Abstract

Since no randomized controlled trials have been conducted on the treatment of viral pneumonia by antivirals or immunomodulators in immunocompetent adults, a review of such anecdotal experience are needed for the more rational use of such agents. Case reports (single or case series) with details on their treatment and outcome in the English literature can be reviewed for pneumonia caused by human or avian influenza A virus (50 patients), varicella zoster virus (120), adenovirus (29), hantavirus (100) and SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) (841). Even with steroid therapy alone, the mortality rate appeared to be lower when compared with conservative treatment for pneumonia caused by human influenza virus (12.5% vs. 42.1%) and hantavirus (13.3% vs. 63.4%). Combination of an effective antiviral, acyclovir, with steroid in the treatment of varicella zoster virus may be associated with a lower mortality than acyclovir alone (0% vs. 10.3%). Combination of interferon alfacon-1 plus steroid, or lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin plus steroid were associated with a better outcome than ribavirin plus steroid (0% vs. 2.3% vs. 7.7%, respectively). Combination of lopinavir/ritonavir plus ribavirin significantly reduced the virus load of SARS-CoV in nasopharyngeal, serum, stool and urine specimens taken between day 10 and 15 after symptom onset when compared with the historical control group treated with ribavirin. It appears that the combination of an effective antiviral and steroid was associated with a better outcome. Randomized therapeutic trial should be conducted to ascertain the relative usefulness of antiviral alone or in combination with steroid.

Keywords: Viral pneumonia, Treatment, SARS, Immunocompetent host

1. Introduction

The start of the new millennium is marked by two emerging infectious diseases coming from wild game food animals and poultry.1, 2 Both SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and avian influenza A H5N1 virus predominantly manifest as acute community acquired pneumonia with no response to empirical treatment by antibacterials covering typical and atypical agents.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 SARS-CoV and avian influenza A H5N1 pneumonia are associated with significant mortality.7, 8, 9 Unfortunately, few prospective studies have been performed with documentation of the virus load changes during the course of illness for any respiratory viral pneumonia.8, 10 The literature on the histological changes or pathogenesis of this condition is scarce. No randomized placebo-controlled treatment trial has ever been conducted. Such lack of data was often attributed to the lack of rapid diagnostic tests and effective antivirals. During the SARS outbreak, the empirical use of ribavirin and steroids were regarded as controversial.11, 12, 13, 14 Due to the explosive nature of the outbreak, randomized controlled trials on treatment could not be organized. Therefore, we attempt to review the literature on the rationale and strategy used in the treatment of acute community acquired viral pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. Virus load data and serological changes of acute respiratory viral pneumonia available in the literature, as well as from our SARS patients were included in this analysis.

2. Materials and methods

All the case reports and series with clinical details involving medical therapy of viral pneumonia including SARS in patients aged 15 years or above were included in this review. Patients with immunosuppressive conditions such as congenital or acquired immunodeficiencies, solid or marrow transplants, undergoing chemotherapy, and pregnancy were excluded. Where appropriate, the cited bibliographies were also retrieved for analysis.

Preliminary review of these publications suggested that viral pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV constituted the majority of cases reported in the literature. However, similar to other causes of viral pneumonia, little information on the virus load changes with respect to treatment was systematically reported. Therefore, laboratory data from our cohort of 152 SARS patients who fulfilled the modified WHO definition were retrieved.5 Virus load was measured on nasopharyngeal, serum, stool and urine specimens taken between day 10 and 15 after symptom onset. Part of these data was previously reported.8, 10, 15, 16 The virus load results were correlated with the specific antiviral regimens, namely ribavirin with and without lopinavir/ritonavir for SARS. Serial quantitative RT-PCRs and IgG titers of SARS-CoV were performed in 12 randomly selected patients who were treated with ribavirin and corticosteroid on day 5, 10, 15 and 20 after onset of symptoms. To compare the serial virus load and antibody seroconversion with other respiratory virus infections, the English-language literature was searched to identify studies with detailed description of serial virus load and antibody titers during the course of infection.

3. Results

In the literature review, there were 1997 and 322 English publications on human studies identified in PubMed when the combination of keywords ‘virus, pneumonia, treatment’ and ‘SARS, treatment’ were used on 11 January 2004, respectively. Among the 1997 publications, those related to HIV and AIDS patients (950), cancer and transplant patients (501), and vaccine and immunization topics (287), were excluded. The remaining 259 papers were retrieved and analysed. All the 322 SARS paper were retrieved and analysed. Subsequent PubMed search using the keywords of ‘influenza, pneumonia, treatment’, ‘respiratory syncytial virus, pneumonia, treatment’, ‘varicella, pneumonia, treatment’, ‘adenovirus, pneumonia, treatment’, and ‘hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, treatment’ identified another 623, 267, 240, 146 and 83 papers, respectively. The cited bibliographies, if relevant, were also included in this review. However, only 62 of these 1940 papers contained clinical details and information on the medical treatment of viral pneumonia (44 papers) and SARS (18 papers), respectively.

Of the 302 patients with non-SARS viral pneumonia in 44 case reports or series (Table 1 ), their aetiological diagnoses of human influenza A virus (n=38), avian influenza A H5N1 virus (n=12), varicella zoster virus (VZV) (n=120), adenovirus (n=29), hantavirus (n=100), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (n=1), measles virus (n=1), and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) (n=1), were documented by a combination of clinical features, radiographic changes, virological and serological tests.6, 7, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58 Demographic details were mentioned in 171 (56.6%) patients. There were 113 males and 58 females, with a median age of 31 years (ranged 15–88). The small number of patients suffering from pneumonia caused by RSV, measles, EBV precluded any meaningful analysis or discussion.56, 57, 58 As for the other agents, the overall mortality ranges from 9.2% (VZV), 20.7% (adenovirus), 31.6% (human influenza A virus), 49% (hantavirus) to 66.7% (avian influenza A H5N1 virus).

