Abstract

This study examines how individuals perceive children, focusing on two dimensions—the positive aspects of having children and the perception of children as a burden—and taking into account relations with both individual- and macro-level characteristics. Three dimensions are examined on the macro-level: policies that support families, the cultural environment, and economic conditions. The study is based on the 2012 ISSP module on “Family and Gender Roles” and covers 24 OECD countries. The findings show that countries vary widely in their negative perceptions of children, but evince relatively greater similarity in their positive perceptions. Institutional support for children and working parents and traditional family values as captured by religiosity are important factors in explaining cross-country variation in negative perceptions of children. Further, policies may help men and women adopt a more positive view of children and reduce differences among educational groups in relation to children.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10680-019-09535-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Children, Attitudes, ISSP, Comparative study

Introduction

The decline in fertility in most Western countries has attracted much attention from researchers and policymakers. The past research attributed this decline to a variety of economic, social, and cultural determinants (Adsera 2011; Mace 2013). Besides this general trend, there is also considerable variation in fertility levels and fertility trends across countries, and even a reversal of the decline in some (Esping-Andersen and Billari 2015). The decision to have children is affected by a complex set of factors, some economic in nature, others related to cultural norms and to the psychological or social consequences of having (or not having) children (Fawcett 1978, 1988; Hoffman and Hoffman 1973; Liefbroer 2005; Mace 2013). Economic theory (e.g. Becker 1981) emphasizes the costs and benefits associated with having children, which determine the number of children as well as the timing of their births. Other perspectives emphasize cultural values that affect attitudes towards children and fertility level (Ekert-Jaffe and Stier 2009; Inglehart 1997; 2015; Inglehart and Baker 2000; Mace 2013).

Our study aims to explore the way individuals perceive children. Prior studies have focused mainly on children as contributing to families’ wellbeing (e.g. Aassve et al. 2016; Nelson et al. 2014; Jones and Brayfield 1997; Tanaka and Lowry 2011). Our study contributes to this line of inquiry primarily in two ways. First, we see the perceptions of children as a multidimensional construct, distinguishing positive from negative attitudes towards them. Under “positive”, we include views that see the benefit of having children in terms of social standing, social support, or psychological wellbeing (Nauck and Klaus 2007). Under “negative”, we introduce the perception of children as a burden, taking into account their costs and disturbance to parents’ freedom and careers (Henz 2008). Second, we contribute to the existing literature by looking at cross-country variation in attitudes towards children, more particularly by asking whether social policy can explain this variation: Can social policies reduce the perception of children as a burden? Do they increase the perception of children as a benefit? Although the relations among childbearing behaviour, cultural norms, and family policies are complex and interdependent (Pfau-Effinger 2004), the way individuals perceive children—and the factors associated with these perceptions at both the micro- and macro-levels—could shed light on fertility intentions, as well as on constraining and facilitating mechanisms in respect of having children, as attitudes towards children are associated with fertility level (Barber 2001). These perceptions may also bring to light the importance of social policy in explaining positive and negative attitudes towards children. All in all, we have three research questions. First, how do positive and negative attitudes to children vary across countries? Second, how do individual-level characteristics relate to these attitudes? And third, what are the macro-level dimensions associated with positive and negative attitudes towards children?

Perceptions of Children

The role of children changed considerably in the second half of the twentieth century (Zelizer 1985). While all societies value childbearing, variation in individuals’ perception of the importance of children increased with changes in the role of children, cultural values, economic conditions, and gender roles. Accordingly, some may see the social, economic, or psychological benefits of having children, while others may view them as costly or hampering life plans. Structural changes associated with the industrialization process (Inglehart 1997) have also changed the way individuals perceive the benefits and costs of children. As Inglehart and Baker (2000) claim, economic development, affluence, and the rise of the welfare state in certain countries have also affected the cultural values of many aspects of life, especially the role and centrality of family. Normative changes are most pronounced in affluent societies, where the traditional values of childbearing and family life have changed considerably. From a somewhat different angle, the “second demographic transition” (SDT) (Lesthaeghe 1995, 2010) emphasizes increased individualization, autonomy, and self-realization in most industrialized countries, which has affected family behaviour, including childbirth. These structural and individual changes have likewise affected both the contribution of children to their families and the cost of children.

Regarding the contribution of children, it has been argued that in more traditional societies family and childbearing constitute a central aspect of life. Inglehart and Baker (2000) suggest that in such societies children contribute much to their parents (socially and often economically), while in more modern societies parents think of their children’s wellbeing as more important than their own, thereby increasing the children’s costs. Men and women value children out of psychological rather than economic considerations (Zelizer 1985). Children might be perceived as contributing to parents’ happiness and also as a significant aspect of their social role and identity (Aassve et al. 2016; Nelson et al. 2014; Hoffman et al. 1978). They still have an important role in supporting aged parents, socially and in some contexts also economically (Henz 2008).

But children are also a source of stress for parents, as Nelson et al. (2014) indicate. With economic development and transformations in education, work, and welfare, the rational calculation of costs and benefits has shifted from the quantity to the quality of children (Lawson and Mace 2010, 2011). Investments in children have intensified over time (Bianchi 2000; Craig et al. 2014) for all strands of society (Lawson and Mace 2010) in order to prepare them for contemporary economies. Nowadays children are more costly, especially in contexts where they depend on their parents for a substantial length of time owing to prolonged education and later age of transition to adulthood (Furstenberg et al. 2004). These costs might affect the way individuals perceive children and the number of children they aspire to have. Moreover, children can be viewed as interfering with their parents’ career aspirations, especially women’s, and with their chosen lifestyle (Henz 2008). The rise in women’s employment and the emergence of the dual-earner family as a modal family in many countries have increased the incompatibility between paid work and care work, which in turn has elevated the cost of children. Accordingly, children have come to be considered the main obstacle to mothers’ career development, affecting women’s labour market position and their pattern of work (Gash 2008; Gornick and Meyers 2003; Moen and Han 2001; Stier et al. 2001; Van der Lippe and van Dijk 2002). With the difficulty of balancing work and family and the growing importance of human capital accumulation increasingly affecting both parents, the desire to have (more) children has been further diminished (Aggarwal et al. 2013). Both aspects of attitudes towards children—positive and negative—can be related to individual- as well as institutional-level characteristics, as we discuss below.

Attitudes Towards Children at the Micro-level

Theoretically, several characteristics are related to attitudes towards children. First, men and women might perceive children differently (Henz, 2008). The costs of children are considered heavier for women than for men, mainly because in all countries women bear the major responsibility for childcare (Gash 2009; Cooke 2014; Stier et al. 2001). The presence of children affects women’s work patterns throughout their life course (Gash 2008; Moen and Han 2001; Stier et al. 2001; Uunk et al. 2005), the type of occupations they hold (Abendroth et al. 2014), and their achievements in the labour market (Budig and England 2001; England 2005; Budig et al. 2012; Misra et al. 2011). Childbearing is considered one of the main determinants of the gender pay gap in many countries (Budig and Hodges 2010; England 2005, 2010; Cooke 2014; Gash 2009). These costs are especially high for women who aspire to a demanding career, which escalates the conflict between work and family (England et al. 2016; Cha and Weeden 2014). In other words, women have more to lose by having children, especially when they have rewarding opportunities in the labour market. As Liefbroer (2005) found, men expect lower costs of having a child and greater rewards than women. Women also express less traditional views than men about family, marriage, and children (Gubernskaya 2010; Merz and Liefbroer 2012).

At the same time, in some countries, even in contemporary societies, motherhood is perceived as a defining characteristic of womanhood (Hakim 2002; Henz 2008). Hence, women more than men might perceive children as contributing to their happiness and to their social role and identity (Cinamon and Rich 2002; Gaunt and Scott 2017).

