Abstract

Background

Many smokers give up smoking on their own, but materials that provide a structured programme for smokers to follow may increase the number who quit successfully.

Objectives

The aims of this review were to determine the effectiveness of different forms of print‐based self‐help materials that provide a structured programme for smokers to follow, compared with no treatment and with other minimal contact strategies, and to determine the comparative effectiveness of different components and characteristics of print‐based self‐help, such as computer‐generated feedback, additional materials, tailoring of materials to individuals, and targeting of materials at specific groups.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). The date of the most recent search was March 2018.

Selection criteria

We included randomised trials of smoking cessation with follow‐up of at least six months, where at least one arm tested print‐based materials providing self‐help compared with minimal print‐based self‐help (such as a short leaflet) or a lower‐intensity control. We defined 'self‐help' as structured programming for smokers trying to quit without intensive contact with a therapist.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data in accordance with standard methodological procedures set out by Cochrane. The main outcome measure was abstinence from smoking after at least six months' follow‐up in people smoking at baseline. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence in each study and biochemically validated rates when available. Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model.

Main results

We identified 75 studies that met our inclusion criteria. Many study reports did not include sufficient detail to allow judgement of risk of bias for some domains. We judged 30 studies (40%) to be at high risk of bias for one or more domains.

Thirty‐five studies evaluated the effects of standard, non‐tailored self‐help materials. Eleven studies compared self‐help materials alone with no intervention and found a small effect in favour of the intervention (n = 13,241; risk ratio (RR) 1.19, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03 to 1.37; I² = 0%). We judged the evidence to be of moderate certainty in accordance with GRADE, downgraded for indirect relevance to populations in low‐ and middle‐income countries because evidence for this comparison came from studies conducted solely in high‐income countries and there is reason to believe the intervention might work differently in low‐ and middle‐income countries. This analysis excluded two studies by the same author team with strongly positive outcomes that were clear outliers and introduced significant heterogeneity. Six further studies of structured self‐help compared with brief leaflets did not show evidence of an effect of self‐help materials on smoking cessation (n = 7023; RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.07; I² = 21%). We found evidence of benefit from standard self‐help materials when there was brief contact that did not include smoking cessation advice (4 studies; n = 2822; RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.88; I² = 0%), but not when self‐help was provided as an adjunct to face‐to‐face smoking cessation advice for all participants (11 studies; n = 5365; RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.28; I² = 32%).

Thirty‐two studies tested materials tailored for the characteristics of individual smokers, with controls receiving no materials, or stage‐matched or non‐tailored materials. Most of these studies used more than one mailing. Pooling studies that compared tailored self‐help with no self‐help, either on its own or compared with advice, or as an adjunct to advice, showed a benefit of providing tailored self‐help interventions (12 studies; n = 19,190; RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.49; I² = 0%) with little evidence of difference between subgroups (10 studies compared tailored with no materials, n = 14,359; RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.51; I² = 0%; two studies compared tailored materials with brief advice, n = 2992; RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.49; I² = 0%; and two studies evaluated tailored materials as an adjunct to brief advice, n = 1839; RR 1.72, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.53; I² = 10%). When studies compared tailored self‐help with non‐tailored self‐help, results favoured tailored interventions when the tailored interventions involved more mailings than the non‐tailored interventions (9 studies; n = 14,166; RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.68; I² = 0%), but not when the two conditions were contact‐matched (10 studies; n = 11,024; RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.30; I² = 50%). We judged the evidence to be of moderate certainty in accordance with GRADE, downgraded for risk of bias.

Five studies evaluated self‐help materials as an adjunct to nicotine replacement therapy; pooling three of these provided no evidence of additional benefit (n = 1769; RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.30; I² = 0%). Four studies evaluating additional written materials favoured the intervention, but the lower confidence interval crossed the line of no effect (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.58; I² = 73%). A small number of other studies did not detect benefit from using targeted materials, or find differences between different self‐help programmes.

Authors' conclusions

Moderate‐certainty evidence shows that when no other support is available, written self‐help materials help more people to stop smoking than no intervention. When people receive advice from a health professional or are using nicotine replacement therapy, there is no evidence that self‐help materials add to their effect. However, small benefits cannot be excluded. Moderate‐certainty evidence shows that self‐help materials that use data from participants to tailor the nature of the advice or support given are more effective than no intervention. However, when tailored self‐help materials, which typically involve repeated assessment and mailing, were compared with untailored materials delivered similarly, there was no evidence of benefit.

Available evidence tested self‐help interventions in high‐income countries, where more intensive support is often available. Further research is needed to investigate effects of these interventions in low‐ and middle‐income countries, where more intensive support may not be available.

Plain language summary

Do printed self‐help materials help people to quit smoking?

Background

We reviewed the evidence showing how effective printed self‐help materials are in helping people to quit smoking. We looked for studies of any type of printed self‐help that gave structured support and advice about quitting. This could include any booklets, leaflets, or information sheets that set out some kind of structured programme that someone could follow to help them quit smoking. We also included self‐help in audio or video format, but we did not include internet programmes or other formats. We were interested in the number of people who were not smoking for at least six months from the time they were given the self‐help materials. Studies had to include people who smoked, but those people did not need to be currently trying to quit smoking.

Study characteristics

We searched electronic databases for studies that investigated printed self‐help. We ran our most recent search in March 2018, and so far we have found 75 studies. Most studies took place in North America or Europe and were carried out with adults, although they did not require that people wanted to quit smoking to join. Studies delivered self‐help materials in person or by post, some all at once, and some spread out over the length of the study. In most studies, self‐help was the only support people were given, but some studies tested self‐help given with other kinds of support to test whether there was any extra benefit from written self‐help. Some studies gathered information about individual smokers, so they could tailor self‐help to better help them.

Key results

Eleven studies including over 13,000 people provided evidence of a small benefit of printed self‐help materials when provided on their own. Our confidence in this evidence was only moderate, because these studies took place in high‐income countries, which makes them less relevant to people from lower‐income countries, who might benefit differently. When people used self‐help as well as receiving face‐to‐face advice on how to stop smoking (11 studies), there was no extra benefit compared with the effect of that advice without printed self‐help.

Thirty‐two studies provided written self‐help that was individually tailored, comparing it with either non‐tailored self‐help or nothing. Evidence based on ten studies including nearly 15,000 people showed that tailored self‐help was more helpful than nothing. Our confidence in this evidence is moderate, because some of these studies might have had problems in the ways they were carried out that could have affected the results.

Conclusions

When no other support is available, written self‐help materials help more people to stop smoking compared with getting no help at all. People were more likely to make successful quit attempts when they were also given face‐to‐face support or nicotine replacement therapy, but printed self‐help did not make these people more likely to quit.

Self‐help materials that were tailored to help individual people are more effective than no help at all. However, tailoring these materials often involves more contact with the research team, and when we compared tailored self‐help with regular self‐help that involved the same amount of contact, we did not find a difference in quit rates.

The studies we found looked at self‐help given to people in high‐income countries, where more intensive support is often available. More research is needed to find out how well self‐help works for people in low‐ and middle‐income countries, where more intensive support is less available.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Print‐based self‐help compared to no materials for smoking cessation.

| Print‐based self‐help compared to no materials for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: people who smoke; not selected for interest in quitting smoking Settings: community ‐ materials provided without personal contact Intervention: print‐based self‐help materials Comparison: no materials | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No materials | Print‐based self‐helpmaterials | |||||

| Abstinence ‐ non‐tailored self‐help Follow‐up: 6+ months | Moderate‐risk population1 | RR 1.19 (1.03 to 1.37) | 13,241 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3 | No evidence of effect detected in other studies where the controls received other materials (n = 6), or wher all participants had personal contact (n = 5) or received brief advice (n = 11) | |

| 50 per 1000 | 60 per 1000 (52 to 69) | |||||

| Abstinence ‐ individually tailored self‐help Follow‐up: 6+ months | Moderate‐risk population1 | RR 1.34 (1.19 to 1.51) | 14,359 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | ||

| 50 per 1000 | 81 per 1000 (71 to 91) | |||||

| CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Control group success rate based on average across studies. Low rate reflects intervention in participants not selected on basis of motivation to quit. All studies conducted in high‐income countries. 2Most studies at high or unclear risk of bias, but no evidence of differential effect based on risk of bias. Not downgraded. 3Downgraded one level for indirectness: indirectly relevant to populations in low‐ and middle‐income countries because evidence for this comparison came from studies conducted solely in high‐income countries, and there is reason to believe the intervention might work differently in low‐ and middle‐income countries. 4Downgraded one level for risk of bias: all but one study at high or unclear risk of bias. One study at low risk of bias was small with wide confidence intervals.