Table 1.

Summary of literature reported cases in the medical management of viral pneumonia other than SARS in immunocompetent host

| Antiviral therapies and/or immunomodulating agents with respect to different viral pathogens; sex & age (if mentioned) | Number of cases | Mechanical ventilation (%) | Mortality (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human influenza A pneumonia—8 M/8 F; median age 65 years (23–80 years) | 38 | 24 (63.2) | 12 (31.6%) | 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 |

| Conservative treatment | 19 | 12 (63.2%) | 8 (42.1%) | 17–20 |

| Antiviral alone: Rimantadine (1), oseltamivir (5), combination of oseltamivir and rimantadine (5) | 11 | 8 (72.7%) | 3 (27.3%) | 20, 22, 23 |

| Corticosteroid alone: MP 500 mg IVI q6 h (1); hydrocortisone 250 mg IVI q4 h and tailing from day 6 to day 26 after admission (1) | 8 | 4 (50%) | 1 (12.5%) | 20, 21, 22 |

| Avian influenza A H5N1 pneumonia—6 M/6 F; median age of 24.5 years (16–60 years) | 12 | 6 (50%) | 8 (66.7%) | 6, 7, 24, 25 |

| Conservative treatment | 2 | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 24 |

| Antiviral alone: Amantadine (4), oseltamivir (3) | 7 | 3 (42.9%) | 5 (71.4%) | 6, 24, 25 |

| Antiviral and immunomodulators: Amantadine for 3 days and steroid in 1; oseltamivir for 5 days and MP 1–2 mg/kg IVI q6 h for 3 and 4 days in 2 patients, respectively | 3 | 3 (100%) | 2 (66.7%) | 6, 7 |

| VZV pneumonia—61 M/28 F; median age of 31 years (22–88 years) | 120 | 37 (30.8%) | 11 (9.2%) | 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 |

| Conservative treatment | 33 | 2 (6.1%) | 4 (12.1%) | 26, 27, 28, 29 |

| Antiviral alone: Intravenous acyclovir (66), vidarabine (2) | 68 | 26 (38.2%) | 7 (10.3%) | 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 |

| Antiviral and immunomodulators: intravenous acyclovir and corticosteroid (17), intravenous acyclovir and IVIG (2) (hydrocortisone 200 mg IVI q6 h for 2 days in 6; hydrocortisone 100 mg IVI q6 h and tailing over 1 month in 1; P 60 mg po qd and tailing over 32 weeks in 1; MP 60 mg IVI q6 h for 2 days in 1 patient) | 19 | 9 (47.4%) | 0 (0%) | 28, 29, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 |

| Adenoviral pneumonia—7 M/3 F; median age of 22 years (18–48 years) | 29 | 12 (41.4%) | 6 (20.7%) | 21, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 |

| Conservative treatment | 25 | 10 (34.5%) | 4 (16%) | 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 |

| Corticosteroid alone | 4 | 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | 21, 44, 49, 50 |

| Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome—30 M/11 F; median age of 33 years (15–63 years) | 100 | 25/56 (44.6%) | 49 (49%) | 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 |

| Conservative treatment | 41 | 18/26 (69.2%) | 26 (63.4%) | 51, 52, 53 |

| Antiviral alone: intravenous ribavirin | 44 | NM | 21 (47.7%) | 51, 54, 55a |

| Corticosteroid alone | 15 | 7 (46.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | 52, 53 |

| RSV pneumonia—F/64; aerosolized ribavirin 6 gm 22 hours daily for 5 days | 1 | 1 (100%) | 0 | 56 |

| Measles pneumonia—F/29; MP 1 gm IVI daily for 2 days and tailing dose thereafter; vitamin A 200 000 U orally for 2 days | 1 | 1 (100%) | 0 | 57 |

| EBV pneumonia—M/30; P 100 mg po daily for 11 days then tailing gradually | 1 | 1 (100%) | 0 | 58 |

In the treatment of human influenza A infection, antiviral agents such as rimantadine (one patient), oseltamivir (five patients), and a combination of rimantadine and oseltamivir had been used at a median of 3 days (ranged 1–7 days) after admission.20, 21, 22, 23 High dose corticosteroid without antiviral therapy was also attempted.20, 21, 22 The dose of steroids ranged from hydrocortisone 250 mg IVI every 4 hourly to methylprednisolone 500 mg IVI every 6 hourly.21, 22 Amantadine (four patients), oseltamivir (three patients), and a combination of antivirals and corticosteroid (three patients) had also been used in the treatment of avian influenza A H5N1 infection.6, 7 There was no apparent benefit since the antiviral agents were started at a median of 5 days (ranged 0–5 days) after admission. Corticosteroid such as intravenous methylprednisolone 1–2 mg/kg every 6 hourly for 3–4 days had been given in three mechanically ventilated patients but two of them died of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).6, 7

As for VZV pneumonia, antiviral therapy including intravenous acyclovir 10–15 mg/kg every 8 hourly for 7–10 days was initiated in 66 out of 120 patients.26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 Two patients were treated with vidarabine before the widespread use of acyclovir.27, 38 Corticosteroids were combined with acyclovir in 17 patients.28, 29, 39, 40, 41 The dosage and duration of steroids were quite variable (Table 1).29, 39, 40, 41 Two patients received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) together with intravenous acyclovir had a favorable outcome.42, 43 The mortality of patients who received acyclovir or vidarabine alone was seven out of 68 (10.3%), whereas four patients managed with supportive care died. Only one out of 25 patients died if intravenous acyclovir was initiated within 4 days of admission.27, 34, 35 There was no death in patients treated with a combination of acyclovir and immunomodulators such as corticosteroid and IVIG.28, 29, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43

