Abstract

In the last decades, more complex types of residential mobility, such as second homes, arose while one-way relocations declined. Existing studies that address migration and commuting as being substitutes often face problems of endogeneity or lack of data regarding decision-making on different types of residential mobility. In contrast, we investigate decision-making on migration, commuting, and establishing a second home by using a factorial survey experiment, which allows for the accounting of both endogeneity bias through randomisation and complexity in decision-making through treatment variation. Hypothetical job offers were presented to a sample of academic staff of a Swiss university (ETH Zurich) in order to examine the intended types of residential mobility and their drivers. Referring to the concept of loss aversion, the utility of a second home can exceed the joint utilities of migration and commuting particularly when the total loss of the current residence bears intolerable costs caused by location-specific capital, and daily commuting bears prohibitive costs caused by a lengthy distance. Analyses show that the migration intention is mainly caused by low migration and high transition costs and the commuting intention is mainly caused by low transition costs and high migration costs. Establishing a second home is indeed more intended with simultaneously higher migration and transition costs. In sum, a second home may be understood as a substitute for one-way relocations and daily commuting, yet primarily under conditions of extremely high or irreversible migration costs and unsustainable transition costs.

Keywords: Migration, Commuting, Second home, Experiment, Factorial survey, Academics

Introduction

Why people move, and how, is a key issue in population research as it is a crucial driver of changes within a population in a region. It becomes even more important as more complex types of mobility arose in the last decades (e.g. Schneider and Meil 2008; Schneider and Collet 2010; Aybek et al. 2015). Driven by the growing flexibilisation in the labour markets and enhanced transportation structures (Sheller and Urry 2006), one-way migration declined significantly (e.g. Cooke 2013), while short- and long-distance commuting and secondary residences increased (Reuschke 2010; Rüger et al. 2011). Consequently, the different types of circular mobility are frequently discussed as being substitutes for definite relocations (e.g. McHugh 1990; Green et al. 1999; Bell and Ward 2000; Van der Klis and Mulder 2008; Van Ham and Hooimeijer 2009).

Though many authors pointed to the fact that migration decisions are becoming increasingly complex and multidimensional, the significance of mobility types that serve as alternatives to migration is largely neglected (e.g. Halfacree 2004; Clark and Maas 2015; Tabor et al. 2015; Clark and Withers 2017). Only a limited body of literature examines the factors of migration and commuting comparatively. Some of these studies provide sophisticated formal models or elaborated simulations but do not test assumptions empirically (Yapa et al. 1971; Van Ommeren et al. 2000; Schmidt 2014). Other studies use empirical data to identify the push-and-pull factors of migration and commuting in a more explorative way (McHugh 1990; Van der Klis and Mulder 2008; Van Ham and Hooimeijer 2009).

Because of their advantages, experimental designs are increasingly used in migration research (e.g. Hao et al. 2016; Baláž et al. 2016; Baláž and Williams 2017, 2018; Ewers and Shockley 2017). In experiments, different treatments are varied systematically and a greater control over sample selection and allocation is possible as compared to observational studies, which includes classical surveys. This allows for a more detailed investigation of how people weigh conditions when considering migration, while simultaneously making causal inferences.

Originally developed to study beliefs and judgments in social justice (Rossi 1979; Jasso 2006), factorial survey experiments have recently been applied to study decision-making on regional mobility (Abraham and Schönholzer 2009, 2012; Abraham et al. 2010; Abraham and Nisic 2012; Bähr and Abraham 2016; Petzold 2017). However, most of these studies primarily focussed on bargaining strategies of coupled partners when negotiating decisions on migration (Abraham et al. 2010; Bähr and Abraham 2016) or on migration versus commuting (Abraham and Schönholzer 2009, 2012; Abraham and Nisic 2012). However, not much attention is paid to different types of mobility. In particular, daily commuting and establishing a second home have not been distinguished so far (see Petzold 2017).

Applying a factorial survey experiment, this study seeks to contribute to the question on how people make their decisions on three types of regional mobility—migration, daily commuting, and establishing a second home—based on varying job benefits, migration costs, transition costs, and its interactions. For this purpose, hypothetical external job offers were presented to a sample of academic staff of a Swiss university (ETH Zurich). The design allows for a systematic and direct comparison of individuals’ decision-making and intentions regarding the three types of mobility and their drivers. Academics face high geographical mobility requirements (Bauder 2015), and heightened mobility can serve for better employment positions (Morano-Foadi 2005). As compared to other social groups (e.g. long-term unemployed, see Bähr and Abraham 2016), academics are also more likely to belong to a privileged social group that can, in principle, bear high housing and travel costs easier. As transport infrastructure systems are highly developed in Switzerland (cf. Rebmann et al. 2012), all three types of mobility are realistic alternatives, at least for our sample under investigation. In this way, we gain a deeper and more detailed understanding of how people make decisions on regional mobility and shed light on as to what extent different types of mobility are considered as substitutes.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In the subsequent section, we develop a theoretical framework and discuss existing research on mobility decision-making. We outline arguments on which conditions should influence intentions for each mobility alternative. We then describe the construction of our experimental design, the sample used, and the analysis methods applied. After presenting the results, we finally discuss our conclusions and implications for migration research.

Theoretical Framework

In this study, migration implies a permanent relocation of both place of residence and place of work to the new job destination so that only a single residence is used after moving. Commuting is generally defined as regular travelling between home and work and can be distinguished into long-distance commuting and daily commuting (cf. Haas and Osland 2014; Aybek et al. 2015). Long-distance commuters establish a second home near the place of work, from where they travel regularly to their original place of residence, for instance, weekly (cf. Reuschke 2010; Rüger et al. 2011; Weiske et al. 2015). Daily commuters, in contrast, do not set up a second home and so daily travels between the place of work and place of residence are necessary.

Decision-making on three types of spatial mobility

In the long tradition of neoclassical approaches in migration research, moving behaviour can be understood similar to an investment strategy. People weight the costs of migration in relation to the returns to their human capital in certain regions while following a maximisation strategy and, ultimately, opt for or against relocation (e.g. Sjaastad 1962; Speare 1971; Chemers et al. 1978). This basic idea has been transferred to decision-making on different types of mobility by several authors (cf. Alonso 1964; Yapa et al. 1971; Vickerman 1984; Green et al. 1999; Romaní et al. 2003; Abraham et al. 2010; Abraham and Nisic 2012; Huber and Nowotny 2013; Bähr and Abraham 2016; Petzold 2017).

Typically starting from the joint benefits of a potential destination, the potential costs of alternative mobility strategies are weighted against each other in order to determine the utilities of each mobility alternative. Migration bears the costs of establishing a new residence at the place of destination and a total loss of the joint benefits of the current place of residence. Commuting bears the costs of daily transitions over a certain distance. Establishing a second home includes the costs of a new secondary residence in addition to the costs of the main residence as well as regular commuting. If the discounted accumulated benefits exceed the discounted accumulated costs of any mobility alternative, people will become mobile and the mobility alternative with the highest utility will be chosen. Conversely, if accumulated costs of all three mobility types exceed the joint benefits, people will stay where they are (cf. Van Ommeren et al. 2000; Anam et al. 2008; Schmidt 2014; Hao et al. 2016).1

Many authors have emphasised that decision-making on residential mobility has become more complex in the recent years (Halfacree 2004; Haas and Osland 2014; Clark and Maas 2015; Baláž et al. 2016; Clark and Withers 2017; Ewers and Shockley 2017). One strategy to reduce complexity in mobility decision-making is to give priority to dominant factors when determining the utility of a particular strategy. If, for instance, the distance between the current residence and the new workplace region is very short making transition costs quite low, other costs such as suitable housing at the destination do not necessarily need to be considered, and daily commuting is the most likely option. If, in turn, the distance is too long and housing costs at the destination are very low, migration is likely.

Another strategy to deal with complexity involves estimating possible costs and returns at different stages in decision-making (e.g. Tversky and Kahneman 1974). Consistent with the models of stepwise decision-making on spatial mobility (e.g. Yapa et al. 1971; Vickerman 1984; Eliasson et al. 2003), it can be assumed that not all mobility alternatives are compared at all points of the utility function. Since a second home always bears additional costs, it is very likely that people will first evaluate the utilities of migration and commuting. If certain costs of migration or commuting are not dominant but equally high so that both alternatives yield nearly equal utilities, establishing a second home will come into the set of potential mobility alternatives and people will start to consider it as an alternative.

More importantly, potential irreversible costs of migration, such as the final loss of the current place of residence, can be rated higher than gains in utility (cf. Williams and Baláž 2012). In their concept of loss aversion, Kahneman and Tversky (1984) argued that the attractiveness of a possible gain is not sufficient to compensate for a possible loss, even given equal stakes. Transferred to decisions on alternative types of spatial mobility, this means people will avoid losses with disruptive long-distance migrations, especially when the current residence is very highly valued (cf. Kley 2011). In a situation where daily commuting is impossible due to the distance, peoples’ aversion to the loss of the current residence can then result in a preference for the second home because its overall utility exceeds the overall utilities of migration and commuting.

Hypotheses

Recent studies have shown that residential changes are mainly triggered by job characteristics (Niedomysl and Hansen 2010; Scott 2010). Job benefits may include the wage, the formal position, or interesting tasks involved. We assume that all types of mobility are positively associated with the achievement of subjective life goals by taking a beneficial job. As job benefits can be realised irrespective of a specific type of mobility, we do not make any assumptions about how these benefits are related to a preference for a particular mobility type.2 Either way, the perceived joint benefits need to exceed the costs of moving. We, therefore, focus on the role of costs of migration from the current place of residence (i) to the place of work (j) and the role of costs of regular transition between both locations in the formation of specific mobility intentions.