Background

Description of the condition

The World Health Organization has identified tobacco use as the leading behavioural risk factor for preventable premature death (WHO 2012). Globally, tobacco smoking is currently estimated to cause the death of about seven million people a year (WHO 2017). More than 80% of tobacco‐related deaths are projected to occur in low‐ and middle‐ income countries (WHO 2012). Adverse health effects from tobacco use include cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and cancer.

Description of the intervention

The aim of self‐help interventions is to provide some of the benefits of intensive behavioural interventions without the need to attend treatment sessions. Such materials can be disseminated and used on a much wider scale than therapist‐delivered treatment. They therefore represent a bridge between the clinical approach to smoking cessation oriented towards individuals and public health approaches that target populations (Curry 1993). Self‐help programmes were first developed as written materials, primarily delivered in print, but other formats such as videos and audiotapes have also been used. New technologies enable delivery of information and support via the internet and mobile phones; separate Cochrane Reviews have evaluated these self‐help formats (Taylor 2017; Whittaker 2016).

How the intervention might work

Self‐help materials provide structured programmes and advice aimed at helping people to quit smoking by following the programmes therein. These materials and programmes can have a theoretical basis or can be tailored to the individuals trying to quit. Printed self‐help materials represent a low‐cost intervention with potentially wide reach.

Why it is important to do this review

Behavioural strategies to aid smoking cessation range from very brief interventions, such as advice from a physician, to intensive multi‐component programmes. There is good evidence supporting the effectiveness of brief, therapist‐delivered interventions, such as physician advice (Stead 2013a), as well as the additional effect of more intensive behavioural interventions, such as group therapy (Stead 2017), individual counselling (Lancaster 2017), and telephone counselling (Stead 2013b). However, a major limitation of therapist‐delivered behavioural interventions is that they reach only a small proportion of smokers. Most successful quitters give up on their own (Lee 2007). Methods to support otherwise unaided quit attempts therefore have the potential to help a far greater proportion of the smoking population. This is especially the case in lower‐income countries, where more intensive cessation support may not be available.

Previous reviews and versions of this review have found evidence of a small but significant effect of print‐based self‐help interventions. However, new theories and technologies have led to continued interest and research in this field. In particular, the ability to tailor materials based on individual characteristics through computer‐based algorithms. Such personalisation is the focus of most new research in this field.

The aim of this review is to summarise existing evidence for print‐based, video, and audiotape forms of self‐help interventions in promoting smoking cessation.

Objectives

The aims of this review were to determine the effectiveness of different forms of print‐based self‐help materials that provide a structured programme for smokers to follow, compared with no treatment and with other minimal contact strategies, and to determine the comparative effectiveness of different components and characteristics of print‐based self‐help, such as computer‐generated feedback, additional materials, tailoring of materials to individuals, and targeting of materials at specific groups.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We sought randomised controlled trials with a minimum follow‐up of six months, where at least one arm comprised a print‐based self‐help intervention without repeated face‐to‐face therapist contact compared with another print‐based self‐help intervention or with a minimal control. We included studies that allocated participants to treatment via a quasi‐randomised method, but, where appropriate, we used sensitivity analysis to determine whether inclusion of these studies altered the results.

Types of participants

We included any smokers except pregnant smokers and adolescent smokers. Separate Cochrane Reviews have evaluated interventions in pregnant smokers (Coleman 2015; Chamberlain 2017), and in adolescent smokers (Fanshawe 2017).

Types of interventions

We defined a 'self‐help intervention' as any manual or programme designed to be used by individuals to assist a quit attempt not aided by health professionals, counsellors, or group support. This review primarily covers written materials such as booklets and leaflets, but information could also have been provided via audio or video or a similar medium. Separate reviews cover interventions designed to be delivered via the internet, or via mobile phone (Taylor 2017; Whittaker 2016). Materials could be aimed at smokers in general; could target particular populations of smokers, for example, those of different ages or ethnic groups; or could be tailored to individual smoker characteristics. We did not include brief leaflets on the health effects of smoking ‐ we considered them to be a control intervention if compared with a more substantial manual. We considered interventions with a single session of minimal face‐to‐face contact for the purpose of supplying the self‐help programme materials as self‐help alone. Where a face‐to‐face meeting included discussion of programme content, we categorised this as brief advice in addition to self‐help materials. We excluded interventions that provided repeated sessions of advice in addition to self‐help materials. Separate Cochrane Reviews cover telephone counselling or hotlines as adjuncts to self‐help materials (Stead 2013b), and interventions aimed at relapse prevention (Hajek 2013).

Types of outcome measures

We used sustained abstinence, or point prevalence, where available. We included studies that used self‐report of cessation alone or biochemically validated cessation.

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified studies included in previous reviews and meta‐analyses, and we searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group Specialised Register of controlled trials for additional studies, using the terms self‐help*, manual*, booklet*, or pamphlet* in the title or abstract, or as a keyword (Appendix 1). We conducted the most recent search of the Register in March 2018. At the time of the search, the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 1) in the Cochrane Library; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20180209; Embase (via OVID) to week 201807; and PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20180212. See the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group website for full search strategies and a list of other resources searched.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (JLB and JMOM) extracted data. Information extracted included details of the intervention, population recruited, method of randomisation, completeness of follow‐up, way in which cessation was defined, and whether self‐reported cessation was validated.

We summarised individual study results as a risk ratio (RR), calculated as: (number of quitters in intervention group/number randomised to intervention group)/(number of quitters in control group/number randomised to control group). Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis using a Mantel‐Haenszel random‐effects method to estimate a pooled risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We estimated statistical heterogeneity between studies using the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). Values between 30% and 60% may suggest moderate heterogeneity, and values over 75% represent considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

We categorised studies according to the amount of face‐to‐face contact provided to both treatment and comparison intervention groups, whether or not any written materials were given to the comparison group, and whether the material was individually tailored. Comparison tables included the following.

Non‐tailored self‐help materials versus no treatment or a leaflet only, without face‐to‐face contact.

Non‐tailored self‐help materials versus no treatment or a leaflet only, with face‐to‐face contact.

Non‐tailored self‐help materials and brief advice versus brief advice alone.

Individually tailored materials versus no materials.

Individually tailored versus standard or stage‐matched materials.

Self‐help materials plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) versus NRT alone.

A Cochrane Review on individual counselling covered any studies comparing self‐help to individual counselling (Lancaster 2017). The Cochrane Review on group therapy for smoking cessation covered self‐help versus group counselling (Stead 2017). Self‐help plus NRT versus self‐help alone is a test of the efficacy of NRT; a Cochrane Review on NRT versus control covers this topic (Hartmann‐Boyce 2018).

Comparison tables also addressed the following enhancements and adjuncts to self‐help.

Tailored self‐help programmes versus non‐tailored programmes, or no‐intervention controls.

Targeted materials versus standard materials.

Provision of additional materials.

Different self‐help programmes or different media formats (e.g. audio, video) compared to each other.

We define 'tailored materials' as those that make use of participant characteristics to provide individualised programmes. We also include in this category interventions providing individual written feedback in addition to standard materials. We define 'targeted materials' as those tailored for a broadly defined category of smokers, for example, women with young children, older smokers, or smokers at a particular stage of change (Kreuter 2000).

Earlier versions of this review included telephone counselling and relapse prevention interventions. A separate Cochrane Review evaluated the use of proactive telephone counselling or provision of telephone hotlines as an adjunct to self‐help materials (Stead 2013b), so we did not include in this review studies that compare only these interventions. Likewise, Hajek 2013 evaluated interventions aiming to prevent relapse, so we have no longer included them in this review.

'Summary of findings' table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table for our primary outcomes, in accordance with standard Cochrane methods. We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of evidence for each outcome.