As for adenoviral pneumonia, no antiviral was ever used for their treatment. Two of four (50%) patient receiving steroid died, which appeared to be higher than patients managed conservatively.21, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 The mortality for hantavirus pulmonary syndrome treated with intravenous ribavirin (47.7%) appeared to be only slightly lower than those treated conservatively (63.4%).51, 52, 53, 54, 55 The use of methylprednisolone was associated with a dramatic decrease of mortality to 13.3%.52, 53

Though there were 849 cases of SARS with treatment details reported in the literature, many of these patients were diagnosed according to the clinical criteria issued by WHO with or without laboratory confirmation (Table 2 ).3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71 One of the case series was not included because patients treated by different treatment regimens were aggregated together and could not be analysed.72 There were 349 males and 500 females. Except for 13 (1.5%) patients who were treated conservatively, antiviral therapy and/or immunomodulating therapy were given in all other patients. Of 772 patients receiving specific antiviral therapy and/or immunomodulating therapy, 675 (87.4%) were treated with ribavirin containing regimens and 44 (5.7%) were treated with lopinavir/ritonavir containing regimens during the initial phase of the disease. Immunomodulating therapy without antiviral agents was initiated in 53 of 772 (6.9%) patients. Recombinant interferon alpha, corticosteroid, and a combination of interferon alfacon-1 and corticosteroid were used in 30 (3.9%), 14 (1.8%) and 9 (1.2%) cases, respectively. Of the 64 patients receiving treatment during clinical deterioration, ribavirin or oseltamivir, lopinavir/ritonavir, and convalescent plasma were given as rescue medical therapy in 32 (50%), 31 (48.4%) and 1 (1.6%), respectively. High dose pulse methylprednisolone was used during clinical deterioration such as oxygen desaturation, worsening of radiographic infiltrates in the chest, recurrent fever without evidence of nosocomial sepsis in some reports. However, the number of patients requiring pulse steroids was not mentioned in most of them.5, 8, 10, 59, 60, 61, 62 Furthermore, IVIG, thymic peptides, and recombinant human thymus proteins were used in some patients but the clinical details were not sufficient for any meaningful analysis.61 The overall mortality was 7.7% in these 849 SARS cases. No obvious difference was noted irrespective of whether the patients were treated by ribavirin with or without corticosteroids, corticosteroids alone, or recombinant interferon-alpha given on admission or during deterioration. However, the mortality is only 2.3% in a group of 44 patients treated by lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin and corticosteroids,64 and 0% for nine patients treated with interferon alfacon-1 and corticosteroids.65 Only one patient received convalescent plasma as rescue therapy.67

Table 2.

Summary of literature reported cases in the medical management of SARS in adult

| Antiviral therapies and/or immunomodulating agents, in addition to empirical broad spectrum antibiotics therapy | Number of cases | Sex (M:F) | Non-invasive ventilation (%) | Mechanical ventilation (%) | Pulse MP for clinical deterioration (%) | Mortality (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative supportive treatment | 13 | 7:6 | 0 | 4 (30.8%) | 0 | 2 (15.4%) | 3, 5, 59, 60, 68, 69, 70, 71 |

| Initial medical management (n=772) | |||||||

| Ribavirin with or without oseltamivir | 47 | 19:28 | 10 (21.3%) | 6 (12.8%) | 0 | 3 (6.4%) | 3 |

| Ribavirin and corticosteroid | 611 | 263:348 | 4 (0.7%) | 104 (17%) | 54/95 (56.8%) | 47 (7.7%) | 4, 5, 8, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 |

| Ribavirin and high dose pulse MP | 17 | 7:10 | 0 | 1 (5.9%) | 4 (23.5%) | 1 (5.9%) | 63 |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir, ribavirin and corticosteroid | 44 | 12:32 | 0 | 0 | 12 (27.3%) | 1 (2.3%) | 10a,64 |

| Corticosteroid | 14 | 3:11 | 0 | 3 (21.4%) | 2 (14.3%) | 1 (7.1%) | 65, 68 |

| Interferon alfacon-1 and corticosteroid | 9 | 3:6 | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 5 (55.6%) | 0 | 65 |

| Recombinant interferon alpha | 30 | 11:19 | 8 (26.7%) | 2 (6.7%) | 0 | 2 (6.7%) | 61 |

| Rescue medical treatment (n=64) | |||||||

| Ribavirin or oseltamivir | 20 | 5:15 | 0 | 6 (30%) | 0 | 3 (15%) | 66 |

| Ribavirin and corticosteroid | 12 | 6:6 | 0 | 12 (100%) | NM | 1 (8.3%) | 5 |

| Convalescent plasma | 1 | F | 0 | 0 | 1 (100%) | 0 | 67 |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 31 | 13:18 | 0 | 3 (9.7%) | 31 (100%) | 4 (12.9%) | 64 |

