Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a recently discovered viral disease, characterized by fever, cough, acute fibrinous pneumonia and high infectivity. Specific pathogen-free (SPF) chickens were immunized with inactivated SARS coronavirus and their eggs were harvested at regular intervals. Yolk immunoglobulin (IgY) was extracted using the water dilution method, followed by further purification on a Sephadex G-75 column. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), Western blot and neutralization test results showed that the IgY obtained was of a high purity and had a strong reactive activity with a neutralization titer of 1:640. Lyophilization and stability tests showed that lyophilized anti-SARS coronavirus IgY had promising physical properties, with no significant reduction in reactive activity and good thermal stability. All these data suggest that the anti-SARS coronavirus IgY could be a new useful biological product for specific antiviral therapy against SARS.

Keywords: IgY, Severe acute respiratory syndrome virus, SARS, Neutralization activity

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a recently discovered viral disease, characterized by fever, cough, acute fibrinous pneumonia and high infectivity (Chang, 2005). Outbreaks of SARS during 2003 caused concern around the world as a serious health threat. Comprehensive prevention and treatment measures were taken internationally, while at the same time research on the SARS coronavirus and development of a vaccine, therapeutic drugs and biological products was commenced immediately. Research has been successful and considerable progress has been made in all of these fields (Chow et al., 2003).

Analyses of nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the SARS coronavirus demonstrated that it did not belong to any of the three known subgroups of coronaviruses and therefore was identified as a new kind of coronavirus (Wang and Ding, 2003). Recent progress has been made in production of biological products against SARS. As high-titer human antiserum against SARS coronavirus has been found to be capable of inhibiting the multiplication of the SARS virus, the prospect of confirming passive immunity against SARS for infected patients and for non-infected individuals at risk is feasible.

Passive immunization and short-term protection with high antibody titers has historically been an effective way to combat fulminating infectious disease. During the outbreak of SARS in China in 2003, some positive results were achieved by passive immunization when the sera of recovered SARS patients were used. No adverse reactions were observed in the first vaccinated volunteers. In order to provide new and effective passive immunization against SARS, basic studies on the SARS coronavirus antibody should be carried out. These studies should include searching for better antibody sources, increasing output and improving techniques of production and purification. In this study, we have successfully immunized specific pathogen-free (SPF) chickens, and then purified a high-titer anti-SARS coronavirus yolk immunoglobulin (IgY) with neutralizing activity against SARS coronavirus.

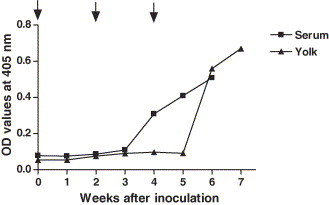

SARS coronavirus antigen was prepared using SARS virus strain BJ01 and kindly provided by the Chinese Academy of Military Medical Sciences, Beijing, China. The virus culture was inactivated by β-propiolactone and purified on a sucrose gradient centrifugation as described previously (Yin and Liu, 1997). Thirty 17-week-old SPF Leghorn hens were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of the Harbin Veterinary Research Institute, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Harbin, China. Chickens were immunized by injecting 0.18 mg of SARS coronavirus antigen into the pectoral muscle. The second and third booster injections of 0.30 mg antigen were administered 2 and 4 weeks later. Blood was harvested before and after each immunization and eggs were harvested when they became available. The isolation of IgY from individual eggs was performed using the protocol described by Akita and Nakai (1993). Briefly, the egg white was separated from the egg yolk and discarded. The yolk was mixed vigorously with sterilized water and left standing overnight at 4 °C. The mixture was then centrifuged at 1200 × g at 4 °C for 30 min, and the supernatant was purified by chromatography The protein concentration in harvested eluate was measured by thin-layer gel scan. The recovery rate of crude protein before chromatography was found to be 56% while the purity was 92% after chromatography. The eluate was subjected to analysis by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot. The isolated IgY had a high purity as confirmed by SDS-PAGE and purified IgY had good biological activity as confirmed by Western blot. The activity of IgY in sera and yolks diluted at 1:200 in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) from immunized animals was assessed using an indirect ELISA assay as described previously (Huang et al., 2005) (Fig. 1 ). After immunization of SPF chickens with SARS coronavirus antigen, there were no detectable antibodies against SARS coronavirus in the yolks of eggs laid in the first 3 weeks after the first immunization. The production of anti-SARSV antibody in yolks was found to commence 2 weeks after the IgY was produced in serum.

