Abstract

Background

New York area hospitals were hit hard by the swine influenza (H1N1) pandemic in spring and summer 2009. During a pandemic, the initial cases may be difficult to recognize, but subsequent clinical diagnoses were relatively straightforward, given the high volume of cases and their typical clinical presentation. Swine influenza pneumonia presents as an influenza-like illness (ILI) with dry cough, fever >102°F and myalgias. A variety of other viral pneumonias, eg, cytomegalovirus, human parainfluenza virus 3 (HPIV 3), and adenovirus, as well as bacterial community-acquired pneumonias (CAPs) that may present with some of the clinical and laboratory features of H1N1 pneumonia. Most adults admitted to hospitals with ILIs during the pandemic had, in fact, definite or probable H1N1 pneumonia. The Infectious Disease Division at Winthrop-University Hospital developed a diagnostic weighted point score to identify probable H1N1 cases in hospitalized adults with rapid negative influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs).

Methods

We present a case of an elderly male who presented with an ILI and negative RIDTs during the H1N1 pandemic. He was admitted with a diagnosis of possible H1N1, and placed on influenza precautions and oseltamivir. Although the patient had features consistent with H1N1 pneumonia, Legionnaires' disease was included in the differential diagnosis because of his elevated serum ferritin levels. A Legionella urinary antigen test was positive for Legionella pneumophila (serogroups 01-06).

Results

The peak seasonal incidence of sporadic Legionnaires' disease occurs in the summer and fall. Even in the midst of a pandemic, clinicians should be on the alert for other infectious diseases that may mimic H1N1 pneumonia. In our experience, the best way to differentiate H1N1 from ILIs or other bacterial CAPs is through the Winthrop-University Hospital Infectious Disease Division's diagnostic weighted point score system for H1N1 pneumonia or its rapid simplified version, ie, the diagnostic swine influenza triad. Legionnaires' disease is the atypical CAP pathogen most likely to mimic H1N1 pneumonia.

Conclusions

Based on this and other nine cases at our institution during the “herald wave” of pandemic, we conclude that Legionnaires' disease may mimic swine influenza (H1N1) pneumonia.

The swine influenza (H1N1) pandemic originated in Mexico and rapidly spread to the United States. New York was the epicenter of the pandemic in the United States in late spring and summer 2009.1, 2 Initially, the problem was to differentiate and identify H1N1 from other influenza-like illnesses (ILIs). Because H1N1 is a variant of influenza A, rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) for influenza A were used to screen for influenza A in hopes of identifying H1N1 before the definitive results of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) were available. Unfortunately, RT-PCR testing by the health department was restricted, making laboratory-based diagnoses impossible.3 To compound the diagnostic difficulties, the H1N1 pandemic occurred while other respiratory viruses were still circulating in the community, including early seasonal human influenza A. Therefore, physicians had to differentiate H1N1 from human seasonal influenza A, as well as from other respiratory viruses presenting as ILIs.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 As the pandemic progressed into the summer, pneumonia attributable to other respiratory viruses and human influenza were no longer detectable in the community. By July, many patients presenting with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) admitted to Winthrop-University Hospital's Emergency Department (ED) had H1N1 pneumonia.4, 11 We present a case of Legionnaires' disease mimicking H1N1 pneumonia, admitted in the midst of the “herald wave” of the H1N1 pandemic in early summer.

Case Report

A 62-year-old man presented at the ED with complaints of fever, chills, weakness, and malaise for 3 to 4 days. The patient also complained of vomiting, diarrhea, and dry cough. He denied any recent or close sick contacts or recent travel. The patient had no known drug allergies. In the ED, he had a temperature of 103°F, with a heart rate of 87/minutge, and his respiratory rate was 20/minute. On physical examination, he had right lower-lobe rales. The remainder of his physical examination was unrevealing, except for an irregular pulse and a faint, nonradiating (2/6) systolic murmur.