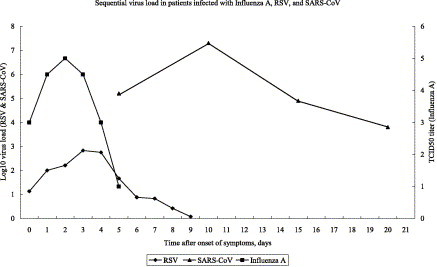

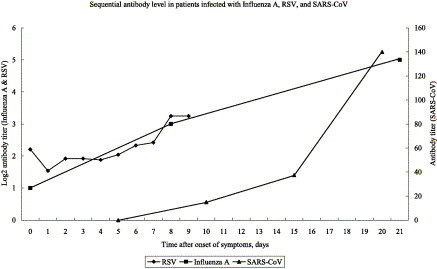

Of the 152 SARS patients in our cohort, their clinical presentation, virological test results, and treatment regimens have been previously reported.8, 10, 16 The virus load of their nasopharyngeal, serum, stool, and urine specimens collected between day 10 and 15 after onset of symptoms are tabulated in Table 3 . There was no significant relationship between virus load, age, and the presence of co-morbidities. However, significant decreases in virus load were observed when lopinavir/ritonavir was added to ribavirin (Table 3). It is also interesting to note that stool virus load is significantly higher in males (7.0 vs. 5.5 log10 copies/ml, P=0.02), whereas that of the urine is significantly higher in females (1.6 vs. 0.6 log10 copies/ml, P=0.01). Of the 111 (73%) historical controls treated with ribavirin and corticosteroids, 12 randomly selected patients had serial virus load studies performed on their nasopharyngeal specimens; their mean virus loads were 5.2, 7.3, 4.9 and 3.8 log10 copies/ml at day 5, 10, 15 and 20 after onset of symptoms, respectively (Fig. 1 ). The decline in virus load in nasopharyngeal specimens coincided with the appearance of IgG antibody titers against SARS-CoV during the course of infection (Fig. 2 ). Since similar clinical studies of other respiratory viral pneumonias were not available in the literature except for a naturally occurring case of influenza,73 another 12 cases of experimental infection with RSV by artificial inoculation into healthy volunteers were adopted for comparison (Fig. 2).74 The virus load of influenza A virus and RSV peaked at day 2 and 3, respectively, whereas that of SARS-CoV occurred at day 10 after onset of symptoms (Fig. 1). As for the antibody response, baseline antibodies of influenza A virus and RSV were detectable in serum and nasal washings but antibodies against SARS-CoV were not present until day 10 after symptom onset.

Table 3.

Correlation of demographic data, treatment intervention, and quantitative RT-PCR of clinical specimens between day 10 and 15 in 152 patients with SARS

| Demographic data and treatment intervention | Mean (SD) virus load (log10 copies/ml) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal specimens (n=152) | Serum (n=53) | Stool (n=94) | Urine (n=111) | |

| Age | ||||

| Age equal or more than 60 years (n=20) | 2.5 (3.0) | 1.2 (1.3) | 6.7 (3.4) | 1.4 (2.3) |

| Age less than 60 years (n=132) | 2.3 (3.1) | 1.1 (1.5) | 6.0 (3.0) | 1.3 (2.1) |

| P value | 0.83 | 0.96 | 0.46 | 0.84 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (n=58) | 2.9 (3.3) | 1.4 (1.4) | 7.0 (2.6) | 0.6 (1.6) |

| Female (n=94) | 2.0 (2.9) | 1.0 (1.4) | 5.5 (3.2) | 1.6 (2.3) |

| P value | 0.11 | 0.44 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Co-morbidity | ||||

| Presence of co-morbidity (n=28) | 2.9 (3.3) | 1.1 (1.7) | 5.9 (3.4) | 1.2 (2.1) |

| Absence of co-morbidity (n=124) | 2.2 (3.0) | 1.1 (1.4) | 6.1 (3.0) | 1.3 (2.1) |

| P value | 0.31 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.79 |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir therapy in addition to ribavirin | ||||

| Presence of lopinavir/ritonavir therapy (n=41) | 1.3 (2.6) | 0.4 (0.9) | 4.3 (3.3) | 0.5 (1.4) |

| Absence of lopinavir/ritonavir therapy (n=111) | 2.8 (3.1) | 1.4 (1.5) | 6.9 (2.6) | 1.7 (2.3) |

| P value | <0.01 | 0.04 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

Figure 1.

Sequential quantitative measurements of viral shedding from upper respiratory tract during infections with influenza A virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV). Influenza A virus quantitation was performed on throat washings from a naturally occurring case of influenza in a 28-year-old male. Influenza A/Victoria H3N2 virus was isolated using cell cultures.73 RSV quantitation was done on nasal washings from 12 subjects inoculated nasally with 104.7 TCID50 (50 median tissue culture infectious dose) RSV A2 challenge pool of virus, developed by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. RSV virus load was measured by quantitative RT-PCR using primers based on the nucleotide sequences from the F gene of RSV group A and B viruses.74 SARS-CoV quantitation was performed on nasopharyngeal specimens from infected patients. SARS-CoV virus load of 12 patients are measured by quantitative RT-PCR of Pol gene from nasopharyngeal specimens.

Figure 2.

Changing titers of serum antibody of influenza A virus, nasal IgA of RSV, and IgG of SARS-CoV after onset of symptoms. Serum antibody titer (HAI) of influenza A virus was determined using serial sera from a patient who was naturally infected with influenza A virus (same patient as shown in Fig. 1). Mean RSV nasal IgA titers were obtained from nasal washings of 12 subjects who were inoculated with RSV (same group of patients as shown in Fig. 1). Mean IgG titers of SARS-CoV were obtained using sera from 12 patients who were infected with SARS-CoV (same group of patients as shown in Fig. 1).

