Abstract

As more and more countries consider expanding public childcare provision, it is important to have a comprehensive understanding of its implications for families. This article adds to the existing literature by investigating the effect of publicly funded childcare on parental subjective well-being. To establish causality, I exploit cut-off rules introduced following the implementation of a legal claim to childcare in Germany. The results suggest that childcare provision strongly increases the life satisfaction of mothers who were previously constrained by the lack of childcare supply. The effect is more pronounced for mothers with higher labour market attachment. The coefficients for fathers are smaller and not statistically significant. As potential mechanisms, a wide range of time-use and labour market outcomes are explored. This shows that mothers indeed shift time from non-market activities to formal work in response to childcare eligibility, resulting in direct and indirect pecuniary and non-pecuniary returns to maternal life satisfaction. The findings shed light on key issues of work–family reconciliation and stress the importance of considering subjective well-being measures in family policy evaluations.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10680-019-09526-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Public childcare, Life satisfaction, Work–life balance, Maternal employment

Introduction

In recent years, the provision of formal childcare has emerged as an issue of major public concern. Policymakers in several countries have agreed on reforms to expand access to affordable and good-quality public childcare (OECD 2011), in particular in Europe (European Commission 2009). Despite the widespread interest, from both the public and policymakers, not all consequences of the expansion of public childcare provision are well understood. Existing research focuses mainly on the impact on objective measures such as maternal employment and child development (see overviews in Bauernschuster and Schlotter 2015; Duncan and Magnuson 2013). Research on how public childcare provision impacts the subjective dimension of family well-being is sparse. However, there is an increasing awareness that these measures are important in policy evaluations because they capture information that is beyond the reach of objective measures and revealed preferences (e.g. OECD 2015; Kőszegi and Rabin 2008; Dolan and White 2007).1

In general, it is expected that expanding childcare provision and, hence, maternal labour supply choices would contribute to parental well-being, simply because families face a greater choice set and can select according to their preferences. However, previous studies show that some childcare policies have unintended negative side effects, causing mothers to feel more stressed, depressed, and less satisfied with their life (e.g. Baker et al. 2008; Brodeur and Connolly 2013; Herbst and Tekin 2014). Similarly, a few recent studies suggest that women’s gains in the labour market along several objective outcome dimensions, including their labour force participation and earnings, might not necessarily translate into improvements in subjective well-being (see discussions in Stevenson and Wolfers 2009; Bertrand 2011, 2013). Hence, the subjective dimension of parental well-being constitutes an important tool to evaluate hard-to-quantify costs and benefits. Neglecting it could result in an important aspect in the debate on childcare and family policies being overlooked.2

The purpose of this paper is to examine whether the provision of publicly funded childcare impacts parental subjective well-being in Germany. This contribution is particularly interesting given that Germany is a country that has long been characterized by very low childcare attendance rates and maternal employment rates, mainly due to severe supply side restrictions on the childcare market (BMFSFJ 2005; Wrohlich 2008) and despite the fact that women are highly educated. The analysis is based on national representative panel data from the German Socio-Economic Panel study (SOEP), using the well-established global life satisfaction measure as the main outcome. The results suggest that publicly funded childcare significantly increases the life satisfaction of mothers who were previously constrained by the lack of childcare supply. The effect is more pronounced for mothers with stronger labour market attachment, suggesting that the incongruence between actual and desired employment status, due to the lack of childcare supply, is an important determinant of maternal life satisfaction.3 Fathers seem to be affected less in their life satisfaction. An additional contribution of this article is to provide empirical evidence on the mechanisms driving the effect on subjective well-being, rather than solely relying on theoretical arguments. To do this, a wide range of time-use and labour market outcomes are explored. The results indeed show that once mothers are eligible for childcare, they shift time from non-market activities to formal work, resulting in a large increase in labour force participation and earnings. Noteworthy, almost the entire employment effect is driven by regular part-time employment, rather than full-time or marginal employment. Fathers, however, do not exhibit any changes in labour market outcomes, which is consistent with men having higher elasticities of labour supply than women.

In the empirical analysis, the endogeneity of childcare attendance is addressed in a fuzzy Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD) that exploits a discontinuous increase in the probability of attending childcare. This discontinuity is induced by cut-off rules that were implemented after the introduction of a legal claim to (half-day) publicly funded childcare for all children above the age of three, starting on 1 January 1996. Although this legal claim was meant to eliminate any supply side restrictions on the childcare market that many families previously faced, a large number of municipalities could not immediately provide sufficient places. To reduce the pressure of demand and to give municipalities time to adapt to the new law, municipalities were allowed to establish cut-off rules and fixed childcare starting dates. The cut-off rules implied that some children cannot enter childcare by their third birthday, but instead have to wait until the year after they turned three to start formal childcare.4 The validity of using the cut-off rules as a source of exogenous variation in childcare attendance is supported by a set of placebo treatment tests and robustness checks. In particular, I carefully assess whether direct age effects confound the analysis by testing for discontinuities in well-being in periods before the cut-off rules were implemented. Furthermore, I show that the results are not sensitive to bandwidth or functional form assumptions and demonstrate that other covariates evolve continuously around the cut-off.

The findings of this study contribute to a small, but growing, literature on the impact of childcare policies on parental subjective well-being.5 The most extensively analysed reform in the economic literature is the universally accessible childcare subsidy program in Quebec, Canada. Baker et al. (2008) show that this so-called $5-per-day reform not only significantly increases maternal labour supply but also has adverse effects on various child and family well-being outcomes, including parental life satisfaction, paternal self-reported health, maternal depression, and work–family conflicts. Using a different data set and method, the follow-up study by Brodeur and Connolly (2013) also points towards a small negative reform effect on parental life satisfaction. However, they show that the effect is very heterogeneous, suggesting that subtle mechanisms are at play (see also Kottelenberg and Lehrer 2013).6 Evidence from a targeted childcare subsidy program provided by Herbst and Tekin (2014) in the USA also suggests that childcare subsidies reduce maternal physical and mental health and result in poorer interactions between parents and children. However, in the US setting subsidies are only granted to disadvantaged families, conditional on mothers being in employment, job training, or education (Herbst and Tekin 2014). Another important difference between the Canadian as well as the US setting and the setting in this paper is the source of variation used for identification, i.e. the variation exploited for identification in the other studies comes from reducing childcare prices rather than from abandoning the rationing of childcare provision in general. Hence, particular families with lower socio-economic background comply with these reforms.