Migration costs (Cmig(i, j)) are composed by both the potential loss of the current residence and housing costs that arise at the new place of living. Any assets that are rated higher at the current residential location in comparison with anywhere else that can hardly be transferred to another region reflect location-specific capital and, consequently, the costs of migration (cf. DaVanzo 1981). Typical sources of location-specific capital are one’s own and the partner’s local employment (e.g. Eliasson et al. 2003), property ownership (e.g. Helderman et al. 2006), and social relations (e.g. Mulder and Wagner 2012). Consistently, the respective job-related, housing, and societal offers in the workplace region also constitute potential migration costs. Transition costs (Ctrans(i, j)) include the costs of regular transitions between both places. They are constituted by the travel distance and the frequency with which this distance must be travelled so that they culminate in an overall journey time.

Given a sufficient joint benefit, the intention to migrate (Imig(i, j)) will be affected by migration costs, particularly by the potential loss of the current residence and by the emerging transition costs. We assume that the lower the migration costs and the higher the transition costs, the stronger will be the intention for migration (hypothesis 1).

Contrarily, migration costs do not occur when people commute between both places every day (Icom(i, j)). Accordingly, costs of regular travelling should be particularly significant and a short distance is essential. We do expect that if the commuting intention is stronger, the lower are the transition costs and the higher are the migration costs (hypothesis 2).

As outlined previously, establishing a second home at the place of work (Isec(i, j)) can become an attractive alternative, in particular under the conditions of prohibitively high migration costs caused by location-specific capital and high transition costs caused by a long distance. By establishing a secondary home, the migration costs can be reduced by the component of the total loss of the current location-specific capital and transition costs can be reduced by the component of daily travels over the distance. Hence, a second home can yield the highest subjective utility through the aversion against extraordinary migration and transition costs.

Accordingly, we expect that the higher the transition and the migration costs, the stronger will be the intention to establish a second home. In addition to these additive effects, we also assume effects of interaction between migration and transition costs. The intention for a second home will be particularly affected when high migration costs and transition costs are present at the same time (hypothesis 3).

Method and Data

Studies on regional mobility and migration typically apply survey and register data (e.g. Green et al. 1999; Van Ommeren et al. 1999; Van Ham and Hooimeijer 2009; Rüger et al. 2011; Sandow and Westin 2010), which bears substantial shortcomings. First, variable operationalisation often forces coding information about moving factors into rough and approximate categories, regularly limited to the socio-economic background. Second, mobility intentions and mobility decisions are to be investigated afterwards by group comparison between those who decided to commute with those who decided to relocate (e.g. Romaní et al. 2003; Eliasson et al. 2003). It is not clear, then, to what extent different types of mobility were actually perceived as alternatives or even substitutes. Third, not all mobility intentions are transferred into mobility behaviour and, in turn, not all factors and considerations are reported afterwards by respondents (e.g. Huber and Nowotny 2013). Accordingly, it is problematic to use mobility behaviour to examine how people make their decisions to move (cf. Coulter and Scott 2015). Fourth, problems of endogeneity emerge from the processes of systematic self-selection into different mobility groups, which are hard to capture statistically by ex-post analysis due to unobserved heterogeneity (cf. Haas and Osland 2014).

In contrast, we tested our hypotheses using a factorial survey experiment among a sample of Swiss academics who were presented hypothetical job offers in order to measure their mobility intentions.3 Academics are focused because of the high geographical mobility requirements in the academic system (Bauder 2015), where heightened mobility can serve for better employment positions (Morano-Foadi 2005). Concurrently, Switzerland is a country with highly developed transport infrastructure systems where all three types of mobility are realistic alternatives. In particular, job-related commuting across municipalities increased constantly and the average distances grew substantially over the years (Guth et al. 2011). Furthermore, journeys with overnight stays increased and constituted approximately one-third of all journeys per person per year in 2015. Ten per cent of all journeys with overnight stays are job-related and even include international destinations (Rebmann et al. 2012, Perret et al. 2017). Nevertheless, both internal migration and international migration remained mainly stable among the Swiss population in the last decades (Bundesamt für Statistik 2018a, b).

Factorial survey design

The factorial survey method is an experimental design that allows for the variation of different costs and benefits in hypothetical decision situations (Jasso 2006; Mutz 2011; Auspurg and Hinz 2015). In the situations described (vignettes), i.e. job offers, treatments (dimensions) are varied systematically and randomly assigned to respondents. Both variation and randomisation serve to estimate isolated treatment effects. Since survey experiments combine advantages of experiments with those of surveys, they are widely applied in the social sciences (cf. Wallander 2009) as well as increasingly used in migration research (Abraham and Schönholzer 2009, 2012; Abraham et al. 2010; Abraham and Nisic 2012; Bähr and Abraham 2016; Petzold 2017).

The first advantage for the present study is that the subjects do not have to be confronted with real job offers, which permits the construction of job descriptions with uncorrelated features, even if they would be rare in reality. Second, the situation involving a realistic decision is simulated through the numerous dimensions, the relative importance of which has to be weighed against each other by the respondents. Third, the intentions of single individuals for all three types of regional mobility can be measured with regard to the same conditions as presented in the vignette. In contrast to the existing survey studies, we do not simply compare people from different mobility groups after their final mobility choices.

Despite some shortcomings, such as potential illogical cases or order effects (Auspurg and Jäckle 2017), the design serves for high internal validity if the vignettes are not overly complex and a limited number of vignettes is used per respondent (Sauer et al. 2011). The major criticism associated with vignette studies is that both treatments presented and intentions reported are only hypothetical. Hence, the results cannot be generalised to real behaviour. However, studies validating vignette judgments against true behaviour indicate that, in principle, reality-based decisions are considered the most, at least regarding the direction and relative strength of treatment effects (e.g. Eifler 2010; Hainmueller et al. 2015; Petzold and Wolbring 2019).

Table 1 shows the varied dimensions that address the theoretically distinguished vectors of job benefits, migration costs, and transition costs. To provide an appropriate amount of information, nine dimensions were chosen (cf. Auspurg and Hinz 2015). Additionally, one’s own and partner’s incomes and career prospects, temporality of contracts, distance and travel time, and housing prospects have also been varied as treatments in previous studies (Abraham and Schönholzer 2009, 2012; Abraham et al. 2010; Abraham and Nisic 2012; Bähr and Abraham 2016; Petzold 2017).

Table 1.

Vignette dimensions and levels

| Vignette dimensions | Levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Temporary contract | Temporary | Tenured | |

| Income change | Less income | Equal income | Higher income |

| Job content | Less interesting | Equally int. | More interesting |

| Formal position | Lower status | Equal status | Higher status |

| Presence flexibility | Fix | Flexible | |

| Distance (h) | 2 h 30 min | 1 h 30 min | 45 min |

| Region | Europe, non-German | Europe, German | Switzerland |

| Suitable housing prospects | Worse | Average | High |

| Spouse job chances | Lower | Equal | higher |

The Cartesian product of all dimensions and levels results in a vignette universe of 8748 possible combinations,4 wherein all treatments are perfectly balanced and uncorrelated. We draw a D-efficient sample of 150 vignettes out of the vignette universe using the modified Federov search algorithm (D-efficiency = 97.69), which provides the optimal solution between a maximum zero-correlation of the dimensions (orthogonality) and maximum balanced levels (see Kuhfeld et al. 1994; Atzmüller and Steiner 2010; Dülmer 2016). The sampled vignettes were systematically distributed to 15 decks with ten vignettes each. The decks were randomly assigned to respondents whose were presented the ten vignettes in a random order to neutralise learning and fatigue effects. Due to the advantages in terms of recruitment, randomisation, and presentation, the design was implemented in an online survey (CAWI). As intended, all vignette dimensions are very well balanced (Appendix Table 3) and nearly zero-correlated (Appendix Table 4) in the final data base.

Table 3.

Frequencies of vignette dimensions

| Vignette dimensions | N | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Temporary contract | ||

| Temporary | 2815 | 49.85 |

| Tenured | 2832 | 50.15 |

| Income change | ||

| Less income | 1848 | 32.73 |

| Equal income | 1900 | 33.65 |

| Higher income | 1899 | 33.63 |

| Job content | ||

| Less interesting | 1937 | 34.30 |

| Equally interesting | 1937 | 34.30 |

| More interesting | 1773 | 31.40 |

| Formal position | ||

| Lower status | 1980 | 35.06 |

| Equal status | 1858 | 32.90 |

| Higher status | 1809 | 32.03 |

| Presence flexibility | ||

| Fix | 2799 | 49.57 |

| Flexible | 2848 | 50.43 |

| Distance (h) | ||

| 2 h 30 min | 1860 | 32.94 |

| 1 h 30 min | 1834 | 32.48 |

| 45 min | 1953 | 34.58 |

| Region | ||

| Europe, non-German | 1804 | 31.95 |

| Europe, German | 1920 | 34.00 |

| Switzerland | 1923 | 34.05 |

| Suitable housing prospects | ||

| Bad | 1895 | 33.56 |

| Average | 1927 | 34.12 |

| Good | 1825 | 32.32 |

| Spouse job prospects | ||

| Worse | 1841 | 32.60 |

| Equal | 1954 | 34.60 |

| Good | 1852 | 32.80 |

| Total | 5647 | 100 |

Table 4.