Results

Description of studies

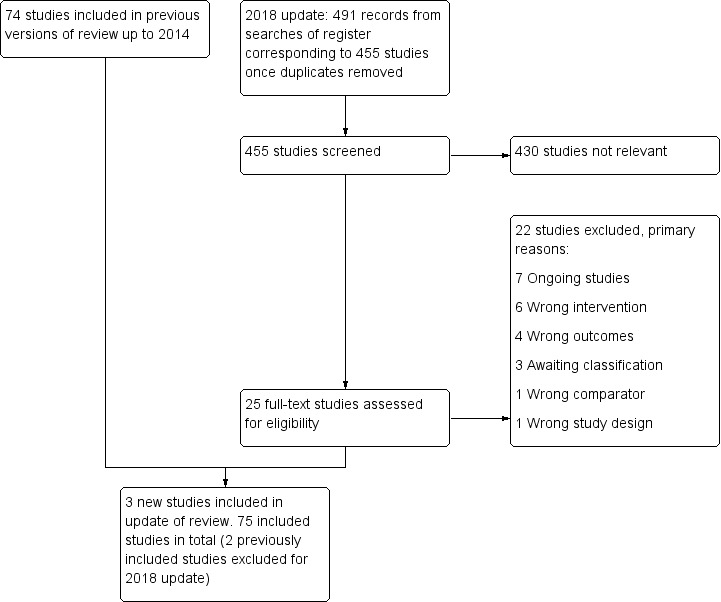

For the present update of this review, we identified 491 potentially relevant records new to the Tobacco Addiction Group Specialised Register since the last update; three new studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The review now includes 75 studies of self‐help methods. We treated one study with a factorial design as two studies for data entry purposes (Killen 1997; Killen 1997 +NP). Thirty‐four of the included studies compared standard self‐help materials with no intervention or provided standard materials as an adjunct to advice. The other studies compared targeted or tailored self‐help methods or compared other variations of programmes. Some studies used multiple interventions, testing the effects of different types of information or of increasing amounts of material. Studies of self‐help materials were carried out in a range of settings. Some studies provided the materials without face‐to‐face contact or any additional motivating strategy. Some studies tested the use of materials for people who had called quitlines (self‐help materials were the main form of support offered) or the use of materials as an adjunct to counselling (Strecher 2005). In healthcare settings, studies more frequently provided self‐help materials as an adjunct to brief advice to quit. Some studies described as testing self‐help materials included relatively high levels of face‐to‐face support, although less than in formal counselling programmes. Most studies did not specify an interest in quitting as a selection criterion.

1.

Flow diagram for 2018 update.

The content and format of the self‐help programmes varied. The most frequently used materials were the American Lung Association (ALA) cessation manual: Freedom from Smoking in 20 days, and the maintenance manual: A Lifetime of Freedom from Smoking. Most other programmes were not named or described fully. Materials have tended to become more complex over time and to incorporate more techniques from behaviour therapy approaches. Most recent studies have used computerised expert systems to provide tailored materials judged to be relevant to the characteristics of each smoker, using baseline data. We specified that materials should contain a structured programme for quitting. When it was not clear whether the materials provided met these criteria, we performed sensitivity analysis to determine the effects of including or excluding these studies.

Fraser 2014 factorially tested combinations of ‘on’ and ‘off’ versions of five interventions: the National Cancer Institute website versus a ‘lite’ website, telephone counselling versus no counselling, a self‐help manual versus a brief brochure, motivational email messages versus no messages, and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) versus no NRT. We were interested in two comparisons from this study. The first compared the arm comprising the ‘off’ version of each intervention except the self‐help manual with the arm comprising the ‘off’ version of every intervention. The second compared the arm comprising the ‘off’ version of each intervention except the self‐help manual and NRT with the arm comprising the ‘off’ version of each intervention except NRT. Unfortunately the study report did not report abstinence rates for these comparisons, and when we contacted the study author team, we received no response. As such, we were unable to include this study in the relevant meta‐analyses.

Further details on each of the included studies can be found in the Characteristics of included studies tables. Details of 79 studies excluded at full‐text stage can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables. The most common reasons for listing studies as excluded are that study authors used self‐help materials as the control, and follow‐up was too short ‐ typically only one month. We previously included Killen 1990 and Fortmann 1995 in this review, but we excluded them from this update on the grounds that they are studies of relapse prevention and are now included in another Cochrane Review (Hajek 2013). Details of seven ongoing studies and three studies for which there was insufficient information to include or exclude are presented in the Characteristics of ongoing studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables respectively.

Non‐tailored self‐help materials compared to no intervention (Comparisons 1 and 2)

Non‐tailored materials without face‐to‐face contact

We identified 20 studies that sent non‐tailored self‐help materials to smokers without any personal contact. Thirteen of these sent no materials to the comparison control group (Cuckle 1984; Ledwith 1984; Lando 1991; Gritz 1992; Pallonen 1994; Curry 1995; Humerfelt 1998; Dijkstra 1999; Schofield 1999; Becona 2001a; Becona 2001b; Lennox 2001; Willemsen 2006). In the other seven studies, the control group received a brief leaflet (Davis 1984; Cummings 1988; Orleans 1991; Lichtenstein 2000; Lichtenstein 2008; Fraser 2014; Parekh 2014). In 11 studies, participants responded to promotion of smoking cessation programmes or volunteered for a trial. One of these recruited only smokers who were not planning to quit in the next six months (Dijkstra 1999). Two studies sent unsolicited materials to smokers in health maintenance organisations (Gritz 1992; Curry 1995). One sent either tailored or non‐tailored letters from a physician to general practice patients who had answered a questionnaire about smoking behaviour (Lennox 2001); we compared the standard letter with the non‐intervention control in this comparison. One study addressed smoking, diet, physical activity, and weight, so only a subgroup of participants smoked; the control group received information on other health behaviours (Parekh 2014). One study sent a booklet and a personally addressed letter from a consultant to smokers or recent quitters discharged from hospital (Schofield 1999). Three studies targeted factors that might motivate interest in quitting. One of these used a community survey to identify young (aged 30 to 45 years) male smokers with reduced forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁) or asbestos exposure. The intervention consisted of self‐help materials accompanied by a letter from a respiratory physician, which drew attention to the individual's higher risk of smoking‐related lung disease and advised quitting (Humerfelt 1998). Two recruited households via a utility bill enclosure offering radon testing, and provided a leaflet (Lichtenstein 2000) or video (Lichtenstein 2008) that highlighted the synergistic impact of radon and smoking and advised on quitting or not smoking indoors. The comparison groups received a standard leaflet about the risks of radon that did not emphasise quitting. Fraser 2014 recruited people visiting a quit smoking website. All but four studies used a single mailing of materials. Becona 2001a and one arm of Becona 2001b sent six weekly mailings; Pallonen 1994 sent stage of change‐based manuals at six‐monthly intervals; one arm of Parekh 2014 received a second assessment and mailing after three months.

Fraser 2014 comprised 32 arms testing combinations of ‘on’ and ‘off’ versions of five interventions and included a comparison of self‐help materials with a minimal brochure. However, because of insufficient data, we were unable to include this study in the analysis.

Non‐tailored materials with brief contact

We identified four studies in which investigators gave non‐tailored self‐help materials personally to participants, but not in the context of formal advice to stop smoking. One study gave the control group health education materials without a specific focus on tobacco use, and intended to give the intervention group a single telephone call (Resnicow 1997). In the other studies, controls received no intervention (Prue 1983; Campbell 1986; Betson 1998). Three studies recruited in outpatient clinics (Prue 1983; Campbell 1986; Betson 1998); the last of these probably included some telephone contact for the self‐help group, although the extent of this is unclear. Resnicow 1997 recruited in healthcare, church, and public housing settings.

Non‐tailored materials and advice versus advice alone

Eleven studies assessed non‐tailored self‐help materials as an adjunct to brief advice about stopping smoking given by a healthcare worker. Three of these studies gave some written materials to the control group. Lando 1988 prescribed nicotine gum to both arms and gave instructions on its use. A doctor alone gave advice in six studies, and a doctor, nurse, or both gave advice in four. In Davies 1992, student nurses advised two smokers each ‐ one before and one after training ‐ to deliver a self‐help manual. Hollis 1993 provided self‐help participants with additional advice from a nurse, as well as a physician message. In a study of physician advice that used a complete factorial design, some participants received structured advice with or without materials, and some received brief advice ‐ we have combined the two levels of advice (Thompson 1988). Kottke 1989 randomised physicians to a workshop with or without a supply of self‐help materials for their patients.

