Abstract

PURPOSE

The objective of this review was to address the barriers limiting access to genetic cancer risk assessment and genetic testing for individuals with suspected hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) through a review of the diagnosis and management steps of HBOC.

METHODS

A selected panel of Brazilian experts in fields related to HBOC was provided with a series of relevant questions to address before the multiday conference. During this conference, each narrative was discussed and edited by the entire group, through numerous drafts and rounds of discussion, until a consensus was achieved.

RESULTS

The authors propose specific and realistic recommendations for improving access to early diagnosis, risk management, and cancer care of HBOC specific to Brazil. Moreover, in creating these recommendations, the authors strived to address all the barriers and impediments mentioned in this article.

CONCLUSION

There is a great need to expand hereditary cancer testing and counseling in Brazil, and changing current policies is essential to accomplishing this goal. Increased knowledge and awareness, together with regulatory actions to increase access to this technology, have the potential to improve patient care and prevention and treatment efforts for patients with cancer across the country.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 10% and 25% of all breast (BC) and ovarian cancers (OC), respectively, are hereditary.1 Identification of pathogenic germline variants in high-/moderate-penetrance cancer-predisposing genes allows the implementation of strategies for cancer risk reduction and early detection. In Brazil, there is limited access to cancer risk assessment and genetic testing for individuals with suspected hereditary cancer, as well as limited information on its burden in the country. Therefore, the objective of this study was to make harmonized recommendations for improving early detection, risk management, and cancer care of patients with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC).

METHODOLOGY

The Americas Health Foundation convened a 6-member panel of clinical and scientific experts in oncology, gynecology, genetics, and applied genomics from Brazil. PubMed and Embase were used to conduct a literature review and to identify Brazilian experts who have published in the field of HBOC since 2012. To better focus the discussion, Americas Health Foundation staff developed specific questions for the panel to address. A written response to each question was drafted by each expert and was discussed during a multiday meeting. Questions were edited by the entire group, through numerous drafts and rounds of discussion, until complete consensus was obtained.

BURDEN AND EPIDEMIOLOGY OF, AND RISK FACTORS FOR, HBOC

HBOC is a highly penetrant, autosomal dominant disorder mostly caused by pathogenic and likely pathogenic germline variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.1 BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes that repair double-stranded DNA breaks through homologous recombination (HR).2 Individuals harboring germline pathogenic variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are predisposed to BC (lifetime risk up to 85% and 45%, respectively) and OC (lifetime risk up to 39% and 11%, respectively), as well as other malignancies.3-5

The population prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants is 1:150-1:200 individuals in North American and European populations.6 Mutation prevalence varies according to ethnicity, the genetic testing criteria used, age at cancer diagnosis, and family history. The catalog of germline variants in BRCA genes in different populations should be expanded and made available in public databases such as ClinVar and BRCA Challenge.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

How can the diagnosis and management of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer be improved in Brazil? A panel of Brazilian experts proposes recommendations for improving access to early diagnosis, risk management, and cancer care of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.

Knowledge Generated

Understanding Brazil’s unique social and structural barriers is crucial to expanding access to genetic cancer risk assessment. Government, medical societies, patient organizations, academic centers, and the private sector should collaborate to create a multistakeholder commission to develop and promote the incorporation of genetic cancer risk assessment.

Relevance

Increased knowledge and awareness, together with regulatory actions to expand hereditary cancer testing and counseling in Brazil, have the potential to improve the care of patients with cancer and reduce the cancer burden across the country.

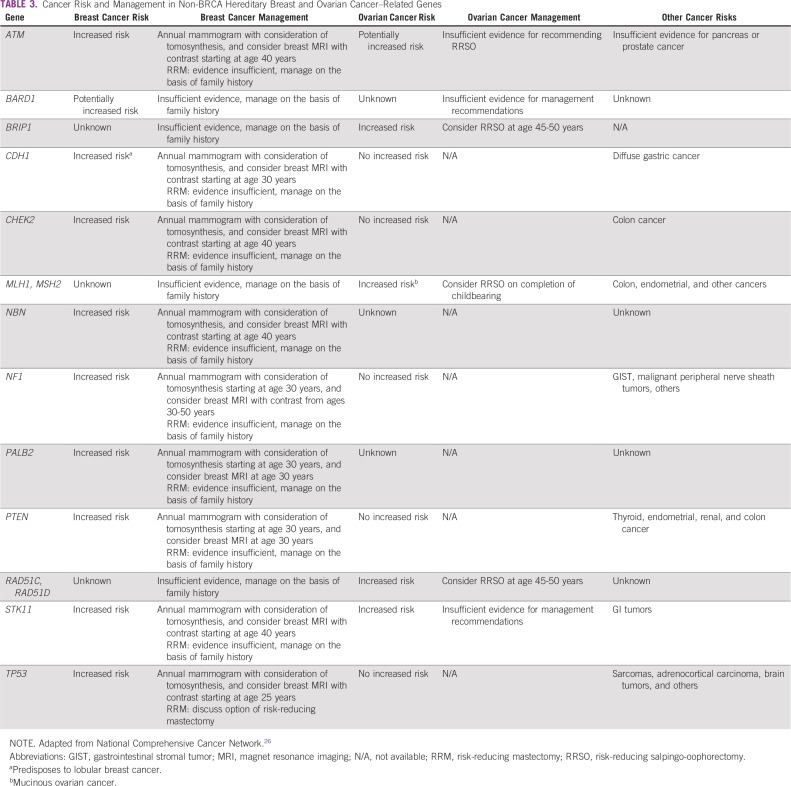

BC and OC risks may be increased by pathogenic variants in other high-penetrance (TP53, PTEN, STK11, CDH1, and PALB2) and moderate-penetrance (CHEK2, ATM, NF1, RAD51C, RAD51D, and BRIP1) genes. The American College of Medical Genetics has recognized 25 actionable genes for which there is enough evidence to implement an effective cancer risk-reduction strategy.7 Cancer risk management has been implemented in BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic carriers, whereas knowledge about the appropriate management of carriers with moderate-penetrance genes is still limited.8