Second, values and ideologies in contemporary industrialized countries also affect the way people perceive children, in both dimensions. Inglehart and Baker (2000) argue that in traditional societies children contribute to parents by making them proud and respecting them, while in industrialized societies parents must invest as much as possible in their children, even at the expense of their own wellbeing. Yet they also argue that cultural perceptions, especially those influenced by religion and ideologies, often continue to affect attitudes even in the most advanced societies (Mace 2013). From a different perspective, proponents of the second demographic transition (Surkyn and Lesthaeghe 2004; Lesthaeghe 2010) argue that cultural changes, in particular the rise in individualistic values that emphasize self-realization and personal needs, account for the decline in fertility and the rise in childlessness (Lesthaeghe 2010). These emerging values are incompatible with traditional views of marriage and childbearing (Beck-Gernsheim 2002), as they emphasize educational achievements and career building as ways to self-realization rather than parenthood. This approach also claims that education and secularization are associated with changes in values and attitudes towards family life (Yucel 2015).

The effect of education on attitudes towards children is also related to the costs of children, as education determines families’ economic standing and women’s work patterns. While from an economic viewpoint (e.g. Becker 1981) more affluent individuals will probably prefer more children (hence will have a more positive attitude towards them), studies show that this is not always the case (Mace 2013; Lawson and Mace 2010). This is probably because the investment in children increases with affluence, raising the costs of each child. Also, for highly educated women the costs in lost opportunities are much higher than for women with lower education, which affects their perception of children as a burden.

While attitudes towards children carry important policy implications, as more positive attitudes could lead to earlier childbearing and higher fertility (Barber 2001), relatively few studies have analysed this issue—in general, and in a comparative setting in particular (see, for example, Gubernskaya 2010; Jones and Brayfield 1997; Tanaka and Lowry 2011; Yucel 2015). Studies on attitudes towards children have found interesting gender differences, although these findings are not conclusive. Some studies find that women are less likely than men to view children as central (Jones and Brayfield 1997; Kaufman and Goldscheider 2007). Others, however, found no differences (Henz 2008) or found that women had more positive attitudes towards children than men and saw them as central to their identity and parental role (Cinamon and Rich 2002; Gaunt and Scott 2017). Children were found to be less central for less religious individuals, and for those holding less traditional attitudes towards gender roles (Gubernskaya 2010; Jones and Brayfield 1997; Yucel 2015). Similarly, traditional values and religiosity were associated with attitudes towards voluntary childlessness (Liefbroer and Billari 2010; Merz and Liefbroer 2012; Miettinen et al. 2015). The findings regarding educational attainment are less consistent, with some pointing to higher support of childlessness among the better educated (e.g. Merz and Liefbroer 2012), while others find higher support among the less educated, although also among highly educated women (Miettinen et al. 2015).

Lastly, although studies show that employed individuals in general are less supportive of children (Trent and South 1992; Gubernskaya 2010), when they, particularly women, enjoy good arrangements for combining parenthood and employment, their attitudes towards children may be more positive (Adsera 2011; Ekert-Jaffe and Stier 2009).

The Institutional Context and Attitudes Towards Children

Individuals differ in their perception of children, depending on their social and economic conditions or their value orientation. But attitudes are also shaped by institutional and cultural conditions (Mace 2013). As argued above, children can be perceived as a burden because they entail economic and emotional costs. At the same time, they can be seen as contributing to their parents emotionally or socially, increasing parental happiness and social standing, or providing them social support. These elements might differ by country and depend on a variety of institutional arrangements: public policies aimed directly at reducing the costs of children; institutional arrangements that lower the opportunity costs associated with having children and the reliance of parents on their support later in life; cultural norms that affect the view of children; and economic conditions and opportunities in the labour market that influence the costs of children.

Regarding public policy, this includes policies that provide direct support for the family, through allowances or parental leave, as well as conditions that improve the balance between work and family such as subsidized day-care arrangements and long school days. These types of policy were found to affect women’s employment patterns (Gornick and Meyers 2003; Mandel and Semyonov 2005; Stier et al. 2001), work-family balance (Stier et al. 2012), parental wellbeing (Glass, Anderson and Simon 2016), and even fertility level (Kalwij 2010; Wesolowski and Ferrarini, 2018).

In addition to policies and institutional arrangements, culture too plays an important part in shaping attitudes. The way children are perceived, their benefits (as well as their costs) are viewed through specific different cultural lenses (Ekert-Jaffe and Stier 2009; Gubernskaya 2010; Jones and Brayfield 1997; Mace 2013). In pro-natalist contexts and in countries were traditional family values prevail; for example, children might be viewed more positively and their costs and burdens might be overlooked because society places a high value on childbirth and parenthood (Hashiloni-Dolev 2006). Lastly, economic conditions and opportunities in the labour market might also play a part in explaining positive and negative attitudes towards children (Nauck and Klaus, 2007). Rising unemployment causes delays and a decline in partnership formation, which often indirectly contributes to the decline in first-birth rates (Sobotka, Skirbekk and Philipov, 2011).

Relatively few studies have examined attitudes towards children across countries; mainly, they investigate general attitudes towards family and children, or they compare attitudes in a few countries, but they do not test directly the relation of policies and cultural indicators to how children are perceived (Gubernskaya 2010; Jones and Brayfield 1997; Yucel 2015; Miettinen et al. 2015). In general, these studies have found that women and more secular individuals hold less traditional views on marriage and children, although, as pointed out above, the findings are less consistent regarding education. Despite a general trend of less support for marriage and children across countries, cross-national and sociodemographic differences persist (Gubernskaya 2010; Yucel 2015; Miettinen et al. 2015). These findings point to the importance of public policy, which these studies did not examine directly (Gubernskaya 2010). The present study aims to fill this gap by examining two dimensions of attitudes towards children in a large number of OECD countries. It takes into account both individual- and macro-level characteristics. Following the discussion above, three dimensions are examined at the macro-level: policy, culture, and economic conditions.

Hypotheses

From the arguments above, we derive several hypotheses regarding both negative and positive attitudes towards children. Starting with individual-level characteristics, we focus mainly on gender, religiosity, and education. Because women are the main caregivers and encounter high wage penalties and career constraints (Budig et al. 2012), the costs of children are considered heavier for women than for men. As studies show that men view children as more beneficial to them than women do (Liefbroer 2005), and women have less traditional attitudes towards marriage and children (Gubernskaya 2010; Merz and Liefbroer 2012), we expect (H1): women will have more negative and less positive attitudes towards children than men.

Education and religiosity might also be related to attitudes towards children, as suggested by Inglehart and Baker (2000) as well as the SDT approach (Lesthaeghe 2010). Based on their arguments and previous findings (Lawson and Mace 2010; 2011; Liefbroer and Billari 2010), we expect (H2): the higher the educational level, the lower the positive perceptions of children and the higher the negative perceptions; and (H3): religious individuals presumably have more positive and less negative perceptions of children.

Three main characteristics are tested at the macro-level. First, regarding policy, we focus on two main aspects of policy that indicate direct support for families and improve the work-family balance: state support for children and state support for working parents. These aspects have been found to be important for women’s employment, parental wellbeing and fertility (e.g. Stier et al. 2012; Glass, Anderson and Simon 2016; Kalwij 2010, respectively). Accordingly, we hypothesize (H4): the higher the state support for children and working parents, the lower the negative attitudes and the higher the positive attitudes towards children.

Second, given cultural effects on attitudes (Ekert-Jaffe and Stier 2009; Gubernskaya 2010; Jones and Brayfield 1997) and the differences in traditional family values across cultures (Hashiloni-Dolev, 2006; Liefbroer and Rijken 2019), we expect (H5): the more supportive the cultural environment of children in a country, the more positive and less negative attitudes towards children will be.

