Abstract

SARS coronavirus continues to cause sporadic cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in China. No active or passive immunoprophylaxis for disease induced by SARS coronavirus is available. We investigated prophylaxis of SARS coronavirus infection with a neutralising human monoclonal antibody in ferrets, which can be readily infected with the virus. Prophylactic administration of the monoclonal antibody at 10 mg/kg reduced replication of SARS coronavirus in the lungs of infected ferrets by 3·3 logs (95% Cl 2·6–4·0 logs; p<0·001), completely prevented the development of SARS coronavirus-induced macroscopic lung pathology (p=0·013), and abolished shedding of virus in pharyngeal secretions. The data generated in this animal model show that administration of a human monoclonal antibody might offer a feasible and effective prophylaxis for the control of human SARS coronavirus infection.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) has emerged as a frequently fatal respiratory-tract infection caused by the newly identified SARS coronavirus. After the worldwide SARS epidemic in 2002–2003, sporadic cases continue to arise in southern China, possibly because of human contact with the animal reservoir.1 Two recent cases of laboratory- acquired SARS coronavirus infections in China spread into the community and triggered extensive efforts in tracing and isolating contacts of patients to prevent a new epidemic. Means to control SARS coronavirus infection through active or passive immunisation are, therefore, urgently needed.

Passive transfer of mouse immune serum has been shown to reduce pulmonary viral titres in mice infected with SARS coronavirus.2 Immunoprophylaxis of SARS coronavirus infection with human monoclonal antibodies might therefore be a viable strategy to control SARS.

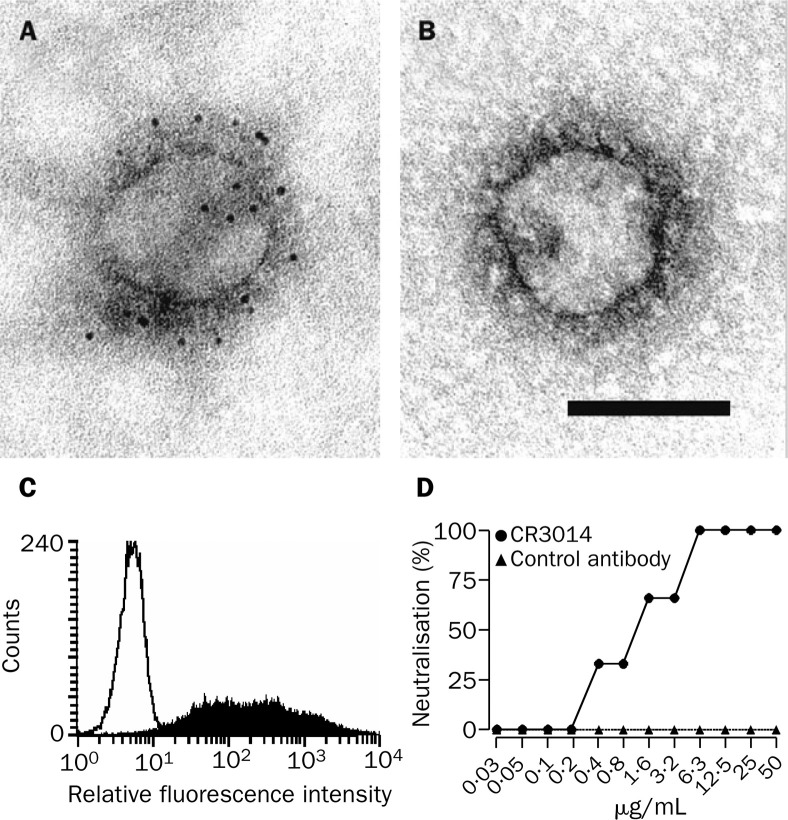

We generated a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody, CR3014, reactive with whole inactivated SARS corona- virus, by antibody phage display technology screening a large naive antibody library. Binding of this antibody to the viral peplomers was visualised by electron microscopy with indirect two-step immunogold labelling. SARS coronavirus from the supernatant of infected Vero cells was adsorbed to copper grids coated with carbon and Pioloform, which were incubated with the monoclonal antibodies by floating on droplets for 30 min at room temperature. Bound monoclonal antibodies were detected by incubation on droplets of anti-human-IgG-gold-5 nm conjugates (British Biocell, Cardiff, UK). The grids were negative contrasted with 1% uranyl acetate and assessed with a ZEISS EM 10 A transmission electron microscope (figure 1A, 1B ). CR3014 was shown to react with the cell-surface expressed spike glycoprotein of SARS coronavirus: HEK293T cells were transfected with the plasmid-expressed, codon-optimised full-length glycoprotein spike, and stained with CR3014 and an R-phycoerythrin-labelled second antibody after 48 h using standard procedures for FACS-analysis (figure 1C). CR3014 was also shown to neutralise SARS coronavirus in vitro: triplicate wells of Vero cells were infected with 100 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infective dose) of SARS coronavirus strain HK-39849, and pre-incubated for 1 h at 37°C with different concentrations of CR3014 or control antibody. The presence or absence of a cytopathic effect was scored in each well on day 5 after infection, and the percentage of protected wells was noted (figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Binding of CR3014 monoclonal antibody to viral peplomers of SARS coronavirus (A, B) and to HEK293T cells expressing glycoprotein spike of SARS coronavirus (C), and in vitro neutralisation of SARS coronavirus strain HK-39849 (D)

Incubation with CR3014 led to a dense gold-label of the outer peplomer region of SARS coronavirus strain Frankfurt 1 (A), whereas a control human IgG1 monoclonal antibody did not induce any label (B). Bar indicates 100 nm. (C) Filled histogram=glycoprotein spike of SARS coronavirus, strain Frankfurt 1. Open histogram=control plasmid.