4. Discussion

Despite exhaustive laboratory investigations, an aetiological agent could be identified in only around half of the patients suffering from acute community acquired pneumonia.75 In immunocompetent adults with community acquired pneumonia, pyogenic bacteria still constitute the majority of microbiologically documented agents in prospective studies.76, 77 The lack of readily available rapid diagnostic tests for respiratory viral infections is one of the major reasons for the lack of reports on the natural history, pathogenesis, and treatment of viral pneumonia. Well-documented treatment regimens by randomized control trials are only available for HIV, HCV, HBV, HSV, VZV, CMV and human influenza without pneumonia.78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93 Moreover, in vitro susceptibility of viruses may not correlate with clinical efficacy, as in the case of interferon-alpha used for the treatment of genital herpes.94 No improvement in symptoms score or duration of genital lesions was found irrespective of whether systemic or topical interferon-alpha was used.95 In the case of acute RSV bronchiolitis, the efficacy of aerosolized ribavirin was also questionable.96, 97

Due to the lack of effective antiviral therapy for viral pneumonia, alternative strategies using immunomodulation were proposed as early as the 1970s.21 This was not unexpected, since the cytotoxic T cell response may lead to immunopathological damage after an initial period of host damage mediated by virus induced cytolysis. The present literature review suggests that at least in the case of human influenza A virus and hantavirus pneumonia, steroid therapy alone may improve the outcome.20, 21, 22, 52, 53 In the case of VZV pneumonia, the absence of mortality in cases treated with the addition of steroid to an efficacious antiviral agent such as acyclovir seems to support such an approach.28, 29, 39, 40, 41 Despite some decrease in mortality in patients (47.7% vs. 63.4%), ribavirin is not considered as an effective antiviral for hantavirus.51, 52, 53, 54, 55 However, the use of steroids during the phase of severe ARDS of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome may be associated with reduction in mortality (13.3% vs. 63.4%).52, 53 As emphasized by a group reporting on a cluster of adenoviral pneumonia, the use of high dose steroids without an effective antiviral may actually increase mortality.47 However the number of adenoviral pneumonia treated by steroids is too small to justify such a conclusion. Overall, the dosage and duration of steroid therapy for viral pneumonia were extremely heterogenous, future randomized clinical studies should be conducted to ascertain the dosage and duration of steroids associated with the least complication which includes secondary infection and avascular necrosis of bone.

Another difficulty in the management of viral pneumonia is the early peaking of the virus load which leaves a narrow window of opportunity for antiviral treatment.73, 74 In both human influenza A and RSV, the virus loads peaked at around 2–3 days after symptom onset in natural and experimental infections of healthy adults (Fig. 1).73, 74 The early control of virus load in these two infections may be explained by the brisk antibody response, possibly due to previous antigenic exposure (Fig. 2).73, 74 A completely different picture emerges in the case of SARS. The virus load in SARS patients peaked at around day 10 with a very large area under the curve when compared with those of human influenza A virus and RSV (Fig. 1). The onset of antibody response was also delayed and started to appear at around day 10. The failure of innate immunity and the relatively delayed onset of adaptive antibody response to control virus replication may be the explanations for the high mortality of this infection. Our previous studies showed that mortality is directly related to the virus load in nasopharyngeal specimens on admission and at day 10.16, 98 The mortality was also correlated with the number of RT-PCR positive specimens from different body sites including nasopharyngeal, serum, stool, or urine.98 Therefore, an effective antiviral which could reduce the peak virus load and area under the curve is the key to the successful treatment of SARS and perhaps avian influenza A H5N1 virus, since the general population has no immunological memory towards these two viruses.

Intravenous ribavirin was empirically used as a broad-spectrum antiviral agent at the beginning of the SARS epidemic in many countries.3, 4, 5, 8, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 66 Ribavirin was selected as it has broad-spectrum antiviral activities possibly through the interference of cellular inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase.99 It has been shown to be effective against mouse coronavirus in the setting of fulminant murine hepatitis.100 Although the in vitro antiviral activity of ribavirin is weak, it has an indirect immunomodulatory activity by decreasing the release of proinflammatory cytokines from macrophages of mice. It may also switch the immune response of mice from a T-helper-2 to a T-helper-1 response,100 which is beneficial for most intracellular infection. Subsequently in vitro susceptibility testing suggests that antiviral effect could only be achieved at a very high concentration which is difficult to achieve clinically,101 despite the fact that ribavirin is known to be concentrated in some cell lines such as African green monkey kidney (Vero 76) and mouse 3T3 cells.102 Moreover, the use of high dose regimens indicated for the treatment of haemorrhagic fever was associated with significant hemolysis.12, 72 Thus other options were diligently searched during the epidemic. Lopinavir/ritonavir was then used in addition to ribavirin because of a weak in vitro antiviral activity on the prototype SARS-CoV.10 The checkerboard assay demonstrated synergisim between lopinavir and ribavirin at a low viral inoculum.10 Other reports suggested that glycyrrhizin, interferon beta (Betaferon), interferon alpha n−1 (Wellferon), interferon alpha n−3 (Alferon), leucocytic interferon alpha, and baicalin may also have in vitro activity.101, 103, 104, 105 However, interferons were not considered by most clinicians during the epidemic because of their known proinflammatory activity, which may potentiate the inflammatory damage initiated by the viral infection, and the reported side effects of interstitial pneumonitis and bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia.106 Subsequently pegylated recombinant interferon alpha 2b was shown to be effective as pre-exposure and perhaps very early postexposure prophylaxis in cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis) experimentally infected with SARS-CoV.107 Though different preparations of interferons appeared to be effective in vitro, only recombinant interferon alpha and interferon alfacon-1 has been used in SARS patients.61, 65 Moreover it is still early to suggest which interferon is likely to be effective in human trial because contradictory reports on the in vitro susceptibility tests were reported for interferon beta 1a101, 108 and interferon alpha 2b.101, 109

This review has summarized the anecdotal reports on the treatment of viral pneumonia. The findings may be biased since positive results are more likely to be reported. Steroids appeared to confer some benefit in patients with ARDS due to hantavirus, human influenza virus and VZV. However, the early use of high dose steroids may be counterproductive in the absence of an effective antiviral agent. Randomized placebo controlled trials utilizing different regimens of antivirals with or without steroids should be considered for the treatment of SARS and other viral pneumonias in the future.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge research funding from the Vice-Chancellor SARS Research Fund, Suen Chi Sun Charitable Foundation SARS Research Fund, The University of Hong Kong. We are most grateful to Dr Rodney Lee for critical review of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Guan Y., Zheng B.J., He Y.Q. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003;302:276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webster R.G. Wet markets—a continuing source of severe acute respiratory syndrome and influenza? Lancet. 2004;363:234–236. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15329-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poutanen S.M., Low D.E., Henry B. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsang K.W., Ho P.L., Ooi G.C. A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1977–1985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuen K.Y., Chan P.K., Peiris M. Clinical features and rapid viral diagnosis of human disease associated with avian influenza A H5N1 virus. Lancet. 1998;351:467–471. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)01182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran T.H., Nguyen T.L., Nguyen T.D. Avian influenza A (H5N1) in 10 patients in Vietnam. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1179–1188. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peiris J.S., Chu C.M., Cheng V.C. Clinical progression and virus load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361:1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Summary table of SARS cases by country, 1 November 2002–7 August 2003. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/en/country2003_08_15.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2004.

- 10.Chu C.M., Cheng V.C., Hung I.F. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax. 2004;59:252–256. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cyranoski D. Critics slam treatment for SARS as ineffective and perhaps dangerous. Nature. 2003;423:4. doi: 10.1038/423004a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knowles S.R., Phillips E.J., Dresser L., Matukas L. Common adverse events associated with the use of ribavirin for severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1139–1142. doi: 10.1086/378304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oba Y. The use of corticosteroids in SARS. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2034–2035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200305153482017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernard G.R. Corticosteroids: the ‘terminator’ of all untreatable serious pulmonary illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1409–1410. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2310004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan K.H., Poon L.L., Cheng V.C. Detection of SARS coronavirus in patients with suspected SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:294–299. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng V.C., Hung I.F., Tang B.S. Viral replication in the nasopharynx is associated with diarrhea in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:467–475. doi: 10.1086/382681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor G.J., Brenner W., Summer W.R. Severe viral pneumonia in young adults. Chest. 1976;69:722–728. doi: 10.1378/chest.69.6.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winterbauer R.H., Ludwig W.R., Hammar S.P. Clinical course, management, and long-term sequelae of respiratory failure due to influenza viral pneumonia. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1977;141:148–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliveira E.C., Marik P.E., Colice G. Influenza pneumonia: a descriptive study. Chest. 2001;119:1717–1723. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.6.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawayama T., Fujiki R., Rikimaru T., Oizumi K. Clinical study of severe influenza virus pneumonia that caused acute respiratory failure. Kurume Med J. 2001;48:273–279. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.48.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferstenfeld J.E., Schlueter D.P., Rytel M.W., Molloy R.P. Recognition and treatment of adult respiratory distress syndrome secondary to viral interstitial pneumonia. Am J Med. 1975;58:709–718. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(75)90508-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greaves I.A., Colebatch H.J., Torda T.A. A possible role for corticosteroids in the treatment of influenzal pneumonia. Aust N Z J Med. 1981;11:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doi M., Takao S., Kaneko K. Two cases of severe bronchopneumonia due to influenza A (H3N2) virus: detection of influenza virus gene using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Intern Med. 2001;40:61–67. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.40.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan P.K. Outbreak of avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in Hong Kong in 1997. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(Suppl 2):S58–S64. doi: 10.1086/338820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peiris J.S., Yu W.C., Leung C.W. Re-emergence of fatal human influenza A subtype H5N1 disease. Lancet. 2004;363:617–619. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15595-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hockberger R.S., Rothstein R.J. Varicella pneumonia in adults: a spectrum of disease. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:931–934. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davidson R.N., Lynn W., Savage P., Wansbrough-Jones M.H. Chickenpox pneumonia: experience with antiviral treatment. Thorax. 1988;43:627–630. doi: 10.1136/thx.43.8.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nilsson A., Ortqvist A. Severe varicella pneumonia in adults in Stockholm County 1980–1989. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28:121–123. doi: 10.3109/00365549609049061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mer M., Richards G.A. Corticosteroids in life-threatening varicella pneumonia. Chest. 1998;114:426–431. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laufenburg H.F. Varicella pneumonia: a case report and review. Am Fam Physician. 1994;50:793–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oh H.M., Chew S.K. Varicella pneumonia in adults—clinical spectrum. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1996;25:816–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeVaul K.A., Garner C.E. Varicella-zoster virus pneumonia in the adult patient. J Emerg Nurs. 1997;23:102–104. doi: 10.1016/s0099-1767(97)90093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Potgieter P.D., Hammond J.M. Intensive care management of varicella pneumonia. Respir Med. 1997;91:207–212. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(97)90040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlossberg D., Littman M. Varicella pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1630–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Daher N., Magnussen R., Betts R.F. Varicella pneumonitis: clinical presentation and experience with acyclovir treatment in immunocompetent adults. Int J Infect Dis. 1998;2:147–151. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(98)90117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chou D.W., Lee C.H., Chen C.W., Chang H.Y., Hsiue T.R. Varicella pneumonia complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome in an adult. J Formos Med Assoc. 1999;98:778–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nee P.A., Edrich P.J. Chickenpox pneumonia: case report and literature review. J Accid Emerg Med. 1999;16:147–150. doi: 10.1136/emj.16.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hepburn N.C., Carley R.H. Adult respiratory distress syndrome secondary to varicella infection in a young adult. J R Army Med Corps. 1989;135:81–83. doi: 10.1136/jramc-135-02-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lau L.G. Adult varicella pneumonia that responded to combined acyclovir and steroid therapy. Med J Malaysia. 1999;54:270–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keane J., Gochuico B., Kasznica J.M., Kornfeld H. Usual interstitial pneumonitis responsive to corticosteroids following varicella pneumonia. Chest. 1998;113:249–251. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmed R., Ahmed Q.A., Adhami N.A., Memish Z.A. Varicella pneumonia: another ‘steroid responsive’ pneumonia? J Chemother. 2002;14:220–222. doi: 10.1179/joc.2002.14.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shirai T., Sano K., Matsuyama S. Varicella pneumonia in a healthy adult presenting with severe respiratory failure. Intern Med. 1996;35:315–318. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.35.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tokat O., Kelebek N., Turker G., Kahveci S.F., Ozcan B. Intravenous immunoglobulin in adult varicella pneumonia complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Int Med Res. 2001;29:252–255. doi: 10.1177/147323000102900313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dudding B.A., Wagner S.C., Zeller J.A., Gmelich J.T., French G.R., Top F.H., Jr Fatal pneumonia associated with adenovirus type 7 in three military trainees. N Engl J Med. 1972;286:1289–1292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197206152862403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearson R.D., Hall W.J., Menegus M.A., Douglas R.G., Jr. Diffuse pneumonitis due to adenovirus type 21 in a civilian. Chest. 1980;78:107–109. doi: 10.1378/chest.78.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Retalis P., Strange C., Harley R. The spectrum of adult adenovirus pneumonia. Chest. 1996;109:1656–1657. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.6.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klinger J.R., Sanchez M.P., Curtin L.A., Durkin M., Matyas B. Multiple cases of life-threatening adenovirus pneumonia in a mental health care center. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:645–649. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.9608057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Two fatal cases of adenovirus-related illness in previously healthy young adults—Illinois, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:553–5. [PubMed]