Correlations between vignette dimensions

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Temporary | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| 2 Income | 0.0115 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| 3 Position | 0.0111 | 0.0148 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| 4 Content | − 0.0091 | − 0.0017 | 0.0037 | 1.0000 | |||||

| 5 Housing | 0.0275 | 0.0085 | 0.0048 | − 0.0024 | 1.0000 | ||||

| 6 Region | 0.0158 | 0.0214 | 0.0052 | − 0.0419 | 0.0031 | 1.0000 | |||

| 7 Presence | 0.0033 | − 0.0099 | 0.0075 | 0.0235 | 0.0049 | − 0.0161 | 1.0000 | ||

| 8 Distance | − 0.0050 | − 0.0053 | 0.0007 | 0.0297 | 0.0112 | 0.0003 | 0.0082 | 1.0000 | |

| 9 Job partner | 0.0037 | − 0.0086 | 0.0137 | 0.0014 | − 0.0135 | − 0.0041 | − 0.0077 | 0.0098 | 1.0000 |

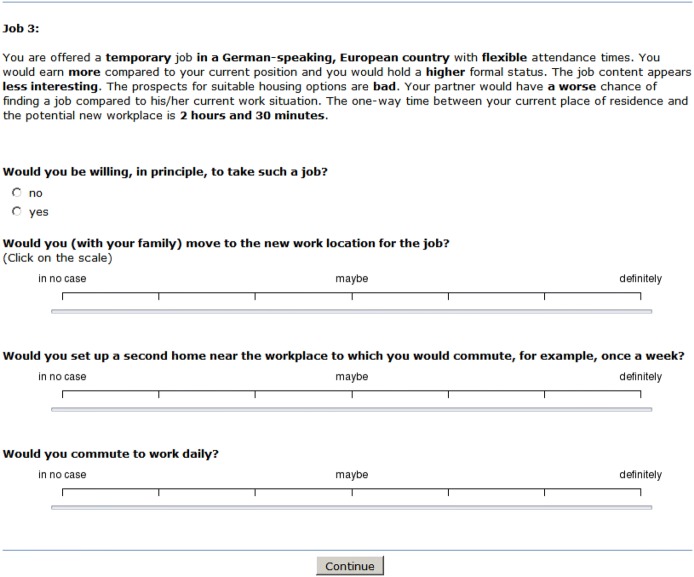

Figure 1 shows the example of a vignette with the description of the job offered. The first subsequent question measures the general willingness to accept the job (‘yes’ (0)/‘no’ (1)). Then, the intentions for migration, establishing a second home and daily commuting were reported by the respondents on a 7-point scale from ‘in no case’ (1) to ‘definitely’ (7), while no values were specified previously.

Fig. 1.

Vignette example

Sample

Data were collected in summer 2013. The academic staff of ETH Zurich, i.e. professors, lecturers, doctoral students, and postdoctoral researchers, was once invited via e-mail (N = 9406) without a reminder for policy reasons of the university. 1178 began answering the questionnaire (12.5% response rate), and 827 of the completed responses could be used after data cleaning (8.8% completion rate). As vignettes consist of labour market prospects for one’s partner, only respondents who declared to have a partner were included in the analyses.5 In sum, a total of 5647 hypothetical job offers assessed by 582 academics constitute the database.6

The composition of the sample is shown in Table 2. The participants are on average 36.34 years old and predominantly male. Most participants are from the natural sciences and engineering fields, followed by economics and social sciences. All career stages are represented. A large share of nearly three-quarters of non-tenured positions is typical for the Swiss higher education system. The vast majority lives in dual earner households. Although the right column of Table 2 indicates that the sample composition largely corresponds to the profile of the ETH Zurich, it cannot be claimed to be representative for a certain population, and the external validity of the experiment will be debated below. However, the priority lies in high internal validity, which is served by the experimental design so that the sample composition does not distort effect estimation.

Table 2.

Socio-economic and professional characteristics of the sample

| N | Range | M/percent (%) | SD | Target population (percent, %)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 582 | 24–68 | 36.34 | 9.33 | – |

| Sex | 0–1 | ||||

| Female | 227 | 39.0 | 31.6 | ||

| Male | 355 | 61.0 | 68.4 | ||

| Income | 0–1 | ||||

| < 3000 CHF | 22 | 3.8 | – | ||

| 3000–3999 CHF | 121 | 20.8 | – | ||

| 4000–4999 CHF | 83 | 14.2 | – | ||

| 5000–5999 CHF | 86 | 14.8 | – | ||

| 6000–6999 CHF | 79 | 13.6 | – | ||

| 7000–7999 CHF | 45 | 7.7 | – | ||

| 8000–8999 CHF | 29 | 5.0 | – | ||

| 9000–9999 CHF | 24 | 4.1 | – | ||

| 10,000–11,999 CHF | 39 | 6.7 | – | ||

| 12,000–13,999 CHF | 15 | 2.6 | – | ||

| 14,000–15,999 CHF | 12 | 2.0 | – | ||

| > 16,000 CHF | 27 | 4.7 | – | ||

| Discipline | 0–1 | ||||

| Architecture | 16 | 2.8 | 11.8 | ||

| Economics | 24 | 4.1 | 3.5 | ||

| Natural sciences | 308 | 52.9 | 47.3 | ||

| Engineerings | 131 | 22.5 | 24.1 | ||

| Social sciences | 42 | 7.2 | 2.8 | ||

| Cultural sciences | 8 | 1.4 | | | ||

| Educational sciences | 10 | 1.7 | | | ||

| Human sciences | 5 | 0.9 | | | ||

| Music and arts | 4 | 0.7 | | | ||

| Management | 3 | 0.5 | | | ||

| History and religion | 3 | 0.5 | 2.8 | ||

| Other | 28 | 4.8 | 7.7 | ||

| Position | 0–1 | ||||

| Full professor | 74 | 12.7 | 7.0 | ||

| Associate professor | 18 | 3.1 | | | ||

| Assistant professor | 60 | 10.3 | 1.4 | ||

| Postdoctoral researcher | 112 | 19.2 | | | ||

| PhD student | 222 | 38.1 | | | ||

| Research assistant | 95 | 16.3 | 88.6 | ||

| Teaching assistant | 1 | 0.2 | 2.9 | ||

| Current position temporary | 429 | 0–1 | 73.7 | – | |

| Children in household | 215 | 0–1 | 36.9 | – | |

| Property ownership | 118 | 0–1 | 20.3 | – | |

| Spouse with own job | 516 | 0–1 | 88.7 | – |

Source: Own calculations, *www.ethz.ch/services/de/finanzen-und-controlling/zahlen-und-fakten/personal.html (28.8.2018)

In addition to the vignette dimensions, the partner’s employment, property ownership, and the current job tenure are included in the analysis for theoretical reasons. Furthermore, age, sex, position, discipline, income group, and children in the household will serve as covariates for the randomisation check.

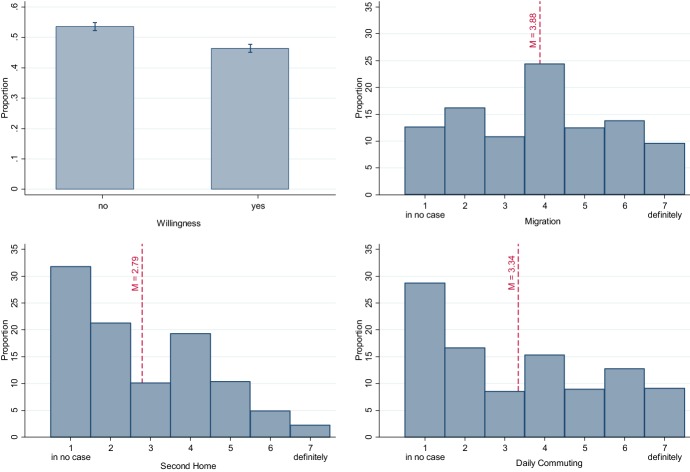

Outcomes

Vignettes were rated with regard to the overall willingness to compete for the job as well as regarding the three intentions to move. As can be seen from Fig. 2, migration is intended the strongest across all vignettes (M = 3.88; SD = 1.84), while daily commuting is less intended (M = 3.34; SD = 2.07). The intention to establish a second home is preferred the lowest across all job offers (M = 2.79; SD = 1.69). Establishing a second home seems to be generally least attractive, which supports our idea that it comes primarily into play only under specific conditions.

Fig. 2.

Distributions of willingness to compete for the job and of the mobility intentions

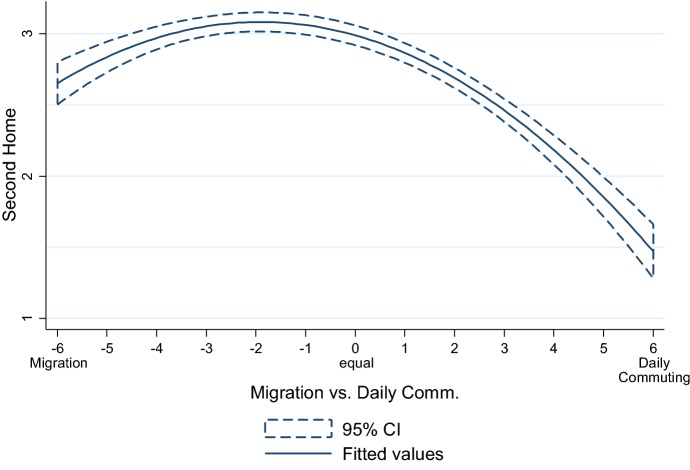

The migration intention correlates negatively with the intention for daily commuting (r = − 0.24; p = 0.000) and positively with the intention for a second home (r = 0.12; p = 0.000). The second home intention is also negatively related to the intention for daily commuting (r = − 0.12; p = 0.000). To explore the relation between the three mobility scales more comprehensively, we fitted the intention for a second home with a quadratic term across the difference between the intentions for migration and commuting (Fig. 3). The difference scale ranges from − 6 to 6, where the minimum represents a clear preference for migration over commuting and the maximum represents a clear preference of commuting over migration. Consistently, the value 0 represents that there is not any difference and neither migration nor daily commuting is clearly preferred.

Fig. 3.

Second home intention across the difference between migration vs. commuting intention (fitted values)

If either one-way migration or daily commuting is exclusively preferred, the second home intention is the weakest. In turn, if there is less difference in intentions for commuting and migration, the second home intention is the strongest. This inverted U-shaped relationship between the intention to establish a second home and the difference between the intentions to migrate and commute indicates that a second home seems to be most attractive when the respondents are irresolute with regard to the question whether to migrate or to commute, given the presented vignette dimensions.

Estimation method

Furthermore, Fig. 2 also presents that respondents would compete for only slightly less than half of all hypothetical job offers (2620; 46.4%). From a theoretical point of view, one may expect that respondents would only express intentions to become mobile if they are willing to accept the job presented. While this is the case for some vignettes, mobility intentions were measured though respondents are not willing to take the job for some others. It seems that some respondents made their decisions on job attractiveness and on regional mobility rather sequentially, while the decisions were rather simultaneous for some others (cf. Romaní et al. 2003).