We tested the in-vivo potency of this antibody in ferrets, because these animals can be readily infected with SARS coronavirus by the intratracheal route, replicate the virus to high titres in the lung, and develop macroscopic and microscopic lung lesions.3 Experimental infection of ferrets with human respiratory viruses, including influenza viruses, is common practice, therefore procedures to work with these animals under the biocontainment conditions required for SARS coronavirus are well established. Approval for animal experiments was obtained from the institutional animal welfare committee.

In the first set of experiments, ferrets (Mustela furo, female, weight 800–900 g) were infected intratracheally with either 103 TCID50 or 104 TCID50 (n=8 for each group) of SARS coronavirus strain HKU-39849, which had been preincubated in 1 mL of cell-culture medium at 37°C for 1 h with either CR3014 or an human IgG1 control monoclonal antibody (n=4 for each group). The concentration of antibody in the medium was a 20-fold excess of the concentration theoretically needed for neutralisation of the challenge dose (0·13 mg/mL for the lower and 1·3 mg/mL for the higher challenge dose). Pharyngeal swabs were taken from the animals before challenge and on days 2, 4, and 7 after challenge, and frozen at –70°C before being subjected to quantitative RT- PCR. Two animals from each of the four groups were killed on days 4 and 7 and necropsies were done according to a standard protocol. For assessment of lung inflammation associated with SARS coronavirus infection, haematoxylineosin-stained sections from the cranial and caudal parts of the lung were examined for inflammatory foci by light microscopy with a 10× objective. For measurement of the SARS coronavirus titre, homogenates were prepared from 0·1–0·3 g of lung tissue pooled from cranial, medial, and caudal parts of the lung.

All control ferrets had high titres of SARS coronavirus in their lungs on day 4, and lower titres on day 7. Viral replication was accompanied by multifocal pulmonary lesions affecting about 5–10% of the surface area of the lung. Hislologically lesions consisled mainly of mild alveolar damage as well as peribronchial and perivascular lymphocyte infiltration. RT-PCR on pharyngeal swabs showed that virus was shed in the throal throughout day 7. Animals exposed to the mixture of virus and CR3014 had almost undetectable titres of SARS coronavirus in the lung, showed no lung lesions on day 4 or 7, and did not shed SARS coronavirus in their throats.

In the second set of experimenls, two groups of ferrets (n=4 in each group) received an intraperitoneal injection of either CR3014 or the control antibody at a concentration of 10 mg/kg, 24 h before intratracheal infection with 104 TCID50 SARS coronavirus, strain HKU-39849. Venous blood was drawn before administration of monoclonal antibody, before challenge, and on day 2 after the challenge. We measured the human IgG1 content of the serum by ELISA, and the neutralising capacity by a neutralisation assay using the fixed virus-varying serumdilution format. Pharyngeal swabs were taken from the animals before the inoculation and on days 2 and 4 after the challenge for quantitative RT-PCR. All animals were killed on day 4 and lung samples were taken as described for the first set of experiments.