- 49.Levin S., Dietrich J., Guillory J. Fatal nonbacterial pneumonia associated with Adenovirus type 4. Occurrence in an adult. JAMA. 1967;201:975–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zarraga A.L., Kerns F.T., Kitchen L.W. Adenovirus pneumonia with severe sequelae in an immunocompetent adult. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:712–713. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levy H., Simpson S.Q. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:1710–1713. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.6.8004332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castillo C., Naranjo J., Sepulveda A., Ossa G., Levy H. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome due to Andes virus in Temuco, Chile: clinical experience with 16 adults. Chest. 2001;120:548–554. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.2.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riquelme R., Riquelme M., Torres A. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, southern Chile. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1438–1443. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.020798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chapman L.E., Ellis B.A., Koster F.T. Discriminators between hantavirus-infected and -uninfected persons enrolled in a trial of intravenous ribavirin for presumptive hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:293–304. doi: 10.1086/324619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chapman L.E., Mertz G.J., Peters C.J. Intravenous ribavirin for hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: safety and tolerance during 1 year of open-label experience. Ribavirin Study Group. Antivir Ther. 1999;4:211–219. doi: 10.1177/135965359900400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aylward R.B., Burdge D.R. Ribavirin therapy of adult respiratory syncytial virus pneumonitis. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:2303–2304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rupp M.E., Schwartz M.L., Bechard D.E. Measles pneumonia. Treatment of a near-fatal case with corticosteroids and vitamin A. Chest. 1993;103:1625–1626. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.5.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haller A., von Segesser L., Baumann P.C., Krause M. Severe respiratory insufficiency complicating Epstein–Barr virus infection: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:206–209. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.1.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.So L.K., Lau A.C., Yam L.Y. Development of a standard treatment protocol for severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1615–1617. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13265-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choi K.W., Chau T.N., Tsang O. Outcomes and prognostic factors in 267 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:715–723. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao Z., Zhang F., Xu M. Description and clinical treatment of an early outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Guangzhou, PR China. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:715–720. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lee N., Hui D., Wu A. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ho J.C., Ooi G.C., Mok T.Y. High-dose pulse versus nonpulse corticosteroid regimens in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1449–1456. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-766OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chan K.S., Lai S.T., Chu C.M. Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome with lopinavir/ritonavir: a multicentre retrospective matched cohort study. Hong Kong Med J. 2003;9:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Loutfy M.R., Blatt L.M., Siminovitch K.A. Interferon alfacon-1 plus corticosteroids in severe acute respiratory syndrome: a preliminary study. JAMA. 2003;290:3222–3228. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.24.3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hsu L.Y., Lee C.C., Green J.A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Singapore: clinical features of index patient and initial contacts. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:713–717. doi: 10.3201/eid0906.030264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wong V.W., Dai D., Wu A.K., Sung J.J. Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome with convalescent plasma. Hong Kong Med J. 2003;9:199–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and coronavirus testing—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52:297–302. [PubMed]

- 69.Update: severe acute respiratory syndrome—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52:332, 334–6. [PubMed]

- 70.Update: severe acute respiratory syndrome—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52:357–60. [PubMed]

- 71.Update: severe acute respiratory syndrome—United States, June 11, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52:550. [PubMed]