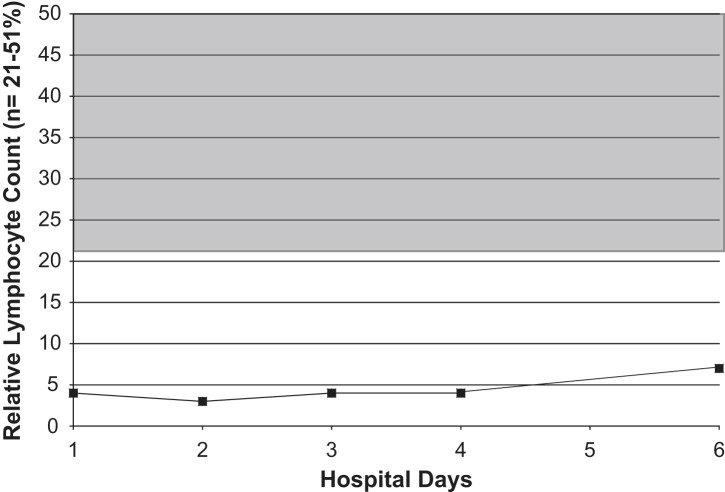

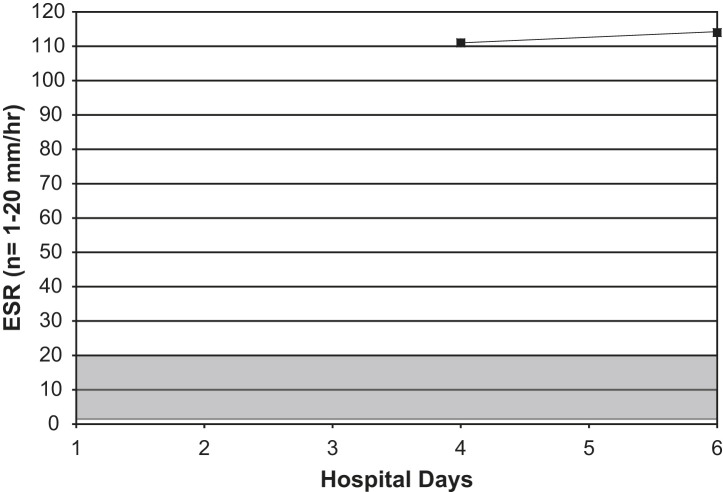

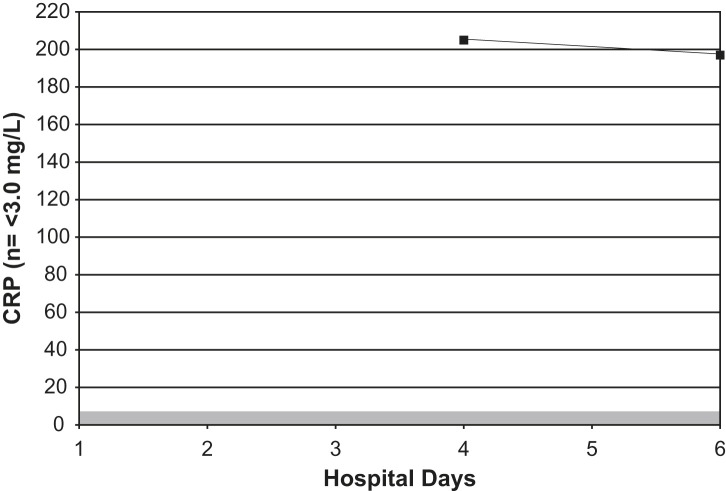

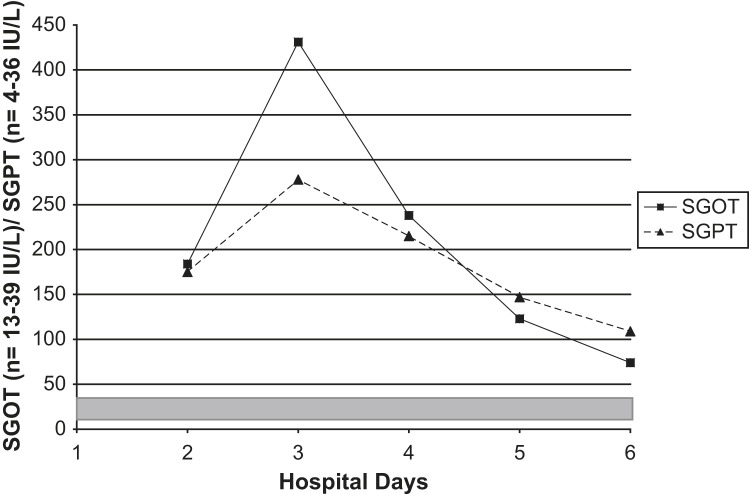

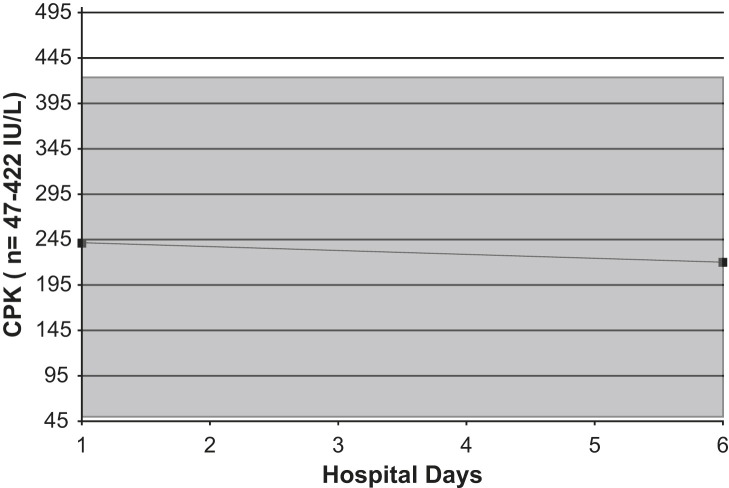

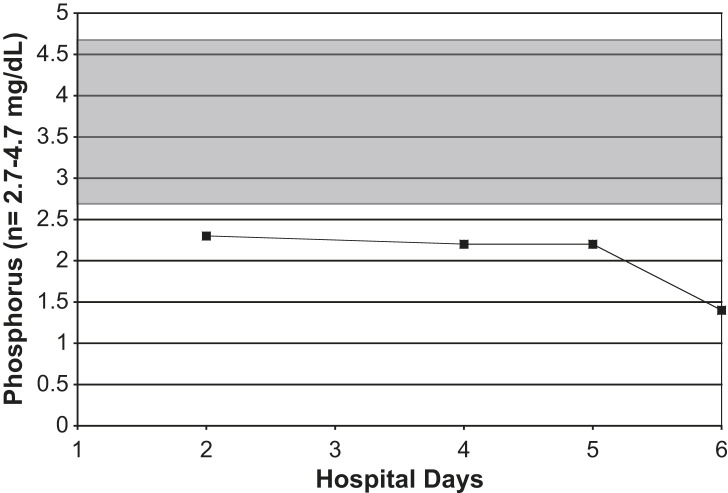

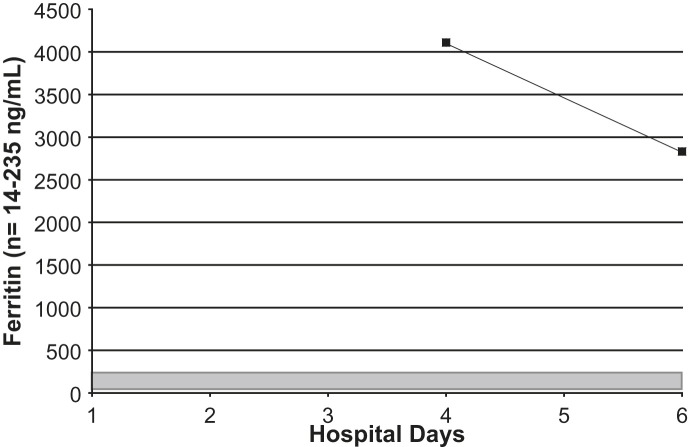

On admission, his white blood cell count was 9.8 K/μL (normal range, 3.9 to 11.0 K/μL), with a differential of 87% neutrophils (normal range, 42% to 75%), 7% stabs (normal range, 0 to 5%), 4% lymphocytes (normal range, 21% to 51%), and 2% monocytes (normal range, 0 to 10%), and with a platelet count of 158 K/μL (normal range, 160 to 392 K/μL). His erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 111 mm/hour (normal range, 1 to 20 mm/hour), and his C-reactive protein level was 205 mg/L (normal range, <3.0 mg/L). His serum sodium level was 132 mEq/L (normal range, 138 to 145 mEq/L), and his serum phosphorus level was 2.3 mg/dL (normal range, 2.7 to 4.7 mg/dL). His serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase (SGPT) level was 175 IU/L (normal range, 4 to 36 IU/L), and his serum transaminase level, ie, serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase (SGOT), was 184 IU/L (normal range, 13 to 39 IU/L). His serum ferritin level was 4110 ng/mL (normal range, 14 to 235 ng/mL), and his creatinine phosophokinase (CPK) level was 241 IU/L (normal range, 47 to 422 IU/L) (Fig 1, Fig 2, Fig 3, Fig 4, Fig 5, Fig 6, Fig 7 ). Admission urinalysis demonstrated 1+ blood and 1 red blood cell. His admission chest x-ray (CXR) revealed right lower-lobe infiltrates/consolidation. Arterial blood gas in room air revealed a pH of 7.49 (normal range, 7.35 to 