Third, from an economic perspective it is assumed that economic hardship (at the state level) is related to attitudes towards children (Nauck and Klaus, 2007). Hence, we hypothesize (H6): the greater the economic hardship in the country, the more negative and less positive attitudes towards children will be.

Lastly, our theoretical model also assumes an interaction between individual- and macro-level characteristics. We hypothesize (H7): the effect of gender, religiosity, and education will be smaller in countries that provide support for working parents. This is because such support allows individuals with difficulties (e.g. working parents) or holding less traditional views on families to display more favourable and less negative attitudes towards children.

Data and Measurements

The study is based on the 2012 wave of the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) module on Family and Gender Roles (http://www.issp.org). The ISSP is a cross-national collaborative programme that conducts annual surveys on diverse topics. The Family and Gender Roles module conducted in 2012 includes attitude towards employment of mothers; role distribution of the man and the woman in occupation and household; attitudes towards marriage, cohabitation, and divorce; attitudes towards children; household division of labour, and more. The survey was conducted in 41 countries. The current analysis covers 24 OECD countries for which country information is available: Austria, Belgium, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, South Korea, the UK, and the USA. The total sample is about 30,000 women and men from 24 countries.

The aim of this study is to explain cross-individual as well as cross-country variation in the perception of children. To that end, we used a set of questions on attitudes towards children. Respondents were asked to state whether they agreed or disagreed with the following six statements: watching children grow up is the greatest joy in life; children interfere too much with parents’ freedom; children are a financial burden on their parents; children restrict the career chances of one or both parents; children elevate the family’s social standing; adult children are an important source of help for elderly parents. All items were recoded so as to range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The three “negative” statements are highly correlated (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.7, ranging from 0.54 to 0.74 across countries), and therefore, we combined them into one measure of negative attitudes by averaging the scores (again, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).1 The three “positive” measures were very weakly correlated (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.4, ranging from 0.18 to 0.6 across countries), and therefore, we analysed each item separately.

At the individual level, we included respondent’s gender (women = 1; men = 0); education, measured as a set of dummy variables indicating whether respondent has less than high school education, high school, or some (non-university) post-high school education, and university education (as the reference category). Religiosity was indicated by attendance at religious services (1 = never … 8 = several times a week) so that a high value indicates a high level of religiosity (the original variable was recoded). Because we also include the average level of religiosity at the country level (see below), this variable was centred around the country’s mean. All models controlled also for age, marital status (1 = married or living together like a married couple, 0 = otherwise [un-partnered]), and Work status (respondent works fulltime—the reference category, part time, is not in the labour force).

The main interest of this study is in the role of macro-level indicators in shaping attitudes towards children. At this level, to measure policy dimensions, we used two indicators: support for working parents was measured by the number of weeks of paid parental leave; state support for children was measured by the number of children aged 0–2 in day-care2 (all obtained from the OECD family database and pertaining to the year 2010 (or close to that year in some countries)). To denote the cultural environment, we used the country’s level of religiosity, obtained from the ISSP (2012) survey.3 Religiosity was found in the past research to be a good indicator of traditional family values (see Liefbroer and Rijken 2019). Finally, unemployment rate (obtained from the International Labour Organization 2010) indicated the country’s economic conditions. All macro-level variables were measured around 2010. “Appendix A1” (online) presents the values of all macro-level items and their sources. Other measures of policies and economic conditions were considered (e.g. the country’s GDP; public expenditure on childcare; % women in part-time employment—all obtained from OECD publications; gender-role attitudes—constructed from the 2012 ISSP data). However, because they were highly correlated with other indicators, which are central to our theoretical arguments (e.g. GDP with percentage of children aged 0–2 in day-care; female labour force participation with paid parental leave; gender-role attitudes with paid parental leave and religiosity), or did not significantly affect the results (e.g. GINI), we did not include them in the final models.4 Descriptive statistics for all research variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the research variables: micro- and macro-indicators

| Variables | Percentages/mean (SD) | % missing |

|---|---|---|

| Individual-level variables | ||

| Gender: % women (Ref: men) | 55% | 0.1 |

| Religiosity | 5.84 (2.19) | 3.1 |

| Education | 1.1 | |

| Less than high school | 35% | |

| High school + some post-high school | 37% | |

| University education | 28% | |

| Work status | 0.9 | |

| Full time | 46% | |

| Part time | 12% | |

| Not in labour force | 43% | |

| Marital status: % married or living together (ref: un-partnered) | 57% | |

| Age | 49.35 (17.5) | 0.7 |

| N | 30,022 | |

| Country-level variables | ||

| Unemployment rate | 8.50 (3.7) | |

| Weeks paid parental leave | 58.30 (48.32) | |

| % Children 0–2 in day-care | 31.88 (10.4) | |

| Level of religiosity | 3.23 (0.88) | |

| N | 24 | |

Analytical Strategy

The study focuses on attitudes towards children and how they vary across individuals and countries. We employed a hierarchical linear modelling technique (Bryk and Raudenbush 1992). This methodology combines macro- and micro-level research, as it attempts to explain relationships at the individual level embedded in specific institutional contexts. We can model simultaneously the factors associated with country differences in attitudes towards children, while controlling for individual-level characteristics. Moreover, it allows testing whether important characteristics such as gender, religiosity, and education differ across countries, and how this variation is associated with country-level characteristics. Thus, a two-level model allows the researcher to define any number of individual-level variables as random variables, which are then regressed on the societal-level variables.5

For all measures, regression analysis was used, within the framework of hierarchical linear modelling. Such a model can be represented by a set of equations, for example,

| 1 |

The first is a within-country equation where the attitudes of individual i in country j are the dependent variable; β0j denotes the (country-specific) intercept; β1j, β2j, and β3j represent the effects of education, religiosity, and gender, respectively, and the vector X denotes all other individual-level control variables, β represents their coefficients, and εij is the error term. In this equation, both the intercept and the education, religiosity, and gender coefficients (β0j, β1j, and β2j, respectively) are allowed to vary cross-nationally, while the effects of the control variables are constrained to be the same across countries. We explain between-country variation with the country-level characteristics, as presented in Eqs. (2), (3), and (4).

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

In Eqs. (2), (3), and (4), the β coefficients derived from Eq. (1) constitute the dependent variables. In Eq. (2), the variation in average attitude across countries (variation in the intercept) is modelled as a function of contextual factors. In Eqs. (3) and (4), country differences in the effect of the respondent’s education and religiosity on attitudes (country-specific coefficients β1j and β2j) are modelled as a function of the countries’ characteristics. Because models are nested hierarchically, the fit of models is determined by Chi-square tests. The Chi-square is based on the log likelihood and indicates the difference between two nested models’ deviance statistics. It is used to determine whether a significant difference between the two models exists when model parameters are added or eliminated (see Whittaker and Furlow 2009).