We did not identify any studies that directly compared standard self‐help materials with brief advice.

Tailored self‐help materials (Comparisons 3 and 4)

Thirty‐two studies used materials tailored to the characteristics of individual smokers. Only two of these provided any face‐to‐face contact as part of the baseline intervention (Lipkus 1999; Meyer 2012). Four recruited people who had called a quitline. Borland 2003 recruited only those callers seeking written materials without counselling. Borland 2004 provided brief counselling to some participants before recruitment, and Strecher 2005 and Sutton 2007 ensured that all participants received counselling during their initial call. Just under half of the remaining studies included volunteers who were likely to have been seeking help to quit. Fifteen recruited a mix of people, some of whom were not interested in immediate quit attempts (Velicer 1999; Curry 1995; Lennox 2001; Prochaska 2001a; Prochaska 2001b; Etter 2004; Aveyard 2003; Prochaska 2004; Prochaska 2005; de Vries 2008; Schumann 2008; Meyer 2012; van der Aalst 2012; Gilbert 2013; Parekh 2014). Dijkstra 1999 specifically recruited people not interested in quitting, and Meyer 2016 recruited people not interested in quitting in the next six months. Four studies evaluated multiple risk factor interventions, so only a subgroup of participants smoked (Prochaska 2004; Prochaska 2005; de Vries 2008; Parekh 2014).

Ten studies compared tailored materials with no intervention (Dijkstra 1998b; Prochaska 2001a; Prochaska 2001b; Etter 2004; Prochaska 2004; Prochaska 2005; Meyer 2008; Schumann 2008; Hoving 2010; Meyer 2016). Some of the 19 studies testing the incremental effect of tailoring over standard materials confounded the tailoring with additional contact, so we grouped these studies according to whether or not the number of mailings was matched. Ten studies matched contacts (Burling 1989; Owen 1989; Velicer 1999; Becona 2001a; Lennox 2001; Strecher 2005; Velicer 2006; Sutton 2007; de Vries 2008; van der Aalst 2012). Among studies with additional contacts, some provided the same materials initially but then provided additional tailored materials to the intervention group; six tailored all materials (Curry 1991; Prochaska 1993; Curry 1995; Aveyard 2003; Borland 2003; Gilbert 2013), and three tailored materials only in part (Ledwith 1984; Dijkstra 1999; Borland 2004). Two studies tested tailored materials as an adjunct to advice (Lipkus 1999; Meyer 2012). Webb 2013 compared a placebo tailored intervention (tailoring was not actually conducted, but materials were constructed to suggest it had been) with a standard, non‐tailored intervention.

The method used for obtaining information, the theoretical basis for tailoring materials, the materials provided, and the number of contacts, all varied, and are reported in more detail in the Characteristics of included studies tables. Ten studies tailored materials based only on information provided at baseline (Ledwith 1984; Owen 1989; Dijkstra 1998a; Curry 1995; Lennox 2001; Strecher 2005; Sutton 2007; de Vries 2008; Hoving 2010; van der Aalst 2012), whereas the others sent further materials based on further assessments. Of those interventions that reported the theoretical basis for tailoring, stage of change was by far the most commonly used model, with 15 interventions modelling material on this theory (Pederson 1983; Velicer 1999; Lennox 2001; Prochaska 2001a; Prochaska 2001b; Aveyard 2003; Borland 2003; Etter 2004; Prochaska 2004; Prochaska 2005; Velicer 2006; Meyer 2008; Schumann 2008; Meyer 2012; Meyer 2016). Sutton 2007 tailored materials based on social‐cognitive and perspectives of change theories, and two studies based their intervention on the I‐change model (Dijkstra 1998a; Hoving 2010). Most tailored interventions provided materials at multiple time points.

Self‐help and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) compared to NRT alone (Comparison 5)

Lando 1988 tested non‐tailored self‐help materials as an adjunct to nicotine replacement. Fraser 2014 comprised 32 arms testing combinations of ‘on’ and ‘off’ versions of five interventions and included a comparison of self‐help materials plus NRT with a minimal brochure plus NRT. However, because of insufficient data, we were unable to include the study in our analysis. We also excluded ICRF 1994 from this comparison because both groups received written materials that we classified as self‐help. For this update, we excluded a study previously included in the review for this comparison because the intervention was targeted at relapse prevention (Fortmann 1995).

Two studies tested tailored/targeted self‐help materials as an adjunct to NRT. One study, published as an abstract (Orleans 2000), used a guide targeted for older smokers and seven age‐tailored computer‐generated mailings as an adjunct to nicotine patches. The control group received a fact sheet on patch‐assisted quitting. Velicer 2006 tested a single tailored letter as an adjunct to stage‐based manuals and nicotine patches for people identified as ready to quit.

Other enhancements or adjuncts to self‐help materials (Comparison 6)

Additional written materials

Four studies examined the effect of further mailings of non‐tailored materials. Owen 1989 compared a quit kit and five‐day cessation plan with a staged correspondence course. McFall 1993 tested the American Lung Association (ALA) manual: Freedom from Smoking in 20 Days, used in conjunction with a televised programme, compared with additional maintenance newsletters and with the manual or programme alone. Cuckle 1984 mailed the materials six months after the quit kit. Brandon 2016 tested two programmes of additional written materials compared with a single mailing. One arm received 19 mailings over 18 months from baseline, and one received eight mailings over 12 months. We added each arm to the meta‐analysis separately.

Additional video

Killen 1997 tested a video as an additional component. Using a factorial design, investigators also tested the effect of nicotine patches, and because there was evidence of an interaction between the NRT and the self‐help condition, we entered the patch and placebo arms separately.

Materials targeted at particular populations of smokers

Five studies compared a manual targeted at a particular population with a standard one. Davis 1992 compared a programme intended for mothers of young children with ALA or National Cancer Institute (NCI) materials. Orleans 1998 compared a guide addressing the quitting needs and barriers of African American smokers with a standard guide that was mailed to smokers calling the NCI Cancer Information Service. Prochaska 1993 provided manuals tailored to smokers' stage of change compared to standard materials. We excluded another study of manuals tailored to older smokers because no long‐term follow‐up has been reported (Rimer 1994). Nollen 2007 compared culturally sensitive materials with standard materials for African American smokers, who also received nicotine patches and two phone calls.

Comparisons between different types of self‐help materials

We identified eight studies that compared different types of self‐help materials that were neither tailored nor personalised, or were delivered over different time periods (Glasgow 1981; Omenn 1988; ICRF 1994; Berman 1995; Becona 2001b; Sykes 2001; Clark 2004; Smith 2004). Two of these studies compared three different sets of materials (Glasgow 1981; Omenn 1988). ICRF 1994 compared a standard 16‐page booklet with a larger manual containing more information about quitting with the use of nicotine patches. Berman 1995 compared two types of materials for smokers volunteering for heart health screening and smoking cessation. Becona 2001b compared a manual with a weekly mailing of six booklets, both based on the same cognitive‐behavioural approach. Sykes 2001 compared a cognitive‐behavioural programme consisting of a handbook, reduction cards, a progress chart, and an audiotape that summarised the programme and provided relaxation music, with a leaflet developed by the UK Health Education Authority, both used as an adjunct to a single introductory session in a group format. Clark 2004 tested a handout listing internet sites providing useful resources, compared with standard self‐help materials. Smith 2004 compared a 44‐page booklet produced by the Canadian Cancer Society with a single‐page advice pamphlet. These were tested using a factorial design, along with telephone counselling of two different intensities (which we collapsed for this review).

