Abstract

Over 300 million surgical procedures are performed every year worldwide. Anesthesiologists play an important role in the perioperative process by assessing the overall risk of surgery and aim to reduce the risk of complications. Perioperative hemodynamic and volume management can help to improve outcomes in perioperative patients. There has been ongoing discussion about goal-directed therapy. However, there is a consensus that fluid overload and severe fluid depletion in the perioperative period are harmful and can lead to adverse outcomes. This article provides an overview of how to evaluate the fluid responsiveness of patients, details which parameters could be used, and what limitations should be noted.

Keywords: Cardiac output monitoring, Colloids, Crystalloid solutions, Hemodynamic monitoring, Hypotension, Volume therapy

Introduction

Anesthesiologists play an important role in the perioperative process by assessing the overall risk of surgery, including the risk factors of the surgical procedure and those of the patient. There have been substantial developments over the last few decades regarding the risk of anesthesia. In the early days of anesthesia, the risk of the anesthetic procedure itself was high and led to a number of fatalities [1,2]. This has changed dramatically, and these days anesthesia-related deaths are extremely low. Such advances are likely related to drug advancements, an improved understanding of physiology, and better monitoring and management. However, death after surgery, including the whole perioperative process, has not substantially declined. The risk of death during the 30 days following surgery is 1,000 times more likely than during surgery itself [3]. According to recent data, death within 30 days of surgery is the third leading cause of death in the United States of America, behind cardiac diseases and malignancy [4].

Some recent studies have assessed this risk in detail. According to Weiser et al. [5], it is estimated that more than 310 million surgical procedures are performed worldwide. The exact complication rate and risk of death after these procedures are largely unknown. However, it is estimated that depending on the type of surgery and patient’s comorbidities that about 30–40% of patients develop complications, of which up to 20% are severe and possibly life-threatening [6–8]. Besides, the mortality risk of surgery is not precisely known. It has been estimated that between 3 and 12 million patients die worldwide after surgery. The European Surgical Outcome study evaluated this in detail in a seven-day cohort study that included 46,539 patients from 498 European centers. Patients were followed for up to 60 days after their surgical procedure. Of this cohort, 1,855 patients died while in hospital, giving an in-hospital mortality rate of 4.7%. Additionally, the study found that there was substantial variation in the risk-adjusted mortality between European centers. These results highlight an opportunity to learn from those centers with lower risk-adjusted mortality rates to improve patient outcomes in other centers [9].

Perioperative hemodynamic and volume management are important considerations in improving outcomes in perioperative patients. There has been ongoing discussion on which fluid should be used, and at what rate it should be administered to particular patients. There is a consensus that fluid overload and severe fluid depletion in the perioperative period is harmful and leads to adverse outcomes [10]. Unfortunately, adequate management of volume therapy is challenging and requires additional testing and monitoring that is seldom used in clinical practice, even in high-risk patients [11,12].

Physiology of volume replacement

Adequate fluid and volume therapy during and after anesthesia is important for improving perioperative outcomes. Without a doubt, the most common intervention done by anesthesiologists is prescribing fluids. Fluids are important as normovolemia is an essential factor of hemodynamic stability and homeostasis between the intravascular fluid and extravascular space. However, the traditional concept to give fluids where hemodynamic compromise is recognized (e.g., hypotension), following the principle “in doubt give volume”, has been proven to be incorrect [13]. Notably, in abdominal surgery, the concept of “restrictive” fluid therapy that was introduced in the early 2000s was quite successful and led to better outcomes compared to the traditional liberal volume therapy [14]. In particular, complications that were associated with fluid overload like pulmonary edema, anastomotic leakage, anemia, coagulopathy, and cardiovascular compromise dramatically reduced, which led to better outcomes overall. However, in further studies, “restrictive” and “liberal” were not well defined, and what was considered restrictive in one study was deemed liberal by others [15]. In some studies, an extremely restrictive approach led to severe hemodynamic compromise with decreased perfusion, decreased oxygen delivery, and complications like acute kidney injury (AKI) [16].

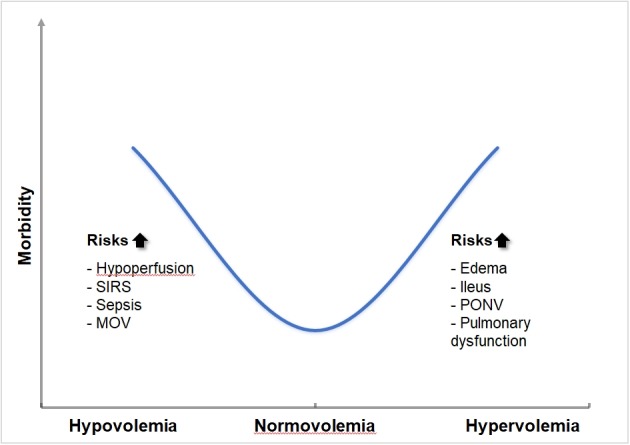

Fluid overload is recognized as being harmful. Unfortunately, fluid overload is common, silent, and deadly. Bellamy [17] put together a theoretical framework based on their concept that there is a U-shape relationship between fluid therapy and outcome. Excess fluid overload and severe fluid restriction can both lead to adverse outcomes. Therefore, anesthesiologists need to find a balance and ascertain the ideal volume status for individual patients. This is termed normovolemia (Fig. 1). Two retrospective studies recently showed that fluid overload and hypovolemia are associated with unfavorable outcomes such as AKI, pulmonary complications, and even mortality [10,13]. Therefore, it is important to recognize the need for fluid in some patients and deresucitation in others. Thus, we need to clearly define our aim when giving patients fluids. Do we want to expand the extracellular space to compensate for losses, or do we want to increase the intravascular space to improve the filling pressures and potentially cardiac output (CO)? In this review, only volume therapy, giving additional fluids to improve hemodynamic parameters, will be discussed. Fluid therapy, which is mostly used to compensate extravascular losses and regain fluid homeostasis in internal medicine patients, is beyond the scope of this article and will not be discussed.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between morbidity and hypo- normo- and hypervolemia. Bellamy [17] developed a theoretical framework based on their concept that there is a U-shape relationship between fluid therapy and outcome. Therefore, prevention of hypo- and hypervolemia by goal-directed fluid management is essential. SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome, MOV: multiple organ failure, PONV: postoperative nausea and vomiting.