7.45), a pO2 of 57 mm Hg (normal range, 83 to 108 mm Hg), and an oxygen saturation of 92% (normal range, 95% to 98%). Legionella spp. titers were negative. A clinical syndromic diagnosis of Legionnaires' disease was rendered, using the Winthrop-University Hospital Infectious Disease Division's diagnostic weighted point score system (modified). The patient received treatment with moxifloxacin. Later, during his hospitalization, his urinary Legionella antigen was positive. He was discharged, and recovered at home.

Fig 1.

Serial lymphocyte counts in an adult with Legionnaires' disease. Shaded area = normal range.

Fig 2.

Serial ESRs in an adult with Legionnaires' disease. Shaded area = normal range.

Fig 3.

Serial C-reactive protein measurements in an adult with Legionnaires' disease. Shaded area = normal range.

Fig 4.

Serial serum transaminases SGOTs/SGPTs in an adult with Legionnaires' disease. Shaded area = normal range.

Fig 5.

Serial CPK levels count in an adult with Legionnaires' disease. Shaded area = normal range.

Fig 6.

Serial serum phosphorus levels in an adult with Legionnaires' disease. Shaded area = normal range.

Fig 7.

Serial serum ferritin levels in an adult with Legionnaires' disease. Shaded area = normal range.

Discussion

During epidemics and pandemics, the initial cases are often difficult to recognize. Later, as the pandemic becomes widespread, clinical diagnoses are usually relatively straightforward.4, 11, 12 During the H1N1 pandemic in the New York area in spring and summer 2009, many unexpected diagnostic problems rapidly became apparent. Firstly, the human seasonal influenza season was unusually long, and extended into late