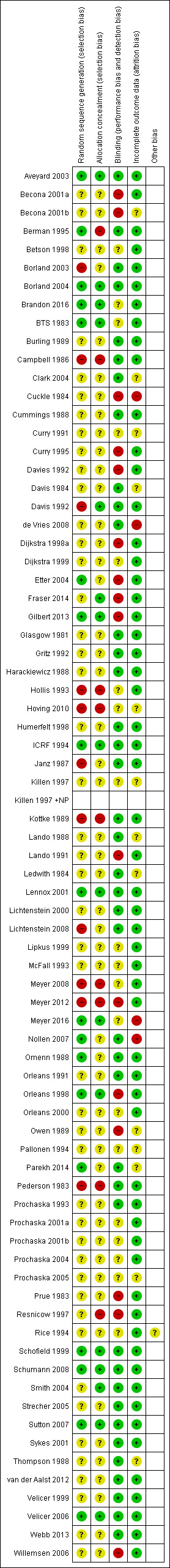

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 shows risk of bias judgements for each included study. We have summarised judgements by domain below. We judged 30 studies to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain, 37 to be at unclear risk of bias in at least one domain and not high in any domain, and eight studies to be at low risk of bias across all domains.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Only 11 study reports provided full descriptions of randomisation and allocation concealment methods that we judged to have low risk of bias (BTS 1983; ICRF 1994;Schofield 1999; Lennox 2001; Aveyard 2003; Borland 2004; Smith 2004; Velicer 2006; Sutton 2007; Schumann 2008; Gilbert 2013). Most studies did not explicitly describe the way in which the randomisation sequence was generated or concealed until participant enrolment. Many studies provided no face‐to‐face contact with participants, and the likelihood of biased allocation was probably low. Four studies used a pseudo‐random method of allocation by day or week of attendance (Pederson 1983; Campbell 1986; Davis 1992; Meyer 2008), and Hollis 1993 used numbers in the patient record. Borland 2003 shuffled questionnaires, and Hoving 2010 used the pre‐printed colour on the questionnaire to determine allocation. Kottke 1989 randomised physicians to intervention groups, and two studies randomised households (Lichtenstein 2000; Lichtenstein 2008). Three studies randomised by recruitment site (Berman 1995; Resnicow 1997; Meyer 2012). For some studies, we judged that the method of generating the allocation could have led to selection bias in the recruitment or assignment of participants. Excluding studies that we judged to be at risk of bias due to an inadequate method of allocation did not alter the conclusions from any meta‐analysis.

Blinding

For this update, we assessed performance and detection bias based on blinding of participants and personnel and on whether biochemical validation was used. Forty‐two studies provided details of blinding, biochemical validation, and/or description of interventions of similar intensity that led us to judge them to be at low risk of bias in this domain. Fifteen studies described procedures that we judged to place the results at high risk of bias in this domain (Prue 1983; Cuckle 1984; Owen 1989; Lando 1991; Davies 1992; Curry 1995; Resnicow 1997; Dijkstra 1998a; Orleans 1998; Becona 2001a; Becona 2001b; Etter 2004; Willemsen 2006; Meyer 2012; Gilbert 2013; Fraser 2014), and the remainder did not provide sufficient detail with which to judge; hence we judged them to be at unclear risk of performance and detection bias.

Twenty‐three studies undertook biochemical validation of all self‐reports of quitting, or provided sufficient data to adjust quit rates for the level of misreport in a sample (Glasgow 1981; BTS 1983; Cuckle 1984; Campbell 1986; Harackiewicz 1988; Omenn 1988; Burling 1989; Kottke 1989; Curry 1991; Orleans 1991; Davies 1992; Hollis 1993; ICRF 1994; Killen 1997; Humerfelt 1998; Schofield 1999; Sykes 2001; Becona 2001a; Lennox 2001; Aveyard 2003; Clark 2004; Nollen 2007; Webb 2013). In three cases, a significant other confirmed quitting (Prue 1983; Cummings 1988; Davis 1992). Amongst those that did not report fully biochemically verified quit rates, 15 studies used self‐reported abstinence at a single follow‐up point (Pederson 1983; Prue 1983; Janz 1987; Thompson 1988; Owen 1989; Lando 1991; Resnicow 1997; Orleans 1998; Dijkstra 1999; Lipkus 1999; de Vries 2008; Hoving 2010 (GP arms only); Gilbert 2013; Meyer 2012; Parekh 2014 (single arms only)). In the other studies without validation, participants classified as non‐smokers had reported sustained abstinence or had been abstinent at one or more points before final follow‐up.

Incomplete outcome data

Some reports give quit rates based only on those people contacted at follow‐up. In this review, we have followed the methods of the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group in reporting analyses based on the total number randomised wherever possible, with dropouts and participants lost to follow‐up classified as smokers. It has been argued in population‐based studies that it may be pessimistic, and may introduce bias, to classify all dropouts as continuing smokers if those data are missing at random (Velicer 1999). We have noted in the 'Risk of bias' tables the number of dropouts by group, and whether the data used in this review included all randomised participants. Where the proportion of dropouts was high and differed across treatment conditions, we performed sensitivity analyses to assess whether excluding dropouts would affect the conclusions. It should be noted that if the proportion of dropouts is similar across conditions, including losses as treatment failures does not affect the risk ratio. A large majority of included studies reported sufficiently similar losses to follow‐up across arms that we judged them to be at low risk of attrition bias. Thirteen did not provide sufficient detail with which to judge, and four reported data on loss to follow‐up that led us to place these studies at high risk of bias in this domain: Nollen 2007 successfully followed up on less than half of participants; two studies reported follow‐up substantially different between intervention and control arms (Cuckle 1984; Meyer 2016); and de Vries 2008 reported only participants who provided data at final follow‐up.

Measures of abstinence

Studies reported a range of measures of abstinence. A minimum follow‐up period of six months was required for inclusion in this review, but 47 of 75 (62.7%) followed up on participants for 12 months or longer. Thirty‐four of these required abstinence to be sustained for a period. Studies that used strict criteria for self‐reported sustained abstinence, with validation at one or more follow‐up points, tended to report lower quit rates for both experimental and comparison interventions. In minimal contact programmes, researchers often reported that obtaining saliva samples for biochemical validation was a problem. Participants may have declined to provide samples for reasons unrelated to their smoking status. Validated quit rates therefore may be particularly low and are likely to underestimate success rates if all those for whom samples are not available are classified as smokers. Measures using abstinence from the first follow‐up may underestimate the long‐term effect of having access to the self‐help materials, which may prompt a quit attempt some time after they were supplied. Studies with long follow‐up that use only point prevalence abstinence rates may show a trend toward increasing quit rates as more smokers make attempts over time.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

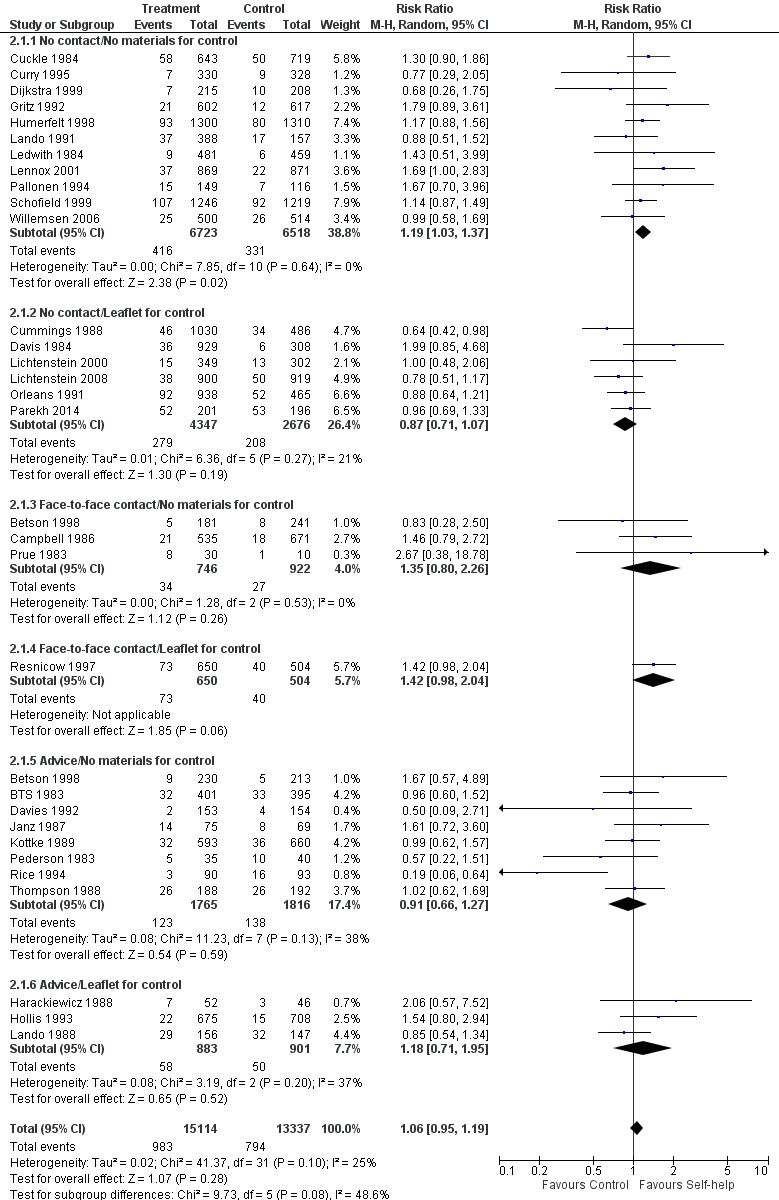

Studies varied in the amount of face‐to‐face contact given with both experimental and comparison interventions, and in whether or not control materials were given to smokers in the comparison group. In considering the effects of self‐help, we grouped studies by these categories. For Comparison 1, we calculated a pooled risk ratio (RR) separately for each level of personal contact with subgroups for the type of control. For Comparison 2, we used the same study data and pooled all subgroups to estimate an overall pooled RR from all studies comparing self‐help with no self‐help.