Before giving patients additional fluid, we need to ascertain whether the issue can be solved by increasing stroke volume and cardiac output. However, usually, we do not want to increase only cardiac output. In most cases, we aim to increase oxygen delivery to the tissues. However, to achieve this, global oxygen delivery needs to first be increased. Currently, we cannot be sure that this will also lead to increased oxygen delivery to individual tissues as monitoring of the microcirculation, while possible, has not gained general acceptance in clinical practice [18]. In a review article, Monnet and Teboul [19] detailed all of the circumstances in which a volume bolus will lead to increased tissue perfusion and function. The first step is to increase the mean systemic filling pressure, which can be counteracted by capillary leakage and venodilatation. The role of making artificial and natural colloids more effective so as to increase the mean systemic filling pressure has been extensively discussed. However, as yet, no conclusions have been reached. Nevertheless, colloids appear to be more able to achieve this with less fluid and a longer intravascular half-life. Therefore it is only moderately surprising that colloids, including starches, were used in 86% of the included studies in a review of fluid boluses [20]. This was done despite several studies showing that in critically ill patients, the use of colloids, and in particular starches, can result in an increased risk of renal failure and death [21–23]. However, a recent meta-analysis did not confirm these findings in surgical patients [24,25]. It is paramount that the patient is fluid responsive and that the stroke volume can be increased by additional fluid loading, given that the aim is to increase global oxygen delivery. After fluid loading, not all patients that have increases in their stroke volume and cardiac index shows better microcirculatory flow and increased oxygen consumption. Further research is needed to identify the mechanisms for uncoupling the global perfusion indices from regional indexes and identifying suitable treatment algorithms.

As optimized global perfusion is a prerequisite to optimizing microperfusion, in the following section, methods to assess the need for intravascular volume therapy to increase stroke volume will be critically discussed.

How to assess fluid responsiveness

The concept of determining the treatment effects of therapies is not new. If we administered vasopressors and did not measure arterial blood pressure before and after the intervention, we would be accused of malpractice. However, when we administer fluids during surgery, the verification of a positive drug effect, and the decision to give fluids is often made with little testing or indications. Almost a hundred years ago, Prof. Jarisch [26] asserted that our understanding of circulation was limited as while blood pressure is easily measured, blood flow is not. This is why blood pressure monitoring is so prevalent despite most organs requiring blood flow, not pressure. However, if we do not measure blood flow, how can we know that additional volume given to patients is actually increasing blood flow? A recent study by Cecconi et al. [27] tried to elucidate what drives the decision to give additional volume to intensive care unit (ICU) patients. In 42.7% of the patients, no testing of fluid responsiveness took place, and the decision was only based on clinical experience. In another 35.5%, the decision was based on static parameters like central venous pressure (CVP) or atrial blood pressure that we will discuss below. The second most interesting finding of this study was that despite the results of testing, about 50% in all groups (positive, negative, and uncertain) received additional fluids.

Pressure based volume therapy – arterial blood pressure, CVP

Generally, in recent years, a large amount of fluids has been given to patients undergoing surgery, especially when there was some sort of hemodynamic deterioration like hypotension. The idea behind this was that a “liberal” policy of fluid management in surgical patients is required. This concept is based on ideas and studies from Tom Shires, Chief of Surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, Texas [28]. His work led him to conclude that an extracellular fluid deficit in surgical patients and the consequent elevations of aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone is caused by extravasations of fluid from the extracellular compartment to the third space along with evaporative losses [29,30]. A strategy of aggressive fluid replacement emerged as the mainstay of perioperative care to compensate for these losses [31,32]. However, hypotension can occur quite often during surgical procedures, and in many cases, hypotension is not linked with hypovolemia. Intraoperative hypotension has been studied for many years. Therefore, it is surprising that there is still no clear definition of intraoperative hypotension. In a review by Bijker et al. [33] of 130 studies, 140 different definitions of hypotension were described. Risk factors for hypotension besides hypovolemia are increased age, a higher American Society of Anesthesiologists score, induction medication that might lead to vasodilatation, and neuro-axial anesthesia. Also, during different time frames of anesthesia, various risk factors have been published, describing post-induction hypotension, early intraoperative hypotension, and late intraoperative hypotension [34,35]. Hypovolemia is only one potential cause of hypotension. Therefore, any given arterial blood pressure cannot be used to decide whether additional fluid should be provided to a patient to increase cardiac output. Nevertheless, hypotension, in conjunction with the wider clinical picture, can help to find an indication to give fluid. In polytraumatized patients with ongoing bleeding, the first step is to give fluids. However, during procedures, it is not possible to tell when resuscitation is complete, and normovolemia is reached just by measuring the arterial blood pressure.

Another option might be to measure venous filling pressures like CVP or pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PCWP). The measurement of filling pressures was long advocated for in many guidelines, such as the surviving sepsis campaign [36]. This guideline recommended that patients should receive additional fluids to optimize perfusion until their CVP was 8–12 or 12–15 cmH2O, if mechanically ventilated. Unfortunately, this has been proven to be incorrect. Filling pressures like CVP and PCWP are influenced by many other factors that are not related to the fluid status or fluid responsiveness such as cardiac compliance, intra-abdominal pressure, airway pressure and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), pulmonary vascular resistance, and cardiac pathologies such as mitral/tricuspid regurgitation and congestive heart failure. Extensive research, including several meta-analyses, have been conducted on this subject and have concluded that CVP and PCWP should not be used to decide whether to give additional fluids [37,38].