spring and early summer. Other respiratory viruses were also circulating in the community at this time when the number of potential H1N1 cases increased. Diagnostic difficulties with testing were problematic. The rapid influenza A screening test (QuickVue A/B, Quidel, San Diego) was used to determine which ED-admitted patients needed influenza precautions and oseltamivir, and these tests were negative in 30% of cases.4, 13, 14 Because positive rapid influenza A testing predicted subsequent RT-PCR positivity for H1N1, no diagnostic or infection-control problems occurred with these patients. Admitted adults with ILIs and negative RIDTs, however, were problematic because most of these patients clinically had H1N1 pneumonia, but these cases could not be confirmed or ruled out by RT-PCR. Because the health department was overwhelmed with requests for RT-PCR, such testing was restricted.4

To help alleviate these problems with laboratory diagnoses, clinical criteria were developed by the Infectious Disease Division at Winthrop-University Hospital for the sake of reliable clinical diagnoses of probable H1N1 pneumonia.15 In our experience, the most important laboratory markers for H1N1 in admitted adults with ILIs and fevers >102°F include otherwise unexplained relative lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, highly elevated CPK, or mildly elevated serum transaminases (SGOT/SGPT).10, 15 Many adult patients admitted via the ED with a diagnosis of influenza or pneumonia had infectious and noninfectious disorders mimicking H1N1 pneumonia. Our clinical criteria permitted a presumptive clinical diagnosis of H1N1 in RIDT-negative hospitalized adults.15

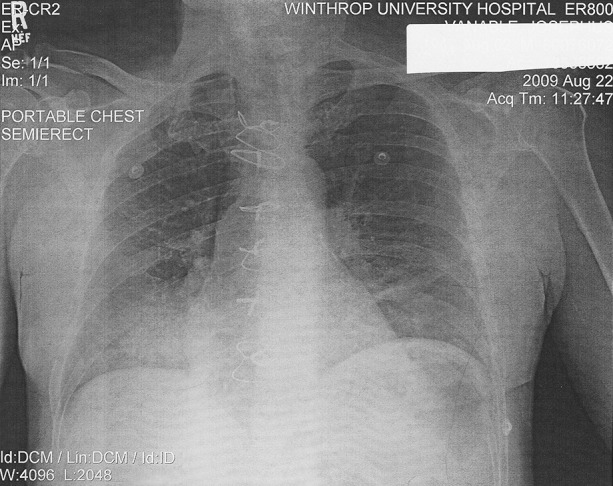

In our case report, the patient presented in the midst of the H1N1 pandemic with fever, shortness of breath, and “pneumonia” to the Winthrop-University Hospital ED. His rapid influenza A test was negative, but other clinical findings were consistent with H1N1 pneumonia, ie, relative lymphopenia and elevated serum transaminases (SGOT/SGPT). 15 He also exhibited several key laboratory test markers of Legionnaires' disease, ie, relative lymphopenia, elevated serum transaminases (SGOT/SGPT), hypophosphatemia, and highly elevated (>2 × n) serum ferritin levels.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 The CXR findings in Legionnaires' disease are legion.21, 22, 23 Although there is no characteristic CXR appearance of Legionnaires' disease, the behavior of the infiltrates is characteristic, ie, they are rapidly progressive and asymmetric.11, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 With H1N1, the initial CXR is clear or shows what appears to be unilateral or bilateral basilar atelectasis. In severe cases, bilateral patchy interstitial infiltrates may be appear on the CXR after 48 to 72 hours of H1N1 pneumonia.4, 24 The Winthrop-University Hospital Infectious Disease Division's diagnostic weighted point score system for Legionnaires' disease (modified) was used to make a clinical syndromic diagnosis in this case25 (Table I ). The differential diagnostic features of H1N1 pneumonia and Legionnaires' disease are listed in Table II .

Table I.

Winthrop-University Hospital Infectious Disease Division's diagnostic weighted point system for diagnosing Legionnaires' disease in adults (modified)

| Presentation | Qualifying conditions† | Point Score |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | ||

| Temperature >102°F∗ | With relative bradycardia | +5 |

| Headache | Acute onset | +2 |

| Mental confusion/lethargy∗ | Not drug-induced | +4 |

| Ear pain | Acute onset | −3 |

| Nonexudative pharyngitis | Acute onset | −3 |

| Hoarseness | Acute, not chronic | −3 |

| Sputum (purulent) | Excluding AECB | −3 |

| Hemoptysis∗ | Mild/moderate | − 3 |

| Chest pain (pleuritic) | −3 | |

| Loose stools/watery diarrhea∗ | Not drug-induced | +3 |

| Abdominal pain∗ | With/without diarrhea | +2 |

| Renal failure∗ | Acute (not chronic) | +3 |

| Shock/hypotension∗ | Excluding cardiac/pulmonary causes | −5 |

| Splenomegaly | Excluding non-CAP causes | −5 |

| Lack of response to B-lactams | After 72 hours (excluding viral pneumonias) | +5 |

| Laboratory tests | ||

| Chest x-ray | Rapidly progressive asymmetric infiltrates∗ (excluding severe influenza [human, avian, swine], HPS, SARS) | +3 |

| Severe hypoxemia with ↑ A-a gradient (>35)∗ | Acute onset | −2 |

| Hyponatremia∗ | Acute onset | +1 |

| Hypophosphatemia | Acute onset | +5 |

| ↑ SGOT/SGPT (early/mild/transient)∗ | Acute onset | +2 |

| ↑ Total bilirubin | Acute onset | +1 |

| ↑ LDH (>400)∗ | Acute onset | −5 |

| ↑ CPK | Acute onset | + 4 |

| ↑ CRP | Acute onset | +5 |

| ↑Cold agglutinin titers (≥1:64) | Acute onset | −5 |

| Relative lymphopenia (<21%)∗ | Acute onset | +5 |

| ↑ Ferritin (>2 × normal)∗ | +5 | |

| Microscopic hematuria∗ | Excluding trauma, BPH, Foley catheter, bladder/renal neoplasms | +2 |

| Likelihood of Legionella | |

| Total point score | > 15 Legionnaires' Disease very likely |

| 5-15 Legionnaires' Disease likely | |

| < 5 Legionnaires' Disease unlikely | |

AECB, Acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis; BPH, Benign prostatic hyperplasia; SARS, Severe acute respiratory syndrome; HPS, Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome; SGOT/SGPT, Serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase/serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase; LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; CPK, Creatine phosphokinase; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Otherwise unexplained (acute and associated with pneumonia).