Non‐tailored self‐help materials compared to no intervention (Comparisons 1 and 2)

Non‐tailored materials without face‐to‐face contact

Thirteen studies with a total of over 15,500 participants provided standard non‐tailored self‐help manuals or materials by post; control groups received no materials. Substantial heterogeneity (I² = 71%) was attributable to the inclusion of two studies conducted in Spain that showed very strong effects (Analysis 1.2) (Becona 2001a; Becona 2001b). Both studies enrolled treatment‐seeking smokers, and those in the control group knew they would be offered treatment after six months ‐ a possible disincentive to making an unaided quit attempt. Quit rates were also very high in the intervention groups (16% and 25%). We have therefore excluded these studies from this meta‐analysis and calculated a pooled estimated effect for the other 11 studies, amongst which we found no evidence of heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Our meta‐analysis also excluded Fraser 2014, for which we were unable to access sufficient data; however, the study report suggests that no significant effect was detected for a standard self‐help brochure compared to no intervention. Amongst the studies included in our meta‐analysis, the control quit rate ranged from 1% to 11%, with an average of 5%, and the intervention quit rate ranged from 2% to 10%. The pooled risk ratio favoured self‐help interventions, although the confidence interval (CI) only narrowly excluded 1.0 (n = 13,241; risk ratio (RR) 1.19, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.37; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.1.1/Analysis 2.1.1).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Non‐tailored self‐help vs no self‐help, pooled by amount of contact, Outcome 2 Neither group had face‐to‐face contact (Becona studies only).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Non‐tailored self‐help vs no self‐help, pooled by amount of contact, Outcome 1 Neither group had face‐to‐face contact (long‐term abstinence).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Non‐tailored self‐help vs no self‐help, pooling all studies, Outcome 1 Long‐term abstinence.

Six studies provided controls with some form of written materials and did not show benefit of more structured materials (n = 7023; RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.1 to 1.07; I² = 21%; Analysis 1.1.2/Analysis 2.1.2). Pooling these two subgroups does not demonstrate benefit of self‐help materials (n = 20,264; RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.20; I² = 26%).

Non‐tailored materials with brief contact

Four studies including almost 3000 participants delivered materials in person rather than by post. The average control group quit rate was 4.7%. Results show no evidence of heterogeneity, and whilst we failed to find evidence of a significant effect of self‐help materials given with face‐to‐face contact when subgrouped based on whether or not controls received some written materials, the pooled result of all four studies did provide evidence of an effect (n = 2822; RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.88; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Non‐tailored self‐help vs no self‐help, pooled by amount of contact, Outcome 3 Both groups had face‐to‐face contact (long‐term abstinence).

Non‐tailored materials and advice versus advice alone

Eleven studies with a total of over 5000 participants tested self‐help materials as an adjunct to face‐to‐face advice from a healthcare provider. We noted little heterogeneity and found no evidence that the additional self‐help materials significantly increased quit rates (n = 5365; RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.28; I² = 32%; Analysis 1.4). Whether or not the control group received materials did not affect the estimate. Control group quit rates ranged from 2% to 25% with an average of 7%. As would be expected, this is higher than the rates seen in control groups that received no intervention.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Non‐tailored self‐help vs no self‐help, pooled by amount of contact, Outcome 4 Both groups had face‐to‐face contact with advice (long‐term abstinence).

Overall effect of non‐tailored self‐help, alone or as adjunct to advice

When we pooled 32 studies of self‐help materials compared to no self‐help, irrespective of the level of contact and support common to the control group, the point estimate showed a small benefit of the intervention but the confidence interval included the possibility of no difference (n = 28,451; RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.19; I² = 25%; Analysis 2.1;Figure 3). (Note: the estimate excludes Becona 2001a, Becona 2001b, and Fraser 2014. Betson 1998 contributes data to two subgroups.)

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Self‐help vs no self‐help, pooling all studies, outcome: 2.1 Long‐term abstinence.

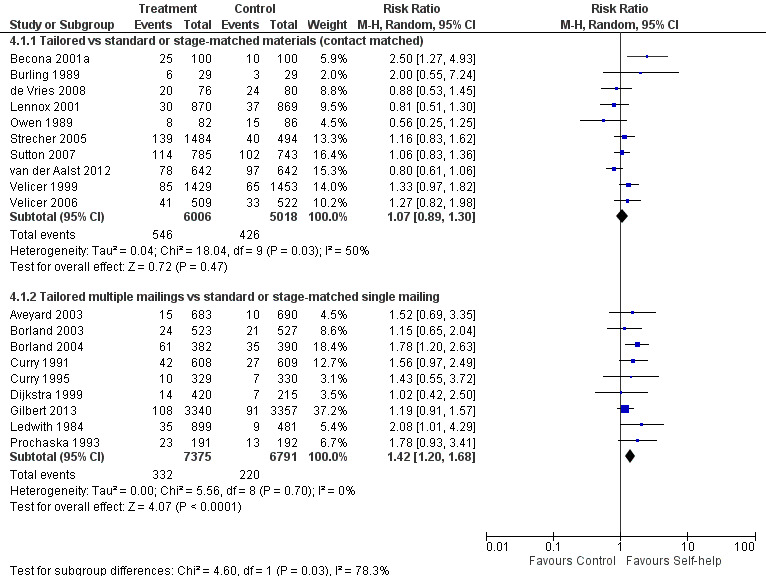

Tailored self‐help materials (Comparisons 3 and 4)

Participants in 10 studies receiving tailored self‐help materials had higher quit rates than those receiving no materials at all (n = 14,359; RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.51; I² = 0%; Analysis 3.1.1). Control group quit rates were 4% to 7%. Estimates were largely based on sustained but self‐reported abstinence, with the exception of Prochaska 2005, which reported only point prevalence quit rates. In two studies comparing tailored materials with brief advice (n = 2992), the risk ratio favoured the self‐help intervention but confidence intervals were wide (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.49; I² = 0%; Analysis 3.1.2). In the two studies evaluating tailored self‐help as an adjunct to brief advice, the risk ratio favoured the self‐help intervention, and confidence intervals excluded no effect (n = 1839; RR 1.72, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.53; I² = 10%; Analysis 3.1.3). When we pooled these three groups of studies comparing tailored self‐help materials with no self‐help, the overall result favoured self‐help interventions with confidence intervals excluding no effect (n = 19,190; RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.49; I² = 0%).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Tailored self‐help vs no self‐help, Outcome 1 Long‐term abstinence.

In other studies of tailored materials, the control groups received standard self‐help materials. Ten studies that matched intervention and control groups for number of contacts did not detect a benefit (n = 11,024; RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.30; I² = 50%; Analysis 4.1.1; Figure 4). We noted some evidence of heterogeneity (I² = 50%), largely contributed by Becona 2001a where there was a significant effect of weekly feedback reports. Sutton 2007 included some recent quitters for whom the effect of intervention was smaller, but restricting inclusion to those still smoking at enrolment had little impact on the pooled estimate. Velicer 1999 showed an almost significant effect based on numbers randomised. Excluding dropouts from the denominators increased the estimated effect a little because more people were lost from the expert system intervention groups. This study also tested different numbers of tailored versus non‐tailored mailings but did not detect a consistent dose‐response effect (data not reported).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Tailored self‐help vs non‐tailored self‐help, Outcome 1 Long‐term abstinence.

4.

Tailored self‐help materials: Long‐term abstinence.