Findings

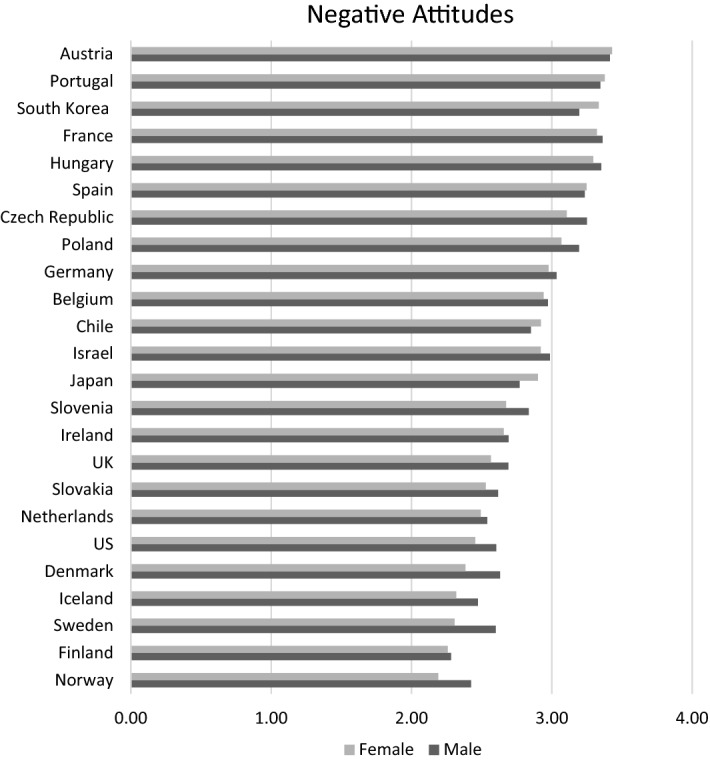

We begin by presenting the distribution of negative (Fig. 1) and positive (Fig. 2a–c) attitudes towards children by gender and country. Negative attitudes imply a perception of children as a burden, restricting parents’ employment opportunities, and interfering with their freedom. On a range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), we see a fairly varied perception among countries, from 2.2 for Norwegian women and 2.3 for Finnish men to about 3.4 for Austrian men and women. We also see that women (and to a lesser extent men) in all social–democratic Scandinavian countries have lower negative perceptions of children than do women in other countries; that is, children in these countries are less perceived as a burden on their parents. This is in line with the argument that with state support for families, as in these highly developed welfare states, children are less likely to be perceived as costly. By contrast, women and men from Portugal, Spain, Hungary, South Korea (only women), France, and Austria have a higher tendency to see children as an economic burden and a barrier to parents’ career and self-fulfilment. With regard to gender, in about half of the countries there are no significant differences between women and men; in most other countries, men tend to have more negative attitudes (with the exception of South Korea and Japan), contrary to our expectation (see H1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of negative attitudes towards children by gender and country, ISSP 2012 (the higher the value, the more negative the attitudes). Note T test reveals significant gender differences in: Czech Republic, Denmark, Iceland, Japan, South Korea, Norway, Poland, Slovenia, Sweden, the UK, and the USA

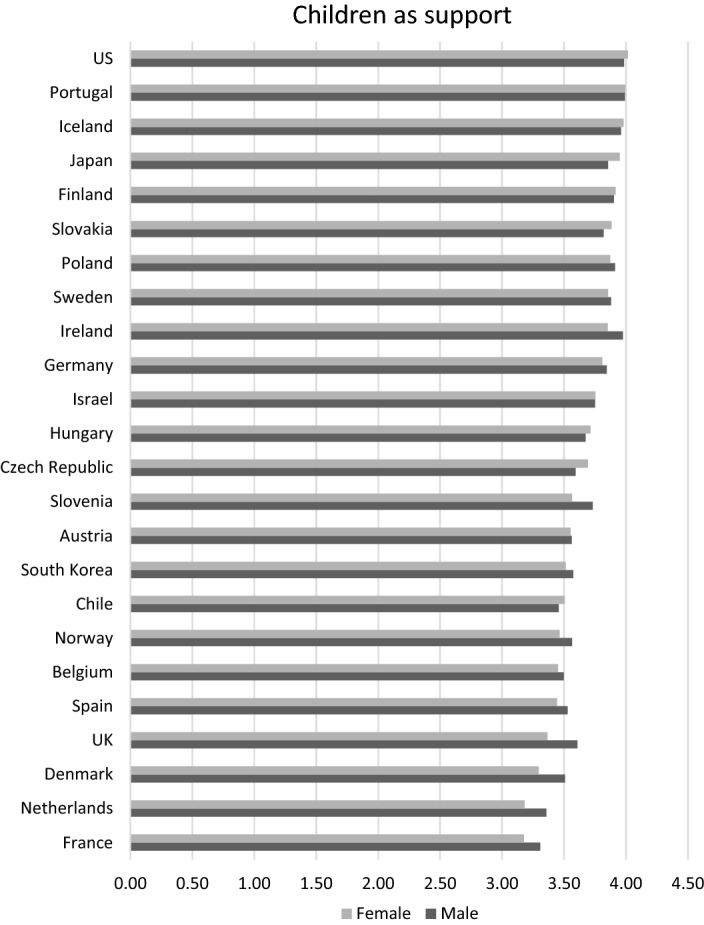

Fig. 2.

Distribution of positive attitudes towards children by gender and country, ISSP 2012 (the higher the value, the more positive the attitudes). a T test reveals significant gender differences in: Austria, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, the UK, and the USA. b T test reveals significant gender differences in: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Japan, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, Spain, the UK, and the USA. c T test reveals significant gender differences in: Czech Republic, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, and the UK

Positive attitudes represent the perception that children are a major source of happiness, contribute to the family’s social standing, and provide support for elderly parents (Fig. 2a–c). On all three measures, we found less variation among countries for both women and men, and this is especially pronounced in the first item: watching children grow is a source of joy for parents. For this item, the means range from about 4 for Dutch men and women to about 4.5 for men and somewhat higher for women in Slovenia. In half of the countries, women view children more positively than men do, contrary to our expectations (H1). The second item, i.e. children contribute to the family’s social standing, enjoys lower consensus: the means range from 2.8 and 2.5 in Spain for men and women, respectively, to 3.7 in Iceland for both men and women. Apparently, more variation exists across countries; also gender differences are somewhat more pronounced than in the preceding item. In most countries, men tend to agree more than women that children contribute to the family’s social standing, as we expected. Regarding the last item, i.e. children being seen as a source of support for old age, the means range from about 3.2 in France to 4 in the USA, with only slight gender differences across countries. In several countries, men tend to agree more than women that children serve as a source of support (e.g. Ireland, Slovenia, the UK, Denmark, the Netherlands, and France).

Individual- and Country-Level Correlates of Attitudes Towards Children

To understand the relations of both individual- and macro-level characteristics and how individuals perceive children in contemporary societies, we turn to multivariate analyses. As noted above, we estimated multilevel models in which individuals are embedded within countries. Before presenting the estimates of these models, we examine the variance components of the different attitude items. Table 2 presents the results. The most variation in all attitude items is evident between individuals, as expected. The variation across countries is statistically significant in all attitude measures; however, it is most pronounced in the negative attitudes. Here, 16.2% of the variance can be attributed to country differences in attitudes towards children. Cross-country variation is quite low for positive attitudes, ranging from 5% in the perception of children as a source of support to only 3.8% in the perception of children as a joy, with the contribution of children to social standing in between. The low variation means that macro-level variables explain little regarding positive attitudes.

Table 2.

% Cross-country variance of negative and different items of positive attitudes towards children

| Negative | Positive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joy | Social standing | Social support | ||

| Individual | 0.700 | 0.574 | 1.199 | 0.993 |

| Country | 0.135 | 0.023 | 0.056 | 0.054 |

| Total | 0.835 | 0.597 | 1.255 | 1.045 |

| % Country variation | 0.162 | 0.038 | 0.045 | 0.051 |

| N | 30,068 | |||

We estimate several models predicting negative and three positive perceptions, presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. In Table 3, focusing on negative attitudes, three models are tested: the first includes only individual-level indicators (model 1), the second adds country-level variables (model 2), and in the last (model 3) interactions between individual-level and country-level variables are added. All models allow a random intercept and a random effect for religiosity and education, as we expected (H7) that the effect would vary across countries with different levels of support for the family (the macro–micro-interaction). Gender was not included as a random variable because preliminary analysis showed that the policy indicator had no significant relationship with gender, and we preferred a more parsimonious model. The models’ Chi-square tests and log likelihood are presented at the bottom of the table.