Multigene panel testing, including actionable genes related to BC and OC, may be considered for patients who fulfill the clinical criteria for HBOC.9 Testing only BRCA genes may miss approximately one-half of the pathogenic germline variants involved in HBOC risk,10 and next-generation sequencing allows testing genes with clinical usefulness at an affordable cost.9,11,12 Panel testing should be recommended only by trained physicians to ensure adequate genetic counseling and management. There is no added value of exome and whole-genome testing in HBOC families, and this should not be recommended. Treatment-focused genetic testing (TFGT) and genomic tumor profiling are currently the gold standard in defining better treatment strategies for tumors such as ovarian serous carcinomas. This generates an urgent need to provide more effective, timely, and adequate pre- and post-test genetic counseling.13

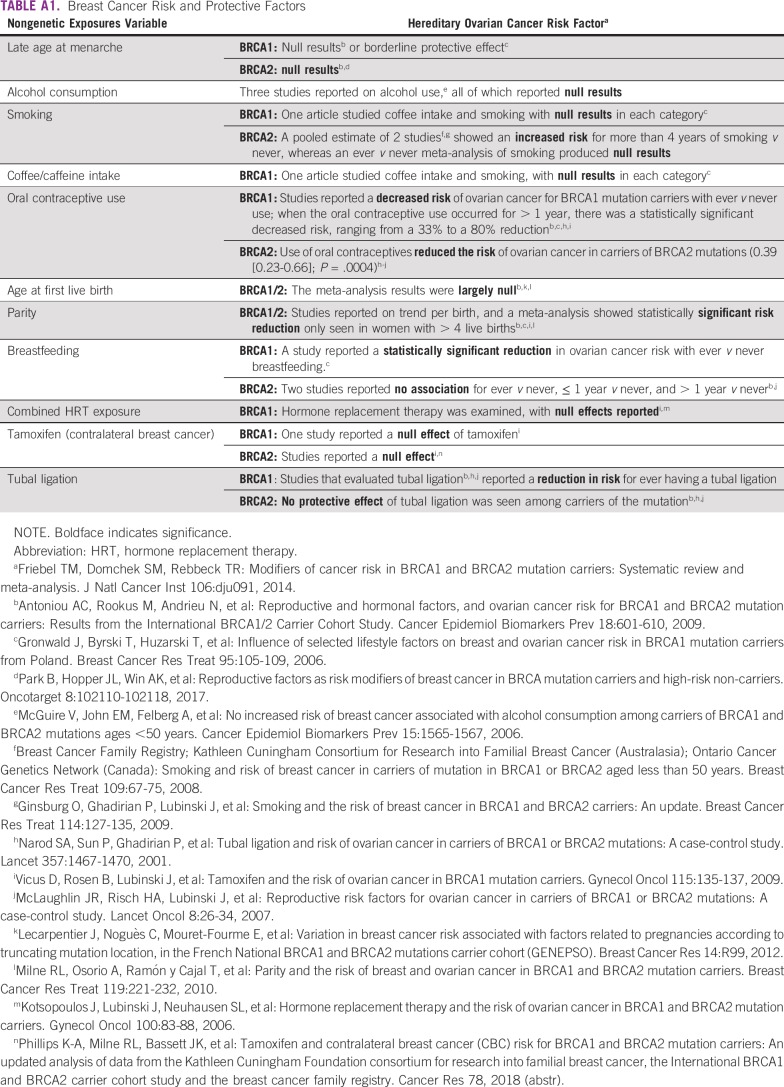

Several genetic and environmental factors can modulate the penetrance of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants. Variant location, with the identification of clusters of mutations with differential cancer risks, may be associated with higher BC or OC risks.14 In addition, several genetic variants have been identified in coding and noncoding regions, which may modulate the penetrance of germline BRCA1/2 variants, such as those described by the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2.15 Risk-protecting factors (eg, breast feeding in BRCA1 carriers) and risk-enhancing factors (eg, obesity) have been identified (Appendix Table A1). Studies on cancer risk modifiers in Brazilian patients with HBOC are not currently available. Such studies are needed to verify whether these cancer risk modifiers have a role in risk management strategies tailored to Brazil’s admixed population.