Nine studies that compared tailored materials with a non‐tailored control and in which the tailored arms received multiple contacts and the non‐tailored arms received a single contact found consistent results in favour of multiple tailored materials. Although none of these studies individually had statistically significant results, the pooled estimate suggests benefit of the intervention (n = 14,166; RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.68; I² = 0%; Analysis 4.1.2; Figure 4).

Webb 2013 detected a benefit of 'placebo tailoring' (n = 424; RR 1.98, 95% CI 1.18 to 3.31; analysis not shown), suggesting that the actual content of the tailored message may be less important than the perception that it is individualised.

Self‐help materials plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) compared to NRT alone (Comparison 5)

Studies that specifically examined self‐help materials in addition to NRT did not show any evidence of additional benefit from these materials over the relatively high quit rates achieved with use of NRT (n = 1769; RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.30; I² = 0%; Analysis 5.1). The control group quit rate was over 20% in two of the three studies. Results show no difference between the two studies using standard materials and the two using tailored materials. Due to insufficient data, we were unable to include another relevant study in this analysis (Fraser 2014); however, this study also did not detect a statistically significant benefit of standard self‐help as an adjunct to NRT.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Self‐help plus NRT vs NRT alone, Outcome 1 Long‐term abstinence.

Other enhancements or adjuncts to self‐help materials (Comparison 6)

Additional written materials

Pooled results from four studies of additional written materials favoured the intervention, but the lower confidence interval crossed the line of no effect and there was substantial heterogeneity (RR 1.20, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.58; I² = 73%; Analysis 6.1.1). We compared the two arms of Brandon 2016 with control separately in the meta‐analysis. However, when compared with each other the results favoured the standard mailings arm over the intensive mailings arm (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.47). Cuckle 1984 did not send further materials until six months after sending the initial 'quit kit', but excluding this study does not affect the estimate. We excluded one previously included study from this update because the intervention was given for relapse prevention (Killen 1990). Another Cochrane Review included this study (Hajek 2013).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Other enhancements/adjuncts to self‐help materials, Outcome 1 Long‐term abstinence.

Additional video

Killen 1997 used a video as an adjunct to written materials and did not detect a significant overall benefit (n = 424; RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.51; I² = 38%; Analysis 6.1.2). There was a non‐significantly lower quit rate in the active nicotine patch group amongst those who received the video as well as written materials.

Materials targeted at particular populations of smokers

Five studies of materials targeted at specific populations failed to show evidence of significant benefit compared to standard materials (n = 3101; RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.38; I² = 0%; Analysis 6.1.3). Two studies provided telephone counselling to callers to quitlines before sending them materials (Davis 1992; Orleans 1998 (in which the counselling was also tailored)), and Nollen 2007 provided all participants with nicotine replacement therapy. These common components may have contributed to the success in quitting among all groups and limited the potential to detect effects of small differences in adjunct materials.

Comparisons between different types of self‐help material

We did not perform meta‐analysis of this heterogeneous group of studies. Glasgow 1981 (n = 88) compared two different manuals and found no evidence of a difference because of very wide confidence intervals (RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.13 to 67.51). Omenn 1988 (n = 243) compared a multiple‐component manual with a quitters' guide and starter programme, finding no evidence of difference in quit rates (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.46 to 3.71). ICRF 1994 (n = 1686) also found no significant difference in outcome between those given a longer or a shorter booklet in conjunction with either a nicotine or placebo patch and nurse support (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.81, 1.27). Berman 1995 compared two types of materials for 348 smoking participants volunteering for heart health screening and cessation. There was no significant difference in quit rates (RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.43). Clark 2004 (n = 171) did not detect the hypothesised benefit of a list of internet resources over standard material. These results favoured the standard materials but with wide confidence intervals (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.40). Becona 2001b (n = 482) compared weekly mailings with a single manual and detected no significant difference (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.19). Smith 2004 (n = 632) compared a 44‐page booklet with a pamphlet when used as adjuncts for motivated quitters receiving an extended telephone counselling session and one of two intensities of follow‐up counselling. The effect estimate favoured the longer booklet but the confidence intervals were wide, including the line of no effect (RR 3.26, 95% CI 0.98 to 10.85). Sykes 2001 (n = 260) showed a statistically significant effect after six months with a more than three‐fold increase in the chance of quitting when comparing a cognitive‐behavioural self‐help programme with a standard leaflet, with both used as an adjunct to a single introductory session in a group format (RR 3.45, 95% CI 1.44 to 8.26). This finding was sustained at 12 months' follow‐up (Marks 2002; RR 3.77, 95% CI 1.59 to 8.96).

Discussion

Summary of main results

We defined 'self‐help materials' as those providing a structured approach to smoking cessation. Using this definition, we found moderate evidence that such materials, used on their own and compared with no intervention, marginally but significantly increased the number of people able to quit smoking (Table 1). The point estimate was higher for tailored materials than for non‐tailored materials, but we found no significant differences between studies comparing tailored and non‐tailored materials directly. For non‐tailored materials, the certainty of the result was moderate because whilst the intervention was compared with a no‐intervention control, the evidence came from studies conducted in high‐income countries, where more intensive forms of support are readily available. For tailored materials, where the confidence intervals did exclude the possibility of no effect, certainty was moderate due to risk of bias in the included studies.

Providing non‐tailored self‐help materials in addition to advice from a healthcare professional did not improve the outcome. However, tailored self‐help as an adjunct to brief advice did provide additional benefit, but this comparison included only two studies. We found little evidence of an effect of self‐help materials given in addition to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Self‐help programmes provide information on how to quit smoking but do not provide the sense of being supported nor the interactive elements of more sophisticated behavioural programmes. In many high‐income countries, people know how to quit smoking or can find advice easily; therefore, in these contexts, it is possible that self‐help interventions are less effective than might be the case where such information is not generally known or easily available. The studies included in this review overwhelmingly represent populations with this knowledge and with access to more intensive stop‐smoking support (of the 75 included studies, 74 were conducted in high‐income countries according to the World Bank definition; the one outlier was conducted in Hong Kong). This review, therefore, can inform decisions as to whether print‐based self‐help should be used in developed countries, but paradoxically it cannot tell us about the population that these interventions are now most likely to benefit ‐ people who do not have other support available. By the 2020s or early 2030s, the World Health Organization estimates that more than 7 million tobacco‐related deaths will occur in low‐ and middle‐income countries each year. In light of this, even a very modest effect size could have significant public health impact when applied at a population level. Further research conducted outside of high‐income countries is therefore needed to determine whether print‐based self‐help interventions still have a role to play. Without this, the evidence is incomplete and may not be applicable to the most relevant population.

There is also the potential for ambiguity in the inclusion criteria for this review, as studies do not always report in detail the nature of print‐based interventions, and some interventions may be borderline between print‐based self‐help and printed materials that simply provide information. As such, we may have excluded some studies in which the print‐based intervention did constitute a self‐help intervention as defined in this review on the grounds that it is not clear from the report that the printed materials constituted a structured programme for people to follow to quit smoking. However, whilst there is a risk that we may not have included some eligible studies, we have no reason to suspect that this should result in systematic bias.

Although our searches included clinical trials registries and other sources of unpublished data, we cannot rule out the risk of publication bias. However, we prepared funnel plots for all comparisons with at least 10 studies, and none provided evidence of asymmetry.

Certainty of the evidence

We judged the evidence for our main comparisons to be of moderate certainty in accordance with GRADE. We downgraded the evidence for standard self‐help programmes for being indirectly relevant to populations in low‐ and middle‐income countries because evidence for this comparison came from studies conducted solely in high‐income countries and because of differences between higher‐ and lower‐income countries in literacy rates, availability of support, and prevalence of stop‐smoking messages, there is reason to believe the intervention might work differently. We downgraded the evidence for tailored self‐help materials because of risk of bias. Many study reports did not provide sufficient detail for judgement of risk of bias for some domains. Of the 75 included studies, we judged 30 of them (40%) to be at high risk of bias for one or more domains.