In adults, otherwise unexplained, acute, and associated with pneumonia.

Adapted from Cunha.25

Table II.

Differential diagnostic features of H1N1 pneumonia and Legionnaires' disease

| Clinical features | Legionnaires' disease | H1N1 pneumonia |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| Fever | + | + |

| Headache | + | + |

| Dry cough | + | + |

| Myalgias | + | + |

| Malaise | + | + |

| Weakness | + | + |

| Dyspnea | + | + |

| Nausea/vomiting | + | + |

| Diarrhea | + | + |

| Chills | + | + |

| Chest pain | ± | ± |

| Sore throat | − | + |

| Mental confusion | ± | − |

| Signs | ||

| Fever >102°F | + | + |

| Relative bradycardia∗ | + | − |

| Tachypnea | + | + |

| Tachycardia | + | + |

| Localized rales | + | − |

| Laboratory abnormalities | ||

| Leukocytosis | + | + |

| Leukopenia | − | ± |

| Relative lymphopenia∗ | ± | + |

| Thrombocytopenia∗ | − | + |

| ↑ SGOT/SGPT∗ | + | + |

| Hyponatremia∗ | + | − |

| Hypophosphatemia∗ | + | − |

| Elevated CPK∗ | + | + |

| Elevated LDH | + | + |

| Elevated procalcatonin levels | + | − |

| Elevated ferritin levels (>2 × normal) | + | − |

| Chest film | ||

| No infiltrates | − | + |

| Lobar consolidation | ± | − |

| Bilateral interstitial patchy infiltrates | ± | ± |

| Diagnosis | ||

|

Legionella urinary antigen Elevated Legionella titers Positive culture on buffered charcoal yeast (BCYE) agar |

RT-PCR for H1N1 |

LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; CPK, Creatine phosphokinase.

Otherwise unexplained.

In this case, the differential diagnosis was more difficult because the presence of relative bradycardia could not be assessed while the patient was in atrial fibrillation. The patient did manifest hypophosphatemia, and had highly elevated ferritin levels that favored a diagnosis of Legionnaires' disease.20, 25 Elevated serum transaminases (SGOT/SGPT) may occur with H1N1 pneumonia and Legionnaires' disease and therefore were diagnostically unhelpful.4, 15

The clue to the diagnosis of this patient was the CXR showing a segmental/lobar left lower-lobe infiltrate (Fig 8 ). This CXR finding, together with key laboratory markers for Legionnaires' disease, prompted specific testing for Legionnaires' disease. His Legionella sp. titers were negative. Later in his admission, his urinary antigen was positive for Legionella pneumophila (serogroups 01-06).26, 27 After initial therapy with azithromycin for Legionnaires' disease, therapy was completed with doxycycline.28, 29, 30 He made a full recovery.

Fig 8.

Admission chest x-ray showing RLL infiltrate due to Legionnaire's Disease during the swine influenza H1N1 pandemic.

The take-home lesson for clinicians from this case is that in the midst of the H1N1 epidemic, other infectious disorders may mimick, eg, Legionnaires' disease. Moreover, because the swine flu H1N1 pandemic occurred in spring and early summer, Legionnaires' disease was not initially suspected, since the peak incidence of Legionnaires' disease usually occurs in late summer and early fall.31, 32, 33