Fig. 1.

Patterns of SARS coronavirus antibodies from sera and yolks of immunized SPF chickens. The arrows indicate the immunization times.

An IgY-neutralizing virus assay was performed in laminar-flow safety cabinets. Briefly, serially diluted samples of the IgY were incubated with 200 TCID50 of SARS coronavirus at 37 °C for 1 h, then inoculated onto VERO E6 cells and incubated at 37 °C in a CO2 incubator. Uninfected VERO E6 cells and SARS-positive serum or SPF chicken serum were used as controls for this experiment. The IgY did not react with Vero cells when tested by indirect fluorescent antibody technique. Infectivity titers were calculated using a standard TCID50 assay. The highest antibody dilution that inhibited cytopathic effect in 50% of the VERO E6 cells inoculated with this dilution was regarded as the 50% neutralization titer. The results of neutralization experiments (Table 1 ) indicated that yolk antibody till 1:640 dilution was effective in neutralizing the SARS coronavirus, and were consistent with the ELISA result when extracted yolk antibody was used.

Table 1.

Results of neutralization test and ELISA of extracted anti-SARS coronavirus IgY

| IgY dilution | 1:2560 | 1:1280 | 1:640 | 1:320 | 1:160 | 1:50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutralization titer | 0 | 0 | 1:640 | 1:320 | 1:160 | 1:50 |

| ELISA OD values at 405 nm | 0.376 | 0.381 | 0.581 | 0.475 | 0.441 | 0.494 |

For the lyophilization procedure, yolk was isolated and mixed with phosphate buffer saline at a ratio of 1:9 (v/v), followed by centrifugation and degreasing. Aliquots were loaded into 4-ml bottles to which less than 0.01% (g/ml) merthiolate was added. Each bottle was vacuumed and lyophilized according to standard methods. The samples were tested for antibody titers before and after lyophilization. IgY after drying showed good physical properties including pale yellow color. The binding activity of IgY in ELISA did not change significantly after lyophilization (Table 2 ). Stability testing of lyophilized IgY demonstrated that IgY binding did not decrease significantly until the temperature reached 90 °C for 15 min in hot water (Table 3 ), indicating the IgY had good heat stability. There was no change in IgY activity under acid conditions from pH 7 to 2 after treatment at 37 °C for 2 h (Table 4 ). Furthermore, binding activity of lyophilized IgY did not change after 5-month storage at either −20, 4 °C or room temperature (Table 5 ).

Table 2.

Effect of lyophilization on extracted anti-SARS coronavirus IgY

| Dilution |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:4 | 1:50 | 1:100 | 1:200 | 1:400 | 1:800 | 1:1600 | 1:3200 | 1:6400 | 1:12800 | 1:25600 | 1:51200 | |

| ELISA OD values at 405 nm | ||||||||||||

| Before lyophilization | 0.319 | 0.370 | 0.374 | 0.378 | 0.390 | 0.392 | 0.385 | 0.383 | 0.339 | 0.282 | 0.217 | 0.152 |

| After lyophilization | 0.320 | 0.379 | 0.366 | 0.360 | 0.360 | 0.344 | 0.352 | 0.345 | 0.324 | 0.270 | 0.204 | 0.158 |

Table 3.

Test of thermal stability of lyophilized IgY

| Temperature (°C) for 15-min treatment |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 37 | 45 | 56 | 65 | 70 | 80 | 90 | |

| ELISA OD values before lyophilization | 0.520 | 0.471 | 0.496 | 0.632 | 0.489 | 0.459 | 0.483 | 0.069 |

| ELISA OD values after lyophilization | 0.470 | 0.590 | 0.470 | 0.464 | 0.501 | 0.437 | 0.427 | 0.073 |

Table 4.

Acid resistance of lyophilized anti-SARS coronavirus IgY

| pH |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

| ELISA OD values before lyophilization | 0.301 | 0.350 | 0.385 | 0.431 | 0.394 | 0.396 |

| ELISA OD values after lyophilization | 0.335 | 0.360 | 0.372 | 0.440 | 0.382 | 0.345 |

Table 5.