- 72.Booth C.M., Matukas L.M., Tomlinson G.A. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. JAMA. 2003;289:2801–2809. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.JOC30885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dolin R. Influenza: current concepts. Am Fam Physician. 1976;14:72–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Falsey A.R., Formica M.A., Treanor J.J., Walsh E.E. Comparison of quantitative reverse transcription-PCR to viral culture for assessment of respiratory syncytial virus shedding. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4160–4165. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.9.4160-4165.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.File T.M. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet. 2003;362:1991–2001. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ruiz-Gonzalez A., Falguera M., Nogues A., Rubio-Caballero M. Is Streptococcus pneumoniae the leading cause of pneumonia of unknown etiology? A microbiologic study of lung aspirates in consecutive patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 1999;106:385–390. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ishida T., Hashimoto T., Arita M., Ito I., Osawa M. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized patients: a 3-year prospective study in Japan. Chest. 1998;114:1588–1593. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.6.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Robbins G.K., De Gruttola V., Shafer R.W. Comparison of sequential three-drug regimens as initial therapy for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2293–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shafer R.W., Smeaton L.M., Robbins G.K. Comparison of four-drug regimens and pairs of sequential three-drug regimens as initial therapy for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2304–2315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jaeckel E., Cornberg M., Wedemeyer H. Treatment of acute hepatitis C with interferon alfa-2b. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1452–1457. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fried M.W., Shiffman M.L., Reddy K.R. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Manns M.P., McHutchison J.G., Gordon S.C. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–965. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lai C.L., Chien R.N., Leung N.W. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. Asia Hepatitis Lamivudine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:61–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807093390201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dienstag J.L., Schiff E.R., Wright T.L. Lamivudine as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis B in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1256–1263. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910213411702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leone P.A., Trottier S., Miller J.M. Valacyclovir for episodic treatment of genital herpes: a shorter 3-day treatment course compared with 5-day treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:958–962. doi: 10.1086/339326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Corey L., Wald A., Patel R. Once-daily valacyclovir to reduce the risk of transmission of genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Balfour H.H., Jr, Rotbart H.A., Feldman S. Acyclovir treatment of varicella in otherwise healthy adolescents. The Collaborative Acyclovir Varicella Study Group. J Pediatr. 1992;120:627–633. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wallace M.R., Bowler W.A., Murray N.B., Brodine S.K., Oldfield E.C., 3rd Treatment of adult varicella with oral acyclovir. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:358–363. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-5-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Salmon-Ceron D., Fillet A.M., Aboulker J.P. Effect of a 14-day course of foscarnet on cytomegalovirus (CMV) blood markers in a randomized study of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with persistent CMV viremia. Agence National de Recherche du SIDA 023 Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:901–905. doi: 10.1086/515223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Martin D.F., Sierra-Madero J., Walmsley S. A controlled trial of valganciclovir as induction therapy for cytomegalovirus retinitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1119–1126. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nicholson K.G., Aoki F.Y., Osterhaus A.D. Efficacy and safety of oseltamivir in treatment of acute influenza: a randomised controlled trial. Neuraminidase Inhibitor Flu Treatment Investigator Group. Lancet. 2000;355:1845–1850. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Treanor J.J., Hayden F.G., Vrooman P.S. Efficacy and safety of the oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir in treating acute influenza: a randomized controlled trial. US Oral Neuraminidase Study Group. JAMA. 2000;283:1016–1024. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hedrick J.A., Barzilai A., Behre U. Zanamivir for treatment of symptomatic influenza A and B infection in children five to twelve years of age: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:410–417. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200005000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eron L.J., Toy C., Salsitz B., Scheer R.R., Wood D.L., Nadler P.I. Therapy of genital herpes with topically applied interferon. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1137–1139. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.7.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Levin M.J., Judson F.N., Eron L. Comparison of intramuscular recombinant alpha interferon (rIFN-2A) with topical acyclovir for the treatment of first-episode herpes genitalis and prevention of recurrences. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:649–652. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.5.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moler F.W., Steinhart C.M., Ohmit S.E., Stidham G.L. Effectiveness of ribavirin in otherwise well infants with respiratory syncytial virus-associated respiratory failure. Pediatric Critical Study Group. J Pediatr. 1996;128:422–428. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Guerguerian A.M., Gauthier M., Lebel M.H., Farrell C.A., Lacroix J. Ribavirin in ventilated respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:829–834. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.9810013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hung IF, Cheng VC, Wu AK, et al. Viral loads in clinical specimens and SARS manifestations. Emerg Infect Dis 2004 in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Koren G., King S., Knowles S., Phillips E. Ribavirin in the treatment of SARS: a new trick for an old drug? CMAJ. 2003;168:1289–1292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ning Q., Brown D., Parodo J. Ribavirin inhibits viral-induced macrophage production of TNF, IL-1, the procoagulant fgl2 prothrombinase and preserves Th1 cytokine production but inhibits Th2 cytokine response. J Immunol. 1998;160:3487–3493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tan E.L., Ooi E.E., Lin C.Y. Inhibition of SARS coronavirus infection in vitro with clinically approved antiviral drugs. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:581–586. doi: 10.3201/eid1004.030458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Smee D.F., Bray M., Huggins J.W. Antiviral activity and mode of action studies of ribavirin and mycophenolic acid against orthopoxviruses in vitro. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2001;12:327–335. doi: 10.1177/095632020101200602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cinatl J., Morgenstern B., Bauer G., Chandra P., Rabenau H., Doerr H.W. Glycyrrhizin, an active component of liquorice roots, and replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Lancet. 2003;361:2045–2046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13615-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cinatl J., Morgenstern B., Bauer G., Chandra P., Rabenau H., Doerr H.W. Treatment of SARS with human interferons. Lancet. 2003;362:293–294. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13973-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen F., Chan K.H., Jiang Y. In vitro susceptibility of ten clinical isolates of SARS coronavirus to selected antiviral compounds. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kumar K.S., Russo M.W., Borczuk A.C. Significant pulmonary toxicity associated with interferon and ribavirin therapy for hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2432–2440. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Haagmans B.L., Kuiken T., Martina B.E. Pegylated interferon-alpha protects type 1 pneumocytes against SARS coronavirus infection in macaques. Nat Med. 2004;10:290–293. doi: 10.1038/nm1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hensley L.E., Fritz L.E., Jahrling P.B., Karp C.L., Huggins J.W., Geisbert T.W. Interferon-beta 1a and SARS coronavirus replication. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:317–319. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Stroher U., DiCaro A., Li Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus is inhibited by interferon-alpha. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1164–1167. doi: 10.1086/382597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]