have been found to exhibit deacetylase, demalonylase, desuccinylase, and deglutarylase acitivity [19,20]. Reversible protein lysine deacetylation has been the most studied sirtuin modification and a growing list of deacetylation targets for sirtuins have been described. Lysine acetylation/deacetylation is considered to be a major control point for many enzymes but there does remain some challenges to be addressed. The issue of site occupancy and stoichiometry are important in determining the biological significance of lysine acetylation sites on regulating enzyme activity [21,22]. The fraction of protein that is modified (stoichiometry) needs to be determined in order to accurately interpret if the acetylation/deacetylation modification regulates a particular enzyme [22]. It also remains to be determined whether all types of acylation lead to similar functional changes.

Sirtuin activity is connected to the metabolic state of the cell. Deacetylation or deacylation by sirtuins requires NAD+ as a co-substrate. Nutrient deprivation and/or decline in cellular energy status has been shown to activate Sirt1 to increase oxidative metabolism for energy production [23]. Sirt1 deacetylates peroxisome proliferatior-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α) to enhance its activity and trigger downstream signaling pathways that can increases FAO, mitochondrial biogenesis, gluconeogenesis, and inhibit glycolysis [24–26]. Observations made in the past few years suggested that sirtuin activity could be affected by the NAD+/NADH ratio [27]. This notion is provocative and controversial as a recent report shows that NADH can inhibit sirtuin activity in vitro but the level of NADH required for inhibition is likely beyond the physiological range [28]. Thus, measurements of NAD(H) level in live cells would be critical to further elucidate the matter.

Three sirtuin isoforms (Sirt3, Sirt4, and Sirt5) are localized to mitochondria [29]. Loss of mitochondria localized Sirt3 results in hyperacetylation of mitochondrial proteins with lowered FAO and ATP production [13,30]. The first reported mitochondrial protein to be regulated by Sirt3 catalyzed deacetylation was acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 (AceCS2) [31,32]. It was shown that Lys642 was deacetylated by Sirt3 to activate AceCS2 during prolonged starvation for energy production. AceCS2 converts acetate into acetyl-CoA for ATP production. Sirt3 also deacetylates Lys42 on long-chain acyl CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) thereby stimulating FAO and improving ATP production in liver of mice fed a high fat diet (HFD) [13]. In contrast, Alrob et al. [14] showed HFD increased acetylation of LCAD in the heart and lowered Sirt3 expression causing an increase in FAO and inhibition of glucose oxidation. The authors attribute the increased FAO to the acetylation and activation of LCAD and β-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (β-HAD). Koentges et al. [33] found Sirt3 knockout (Sirt3KO) mice to have decreased palmitate and glucose oxidation with impaired ATP synthesis. Obviously, Sirt3 plays a role in metabolic flexibility that may be tissue specific. Jing et al. demonstrated PDH activity to be inhibited in skeletal muscle of Sirt3KO mice that induces a switch from carbohydrate oxidation to a reliance on fatty acid utilization [34]. The group of Zhao et al. also found enzymes in FAO to be activated by acetylation in liver tissue [35]. Sirt3 also regulates ketone body production by deacetylating HMGCS2 [17]. Sirt3 has also been shown to deacetylate and increase enzymatic activity of isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (Idh2) [36] and succinate dehydrogenase subunit A (SDHA) [37] in the TCA cycle. A recent report [38•] identified a homeostatic mechanism by which mitochondrial stress causes the release of sequestered Sirt3 from ATP synthase to target and deacetylate mitochondrial enzymes involved in nutrient oxidation, such as the TCA enzyme α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, thereby linking mitochondrial stress, NAD metabolism, and nutrient oxidation. Sirt3 also targets and deacetylates NDUFA9 subunit of complex I in the respiratory chain to maintain basal ATP levels [30].

Sirt5KO mice exhibit hypersuccinylation in the heart with diminished FAO and decreased ATP production. Sirt5 regulates FAO by activating enoyl-CoA hydratase α (ECHA) by desuccinylation of Lys351 [39]. Hershberger et al. [40] recently found Sirt5KO mice to have decreased NAD+/NADH ratio with lower rates of FAO, glucose oxidation, and reduced survival from transverse aortic constriction (TAC) surgery. Sirt5 has also been shown to control and regulate pyruvate metabolism by decreasing PDH activity [41], ketone body formation by increasing the activity of HMGCS2, and the urea cycle by deacetylating carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) [42].

Sirt4 has been shown to have a role in regulating lipid metabolism. Sirt4 deacetylates Lys471 on malonyl CoA decarboxylase (MCD) to lower its activity, promote lipid anabolism, and inhibit FAO [43]. Other reports for SIRT4KO mice have demonstrated increased insulin secretion, glutamine metabolism, and dysregulated leucine metabolism [44].

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs)

PARPs are a family of 17 ADP-ribosyl transferases that catalyze mono or poly (ADP-ribosylation). PARPs play a large role in DNA repair and are a major consumer of NAD+ in the cell [5]. PARP1-KO mice have higher mitochondrial content and are protected against HFD induced metabolic disease [45]. In a different study, PARP1 was shown to regulate the activity of hexokinase which initiates glycolysis by converting glucose into glucose-6-phosphate. PARP1 inhibits hexokinase activity suppressing glycolysis and depleting ATP levels [46,47].

Cyclic ADP-ribose synthases

Cyclic ADP-ribose synthases produce cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) and consume NAD+. cADPR is potent second messenger in calcium and insulin signaling [48]. Mice lacking CD38 have increased NAD+ content in muscle, brain, liver, and heart tissue and increased Sirt1 activity. Overexpression of CD38 in 293T cells results in a decline in NAD+ levels, lowered mitochondrial respiration, and a dependence on glycolysis [49•]. Further, in this study deletion of CD38 protected against age associated declines in NAD+ levels and improved mitochondrial respiration in aged mice. CD38 knockout mice are also protected against diet-induced obesity and inhibitors of CD38 also increase NAD+ levels in the liver with higher levels of FAO and protect against metabolic disease [48].

Pathology and therapeutic application

There are a growing number of metabolic and age-related diseases linked to impaired NAD+ homeostasis and decline in mitochondrial function. Findings from preclinical studies would indicate elevation of NAD+ levels to be a promising intervention to treat these diseases. For example, aging, obesity, cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury, and cardiomyopathy, all diminish NAD+ availability [48,50,51••]. Nampt is known to be downregulated at the protein and mRNA level in cardiac stress, aging, and obesity related diseases. Adipocyte-specific deletion of Nampt results in multi-organ insulin resistance in mice that can be rescued with NMN supplementation [52]. Heterozygous Nampt deficient mice also demonstrate impaired insulin secretion that can be rescued with NMN [53]. Increasing NAD+ level by NR supplementation to mice can also improve insulin sensitivity and protect against diet-induced obesity [54]. In this study, NR increased tissue NAD+ levels and boosted oxidative metabolism. NR was also effective at preventing the development of adult mitochondrial myopathy in mice. In this study, NR induced mitochondrial biogenesis and increased oxidative metabolism [55].

Overexpressing Nampt in skeletal muscle results in a 50% increase in muscle NAD+ levels but does not increase mitochondrial biogenesis or protect from the metabolic consequences of HFD [56]. Deletion of Nampt in skeletal muscle severely reduces NAD+ levels and impairs ATP production [57••]. The diminished intermuscular ATP content leads to deficits in skeletal muscle function in aged mice. Administering NR restores ATP production and rescues the age related decline in skeletal muscle function. Aging is associated with a decline in skeletal muscle stem cell function and diminished ability to regenerate damaged muscle fibers [58]. The stem cells rely on glycolysis for energy and therefore need continuous supply of NAD+ for their continued function. A recent study showed benefit of NR supplementation in rejuvenating muscle stem cells in aged mice and in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy [59••]. The study suggested that NR restored NAD+ levels needed for the mitochondrial unfolded protein response; thereby improving mitochondrial respiration, membrane potential, and ATP production in the muscle stem cells.

Cardiac stress also induces changes in Nampt protein expression and NAD+ levels [50]. Acute ischemia results in lower NAD+/NADH ratio and diminished NAD+ levels in cardiac tissue and in mitochondria [60]. Furthermore, cardiac ischemia-reperfusion (IR) injury downregulated Nampt mRNA and protein expression [50]. Cardiac specific overexpression of Nampt markedly increased NAD+ levels in the heart and protected from cardiac IR injury [61]. It appears the elevated NAD+ levels stimulate autophagy to improve quality control of proteins and increase ATP levels. Pre-treating mice with NMN is effective at preventing the NAD+ decline associated with ischemia and protects from cardiac IR [62]. Cardiac hypertrophy is also associated with changes in NAD+ homeostasis. Pillai et al. [63] showed loss of intracellular NAD+ levels in a mouse model of Angiotensin II induced cardiac hypertrophy. NAD+ administration activated Sirt3 and blocked the agonist-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Declines in the NAD+/NADH ratio due to impaired ETC function has also been shown to increase mitochondrial protein acetylation and predispose mice to cardiac hypertrophy and failure. NAD+ redox imbalance and increased protein acetylation was found in heart tissue from mice and human patients in advanced staged heart failure [64••]. Importantly, NMN normalized the NAD+ redox imbalance, suppressed pathologic hypertrophy, and improved cardiac function in the failing mouse hearts. Similarly, cardiac specific overexpression of Nampt increased NAD+, increased flux through the malate-aspartate shuttle (MAS), and improved myocardial energetics in hypertrophied hearts. Martin et al. recently demonstrated the efficacy of NMN in restoring cardiac function and improving cardiac energetics in a genetic mouse model of cardiomyopathy [65]. Findings in this study suggest the benefits of elevating NAD+ levels for the treatment of cardiomyopathy are dependent on Sirt3. Diminished NAD+ levels and increased mitochondrial protein acetylation was also found in human patients with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy [51••]. This study by Horton et al. provide intriguing evidence that perturbed NAD+ homeostasis occurs only in decompensated HF. Cardiac NAD+ levels were unchanged in the heart of mice 4 weeks after TAC (compensated HF) but a severe decline was found in mice subjected to TAC combined with myocardial infarction (decompensated). Both the human and mouse HF samples had increased lysine acetylation on proteins involved in mitochondrial energy transduction pathways; including FAO, TCA, and ETC. Succinate dehydrogenase A (SDHA) was found to be hyperacetylated in the HF samples with lowered activity and suppressed complex II driven mitochondrial respiration [51••].

Challenges and opportunities

Clearly, derangements in NAD+ metabolism contribute to impairment in mitochondrial fuel oxidation, mitochondrial number, and capacity for ATP synthesis. Maintenance of the NAD(H) pool is central to regulation of intermediary metabolism, ATP production, and other biological functions. These findings have potential for translation as multiple compounds are available as NAD precursor or Nampt activator [66]. However, manipulation of the NAD(H) pool for therapy does have some challenges as discussed below.

The two most heavily studied NAD precursors, NR and NMN, have mostly been used in murine models of disease at very high doses (~500 mg/kg). Two recent human studies have shed light on the pharmacokinetics (PK) of orally administered NR and its ability to raise NAD levels at tolerable doses [67•,68]. Airhart et al. [67•] treated 8 healthy human volunteers for 9 days with oral NR. Days 1 and 2 the volunteers received 250 mg dose of NR then up to a peak dose of 1000 mg twice daily by day 9. The NR significantly increased steady-state, whole-blood NAD levels in all participants without any adverse effects. In a separate study, Trammell et al. [68] treated 12 healthy human subjects at three different single oral dose levels of NR (30 mg, 100 mg, and 1000 mg). The NR increased peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) NAD levels in 12 human subjects. The doses evaluated in these two human studies are much lower than those used in murine disease models. The next step will be to determine if these doses are effective at treating human disease. At the time of writing this manuscript there are 16 human clinical trials listed for NR on www.clinicaltrials.gov website.

The intracellular NAD(H) pool is compartmentalized. The cytosolic and mitochondrial subcellular pools are linked by glycolysis, glycerol-3-phosphate, and malateaspartate shuttles. Currently, it is unclear how disease or interventions (genetic or pharmacologic) impact the separate pools. This is mainly due to lack of proper tools to directly assess NAD(H) in the separate compartments. Further, distinguishing between the total concentration of NAD(H), the amount bound to protein, and the free concentration in the cytosol and mitochondria has been difficult [11,12]. Most current biochemical assays are destructive and the sample preparation likely affects accurate determination. Williamson et al. designed an elegant method to estimate the NAD+/NADH ratio in each compartment. This method uses the principle of chemical equilibrium for metabolites generated by LDH for the cytosol and BDH1 for mitochondria [69]. But this method requires tissue to be homogenized and may not reflect the in vivo state. New genetic NAD+ or NAD+/NADH sensors have the potential to define how disease and interventions affect each of these distinct subcellular NAD(H) pools in vivo [70–72]. Animal model bearing these indicators in specific subcellular compartment will be extremely valuable. Magnetic resonance based technology is also being developed to non-invasively determine in vivo concentration of NAD(H) [73]. It is also worth mentioning that all the preclinical studies reported so far used a ‘prevention’ approach, that is, the NAD(H) pool was expanded before or at the same time of injury. For clinical application, it would be more relevant to test the efficacy of a treatment in diseased subjects, that is, increasing the NAD(H) pool after the pathological changes have been developed. This type of study will advance our understanding for both mechanisms and efficacy in a scenario relevant for therapy, thus, critical for translation.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

This work is supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL110349 and HL126209 to RT, and T32 HL007828 to MW).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Kolwicz SC Jr, Purohit S, Tian R: Cardiac metabolism and its interactions with contraction, growth, and survival of cardiomyocytes. Circ Res 2013, 113:603–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR, Folmes CD, Jaswal JS, Stanley WC: Myocardial fatty acid metabolism in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2010, 90:207–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belenky P, Bogan KL, Brenner C: NAD+ metabolism in health and disease. Trends Biochem Sci 2007, 32:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verdin E, Hirschey MD, Finley LW, Haigis MC: Sirtuin regulation of mitochondria: energy production, apoptosis, and signaling. Trends Biochem Sci 2010, 35:669–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houtkooper RH, Canto C, Wanders RJ, Auwerx J: The secret life of NAD+: an old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocrine Rev 2010, 31:194–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura M, Bhatnagar A, Sadoshima J: Overview of pyridine nucleotides review series. Circ Res 2012, 111:604–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ussher JR, Jaswal JS, Lopaschuk GD: Pyridine nucleotide regulation of cardiac intermediary metabolism. Circ Res 2012, 111:628–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boukouris AE, Zervopoulos SD, Michelakis ED: Metabolic enzymes moonlighting in the nucleus: metabolic regulation of gene transcription. Trends Biochem Sci 2016, 41:712–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blinova K, Carroll S, Bose S, Smirnov AV, Harvey JJ, Knutson JR, Balaban RS: Distribution of mitochondrial NADH fluorescence lifetimes: steady-state kinetics of matrix NADH interactions. Biochemistry 2005, 44:2585–2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Nowaczyk K, Johnson ML: Fluorescence lifetime imaging of free and protein-bound NADH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89:1271–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klingenberg M, Buecher T: Biological oxidations. Annu Rev Biochem 1960, 29:669–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun F, Dai C, Xie J, Hu X: Biochemical issues in estimation of cytosolic free NAD/NADH ratio. PLoS ONE 2012, 7:e34525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Goetzman E, Jing E, Schwer B, Lombard DB, Grueter CA, Harris C, Biddinger S, Ilkayeva OR, Stevens RD et al. : Sirt3 regulates mitochondrial fatty-acid oxidation by reversible enzyme deacetylation. Nature 2010, 464:121–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alrob OA, Sankaralingam S, Ma C, Wagg CS, Fillmore N, Jaswal JS, Sack MN, Lehner R, Gupta MP, Michelakis ED, Padwal RS et al. : Obesity-induced lysine acetylation increases cardiac fatty acid oxidation and impairs insulin signalling. Cardiovasc Res 2014, 103:485–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman JC, Verdin E: Beta-hydroxybutyrate: a signaling metabolite. Annu Rev Nutr 2017, 37:51–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krebs HA, Gascoyne T: The redox state of the nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotides in rat liver homogenates. Biochem J 1968, 108:513–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Hua L, Dittenhafer-Reed KE, Schwer B, Lombard DB, Li Y, Bunkenborg J, Alt FW, Denu JM, Jacobson MP et al. : Sirt3 deacetylates mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coa synthase 2 and regulates ketone body production. Cell Metab 2010, 12:654–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blander G, Guarente L: The sir2 family of protein deacetylases. Annu Rev Biochem 2004, 73:417–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frye RA: Characterization of five human cdnas with homology to the yeast sir2 gene: Sir2-like proteins (sirtuins) metabolize NAD and may have protein adp-ribosyltransferase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1999, 260:273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frye RA: Phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic sir2-like proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000, 273:793–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baeza J, Dowell JA, Smallegan MJ, Fan J, Amador-Noguez D, Khan Z, Denu JM: Stoichiometry of site-specific lysine acetylation in an entire proteome. J Biol Chem 2014, 289:21326–21338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baeza J, Smallegan MJ, Denu JM: Mechanisms and dynamics of protein acetylation in mitochondria. Trends Biochem Sci 2016, 41:231–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canto C, Auwerx J: Targeting sirtuin 1 to improve metabolism: all you need is NAD(+)? Pharmacol Rev 2012, 64:166–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puigserver P, Wu Z, Park CW, Graves R, Wright M, Spiegelman BM: A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 1998, 92: 829–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P: Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of pgc-1alpha and sirt1. Nature 2005, 434:113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardie DG: Amp-activated/snf1 protein kinases: conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nat Rev Molec Cell Biol 2007, 8:774–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karamanlidis G, Lee CF, Garcia-Menendez L, Kolwicz SC Jr, Suthammarak W, Gong G, Sedensky MM, Morgan PG, Wang W, Tian R: Mitochondrial complex I deficiency increases protein acetylation and accelerates heart failure. Cell Metab 2013, 18:239–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madsen AS, Andersen C, Daoud M, Anderson KA, Laursen JS, Chakladar S, Huynh FK, Colaco AR, Backos DS, Fristrup P, Hirschey MD et al. : Investigating the sensitivity of NAD+-dependent sirtuin deacylation activities to NADH. J Biol Chem 2016, 291:7128–7141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lombard DB, Alt FW, Cheng HL, Bunkenborg J, Streeper RS, Mostoslavsky R, Kim J, Yancopoulos G, Valenzuela D, Murphy A, Yang Y et al. : Mammalian sir2 homolog sirt3 regulates global mitochondrial lysine acetylation. Molec Cell Biol 2007, 27: 8807–8814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahn BH, Kim HS, Song S, Lee IH, Liu J, Vassilopoulos A, Deng CX, Finkel T: A role for the mitochondrial deacetylase sirt3 in regulating energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105:14447–14452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hallows WC, Lee S, Denu JM: Sirtuins deacetylate and activate mammalian acetyl-coa synthetases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103:10230–10235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwer B, Bunkenborg J, Verdin RO, Andersen JS, Verdin E: Reversible lysine acetylation controls the activity of the mitochondrial enzyme acetyl-coa synthetase 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103:10224–10229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koentges C, Pfeil K, Schnick T, Wiese S, Dahlbock R, Cimolai MC, Meyer-Steenbuck M, Cenkerova K, Hoffmann MM, Jaeger C, Odening KE et al. : Sirt3 deficiency impairs mitochondrial and contractile function in the heart. Basic Res Cardiol 2015, 110:36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jing E, O’Neill BT, Rardin MJ, Kleinridders A, Ilkeyeva OR, Ussar S, Bain JR, Lee KY, Verdin EM, Newgard CB, Gibson BW et al. : Sirt3 regulates metabolic flexibility of skeletal muscle through reversible enzymatic deacetylation. Diabetes 2013, 62: 3404–3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao S, Xu W, Jiang W, Yu W, Lin Y, Zhang T, Yao J, Zhou L, Zeng Y, Li H, Li Y et al. : Regulation of cellular metabolism by protein lysine acetylation. Science (New York, NY) 2010, 327:1000–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Someya S, Yu W, Hallows WC, Xu J, Vann JM, Leeuwenburgh C, Tanokura M, Denu JM, Prolla TA: Sirt3 mediates reduction of oxidative damage and prevention of age-related hearing loss under caloric restriction. Cell 2010, 143:802–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cimen H, Han MJ, Yang Y, Tong Q, Koc H, Koc EC: Regulation of succinate dehydrogenase activity by sirt3 in mammalian mitochondria. Biochemistry 2010, 49:304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.•.Yang W, Nagasawa K, Munch C, Xu Y, Satterstrom K, Jeong S, Hayes SD, Jedrychowski MP, Vyas FS, Zaganjor E, Guarani V et al. : Mitochondrial sirtuin network reveals dynamic sirt3-dependent deacetylation in response to membrane depolarization. Cell 2016, 167 985–1000.e1021.This study provides a comprehensive mitochondrial sirtuin interactome/network to further define substrates for mitochondrial localized sirtuins. A major finding of the study was sirtuin 3 (Sirt3) associating with OSCP subunit of ATP Synthase (ATP5O) in a pH and mitochondrial membrane potential sensitive manner. Depolarization of mitochondria using CCCP treatment decreased global acetylation in mitochondria from WT hearts but not in mitochondria from Sirt3 deficient mouse hearts. Yang et al. hypothesize a pool of mitochondrial Sirt3 binds ATP Synthase under normal conditions, but loss of membrane potential or mitochondrial stress causes Sirt3 to be released from ATP Synthase to deacetylate target proteins to restore mitochondrial health. The authors theorize this may be a mechanism for cells to maintain mitochondrial membrane potential homeostasis and a means of rapid deacetylation of mitochondrial proteins during stress.

- 39.Sadhukhan S, Liu X, Ryu D, Nelson OD, Stupinski JA, Li Z, Chen W, Zhang S, Weiss RS, Locasale JW, Auwerx J et al. : Metabolomics-assisted proteomics identifies succinylation and sirt5 as important regulators of cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113:4320–4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hershberger KA, Abraham DM, Martin AS, Mao L, Liu J, Gu H, Locasale JW, Hirschey MD: Sirtuin 5 is required for mouse survival in response to cardiac pressure overload. J Biol Chem 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park J, Chen Y, Tishkoff DX, Peng C, Tan M, Dai L, Xie Z, Zhang Y, Zwaans BM, Skinner ME, Lombard DB et al. : Sirt5-mediated lysine desuccinylation impacts diverse metabolic pathways. Molec Cell 2013, 50:919–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakagawa T, Lomb DJ, Haigis MC, Guarente L: Sirt5 deacetylates carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 and regulates the urea cycle. Cell 2009, 137:560–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laurent G, German NJ, Saha AK, de Boer VC, Davies M, Koves TR, Dephoure N, Fischer F, Boanca G, Vaitheesvaran B, Lovitch SB et al. : Sirt4 coordinates the balance between lipid synthesis and catabolism by repressing malonyl coa decarboxylase. Molec cell 2013, 50:686–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson KA, Huynh FK, Fisher-Wellman K, Stuart JD, Peterson BS, Douros JD, Wagner GR, Thompson JW, Madsen AS, Green MF, Sivley RM et al. : Sirt4 is a lysine deacylase that controls leucine metabolism and insulin secretion. Cell Metab 2017, 25 838–855.e815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bai P, Canto C, Oudart H, Brunyanszki A, Cen Y, Thomas C, Yamamoto H, Huber A, Kiss B, Houtkooper RH, Schoonjans K et al. : Parp-1 inhibition increases mitochondrial metabolism through sirt1 activation. Cell Metab 2011, 13:461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andrabi SA, Umanah GKE, Chang C, Stevens DA, Karuppagounder SS, Gagné J-P, Poirier GG, Dawson VL, Dawson TM: Poly(adp-ribose) polymerase-dependent energy depletion occurs through inhibition of glycolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111:10209–10214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fouquerel E, Goellner Eva M, Yu Z, Gagné J-P, Barbi de Moura M, Feinstein T, Wheeler D, Redpath P, Li J, Romero G, Migaud M et al. : Artd1/parp1 negatively regulates glycolysis by inhibiting hexokinase 1 independent of NAD+ depletion. Cell Rep 2014, 8:1819–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Canto C, Menzies KJ, Auwerx J: Nad(+) metabolism and the control of energy homeostasis: A balancing act between mitochondria and the nucleus. Cell Metab 2015, 22:31–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.•.Camacho-Pereira J, Tarrago MG, Chini CCS, Nin V, Escande C, Warner GM, Puranik AS, Schoon RA, Reid JM, Galina A, Chini EN: Cd38 dictates age-related NAD decline and mitochondrial dysfunction through an sirt3-dependent mechanism. Cell Metab 2016, 23:1127–1139.Camacho-Pereira et al. demonstrate increased protein expression and activity level of the NADase CD38 in aged mice. The aged mice also exhibited a decline in NAD+ level with mitochondrial dysfunction (diminished mitochondrial respiration). NAD+ level and mitochondrial function were preserved in aged CD38 knockout mice providing evidence that CD38 is important in the age related altered NAD+ homeostasis and mitochondrial dysfunction. Similar to the aged mouse study, Camacho-Pereira et al. also found older human subjects (average age 61) to have increased mRNA expression levels of CD38 in adipose tissue compared to younger human subjects (average age 34).

- 50.Hsu CP, Yamamoto T, Oka S, Sadoshima J: The function of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase in the heart. DNA Repair 2014, 23:64–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.••.Horton JL, Martin OJ, Lai L, Riley NM, Richards AL, Vega RB, Leone TC, Pagliarini DJ, Muoio DM, Bedi KC Jr, Margulies KB et al. : Mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation in the failing heart. JCI Insight 2016, 2.Analysis of cardiactissue samples from human patients with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy revealed diminished NAD+ levels and increased mitochondrial protein acetylation. These changes were also observed in mice subjected to pressure overload surgery with apical myocardial infarction. Proteomics studies of both human and mouse heart samples demonstrated an increase in lysine acetylation on proteins involved in mitochondrial energy transduction including enzymes in fatty acid oxidation, tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), electron transport chain (ETC), andoxidative phosphorylation. Hyperacetylation of succinate dehydrogenase A of TCA and Complex II of ETC was found in both human and mice heart failure samples with reduced activity level.

- 52.Stromsdorfer KL, Yamaguchi S, Yoon MJ, Moseley AC, Franczyk MP, Kelly SC, Qi N, Imai S, Yoshino J: Nampt-mediated NAD(+) biosynthesis in adipocytes regulates adipose tissue function and multi-organ insulin sensitivity in mice. Cell Rep 2016, 16:1851–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Revollo JR, Korner A, Mills KF, Satoh A, Wang T, Garten A, Dasgupta B, Sasaki Y, Wolberger C, Townsend RR, Milbrandt J et al. : Nampt/pbef/visfatin regulates insulin secretion in beta cells as a systemic NAD biosynthetic enzyme. Cell Metab 2007, 6:363–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Canto C, Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Youn DY, Oosterveer MH, Cen Y, Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Yamamoto H, Andreux PA, Cettour-Rose P, Gademann K et al. : The NAD(+) precursor nicotinamide riboside enhances oxidative metabolism and protects against high-fat diet-induced obesity. Cell Metab 2012, 15:838–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khan NA, Auranen M, Paetau I, Pirinen E, Euro L, Forsstrom S, Pasila L, Velagapudi V, Carroll CJ, Auwerx J, Suomalainen A: Effective treatment of mitochondrial myopathy by nicotinamide riboside, a vitamin b3. EMBO Molec Med 2014, 6:721–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frederick DW, Davis JG, Davila A Jr, Agarwal B, Michan S, Puchowicz MA, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Baur JA: Increasing NAD synthesis in muscle via nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase is not sufficient to promote oxidative metabolism. J Biol Chem 2015, 290:1546–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.••.Frederick DW, Loro E, Liu L, Davila A Jr, Chellappa K, Silverman IM, Quinn WJ 3rd, Gosai SJ, Tichy ED, Davis JG, Mourkioti F et al. : Loss of NAD homeostasis leads to progressive and reversible degeneration of skeletal muscle. Cell Metab 2016, 24:269–282.Muscle-specific deletion of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), the rate limiting enzyme in NAD+ salvage pathway, results in severe intramuscular NAD+ depletion, impaired mitochondrial function, and reduced muscle ATP content. The disruption in NAD+ homeostasis leads to muscle fiber degeneration and loss of muscle strength and endurance. Administering nicotinamide riboside (NR) restored mitochondrial function and ATP content in the NAMPT deficient muscle. This prevented the development of muscle dysfunction and fiber degeneration in the muscle specific NAMPT knockout mice.

- 58.Guarente L: Cell metabolism. The resurgence of NAD(+). Science (New York, NY) 2016, 352:1396–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.••.Zhang H, Ryu D, Wu Y, Gariani K, Wang X, Luan P, D’Amico D, Ropelle ER, Lutolf MP, Aebersold R, Schoonjans K et al. : Nad(+) repletion improves mitochondrial and stem cell function and enhances life span in mice. Science (New York, NY) 2016, 352:1436–1443.Zhang etal. demonstrate the decline in NAD+ levels in muscle stem cells blunts the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmito) and contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction. Treating aged mice with nicotinamide riboside (NR) increased muscle stem cell NAD+ levels and increased expression of tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation genes. NR treated stem cells also had increases in mitochondrial respiration, membrane potential, and ATP levels. Stem cell numbers increased with the NR treatments and the aged mice displayed enhanced muscle function. Elevating the stem cell NAD+ level improved mitochondrial homeostasis, protected the muscle stem cells, and improved muscle function associated with aging in mice.