Temperature sensitivity test of lyophilized anti-SARS coronavirus IgY

| ELISA OD values at 405 nm |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month | 2 months | 3 months | 4 months | 5 months | |

| −20 °C | 0.397 | 0.347 | 0.355 | 0.194 | 0.222 |

| 4 °C | 0.393 | 0.359 | 0.371 | 0.195 | 0.227 |

| Room temperature | 0.383 | 0.369 | 0.373 | 0.230 | 0.228 |

| Negative control | 0.068 | 0.067 | 0.069 | 0.062 | 0.062 |

| SARS-positive seruma | 0.375 | 0.300 | 0.354 | 0.302 | 0.207 |

| SPF chicken serum | 0.090 | 0.082 | 0.080 | 0.094 | 0.090 |

The SARS-positive serum was from the diagnostic kit provided by the Chinese Academy of Military Medical Sciences.

IgY from SPF chickens provides a rich source of antibody that is easy to obtain and is cost effective. The advantages of SPF chicken IgY over antibodies from other mammals include a high concentration and freedom from specific pathogens, making the use of IgY a broader prospect for development (Schade et al., 1992, Tini et al., 2002). The IgY from SPF chickens in our study maintained good biological and neutralization activity at environmental conditions. The recovery rate after purification by water dilution and the level of purity after further purification were promising, the binding of IgY remained unchanged after lyophilization, also making it feasible for the product that had been prepared in this way to be used for passive immunization and short-term protection.

Since the first outbreak of SARS transmission of the virus has been controlled and the potential for an epidemic has been alleviated by isolation of suspected patients in combination with drug therapy, based on clinical and epidemiological characteristics of SARS. Long-term control of SARS, however, will require a combination of active and passive immunizations, drug therapy and other comprehensive measures. It is therefore of vital importance to be able to produce vaccines and passive immunization products for effective control of SARS. The development of high-titer anti-SARS coronavirus IgY described in this study would appear to have potential as a new anti-SARS biological product for passive immunization, as it effectively neutralized the SARS coronavirus. In the present study, anti-SARS IgY was already prepared as a crude and purified product, while an indirect ELISA test was used for quality control of IgY production. To facilitate the process of mass production of purified IgY, the techniques of degreasing and purification would be key points for further study. After evaluation using experimentally infected animal models, anti-SARS IgY produced in this study has the potential to be commercially manufactured. The efficency of capsules produced from crude IgY or spray powder and intravenous solution manufactured from more highly refined IgY will need to be determined as the next step in development of IgY products.

Acknowledgments

We thank Simon Fenton and Trevor Bagust (Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Melbourne) and Cui Xianlan (Landcare Research New Zealand) for their critical reading and comments to assist the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Akita E.M., Nakai S. Comparison of four purification methods for the production of immunoglobulins from eggs laid by hens immunized with an enterotoxigenic E. coli 2 strain. J. Immunol. Methods. 1993;160:207–214. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90179-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S.C. Clinical findings, treatment and prognosis in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Chin. Med. Assoc. 2005;68:106–107. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70229-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow K.Y., Hon C.C., Hui R.K., Wong R.T., Yip C.W., Zeng K., Leung E.C. Molecular advances in severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) Genomics Proteomics Bioinf. 2003;1:247–262. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(03)01031-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Fu C., Wang Z., Cui S., Gao H., Wang X., Li Z., Li J., Kong X. Establishment of the detection method of anti SARS yolk antibody and serum antibody. Heilongjiang Ani. Sci. Vet. Med. 2005;282:51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Schade R., Schniering A., Hlinak A. Polyclonal avian antibodies extracted from egg yolk as an alternative to the production of antibodies in mammals—a review. ALTEX. 1992;9:43–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tini M., Jewell U.R., Camenisch G., Chilov D., Gassmann M. Generation and application of chicken egg-yolk antibodies. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2002;131:569–574. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Ding Q. SARS coronaviruses. Chin. Virol. 2003;18:303–306. [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z., Liu J. second ed. Science Press; Beijing: 1997. Animal Virology. pp. 303–323. [Google Scholar]