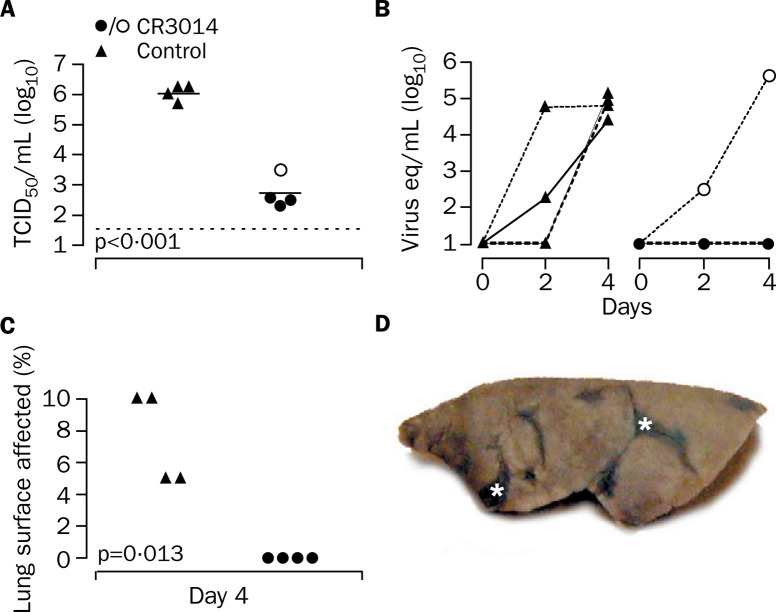

The mean SARS coronavirus titre in lung homogenates of the animals given CR3014 was 3·3 logs lower than that of the control animals (95% CI 2·6–4·0 logs, p<0·001 [Student's t test]; figure 2A ). This difference was accompanied by complete protection from macroscopic lung pathology (p=0·013 [Wilcoxon rank-sum test]; figure 2C) and a reduction of microscopic lesions compared with controls, which all showed multifocal lesions on gross necropsy (figure 2D). Shedding of SARS coronavirus in the throat was completely abolished in three of the four animals treated with CR3014 (figure 2B). However, in one animal the level of SARS coronavirus excretion was similar to that noted in the control group. The concentration of CR3014 in the serum of this ferret before challenge was less than 5 μg/mL, compared with 65–84 μg/mL in the other three animals, suggesting inappropriate antibody administration. Neutralising serum titres in this animal were less than half of those in the other animals on day 0 (titre of 5 against 100 TCID50), and were not detectable on day 2 after infection, compared with a titre of 5–10 against 100 TCID50 in the other animals on day 2.

Figure 2.

SARS coronavirus replication in lung tissue (A), shedding of SARS coronavirus in pharyngeal secretions (B), and macroscopic lung pathology (C,D) in ferrets

(A) SARS coronavirus titres in lung homogenates on day 4 after challenge shown as TCID50/mL. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. Dotted line shows lower detection limit of assay.(B) SARS coronavirus excretion measured by RT-PCR in pharyngeal swabs expressed as SARS coronavirus equivalents (eq), which equal TCID50. One animal in the CR3014 group, indicated by open circles, shed virus. (C) All CR3014-treated ferrets were free from macroscopic lung pathology, whereas all control ferrets showed multifocal lesions. (D) Left formalin-fixed lung (inflated with formalin by intrabronchial intubation)of a control ferret, with multifocal lesions (asterisks).

SARS coronavirus has been detected in nasopharyngeal aspirates of up to 72% of SARS patients, being associated with increased mortality, and in the lungs of all autopsied patients by viral isolation or RT-PCR.4 On the basis of our data and the successful prophylaxis of respiratory syncytial virus disease with a humanised monoclonal antibody (Palivizumab), we reason that immunoprophylaxis of SARS coronavirus infection with a human monoclonal antibody might be an option for the control of SARS.5 The prophylactic dose we used for CR3014 (10 mg/kg) is less than the 15 mg/kg dose at which Palivizumab is given intramuscularly to at-risk infants once a month. If CR3014 reduced the replication of SARS coronavirus in people to the same extent as in ferrets, and in view of the serum halflife of up to 20 days for IgG1 in human beings, one intramuscular administration of CR3014 at the dose used in this study should protect an adult for the length of at least one to two SARS coronavirus incubation periods (median 4–6 days). Passive immunisation with CR3014 might, therefore, be a feasible approach to prevent lung manifestations in people exposed to SARS coronavirus, and prevent person-to-person spread of the virus by abolishment of viral shedding in pharyngeal secretions.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

SARS coronavirus strain HKU-39849 was provided by Malik Peiris, Department of Microbiology, University of Hong Kong. We thank Geert van Amerongen and Roberto Dias d'Ullois for technical support in the animal studies, and Frank Pistoor (ViroClinics), James Simon (CoroNovative), and Jindrich Cinatl for logistical support of the studies. We thank Rob van Lavieren, Freek Cox, Mandy Jongeneelen, Gabi Bauer, and Andrea Mannel for excellent technical assistance.

Contributors

J ter Meulen, A B H Bakker, G J Weverling, J Goudsmit, and A D M E Osterhaus planned the study, analysed data, and wrote the report. E N van den Brink, J de Kruif, W Preiser, and W Spaan generated and characterised the recombinant antibody. H R Gelderblom did electron microscopy. B E E Martina and B L Haagmans did animal experiments and virus titrations. T Kuiken did pathological analysis. All authors saw and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The animal studies at the Erasmus University, Rotterdam, were funded by Crucell Holland BV. The sponsor was involved in the design of the animal studies and in data analysis, but was not involved in performing the animal studies or the virological or pathological analysis of the necropsy samples.

References

- 1.Guan Y, Zheng BJ, He YQ. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in Southern China. Science. 2003;302:276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subbarao K, McAuliffe J, Vogel L. Prior infection and passive transfer of neutralizing antibody prevent replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in the respiratory tract of mice. J Virol. 2004;78:3572–3577. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3572-3577.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martina BE, Haagmans BL, Kuiken T. SARS virus infection in cats and ferrets. Nature. 2003;425:915. doi: 10.1038/425915a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsang OT, Chau TN, Choi KW. Coronavirus-positive nasopharyngeal aspirate as predictor for severe acute respiratory syndrome mortality. Emerg lnf Dis. 2003;9:1381–1387. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.030400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parnes C, Guillermin J, Habersang R. Palivizumab prophylaxis of respiratory syncytial virus disease in 2000–2001: results from The Palivizumab Outcomes Registry. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;35:484–489. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]