This leads to left-censored data, as no observations of the mobility intentions are expressed for some vignettes. In addition, the correlations between the willingness to compete for the job and the intention to migrate (r = 0.40; p = 0.000), the intention for daily commuting (r = 0.18; p = 0.000), and the intention for a second home (r = 0.16; p = 0.000) reflect positive dependencies even though mobility intentions are not fully determined by job attractiveness. Since we cannot rule out that unobserved determinants influence both the willingness to compete for the job and the mobility intentions, the issue can be treated as a problem of selection bias.

To capture this potential bias, we estimate Heckman selection models that explicitly consider unobserved confounders between a certain group status and the dependent variable (Heckman 1979). The estimated probability of respondents’ willingness to compete for a presented job for each single vignette is used as an additional explanatory variable to correct for potential selection bias in regression models on mobility intentions. We will only discuss the results of the corrected linear regressions at the second stage. As compared to common hurdle models such as Tobit or Craggit, using the Heckman correction allows to include vignettes for which mobility intentions are measured even if respondents would reject the job. As compared to non-corrected ordinary least squares regressions (OLS), the selection of the willingness to take the job is not ignored. This analyses strategy helps, at best, to keep up the underlying experimental design as no vignettes are to be excluded.7

Moreover, as each participant assessed several job offers, the data structure is hierarchical (Jasso 2006; Auspurg and Hinz 2015). To avoid any underestimated standard errors at the person’s level and overestimated standard errors at the vignette level resulting from non-modelled heteroscedasticity, we use standard errors clustered by the respondents in all models (heteroscedasticity-consistent ‘sandwich’ standard errors by Huber-White).8

Results

As argued above, the migration intention should be mainly driven by migration costs and the intention to commute everyday should be mainly driven by transition costs. However, our core argument is that establishing a second home can become an attractive alternative especially when migration subjectively bears intolerable costs and the distance is too long for daily commuting. On the one hand, the total loss of the current place of residence can be avoided by establishing a second home. On the other hand, a second home can diminish transition costs by decreasing the frequency of commuting. This would have to be reflected both by additive main effects of cost indicators on mobility intentions, and by interaction effects between migration costs and transition costs on the intention for a second home.

First, the effects of transition costs and migration costs as indicated by vignettes’ and respondents’ characteristics on the reported mobility intentions were estimated. Second, we included multiplicative terms of the indicators for migration costs and the distance as the major indicator for transition costs to test for expected effects of interactions. Indicators of the job benefits are current and offered job tenure as well as changes in income, formal position and job content. Migration costs are indicated by housing prospects, existing property ownership and partner’s job chances and current job situation. Transition costs have been varied according to distance between both locations, measured by travel time, according to presence requirements and according to the crossing of national borders.9

Estimation weights of factors on mobility intentions

Figure 4 shows the results of estimations for main effects on all three mobility intentions. As assumed in hypothesis 1, a lack of home ownership and a partner without employment are remarkable predictors of the intention to migrate (Model 1). Accordingly, the partner’s good job prospects also endorse the intention. Additionally, there are also positive effects of adequate housing opportunities, albeit comparatively small. In turn, a short travel distance is a major obstacle. The results support hypothesis 1: The lower the migration costs and the higher the transition costs, the stronger is the intention to migrate.

As expected in hypothesis 2, the intention for daily commuting is ultimately encouraged by transition costs, in particular by a short travel distance (Model 3). For a travel time of 45 min, as compared to 2.30 h, daily commuting is on average favoured by nearly three points on the rating scale. In addition, most migration costs affect the intention to commute in a slightly positive manner. Hypothesis 2 is largely confirmed: The commuting intention is the stronger, the lower the transition costs and the higher the migration costs are (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Heckman-corrected regression models on mobility intentions

We argued that a second home can become an alternative to migration as it allows for maintaining the current place of residence as well as an alternative to daily commuting as it avoids unbearable travel costs. In hypotheses 3, we accordingly proposed that the second home intention should be driven in an additive way by high migration costs, just as daily commuting, and high transition costs, just as migration. Results of Model 2 reveal that the transition costs indeed show effects with directions similar to its effects on the migration intention. In turn, the migration costs show effects with directions similar to its effects on the commuting intention. If the partner is currently unemployed and his or her job prospects are equal or higher at the destination, the intention for a second home is slightly weaker. This implies that if the partner is employed and his or her job prospects are worse, the intention for a second home is relatively stronger. If, with 45 min, the distance is very short and the job is located in Switzerland, the second home intention is also low. This means that with a longer distance and a location outside of Switzerland, the intention for a second home is relative to the lower cost conditions quite strongly. In sum, these results support the additive cost effects as assumed in hypothesis 3: The higher the transition and migration costs, the stronger is the intention to establish a second home.

Interactions between migration and transition costs on the intention to establish a second home

We test the assumption that the second home alternative comes, especially into play when both migration costs and transition costs seem unacceptably high. For this purpose, we included interaction terms of the distance with all the indicators for migration costs, i.e. property ownership, housing prospects, partner’s current employment status, and their job chances at the destination. Again, models for all three mobility intentions are estimated. For a simplified interpretation, predicted values are reported for each interaction model, while effect coefficients can be found in Tables 10, 11, 12, and 13 in Appendix.

Table 10.

Interaction of property ownership and distance on mobility intentions

| Migration | Second home | Daily commuting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| No property owner (ref. yes) | 0.746** | (0.250) | − 0.345 | (0.232) | − 0.577** | (0.189) |

| Distance 1 h 30 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | − 0.282 | (0.186) | − 0.047 | (0.179) | 1.076*** | (0.207) |

| Distance 45 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | − 0.980*** | (0.182) | − 1.236*** | (0.193) | 2.752*** | (0.235) |

| Property ownership × distance | ||||||

| No property × 1 h 30 min | − 0.169 | (0.199) | 0.020 | (0.193) | 0.049 | (0.223) |

| No Property × 45 min | − 0.136 | (0.195) | 0.482* | (0.206) | 0.238 | (0.249) |

| Nvignettes | 5647 | 5647 | 5647 | |||

| Ncensored | 1888 | 1911 | 1902 | |||

| Nuncensored | 3759 | 3736 | 3745 | |||

| Nrespondents | 582 | 582 | 582 | |||

| Rho | − 0.594 | − 0.489 | − 0.323 | |||

| Sigma | 1.587 | 1.631 | 1.603 | |||

| Lambda | − 0.942 | − 0.799 | − 0.519 | |||

| Wald Chi2 | 817*** | 344*** | 1541*** | |||

Heckman-corrected regressions; clustered standard errors in parentheses +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; covariates: all vignette dimensions, respondents’ characteristics

Table 11.

Interaction of suitable housing and distance on mobility intentions

| Migration | Second home | Daily commuting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Suitable housing average (ref. worse) | 0.337* | (0.140) | − 0.253* | (0.128) | − 0.100 | (0.104) |

| Suitable housing high (ref. worse) | 0.529*** | (0.128) | − 0.140 | (0.130) | − 0.279** | (0.098) |

| Distance 1 h 30 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | − 0.400** | (0.137) | − 0.237+ | (0.130) | 1.105*** | (0.131) |

| Distance 45 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | − 0.967*** | (0.141) | − 0.945*** | (0.131) | 2.859*** | (0.131) |

| Suitable housing × distance | ||||||

| Suitable housing average × 1 h 30 min | − 0.060 | (0.173) | 0.355* | (0.173) | − 0.078 | (0.160) |

| Suitable housing average × 45 min | − 0.187 | (0.193) | 0.222 | (0.177) | 0.115 | (0.163) |

| Suitable housing high × 1 h 30 min | − 0.005 | (0.177) | 0.256 | (0.185) | 0.115 | (0.173) |

| Suitable housing high × 45 min | − 0.189 | (0.160) | 0.109 | (0.161) | 0.171 | (0.143) |

| Nvignettes | 5647 | 5647 | 5647 | |||

| Ncensored | 1888 | 1911 | 1902 | |||

| Nuncensored | 3759 | 3736 | 3745 | |||

| Nrespondents | 582 | 582 | 582 | |||

| Rho | − 0.594 | − 0.489 | − 0.323 | |||

| Sigma | 1.587 | 1.631 | 1.603 | |||

| Lambda | − 0.943 | − 0.799 | − 0.519 | |||

| Wald Chi2 | 848*** | 335*** | 1541*** | |||

Heckman-corrected regressions; clustered standard errors in parentheses +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; covariates: all vignette dimensions, respondents’ characteristics

Table 12.

Interaction of job of spouse and distance on mobility intentions

| Migration | Second home | Daily commuting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Spouse no job (current) (ref. yes) | 0.706** | (0.260) | − 0.331 | (0.249) | 0.623* | (0.279) |

| Distance 1 h 30 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | − 0.414*** | (0.076) | − 0.033 | (0.079) | 1.177*** | (0.081) |

| Distance 45 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | − 1.077*** | (0.078) | − 0.832*** | (0.082) | 3.034*** | (0.087) |

| Spouse job × distance | ||||||

| Spouse no job × 1 h 30 min | − 0.115 | (0.217) | 0.083 | (0.211) | − 0.548+ | (0.223) |

| Spouse no job × 45 min | − 0.189 | (0.216) | 0.049 | (0.194) | − 0.760+ | (0.249) |

| Nvignettes | 5647 | 5647 | 5647 | |||

| Ncensored | 1888 | 1911 | 1902 | |||

| Nuncensored | 3759 | 3736 | 3745 | |||

| Nrespondents | 582 | 582 | 582 | |||

| Rho | − 0.594 | − 0.489 | − 0.323 | |||

| Sigma | 1.587 | 1.633 | 1.600 | |||

| Lambda | − 0.942 | − 0.798 | − 0.517 | |||

| Wald Chi2 | 815*** | 339*** | 1572*** | |||

Heckman-corrected regressions; clustered standard errors in parentheses +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; covariates: all vignette dimensions, respondents’ characteristics

Table 13.