- 60.Di Lisa F, Menabo R, Canton M, Barile M, Bernardi P: Opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore causes depletion of mitochondrial and cytosolic NAD+ and is a causative event in the death of myocytes in postischemic reperfusion of the heart. J Biol Chem 2001, 276:2571–2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hsu CP, Oka S, Shao D, Hariharan N, Sadoshima J: Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase regulates cell survival through NAD+ synthesis in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 2009, 105: 481–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamamoto T, Byun J, Zhai P, Ikeda Y, Oka S, Sadoshima J: Nicotinamide mononucleotide, an intermediate of NAD+ synthesis, protects the heart from ischemia and reperfusion. PLoS ONE 2014, 9:e98972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pillai VB, Sundaresan NR, Kim G, Gupta M, Rajamohan SB, Pillai JB, Samant S, Ravindra PV, Isbatan A, Gupta MP: Exogenous NAD blocks cardiac hypertrophic response via activation of the sirt3-lkb1-amp-activated kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 2010, 285:3133–3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.••.Lee CF, Chavez JD, Garcia-Menendez L, Choi Y, Roe ND, Chiao YA, Edgar JS, Goo YA, Goodlett DR, Bruce JE, Tian R: Normalization of NAD+ redox balance as a therapy for heart failure. Circulation 2016, 134:883–894.NAD+ redox imbalance and increased protein acetylation was found in heart tissue from mice and human patients in advanced staged heart failure. The hyperacetylation of mitochondrial proteins increased the sensitivity of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in mitochondria. Administering nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) normalized the NAD+ redox imbalance, suppressed pathologic hypertrophy, and improved cardiac function in the failing mouse hearts. Cardiac specific overexpression of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt) increased NAD+, increased flux through the malate-aspartate shuttle (MAS), and improved myocardial energetics in hypertrophied hearts.

- 65.Martin AS, Abraham DM, Hershberger KA, Bhatt DP, Mao L, Cui H, Liu J, Liu X, Muehlbauer MJ, Grimsrud PA, Locasale JW et al. : Nicotinamide mononucleotide requires sirt3 to improve cardiac function and bioenergetics in a friedreich’s ataxia cardiomyopathy model. JCI Insight 2017, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang W, Karamanlidis G, Tian R: Novel targets for mitochondrial medicine. Sci Transl Med 2016, 8:326rv323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.•.Airhart SE, Shireman LM, Risler LJ, Anderson GD, Nagana, Gowda GA, Raftery D, Tian R, Shen, O’Brien KD: An openlabel, non-randomized study of the pharmacokinetics of the nutritional supplement nicotinamide riboside (nr) and its effects on blood NAD+ levels in healthy volunteers. PLOS ONE 2017, 12:e0186459.Non-randomized, open-label pharmacokinetics (PK) study of 8 healthy human volunteers who received 250 mg nicotinamide riboside (NR) orally on Days 1 and 2, then a peak dose of 1000 mg twice daily on days 7 and 8. On Day 9, subjects were administered a single oral dose of 1000 mg NR followed by a 24-h PK study. Oral NR was well tolerated with no adverse events with significant increases in blood NR concentration. The NR dose of 1000 mg twice daily significantly increased steady-state, whole-blood levels of NAD+ in all study participants with individual increases ranging from 35 to 168% above baseline NAD+ levels.

- 68.Trammell SA, Schmidt MS, Weidemann BJ, Redpath P, Jaksch F, Dellinger RW, Li Z, Abel ED, Migaud ME, Brenner C: Nicotinamide riboside is uniquely and orally bioavailable in mice and humans. Nat Commun 2016, 7:12948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williamson DH, Lund P, Krebs HA: The redox state of free nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of rat liver. Biochem J 1967, 103:514–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cambronne XA, Stewart ML, Kim D, Jones-Brunette AM, Morgan RK, Farrens DL, Cohen MS, Goodman RH: Biosensor reveals multiple sources for mitochondrial NAD(+). Science (New York, NY) 2016, 352:1474–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhao Y, Hu Q, Cheng F, Su N, Wang A, Zou Y, Hu H, Chen X, Zhou HM, Huang X, Yang K et al. : Sonar, a highly responsive NAD+/NADH sensor, allows high-throughput metabolic screening of anti-tumor agents. Cell Metab 2015, 21:777–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao Y, Wang A, Zou Y, Su N, Loscalzo J, Yang Y: In vivo monitoring of cellular energy metabolism using sonar, a highly responsive sensor for NAD(+)/NADH redox state. Nat Protoc 2016, 11:1345–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhu XH, Lu M, Lee BY, Ugurbil K, Chen W: In vivo NAD assay reveals the intracellular NAD contents and redox state in healthy human brain and their age dependences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112:2876–2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]