Nevertheless, there is some value in measuring the CVP curve. Recent work that focused on different waves of the CVP curve found some association with preload dependence compared to no preload dependence [39,40]. However, this work must still be viewed as preliminary, particularly as no study has tested these findings with a large number of patients using a multicenter approach. Yet, the absolute number of CVP might also play an important role. Even when an absolute number of CVP does not preclude fluid-responsiveness, it can be used to assess the risk of adverse outcomes. As the CVP is the “zero-mark” of the cardiovascular system, it plays an important role in venous return and microcirculation. Therefore, severely elevated CVP values can be used as a symptom of fluid challenges, even in patients who remain fluid responsive [41]. It has been shown that CVP values over 15 mmHg are associated with increased rates of unfavorable outcomes like AKI [42].

Therefore, in these patients, CVP can be used as a marker of when to stratify increased risk versus the benefits of further fluid loading.

Stroke volume-based volume therapy

One easy method to test whether stroke volume can be increased through fluid loading is to give patients a defined volume bolus and measure it before and after the intervention. This concept is based on the physiological framework of Frank and Starling. Until a certain cut-off regarding the preload of the left ventricle, it can increase its stroke volume. Therefore, only patients that are below this cut-off should receive additional fluids, and this is best estimated by using the steep part of the Frank-Starling curve. Small increases in preload will lead to relatively large increases in stroke volume. Unfortunately, this cut-off varies between people and can also change during different loading conditions. This is especially troublesome as, therefore, all static parameters like filling pressures (CVP and PCWP), and volumetric measures such as global end-diastolic volume cannot provide a specific cut-off number for fluid responsiveness.

A fluid challenge is a maneuver in which a defined bolus of fluid is given within a short time frame. In most cases, this is an artificial colloid. In a recent review, it was asserted that the bolus is relatively standardized within the goal-directed hemodynamic therapy (GDT) literature, and is 250 ml [20]. In 86% of the studies, a colloid was used. It is important that the fluid bolus is given relatively rapidly so that it can stretch the right ventricle to detect an increase in stroke volume in responders. Therefore, most authors apply the bolus within 5–10 minutes or less. If the bolus is too small or given too slowly so that an acute increase of the right ventricular end-diastolic volume is not reached, there is a risk of a false negative test. Most authors recommend measuring stroke volume before and after the fluid challenge. An increase in stroke volume of at least 10–15% is considered a positive response [43]. Theoretically, any device that can measure stroke volume could be used. However, most studies use uncalibrated pulse wave analysis technology.

A fluid challenge is included in many algorithms used to optimize hemodynamics, also called hemodynamic GDT [44]. One of the simplest algorithms is to measure stroke volume, give a fluid challenge, and repeat this until the stroke volume no longer increases by more than 10%. These simple algorithms are easy to follow with high implementation rates. However, if the trigger is hypotension, repeated negative fluid challenges, especially in the ICU, can lead to a substantial positive fluid balance. An unsuccessful fluid challenge does not significantly increase stroke volume and, therefore, might decrease oxygen delivery due to inherent hemodilution if blood is not used for the fluid challenge.

Volume therapy based on dynamic parameters

Another way to optimize the fluid status of patients is by using dynamic parameters like stroke volume variation (SVV), pulse pressure variation (PPV), or pleth variability index (PVI). The dynamic preload parameters, SVV and PPV, are based on changes in the arterial pressure waveform due to changes in stroke volume in relation to positive pressure ventilation. The PVI is an algorithm that allows for the continuous and automatic estimation of respiratory variations in the pulse oximeter waveform amplitude to assess fluid responsiveness. To use these parameters for GDT, it is mandatory to continuously measure the blood pressure or the pulse oximeter waveform amplitude. Today there are a variety of technologies available that can measure this invasively and non-invasively. Various studies have shown that SVV and PPV are better predictors of fluid responsiveness than the static parameters CVP, PCWP, and mean arterial pressure (MAP). SVV (area under the curve [AUC] 0.84) and PPV (AUC 0.94) are good predictors of fluid responsiveness with clinically acceptable levels of sensitivity (0.82 and 0.89) and specificity (0.86 and 0.88) [45]. The cut-off for SVV has been published to be between 10% and 12% [46]. Benes et al. [47] investigated the hemodynamic goal-directed protocol based on SVV in high-risk surgery patients undergoing an elective abdominal operation. The results showed that the GDT-group had better intraoperative hemodynamic stability, a decrease in serum lactate at the end of the surgery, and a lower incidence of postoperative organ complications in comparison with the control group.

Scheeren et al. [48] investigated a combination of SVV and stroke volume optimization in 64 high-risk surgery patients, which were divided into two groups. The primary outcome measure was the number of postoperative complications. The authors could show that an SVV and stroke volume optimization protocol is feasible and can decrease postoperative wound infections. The number of patients with at least one complication (46% vs. 62%) and the number of postoperative complications per patient tended to be lower in the study group.

Other studies investigated PPV as a goal for GDT. The best cut-off value for predicting fluid responsiveness has been published to be between 10% and 15% [49]. Salzwedel and colleagues [50] performed a multi-center study in 160 patients undergoing major abdominal surgery and showed that hemodynamic GDT using PPV, cardiac index trending, and MAP led to a significant decrease in postoperative complications.

Even though the dynamic parameters are better predictors of fluid responsiveness, they have some significant limitations. First, the patient needs to be mechanically ventilated without spontaneous breathing. The published cutoffs in fluid responsiveness for SVV and PVV were validated in patients with a tidal volume > 8 ml/kg. So, if the patient is ventilated with a lower tidal volume, the patient may be false negative for volume responsiveness. Another limitation is that it can display a low heart rate/respiratory ratio. In patients with extreme bradycardia or high respiratory rate (e.g., high-frequency ventilation), the results may be falsely negative for predicting fluid responsiveness. Another special situation is patients undergoing open-chest procedures. In such situations, the PPV (AUC 0.55) and SVV (AUC 0.49) show a low predictive power and should also be used with caution because the results may be falsely negative [51]. In spontaneous breathing patients and patients with arrhythmia, dynamic parameters cannot be used as ventricular filling depends on the variation of diastolic filling in severe arrhythmia, and there is no controlled stimulus in spontaneous breathing patients.

Volume therapy based on physiologic testing

Passive leg raising (PLR)

Widely known for treating acute circulatory failure, passive leg raising (PLR) has gained increasing interest in the perioperative prediction of fluid responsiveness. PLR is a safe method for reversible and rapid autotransfusion of approximately 300 ml of blood without the need for further fluid boli [52,53]. Since the accuracy of PLR is not dependent on a sinus rhythm or high tidal volume, ventilation can also be applied when dynamic preload parameters are not viable. On the other hand, surgical procedures which are not compatible with the movement of legs or the Trendelenburg position (e.g., neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery of the lower limbs) represent relative contraindications for PLR.

Even though most studies investigating PLR derive from critically ill patients, the predictive value can also be assumed for perioperative patients. A meta-analysis that summarized 23 studies investigating the diagnostic accuracy of PLR (measured with flow-based hemodynamic monitoring tools) showed that the pooled sensitivity of PLR was 86% (95% CI: 79%–92%), while its specificity was 92% (95% CI: 88%–96%). This shows its high diagnostic performance in predicting fluid responsiveness [54]. A second systematic review of 991 patients was able to confirm these findings but emphasized the need to measure CO as a target parameter in order to achieve reliable results [55]. It must be highlighted that PLR can be used to decide whether fluid therapy is needed or not. However, even though its practical implementation appears to be simple, some pitfalls have to be thoroughly considered to increase its predictive accuracy. Monnet and Teboul [53] summarized these as; The measurement starts from the semi-recumbent and not from a supine position and should target CO or its indices as opposed to blood pressure. CO can be assessed with different devices (e.g., echocardiography, pulse contour analysis), but it is of high importance that the measurements can detect rapid changes (<1 min). Furthermore, the procedure does not end by the patient´s reposition but with a postinterventional observation period until the hemodynamic situation has been normalized. The depth of anesthesia should be appropriate to avoid sympathetic activation, and adrenergic stimulation blurring the effect of PLR. If these factors are taken into consideration, PLR can be considered a powerful diagnostic tool for predicting perioperative fluid responsiveness and is recommended by several international guidelines [56–58].

End-expiratory occlusion test (EEOT)

A decade ago, Monnet et al. [59] introduced EEOT. The underlying principle of EEOT is based on the influence of deep inspiration on cardiac preload. By carrying out a short (15–30 seconds) end-expiratory occlusion in mechanically ventilated patients, CO is impaired while the atrial filling is simultaneously facilitated, leading to an increase of ventricular stroke volume. To receive a reliable prediction of fluid responsiveness, continuous CO measurement is necessary during EEOT [60]. Furthermore, an EEOT-induced change of 5% of CO is generally accepted as proof of fluid responsiveness [60]. Pulse contour analysis superiorly performs to echocardiography in terms of the precise detection of CO changes during EEOT [61]. However, other devices such as echocardiography, non-invasive CO measurements, and Doppler-based methods are feasible but need more confirmative studies [20,62,63].

EEOT imitates a fluid challenge without the need for fluid application. In contrast to the PLR test, the patient does not need to be moved, making it an attractive solution for surgery. Its predictive value was confirmed in several studies for patients ventilated with tidal volumes ≥8 ml/kg. However, its accuracy in patients ventilated with smaller tidal volumes is still being debated [20,59,60,64–66]. Most studies investigating EEOT under low-tidal volume ventilation derive from an intensive care setting and cannot be directly transmitted to surgery [65,67]. Only one study involving neurosurgical patients directly compared the effects of low- to regular-tidal volume ventilation on the accuracy of EEOT, and showed a very low predictive value of EEOT under low-tidal volume ventilation (AUC of the change of cardiac index 0.53 [95% CI: 0.35–0.71]) [68]. Guinot et al. [66] published the only study showing a low predictive value of EEOT for fluid responsiveness under sufficient tidal volumes (of 8.2 ml/kg) in a heterogeneous study of surgical patients. The reason for these findings remains unclear, but differences between the perioperative and intensive care ventilation strategies might be a factor. However, it has been shown that the level of PEEP does not affect the reliability of EEOT [69].

Novel physiological tests for predicting fluid responsiveness

End-tidal carbon dioxide concentration (PETCO2) is a surrogate for CO and is well-known for detecting successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation. It has been shown that PETCO2 directly correlates to CO and can sufficiently predict fluid responsiveness when combined with PLR testing [70,71]. Tusman et al. [72] introduced a further method based on volumetric CO2 measurements by quantifying the amount of exhaled CO2 instead of the concentration. To detect a lack of intravascular fluids, the patient´s fluid responsiveness was provoked with an elevation of PEEP from 5 to 10 cmH2O for one minute. During this, patients were monitored with volumetric capnography and pulse contour analysis. Afterward, patients received 500 ml of crystalloids, and the measurements were repeated. A decrease of exhaled CO2 volume during the PEEP challenge was predictive of fluid responsiveness. Furthermore, a ROC-analysis revealed a high predictive performance that was superior to the change of end-tidal CO2 concentration and PPV. Even though this method is only available in ventilated patients, it offers a non-invasive and accurate approach for predicting fluid responsiveness that is worthy of further validation [72,73].

In 2005, the respiratory systolic variation test (RSVT) was introduced for predicting fluid responsiveness in surgical patients [74]. The RSVT is performed through the application of three consecutive inspiratory breaths with increasing peak inspiratory pressures (of 10, 20, and 30 cmH2O) and the simultaneous detection of the three lowest systolic arterial pressures. Next, this blood pressure is correlated to the peak pressure of the inspiratory breath, resulting in an RSVT slope. The slope corresponds to the Frank-Starling curve-enhancing a physiologic comprehension of the fluid challenge and is comparable to PPV and SVV in predicting fluid responsiveness [74,75].

Deresuscitation strategies using monitoring of volume status

Originally, the term deresuscitation was used to describe a strategy that aimed to treat fluid overload following the resuscitation and stabilization of critically ill patients. Fluid therapy is used to restore the intravascular volume homeostasis to achieve sufficient tissue oxygenation and can be characterized by the Resuscitation, Optimization, Stabilization, and Evacuation (ROSE) concept [76,77]. First, patients must be resuscitated from circulatory shock (resuscitation). To avoid adverse outcomes associated with fluid overload, fluid responsiveness should be guided by validated tests such as PLR and EEOT (optimization and stabilization). After stabilization of the patient´s hemodynamic status, de-escalation should be considered early and monitored with tests for fluid responsiveness (evacuation) [76]. The goal of the evacuation, deresuscitation phase, is to restore the patient´s physiologic homeostatic intravascular balance and to eliminate superfluous fluids. In the intensive care setting, this can be performed with restrictive volume therapy, diuretics, and/or renal replacement therapy. It has been shown that a negative fluid balance over three days predicts an improved ICU survival rate [76–78]. However, two questions arise: First, what is the best approach to guide deresuscitation, and second, should we consider deresuscitation strategies in the perioperative setting?

To treat fluid overload, it first has to be accurately diagnosed. Assuming that fluid non-responders reflect patients with balanced or overloaded fluid status, a possible approach could be to identify them using fluid responsiveness tests. Since these patients do not benefit from a volume challenge, it can be assumed that CO does not decrease through fluid removal. Besides, fluid removal can be performed until the fluid responsive tests return positive results. In addition to PLR and EEOT, dynamic preload parameters, body weight quantification, bioimpedance measurements, and respiratory variations of the diameter of the inferior cava vein have been evaluated as treatment goals for deresuscitation [73,76,79–83]. To reduce adverse outcomes after acute lung injury, Cordemans et al. [84] used intra-abdominal pressure and the extravascular lung water index to guide the treatment protocol. This consisted of high PEEP levels, small volume resuscitation with albumin, and fluid removal (PLA - treatment, [PEEP, albumin, and Lasix®]). However, the role of albumin in critically ill patients has to be further investigated because two prospective studies failed to show a beneficial effect of albumin therapy [85,86]. While the Furosemide and Albumin for Diuresis of Edema study failed to proof feasibility [86], the Albumin Italian Outcome Sepsis study showed no improvement in the 90-day survival rate after targeting an albumin plasma level ≥ 30 g/L over 28 days after septic shock [85].

Since the phases of ROSE do not generally apply to surgical patients, it cannot be directly adopted in the perioperative setting. However, it is well-known that perioperative fluid overload is associated with adverse outcomes and should be avoided [87–89]. Hence, smart perioperative volume therapy should prevent fluid overload and the need for perioperative deresuscitation. Over the last decade, several GDT protocols have been introduced and evaluated. A recent meta-analysis summarized 95 randomized-controlled trials and was able to show a GDT-induced reduction in mortality, morbidity, and length of hospital stay [90]. Contrastingly, the Optimisation of Cardiovascular Management to Improve Surgical Outcome (OPTIMISE) study was not able to prove the benefits of GDT [88]. The OPTIMISE study protocol aimed to maximize CO by optimizing it individually with fluids until no increase of stroke volume was detectable with further support from dopexamine. Since no reduction of mortality or morbidity was detected, it can be questioned if a maximized CO target is reasonable. Additionally, it is unclear as to whether patients should receive fluids until their preload capacity is completely exploited [73,91]. Hence, modern GDT protocols do not aim for a maximized CO but rather utilize personalized hemodynamic GDT management with multiple parameters for assessing blood flow and fluid responsiveness [91]. Even though the beneficial effects of personalized GDT are indisputable, only a small degree of patients receive this hemodynamic management. This highlights the need for its greater implementation in daily anesthetic routines [12].

Fluid overload is a common issue following the stabilization of critically ill patients. Deresuscitation strategies using tests for fluid responsiveness as well as hyperoncotic infusion combined with diuretics, and renal replacement therapy, might help to remove the extra fluids and increase survival. However, further high-quality studies are required to confirm these findings. Furthermore, the role of deresuscitation must be discussed in terms of intensifying actions for preventing perioperative fluid overload. To achieve this, personalized hemodynamic treatment goals combined with GDT protocols appear to be an effective approach.

Conclusions

Adverse outcomes after surgery are still common, with surgery considered one of the leading causes of death. Many prospective and retrospective studies have shown that volume management and fluid overload can have detrimental effects on postoperative outcomes. Therefore, strategies that help to prevent fluid overload and assess the individual need for volume during and after surgery should be implemented to increase patient safety. In many patients, no monitoring of volume therapy is performed, or inadequate static parameters are used, such as arterial blood pressure, venous filling pressures, or volumetric parameters that cannot assess fluid responsiveness. As a gold standard to assess whether patients can benefit from an increase of stroke volume and, therefore, potentially by an increase in oxygen delivery, dynamic testing should be performed. This can be done using dynamic parameters like SVV or PPV or by forced manipulation of the preload, e.g., by a volume challenge, PLR, or another physiological testing method.

In combination with a goal-directed hemodynamic monitoring protocol and the application of vasopressors and inotrope medication, a reduction of mortality by 58 was observed in a recent meta-analysis [90]. Whether goal-directed volume therapy can reduce perioperative mortality still needs to be demonstrated in larger multicenter studies. Whether the concept of using suitable parameters for goal-directed deresuscitation reduces complication rates, and mortality in the perioperative setting still awaits confirmation by larger trials. Nevertheless, this concept appears to be promising.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contributions

Michael Sander (Conceptualization; Supervision; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing)

Emmanuel Schneck (Conceptualization; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing)

Marit Habicher (Conceptualization; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing)

References

- 1.Macintosh RR. Deaths under anaesthetics. Br J Anaesth. 1949;21:107–36. doi: 10.1093/bja/21.3.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braz LG, Braz DG, Cruz DS, Fernandes LA, Módolo NSP, Braz JR. Mortality in anesthesia: a systematic review. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009;64:999–1006. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009001000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vascular Events In Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) Study Investigators. Devereaux PJ, Chan MT, Alonso-Coello P, Walsh M, Berwanger O, et al. Association between postoperative troponin levels and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2012;307:2295–304. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sessler DI, Khanna AK. Perioperative myocardial injury and the contribution of hypotension. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:811–22. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiser TG, Haynes AB, Molina G, Lipsitz SR, Esquivel MM, Uribe-Leitz T, et al. Estimate of the global volume of surgery in 2012: an assessment supporting improved health outcomes. Lancet. 2015;385 Suppl 2:S11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60806-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1368–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0903048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schilling PL, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer JD. Prioritizing quality improvement in general surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:698–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.06.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahan BC, Koulenti D, Arvaniti K, Beavis V, Campbell D, Chan M, et al. Critical care admission following elective surgery was not associated with survival benefit: prospective analysis of data from 27 countries. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:971–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4633-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearse RM, Moreno RP, Bauer P, Pelosi P, Metnitz P, Spies C, et al. Mortality after surgery in Europe: a 7 day cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:1059–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61148-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin CH, Long DR, McLean D, Grabitz SD, Ladha K, Timm FP, et al. Effects of intraoperative fluid management on postoperative outcomes. Ann Surg. 2018;267:1084–92. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funcke S, Sander M, Goepfert MS, Groesdonk H, Heringlake M, Hirsch J, et al. Practice of hemodynamic monitoring and management in german, austrian, and swiss intensive care units: the multicenter cross-sectional icu-cardioman study. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:49. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0148-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmad T, Beilstein CM, Aldecoa C, Moreno RP, Molnar Z, Novak-Jankovic V, et al. Variation in haemodynamic monitoring for major surgery in european nations: secondary analysis of the EuSOS dataset. Perioper Med. 2015;4:8. doi: 10.1186/s13741-015-0018-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thacker JK, Mountford WK, Ernst FR, Krukas MR, Mythen MM. Perioperative fluid utilization variability and association with outcomes: considerations for enhanced recovery efforts in sample us surgical populations. Ann Surg. 2016;263:502–10. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandstrup B, Tønnesen H, Beier-Holgersen R, Hjortsø E, Ørding H, Lindorff-Larsen K, et al. Effects of intravenous fluid restriction on postoperative complications: comparison of two perioperative fluid regimens. Ann Surg. 2003;238:641–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094387.50865.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perel A, Habicher M, Sander M. Bench-to-bedside review: functional hemodynamics during surgery - should it be used for all high-risk cases? Crit Care. 2013;17:203. doi: 10.1186/cc11448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holte K, Foss NB, Andersen J, Valentiner L, Lund C, Bie P, et al. Liberal or restrictive fluid administration in fast-track colonic surgery: a randomized, double-blind study. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:500–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellamy MC. Wet, dry or something else? Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:755–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ince C, Ertmer C. Hemodynamic coherence: Its meaning in perioperative and intensive care medicine. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2016;30:395–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monnet X, Teboul JL. My patient has received fluid. How to assess its efficacy and side effects? Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8:54. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0400-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Messina A, Pelaia C, Bruni A, Garofalo E, Bonicolini E, Longhini F, et al. Fluid challenge during anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:1353–64. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myburgh JA, Finfer S, Bellomo R, Billot L, Cass A, Gattas D, et al. Hydroxyethyl starch or saline for fluid resuscitation in intensive care. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1901–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB, Tenhunen J, Klemenzson G, Åneman A, et al. Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.42 versus ringer's acetate in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:124–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gattas DJ, Dan A, Myburgh J, Billot L, Lo S, Finfer S, et al. Fluid resuscitation with 6 % hydroxyethyl starch (130/0.4 and 130/0.42) in acutely ill patients: systematic review of effects on mortality and treatment with renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:558–68. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2840-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin C, Jacob M, Vicaut E, Guidet B, Van Aken H, Kurz A. Effect of waxy maize-derived hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 on renal function in surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:387–94. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31827e5569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gillies MA, Habicher M, Jhanji S, Sander M, Mythen M, Hamilton M, et al. Incidence of postoperative death and acute kidney injury associated with i.v. 6% hydroxyethyl starch use: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:25–34. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarisch A. Fortschritte der gesamten Medizin. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1928;19:1211–3. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cecconi M, Hofer C, Teboul JL, Pettilä V, Wilkman E, Molnar Z, et al. Fluid challenges in intensive care: the fenice study. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1529–37. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3850-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habicher M, Perrino A, Spies CD, Heymann Von C, Wittkowski U, Sander M. Contemporary fluid management in cardiac anesthesia. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2011;25:1141–53. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shires T, Williams J, Brown F. Acute change in extracellular fluids associated with major surgical procedures. Ann Surg. 1961;154:803–10. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196111000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts JP, Roberts JD, Skinner C, Illner H, Canizaro PC, Shires GT. Extracellular fluid deficit following operation and its correction with ringers lactate - a reassessment. Ann Surg. 1985;202:1–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198507000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenkins MT, Giesecke AH, Johnson ER. The postoperative patient and his fluid and electrolyte requirements. Br J Anaesth. 1975;47:143–50. doi: 10.1093/bja/47.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell IT, Baxter JN, Tweedie IE, Taylor GT, Keens SJ. IV fluids during surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1990;65:726–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/65.5.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bijker JB, van Klei WA, Kappen TH, van Wolfswinkel L, Moons KG, Kalkman CJ. Incidence of intraoperative hypotension as a function of the chosen definition: literature definitions applied to a retrospective cohort using automated data collection. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:213–20. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000270724.40897.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Südfeld S, Brechnitz S, Wagner JY, Reese PC, Pinnschmidt HO, Reuter DA, et al. Post-induction hypotension and early intraoperative hypotension associated with general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:57–64. doi: 10.1093/bja/aex127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saugel B, Reese PC, Sessler DI, Burfeindt C, Nicklas JY, Pinnschmidt HO, et al. Automated ambulatory blood pressure measurements and intraoperative hypotension in patients having noncardiac surgery with general anesthesia: a prospective observational study. Anesthesiology. 2019;131:74–83. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2016;43:304–77. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marik PE, Baram M, Vahid B. Does central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness?: a systematic review of the literature and the tale of seven mares. Chest. 2008;134:172–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marik PE, Monnet X, Teboul JL. Hemodynamic parameters to guide fluid therapy. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:1. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haddad F, Elmi-Sarabi M, Fadel E, Mercier O, Denault AY. Pearls and pitfalls in managing right heart failure in cardiac surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2016;29:68–79. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy S, Couture P, Qizilbash B, Toupin F, Levesque S, Carrier M, et al. Hemodynamic pressure waveform analysis in predicting fluid responsiveness. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013;27:676–80. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marik PE. Iatrogenic salt water drowning and the hazards of a high central venous pressure. Ann Intensive Care. 2014;4:21. doi: 10.1186/s13613-014-0021-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Legrand M, Dupuis C, Simon C, Gayat E, Mateo J, Lukaszewicz AC, et al. Association between systemic hemodynamics and septic acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: a retrospective observational study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R278. doi: 10.1186/cc13133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cecconi M, Parsons AK, Rhodes A. What is a fluid challenge? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:290–5. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834699cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Habicher M, Balzer F, Mezger V, Niclas J, Müller M, Perka C, et al. Implementation of goal-directed fluid therapy during hip revision arthroplasty: a matched cohort study. Perioper Med (Lond) 2016;5:31. doi: 10.1186/s13741-016-0056-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marik PE, Cavallazzi R, Vasu T, Hirani A. Dynamic changes in arterial waveform derived variables and fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2642–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a590da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hofer CK, Senn A, Weibel L, Zollinger A. Assessment of stroke volume variation for prediction of fluid responsiveness using the modified FloTrac™ and PiCCOplus™ system. Crit Care. 2008;12:R82. doi: 10.1186/cc6933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benes J, Chytra I, Altmann P, Hluchy M, Kasal E, Svitak R, et al. Intraoperative fluid optimization using stroke volume variation in high risk surgical patients: results of prospective randomized study. Crit Care. 2010;14:R118. doi: 10.1186/cc9070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheeren TW, Wiesenack C, Gerlach H, Marx G. Goal-directed intraoperative fluid therapy guided by stroke volume and its variation in high-risk surgical patients: a prospective randomized multicentre study. J Clin Monit Comput. 2013;27:225–33. doi: 10.1007/s10877-013-9461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pinsky MR. Cardiopulmonary interactions: physiologic basis and clinical applications. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15 (Suppl 1):S45–8. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201704-339FR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salzwedel C, Puig J, Carstens A, Bein B, Molnar Z, Kiss K, et al. Perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic therapy based on radial arterial pulse pressure variation and continuous cardiac index trending reduces postoperative complications after major abdominal surgery: a multi-center, prospective, randomized study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R191. doi: 10.1186/cc12885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Waal EE, Rex S, Kruitwagen CL, Kalkman CJ, Buhre WF. Dynamic preload indicators fail to predict fluid responsiveness in open-chest conditions. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:510–5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181958bf7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Monnet X, Teboul JL. Passive leg raising. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:659–63. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-0994-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Monnet X, Teboul JL. Passive leg raising: five rules, not a drop of fluid! Crit Care. 2015;19:18–3. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0708-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cherpanath TG, Hirsch A, Geerts BF, Lagrand WK, Leeflang MM, Schultz MJ, et al. Predicting fluid responsiveness by passive leg raising: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 23 clinical trials. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:981–91. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monnet X, Marik P, Teboul JL. Passive leg raising for predicting fluid responsiveness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1935–47. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marx G, Schindler AW, Mosch C, Albers J, Bauer M, Gnass I, et al. Intravascular volume therapy in adults. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016;33:488–521. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miller TE, Myles PS. Perioperative fluid therapy for major surgery. Anesthesiology. 2019;130:825–32. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Navarro LH, Bloomstone JA, Auler JOC, Cannesson M, Rocca GD, Gan TJ, et al. Perioperative fluid therapy: a statement from the international fluid optimization group. Perioper Med (Lond) 2015;4:3. doi: 10.1186/s13741-015-0014-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Monnet X, Osman D, Ridel C, Lamia B, Richard C, Teboul JL. Predicting volume responsiveness by using the end-expiratory occlusion in mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:951–6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181968fe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gavelli F, Teboul JL, Monnet X. The end-expiratory occlusion test: please, let me hold your breath! Crit Care. 2019;23:274. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2554-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beurton A, Teboul JL, Gavelli F, Gonzalez FA, Girotto V, Galarza L, et al. The effects of passive leg raising may be detected by the plethysmographic oxygen saturation signal in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2019;23:19. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2306-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dépret F, Jozwiak M, Teboul JL, Alphonsine JE, Richard C, Monnet X. Esophageal doppler can predict fluid responsiveness through end-expiratory and end-inspiratory occlusion tests. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:e96–102. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jozwiak M, Dépret F, Teboul JL, Alphonsine JE, Lai C, Richard C, et al. Predicting fluid responsiveness in critically ill patients by using combined end-expiratory and end-inspiratory occlusions with echocardiography. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:e1131–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Biais M, Larghi M, Henriot J, de Courson H, Sesay M, Nouette-Gaulain K. End-expiratory occlusion test predicts fluid responsiveness in patients with protective ventilation in the operating room. Anesth Analg. 2017;125:1889–95. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yonis H, Bitker L, Aublanc M, Perinel Ragey S, Riad Z, Lissonde F, et al. Change in cardiac output during trendelenburg maneuver is a reliable predictor of fluid responsiveness in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in the prone position under protective ventilation. Crit Care. 2017;21:295. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1881-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guinot PG, Godart J, de Broca B, Bernard E, Lorne E, Dupont H. End-expiratory occlusion manoeuvre does not accurately predict fluid responsiveness in the operating theatre. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:1050–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Myatra SN, Prabu NR, Divatia JV, Monnet X, Kulkarni AP, Teboul JL. The changes in pulse pressure variation or stroke volume variation after a “tidal volume challenge” reliably predict fluid responsiveness during low tidal volume ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:415–21. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Messina A, Montagnini C, Cammarota G, De Rosa S, Giuliani F, Muratore L, et al. Tidal volume challenge to predict fluid responsiveness in the operating room. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2019;36:583–91. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Silva S, Jozwiak M, Teboul JL, Persichini R, Richard C, Monnet X. End-expiratory occlusion test predicts preload responsiveness independently of positive end-expiratory pressure during acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1692–701. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Monge García MI, Gil Cano A, Gracia Romero M, Monterroso Pintado R, Pérez Madueño V, Díaz Monrové JC. Non-invasive assessment of fluid responsiveness by changes in partial end-tidal CO2 pressure during a passive leg-raising maneuver. Ann Intensive Care. 2012;2:9. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Monnet X, Bataille A, Magalhaes E, Barrois J, Le Corre M, Gosset C, et al. End-tidal carbon dioxide is better than arterial pressure for predicting volume responsiveness by the passive leg raising test. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:93–100. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2693-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tusman G, Groisman I, Maidana GA, Scandurra A, Arca JM, Bohm SH, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of pulmonary carbon dioxide elimination for noninvasive assessment of fluid responsiveness. Anesth Analg. 2016;122:1404–11. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Monnet X, Marik PE, Teboul JL. Prediction of fluid responsiveness: an update. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6:111. doi: 10.1186/s13613-016-0216-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Preisman S. Predicting fluid responsiveness in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: functional haemodynamic parameters including the respiratory systolic variation test and static preload indicators. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:746–55. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Trepte CJ, Eichhorn V, Haas SA, Stahl K, Schmid F, Nitzschke R, et al. Comparison of an automated respiratory systolic variation test with dynamic preload indicators to predict fluid responsiveness after major surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:736–42. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Malbrain ML, Van Regenmortel N, Saugel B, De Tavernier B, Van Gaal PJ, Joannes-Boyau O, et al. Principles of fluid management and stewardship in septic shock: it is time to consider the four D's and the four phases of fluid therapy. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8:66. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0402-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Malbrain ML, Marik PE, Witters I, Cordemans C, Kirkpatrick AW, Roberts DJ, et al. Fluid overload, de-resuscitation, and outcomes in critically ill or injured patients: a systematic review with suggestions for clinical practice. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2014;46:361–80. doi: 10.5603/AIT.2014.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Silversides JA, Fitzgerald E, Manickavasagam US, Lapinsky SE, Nisenbaum R, Hemmings N, et al. Deresuscitation of patients with iatrogenic fluid overload is associated with reduced mortality in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:1600–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brotfain E, Koyfman L, Toledano R, Borer A, Fucs L, Galante O, et al. Positive fluid balance as a major predictor of clinical outcome of patients with sepsis/septic shock after icu discharge. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:2122–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bagshaw SM, Cruz DN. Fluid overload as a biomarker of heart failure and acute kidney injury. Contrib Nephrol. 2010;164:54–68. doi: 10.1159/000313721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mehta RL, Bouchard J. Controversies in acute kidney injury: effects of fluid overload on outcome. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;174:200–11. doi: 10.1159/000329410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saugel B, Vincent JL, Wagner JY. Fluid overload fades away! time for fluid stewardship. J Crit Care. 2018;48:458–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Malbrain ML, Huygh J, Dabrowski W, De Waele JJ, Staelens A, Wauters J. The use of bio-electrical impedance analysis (bia) to guide fluid management, resuscitation and deresuscitation in critically ill patients: a bench-to-bedside review. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2014;46:381–91. doi: 10.5603/AIT.2014.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cordemans C, de Laet I, Van Regenmortel N, Schoonheydt K, Dits H, Martin G, et al. Aiming for a negative fluid balance in patients with acute lung injury and increased intra-abdominal pressure: a pilot study looking at the effects of pal-treatment. Ann Intensive Care. 2012;2 Suppl 1:S15. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-2-S1-S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Caironi P, Tognoni G, Masson S, Fumagalli R, Pesenti A, Romero M, et al. Albumin replacement in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1412–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oczkowski SJ, Klotz L, Mazzetti I, Alshamsi F, Chen ML, Foster G, et al. Furosemide and albumin for diuresis of edema (fade): a parallel-group, blinded, pilot randomized controlled trial. J Crit Care. 2018;48:462–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gupta R, Gan TJ. Peri-operative fluid management to enhance recovery. Anaesthesia. 2015;71 Suppl 1:40–5. doi: 10.1111/anae.13309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pearse RM, Harrison DA, MacDonald N, Gillies MA, Blunt M, Ackland G, et al. Effect of a perioperative, cardiac output-guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm on outcomes following major gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized clinical trial and systematic review. JAMA. 2014;311:2181–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sun Y, Chai F, Pan C, Romeiser JL, Gan TJ. Effect of perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic therapy on postoperative recovery following major abdominal surgery-a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2017;21:141. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1728-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chong MA, Wang Y, Berbenetz NM, McConachie I. Does goal-directed haemodynamic and fluid therapy improve peri-operative outcomes?: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018;35:469–83. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Saugel B, Vincent JL, Wagner JY. Personalized hemodynamic management. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23:334–41. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]