Interaction of job chances of spouse and distance on mobility intentions

| Migration | Second home | Daily commuting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Spouse job chance equal (ref. lower) | 0.711*** | (0.129) | − 0.154 | (0.142) | − 0.462*** | (0.112) |

| Spouse job chance higher (ref. lower) | 0.927*** | (0.128) | − 0.332** | (0.127) | − 0.305** | (0.109) |

| Distance 1 h 30 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | − 0.399*** | (0.125) | − 0.044 | (0.132) | 0.812*** | (0.129) |

| Distance 45 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | − 1.173*** | (0.130) | − 0.846*** | (0.133) | 2.885*** | (0.137) |

| Spouse job chance × distance | ||||||

| Spouse job chance equal × 1 h 30 min | − 0.044 | (0.182) | − 0.117 | (0.196) | 0.641*** | (0.187) |

| Spouse job chance equal × 45 min | − 0.133 | (0.189) | − 0.097 | (0.201) | 0.258 | (0.176) |

| Spouse job chance higher × 1 h 30 min | − 0.031 | (0.155) | 0.174 | (0.171) | 0.227 | (0.163) |

| Spouse job chance higher × 45 min | − 0.987 | (0.161) | 0.153 | (0.175) | − 0.075 | (0.167) |

| Nvignettes | 5647 | 5647 | 5647 | |||

| Ncensored | 1888 | 1911 | 1902 | |||

| Nuncensored | 3759 | 3736 | 3745 | |||

| Nrespondents | 582 | 582 | 582 | |||

| Rho | − 0.594 | − 0.489 | − 0.323 | |||

| Sigma | 1.587 | 1.631 | 1.603 | |||

| Lambda | − 0.943 | − 0.799 | − 0.519 | |||

| Wald Chi2 | 829*** | 343*** | 1553*** | |||

Heckman-corrected regressions; clustered standard errors in parentheses +p < 0.10, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; covariates: all vignette dimensions, respondents’ characteristics

The predicted values for all three mobility intentions under the combined conditions of distance and property ownership are plotted in Fig. 5. Given a distance of 2.30 h, home owners clearly prefer daily commuting and a second home as compared to non-owners who, in turn, show a stronger inclination for migration. This difference pattern holds also true under the distance condition of 1.30 h. It is only different under the 45 min condition, where no substantial differences between home owners and non-owners exist in the intention to establish a second home. Accordingly, long commuting distance increases the intention to establish a second home compared to a short distance markedly, especially among home owners. This increase is by almost one-half scale points larger among home owners as among respondents without their own properties and is significant at the 5% level (see Appendix Table 10). By contrast, no significant interaction effect has been found for the migration intention and the intention for daily commuting. These results confirm our assumption that the alternative of a second home is particularly attractive when the irreversible loss of the current residence is weighted to be comparatively costly, i.e. by home owners.

Fig. 5.

Interaction of property ownership and distance on mobility intentions (predicted values)

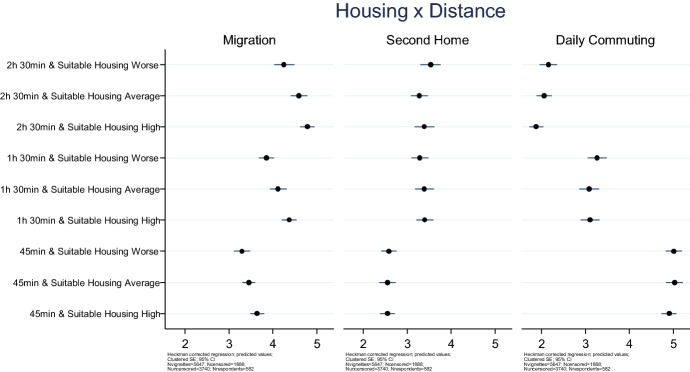

Figure 6 contains the predicted values of the mobility intentions over the three distance levels in the interaction with suitable housing prospects at the region of destination. As compared to average or good housing prospects, worse housing prospects go along with slightly stronger second home and daily commuting intentions and a weaker intention for migration under the 2.30-h condition. While this pattern is stable for migration and daily commuting as well in the 1.30-h condition, it changed for the second home intention. With worse housing prospects, the intention to establish a second home increases from 1.30 h to 2.30 h distance. With average housing prospects, a 2.30-h distance slightly decreases the intention for a second home relative to 1.30-h distance. This effect difference is about one-third scale point, rather small but statistically significant at the 5% level (see Appendix Table 11). Once again, higher costs in both distance and housing prospects slightly increase the second home intention.

Fig. 6.

Interaction of suitable housing and distance on mobility intentions (predicted values)

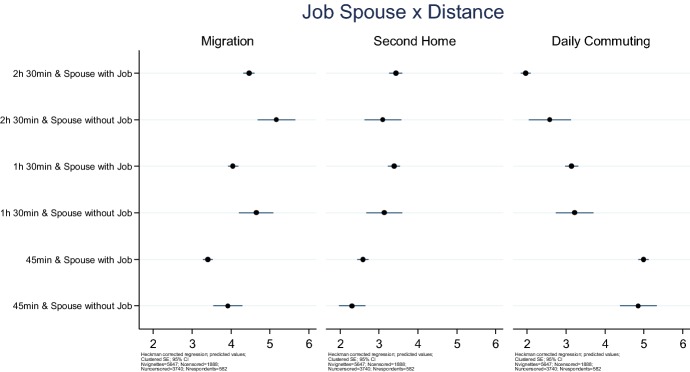

The predicted values of the mobility intentions over all the distance levels for respondents with and without currently employed partner are shown in Fig. 7. When the distance is 2.30 h, those with an employed partner report weaker intentions for migration and for daily commuting but are more inclined to establish a second home, compared to those with unemployed partners, when the distance is 1.30 h or 2.30 h. With a decreasing distance, the difference in the intention for daily commuting between respondents with and without employed partners disappears. This interaction between the distance and the partner’s employment status on the daily commuting intention is significant at the 10% level (see Appendix Table 12).

Fig. 7.

Interaction of job of spouse and distance on mobility intentions (predicted values)

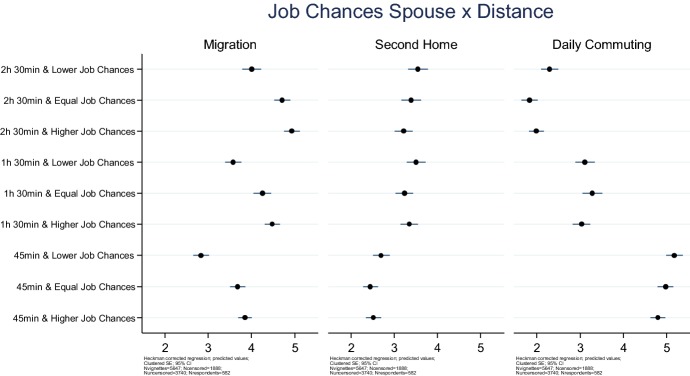

As finally shown in Fig. 8, once again, there is no significant interaction effect in the model on the intention to establish a second home. Instead, as in the interaction with partner’s current employment status, there is a significant interaction in the model for daily commuting (see Appendix Table 13). A reduction in the distance from 2.30 h to 1.30 h increases the intention for daily commuting even more if the partner’s job opportunities are equal as compared to if the partner’s job opportunities are low. This is to say that daily commuting is more preferred with lower job chances than with equal or higher job opportunities when the distance is 2.30 h and comparatively less preferred when the distance is 1.30 h. However, in line with our argumentation, costs show additive effects. The predicted values in the intention to establish a second home are highest when the distance is long and partner’s job opportunities are low. The intention for migration is, in contrast, significantly lower with low job opportunities.

Fig. 8.

Interaction of job chances of spouse and distance on mobility intentions (predicted values)

Discussion and Conclusions

Increasing labour market flexibility accompanied by improved transportation structures promote more complex forms of regional mobility such as daily commuting and weekly travels between the place of origin and a second home. In this wake, it is frequently argued that the types of circular mobility are substituting for one-way migration (McHugh 1990; Green et al. 1999; Bell and Ward 2000; Van der Klis and Mulder 2008; Van Ham and Hooimeijer 2009; Cooke 2013) and that mobility decisions have become more complex and multidimensional in the recent past (e.g. Halfacree 2004; Clark and Maas 2015; Tabor et al. 2015; Clark and Withers 2017). However, most existing studies in this field suffer from data restrictions since usually the observed characteristics of people who have already decided or intended to migrate or to commute are compared (e.g. Romaní et al. 2003; Eliasson et al. 2003; Huber and Nowotny 2013). This raises problems of endogeneity and lack of information regarding complex decision situations as well as about counterfactual conditions. It remains also open to what extent different types of mobility were considered as being alternatives.

Contrarily, decision-making on migration, commuting, and establishing a secondary home was investigated in this study, while considering complexity through treatment variation and fixing endogeneity problems. In line with the growing number of insightful experiments in migration research (Abraham et al. 2010; Bähr and Abraham 2016; Baláž et al. 2016; Baláž and Williams 2017, 2018; Ewers and Shockley 2017), we conducted a factorial survey experiment that combines the advantages of an experiment with the advantages of a survey (cf. Auspurg and Hinz 2015). Hypothetical job offers with varying conditions were randomly assigned and presented to a sample of academic staff of a Swiss university (ETH Zurich). This serves for unbiased estimations of the relative decision weights attributed to the various factors and its interactions. We measured the intentions to migrate, to commute, and to establish a second home for each job offer, which allows for a systematic and direct comparison.

We argued that it is likely that people will first evaluate whether certain conditions are dominant in a situation to facilitate migration or commuting. If the distance is very short, daily commuting will be likely. If the distance is very long for daily commuting but conditions allow for a convenient relocation, migration will be likely. Consistently, establishing a secondary home will not be an alternative in this situation. In contrast, when the distance is very long and the costs of relocation are valued intolerably high, the second home alternative will come into play, provided economic resources are sufficiently high. Referring to the concept of loss aversion, the total loss of the current residence can be valued subjectively higher than additional housing costs at the place of work. Hence, the utility of a second home can exceed the joint utilities of migration and commuting particularly in this high-cost situation. A second home can reduce migration costs by the avoidance of the loss of the current residence and transition costs by a lower frequency of commuting.

Our results show that if there is a short travel time between both locations, daily commuting is clearly preferred. In turn, if there are good conditions at the new location, low location-specific capital at the current residence, and high travel costs in terms of time and money, migration is more strongly intended. Indeed, establishing a secondary home is more intended when migration costs are high, just as with daily commuting, and transition costs are high, just as with migration. Under these conditions, a second home seems to be perceived as an alternative to both migration and daily commuting.

Interaction analyses revealed that home owners are significantly more inclined to establish a secondary home than non-owners when the distance is 2.30 h. Moreover, worse housing prospects increase the second home intention when the distance switches from 1.30 h to 2.30 h, while average housing prospects somewhat reduce this. A currently employed partner makes respondents more willing to establish a second home, as compared to those without employed partners, when the distance is 1.30 h or 2.30 h. Yet, these effects are additive. An interaction was detected for daily commuting, which is less preferred with increasing distance and an employed partner. Furthermore, the intention to establish a second home is the highest when the distance is long and partner’s job opportunities are low. Finally, daily commuting is more preferred with lower than, with equal or higher job opportunities when the distance is 2.30 h.

Additional explorations have shown that the second home intention is strongest when neither migration nor commuting is clearly preferred. Hence, the relation between the difference in intentions to migrate and to commute and the intention for a second home are inverted U-shaped in this experiment. This also indicates that a second home becomes most attractive when people are irresolute with regard to migration and daily commuting.

Overall, the results provide first evidence concerning the role of a secondary home alternative in decision-making on residential mobility. It became especially obvious that a second home is attractive when it helps to compensate for extreme or irreversible costs of migration and commuting. Compared to migration, it reduces migration costs, and compared to commuting, it reduces transition costs. If either the transition costs or the migration costs are low, the second home alternative is not as attractive.

Our results are generally consistent with the results of previous factorial survey studies on moving intentions. Once again, home ownership and worse housing prospects turned out to be important obstacles of permanent migration while the partner’s job prospects are significant facilitators (Abraham and Schönholzer 2009, 2012; Abraham and Nisic 2012; Bähr and Abraham 2016). Similar to other studies, increasing distance gained a positive effect on the intention to migrate and a negative effect on the intention to commute (Abraham and Schönholzer 2009, 2012, Abraham and Nisic 2012). Nonetheless, our study goes a step further, as how the decisions on three types of regional mobility—migration, commuting, and a second home—are made and how various conditions and its interactions are related to them has not been explored until now.

Though factorial survey experiments serve for a high internal validity and unbiased effect estimation (Mutz 2011), results are limited in their external validity. We used a rather homogeneous sample of only academics from a single Swiss university. Hence, it is not clear to what extent the results can be generalised to other samples or populations. We want strongly to encourage replications of the experiment with more heterogeneous samples with regard to labour market segment, region, and country.

We varied primarily external conditions in the vignettes, though mobility intentions may depend on many more factors. These include, among others, additional transactional costs, childcare policies in a region, or consequences of relocating for children, especially from one school to another. It might be interesting in the future to include further conditions of the location, such as childcare facilities. Moreover, it would also be appealing to study the role of the respondents’ characteristics more intensively, e.g. effects of gender or attitudes towards residential mobility.

Furthermore, we did not differentiate between buying and renting at the destination but considered only real home ownership at the place of origin and housing prospects at the destination. It is very likely that, especially with regard to different types of mobility, renting or buying a residence would lead to different results. That is to say, all assets of location-specific capital that bind people to a place (cf. Mulder and Wagner 2012) would be worth being included as treatments in further experiments.

For Switzerland, it is reported that housing near motorways and a neighbourhood close to major urban centres are important facilitators of commuting across municipalities, both between urban and rural regions and between rural areas (Guth et al. 2011). Those regional and infrastructural conditions should, therefore, be examined in more detail in future applications. Relatedly, the role of smart internet working for residential mobility behaviour (cf. Ciari et al. 2013) could be explored.

One might also criticise that we treated internal and international moves equally as the jobs were either located in Switzerland or abroad. We included both conditions in the vignettes because spatial mobility requirements in the academic system are ubiquitous (cf. Bauder 2015) and in Switzerland, the labour market for academics is comparatively small. International mobility to, for instance, Germany or France can serve for better positions and career prospects (cf. Morano-Foadi 2005). Hence, at least for our specific sample, hypothetical job offers from both Switzerland and abroad are highly realistic and plausible. In addition, numerous authors emphasised various interconnections between internal and international migration (e.g. Lozano-Ascencio et al. 1999; King and Skeldon 2010) and most determinants have become important for both types of mobility in empirical studies, i.e. labour market prospects, wages, costs of living, and stocks of mobile people (Fourage and Ester 2007; Otoiu 2014). Our data allow for a closer look at the significance of national border crossings in decision-making on the three types of mobility in the future.

Finally, we measured only intentions to realise types of regional mobility given a certain job offer instead of the mobility behaviour. Though some studies report that migration intentions are valid predictors of subsequent migration behaviour (De Jong 2000; de Groot et al. 2011b; van Dalen and Henkens 2013), it has been extensively discussed in migration research that intentions or desires to move are not necessarily transferred into moving behaviour (e.g. Lu 1999; Kley 2011; Coulter et al. 2011; Groot et al. 2011a; Coulter and Scott 2015). Existing validation studies suggest that factorial survey experiments allow for valid conclusions about real-world behaviour. Particularly, the directions and relative sizes of estimated effects are reported to be consistent across hypothetical and real-world decision-making, for instance when voting about the naturalisation of immigrants (Hainmueller et al. 2015), when redirecting a misdirected e-mail (Petzold and Wolbring 2019), and even when making residential moves (Nisic and Auspurg 2009). Accordingly, our results need urgently to be compared with actual moving behaviour. This would also account for the fact that mobility decisions are discrete choices in reality (cf. van Ommeren et al. 2000).

Despite these limitations, factorial survey experiments are a promising approach to be applied in research on regional mobility and migration as they allow for a detailed and nuanced investigation of complex decision-making processes which is particularly reflected by the increasing variability in types of mobility.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, Switzerland [grant number 147932]. Parts of the study were presented at the International Symposium: Internal Migration and Commuting in International Perspective, February 2015, in Wiesbaden, Germany.

Appendix

See Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13.

Table 5.

Vignette judgments per respondent (vignettes/deck = 10)

| Judgments | N | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 3 | 5 | 0.86 |

| 4 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 5 | 3 | 0.52 |

| 6 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 7 | 5 | 0.86 |

| 8 | 15 | 2.58 |

| 9 | 60 | 10.31 |

| 10 | 491 | 84.36 |

| Total | 582 | 100 |

Table 6.

Frequencies of observations per vignette

| Vignette | N | Percent (%) | Cum. percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 44 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| 2 | 45 | 0.80 | 1.58 |