Potential biases in the review process

Our conclusions about the effects of self‐help materials are based on an intention‐to‐treat analysis in which we included all randomised participants, whether or not they received the intended intervention. We also made the assumption that all participants who could not be reached for follow‐up or who declined further participation were still smoking. It has been argued that in minimal contact population‐based studies, participants may be unreachable for reasons unrelated to their smoking status, and that the assumption that they are all smokers leads to unnecessarily conservative quit rates (Hall 2001; Prochaska 2001a). Prochaska, Velicer, and colleagues distinguish between those lost to follow‐up and those who withdraw from the study. We have used numbers randomised in our primary analysis, but we conducted a sensitivity analysis of the effect of using numbers followed up as the denominator. This of course increases the average quit rates in both intervention and control groups, but because dropout rates are typically quite similar across study arms, this has only a small impact on the estimate of relative effect. It has no effect on our conclusions about tailoring.

One reason that it may be difficult to show efficacy for standard self‐help programmes is the level of 'contamination'. Materials encouraging smokers to quit and giving tips are already relatively widely disseminated, so that smokers in a control arm who are motivated to try to give up may well have access to the same kinds of materials that experimental arm smokers have been given. On the other hand, there may be more fundamental reasons why behavioural interventions are more effective when delivered by face‐to‐face contact. Killen has suggested, for example, that the self‐regulatory skills required to withstand the urge to smoke may be better learnt, rehearsed, and retained under the direct supervision of a therapist than through the simple modelling offered by self‐help materials (Killen 1997). Strecher has suggested that the length of generic self‐help manuals and pamphlets may discourage effective use of these materials (Strecher 1994). Meade 1989 suggested that self‐help materials may be too advanced for many readers, and that comprehension can be improved by adjustment of the reading grade level. Tailored materials may have the potential to address these issues.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review found a small effect in favour of print‐based self‐help compared with no intervention (risk ratio (RR) 1.19, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03 to 1.37; I² = 0%). This effect is less pronounced than that found in the Cochrane Review of mobile‐based interventions (Taylor 2017; RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.46 to 1.90; I² = 59%), and it is more pronounced than that found in the Cochrane Review of internet‐based interventions (Whittaker 2016; RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.09; I² = 0%). However, the results of the internet‐based interventions review were based on a comparison with an active control rather than no treatment.

Our review favoured tailored self‐help over no materials (RR 1.34, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.51; I² = 0%). When comparing tailored self‐help to non‐tailored self‐help, results favoured tailored interventions when the tailored interventions contained more mailings than the non‐tailored interventions (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.68; I² = 0%), but not when the two conditions were contact matched (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.30; I² = 50%). The Cochrane Review of internet‐based interventions favoured interactive and tailored interventions over non‐active control (RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.30) and favoured an interactive or tailored programme over a non‐tailored internet intervention, but the estimate crossed the null (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.22; I² = 0%). The review did not comment on any differences in contact between groups, but it is unlikely that contact differed because of the online nature of the interventions. Given the difficulty of obtaining baseline data and the delays involved in mailing printed materials, newer formats for providing self‐help support may have greater potential for providing relevant and timely interventions. Although the evidence from studies is not yet optimal, using the internet to provide individually tailored information and support appears promising and may avoid the limitations of printed self‐help materials. Using mobile phones to deliver text message‐based interventions also shows promise for supporting people who are making quit attempts.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Structured self‐help programmes provided in short booklets increase the likelihood of a person stopping smoking successfully in the medium to long term. However, there is no evidence that they add to the effectiveness of brief advice or pharmacological interventions.

Print‐based self‐help that is tailored to the characteristics of individual smokers may be more helpful. However, more modern formats for providing tailored self‐help support, such as the internet and mobile phones, may have greater potential because of advantages in gathering information to tailor by and in delivering support more quickly and flexibly.

Implications for research.

Almost all included studies were conducted in high‐income countries with well‐developed tobacco control policies and high literacy rates. The effect of this climate on the intervention effectiveness is unclear. In low‐ and middle‐income countries, tobacco control policies are often less developed and literacy rates may be lower than in high‐income countries. Future research in low‐ and middle‐ income countries would be useful because the intervention is potentially more cost‐effective than other cessation aids, but the impact of print‐based self‐help interventions in such a context remains unclear.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 January 2019 | Amended | Minor change to phrasing of abstract |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1998 Review first published: Issue 4, 1998

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 September 2018 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions unchanged |

| 5 September 2018 | New search has been performed | Search updated to March 2018. Three new studies included |

| 7 May 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | JH‐B added as author. Review title changed from "Self‐help interventions for smoking cessation" |

| 7 May 2014 | New search has been performed | Updated with 6 new studies. 'Summary of findings' table added. Risk of bias domains added |

| 28 January 2009 | New search has been performed | Updated with 10 new studies for Issue 2, 2009. No major changes to results |

| 29 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format |

| 28 April 2005 | New citation required and minor changes | Updated for Issue 3, 2005, with 9 new studies. Most studies used tailored interventions and strengthened the evidence that tailored materials are more useful than standard ones |

| 10 April 2002 | New citation required and minor changes | Updated for Issue 3, 2002, with 10 new studies. Most studies used tailored interventions and strengthened the evidence that tailored materials are more useful than standard ones |

| 13 October 1999 | New search has been performed | Updated for Issue 1, 2000, with 4 new trials |

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Sue Curry, Paul McDonald, and Saul Shiffman for their comments, and to Ann Varady, Joe Rossi, Christine Edwards, Neal Boyd, Virginia Rice, and Tracy Orleans for providing additional data from published or unpublished studies. Our thanks also to Timothy Lancaster and Lindsay Stead, who were the authors of previous versions of this review, and Sandra Wilcox and Lee Bromhead, who reviewed the plain language summary.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), via Cochrane Infrastructure and Cochrane Programme Grant funding to the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health and Social Care. JHB is also funded in part by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Appendices

Appendix 1. CRS search strategy

#1 (self‐help OR selfhelp OR manual* OR booklet* OR pamphlet*):TI,AB,MH,EMT,KW,KY,XKY #2 (leaflet* or letter* or video*):TI,AB,MH,EMT,KW,KY,XKY #3 #1 OR #2

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Non‐tailored self‐help vs no self‐help, pooled by amount of contact.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Neither group had face‐to‐face contact (long‐term abstinence) | 17 | 20264 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.92, 1.20] |

| 1.1 Control group given no materials | 11 | 13241 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [1.03, 1.37] |

| 1.2 Control group given leaflet/pamphlet | 6 | 7023 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.71, 1.07] |

| 2 Neither group had face‐to‐face contact (Becona studies only) | 2 | 924 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 10.91 [5.03, 23.66] |

| 2.1 Control group given no materials | 2 | 924 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 10.91 [5.03, 23.66] |

| 3 Both groups had face‐to‐face contact (long‐term abstinence) | 4 | 2822 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [1.03, 1.88] |

| 3.1 Control group given no materials | 3 | 1668 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.80, 2.26] |

| 3.2 Control group given leaflet/pamphlet | 1 | 1154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.98, 2.04] |

| 4 Both groups had face‐to‐face contact with advice (long‐term abstinence) | 11 | 5365 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.76, 1.28] |

| 4.1 Control group given no materials | 8 | 3581 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.66, 1.27] |

| 4.2 Control group given leaflet/pamphlet | 3 | 1784 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.71, 1.95] |

Comparison 2. Non‐tailored self‐help vs no self‐help, pooling all studies.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Long‐term abstinence | 31 | 28451 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.95, 1.19] |

| 1.1 No contact/No materials for control | 11 | 13241 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [1.03, 1.37] |

| 1.2 No contact/Leaflet for control | 6 | 7023 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.71, 1.07] |

| 1.3 Face‐to‐face contact/No materials for control | 3 | 1668 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.80, 2.26] |

| 1.4 Face‐to‐face contact/Leaflet for control | 1 | 1154 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.98, 2.04] |

| 1.5 Advice/No materials for control | 8 | 3581 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.66, 1.27] |

| 1.6 Advice/Leaflet for control | 3 | 1784 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.71, 1.95] |

Comparison 3. Tailored self‐help vs no self‐help.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Long‐term abstinence | 12 | 19190 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.34 [1.20, 1.49] |

| 1.1 Tailored materials vs no materials | 10 | 14359 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.34 [1.19, 1.51] |

| 1.2 Tailored materials vs brief advice | 2 | 2992 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.86, 1.49] |

| 1.3 Tailored materials as an adjunct to advice | 2 | 1839 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.72 [1.17, 2.53] |

Comparison 4. Tailored self‐help vs non‐tailored self‐help.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Long‐term abstinence | 19 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |