Abstract

It is believed today that nucleocapsid protein (N) of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV is one of the most promising antigen candidates for vaccine design. In this study, three fragments [N1 (residues: 1–422); N2 (residues: 1–109); N3 (residues: 110–422)] of N protein of SARS-CoV were expressed in Escherichia coli and analyzed by pooled sera of convalescence phase of SARS patients. Three gene fragments [N1 (1–1269 nt), N2 (1–327 nt) and N3 (328–1269 nt)—expressing the same proteins of N1, N2 and N3, respectively] of SARS-N were cloned into pVAX-1 and used to immunize BALB/c mice by electroporation. Humoral (by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, ELISA) and cellular (by cell proliferation and CD4+:CD8+ assay) immunity was detected by using recombinant N1 and N3 specific antigen. Results showed that N1 and N3 fragments of N protein expressed by E. coli were able to react with sera of SARS patients but N2 could not. Specific humoral and cellular immunity in mice could be induced significantly by inoculating SARS-CoV N1 and N3 DNA vaccine. In addition, the immune response levels in N3 were significantly higher for antibody responses (IgG and IgG1 but not IgG2a) and cell proliferation but not in CD4+:CD8+ assay compared to N1 vaccine. The identification of antigenic N protein fragments has implications to provide basic information for the design of DNA vaccine against SARS-CoV. The present results not only suggest that DNA immunization with pVax-N3 could be used as potential DNA vaccination approaches to induce antibody in BALB/c mice, but also illustrates that gene immunization with these SARS DNA vaccines can generate different immune responses.

Keywords: SARS-CoV, DNA immunization, Nucleocapsid, Epitope

1. Introduction

A life-threatening and highly emerging disease called severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) originated in China in late 2002 and spread rapidly to many countries. Upon this outbreak, a worldwide collaboration network was coordinated by WHO. As a result of this extraordinary endeavor, in March 2003, SARS-CoV, a novel type of coronavirus, was identified as the etiologic agent of SARS [1]. The genomic sequence of SARS-CoV was completed and it was found that SARS-CoV has all the features and characteristics of other coronaviruses (groups I–III), but it is quite unique from them, representing a new group (group IV) [2], [3]. SARS-CoV is believed to be a mutant coronavirus transmitted from a wild animal that developed the ability to productively infect humans [2], [4].

Till date, there is no operational treatment for SARS. Quarantine or transmission-blocking measures have been the only means existing to curb its ruinous impact. Individuals convalescing from SARS have been seen to develop high titres of neutralizing antibodies [5]. Moreover, the appearance of antibodies coincides with the onset of SARS pneumonia [6], [7]. These reports point to the possibility of vaccination as an effective therapy against SARS-CoV.

Prevention through vaccination would be a promising option that is less reliant on individual case detection to be effective. Even though there are no vaccines currently licensed for the human CoVs, vaccines have been successfully produced for some animal CoVs, such as certain strains of infectious bronchitis virus (poultry), bovine coronavirus and canine coronavirus [8], [9], [10], [11], [12].

The genome of SARS-CoV is a single-stranded plus-sense RNA ∼30 kb in length and contains five major open reading frames (ORFs) that encode non-structural replicase polyproteins and structural proteins: the spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M) and nucleocapsid protein (N), in the same order and of approximately the same sizes as those of other coronaviruses [2], [4].

The SARS-CoV nucleocapsid (N) gene encodes a 50-kDa protein harbouring a putative nuclear localization signal [2]. However, the N protein is distributed predominantly in the cytoplasm of SARS-CoV-infected and N gene-transfected cells [13]. The SARS-CoV N protein is a highly charged, basic protein that can self-associate to form dimmers [14]. The three-dimensional structure of the N-terminal portion of the protein shares similarity with that of other RNA-binding proteins. The coronavirus N protein is thought to participate in the replication and transcription of viral RNA and to interfere with cell-cycle processes of host cells. As a result, it plays a critical role in SARS CoV pathogenesis [14], [15], [16], [17]. In addition, the N proteins of many coronaviruses are highly immunogenic and expressed abundantly (90%) during infection [18]. High levels of IgG antibodies against N have been detected in sera from SARS patients [19]. The N protein can induce protective immunity or at least set up the protective response in some coronaviruses [20]. It is reported that N protein is a representative antigen for the T-cell response in vaccine setting [21], induces SARS-specific T-cell proliferation and cytotoxic T-cell activity and induces virus-specific cellular responses in human cells using mouse model [21], [22].

From such observations, we hypothesize that N protein expressed in viral infected cells may be an effective mediator of the potential target for SARS-CoV vaccine. To address this issue, we therefore focused our studies on characterization of the N protein [N1 (residues: 1–422 aa, full-length sequence protein); N2 (residues: 1–109 aa, N-terminal region) and N3 (residues: 110–422 aa, middle plus C terminal region)] of SARS-CoV as a target antigen for vaccine development.

We constructed eukaryotic expression plasmid encoding N [(N1 (nucleotide: 1–1269), N2 (nucleotide: 1–327), and N3 (nucleotide: 328–1296)) gene fragments of the SARS-CoV and compared their individual potential immune responses in BALB/c mice for use in the development of SARS vaccine candidates. Therefore, a safe and effective SARS vaccine would be highly beneficial to the human health system.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Molecular cloning, expression and purification of bacterium-derived SARS-CoV N protein

DNA fragments containing the full length and truncated SARS-CoV N gene were generated by PCR using SARS-CoV (strain Hanoi 01–03) cDNA as the template. Table 1 shows the forward and reverse primers with PCR cycling conditions that were used in order to sub-clone the PCR product as a Bam H1-Sal1 fragment into the pET21a vector (Novagen, Germany). Plasmids containing the N gene were then transformed into Escherichia coli strain Origami™ B (DE3). SARS-CoV N protein expression was induced in transformed competent cells by adding 1 mM IPTG (Invitrogen, USA) for 4 h. The expressed N protein, containing a small hexahistidine tag at the C terminus, was subsequently purified by using the His Bind® purification kits (Novagen) through Ni-IDA resin column and confirmed by SDS-PAGE using 12% polyacrylamide gels followed by western blotting using mouse anti-SARS N protein monoclonal antibody (1:1,000 dilution, Zymed, USA) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500 dilution, Zymed, USA) as a primary and secondary antibody, respectively. Purified proteins were then analyzed with pooled sera of convalescence phase of SARS patients as a positive control and healthy volunteers as a negative control.

Table 1.

Primer sequence, target site, restriction enzyme, product size and PCR conditions

| Expression | Target site | Sequence (5′–3′) | Restriction enzyme | Product size (bp) | PCR conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prokaryotic | N1 [1–1269] | F: CGG GGA TCC ATG TCT GAT AAT GGA CCC CAA | BamH1 | 1269 | 94 °C for 10 min, then 30 cycles of 94 °Cfor 30 s, 48 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C For 1 min, Followed By one cycle of 72 °C for 5 min |

| R: ACGC GTC GAC TGC CTG AGT TGA ATC AGC | Sal1 | ||||

| N2 [1–327] | F: CGG GGA TCC ATG TCT GAT AAT GGA CCC CAA | BamH1 | 327 | ||

| R: ACGC GTC GAC CCA TCT GGG GCT GAG CTC TTT | Sal1 | ||||

| N3 [328–1296] | F: CGG GGA TCC ATG TAC TTC TAT TAC CTA GGA ACT GGC | BamH1 | 942 | ||

| R: ACGC GTC GAC TGC CTG AGT TGA ATC AGC | Sal1 | ||||

| Eukaryotic | N1 [1–1269] | F: CGC GGA TCC ATG TCT GAT AAT GGA GCC CAA | BamH1 | 1269 | |

| R: CGG CTG CAG TTA TGC CTG AGT TGA ATC GC | Pst1 | ||||

| N2 [1–327] | F: CGC GGA TCC ATG TCT GAT AAT GGA GCC CAA | BamH1 | 327 | ||

| R: CTG CAG TCA CCA TCT GGG GCT GAG CTC TTT | Pst1 | ||||

| N3 [328–1296] | F: CGG GGA TCC ATG TAC TTC TAT TAC CTA GGA ACT GGC | BamH1 | 942 | ||

| R: CGG CTG CAG TTA TGC CTG AGT TGA ATC GC | Pst1 |

The underline sequences are restriction sites.

2.2. Plasmid DNA constructs and DNA preparation

In the present study, we used pVAX-1 (Invitrogen, USA), containing a CMV promoter and BGH polyadenylation sequence, for high-level mammalian expression of our DNA vaccine. For the generation of pVAX-N1/N2/N3, DNA fragments encoding SARS-CoV nucleocapsid were amplified by PCR using a set of primers as a template (Table 1). The amplified products were cloned into pGEM®-T Easy vector (Promega, UK). pGEMT-N genes were digested with Bam HI and PSTI (Roche, Switzerland) and then inserted into vector pVAX-1. The accuracy of these constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing (Genotech Company, Seoul, Korea). The sequences were identical to the reported sequence [Gene Bank accession number AY307165 (gi: 31540948)]. The DNA was amplified in E. coli DH5α strain and purified by plasmid-purification kit (Qiagen, USA) and dissolved in endotoxin-free PBS to a final concentration of 1 μg/μl, and stored at −20 °C. The 260/280 ratios ranged from 1.8 to 2.0. The endotoxin content from purified plasmid DNA was below 10 EU/ml in which the level had no effect on the immune response.

2.3. Transfection of 293T cells with pVAX-N and Western blot analysis

The human embryonic kidney cell line ATCC 293T (CRL 11268) was maintained in Dulbecco's modified eagle's medium (DMEM, Gibco BRL) supplemented with 0.1% penicillin–streptomycin–neomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2. When the cell density was 80–90% confluent, transfection was performed using a transfection kit (Trans IT-LT1 reagent, Myrus). Experimental groups were treated with the pVAX-N1/N2/N3 plasmid and a negative control was treated with pVAX1 plasmid. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were harvested and lysed using triple-detergent lysis buffer. The expressed proteins in the cells were separated on a 12% SDS polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (0.45 μm, Schleicher and Schuell GmbH, Dassel, Germany). The nitrocellulose membrane was incubated for 1 h with TNT [15 mmol/l Tris-base, 140 mmol/l NaCl, 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20] containing 5% (w/v) powdered skimmed milk. Membranes were probed with mouse anti-SARS nucleoprotein (Zymed Laboratories) at a 1:1000 dilution in T-PBS for 2 h, washed four times with T-PBS, and then incubated with peroxidase rabbit anti-mouse (CAPPEL) at a 1:500 dilution in T-PBS containing 5% non-fat milk. Membranes were washed four times with T-PBS and developed using Hyperfilm-enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.) [23].

2.4. Animals and immunizations

Eight-week-old female BALB/c mice, each weighing 18–20 g, free of adventitious rodent pathogens, ectoparasites and endoparasites, were used in this study. Mice were maintained in a certified animal house under supervision and standard conditions of 22 + 2 °C temperature and 55 + 10% relative humidity with a photoperiod of 12:12 h of light–darkness. Water and a dry pellet diet were given ad libitum. The mice were acclimatized for 4 days prior to the start of the experiments.

All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines [24] for the care and use of laboratory animals approved by Seoul National University [Approval number SNU070827-2].

Four groups (n = 5/group) of mice were used in this study: group 1 (negative control), group 2 (Sham control), groups 3 and 4 (experimental). Group 1 was immunized with 30 μl PBS, group 2 with 30 μg of pVAX-1, group 3 with 30 μg pVAX N1 and group 4 with 30 μg pVAX N3. All immunizations were carried out three times at 2-week intervals intramuscularly (i.m.) by electroporation in the right quadriceps muscle. Injections and electroporation treatments were made under light anesthesia induced by a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) into the tibialis anterior muscle. A pair of electrode needles with 5 mm between probes was inserted into the muscle to cover the DNA injection sites and electric pulses were delivered using an electric pulse generator (Electro Square Porator ECM 830; BTX, San Diego, USA). Four pulses of 100 V each were delivered to each injection site at the rate of one pulse per second, with each pulse lasting for 40 ms. This was followed by four pulses of the opposite polarity, as described previously [25].

2.5. Analysis of the humoral immune response

Serum antibodies against N1/N3 proteins were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Mouse sera (1:40) were collected the day before (day 0) and after 10 days of final immunization, for specific antibodies detection. N-specific immunoglobulin IgG and its subclasses (IgG1 and IgG2a) were assessed by ELISA. In this case, recombinant N (250 ng) protein expressed in E. coli was purified and used as the detection antigen. HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a (1:5000, Sigma) were used as secondary antibodies. Optical density (OD) was read at 490 nm (A 490) using a plate reader (Bio-Rad, USA). The values obtained for mouse sera from the experimental groups were considered positive when they were ≥2.1 times that of the control group. Values >0.05 were not included.

2.6. Measurement of lymphocyte proliferation index (LPI)

Antigen-specific T-cell proliferation assay (LPA) was performed as described [26]. In brief, 10 days following the final injection, mice were sacrificed and single-cell suspensions were prepared from the spleens for each group. Splenocytes (2 × 105/well) in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS were seeded in 96-well plates, in triplicates. Cultures were stimulated under the following various conditions for 60 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2: 5 μg/ml concanavalin A (positive control), 5 μg/ml purified N antigen (specific antigen), 5 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (irrelevant antigen), or medium alone (negative control). CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Reagent (20 μl, Promega, USA) was added into each well according to the manufacturer's protocols. Following 4 h incubation at 37 °C, absorbance was read at 490 nm. Proliferative activity was estimated using the stimulation index (SI) calculated from the mean OD490 of antigen-containing wells divided by the mean OD490 of wells without the antigen.

2.7. Analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes

Spleens of mice were excised and ground on a 200-mesh copper net. One hundred μl of a suspension containing 1 × 106 spleen cells were added into 5 ml PBS and centrifuged at 1500 × g for 5 min. After washing twice with PBS, the cells were re-suspended to make a 0.5-ml cell suspension. Twenty microliters of an anti-mouse CD8+ monoclonal antibody (mAb) labeled with FITC and a CD4+ mAb labeled with PE were added into the suspension. The cells were washed twice and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. Finally, 0.5 ml of fluorescence conservation solution was added, and the cells were then detected by a FACS Caliber flow cytometer and data were analyzed using the WinMDI software (Beckton Dickinson).

2.8. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Duncan's multiple range test (SAS v. 8.2, SAS Institute). p-Values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Production and identification of SARS-CoV N protein in E. coli

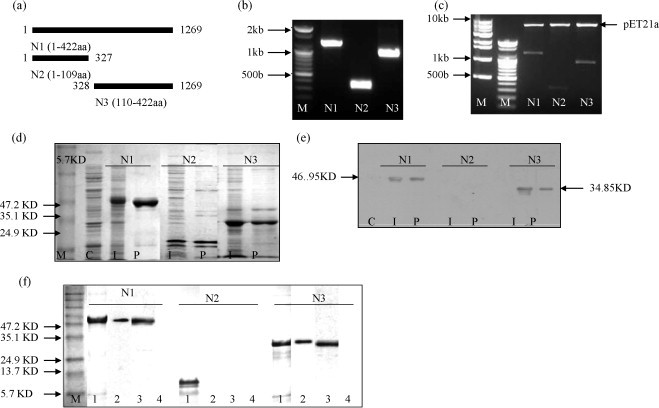

The full-length (N1) and truncated (N2 and N3) fragments of the N gene were cloned and expressed in E. coli Origami TM B (DE3) pLysS using expression plasmids, pET21a as described in Fig. 1c and Table 1. The inserts in plasmid were sequenced and proved to be correct. After induction with IPTG, the pET-N (pET-N1, pET-N2 and pET-N3) from E. coli with a hexahistidine tag were over-expressed, with expected sizes of 46.95, 12.09 and 34.85 kDa, respectively. pET-N1, N2 and N3 were successfully purified through resin based affinity chromatography (Fig. 1d). The truncated recombinant N1 and N3 (but not N2) proteins were identified by Western blotting with mouse SARS N protein antibody (Fig. 1e). We confirmed the same by using convalescent SARS patient sera as positive and healthy human sera as negative antibodies (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

Insert preparation, expression, purification and detection of N (N1/N2/N3) protein in E. coli Origami™ B (DE3). (a) Schematic representation of plasmid constructs expressing SARS-CoV N protein in prokaryotic expression vector and mammalian expression vector. Full-length N gene labeled as N1 (nucleotides: 1–1269) and truncated as N2 (nucleotides: 1–327) and N3 (nucleotides: 328–1296). The number is the amino acid position of N protein sequence. (b) PCR products of N1 (1269 bp), N2 (327 bp) and N3 (942 bp), M: DNA marker. (c) Prokaryotic expression vector (pET21a) cloning (BamH1 and Sal1 digestion). (d) Expression of N (N1/N2/N3) protein in E. coli by 12% SDS-PAGE. M: protein marker, C: control [protein from normal E. coli Origami ™ B (DE3)], I: 4 h after induction with 1 mM IPTG, P: N protein purification with His Band affinity Ni-IDA resin column. (e) SDS-PAGE gels were transferred onto cellulose nitrate membranes for western blotting for antigen confirmation. (f) Analysis of antigen. Coomassie blue stained from SDS-PAGE [M, protein marker and lane 1: positive control (purified protein)], western blotting with purified protein (lane 2), serum from convalescent SARS patient (lane 3) and serum from a healthy volunteer (lane 4).

3.2. Structure and sequence analysis of DNA vaccine

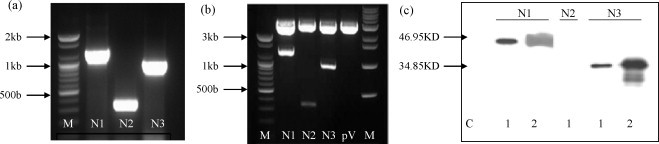

To increase the potency of the specific immune response, the full-length N (N1) and truncated (N2 and N3) genes were ligated into pVAX-1 containing a CMV promoter and BGH polyadenylation sequence. The inserts in plasmid were indicated as pVAX-N1/N2/N3 and sequenced and proved to be correct (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Insert preparation, expression and confirmation of N (N1/N2/N3) protein in mammalian cells (ATCC 293T). (a) PCR products of N1 (1269 bp), N2 (327 bp) and N3 (942 bp), M: DNA marker. (b) Eukaryotic expression vector (pVAX-1) cloning (BamH1 and Pst1 digestion). (c) Expression of the constructs, determined by western blot analysis with antisera reactive with SARS CoV N was evaluated after transfection of the indicated plasmid expression vectors in ATCC 293T cells. C: control (whole cell lysate transfected with vector), lane 1: vector inserted gene (pVAX-N1/pVAX-N2/pVAX-N3), lane 2: Recombinant SARS N (N1/N3) protein as positive control.

3.3. Characterization of N protein in cells transfected with the various DNA vaccines

In order to characterize the expression of the SARS-CoV N protein in 293T cells transfected with the various DNA constructs, we performed a Western blot analysis using cell lysates derived from DNA-transfected cells. Mouse anti-SARS nucleoprotein was used for Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 2c, lysate from 293T cells transfected with N1 and N3 DNA revealed a protein band with a size of approximately 46.95 and 34.85 kDa, respectively. In contrast, N2 protein was not detected in lysates from 293T cells transfected with pVAX-N2 DNA Our data indicated that N DNA-transfected cells exhibited levels of N protein expression comparable to that in plasmid DNA with no insert-transfected cells (control).

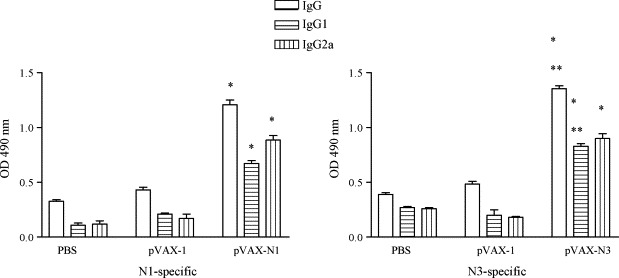

3.4. Detection of antibody titer in mice immunized with the candidate vaccine

To evaluate the humoral immune response to DNA vaccines encoding SARS-CoV N (N1/N3) protein, we performed ELISA analysis using bacterium-derived N (N1/N3) protein and sera from mice ten days after the final vaccination with the two DNA vaccines (pVAX-N1 and pVAX-N3). As shown in Fig. 3 , two groups (pVAX-N1 and pVAX-N3) of vaccinated mice developed substantial antibody responses whereas the animals in the control groups (PBS and pVAX-1) did not show any detectable N-specific IgG and its subtype profile IgG1 and IgG2a antibody response. As shown in Fig. 3, the anti-SARS-CoV IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a were induced by all the immunization regimens. IgG, IgG1 antibody levels in the N3 groups showed higher degrees of increase compared to those in the N1 vaccinated groups, although the IgG2a antibody profiles were more or less similar in both groups.

Fig. 3.

Detection of humoral immune response in the immunized BALB/c mice. Mouse sera were collected 10 days after the final immunization. SARS-CoV N (N1/N3)-specific IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a were assessed. Data are presented as means ± S.D. *p > 0.001 and **p > 0.01.

3.5. N-specific T cells proliferation

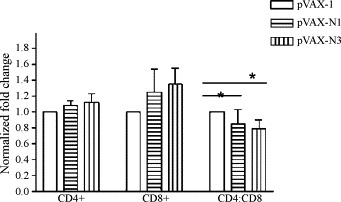

Activation and proliferation of lymphocytes play a critical role in both humoral and cellular immune responses induced by vaccination. Therefore, we next evaluated whether pVAX-N1/N3 vaccination by electroporation and subsequent immunization could influence antigen-specific T-cell proliferation. As shown in Fig. 4 , higher levels of lymphocytes stimulated by N protein were observed in mice immunized with pVAX-N1/N3 compared to controls (pVAX-1 and PBS) (p < 0.01). Cell proliferation in animals immunized with pVAX-N3 was appreciably higher than that in pVAX-N1 immunized animals (p < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

N-specific lymphocyte proliferation assay. Pooled splenocytes were obtained from mice (five mice per group) immunized with the DNA vaccine on day 10 post-immunization. Splenocytes were stimulated in vitro with N protein (N1/N3-test groups), Con A (positive controls), and BSA (irrelevant antigen controls). Splenocytes from the control groups (pVAX-1 or PBS) were stimulated with N protein, and served as negative controls and sham controls. The stimulation index (SI) was calculated using the following formula: SI = (mean OD of Con A or antigen-stimulated proliferation)/(mean OD of non-stimulated proliferation). Each bar represents the mean SI ± S.D. of five mice. *p > 0.01 and **p > 0.05.

3.6. CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes responses

Since activated CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes are among the most crucial components of antiviral effectors, they were assessed in the vaccinated mice (Fig. 5 ). Flow cytometric analysis of unstimulated cells was used to standardize the background responses, and there was little variation in non-immunized mice. Compared with the control group (p < 0.05, the CD8+ T cells increased and the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ decreased in the pVAX-N1 and pVAX-N3 (experimental groups), indicating that cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity was induced by the recombinant plasmid. The CD8+/CD4+ ratio in the N3 groups was higher than that in the N1 groups but the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Changes in CD4+CD8+ ratio of BALB/c mice in different groups. The CD4+ and CD8+ T subtypes were counted on day 10 post-immunization. Compared with the control group, the CD8+ T cells increased and the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ decreased in the experimental group, indicating that CTL activity was induced by the recombinant plasmid. *p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The 2002/2003 SARS epidemic is currently under control. However, the absence of an effective therapeutic agent against this relatively new lethal virus of animal origin, compounded by the threat of its potential for re-emergence, calls for the development of a SARS vaccine. Extensive efforts have been made for the development of a SARS vaccine along a variety of approaches like inactivated whole virus vaccine, subunit vaccines, DNA vaccines, as well as live recombinant vaccines and various animal models of experimental infection by the SARS-CoV have been evaluated.

Results in a study by Tan et al. [5] suggest that as early as 2 days after the onset of illness, there are IgM and IgA anti-N antibodies present in the blood, and by 9 days, IgA levels against N protein are very high. This finding that N protein induces a strong IgA response parallels the findings by Tripp et al. [27] that monoclonal antibodies against N protein are present in the mucosal epithelia, as detected by immunohistochemistry on autopsy samples. These locations include the alveolar epithelium, trachea/bronchus, esophagus, gastric parietal cells and the intestinal tract. Strong immunoreactivity towards N protein suggests that the protein may be released from the virus or from infected cells into the circulation during infection. Alternatively, it may be presented by antigen presenting cells (APCs) for cytolysis of target cells. N protein does not appear to undergo rapid mutation like S protein. Coupled with the fact that S protein is more difficult to express, N protein could be a better target for the development of serological assays.

Similar to studies with S protein, putative antigenic sequences have also been identified for N protein. Using cDNA from full-length N protein expressed in E. coli, fragments were probed with SARS patients’ sera in a study by Chen et al. [28]. Four regions with possible epitopes were identified: amino acids 51–71 (EP1), 134–208 (EP2), 249–273 (EP3) and 349–422 (EP4). While EP2 and EP4 were described as linear epitopes, EP1/EP2 and EP3/EP4 formed conformational epitopes that reacted with sera. As such, structural requirements appear to be important for antigenicity in N protein.

Keeping in mind these protein microarray data, we expressed recombinant N [amino acids: 1–422 (N1); 1–109 (N2) and 110–422 (N3)] proteins in E. coli and prepared N protein-specific monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies for developing a tool for SARS diagnosis. Two kinds of antibodies (N1-Ab, anti-full-length N protein and N3-Ab, anti-partial N protein) were obtained. We have shown N1 and N3 has 100% sensitivity and specificity for SARS-CoV antibody when testing with 10 SARS-CoV positive human sera compared to 50-healthy human sera by ELISA system. We also checked that the polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies do not have the cross-reactivity with the group 1 corona virus (human corona virus-229E and porcine epidemic diarrhea) and group II (human corona virus-OC43 and mouse hepatitis virus) [authors’ unpublished data]. The identification of antigenic N protein fragments offered a potential target site for the design of an epitope-based vaccine against SARS.

In this report, we detected SARS-Cov N1 and N3 protein-specific immune response induced by pVAX-N1 and N3 DNA vaccination, respectively, and found significantly high titres of specific antibody and specific cell mediated immunity compared to control. These results indicate that N protein, which naturally exists in virus particles after binding of viral RNA, was able to induce strong humoral and cellular immune responses when induced by DNA vaccine, and it might be a prospective candidate gene for development of SARS-CoV vaccine. We have shown that DNA vaccination can successfully elicit SARS-CoV N-specific humoral and CD8+ T-cell responses in vaccinated mice. It is also evident that vaccination with pVAX-N3 is more effective than N1. We got the same result in ELISA system that the specificity and sensitivity of N3-antibody is higher than N1-antibody [authors’ unpublished data].

Our data show that middle or C-terminal region of SARS-CoV N protein has antigenicity, but N-terminal region does not, reflecting published reports [29]. The result suggests that the truncated recombinant protein except N-terminal of SARS N protein, containing a highly conserved motif, is more useful for designing a DNA vaccine [3], [30].

The nucleocapsid of corona virus group contains T-cell dependent and independent epitopes. Nude (athymic) mice immunized with HBV-nucleocapsid alone develop high titers of IgM, IgG2a and IgG2b antibodies, which are the predominant antibodies in Th1 responses. There is evidence that the specific structural folding of viral nucleocapsid is responsible for its high immunogenicity [31]. Two more studies analyzed humoral and cell-mediated immune responses in mice immunized with DNA vaccines expressing nucleocapsid.

Kim et al. showed that linkage of nucleocapsid protein to calreticulin increased humoral and cellular immune responses in vaccinated mice compared to mice receiving DNA-nucleocapsid alone. Shi et al. showed that expression of membrane protein augments the specific responses induced by SARS-CoV nucleocapsid DNA immunization. Zhu et al. showed a high level of antibody titer in mice after three injections of DNA-nucleocapsid [7], [32], [33], [34]. The success of immunization depends on several factors, such as type of antigen, route of administration and usage of adjuvants. Widera et al. increased DNA vaccine delivery and immunogenicity by electroporation in vivo [25]. In this study, mice were immunized by electroporation.

DNA immunization has been well modeled in mice for the evaluation of best possible parameters for immunization as also the types of immune responses produced, as is evident from data till date. DNA vaccines also seem promising in human application. However, effects in mice may often be more vivid than those in humans; hence, certain safety issues need to be taken care of regarding immunogenicity of DNA vaccines in humans. DNA vaccines in larger animals are still not totally effective due to significant restrictions with the recent technologies. Many characteristics still remain to be considered prior to the development of a DNA vaccine against SARS-CoV in humans. In our present report, we have illustrated that the presented SARS N DNA vaccine expressing plasmid induces specific immune responses in mouse. However, we did not run tests to check the protective effect with challenge SARS-CoV. Our next target would be to evaluate and establish the efficacy of this SARS DNA (pVAX-N3) vaccine in non-human primate model.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants provided by the Korea Research Foundation and Brain Korea 21 project, South Korea.