| 3 | 27 | 0.48 | 2.05 |

| 4 | 37 | 0.66 | 2.71 |

| 5 | 33 | 0.58 | 3.29 |

| 6 | 37 | 0.66 | 3.95 |

| 7 | 36 | 0.64 | 4.59 |

| 8 | 49 | 0.87 | 5.45 |

| 9 | 41 | 0.73 | 6.18 |

| 10 | 44 | 0.78 | 6.96 |

| 11 | 34 | 0.60 | 7.56 |

| 12 | 49 | 0.87 | 8.43 |

| 13 | 39 | 0.69 | 9.12 |

| 14 | 41 | 0.73 | 9.85 |

| 15 | 34 | 0.60 | 10.45 |

| 16 | 34 | 0.60 | 11.05 |

| 17 | 36 | 0.64 | 11.69 |

| 18 | 27 | 0.48 | 12.17 |

| 19 | 35 | 0.62 | 12.79 |

| 20 | 39 | 0.69 | 13.48 |

| 21 | 34 | 0.60 | 14.08 |

| 22 | 43 | 0.76 | 14.84 |

| 23 | 35 | 0.62 | 15.46 |

| 24 | 43 | 0.76 | 16.22 |

| 25 | 32 | 0.57 | 16.79 |

| 26 | 43 | 0.76 | 17.55 |

| 27 | 41 | 0.73 | 18.28 |

| 28 | 34 | 0.60 | 18.88 |

| 29 | 35 | 0.62 | 19.50 |

| 30 | 37 | 0.66 | 20.15 |

| 31 | 34 | 0.60 | 20.75 |

| 32 | 41 | 0.73 | 21.48 |

| 33 | 47 | 0.83 | 22.31 |

| 34 | 34 | 0.60 | 22.91 |

| 35 | 34 | 0.60 | 23.52 |

| 36 | 27 | 0.48 | 24.00 |

| 37 | 34 | 0.60 | 24.60 |

| 38 | 37 | 0.66 | 25.25 |

| 39 | 41 | 0.73 | 25.98 |

| 40 | 34 | 0.60 | 26.58 |

| 41 | 39 | 0.69 | 27.27 |

| 42 | 40 | 0.71 | 27.98 |

| 43 | 44 | 0.78 | 28.76 |

| 44 | 27 | 0.48 | 29.24 |

| 45 | 37 | 0.66 | 29.89 |

| 46 | 37 | 0.66 | 30.55 |

| 47 | 34 | 0.60 | 31.15 |

| 48 | 36 | 0.64 | 31.79 |

| 49 | 38 | 0.67 | 32.46 |

| 50 | 35 | 0.62 | 33.08 |

| 51 | 44 | 0.78 | 33.86 |

| 52 | 38 | 0.67 | 34.53 |

| 53 | 39 | 0.69 | 35.22 |

| 54 | 38 | 0.67 | 35.90 |

| 55 | 40 | 0.71 | 36.60 |

| 56 | 33 | 0.58 | 37.19 |

| 57 | 34 | 0.60 | 37.79 |

| 58 | 34 | 0.60 | 38.39 |

| 59 | 39 | 0.69 | 39.08 |

| 60 | 40 | 0.71 | 39.79 |

| 61 | 38 | 0.67 | 40.46 |

| 62 | 34 | 0.60 | 41.07 |

| 63 | 37 | 0.66 | 41.72 |

| 64 | 43 | 0.76 | 42.48 |

| 65 | 42 | 0.74 | 43.23 |

| 66 | 33 | 0.58 | 43.81 |

| 67 | 38 | 0.67 | 44.48 |

| 68 | 36 | 0.64 | 45.12 |

| 69 | 33 | 0.58 | 45.71 |

| 70 | 26 | 0.46 | 46.17 |

| 71 | 41 | 0.73 | 46.89 |

| 72 | 45 | 0.80 | 47.69 |

| 73 | 48 | 0.85 | 48.54 |

| 74 | 37 | 0.66 | 49.19 |

| 75 | 37 | 0.66 | 49.85 |

| 76 | 44 | 0.78 | 50.63 |

| 77 | 44 | 0.78 | 51.41 |

| 78 | 38 | 0.67 | 52.08 |

| 79 | 35 | 0.62 | 52.70 |

| 80 | 44 | 0.78 | 53.48 |

| 81 | 36 | 0.64 | 54.12 |

| 82 | 44 | 0.78 | 54.90 |

| 83 | 44 | 0.78 | 55.68 |

| 84 | 35 | 0.62 | 56.30 |

| 85 | 44 | 0.78 | 57.07 |

| 86 | 41 | 0.73 | 57.80 |

| 87 | 38 | 0.67 | 58.47 |

| 88 | 35 | 0.62 | 59.09 |

| 89 | 33 | 0.58 | 59.68 |

| 90 | 43 | 0.76 | 60.44 |

| 91 | 33 | 0.58 | 61.02 |

| 92 | 37 | 0.66 | 61.68 |

| 93 | 26 | 0.46 | 62.14 |

| 94 | 34 | 0.60 | 62.74 |

| 95 | 27 | 0.48 | 63.22 |

| 96 | 37 | 0.66 | 63.87 |

| 97 | 35 | 0.62 | 64.49 |

| 98 | 37 | 0.66 | 65.15 |

| 99 | 36 | 0.64 | 65.79 |

| 100 | 48 | 0.85 | 66.64 |

| 101 | 37 | 0.66 | 67.29 |

| 102 | 37 | 0.66 | 67.95 |

| 103 | 39 | 0.69 | 68.64 |

| 104 | 35 | 0.62 | 69.26 |

| 105 | 26 | 0.46 | 69.72 |

| 106 | 40 | 0.71 | 70.43 |

| 107 | 36 | 0.64 | 71.06 |

| 108 | 32 | 0.57 | 71.63 |

| 109 | 45 | 0.80 | 72.43 |

| 110 | 48 | 0.85 | 73.28 |

| 111 | 41 | 0.73 | 74.00 |

| 112 | 43 | 0.76 | 74.77 |

| 113 | 27 | 0.48 | 75.24 |

| 114 | 37 | 0.66 | 75.90 |

| 115 | 45 | 0.80 | 76.70 |

| 116 | 36 | 0.64 | 77.33 |

| 117 | 39 | 0.69 | 78.02 |

| 118 | 36 | 0.64 | 78.66 |

| 119 | 34 | 0.60 | 79.26 |

| 120 | 34 | 0.60 | 79.87 |

| 121 | 47 | 0.83 | 80.70 |

| 122 | 33 | 0.58 | 81.28 |

| 123 | 37 | 0.66 | 81.94 |

| 124 | 35 | 0.62 | 82.56 |

| 125 | 33 | 0.58 | 83.14 |

| 126 | 48 | 0.85 | 83.99 |

| 127 | 37 | 0.66 | 84.65 |

| 128 | 34 | 0.60 | 85.25 |

| 129 | 37 | 0.66 | 85.90 |

| 130 | 38 | 0.67 | 86.58 |

| 131 | 49 | 0.87 | 87.44 |

| 132 | 37 | 0.66 | 88.10 |

| 133 | 37 | 0.66 | 88.76 |

| 134 | 36 | 0.64 | 89.39 |

| 135 | 41 | 0.73 | 90.12 |

| 136 | 40 | 0.71 | 90.83 |

| 137 | 48 | 0.85 | 91.68 |

| 138 | 45 | 0.80 | 92.47 |

| 139 | 34 | 0.60 | 93.08 |

| 140 | 37 | 0.66 | 93.73 |

| 141 | 36 | 0.64 | 94.37 |

| 142 | 40 | 0.71 | 95.08 |

| 143 | 34 | 0.60 | 95.68 |

| 144 | 27 | 0.48 | 96.16 |

| 145 | 37 | 0.66 | 96.81 |

| 146 | 35 | 0.62 | 97.43 |

| 147 | 33 | 0.58 | 98.02 |

| 148 | 41 | 0.73 | 98.74 |

| 149 | 35 | 0.62 | 99.36 |

| 150 | 36 | 0.64 | 100.00 |

| Total | 5647 | 100.00 |

Table 7.

Frequencies of observations per deck

| Vignette deck | N | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 267 | 4.73 |

| 2 | 340 | 6.02 |

| 3 | 412 | 7.30 |

| 4 | 333 | 5.90 |

| 5 | 366 | 6.48 |

| 6 | 360 | 6.38 |

| 7 | 368 | 6.52 |

| 8 | 402 | 7.12 |

| 9 | 383 | 6.78 |

| 10 | 359 | 6.36 |

| 11 | 359 | 6.36 |

| 12 | 481 | 8.52 |

| 13 | 441 | 7.81 |

| 14 | 338 | 5.99 |

| 15 | 438 | 7.76 |

| Total | 5647 | 100 |

Table 8.

Regression models with Heckman correction on mobility intentions

| Willingness (selection) | Migration | Second home | Daily commuting | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Indicators | ||||||||

| Temporary (current) (ref. tenured) | − 0.063 | (0.172) | − 0.150 | (0.206) | 0.161 | (0.185) | 0.172 | (0.209) |

| Tenured (offer) (ref. temporary) | − 0.056 | (0.046) | 0.330*** | (0.053) | − 0.006 | (0.049) | 0.012 | (0.049) |

| Equal income (ref. lower) | 0.008 | (0.054) | 0.259*** | (0.070) | 0.098 | (0.064) | − 0.023 | (0.069) |

| Higher income (ref. lower) | 0.074 | (0.063) | 0.342*** | (0.070) | 0.088 | (0.076) | 0.062 | (0.072) |

| Equal position (ref. lower) | 0.105 | (0.057) | 0.103 | (0.063) | 0.131 | (0.069) | − 0.004 | (0.065) |

| Higher position (ref, lower) | 0.049 | (0.057) | 0.239*** | (0.065) | 0.151* | (0.071) | − 0.001 | (0.068) |

| Job content equal (ref. less) | − 0.001 | (0.054) | 0.434*** | (0.062) | 0.007 | (0.062) | 0.143* | (0.063) |

| Content more interesting (ref. less) | − 0.072 | (0.061) | 0.495*** | (0.065) | 0.007 | (0.066) | 0.181* | (0.071) |

| Suitable housing average (ref. worse) | 0.077 | (0.053) | 0.246*** | (0.061) | − 0.055 | (0.060) | − 0.078 | (0.065) |

| Suitable housing high (ref. worse) | 0.059 | (0.047) | 0.453*** | (0.059) | − 0.013 | (0.058) | − 0.174** | (0.063) |

| Flexible presence (ref. fix) | 0.086* | (0.042) | 0.004 | (0.048) | − 0.051 | (0.047) | − 0.089 | (0.049) |

| Distance 1 h 30 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | 0.107* | (0.053) | − 0.426*** | (0.072) | − 0.024 | (0.074) | 1.121*** | (0.080) |

| Distance 45 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | 0.214*** | (0.053) | − 1.097*** | (0.073) | − 0.827*** | (0.076) | 2.955*** | (0.088) |

| German-speaking Europe (not germ.-speak.) | 0.065 | (0.053) | − 0.041 | (0.060) | − 0.095 | (0.056) | 0.096 | (0.064) |

| Switzerland (not germ.-speak.) | 0.123* | (0.054) | − 0.059 | (0.061) | − 0.211** | (0.065) | 0.228*** | (0.065) |

| Spouse no job (current) (ref. yes) | − 0.195 | (0.164) | 0.601** | (0.198) | − 0.288 | (0.194) | 0.174 | (0.192) |

| Spouse job chance Equal (ref. lower) | 0.024 | (0.059) | 0.749*** | (0.067) | − 0.224** | (0.070) | − 0.170* | (0.071) |

| Spouse job chance higher (ref. lower) | 0.090 | (0.058) | 0.952*** | (0.075) | − 0.218** | (0.066) | − 0.260*** | (0.066) |

| No property owner (current) (ref. yes) | 0.086 | (0.143) | 0.637** | (0.207) | − 0.149 | (0.191) | − 0.467** | (0.181) |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age | 0.000 | (0.008) | − 0.013 | (0.012) | 0.023* | (0.011) | − 0.000 | (0.010) |

| Male (ref. female) | 0.034 | (0.095) | 0.195* | (0.099) | 0.146 | (0.122) | − 0.044 | (0.100) |

| Income | − 0.029 | (0.026) | − 0.019 | (0.033) | 0.031 | (0.034) | − 0.002 | (0.034) |

| Children (ref. no) | 0.150 | (0.096) | − 0.204 | (0.107) | 0.029 | (0.116) | − 0.020 | (0.104) |

| Associate professor (ref. full Prof.) | − 0.072 | (0.268) | 0.249 | (0.399) | − 0.037 | (0.314) | 0.190 | (0.314) |

| Assistant professor (ref. full Prof.) | 0.114 | (0.240) | 0.006 | (0.296) | 0.185 | (0.268) | − 0.212 | (0.253) |

| Postdoctoral researcher (ref. full Prof.) | 0.045 | (0.227) | − 0.008 | (0.294) | 0.092 | (0.297) | 0.481 | (0.288) |

| PhD student (ref. full Prof.) | 0.206 | (0.241) | − 0.161 | (0.308) | 0.427 | (0.314) | − 0.033 | (0.304) |

| Research assistant (ref. full Prof.) | − 0.273 | (0.172) | − 0.404 | (0.252) | 0.124 | (0.228) | 0.134 | (0.232) |

| Economics (ref. architecture) | 0.365 | (0.294) | − 0.230 | (0.295) | 0.191 | (0.413) | − 0.267 | (0.324) |

| Natural sciences (ref. architecture) | 0.216 | (0.217) | 0.532* | (0.240) | − 0.257 | (0.322) | − 0.095 | (0.245) |

| Engineerings (ref. architecture) | 0.222 | (0.228) | 0.384 | (0.251) | − 0.317 | (0.340) | − 0.154 | (0.256) |

| Social sciences (ref. architecture) | − 0.146 | (0.252) | − 0.107 | (0.306) | 0.025 | (0.370) | − 0.095 | (0.308) |

| Cultural sciences (ref. architecture) | 0.262 | (0.384) | − 0.054 | (0.383) | 0.499 | (0.518) | 0.473 | (0.394) |

| Educational sciences (ref. architecture) | 0.154 | (0.389) | 0.729 | (0.489) | 0.160 | (0.474) | − 0.172 | (0.391) |

| Human sciences (ref. architecture) | − 0.449 | (0.364) | − 0.115 | (0.336) | − 0.335 | (0.786) | 0.157 | (0.533) |

| Music and arts (ref. architecture) | − 0.139 | (0.410) | 0.663 | (0.384) | 1.032 | (0.670) | 0.394 | (0.612) |

| Management (ref. architecture) | − 0.517 | (0.337) | 0.241 | (0.568) | − 0.617 | (0.793) | 1.182*** | (0.340) |

| History and religion (ref. architecture) | − 0.672* | (0.299) | 0.110 | (0.501) | − 0.173 | (0.363) | − 0.546 | (0.728) |

| Other (ref. architecture) | 0.302 | (0.311) | 0.529 | (0.320) | 0.223 | (0.395) | 0.009 | (0.319) |

| Willingness | 2.756*** | (0.120) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nvignettes | 5647 | 5647 | 5647 | 5647 | ||||

| Ncensored | 1888 | 1888 | 1911 | 1902 | ||||

| Nuncensored | 3759 | 3759 | 3736 | 3745 | ||||

| Nrespondents | 582 | 582 | 582 | 582 | ||||

| Rho | − 0.683 | − 0.593 | − 0.489 | − 0.323 | ||||

| Sigma | 0.461 | 1.587 | 1.633 | 1.603 | ||||

| Lambda | – | − 0.942 | − 0.799 | − 0.519 | ||||

| Wald Chi2 | – | 812*** | 328*** | 1495*** | ||||

Heckman-corrected regressions; clustered standard errors in parentheses

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 9.

Craggit regression models on mobility intentions

| Willingness (tier 1) | Migration (tier 2) | Second home (tier 2) | Commuting (tier 2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Indicators | ||||||||

| Temporary (current) (ref. tenured) | 0.250 | (0.147) | 0.005 | (0.250) | 0.391 | (0.272) | 0.319 | (0.279) |

| Tenured (offer) (ref. temporary) | 0.283*** | (0.040) | 0.536*** | (0.061) | 0.162* | (0.072) | 0.109 | (0.067) |

| Equal income (ref. lower) | 0.336*** | (0.048) | 0.449*** | (0.079) | 0.349*** | (0.097) | 0.071 | (0.096) |

| Higher income (ref. lower) | 0.588*** | (0.054) | 0.650*** | (0.082) | 0.430*** | (0.110) | 0.258** | (0.097) |

| Equal Position (ref. lower) | 0.296*** | (0.048) | 0.261*** | (0.072) | 0.336** | (0.104) | 0.055 | (0.088) |

| Higher position (ref, lower) | 0.410*** | (0.049) | 0.445*** | (0.074) | 0.408*** | (0.106) | 0.116 | (0.092) |

| Job content equal (ref. less) | 0.375*** | (0.047) | 0.684*** | (0.071) | 0.240* | (0.093) | 0.323*** | (0.087) |

| Content more interesting (ref. less) | 0.564*** | (0.049) | 0.847*** | (0.075) | 0.352*** | (0.100) | 0.435*** | (0.095) |

| Suitable housing average (ref. worse) | 0.147*** | (0.043) | 0.315*** | (0.069) | − 0.038 | (0.089) | − 0.074 | (0.086) |

| Suitable housing high (ref. worse) | 0.230*** | (0.041) | 0.620*** | (0.066) | 0.091 | (0.086) | − 0.156 | (0.084) |

| Flexible presence (ref. fix) | 0.121*** | (0.036) | 0.052 | (0.054) | − 0.010 | (0.069) | − 0.083 | (0.065) |

| Distance 1 h 30 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | 0.123** | (0.044) | − 0.440*** | (0.079) | − 0.018 | (0.099) | 1.856*** | (0.129) |

| Distance 45 min (ref. 2 h 30 min) | 0.384*** | (0.046) | − 1.095*** | (0.083) | − 1.105*** | (0.116) | 4.019*** | (0.129) |

| German-speaking Europe (not germ.-speak.) | 0.030 | (0.044) | − 0.043 | (0.066) | − 0.131 | (0.081) | 0.122 | (0.086) |

| Switzerland (not germ.-speak.) | 0.169*** | (0.044) | − 0.034 | (0.070) | − 0.254** | (0.095) | 0.350*** | (0.089) |

| Spouse no job (current) (ref. yes) | − 0.102 | (0.131) | 0.633** | (0.198) | − 0.501 | (0.320) | 0.203 | (0.254) |

| Spouse job chance equal (ref. lower) | 0.268*** | (0.047) | 0.996*** | (0.078) | − 0.184 | (0.101) | − 0.103 | (0.097) |

| Spouse job chance higher (ref. lower) | 0.514*** | (0.049) | 1.318*** | (0.087) | − 0.085 | (0.096) | − 0.196* | (0.089) |

| No Property Owner (current) (ref. yes) | 0.153 | (0.128) | 0.838*** | (0.233) | − 0.164 | (0.279) | − 0.587* | (0.241) |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age | 0.003 | (0.008) | − 0.011 | (0.015) | 0.037* | (0.016) | 0.002 | (0.013) |

| Male (ref. female) | 0.031 | (0.080) | 0.236* | (0.110) | 0.232 | (0.182) | − 0.041 | (0.133) |

| Income | − 0.034 | (0.024) | − 0.038 | (0.039) | 0.023 | (0.051) | − 0.021 | (0.045) |

| Children (ref. no) | 0.050 | (0.083) | − 0.232 | (0.121) | 0.044 | (0.171) | − 0.041 | (0.141) |

| Associate professor (ref. full Prof.) | 0.069 | (0.248) | 0.412 | (0.472) | 0.075 | (0.474) | 0.351 | (0.412) |

| Assistant professor (ref. full Prof.) | 0.334 | (0.183) | 0.157 | (0.347) | 0.462 | (0.394) | − 0.169 | (0.345) |

| Postdoctoral researcher (ref. full Prof.) | 0.262 | (0.204) | 0.102 | (0.357) | 0.282 | (0.448) | 0.715 | (0.379) |

| PhD student (ref. full Prof.) | 0.325 | (0.213) | − 0.065 | (0.373) | 0.741 | (0.470) | 0.013 | (0.403) |

| Research assistant (ref. full Prof.) | − 0.176 | (0.160) | − 0.496 | (0.308) | 0.147 | (0.342) | 0.161 | (0.311) |

| Economics (ref. architecture) | 0.185 | (0.253) | − 0.301 | (0.349) | 0.280 | (0.559) | − 0.377 | (0.440) |

| Natural Sciences (ref. Architecture) | 0.101 | (0.180) | 0.573* | (0.281) | − 0.362 | (0.435) | − 0.145 | (0.323) |

| Engineerings (ref. architecture) | 0.093 | (0.194) | 0.408 | (0.293) | − 0.478 | (0.466) | − 0.235 | (0.339) |

| Social sciences (ref. architecture) | − 0.241 | (0.217) | − 0.245 | (0.364) | − 0.061 | (0.501) | − 0.210 | (0.417) |

| Cultural sciences (ref. architecture) | 0.540 | (0.354) | 0.082 | (0.480) | 0.894 | (0.714) | 0.671 | (0.506) |

| Educational sciences (ref. architecture) | − 0.078 | (0.337) | 0.667 | (0.589) | 0.097 | (0.682) | − 0.329 | (0.504) |

| Human sciences (ref. architecture) | − 0.564* | (0.275) | − 0.236 | (0.409) | − 0.642 | (1.367) | 0.112 | (0.657) |

| Music and arts (ref. architecture) | 0.008 | (0.458) | 0.812 | (0.509) | 1.542 | (0.875) | 0.521 | (0.712) |

| Management (ref. architecture) | − 0.029 | (0.280) | 0.330 | (0.713) | − 0.819 | (1.293) | 1.365*** | (0.412) |

| History and religion (ref. architecture) | − 0.275 | (0.252) | 0.197 | (0.647) | − 0.233 | (0.521) | − 0.716 | (1.020) |

| Other (ref. architecture) | 0.118 | (0.252) | 0.525 | (0.375) | 0.284 | (0.543) | − 0.058 | (0.420) |

| Nvignettes | 5647 | 5647 | 5647 | 5647 | ||||

| Nrespondents | 582 | 582 | 582 | 582 | ||||

| Log-likelihood | − 9962.72 | − 9962.72 | − 9850.55 | − 9793.28 | ||||

| Wald Chi2 | 658.27*** | 658.27*** | 639.83*** | 653.08*** | ||||

Craggit regressions; AME; clustered standard errors in parentheses

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Footnotes

Changes of benefits and costs over time are not considered here (e.g., Yapa et al. 1971; Schmidt 2014).

In addition, the attractiveness of a job can also be influenced by the conditions of regional mobility and, conversely, regional mobility can be pursued even if a job is less attractive. The issue of dependencies will be captured by statistical analyses.

The data generated and analysed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 × 3 = 8748.

Respondents who declared to be singles were presented vignettes without the partner dimension. This part of the study is not considered here. For detailed information and initial results, see Petzold and Hilti (2015).