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Update: infections with a swine origin influenza A (H1N1) virus—United States and other countries. April 28, 2009. MMWR. 2009;58:431–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Outbreak of swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus infection—Mexico, March-April 2009. MMWR. 2009;58:467–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunha B.A., Pherez F.M., Strollo S. Swine influenza H1N1: diagnostic dilemmas early in the pandemic. Scand J Infect. 2009;41:900–902. doi: 10.3109/00365540903222465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crosby A.W. Influenza. In: Kiple K.F., editor. The Cambridge world history of human disease. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1993. pp. 807–811. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debré R., Couvreur J. Influenza: clinical features. In: Debré R., Celers J., editors. Clinical virology: the evaluation and management of human viral infections. W.B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1970. pp. 507–515. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson K.G., Webster R.G., Hay A.J., editors. Textbook of influenza. Blackwell Science; Oxford: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayden F.G., Palese P. Influenza virus. In: Richman D.D., Whitley R.J., Hayden F.G., editors. Clinical virology (3rd ed) ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2009. pp. 943–976. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper S.A., Bradley J.S., Englund J.A. Seasonal influenza in adults and children: diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis and institutional outbreak management: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1003–1032. doi: 10.1086/604670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunha B.A. The clinical diagnosis of severe viral influenza A. Infection. 2008;36:92–93. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-7255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunha B.A., Pherez F.M., Schoch P.E. The diagnostic importance of relative lymphopenia as a marker of swine influenza (H1N1) Clin Infect Dis. 2009;47:1454–1456. doi: 10.1086/644496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunha B.A. 3rd ed. Jones & Bartlett; Sudbury, MA: 2010. Pneumonia essentials. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunha B.A. Influenza: historical aspects of epidemics and pandemics. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2004;18:141–156. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(03)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasoo S., Stevens J., Singh K. Rapid antigen tests for diagnosis of pandemic (swine) influenzae A/H1N1. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1090–1093. doi: 10.1086/644743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coker R. Swine flu. Br Med J [Clin Res] 2009;338:1791. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunha B.A., Laguerre M., Syed U. Winthrop-University Hospital Infectious Disease Division's swine influenza (H1N1) pneumonia diagnostic weighted point score system for adults with influenza like illnesses and negative rapid influenza diagnostic tests. Heart Lung. 2009;38:534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunha B.A., Quintiliani R. The atypical pneumonias: a diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Postgrad Med. 1979;66:95–102. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1979.11715248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lattimer G.L., Ormsbee R.A. Marcel Dekker, Inc; New York: 1981. Legionnaires' disease. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaty H.N. State of the art lecture. Clinical features of legionellosis. In: Thornsberry C., Balows A., Feeley J.C., editors. Legionella: proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 1984. pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunha B.A. Clinical diagnosis of Legionnaires' disease. Semin Respir Infect. 1998;13:116–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strampfer M.J., Cunha B.A. Legionnaire's disease. Semin Respir Infect. 1987;2:228–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coletta F.S., Fein A.M. Radiological manifestation of Legionella/ Legionella-like organisms. Semin Respir Infect. 1998;13:109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunha B.A., Ortega A.M. Atypical pneumonia. Extrapulmonary clues guide the way to diagnosis. Postgrad Med. 1996;99:123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunha B.A. The extrapulmonary manifestations of community-acquired pneumonias. Chest. 1998;112:945. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.3.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunha B.A. Empiric antimicrobial therapy of community acquired pneumonia: clinical diagnosis versus. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009;13:1–3. doi: 10.1080/00365540903147035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunha B.A. Severe Legionella pneumonia: rapid diagnosis with Winthrop-University Hospital's weighted point score system (modified) Heart Lung. 2008;37:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marlow E., Whelan C. Legionella pneumonia and use of the Legionella urinary antigen test. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:E1–E2. doi: 10.1002/jhm.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen C.W., Elverdal P., Jørgensen C.S. Comparison of the sensitivity of the Legionella urinary antigen EIA kits from Binax and Biotest with urine from patients with infections caused by less common serogroups and subgroups of Legionella. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;287:817–820. doi: 10.1007/s10096-008-0697-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunha B.A. Empiric antibiotic therapy for community-acquired pneumonia: guidelines for the perplexed? Chest. 2004;125:1913–1921. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.5.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunha B.A. Fluoroquinolones in the treatment of Legionnaires' disease. Penetration. 2000;3:32–39. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunha B.A. Doxycycline for community acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:870. doi: 10.1086/377615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunha B.A. Swine influenza (H1N1) pneumonia: Clinical considerations. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24:203–228. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunha B.A. Legionnaire's Disease: Clinical differentiation from typical and other atypical pneumonias. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24:73–105. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cunha B.A., Mickail N., Thekkel V. Unexplained increased incidence of Legionnaire's Disease during the “Herald Wave” of the H1N1 influenza pandemic. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:562–563. doi: 10.1086/652453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]