References

- 1.Drosten C., Gunther S., Preiser W., Werf S.V.D., Brodt H.R., Becker S. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. New Engl J Med. 2003;348:967–976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marra M.A., Jones S.J., Astell C.R., Holt R.A., Brooks-Wilson A., Butterfield Y.S. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rota P.A., Oberste M.S., Monroe S.S., Nix W.A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J.P. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes K.V., Enjuanes L. The SARS coronavirus: a postgenomic era. Science. 2003;300:1377–1378. doi: 10.1126/science.1086418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan Y.J., Goh P.Y., Fielding B.C., Shen S., Chou C.F., Fu J.L. Profiles of antibody responses against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus recombinant proteins and their potential use as diagnostic markers. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:362–371. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.2.362-371.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo P.C.Y., Lau S.K.P., Wong B.H.L., Tsoi H.W., Fung A.M.Y., Chan K.H.T. Detection of specific antibodies to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus nucleocapsid protein for serodiagnosis of SARS coronavirus pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2306–2309. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.5.2306-2309.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi S.Q., Peng J.P., Li Y.C., Qin C., Liang G.D., Xu L. The expression of membrane protein augments the specific responses induced by SARS-CoV nucleocapsid DNA immunization. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:1791–1798. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enjuanes L., Smerdou C., Castilla J., Anton I.M., Torres J.M., Sola I. Development of protection against coronavirus induced diseases, a review. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;380:197–211. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1899-0_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takamura K., Matsumoto Y., Shimizu Y. Field study of bovine coronavirus vaccine enriched with hemagglutinating antigen for winter dysentery in dairy cows. Can J Vet Res. 2002;66:278–281. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavanagh D. Severe acute respiratory syndrome vaccine development: experiences of vaccination against avian infectious bronchitis coronavirus. Avian Pathol. 2003;32:567–582. doi: 10.1080/03079450310001621198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pratelli A., Tinelli A., Decaro N., Cirone F., Elia G., Roperto S. Efficacy of an inactivated canine coronavirus vaccine in pups. New Microbiol. 2003;26:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pratelli A., Tinelli A., Decaro N., Cirone F., Elia G., Roperto S. Efficacy of an inactivated canine coronavirus vaccine in pups. New Microbiol. 2004;119:129–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saif L.J. Animal coronavirus vaccines: lessons for SARS. Dev. Biol. (Basel) 2004;119:129–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang M.S., Lu Y.T., Ho S.T., Wu C.C., Wei T.Y., Chen C.J. Antibody detection of SARS-CoV spike and nucleocapsid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:931–936. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Surjit M., Liu B., Kumar P., Chow V.T.K., Lal S.K. The nucleocapsid protein of the SARS coronavirus is capable of self-association through a C-terminal 209 amino acid interaction domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317:1030–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo L., Masters P.S. Genetic evidence for a structural interaction between the carboxy termini of the membrane and nucleocapsid proteins of mouse hepatitis virus. J Virol. 2002;76:4987–4999. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4987-4999.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker M.M., Masters P.S. Sequence comparison of the N genes of five strains of the coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus suggests a three-domain structure for the nucleocapsid protein. Virology. 1990;179:463–468. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90316-J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang L.R., Chiu C.M., Yeh S.H., Huang W.H., Hsueh P.R., Yang W.Z. Evaluation of antibody responses against SARS coronaviral nucleocapsid or spike proteins by immunoblotting or ELISA. J Med Virol. 2004;73:338–346. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narayanan K., Chen C.J., Maeda J., Makino S. Nucleocapsid-independent specific viral RNA packaging via viral envelope protein and viral RNA signal. J Virol. 2003;77:2922–2927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.5.2922-2927.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung D.T., Tam F.C., Ma C.H., Chan P.K., Cheung J.L., Niu H. Antibody response of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) targets the viral nucleocapsid. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:379–386. doi: 10.1086/422040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu C., Kokuho T., Kubota T., Watanabe S., Inumaru S., Yokomizo Y., Onodera T. DNA mediated immunization with encoding the nucleoprotein gene of porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus. Virus Res. 2001;80:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(01)00333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao W., Tamin A., Soloff A., D’Aiuto L., Nwanegbo E., Robbins P.D. Effects of a SARS-associated coronavirus vaccine in monkeys. Lancet. 2003;362:1895–1896. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14962-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okada M., Takemoto Y., Okuno Y., Hashimoto S., Yoshida S., Fukunaga Y. The development of vaccines against SARS corona virus in mice and SCID426 PBL/hu MICE. Vaccine. 2005;23:2269–2272. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kon O.L., Sivakumar S., Teoh K.L., Lol S.H., Long Y.C. Naked plasmid-mediated gene transfer to skeletal muscle ameliorates diabetes mellitus. J Gene Med. 1999;1:186–194. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-2254(199905/06)1:3<186::AID-JGM33>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CDC NIH . Biosafety in microbiological and biomedical laboratories. 4th ed. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Widera G., Austin M., Rabussay D., Goldbeck C., Barnett S.W., Chen M. Increased DNA vaccine delivery and immunogenicity by electroporation in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;164:4635–4640. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Froebel K.S., Pakker N.G., Aiuti F., Bofill M., Choremi-Papadopoulou H., Economidou J. Standardization and quality assurance of lymphocyte proliferation assays for use in the assessment of immune function. J Immunol Methods. 1999;227:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tripp R.A., Haynes L.M., Moore D., Anderson B., Tamin A., Harcourt B.H. Monoclonal antibodies to SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV): identification of neutralizing and antibodies reactive to S, N, M and E viral proteins. J Virol Methods. 2005;128:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Z., Pei D., Jiang L., Song Y., Wang J., Wang H. Antigenicity analysis of different regions of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nucleocapsid protein. Clin Chem. 2004;50:988–995. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.031096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shang B., Wang X.Y., Yuan J.W., Vabret A., Wu X.D., Yang R.F. Characterization and application of monoclonal antibodies against N protein of SARS-coronavirus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Q., Yu L., Petros A.M., Gunasekera A., Liu Z., Xu N. Structure of the N450 terminal RNA-binding domain of the SARS-CoV nucleocapsid protein. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6059–6063. doi: 10.1021/bi036155b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noad R., Roy P. Virus-like particles as immunogens. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11:438–444. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(03)00208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim T.W., Lee J.H., Hung C.F., Peng S., Roden R., Wang M.C. Generation and characterization of DNA vaccines targeting the nucleocapsid protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2004;78:4638–4645. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.9.4638-4645.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu M.S., Pan Y., Chen H.Q., Yue S., Chun W.X., Jun S.Y. Induction of SARS458 nucleoprotein-specific immune response by use of DNA vaccine. Immunol Lett. 2004;92:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vandana G., Tani M.T., Kai S., Ananth C., Azlinda A., Kun Y. SARS coronavirus nucleocapsid immunodominant T-cell epitope cluster is common to both exogenous recombinant and endogenous DNA-encoded immunogens. Virology. 2006;347:127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]