Table 3.

Multilevel regression models predicting negative perceptions of children

| Individual (1) | +Macro (2) | +micro–macro-interactions (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual level | |||

| Women (ref: men) | − 0.060* (0.023) | − 0.060* (0.023) | − 0.060* (0.023) |

| Religiosity | − 0.023* (0.004) | − 0.023* (0.004) | − 0.023* (0.004) |

| Education (ref: university education) | |||

| Less than high school | − 0.010 (0.028) | − 0.012 (0.028) | − 0.010 (0.028) |

| High school + some post-high school | − 0.034 (0.018) | − 0.036* (0.018) | − 0.036* (0.017) |

| Work status (ref: full time) | |||

| Part time | − 0.009 (0.018) | − 0.009 (0.018) | − 0.009 (0.018) |

| Not in LF | 0.072* (0.013) | 0.072* (0.013) | 0.072* (0.013) |

| Married/coupled (ref = un-partnered) | − 0.097* (0.011) | − 0.097* (0.011) | − 0.097* (0.011) |

| Age | − 0.003* (0.000) | − 0.003 (0.001) | − 0.003* (0.001) |

| Intercept | 2.925 (0.063) | 2.928 (0.056) | 2.927 (0.052) |

| Effect on Intercept | |||

| Unemployment rate | 0.015 (0.011) | 0.013 (0.011) | |

| Weeks paid care leave | − 0.006* (0.001) | − 0.004* (0.001) | |

| % children 0–2 in day-care | − 0.015* (0.003) | − 0.016* (0.003) | |

| Religiosity level | − 0.139* (0.060) | − 0.141* (0.059) | |

| Effect on religiosity | |||

| Paid care leave | − 0.0002* (0.0001) | ||

| Effect on less than high school | |||

| Paid parental leave | − 0.0002 (0.0004) | ||

| Effect on high school | |||

| Paid parental leave | 0.0008* (0.0004) | ||

| N | 30,002 | 30,002 | 30,002 |

| X2 intercept (df) | 1817.9(23) | 1155.3(19) | 1122.4(19) |

| X2 religious (df) | 60.4(23) | 60.1(23) | 53.1 (22) |

| X2 less than HS (df) | 96.6(23) | 96.6(23) | 95.9 (22) |

| X2 HS (df) | 48.6(23) | 48.5(23) | 42.3 (22) |

| − 2 LL | 74181.6 | 74198.8 | 74233.8 |

| % Country variation | 17.3 | 12.7 | 12.0 |

*p < 0.05

Table 4.

Multilevel regression models predicting positive perceptions of children

| Joy | Social standing | Social support | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Individual level | ||||||

| Women (ref: men) | 0.100* (0.017) | 0.100* (0.016) | − 0.174* (0.023) | − 0.173* (0.022) | − 0.068* (0.020) | − 0.067* (0.019) |

| Religiosity | 0.026* (0.004) | 0.026* (0.004) | 0.044* (0.006) | 0.044* (0.006) | 0.043* (0.007) | 0.043* (0.007) |

| Education (ref: university education) | ||||||

| Less than high school | 0.164* (0.031) | 0.164* (0.029) | 0.115* (0.040) | 0.114* (0.038) | 0.116* (0.031) | 0.116* (0.031) |

| High school + some post-high school | 0.119* (0.017) | 0.118* (0.015) | 0.020 (0.026) | 0.018 (0.024) | 0.006 (0.018) | 0.006 (0.019) |

| Work status (ref: full time) | ||||||

| Part time | 0.034* (0.014) | 0.034* (0.014) | 0.043* (0.020) | 0.045* (0.019) | 0.045* (0.018) | 0.046* (0.018) |

| Not in labour force | 0.000 (0.015) | − 0.000 (0.015) | 0.075* (0.018) | 0.075* (0.018) | 0.094* (0.021) | 0.094* (0.021) |

| Married (ref: un-partnered) | 0.186* (0.016) | 0.186* (0.016) | − 0.011 (0.021) | − 0.011 (0.021) | − 0.063* (0.019) | − 0.063* (0.020) |

| Age | 0.002* (0.001) | 0.002* (0.001) | 0.003* (0.001) | 0.003* (0.001) | − 0.005* (0.001) | − 0.005* (0.001) |

| Intercept | 4.080 (0.037) | 4.081 (0.036) | 3.072 (0.056) | 3.073 (0.054) | 3.663 (0.046) | 3.664 (0.046) |

| Effect on intercept | ||||||

| Weeks paid parental leave | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 ~ (0.000) | 0.000 (0.001) | |||

| Effect on gender | ||||||

| Paid parental leave | 0. (0.000) | 0.001* (0.000) | 0. (0.002) | |||

| Effect on less than high school | ||||||

| Paid parental leave | − 0.001* (0.000) | − 0.002* (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |||

| Effect on high school | ||||||

| Paid parental leave | − 0.008* (0.003) | − 0.001* (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |||

| N | 30536 | 30,536 | 29,713 | 29,713 | 30,580 | 30,580 |

| X2 Intercept (df) | 345.1 | 364.1(23) | 336.7(22) | 325.25*(23) | 322.8(22) | |

| X2 religious (df) | 81.2 | 61.6(23) | 57.3(22) | 53.0*(23) | 47.9*(22) | |

| X2 less than HS (df) | 168.8 | 167.0(23) | 144.2*(22) | 82.1*(23) | 81.9(22) | |

| X2 HS (df) | 52.5 | 56.9(23) | 57.7(22) | 38.2*(23) | 38.2(22) | |

| − 2 LL | 68293.9 | 68343.3 | 88964.2 | 89010.0 | 86183.1 | 86233.0 |

*p < 0.05; ~ p < 0.10

The first column in Table 3 shows that women on average express less negative perceptions than men, as demonstrated in the descriptive analysis. As indicated in the second row of this model, religious individuals hold less negative perceptions of children, as expected. Similarly, university education is associated with more negative perceptions than is high school or some post-high school (non-university) education. However, no significant differences are found between people with university education and people with less than high school education. This is probably due to various reasons for seeing children as a burden: the highly educated might see them as interfering with career opportunities and personal freedom, while low-educated (probably also low income) individuals are likely more affected by the costs of children. Interestingly, those not in the labour force express more negative attitudes than those who work fulltime, while no significant differences are found between part-time and fulltime workers. Some of these differences probably reflect the economic costs of children, and even the special characteristics of persons not in employment (e.g. those who suffer from disabilities or other social problems). Lastly, married persons express less negative perceptions of children, and negative perceptions tend to decrease with age.

The second column in Table 3 adds coefficient estimates for country-level effects. The Chi-square statistics indicate an improvement of the model. Three macro-level factors have a statistically significant association with negative perceptions of children: length of paid parental leaves, the proportion of infants in day-care, and a country’s average level of religiosity. Unemployment rate has no significant relation to cross-country variation in negative perceptions. In line with our expectations, more generous parental leave and higher availability of day-care decrease the perception that children present social, personal, and economic barriers to their parents. Moreover, the average level of negative perception of children is lower in more religious countries. This seems to indicate that institutional contexts that support parents for raising children, together with normative contexts that emphasize traditional family values, are associated with reduced perceptions of children as a burden on their parents. Overall including the macro-level variables reduced country variation by 5%.

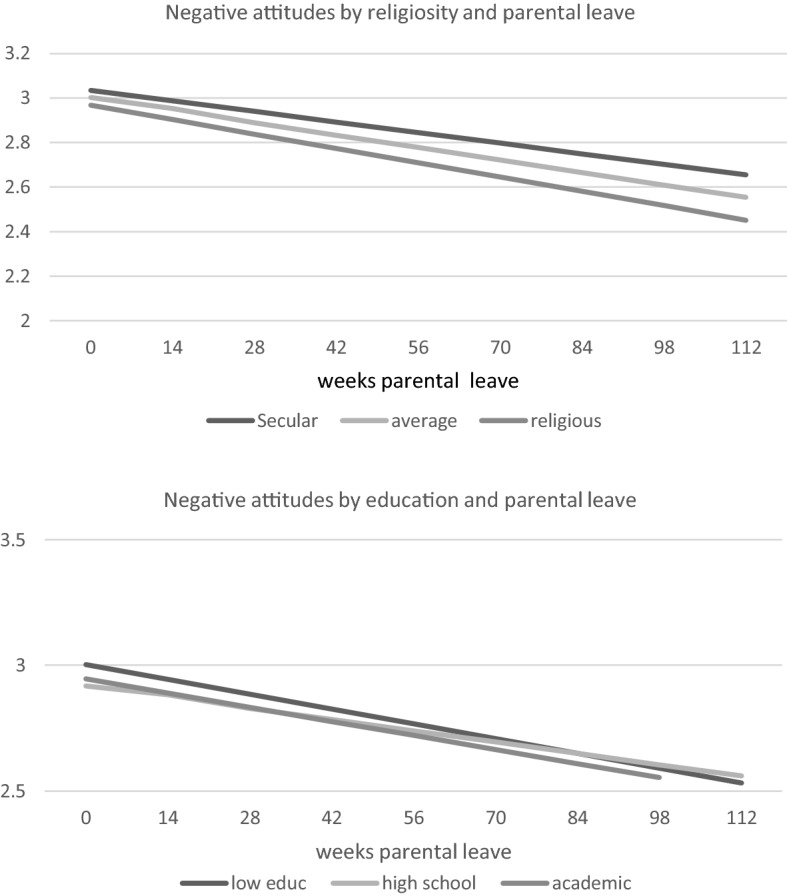

The last column in Table 3 adds to the model interactions between micro- and macro-level variables. The main variable found to interact with individual characteristics is the length of parental leave. The interaction coefficient modifies the relation between the negative attitudes towards children and two individual-level factors: religiosity and education. Specifically, in countries that provide more generous parental leave arrangements, the association between religiosity and negative attitudes is firmer, attesting to the relationships between culture and the way individuals perceive children. The first panel of Fig. 3 presents these relationships graphically, using the predicted values of negative perception by the level of religiosity (holding all other variables at their mean). It is evident that the gap between secular and more religious people in their attitudes towards children widens in an institutional context that supports children and families. This could indicate that when support for children reduces their costs, normative attitudes are more important in determining how individuals perceive children.

Fig. 3.

Predicted values of negative attitudes towards children by education (upper panel), religiosity (lower panel) and paid parental leave

At the same time, in a more supportive context people with high school education have less negative views on children. This may be because it is easier for them to combine work and family, or to cover the costs of having children. In other words, while the association is relatively weak, state support for parents is associated with smaller gaps among different educational groups. The second panel of Fig. 3 presents these relationships graphically, using the predicted values of negative perception for the three educational groups (holding all other variables at their mean). The figure clearly shows that educational differences disappear when parental leave is very generous.

Table 4 presents coefficient estimates for country- and individual-level effects on the three items that reflect positive perceptions of children. Because the variation at the macro-level is small, we included only one indicator at that level: paid parental leave, since the policy indicator is a focus of our theoretical interest, in both its association with attitudes and the interaction with gender and education.6 In the first model for each positive item, we concentrate on the effect of individual-level variables, and in the second model, we focus on the interactions between micro- and macro-level factors.

The effects of most of the individual-level characteristics are in line with our expectations, although there are interesting differences across measures (columns 1, 3, 5). Gender plays a part in explaining all three positive dimensions, but the effect is inconsistent across measures: women perceive children as a joy more than men, but they express less positive perceptions regarding children’s contribution to the family’s social standing and their role in supporting the family. More religious individuals have more positive perceptions. Also, respondents with a low education level (below high school) hold more positive views on children than people with university education. Those with high school education are in between, but the difference compared with university education is significant only for the first item (children as a joy). As for the control variables, fulltime employment decreases the positive perception of children on all measures, as compared to part-time employment. Also, those out of the labour force have more positive views than those working fulltime in the perception of children as contributing to the family’s social standing and their role in supporting the family. However, the difference between fulltime workers and those out of the labour force is not significant in the case of seeing children as a joy. Possibly those in part-time employment have more time to engage with children or choose this mode of employment because they are more family-oriented. Married people express more positive perceptions regarding the joy of raising children, but they are less positive than un-partnered people about seeing children as a source of support. Lastly, the perception of children as a joy and as enhancing their parent’s social standing tend to increase with age, while perceiving children as an important source of support for their elderly parents decreases with age.

Turning to the micro–macro-interaction model (columns 2, 4, 6), we see that paid parental leave has no significant relation with two of the items (children as a joy and children as a source of support), while in countries with more support for families there is also a higher tendency to perceive children as contributing to the family’s social standing (p = 0.075). More importantly, paid parental leave interacts with gender and education. As for gender, in all three indicators of positive attitudes we found a positive effect of paid leave on the gender coefficient. This means that in more supportive contexts, women’s perceptions regarding social support and social standing become more positive; therefore, gender differences decline. However, a supportive environment is associated with greater gender disparities in the case of seeing children as a joy, since women, who have more positive attitudes to begin with, have an even more positive perception in this setting. The same holds for education (except the indicator of children as a social support, where the coefficient is not significant): in countries with generous parental leave, the positive association between having low or intermediate education and perceiving children as a joy and as increasing social standing declines, narrowing the gaps among the three educational groups. Again, Fig. 4 presents these relationships, showing the decline in educational differences and the general increase in positive perceptions when parental leave is more generous.

Fig. 4.

Predicted values of positive attitudes towards children by education and paid parental leave

Discussion and Conclusion

This study has explored the way individuals perceive children, focusing on positive aspects (children as a source of joy and happiness, benefiting from children) as well as negative (children as costly and interfering with work and personal freedom). We examined individual- and county-level factors associated with these views, focusing in particular on the association of social policies with the perception of children as a burden.

Generally, we found much variation among countries in negative perceptions of children, but a relatively higher level of similarity in positive perceptions, especially regarding children as a source of happiness and joy. People in all countries exhibited stronger support for this perception than for other attitudes pertaining to the benefits or costs of having children. However, interesting differences appeared among individuals and countries.

As for individual-level characteristics, we found interesting gender differences: women perceived lower benefits of children in terms of their contribution to the social standing of the family and as a source of support for old age, as we expected (H1). Yet women experienced more joy seeing children grow up and they also expressed less negative attitudes—contrary to our expectations. Perhaps because men perceive themselves as the main providers for the family, they also perceive children as costly more than women do, while most women see children as more central to their identity (Cinamon and Rich 2002; Gaunt and Scott 2017). Also, most women may prefer to combine work and family, as Hakim (2002) argues, and therefore do not see themselves as the main providers or children as an obstacle to self-fulfilment. With regard to education and religiosity, our findings support our hypotheses (H2, H3) and are in line with previous studies (Gubernskaya 2010; Jones and Brayfield 1997; Yucel 2015): in general, university education increased negative attitudes and decreased positive attitudes, while religiosity decreased negative attitudes and increased positive ones.

Our main interest lay in explaining cross-country variation in attitudes towards children—the associations between macro-level factors, especially policy, as well as the interactions between micro- and macro-factors. In this regard, both the institutional support for children and working parents (weeks paid care and % children aged 0–2 in day-care) and the cultural environment (level of religiosity) proved to be important dimensions in explaining cross-country variation in negative perceptions of children.

An interesting result of this study concerns the relations between family-supportive policies, mainly parental leave, and the perceptions of children. Such policies, which are expanding in many countries, help parents deal with the costs and work burdens of children, as expected (H4). They are important because they provide a better way for parents to combine work and family and also reduce the costs of work interruptions, thus improving families’ economic conditions and economic stability. These policies have also been found to increase fertility at the macro (country)-level (Wesolowski and Ferrarini 2018). In the same vein, our findings indicate that such policies are associated with reduced negative sentiments regarding children. Moreover, while as expected we found that attitudes towards children varied by education and religiosity, the effect was conditioned by the level of supportive policies, as hypothesized (H7). Notably, these policies were found to be associated with reduced differences among educational groups in relation to children. The costs of children in terms of forgone opportunities in the labour market are especially high for the highly educated. The price of work interruptions is high for those who have high opportunity costs, and the entire family is affected. However, the economic costs of children might be more severe for individuals with low education (and low income), although as Lawson and Mace (2010) argued, those with greater resources also have higher investments in children. In both cases, when countries provide generous support for care work when children are young, the educational differences decline and at a certain level actually disappear. Likewise, as policies become more generous, educational differences in perceiving positive aspects of children decline (perceiving children as a joy and as increasing the family’s social standing). Though the relations between these perceptions and actual fertility are complex and beyond the scope of the current study, our findings could shed light on the association between policies and fertility for the entire population, as well as on how fertility is distributed across different educational groups.

That said, our findings also show that disparities correlated with religiosity become more pronounced in countries that support family work. This finding might indicate that when children are seen as less of a burden due to generous social support, the effect of ideology becomes much stronger than where economic considerations play a role in determining how children are perceived. So differences in attitudes between groups become more pronounced in a context where families can afford to have children, but women nonetheless encounter high costs if they enter the labour market. Generous parental leave, for example, may allow more religious families to maintain a gendered division of labour in which women do not work for a prolonged period, and hence, these families have much less negative views about children. However, other characteristics of such families may also be responsible for this result. Future studies should look more closely at the effect of religion and religiosity on the perception of children.

Second, in line with our hypothesis (H5), we found that in an environment that culturally supports traditional family values, attitudes towards children were less negative. Perhaps parents ascribe greater importance to family and childbirth, or other institutional arrangements favour families, so that children are less perceived as a burden.

Third, contrary to our expectation (H6), economic conditions in the country as indicated by the unemployment rate did not have a significant relation with the negative attitudes, so they are less consequential for perception of the costs of children. That said, we did find that in more affluent country’s (as measured by the country’s GDP, see Appendices A2, A3 on-line) the negative aspects of having children are less pronounced. Indeed, policies that support child-rearing and working families are more generous in more affluent countries. These findings were robust even after excluding countries which are richer but less supportive of families, such as the USA. We may conclude that the normative environment and family-supportive policies are important macro-level characteristics in explaining variations in perceptions of children, while the economic conditions might play an indirect role in affecting this variation.

This study is not without its limitations. The perception of children is influenced by individuals’ life stage, by whether they already have children, and by norms and institutions not measured in this study. Also, with only 24 countries included in the analysis, it was difficult to assess the effect of other indicators that might affect the perception of children or might account for the effect of other indicators. For example, countries that provide high support for the family may also have lower levels of inequality and high levels of GDP. It is not easy to discern these effects, and future studies should incorporate a wider selection of countries so as to capture macro-level effects more accurately. However, beyond these shortcomings, our study highlights inconsistencies and discrepancies regarding the two aspects of attitudes towards children. On the one hand, there is general consensus and agreement that children are important and that they constitute a major source of happiness and support for their parents. On the other hand, perceptions of children as a burden vary and are associated with social policies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Israel Science Foundation Grant No. 1377/15. We would like to thank Efrat Herzberg for her valuable research assistance.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This solution was also confirmed by a factor analysis (not shown here).

Length of paid parental leave might affect the age at which children participate in day-care. A more nuanced measure of childcare participation (e.g., at age 1–2) would be better; however, such a measure is not available in the OECD database.

For each country, we calculated the average level of self-reported religiosity (attendance at religious services, as outlined above) ranging from 1—secular to 7—highly religious.

GDP, for example, is highly correlated with the percentage of children in day-care and other measures. Countries with low GDP are mainly former socialist countries in which maternity leave is generous, but the level of participation in day-care is lower. Models including the GDP (excluding the policy measures) indicate a significant effect of GDP on negative attitudes (namely, in countries with higher GDP attitudes are less negative) and on the perception of children as a joy (higher GDP is associated with less positive attitudes). There were also significant interactions with education and gender in affecting the perception that children contribute to the social standing of the family. In terms of model fit, there are minor differences between models. These models can be seen in an online appendices A2 and A3.

Bryan and Jenkins (2015) argue that there might be a possible bias in the estimates when the dataset contains a large number of individuals embedded in a relative small number of countries, as is the case with the current dataset. However, they point out that HLM corrects for these possible biases in the estimation.

In preliminary analyses, we tested the statistical effect of each of the other indicators. The relationships were not significant. The only exception was GDP (as mentioned above), which is negatively associated with the perception of children as a joy.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Haya Stier, Email: haya1@tauex.tau.ac.il.

Amit Kaplan, Email: amitka@012.net.il.

References

- Aassve A, Arpino B, Balbo N. It takes two to tango: Couples’ happiness and childbearing. European Journal of Population. 2016;32(3):339–354. doi: 10.1007/s10680-016-9385-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abendroth A-K, Huffman ML, Treas J. The parity penalty in life course perspective: Motherhood and occupational status in 13 European countries. American Sociological Review. 2014;79:993–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Adsera A. Where are the babies? Labor market conditions and fertility in Europe. European Journal of Population. 2011;27:1–32. doi: 10.1007/s10680-010-9222-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal A, Purushotham A, Sullivan R. The state of Europe’s fertility: Causes, consequences & future policies. European Journal of Social Sciences. 2013;40(2):217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Barber JS. Ideational influences on the transition to parenthood: Attitudes toward childbearing and competing alternatives. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2001;64(2):101–127. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. A treatise on the family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Gernsheim E. Reinventing the family: In search of new lifestyles. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi S. Maternal employment and time with children: Dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography. 2000;37(4):401–414. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan ML, Jenkins SP. Multilevel modelling of country effects: A cautionary tale. European Sociological Review. 2015;32(1):3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Budig MJ, England P. The wage penalty for motherhood. American Sociological Review. 2001;66:204–225. [Google Scholar]

- Budig MJ, Hodges MJ. Differences in disadvantage: Variation in the motherhood penalty across white women’s earnings distribution. American Sociological Review. 2010;75(5):705–728. [Google Scholar]

- Budig MJ, Misra J, Boeckmann I. The motherhood penalty in cross-national perspective: The importance of work–family policies and cultural attitudes. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society. 2012;19:163–193. [Google Scholar]

- Cha Y, Weeden KA. Overwork and the slow convergence in the gender gap in wages. American Sociological Review. 2014;79:457–484. [Google Scholar]

- Cinamon RG, Rich Y. Gender differences in the importance of work and family roles: Implications for work-family conflict. Sex Roles. 2002;47:531–541. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke LP. Gendered parenthood penalties and premiums across the earnings distribution in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. European Sociological Review. 2014;30(3):360–372. [Google Scholar]

- Craig L, Powell A, Smyth C. Towards intensive parenting? Changes in the composition and determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ time with children 1992–2006. British Journal of Sociology. 2014;65(3):555–579. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekert-Jaffe O, Stier H. Normative or economic behavior? Fertility and women’s employment in Israel. Social Science Research. 2009;38:644–655. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England P. Gender inequality in the labor market: The role of motherhood and segregation. Social Politics. 2005;12:264–288. [Google Scholar]

- England P. The gender revolution: Uneven and stalled. Gender & Society. 2010;24:149–166. [Google Scholar]

- England P, Bearak JM, Budig J, Hodges MJ. Do highly paid, highly skilled women experience the largest motherhood penalty? American Sociological Review. 2016;81(6):1161–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G, Billari FC. Re-theorizing family demographics. Population and Development Review. 2015;41(1):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett JT. The value and cost of the first child. In: Miller WB, Newman LF, editors. The first child and family formation. Carolina Population Center: Chapel Hill; 1978. pp. 244–265. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett JT. The value of children and the transition to parenthood. Marriage and Family Review. 1988;12:11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg, F. F., Kennedy, S., Mcloyd, V. C., Rumbaut, R. G., & Settersten R. A. (2004). Growing up is harder to do. Contexts, pp. 33–41.

- Gash V. Preference or constraint? Part-time workers’ transitions in Denmark, France and the United Kingdom. Work, Employment & Society. 2008;22(4):655–674. [Google Scholar]

- Gash V. Sacrificing their careers for their families? An analysis of the family pay penalty in Europe. Social Indicators Research. 2009;93(3):569–586. [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt R, Scott J. Gender differences in identities and their socio-structural correlates: How gendered lives shape parental and work identities. Journal of Family Issues. 2017;38(13):1852–1877. [Google Scholar]

- Glass J, Anderson MA, Simon RW. Parenthood and happiness: Effects of work-family reconciliation policies in 22 OECD Countries. American Journal of Sociology. 2016;122(3):886–929. doi: 10.1086/688892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornick J, Meyers M. Families that work: Policies for reconciling parenthood and employment. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gubernskaya Z. Changing attitudes toward marriage and children in six countries. Sociological Perspectives. 2010;53(2):179–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim C. Lifestyle preferences as determinants of women’s differentiated labor market careers. Work and Occupations. 2002;29(4):428–459. [Google Scholar]

- Hashiloni-Dolev Y. Cultural differences in medical risk assessments during genetic prenatal diagnosis: The case of sex chromosome anomalies in Israel and Germany. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2006;20(4):469–486. doi: 10.1525/maq.2006.20.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henz U. Gender roles and value of children: childless couples in East and West Germany. Demographic Research. 2008;19:1451–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman LW, Hoffman ML. The value of children to parents. In: Fawcett JT, editor. Psychological perspectives on population. New York: Basic Books; 1973. pp. 19–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman LW, Thornton A, Manis JD. Value of children to parents in the United States. Journal of Population. 1978;1(2):91–131. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart R. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart R. The silent revolution: Changing values and political styles among western publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart R, Baker WE. Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review. 2000;65(1):19–51. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organization Geneva (2010). Labour statistics database.

- Jones RK, Brayfield A. Life’s greatest joy? European attitudes toward the centrality of children. Social Forces. 1997;75(4):1239–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Kalwij A. The impact of family policy expenditure on fertility in Western Europe. Demography. 2010;47(2):503–519. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman G, Goldscheider F. Do men “need” a spouse more than women? Perceptions of the importance of marriage for men and women. Sociological Quarterly. 2007;48(1):29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lavee E. The neoliberal mom: How a discursive coalition shapes low-income mothers’ labor market participation. Community, Work & Family. 2016;19(4):501–518. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson DW, Mace R. Optimizing modern family size trade-offs between fertility and the economic costs of reproduction. Human Nature. 2010;21:39–61. doi: 10.1007/s12110-010-9080-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson DW, Mace R. Parental investment and the optimization of human family size. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2011;366(3):33–343. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R. The second demographic transition in Western countries: An interpretation. In: Mason KO, Jensen AM, editors. Gender and family change in industrialized countries. Oxford: Clarendon; 1995. pp. 17–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R. The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review. 2010;36(2):211–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liefbroer AC. The impact of perceived costs and rewards of childbearing on entry into parenthood: Evidence from a panel study. European Journal of Population. 2005;21:367–391. [Google Scholar]

- Liefbroer AC, Billari FC. Bringing norms back in: A theoretical and empirical discussion of their importance for understanding demographic behaviour. Population, Space and Place. 2010;16:287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Liefbroer A, Rijken R. The association between Christianity and marriage attitudes in Europe. Does religious context matter? European Sociological Review. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Mace R. The cost of children. Nature. 2013;499(4):32–33. doi: 10.1038/nature12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel H, Semyonov M. Family policies and gender gaps. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:949–967. [Google Scholar]

- Merz E-M, Liefbroer AC. The attitude toward voluntary childlessness in Europe: Cultural and institutional explanations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:587–600. [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen, A., Rotkirch, A., Szalma, I., Donno, A., & Tanturri, M. (2015). Increasing childlessness in Europe: Time trends and country differences. Families and Societies Working Paper Series, 33.

- Misra J, Budig M, Boeckmann I. Work-family policies and the effects of children on women’s employment hours and wages. Community, Work, and Family. 2011;14(2):139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Han S-K. Gendered careers: A life course perspective. In: Hertz R, Marshall NL, editors. Working families: The transformation of the American Home. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2001. pp. 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nauck B, Klaus D. The varying value of children. Current Sociology. 2007;55(4):487–503. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SK, Kushlev K, Lyubomirsky S. The pains and pleasures of parenting: When, why, and how is parenthood associated with more or less well-being? Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140(3):846–895. doi: 10.1037/a0035444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD family database. (2005a). https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=54760.

- OECD family database. (2005b). https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF3_2_Enrolment_childcare_preschool.pdf.

- Pfau-Effinger B. Development of culture, welfare states and women’s employment in Europe. Farnham: Ashgate; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T, Skirbekk V, Philipov D. Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review. 2011;37(2):267–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stier H, Lewin-Epstein N, Braun M. Welfare regime, family-supportive policy, and women’s employment along the life course. American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106:1731–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Stier H, Lewin-Epstein N, Braun M. Work-family conflict in comparative perspective: The role of social policies. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2012;30(2012):265–279. [Google Scholar]

- Surkyn J, Lesthaeghe R. Value orientations and the second demographic transition (SDT) in northern, western, and southern Europe: An update. Demographic Research. 2004;3(3):45–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Lowry D. Materialism, gender, and family values in Europe. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 2011;42(2):131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Trent K, South SJ. Sociodemographic status, parental background, childhood family structure, and attitudes toward family formation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1992;54:427–439. [Google Scholar]

- Uunk W, Kalmijn M, Muffels RJA. The impact of young children on women’s labour supply: A reassessment of institutional effects in Europe. Acta Sociologica. 2005;48(1):41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Lippe T, van Dijk L. Comparative research on women’s employment. Annual Review of Sociology. 2002;28:221–241. [Google Scholar]

- Wesolowski K, Ferrarini T. Family policies and fertility: Examining the link between family policy institutions and fertility rates in 33 countries 1995-2011. International Journal of Sociology and Social policy. 2018;38(11/12):1057–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker TA, Furlow CF. The comparison of model selection criteria when selecting among competing hierarchical linear models. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods. 2009;8(1):173–193. [Google Scholar]

- Yucel D. What predicts egalitarian attitudes towards marriage and children: Evidence from the European Values Study. Social Indicator Research. 2015;120:213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Zelizer VA. Pricing the priceless child: the changing social value of children. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.