MOLECULAR EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HBOC

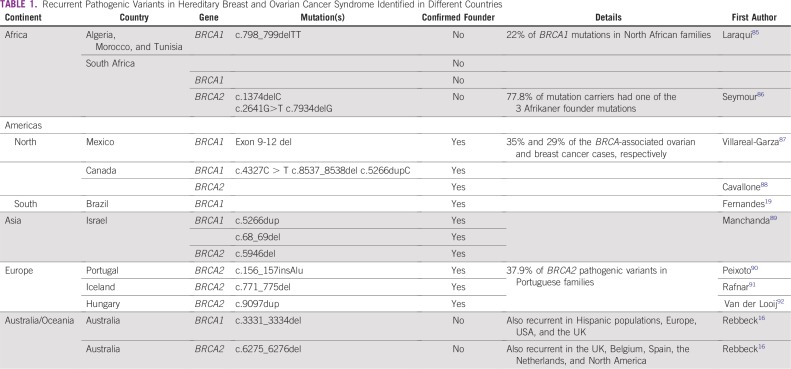

In the mutational landscape of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants in > 29,000 families16 substantial variation in mutation type and frequency by geographical region and race/ethnicity was observed. Recurrent germline BRCA variants have been described in specific populations or geographic regions, and some are caused by founder effects (Table 1). In these situations, mutation-specific screening strategies are efficient, such as the 3 BRCA1 and BRCA2 Ashkenazi founder mutations identified in 2.5% of this population.13 Nine studies have performed comprehensive BRCA mutation testing in 2,090 individuals from high-risk cohorts in Brazil.17-25 Mutation prevalence estimates in individuals with clinical criteria are 19%-22%.26,27 Approximately 5% are large gene rearrangements. Certain variants are specific to Brazilian regions as a result of distinctive patterns of immigration in the past centuries.28,29

TABLE 1.

Recurrent Pathogenic Variants in Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome Identified in Different Countries

HEREDITARY BC RELATED TO TP53 GENE

In Brazil, a significant percentage of BC burden is conferred by Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), because of a founder mutation, TP53 p.Arg337His (p.R337H)(NC_000017.9: c.1010G>A), present in 0.3% of the southern and southeastern populations. LFS has a wide tumor spectrum, predisposing to premenopausal BC, sarcomas, brain tumors, and adrenocortical carcinoma, among other cancers.30 Strong evidence supports the association between the TP53 germline variant and a worse overall and disease-free survival in BC.31-33 In classic LFS, cancer risk by age 60 years is 90% in women and 73% in men, with an overall cumulative incidence of 50% by age 40 years.34,35 The p.R337H TP53 variant confers a lifetime cancer risk that differs from typical DNA-biding domain TP53 pathogenic variants. Carriers have a lifetime cancer risk of 80% in females, and 47% in males.36 BC is the most common malignancy diagnosed in LFS. In p.R337H carriers, the mean age is 40 years, and in classic LFS, 32 years.37 In a cohort of 815 women affected by BC in southern Brazil who developed the disease before age 45 years, the result was a high prevalence of the p.R337H (12.1%).38 These results suggest that inheritance of p.R337H may contribute to a significant number of BC cases in Brazil.

Currently, in Brazil, genetic testing for TP53 mutation is for families who fulfill certain criteria, which may include all cases of BC below age 35 years, regardless of family history.27,39 Recent studies suggested that all women with premenopausal BC in Brazil should be tested for p.R337H.40,41 Effective screening strategies for LFS represent a major challenge because of the wide spectrum of tumors and the variable ages of onset. Given the suspected high population prevalence of the founder mutation in Brazil, and the public health issue it may constitute, a better knowledge of its country-wide prevalence, as well as the effective management of cost-effective strategies dedicated to the Brazilian population, are urgently required.

DIAGNOSIS, MANAGEMENT, COST EFFECTIVENESS, AND TREATMENT OPTIONS IN HBOC IN BRAZIL

Genetic cancer risk assessment (GCRA) is an interdisciplinary medical practice that identifies, counsels, and manages individuals and families at high risk of an inherited cancer syndrome.42 In Brazil, access to GCRA and consequent management options according to established risk are limited. Improving access is essential to increase health and improve cancer outcomes.

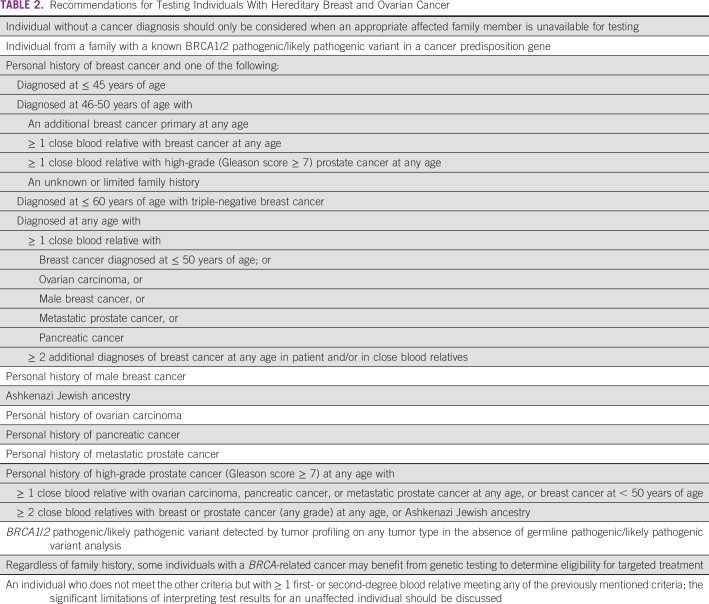

Although genetic testing is not available in the Brazilian public health care system, in the private system, coverage is available for molecular testing in individuals who fulfill criteria established by the Agencia Nacional de Saude.27 Agencia Nacional de Saude guidelines include risk-reducing interventions for carriers of a pathogenic germline variant (eg, risk-reducing surgeries, breast reconstruction, and access to follow-up breast magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] in patients who decline surgery). Meeting the need for adequate post-test counseling is a challenge. Regulatory actions and policy recommendations are urgently needed to address these issues. Table 2 lists the recommendations of this panel in defining criteria for genetic testing for individuals with HBOC in Brazil.

TABLE 2.

Recommendations for Testing Individuals With Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer

Women diagnosed with BC or OC may be offered TFGT, with targeted therapies for BRCA carriers. As the demand for TFGT increases, alternative models of providing information to patients before genetic testing should be sought, because there is a limited number of genetic risk assessment providers. A streamlined approach may be an effective solution. It relies on substituting traditional pretest genetic counseling with providing information, the graphic/visual information to the patient, or focused counseling by the treating physician.43-45

UNDERSTANDING GENETIC TESTING RESULTS

In the presence of germline BRCA1/BRCA2 and TP53 variants, current options for risk reduction and early detection include surveillance and risk-reducing surgeries. In individuals without a previously identified pathogenic variant, the absence of a pathogenic variant cannot definitively exclude hereditary cancer, because some individuals may still harbor an elevated risk of HBOC caused by unknown/unidentified genetic risk factors. In this scenario, models estimating cancer risk on the basis of family history and individual risk factors should be communicated to the patient. It is important to investigate both maternal and paternal lineages to prevent missing additional cancer risk.

Whenever a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) is identified, this result must be considered inconclusive and no clinical action is justified. The Brazilian population is highly admixed, and there is likely an increased prevalence of VUS. Nevertheless, preliminary data have shown a prevalence similar to those of North American and European populations.23 The majority (> 90%) of VUS will be reclassified to benign or likely benign categories.46 Nevertheless, VUS should always be reported and periodically reassessed. Reaching back to patients regarding new, updated testing options or techniques should also be ensured.42,46-49

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

Because of a lack of local studies, all recommendations for Brazil are based on international data. Although surveillance strategies for moderate-penetrance genes have limited data, some screening strategies must be encouraged (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Cancer Risk and Management in Non-BRCA Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer–Related Genes

Intensive Surveillance for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Carriers

An annual breast MRI in conjunction with annual mammography screening in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers from the age of 30 years is more sensitive than annual mammography alone, detecting BC at an earlier stage.50-54 MRI screening every 6 months has shown optimal performance for women at risk of BRCA1-associated BC.55 Although in Brazil these resources are not sufficiently well distributed, breast MRI is fully covered for patients who carry a BRCA pathogenic variant.27 Additional studies to determine the combination of screening modalities, potential harms of exposure to mammography radiation, cost effectiveness, and survival are needed.56,57 Future perspectives in this field include the adoption of abbreviated MRI protocols and the use of less contrast to reduce costs.58,59 OC screening is not recommended. However, in patients who decline risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, transvaginal ultrasound and serum CA-125 may be considered, at the clinician’s discretion.

Risk-Reducing Bilateral Mastectomy for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Carriers

Bilateral mastectomy is associated with > 90% risk reduction in BC.60 In BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers, nipple-sparing mastectomy is associated with a low rate of complications.61,62 Surveillance strategies after risk-reducing mastectomy are not well established and should be addressed on a case-by-case basis. A recent study showed that bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy in mutation carriers had an impact on mortality in BRCA1 carriers, although the impact in BRCA2 carriers was less evident.63

Contralateral Risk-Reducing Mastectomy for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Carriers

Cumulative contralateral BC risk 20 years after a first primary BC is 40% for BRCA1 and 26% for BRCA2 carriers. Current evidence suggests that contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy is effective for BRCA1 carriers, reducing mortality.64-67

Risk-Reducing Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Carriers

Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) confers a 72%-88% risk reduction in OC and fallopian tubal cancer. It is associated with a reduction in OC-specific and all-cause mortality in BRCA carriers.60,68 Therefore, BSO is recommended for BRCA carriers who have completed childbearing, and it should be performed by age 35-40 years in BRCA1 carriers, by age 40-45 years in BRCA2 carriers, or individualized, on the basis of the age of onset of OC in the family. Detailed sectioning and microscopic examination of ovaries and fallopian tubes from BSO in high-risk populations led to the identification of occult carcinomas in up to 1.9%-9.1% of cases.60 After risk-reducing surgery, there is a 10% risk of recurrence after detection of an occult carcinoma and a 1% risk of developing a primary peritoneal tumor.69

Early surgical castration causes early menopause and increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis. On the basis of available data from observational studies, hormone replacement therapy after BSO should not be performed in patients affected by BC, but it has not shown an increased risk of BC among cancer-free BRCA carriers who have undergone risk-reduction bilateral mastectomy.70

Chemoprevention for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Carriers

Large primary prevention trials with tamoxifen, 20 mg once per day for 5 years, have demonstrated that BC risk can be reduced by 40%-50% in women at high risk, although not necessarily in pathogenic variant carriers.71 Limited data are available regarding the benefit of tamoxifen in BRCA carriers, but it may be considered for patients who do not want to undergo risk-reducing surgery.72,73 There are no data on the benefit of raloxifene or aromatase inhibitors in BRCA carriers.

PolyADP-Ribose Polymerases in BRCA-Associated OC for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Carriers

PolyADP-ribose polymerases (PARP) inhibitor is a targeted therapy that acts on a deficiency in the HR pathway. In OC, 2 randomized phase III trials (SOLO-2 and NOVA) demonstrated improved progression-free survival with monotherapy PARP inhibitor as maintenance therapy in patients with recurrent, platinum-sensitive BRCA-associated OC and HR-deficient tumors.74,75 In first-line treatment, SOLO-1 showed better progression-free survival with PARP inhibitor (olaparib) maintenance treatment after usual chemotherapy in BRCA-associated stage III-IV high-grade serous or endometrial OC.76 Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária has approved olaparib for relapsed high-grade OC and for first-line BRCA-associated serous and endometrioid high-grade OC, but it is not yet available to the public or in the private health system.

PARP Inhibitor in BRCA-Associated BC for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Carriers

Two phase III trials (OlympiAD and EMBRACA) randomly assigned patients after chemotherapy in HER2-negative, BRCA-associated metastatic BC and showed longer progression-free survival with PARP inhibitor. The Food and Drug Administration has approved 2 PARP inhibitors (olaparib77 and talazoparib78) for germline BRCA-associated metastatic BC. In Brazil, olaparib was approved in this setting by Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária in 2018.

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS FOR TP53 GERMLINE PATHOGENIC VARIANT CARRIERS

All carriers of a TP53 pathogenic variant should receive intensive surveillance. In Brazil, because of the founder variant present in a significant part of the population, management is a public health situation that remains unresolved. Nevertheless, breast MRI should be offered annually from age 20 years and mammography annually after age 30 years. Risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy and contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy should be suggested. Whole-body MRI and brain MRI should be performed yearly from birth in carriers because of the high risk of sarcomas and CNS, adrenocortical, and other tumors.

COST-EFFECTIVENESS OF GENETIC TESTING

BRCA testing is cost effective in BC and OC. It is associated with reduced risk and improved survival in female carriers, with benefits when testing is extended to family members (cascade testing).79,80 Presymptomatic cancer surveillance is cost effective for patients with germline pathogenic variants in TP53.81

Risk-reduction surgery and intensive breast screening were cost effective in models of BRCA carrier risk management.82 In Brazil, BRCA1/BRCA2 diagnostic and management strategies for patients with OC were considered cost effective but only when cancer-unaffected relatives of OC mutation carriers were included in the model.83

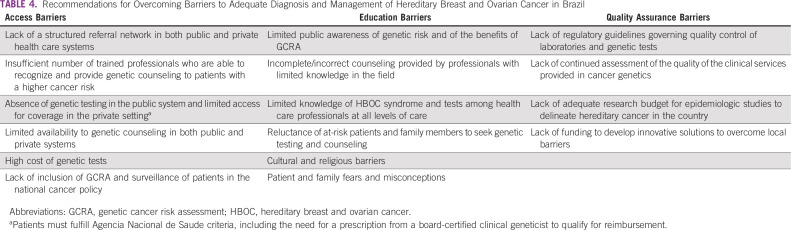

CURRENT BARRIERS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO ADEQUATE DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF HBOC IN BRAZIL

Despite evidence of the benefits of genetic counseling, testing, and adequate risk management,42 access is limited in Brazil and in most Latin American countries (Table 4). To address these limitations, strategies related to public awareness, education, integrated services, implementation, and monitoring are needed. Government, medical societies, patient organizations, academic centers, and the private sector should create a multistakeholder commission to develop and promote the incorporation of GCRA and management into the public and private health care systems. Such a plan should include the following:

TABLE 4.

Recommendations for Overcoming Barriers to Adequate Diagnosis and Management of Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer in Brazil

-

Establishment of genetic health benefits, including genetic testing, counseling, and long-term management, accessible to patients in both public and private health care systems:

The Brazilian National Cancer Control Policy should be updated to include essential genetic health benefits.

Regulatory agencies in the Brazilian Ministry of Health should prioritize the incorporation of policies related to hereditary cancer.

Guidelines that ensure coverage for genetic services in private health care should be updated on an annual basis and should include genetic testing coverage for cancer-unaffected individuals when first- and second-degree relatives fulfill criteria.

-

Development of a 3-tiered training program for health professionals.

Tier 1: Basic genetics education and continued medical education should be provided to all health care professionals to enable recognition and referral of at-risk patients;

Tier 2: A minimum curriculum on hereditary cancer should be included in training programs in specialties related to cancer care, and continuing medical education should be required;

Tier 3: Specialty training programs should be developed and expanded for health care professionals seeking to conduct GCRA.

In TFGT, a streamlined approach should be implemented. Traditional GCRA should be available whenever indicated. Research studies should be conducted to validate whether a streamlined approach is effective in Brazil.

Genetic counseling and risk assessment should be offered in a multidisciplinary setting involving multiple health care professionals to ensure the most appropriate management of patients and their families.

Public health officials should be educated on the importance of GCRA, guaranteeing access to genetic health benefits as part of the strategic national cancer control plan.

A Brazilian network of reference centers should be expanded and the insertion of GCRA and genetic testing should be championed in both public and private health care systems.

Continuing professional education and periodic recertification should be implemented to guarantee clinical and laboratory services. Professional societies should oversee these efforts.

Government, medical societies, health care professionals, and patient organizations should support education programs to promote public awareness of the importance of understanding personal and family genetic risk factors and their influence on cancer management.

Politicians should be encouraged to pass laws protecting individuals against genetic discrimination by employers and insurance companies.

Systematic reporting should be encouraged. Results from clinical and research-focused genetic testing should be made available in public databases on human genomic variations.

There is a great need to expand hereditary cancer testing and counseling in Brazil. Understanding Brazil’s unique social and structural barriers and mounting a strong, timely response to this public health problem is crucial. Increased knowledge and awareness of HBOC among nongenetic health care professionals, as well as the general population, public health officials, and patient organizations, would advance translational efforts to improve cancer care and outcomes.84

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Breast Cancer Risk and Protective Factors

SUPPORT

Supported by a grant from the Americas Health Foundation, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization dedicated to improving health care throughout the Latin American Region, and by an unrestricted grant from AstraZeneca.

The Americas Health Foundation had no role in deciding the content of this article, and the recommendations are those solely of the panel members.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Provision of study material or patients: Maira Caleffi

Collection and assembly of data: Rodrigo Guindalini, Patricia Ashton-Prolla

Data analysis and interpretation: Rodrigo Guindalini, Patricia Ashton-Prolla

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/site/misc/authors.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Maria Isabel Achatz

Speakers' Bureau: AstraZeneca, MSD Oncology

Rodrigo Guindalini

Employment: CLION, Grupo CAM, Oncologia D'or

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Mendelics Análise Genômica

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca Brazil, Merck Brazil

Speakers' Bureau: AstraZeneca, Roche, MSD, Bayer, Merck, Teva, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca, Roche

Angelica Nogueira-Rodrigues

Honoraria: Roche, MSD, AstraZeneca

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, AstraZeneca, MSD, Eisai

Patricia Ashton-Prolla

Research Funding: AstraZeneca Brazil (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Szabo CI, King MC. Inherited breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1811–1817. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.suppl_1.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roy R, Chun J, Powell SN. BRCA1 and BRCA2: Different roles in a common pathway of genome protection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;12:68–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc3181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: A combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1117–1130. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mersch J, Jackson MA, Park M, et al. Cancers associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations other than breast and ovarian. Cancer. 2015;121:269–275. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, et al. Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA. 2017;317:2402–2416. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE, et al. Population BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation frequencies and cancer penetrances: A kin-cohort study in Ontario, Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1694–1706. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): A policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Genet Med 19249–255.2017[Erratum: Genet Med, 2017] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters ML, Garber JE, Tung N. Managing hereditary breast cancer risk in women with and without ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graffeo R, Livraghi L, Pagani O, et al. Time to incorporate germline multigene panel testing into breast and ovarian cancer patient care. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;160:393–410. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buys SS, Sandbach JF, Gammon A, et al. A study of over 35,000 women with breast cancer tested with a 25-gene panel of hereditary cancer genes. Cancer. 2017;123:1721–1730. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eliade M, Skrzypski J, Baurand A, et al. The transfer of multigene panel testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer to healthcare: What are the implications for the management of patients and families? Oncotarget. 2017;8:1957–1971. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robson M, Domchek S.Broad application of multigene panel testing for breast cancer susceptibility-Pandora’s box is opening wider JAMA[epub ahead of print on October 3, 2019] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meiser B, Quinn VF, Gleeson M, et al. When knowledge of a heritable gene mutation comes out of the blue: Treatment-focused genetic testing in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:1517–1523. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rebbeck TR, Mitra N, Wan F, et al. Association of type and location of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with risk of breast and ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2015;313:1347–1361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baquero JM, Benítez-Buelga C, Fernández V, et al. A common SNP in the UNG gene decreases ovarian cancer risk in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Mol Oncol. 2019;13:1110–1120. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rebbeck TR, Friebel TM, Friedman E, et al. Mutational spectrum in a worldwide study of 29,700 families with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2018;39:593–620. doi: 10.1002/humu.23406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carraro DM, Koike Folgueira MA, Garcia Lisboa BC, et al. Comprehensive analysis of BRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53 germline mutation and tumor characterization: A portrait of early-onset breast cancer in Brazil. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva FC, Lisboa BC, Figueiredo MC, et al. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: Assessment of point mutations and copy number variations in Brazilian patients. BMC Med Genet. 2014;15:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-15-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandes GC, Michelli RA, Galvão HC, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in a Brazilian population sample at-risk for hereditary breast cancer and characterization of its genetic ancestry. Oncotarget. 2016;7:80465–80481. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maistro S, Teixeira N, Encinas G, et al. Germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in epithelial ovarian cancer patients in Brazil. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:934. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2966-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alemar B, Herzog J, Brinckmann Oliveira Netto C, et al. Prevalence of Hispanic BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among hereditary breast and ovarian cancer patients from Brazil reveals differences among Latin American populations. Cancer Genet. 2016;209:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alemar B, Gregório C, Herzog J, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutational profile and prevalence in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) probands from Southern Brazil: Are international testing criteria appropriate for this specific population? PLoS One 12e01876302017 [Erratum: PLoS One, 2018] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmero EI, Carraro DM, Alemar B, et al. The germline mutational landscape of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Brazil. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9188. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27315-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Souza Timoteo AR, Gonçalves AEMM, Sales LAP, et al. A portrait of germline mutation in Brazilian at-risk for hereditary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;172:637–646. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4938-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felix GE, Abe-Sandes C, Machado-Lopes TM, et al. Germline mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2 and TP53 in patients at high-risk for HBOC: Characterizing a Northeast Brazilian Population. Hum Genome Var. 2014;1:14012. doi: 10.1038/hgv.2014.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN guidelines. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx

- 27.Agencia Nacional de Saúde Resolução Normativa – RN N° 428 de 7 de Novembro deo 2017. http://www.ans.gov.br/component/legislacao/?view=legislacao&task=PDFAtualizado&format=raw&id=MzUwMg==

- 28.Salzano FM, Bortolini MC. The Evolution and Genetics of Latin American Populations. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pena SD, Di Pietro G, Fuchshuber-Moraes M, et al. The genomic ancestry of individuals from different geographical regions of Brazil is more uniform than expected. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li FP, Fraumeni JF, Jr, Mulvihill JJ, et al. A cancer family syndrome in twenty-four kindreds. Cancer Res. 1988;48:5358–5362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Børresen-Dale AL. TP53 and breast cancer. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:292–300. doi: 10.1002/humu.10174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olivier M, Langerød A, Carrieri P, et al. The clinical value of somatic TP53 gene mutations in 1,794 patients with breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1157–1167. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silwal-Pandit L, Vollan HK, Chin SF, et al. TP53 mutation spectrum in breast cancer is subtype specific and has distinct prognostic relevance. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:3569–3580. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mai PL, Khincha PP, Loud JT, et al. Prevalence of cancer at baseline screening in the National Cancer Institute Li-Fraumeni syndrome cohort. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1640–1645. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masciari S, Dillon DA, Rath M, et al. Breast cancer phenotype in women with TP53 germline mutations: A Li-Fraumeni syndrome consortium effort. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:1125–1130. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-1993-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mastellaro MJ, Seidinger AL, Kang G, et al. Contribution of the TP53 R337H mutation to the cancer burden in southern Brazil: Insights from the study of 55 families of children with adrenocortical tumors. Cancer. 2017;123:3150–3158. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Achatz MI, Zambetti GP. The inherited p53 mutation in the Brazilian population. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6:a026195. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giacomazzi J, Graudenz MS, Osorio CA, et al. Prevalence of the TP53 p.R337H mutation in breast cancer patients in Brazil. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chompret A, Abel A, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, et al. Sensitivity and predictive value of criteria for p53 germline mutation screening. J Med Genet. 2001;38:43–47. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrade KC, Santiago KM, Fortes FP, et al. Early-onset breast cancer patients in the south and southeast of Brazil should be tested for the TP53 p.R337H mutation. Genet Mol Biol. 2016;39:199–202. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2014-0343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hahn EC, Bittar CM, Vianna FSL, et al. TP53 p.Arg337His germline mutation prevalence in southern Brazil: Further evidence for mutation testing in young breast cancer patients. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0209934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weitzel JN, Blazer KR, MacDonald DJ, et al. Genetics, genomics and cancer risk assessment: State of the art and future directions in the era of personalized medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:327–359. doi: 10.3322/caac.20128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quinn VF, Meiser B, Kirk J, et al. Streamlined genetic education is effective in preparing women newly diagnosed with breast cancer for decision making about treatment-focused genetic testing: A randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Genet Med. 2017;19:448–456. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colombo N, Huang G, Scambia G, et al. Evaluation of a streamlined oncologist-led BRCA mutation testing and counseling model for patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1300–1307. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Copson ER, Maishman TC, Tapper WJ, et al. : Germline BRCA mutation and outcome in young-onset breast cancer (POSH): A prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 19:169-180, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slavin TP, Manjarrez S, Pritchard CC, et al. The effects of genomic germline variant reclassification on clinical cancer care. Oncotarget. 2019;10:417–423. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Easton DF, Pharoah PD, Antoniou AC, et al. Gene-panel sequencing and the prediction of breast-cancer risk. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2243–2257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1501341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crawford B, Adams SB, Sittler T, et al. Multi-gene panel testing for hereditary cancer predisposition in unsolved high-risk breast and ovarian cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;163:383–390. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4181-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mersch J, Brown N, Pirzadeh-Miller S, et al. Prevalence of variant reclassification following hereditary cancer genetic testing. JAMA. 2018;320:1266–1274. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuhl C, Weigel S, Schrading S, et al. Prospective multicenter cohort study to refine management recommendations for women at elevated familial risk of breast cancer: The EVA trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1450–1457. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le-Petross HT, Whitman GJ, Atchley DP, et al. Effectiveness of alternating mammography and magnetic resonance imaging for screening women with deleterious BRCA mutations at high risk of breast cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:3900–3907. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Riedl CC, Luft N, Bernhart C, et al. Triple-modality screening trial for familial breast cancer underlines the importance of magnetic resonance imaging and questions the role of mammography and ultrasound regardless of patient mutation status, age, and breast density. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1128–1135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phi XA, Saadatmand S, De Bock GH, et al. Contribution of mammography to MRI screening in BRCA mutation carriers by BRCA status and age: Individual patient data meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:631–637. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:75–89. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guindalini RSC, Zheng Y, Abe H, et al. Intensive surveillance with biannual dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging downstages breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:1786–1794. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pijpe A, Andrieu N, Easton DF, et al. Exposure to diagnostic radiation and risk of breast cancer among carriers of BRCA1/2 mutations: Retrospective cohort study (GENE-RAD-RISK) BMJ. 2012;345:e5660. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Plevritis SK, Kurian AW, Sigal BM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of screening BRCA1/2 mutation carriers with breast magnetic resonance imaging. JAMA. 2006;295:2374–2384. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.20.2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pataky R, Armstrong L, Chia S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of MRI for breast cancer screening in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:339. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuhl CK, Schrading S, Strobel K, et al. Abbreviated breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): First postcontrast subtracted images and maximum-intensity projection-a novel approach to breast cancer screening with MRI. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2304–2310. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.5386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ludwig KK, Neuner J, Butler A, et al. Risk reduction and survival benefit of prophylactic surgery in BRCA mutation carriers, a systematic review. Am J Surg. 2016;212:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yao K, Liederbach E, Tang R, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers: An interim analysis and review of the literature Ann Surg Oncol 22370–376.2015[Erratum: Ann Surg Oncol 21:S788, 2014] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jakub JW, Peled AW, Gray RJ, et al. Oncologic safety of prophylactic nipple-sparing mastectomy in a population with BRCA mutations: A multi-institutional study. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:123–129. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heemskerk-Gerritsen BAM, Jager A, Koppert LB, et al. Survival after bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy in healthy BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;177:723–733. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05345-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boughey JC, Hoskin TL, Degnim AC, et al. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy is associated with a survival advantage in high-risk women with a personal history of breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2702–2709. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1136-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lostumbo L, Carbine NE, Wallace J. Prophylactic mastectomy for the prevention of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(11):CD002748. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002748.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Metcalfe K, Gershman S, Ghadirian P, et al. Contralateral mastectomy and survival after breast cancer in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: Retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g226. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Evans DG, Ingham SL, Baildam A, et al. Contralateral mastectomy improves survival in women with BRCA1/2-associated breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;140:135–142. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2583-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.George SH, Shaw P. BRCA and early events in the development of serous ovarian cancer. Front Oncol. 2014;4:5. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Powell CB, Chen LM, McLennan J, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) in BRCA mutation carriers: Experience with a consecutive series of 111 patients using a standardized surgical-pathological protocol. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:846–851. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821bc7e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kotsopoulos J, Gronwald J, Karlan BY, et al. Hormone replacement therapy after oophorectomy and breast cancer risk among BRCA1 mutation carriers. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1059–1065. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Bonanni B, et al. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators in prevention of breast cancer: An updated meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2013;381:1827–1834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60140-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.King MC, Wieand S, Hale K, et al. Tamoxifen and breast cancer incidence among women with inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP-P1) Breast Cancer Prevention Trial. JAMA. 2001;286:2251–2256. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phillips KA, Milne RL, Rookus MA, et al. Tamoxifen and risk of contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3091–3099. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.8313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1274–1284. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, et al. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2154–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495–2505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1810858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation N Engl J Med 377523–533.2017[Erratum: N Engl J Med, 2017] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, et al. Talazoparib in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:753–763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tuffaha HW, Mitchell A, Ward RL, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of germ-line BRCA testing in women with breast cancer and cascade testing in family members of mutation carriers. Genet Med. 2018;20:985–994. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eccleston A, Bentley A, Dyer M, et al. A cost-effectiveness evaluation of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing in UK women with ovarian cancer. Value Health. 2017;20:567–576. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tak CR, Biltaji E, Kohlmann W, et al. Cost-effectiveness of early cancer surveillance for patients with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66:e27629. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Müller D, Danner M, Schmutzler R, et al. : Economic modeling of risk-adapted screen-and-treat strategies in women at high risk for breast or ovarian cancer. Eur J Health Econ 20:739-750, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ramos MCA, Folgueira MAAK, Maistro S, et al. Cost effectiveness of the cancer prevention program for carriers of the BRCA1/2 mutation. Rev Saude Publica. 2018;52:94. doi: 10.11606/S1518-8787.2018052000643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mitropoulos K, Al Jaibeji H, Forero DA, et al. Success stories in genomic medicine from resource-limited countries. Hum Genomics. 2015;9:11. doi: 10.1186/s40246-015-0033-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Laraqui A, Uhrhammer N, Rhaffouli HE, et al. BRCA genetic screening in Middle Eastern and North African: Mutational spectrum and founder BRCA1 mutation (c.798_799delTT) in North African. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:194293. doi: 10.1155/2015/194293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Seymour HJ, Wainstein T, Macaulay S, et al. Breast cancer in high-risk Afrikaner families: Is BRCA founder mutation testing sufficient? S Afr Med J. 2016;106:264–267. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i3.10285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Villarreal-Garza C, Alvarez-Gómez RM, Pérez-Plasencia C, et al. Significant clinical impact of recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Mexico. Cancer. 2015;121:372–378. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cavallone L, Arcand SL, Maugard CM, et al. Comprehensive BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation analyses and review of French Canadian families with at least three cases of breast cancer. Fam Cancer. 2010;9:507–517. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9372-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Manchanda R, Loggenberg K, Sanderson S, et al. Population testing for cancer predisposing BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in the Ashkenazi-Jewish community: A randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;107:379. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Peixoto A, Santos C, Pinheiro M, et al. International distribution and age estimation of the Portuguese BRCA2 c.156_157insAlu founder mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:671–679. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rafnar T, Benediktsdottir KR, Eldon BJ, et al. BRCA2, but not BRCA1, mutations account for familial ovarian cancer in Iceland: A population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2788–2793. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Van Der Looij M, Szabo C, Besznyak I, et al. Prevalence of founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations among breast and ovarian cancer patients in Hungary. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:737–740. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000601)86:5<737::aid-ijc21>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]