Consequently, more closely related to this paper are correlation-based studies by Yamauchi (2010), Schober and Stahl (2016) and Schober and Schmitt (2017), who use variation in the local availability of childcare to study the associations with parental well-being. For Australia, Yamauchi (2010) shows that an increase in local childcare availability in Australia is associated with an increase in the subjective well-being of parents and a decrease in perceived search costs, in particular in communities with an initial low number of available childcare places. For Germany, studies by Schober and Stahl (2016) and Schober and Schmitt (2017) point towards a modest positive association between childcare provision for children under the age of three and the well-being of mothers. More broadly, this paper also adds to the cross-country studies which stress the key role of institutional resources and support provided to parents in explaining the large disparities in parents’ subjective well-being across countries (e.g. Pollmann-Schult 2018; Glass et al. 2016).

In short, there are two main contributions of this paper: first, I analyse well-being effects of a childcare policy that potentially impacts all families, not only families with low household income. Second, my identification strategy allows me to estimate causal effects in this setting.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the institutional setting in Germany, in particular the analysed childcare reform. Section 3 introduces the data set, Sect. 4 outlines the empirical strategy and Sect. 5 reports the main findings and discusses potential mechanisms and the robustness. Section 6 concludes.

Institutional Setting

In recent years, there has been strong political effort to increase public childcare provision in Germany. Among the most prominent and earliest reforms was the introduction of a legal claim to a place in (half-day) publicly funded childcare for all children above the age of three until school entry. The legal claim became effective from 1 January 1996, applying to almost all existing childcare institutions. This is because in Germany—in contrast to other industrialized countries—most childcare places are publicly funded and provided by the municipalities themselves or by non-profit organizations such as churches and welfare associations (e.g. Spieß 2008).7 As a consequence of the legal claim, childcare attendance rates of 3 and 4 year olds in Germany increased sharply. As shown in Figure A1, in 1996 the share of children attending childcare in West Germany amounted to only 30% for 3-year, 60% for 4-year, and around 90% for 5- and 6-year-old children, while in East Germany these numbers range from 80 to 95% (BMFSFJ 2005, 196–199). In 2005, the latest period considered in the analysis, already around 55% of children aged 3 and 85% of 4-year-old children attended childcare.

Despite this increase in childcare attendance rates, there were difficulties in implementing the legal claim to childcare. The law was passed at the federal level, while the implementation and financing of the legal claim were up to the states and municipalities.8 Some municipalities, in particular those that previously only provided publicly funded childcare to a small fraction of children, faced severe resource and capacity constraints and simply could not provide the necessary places right away. As a consequence, the German Federal Parliament (Deutscher Bundestag) adopted a legislative initiative proposed by the Federal Council (Bundesrat) that allowed the municipalities to (voluntarily) introduce cut-off rules and fixed childcare starting dates (see also Bauernschuster and Schlotter 2015; Schlotter 2011). The start of a childcare year usually coincides with the start of a school year, which in Germany differs by state and year. Usually, it lies between July and September (Kultusminister Konferenz 2016). The cut-off rules stated that a child is not necessarily eligible for a place in publicly funded childcare immediately at the point of his or her third birthday, but rather only becomes eligible to claim a childcare place at the start of the childcare year following his or her third birthday. Thus, if children turned three shortly after the cut-off date, they had, at worst, to wait another year to enter childcare. With this, some of the demand pressure was relieved, giving struggling municipalities more time to adapt to the new law. The cut-off rules were meant to be temporary, and the transition period was planned to finish by the end of 1998. However, many municipalities continued to apply the cut-off rules over long periods of time (BMFSFJ 2005).

The main goal of the reform was to foster the reconciliation of work and family life, thereby increasing the labour supply choices of mothers and decreasing gender inequalities while also increasing the well-being of children and parents (Schmidt 2006). In Germany, female and, in particular, maternal employment rates have been traditionally low, despite German women being highly educated. One major explanatory factor was the severe supply side restrictions on the childcare market (BMFSFJ 2005; Wrohlich 2008). In 1996, the share of mothers with children under the age of 18 in employment amounted to 55%; a number that was considerably lower for mothers with children under the age of six. This number increased to 59% in 2004. However, the vast majority of mothers (more than three-quarters in 2004) work in part-time. In particular, mothers with children under the age of six exhibit very low full-time employment rates (BMFSFJ 2012).

Another characteristic of the German childcare market is that fees are usually income-dependent and heavily subsidized. Subsidizes cover on average 80% of the childcare fees, in some states even up to 100% for certain age groups and households (Statistisches Bundesamt 2004; Schmitz et al. 2017). The amount of fees paid by parents is below the OECD average (OECD 2006).9 Furthermore, parental leave regulations are generous. Since 1986, parents have the right to a job-protected leave for up to 36 months after childbirth. In addition, the Maternity Protection Act of 1968 enforces a period of six weeks of compulsory leave before birth and eight weeks afterwards, during which mothers receive their full average net-labour earnings.

Data

To examine the impact of publicly funded childcare on parental subjective well-being, I use data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). The SOEP is a national representative annual panel study of private households in Germany. It was first implemented in 1984 in West Germany and later extended to East Germany. The panel data set covers about 30,000 respondents from 12,000 households (Wagner et al. 2007).

In the main analysis, the sample is limited to parents whose youngest child was exposed to the cut-off rules that were temporarily introduced after the legal claim to childcare in 1996. The first cohort affected by the cut-off rules was the cohort of children born in 1992. Children born after 2000 were exposed to a much lesser extend, i.e. the first-stage (jump at cut-off) is much weaker for these birth cohorts. To circumvent weak instrument issues, I restrict the sample to children born between 1992 and 2000. Observations with missing values in the main outcome variable or important covariates are dropped from the analysis. The main sample consists of 14,730 observations from 7897 mother–child observations (1743 mother–child pairs) and 6833 father–child10 observations (1593 father–child pairs). For additional robustness checks, I also use data from older cohorts. Furthermore, I link the SOEP households to administrative records on childcare supply at the district level (Statistisches Bundesamt 2012) to gain some deeper knowledge about the application of cut-off rules in post-reform periods in Germany.

Parents’ Subjective Well-Being

The SOEP has a long tradition of collecting subjective well-being data and is used extensively in the well-being literature (e.g. Ferrer-i Carbonell and Frijters 2004; Frijters et al. 2004). The main outcome variable in the analysis of this study is a global life satisfaction measure based on the following question:

In conclusion, we would like to ask you about your satisfaction with your life in general. Please answer according to the following scale: 0 means completely dissatisfied and 10 means completely satisfied. How satisfied are you with your life, all things considered?

Neither the wording of this question, nor its relative position in the questionnaire changed over the period under study, which mitigates concerns of comparability and item-order effects (Schwarz and Strack 1999). Furthermore, the global life satisfaction measure is shown to have a high face validity and strong robustness to potential biases (e.g. Diener et al. 1985) which justifies its widespread use in the literature. In the analysis, life satisfaction is handled as a cardinal variable11 and I use only the within variation in parental life satisfaction by including individual fixed effects. As shown by Ferrer-i Carbonell and Frijters (2004), the inclusion of individual fixed effects is very important, but neglecting the interpersonal ordinality of the variable by assuming cardinality is of minor concern (see also Riedl and Geishecker 2014).

Childcare Attendance and Eligibility Status by Cut-Off Rules

In the SOEP, the household head provides detailed information on childcare arrangements and the child’s month and year of birth. Information on the exact date of the fixed childcare start can be obtained from the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (Kultusminister Konferenz 2016). These data are matched via the current state of residency to the SOEP households. Given this information, it is possible to compute the exact age of the child at the time when the last childcare year started and, hence, determine eligibility status by the cut-off rules.

Since the SOEP does not ask the respondent when the child first entered childcare, but rather if the child attends childcare at the time of the interview, one must assume that children who are observed to be in childcare at the time of the interview started childcare immediately at the beginning of a childcare year.12 Most interviews are carried out in spring, i.e. roughly half a year after childcare starts. Based on the DJI Kinderpanel data, which cover the exact month of entry into childcare, Schlotter (2011) shows that more than half of the children of the relevant birth cohorts indeed enter childcare in the month in which school starts in their state of residency. In all other months, childcare entrance is uniformly distributed and very low (around 5% per month).

One argument by Bauernschuster and Schlotter (2015) that is actually in favour of the childcare measure in the SOEP, i.e. in favour of not using a retrospective measure on the exact date when the child first entered childcare, is that it gives mothers the chance to find a suitable employment in between the start of the childcare year in August/September and the time of the interview. Furthermore, it avoids misreporting due to a settling-in-period that usually takes place during the first months of childcare in Germany. Also, it avoids measurement errors or recall errors in childcare attendance that can be attributed to a retrospective measure (Garces et al. 2002), which tends to increase as respondents are asked to think further back in time (Ebbinghaus 1894).

Control Variables

To examine the robustness of the results and to increase efficiency, I use an extensive set of time-variant covariates on the individual and household levels. Specifically, this includes detailed information on marital status (married, single, widowed, divorced, married but separated), cohabitation status, age of the parent in years (linear and quadratic), father’s labour income, state of residence and the number of children in the household.13 Most of these variables are shown to be important determinants of subjective well-being (e.g. Dolan et al. 2008). In addition, all specifications include a set of (separate) year and seasonal dummies. As a robustness check, I also include self-reported health as an additional control variable. It is important not to include covariates that are potentially endogenous to the treatment, e.g. labour market outcomes of the mother. Instead, they are explored as additional outcomes and potential mechanisms.

Mechanisms

SOEP offers various time-use measures to empirically investigate the mechanisms driving the effect of childcare attendance on the subjective well-being of parents (for a detailed discussion of mechanisms see Sect. 5.3). The respondent is typically asked how many hours she or he spends on various activities during a typical workday. In this study, I focus on hours devoted to caring for the own child,14 housework, time spent on the job or training, errands, and leisure or hobbies. Furthermore, labour market outcomes, such as the employment status, gross labour income, and net household income, are considered as potential mechanisms. Since the employment-driven effects of public childcare provision on well-being may depend on the characteristics and quality of the job, I differentiate between regular full-time, regular part-time and marginal employment.

Table 1 presents summary statistics of the maternal life satisfaction variable and other covariates. The corresponding statistics with information for fathers is shown in Table A1 in Online Appendix. It is evident that mothers on average report slightly higher life satisfaction (7.128) than their partners (7.074). The majority of mothers are married. Comparing time-use statistics clearly shows the prevalence of the traditional division of labour within households. Mothers spend much more time on childcare and household work, but less on formal work. Only about 40% of mothers participate in the labour market, the majority in part-time positions.

Table 1.

Summary statistics

| Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main variables | |||||

| Maternal life satisfaction | 7.128 | 1.620 | 1 | 10 | 7897 |

| Childcare attendance | 0.432 | 0.495 | 0 | 1 | 7897 |

| Mother’s labour market outcomes | |||||

| Labour force participation | 0.401 | 0.490 | 0 | 1 | 7897 |

| Full-time employment | 0.106 | 0.308 | 0 | 1 | 7897 |

| Part-time employment | 0.217 | 0.412 | 0 | 1 | 7897 |

| Marginal employment | 0.077 | 0.267 | 0 | 1 | 7897 |

| Gross labour income | 494.465 | 1082.263 | 0 | 45,000 | 7881 |

| Household net income | 2375.579 | 1285.108 | 177 | 23,000 | 7562 |

| Maternal time use | |||||

| Time use: childcare | 7.095 | 3.579 | 0 | 12 | 7887 |

| Time use: job, training | 2.199 | 3.313 | 0 | 12 | 7794 |

| Time use: housework | 3.733 | 2.041 | 0 | 12 | 7798 |

| Time use: leisure and hobbies | 1.391 | 1.326 | 0 | 12 | 7605 |

| Time use: errands | 1.447 | 0.800 | 0 | 11 | 7782 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Number of children in household | 1.916 | 0.894 | 0 | 6 | 7897 |

| Age of mother | 32.840 | 5.276 | 17 | 51 | 7897 |

| Married | 0.820 | 0.384 | 0 | 1 | 7897 |

| Cohabiting | 0.911 | 0.284 | 0 | 1 | 7897 |

| Years of education mother | 11.779 | 2.414 | 7 | 18 | 7897 |

| East Germany | 0.160 | 0.367 | 0 | 1 | 7897 |

The sample is restricted to mothers with a youngest child born between 1992 and 2000. Observations with missing data on the main outcome or covariates are dropped from the analyses. Columns 1 and 2 give the overall mean and standard deviation of the variable. Columns 3 and 4 provide the minimum and maximum value, and column 5 gives the number of observations

Source: SOEP v31, own calculation

Empirical Strategy

There are two major sources of endogeneity that impose a potential threat to the identification of a causal effect of public childcare on parental subjective well-being: omitted variables and reverse causality. Omitted variable bias might evolve due to observed or unobserved characteristics of parents that influence both childcare attendance and parental subjective well-being. These systematic differences can either be driven by time constant (e.g. personality traits) or time-varying characteristics (e.g. maternal employment or marital status). In Germany, studies show that selection indeed evolves on the demand and supply side of the childcare market (e.g. Spieß et al. 2002, 2008; Fuchs and Peucker 2006). The second source of bias is reverse causality. It might be that the subjective well-being of parents itself affects the decision to send the child to childcare, e.g. if struggling parents who exhibit lower levels of well-being are more likely to send the child to childcare. These endogeneity problems cannot be fully accounted for by the inclusion of confounding factors as control variables in the analysis since many remain unobserved or vary over time. Hence, applying selection-on-observables techniques, such as matching or regression control estimations, or fixed effects estimation, cannot account for all sources of endogeneity.

Using a fuzzy Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD) circumvents these issues. The general idea of a fuzzy RDD is to exploit a discontinuity in the probability of treatment as an instrument for the actual treatment status (Imbens and Lemieux 2008). Thereby, the treatment eligibility is determined by an assignment variable. Individuals who are above a certain threshold of the assignment variable are eligible to treatment, whereas individuals below the threshold are not. The threshold is typically set exogenously by institutional rules. Under some weak assumptions discussed in the following, a discontinuity in the outcome variable at the threshold, rescaled by the jump at the cut-off in the probability of treatment, can be interpreted as the causal effect of the treatment on the complier population, i.e. the local average treatment effect (LATE). In the analysis of this article, the LATE translates to the effect of childcare attendance on the subjective well-being of parents who previously faced strong restrictions in access to publicly funded childcare, but send their child to childcare if they are entitled to do so by the cut-off rules. More specifically, the exact age of the child at the time when the last childcare year started is used as the assignment variable for childcare eligibility. All children exceeding the cut-off age, i.e. who were older than 36 months at the time when the last childcare year started, have the right to a place in publicly funded childcare at the time of the interview. Children turning three just after the childcare starting date, on the other hand (at worst), must wait another year before becoming eligible for childcare. Of course, not all families perfectly complied with the cut-off rules, making this a fuzzy RDD. Some parents were able to place their child in childcare at a younger age—either at the start of a childcare year or during the course of the year—while others preferred to care for their child at home. The empirical strategy exploits the same source of exogenous variation as Bauernschuster and Schlotter (2015) and Schlotter (2011).

Formally, the baseline first-stage (Eq. 1) and second-stage (Eq. 2) regressions of the estimated fuzzy RD model look as follows:

| 1 |

| 2 |

The binary indicator is equal to 1 if the child of parent i is at the right-hand side of the discontinuity at the time of the interview in year t, i.e. older than 36 months at the time when the last childcare year started, and 0 otherwise. In the first stage (Eq. 1), this indicator is regressed on the binary treatment variable , which is equal to 1 if the child attends childcare at the time of the interview, and 0 otherwise. In the second stage (Eq. 2), the exogenous variation in childcare attendance at the cut-off is regressed on the subjective well-being () of parents. and are individual fixed effects and and are the idiosyncratic error terms of the first and second stages, respectively. The baseline model includes a quadratic age polynomial and of the assignment variable (), centred at the threshold ( months) to simplify interpretation. By interacting the polynomials with the instrument , the direct age effects are allowed to vary on either side of the threshold. The baseline model uses the full sample of children aged 0 to 6 years, as suggested by formal and informal model specification tests. estimates the share of families who act in compliance with the cut-off rules and estimates the LATE, i.e. the effect of childcare attendance on the subjective well-being of parents who send their child to childcare because they are entitled to do so by the cut-off rules. The reduced form coefficients, i.e. regressing the right-hand side of Eq. (1) directly on the outcome (), yield intention-to-treat effects (ITT) and will also be reported in the following.

Results

First-Stage Results

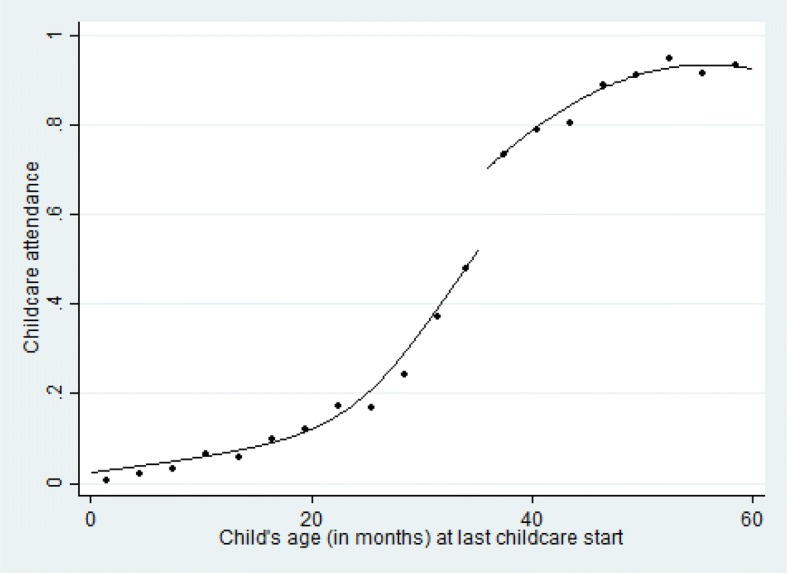

Figure 1 plots childcare attendance rates at the time of the interview by the child’s age at the time of the last childcare start. The dots indicate averages over bins of 3 months. It is evident that childcare attendance, in general, increases smoothly with the age of the child, closely following a quadratic specification in age. However, at the 36-months cut-off there is clear discontinuous jump of about 16 percentage points. This discontinuity at the threshold corresponds to an increase in childcare attendance by more than 28%. There is no evidence for a discontinuity at any other point along the age distribution. Figure A2 plots the share of children who enter childcare for the first time for each age group. It supports the interpretation of Fig. 1 by suggesting that the discontinuity is indeed driven by families who were restricted in access before, but were allowed to claim a place in publicly funded childcare after crossing the threshold.

Fig. 1.

The figure shows the share of children attending childcare at the time of the interview by age of the child (in months) at the time of the last childcare start. The dots mark averages over bins of 3 months. The lines show a quadratic fit to the original data on either side of the cut-off.

Source: SOEP v31, own calculation

The estimation results of the first stage (Eq. 1) in Table 2 confirm the simple graphical evidence. There is a significant jump in childcare attendance of 16.7 percentage points.15 The robust F-test statistic (319.09) is well above the usual rule-of thumb value, indicating that the cut-off rule is indeed a strong predictor of childcare attendance. Including the additional set of individual covariates (see Table 1) and a set of (separate) season and year dummies does not change the estimated discontinuity. Note, that all specifications include individual fixed effects as well as a piecewise linear and quadratic age trend. To support the “supply side-restriction story,” I estimate the first stage separately in East and West Germany. Since childcare rationing was primarily an issue in West Germany, it is not surprising to see that the discontinuity is actually much larger in West than in East Germany (Columns 3 and 4 in Table 2). In line with this argument, districts with lower childcare coverage should also exhibit a larger share of families who act in compliance with the cut-off rules. Linking the SOEP households to administrative records on childcare provision at the district level (Statistisches Bundesamt 2004), I find that the first stage is indeed more than two times larger in districts with below median childcare coverage than in districts with above median childcare coverage.16 Furthermore, the cut-off rules were more frequently applied during the early periods when supply side shortages were more severe (BMFSFJ 2005). This is only partly reflected in the estimated coefficients in columns 7 and 8. Families with children born between 1992 and 1995 are somewhat more likely to act in compliance with the cut-off rules than families with children born between 1996 and 2000. However, the coefficients are not significantly different from each other. Graphical evidence on the first-stage heterogeneities is provided in Figure A3 in Online Appendix.

Table 2.

First-stage results

| Childcare attendance at the time of the interview | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Full sample | Full sample | West Germany | East Germany | Low coverage | High coverage | Child born 1992–1995 | Child born 1995–2000 | |

| Above cut-off age | 0.167*** | 0.168*** | 0.212*** | 0.018 | 0.241*** | 0.110*** | 0.172*** | 0.149*** |

| (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.029) | (0.042) | (0.039) | (0.034) | (0.030) | (0.046) | |

| Controls | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nbr. observations | 7897 | 7897 | 6343 | 1554 | 3432 | 3432 | 5134 | 2763 |

| Nbr. mother/child pairs | 1743 | 1743 | 1412 | 358 | 936 | 932 | 1155 | 588 |

| R-squared | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 0.64 |

The table displays the first-stage RD estimates. All models include a piecewise linear and quadratic age trend and individual fixed effects. Columns 2–7 include a set of (separate) season and year dummies and the additional covariates on the individual level displayed in Table 1. In columns 3 and 4, the first stage is estimated separately for West and East Germany. Columns 5 and 6 estimate the first stage separately for districts with above and below median childcare coverage. Data on childcare use at the district level (Statistisches Bundesamt 2004) are merged via district identifiers to SOEP households. The sample for columns 7 and 8 consists of mothers with children born between 1992–1995 and 1996–2000, respectively. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. * 10% level of significance, ** 5% level of significance, *** 1% level of significance

Source: SOEP v31, own calculation

Investigating the first stage for different subgroups shows that higher educated mothers, older mothers, parents with more than one child, as well as cohabiting and married mothers respond more strongly to the cut-off rules (Table A2 in Online Appendix). Hence, the complier population primarily consists of parents with higher socio-economic status. For example, single parents were hardly affected by the cut-off rules, which is in line with (informal) regulations in childcare centres, according to which single parents are preferred in access and frequently can jump waiting lists (Fuchs and Peucker 2006).

The Effect on Parental Subjective Well-Being

Table 3 reports the ITT and LATE estimates for the maternal subjective well-being variable. For completeness, it also depicts the first-stage regression coefficients. The reduced form result in column 2 provides the ITT effect, i.e. it estimates the effect of being eligible to a place in publicly funded childcare by the cut-off criteria independent of the actual take-up. The coefficient is obtained by regressing the discontinuity in the assignment variable directly on the outcome. The reduced form coefficients show that being eligible for publicly funded childcare increases maternal life satisfaction by an average of 0.088 points on the 11-point Likert scale, which corresponds to an increase of about 0.06 standard deviations. Figure A4 is a graphical representation of the reduced form; again, dots indicate monthly averages.

Table 3.

The impact on maternal life satisfaction—fuzzy RD estimates

| Maternal life satisfaction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Without controls | With controls | |||||

| 1st stage | Reduced form | 2nd stage | 1st stage | Reduced form | 2nd stage | |

| Above cut-off age | 0.167*** | 0.088** | 0.168*** | 0.087** | ||

| (0.025) | (0.040) | (0.025) | (0.039) | |||

| Childcare attendance | 0.528** | 0.518** | ||||

| (0.222) | (0.220) | |||||

| Controls | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nbr. observations | 7897 | 7897 | 7897 | 7897 | 7897 | 7897 |

| Nbr. mother–child pairs | 1743 | 1743 | 1743 | 1743 | 1743 | 1743 |

| R-squared | 0.64 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

The table displays the first-stage, reduced form and second-stage RD coefficients. All models include a piecewise linear and quadratic age trend and individual fixed effects. Columns 3–5 include the additional set of covariates on the individual level displayed in Table 1 and season and year dummies. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. *10% level of significance, ** 5% level of significance, *** 1% level of significance

Source: SOEP v31, own calculation

The second-stage estimates from Eq. (2) are depicted in column 3 of Table 3. The estimated LATE suggests that publicly funded childcare significantly increases maternal life satisfaction by 0.528 points on the 11-point Likert scale for the group of compliers. As shown in columns 3–5, all estimated coefficients are robust to the inclusion of the various control variables on the individual level described in section 2.2 and the set of (separate) season and year dummies. In line with the adaptation theory (Clark et al. 2008; Kahneman and Krueger 2006), the effects on maternal life satisfaction fade out over time (see Figure A4).17 Comparing the magnitude of the estimated increase in maternal life satisfaction with recent findings in the well-being literature suggests that childcare provision, i.e. the abandoning of supply side restriction on the childcare market, amounts, for example, to half the size of entry into unemployment due to plant closure for West German women (Kassenboehmer and Haisken-DeNew 2009).

Table 4 and the right-hand side panel of Figure A4 show the same results for paternal life satisfaction. Neither the LATE nor the ITT is significantly different from zero. However, the estimated coefficients are large and the magnitude is about 40% of the coefficient for maternal life satisfaction. The first stage is a bit stronger, reflecting that cohabiting parents comply more readily with the cut-off rules (see Sect. 5.1). Note that control variables in columns 3–5 also include paternal labour market outcomes—employment status, working hours, and log labour income—that are not affected by the treatment. These explain a lot of the variation in the dependent variable, resulting in more efficient estimates.

Table 4.

The impact on paternal life satisfaction—fuzzy RD estimates

| Paternal life satisfaction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Without controls | With controls | |||||

| 1st stage | Reduced form | 2nd stage | 1st stage | Reduced form | 2nd stage | |

| Above cut-off age | 0.171*** | 0.038 | 0.173*** | 0.039 | ||

| (0.027) | (0.043) | (0.027) | (0.041) | |||

| Childcare attendance | 0.221 | 0.223 | ||||

| (0.218) | (0.216) | |||||

| Controls | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nbr. observations | 6833 | 6833 | 6833 | 6833 | 6833 | 6833 |

| Nbr. mother–child pairs | 1593 | 1593 | 1593 | 1593 | 1593 | 1593 |

| R-squared | 0.63 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.64 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

The table displays the first-stage, reduced form and second-stage RD coefficients. All models include a piecewise linear and quadratic age trend and individual fixed effects. Columns 3–5 include the additional set of covariates on the individual level displayed in Table A1 and season and year dummies. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. *10% level of significance, ** 5% level of significance, *** 1% level of significance

Source: SOEP v31, own calculation

In the following, I assess whether the effects on maternal life satisfaction differ with respect to the following factors: mother’s intention to work, years of schooling, and migration background. Therefore, I split the data accordingly and re-estimate the model in the respective sub-samples. Results in Table A3 show that the effect is more pronounced for mothers who state that they intend to engage in paid employment (again) in the future when the child was one year old. Furthermore, the effect is more pronounced for mothers with more years of schooling (in the second and third quantile of the education distribution) and mothers with no migration background. I refer to this group as mothers with a stronger labour market attachment. In line with this finding, the labour market outcomes in Table 5 are more pronounced for this group, indicating that mothers with a weaker labour market attachment prefer to stay at home with their children anyway and/or face stronger re-entry restrictions.18 Note, however, that due to sample size limitations it is not possible to detect significant differences between the estimated coefficients for all subgroups.

Table 5.

Potential mechanisms—fuzzy RD estimates

| Panel A—income and employment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Log gross labour income | Log net hh labour income | Part-time employment | Marginal employment | Full-time employment | |

| Childcare attendance | 1.470*** | 0.070* | 0.189*** | − 0.032 | 0.057 |

| (0.422) | (0.043) | (0.060) | (0.044) | (0.041) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nbr. observations | 7881 | 7537 | 7898 | 7898 | 7898 |

| Nbr. mother/child pairs | 1742 | 1697 | 1743 | 1743 | 1743 |

| R-squared | 0.26 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Panel B—time use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Childcare | Labour market | Housework | Errands | Leisure | |

| Childcare attendance | − 1.260** | 1.408*** | − 0.643** | − 0.125 | − 0.444** |

| (0.508) | (0.432) | (0.262) | (0.121) | (0.198) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nbr. observations | 7887 | 7785 | 7791 | 7769 | 7582 |

| Nbr. mother/child pairs | 1742 | 1733 | 1735 | 1728 | 1713 |

| R-squared | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

The table displays second-stage RD estimates. All models include a piecewise linear and quadratic age trend, individual fixed effects, season and year dummies and the additional set of covariates on the individual level displayed in Table 1. Time use is measured in hours and refers to a typical work day. Robust standard errors in parenthesis. * 10% level of significance, ** 5% level of significance, *** 1% level of significance

Source: SOEP v31, own calculation

Mechanisms

Childcare attendance changes several aspects of daily life that could potentially contribute to the observed effect on maternal life satisfaction. In the following, the theoretical and empirical discussion focuses on two: labour market outcomes and time use.19

More specifically, public childcare provision in Germany is shown by Bauernschuster and Schlotter (2015) to strongly increase maternal labour supply at the extensive and intensive margins, providing potential direct or indirect pecuniary and non-pecuniary returns to maternal life satisfaction. Pecuniary returns result from changes in labour market earnings, which are well known to positively impact subjective well-being (e.g. Easterlin 1973). Gains in earnings are likely to be larger for women who do not enter in marginal employment but rather find regular full- or part-time positions. Maternal employment also changes the share of household income provided by the mother. As predicted by collective household models (see Chiappori 1988, for the basic theory), this increases maternal bargaining power over household consumption patterns, which is shown by several studies to result in a larger share of the household budget being used for goods related to children’s and family’s well-being (e.g. Haeck et al. 2014). Since childcare fees are very low in Germany and many low-income families are exempt from paying fees (OECD 2006; Schmitz et al. 2017), there is hardly any direct, mitigating, effect of childcare fees on disposable income—even in the absence of any employment effects.

Non-pecuniary returns from mother’s participation in the workforce might evolve because employment brings with it prestige, enhancing social connection and interaction with colleagues, which is shown to be positively associated with subjective well-being (e.g. Helliwell and Putnam 2005) and is rated highly by individuals on momentary well-being scales (Bryson and MacKerron 2017). Furthermore, the failure to meet employment aspirations, i.e. an incongruence between a mother’s desired and actual employment status, is shown by Berger (2013) and Klein et al. (1998) to be associated with a reduction in maternal subjective well-being or an increase in depressive symptoms. Thus, if the availability of formal childcare allows mothers to (better) combine family and career (e.g. by allowing to choose the preferred working hours), one would expect a strong increase in maternal well-being.20 As discussed in several papers by Booth and Van Ours (2008); Booth and Van Ours (2013), women often report the highest well-being when working part-time. Maternal employment could, on the other hand, also have detrimental non-pecuniary effects, in particular if mothers re-enter in low wage or marginal occupations that have low social recognition and are rated with low satisfaction levels (Kahneman et al. 200a).21 In addition, mothers might struggle with the double burden imposed by a second-shift of unpaid housework and childrearing (Hochshild 1989). This is the main explanation of previous studies finding that childcare subsidies actually have an adverse effect on maternal well-being (see also Connolly and Haeck 2015, for a survey). If this explanation is true in the German setting, one would see that formal childcare crowds out leisure, but has no effect on time spent doing housework and childcare.

Even in the absence of changes in maternal labour market outcomes, formal childcare might have non-pecuniary returns to life satisfaction by changing the amount and quality of time devoted to different non-market activities. For example, formal childcare provides a valuable platform to enhance social connections and interaction with parents of other children. Using a day reconstruction method, Kahneman et al. (2004b) demonstrates that socializing is rated by women to be an enjoyable activity, while "taking care of one’s children" ranks just above the least enjoyable activities of "working, housework, and commuting". Similar conclusions are drawn by Bryson and MacKerron (2017) using an experience sampling method. Hence, one would expect an increase in well-being if childcare provision allows parents to shift time from less to more enjoyable activities.22

Table 5 provides empirical evidence on the mechanisms.23 Graphical evidence is provided in Figure A5 and Figure A6 in Online Appendix. Concerning maternal labour market outcomes, results in panel A of Table 5 show that mothers are 18.9 percentage points more likely to regularly work in a part-time job. However, there is no significant effect on the probability to work in marginal or full-time employment. Note that the fraction of mothers holding a permanent job contract is higher in regular part-time jobs (75%) than in full-time (71%) or marginal jobs (55%). Overall, adding up the mutually exclusive employment categories, the impact on maternal employment amounts to an increase in the probability to work of about 22 percentage points which is very similar to the coefficient obtained by Bauernschuster and Schlotter (2015). Consequently, maternal gross labour income increases strongly by an average of 147%. However, household net labour income is affected to a much lower extent, reflecting the splitting income taxation between married couples in Germany. As discussed in detail above, it seems likely that this increase in permanent part-time employment and earnings result in large direct or indirect pecuniary and non-pecuniary returns to maternal life satisfaction.

Concerning time use, I find that publicly funded childcare decreases time spent with children by an average of 1.3 h per day (column 1 in Panel B). Since the right to a legal claim covers half-day childcare (roughly 4 h per day), one would expect an increase by at least 4 h. However, as mentioned in Sect. 3, the question in the SOEP is not precisely stated and answers indicate that respondents do not interpret the question in the same way: i.e. there is some bunching at 12 and 24 h indicating that some mothers think of 12 and 24 h per day as the maximum amount of childcare.24 Of course, it could also be that mothers interact with their children more frequently in the afternoon than they would have if the child did not attend childcare, i.e. reflecting a compensating behaviour. Furthermore, column 2 of Table 5 shows that childcare attendance increases maternal time spent on the job or training strongly by about 1.4 h per day. It is also evident that childcare decreases maternal housework by an average of 0.6 h per day (column 3), does not alter the time spent on running errands (column 4), but diminishes leisure by 0.4 h per day (column 5). Taken together, the results suggest that mothers shift time from non-market activities—including leisure, housework, and time spent with children—to formal work in response to childcare eligibility.

Table A4 in Online Appendix shows that all coefficients on paternal labour market outcomes are not significant and very close to zero, i.e. fathers do not seem to compensate their partners for their shift from non-market activities to formal work. This might reflect the rigid gender roles in Germany and is consistent with men showing a higher attachment to the labour force than women and a lower elasticity of labour supply. The estimated coefficients on time use of fathers are also not significantly different from zero. However, the null-effects are imprecisely estimated.

Robustness

The fuzzy RDD requires three assumptions to yield internally valid estimates. First, the conditional expectations of the potential outcomes must be smooth functions, i.e. all other factors should evolve continuously with respect to the assignment variable and there should be no other discontinuities along the distribution of the assignment variable. Second, the assignment mechanism must be well known to the researcher but individuals must not be able to manipulate it with precision. The latter is fulfilled by definition since individuals cannot manipulate their child’s age. However, they could time the date of birth—an argument put forth by Buckles and Hungerman (2013) in the debate on using quarter of birth instruments. Third, there should be a discontinuity in the probability of treatment at the cut-off, i.e. compliance with the cut-off without violation of the monotonicity assumption. These assumptions are carefully assessed in the following.

Concerning the first and second assumptions, I test for discontinuities in other factors that should evolve continuously around the cut-off. More specifically, I test whether the age of the mother, years of education, marital and cohabitation status, the number of siblings, or partner’s log income exhibit a jump at the 36-month cut-off. The second-stage coefficients are depicted in Table A5. All coefficients are very close to zero and not statistically significant.

Furthermore, I estimate several placebo regressions, which are reported in Table A6. In particular, I carefully assess whether direct age effects confound the analysis, i.e. one concern for example is that mothers report higher life satisfaction because their children are older and easier to look after regardless of child care attendance. Columns 1 and 2 present the first-stage and the reduced form regression estimates in a period before the legal claim to publicly funded childcare was implemented, i.e. for mothers with children born between 1986 and 1991. Hence, column 1 tests the relevance of the cut-off rules in periods where no cut-off rules should exist. As expected, the first-stage coefficient is close to zero and not statistically significant. The reduced form in column 2 is also close to zero and not statistically significant. Under the assumption that any direct age effects are constant across years, this supports the assumption that the main results are not driven by direct age effects but are indeed induced by the discontinuity in childcare attendance at the cut-off. Also note that if direct age effects confounded the analysis, they would have to be discontinuous at the cut-off. Next, I test for a jump at a non-discontinuous point as suggested by Imbens and Lemieux (2008). Therefore, I split the sample at the cut-off into two sub-samples. Then, I estimate the first stage and the reduced form using the median of the left-hand side sub-sample as a placebo cut-off. Coefficients of this placebo exercise are depicted in columns 3 and 4. They are not statistically significant, which further strengthens the validity of the empirical strategy.

In addition, I investigate the sensitivity of the results with respect to the chosen bandwidth and polynomials. I estimate the main model using different bandwidths around the threshold. Figure A7 plots the estimated coefficients against the chosen bandwidths, i.e. when using the full sample, 85%, and 70% of the baseline sample. Note that all outcomes have been standardized to depict them on a common scale. It is evident that coefficients are quite stable across the different bandwidth specifications. However, as expected, the precision of the estimated second-stage coefficients decreases as I restrict the bandwidth closer to the cut-off due to the lower number of observations. Concerning the polynomial order, in Table A7 it is evident that choosing a linear specification of the direct age effects results in smaller second-stage RD coefficients while higher polynomials tend to increase the coefficient on maternal well-being. Note that according to the AIC and the BIC, the preferred model overall is the one with a second-order polynomial of the assignment variable. Figure A8 depicts the results from the same exercise for paternal well-being as well as all the mechanisms (maternal labour market outcomes and time use) which were examined in Sect. 5.3.

As an additional robustness check, I make the subjective well-being variable binary by splitting it by its median. Results are reported in Table A8 in Online Appendix. The coefficient remains highly significant and corresponds to an increase in the probability to report above median well-being by about 17 percentage points, which corresponds to 33% of a standard deviation, i.e. an effect size that is very similar to the main specification. Furthermore, I include the characteristics of the partner for cohabiting mothers and mother’s own health status (two separate regressions). Partner’s education, earnings and the own health status are very strong predictors of maternal subjective well-being, but the inclusion does not change the estimated coefficients. As a final robustness check, I estimate the regression in a sample without attrition, i.e. for the sub-samples of mothers who can be observed in all survey years where the child is between zero and six years old. Coefficients are very similar to the ones in the main specification.25

Conclusion

As more and more countries consider expanding public childcare provision, it is important to have a comprehensive understanding of its implications for both parental and child well-being. This contribution investigates the impact of publicly funded childcare on parental subjective well-being in Germany. To establish causality, I use a fuzzy Regression Discontinuity Design to exploit a discontinuity in childcare attendance caused by cut-off rules. These cut-off rules were introduced after the implementation of a legal claim to childcare for all children from age three until school entry in 1996. The analysis is based on SOEP data, using the well-established life satisfaction measure as the main outcome.

The results indicate that access to and attending publicly funded childcare significantly increase the subjective well-being of mothers who were previously constrained by the lack of childcare supply, while fathers are less affected. To investigate potential mechanisms behind this increase, a wide range of time-use and labour market outcomes are explored. The results show that mothers indeed shift time from non-market activities—including housework and time spent with children—to formal work in response to childcare eligibility, resulting in potentially large direct or indirect pecuniary and non-pecuniary returns to maternal life satisfaction. The positive impact on life satisfaction is more pronounced for mothers with a strong labour market attachment, i.e. mothers who state that they intend to engage in paid employment (again) in the future when the child was one year old, mothers with higher education and no migration background. This suggests that expanding public childcare provision can reduce the incongruence between actual and desired employment of mothers, thus increasing their life satisfaction.

It is important to note that this paper identifies short-run effects. It is beyond the scope of this paper to address any long-run or general equilibrium effects. In addition, the estimation strategy identifies a local average treatment effect, i.e. the effect for the complier population. Compliers are families who faced severe supply side restrictions on the childcare market before the implementation of the legal claim to childcare, but claim a childcare place once the child becomes eligible by the cut-off rules. This effect does not necessarily generalize to other government interventions aimed at increasing childcare attendance, e.g. employment-based programs, universal or targeted subsidy programs. In contrast to previous analysis of the impact of childcare reforms on parental subjective well-being in the USA and Canada, the analysed childcare reform in Germany covers only half-day childcare and the institutional setting and cultural beliefs in Germany promote part-time work more readily. Furthermore, the population under study consists mainly of parents with a higher socio-economic background since those parents comply with the cut-off rules. This is in contrast to the evaluation of subsidy programs which target disadvantaged families or other subsidy programs that aim to increase childcare attendance by lowering childcare fees. Hence, differences between the findings in this article and other quasi-experimental evidence reflect the different institutional settings and government interventions that are exploited for identification.

Taken together, what we can learn from the previous literature and the results in this article is that abandoning childcare rationing in general will have beneficial effects on mothers’ subjective well-being. However, if public childcare provision induces mothers to work full-time on the labour market and then complete a second-shift of unpaid housework and childrearing, reconciliation issues might evolve that make mothers feel more stressed, depressed, and less satisfied with their life. Research on how family policies can lower the double burden, e.g. by promoting a more equal division of labour, should be pursued.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to participants of the ESPE conference 2017, the VfS Annual Conference 2017 and EALE conference 2017. I am also grateful to C. Katharina Spieß, Vaishali Zambre, Aline Zucco and Adam Lederer for helpful comments and suggestions. All errors are my own.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Some even argue that subjective well-being measures are the best available proxy to utility—a concept central to economic research (see Frey and Stutzer 2002, for a survey).

Besides being a crucial indicator for how parents think and feel about their lives, parental subjective well-being also constitutes an important mechanism through which child well-being and development is affected (Berger and Spiess 2011; Minkovitz et al. 2005), in particular by influencing the quality and quantity of parental investment within the home environment as well as family formation and stability (Guven et al. 2012; Aassve et al. 2016; Luppi 2016). Thus, when examining the impact of public childcare on child development, it is crucial to take into account parental well-being as a potential pathway.

Note that all well-being effects identified in this paper are short-run effects. There is an ongoing debate in the well-being literature whether policies can change well-being in the long run (e.g. Diener et al. 2009; Kőszegi and Rabin 2008; Dolan and White 2007). However, it is beyond the scope of this paper to address any long-run or general equilibrium effects.

Bauernschuster and Schlotter (2015) and Schlotter (2011) were the first to exploit these cut-off rules as a source of exogenous variation in childcare attendance to study labour supply responses and the impact of childcare on child development.

There is also a small literature on the impact of informal care arrangements on the well-being of the extended family, e.g. Brunello and Rocco (2018) show that informal childcare has detrimental effects on grandmothers’ and grandfathers’ mental well-being in Europe.

One interpretation of the authors for the negative findings is the so-called second-shift effect (Hochshild 1989), which means that mothers are induced to enter the labour market in full-time employment but still bear the brunt of housework and childrearing after formal care ends. The extent to which mothers struggle with this double burden and the extent to which the increased amount of disposable income benefits the well-being of parents depend on their characteristics.

One reason why no private market ever emerged—despite the supply side shortages and severe childcare rationing—is the strict regulatory requirements set by the government of the federal states, including strict hygiene and health standards as well as strict requirements regarding the premises, quantity, and quality of personal (see Bildungsserver 2017).

In Germany, administration, organization and legislation of culture—including education and care—fall within the competences of the federal states. This means that every federal state has to draft and finance its own laws and regulations for early childhood education and care, school education, and the university system.

By 2005, public expenses on childcare amounted to more than 11 billion Euro, most of it spent on operational expenses. This number is more than doubled than that spent in 1991 (Statistisches Bundesamt 2014).

I refer to the father as the current partner of the mother who is living in the same household. It does not necessarily have to be the biological father of the child.

In principal, life satisfaction is a latent variable that cannot be observed directly, which makes it common to ask survey respondents to grade their life satisfaction on an ordinal scale (Schroeder and Yitzhaki 2017). Assuming cardinality of this ordinal variable imposes several assumptions, e.g. all respondents interpret the question in a similar way, the distance between items in terms of the latent underlying variable is equal.

Most children stay in formal childcare once they start attending it, i.e. dropping out of formal childcare or longer absent periods are very rare in Germany (Büchner and Spiess 2007).

Note that time-invariant characteristics, such as migration background, education, gender of the child or potential disorders, are automatically controlled for by including individual fixed effects.

One concern with the variable is that the question is not clearly stated. There is some bunching at 12 and 24 h, indicating that some parents consider 24 h as the maximum, while others consider 12 h of childcare per day the maximum. This has to be kept in mind when interpreting the results. However, I conduct several sensitivity estimations, all yielding qualitatively and quantitatively similar results.

Note that the estimated coefficients are remarkably similar to those obtained by Bauernschuster and Schlotter (2015) and Schlotter (2011), even though a different model and sample is used.

The administrative data on childcare attendance rates were collected in 4-year intervals, i.e. in 1994, 1998 and 2002. I imputed the missing data by assuming a linear growth in childcare attendance rates. Slightly changing the imputation method does not change the estimated coefficients. The years after 2002 are dropped from the analysis since the categories collected in the administrative data were changed and, thus, are not comparable to previous years.

The adaptation theory says that that individuals habituate to life circumstances very quickly (“hedonic treadmill”) or adjust their well-being aspiration to the utility that they experience (“aspiration treadmill”). Thus, people adjust to major life events (almost), fully returning to the initial baseline level of well-being.

These additional results can be obtained from the author upon request.

Another potentially important mechanism is child development. Under the assumption that parents have an altruistic utility function, i.e. they derive utility from the development of their children, childcare attendance could have either detrimental or beneficial effects on the well-being of parents, depending on how children are affected by being cared for in formal childcare. Indeed, information from the Families in Germany (FiD) data set shows that, during 2010–2013, child development is the most important reason (stated by 64% of parents with 3-year-old children in formal childcare) for parents to send their child to formal childcare, followed by employment related reasons (stated by 15%) and leisure time arguments (stated by 8%). In addition, it might be important how parents feel about sending their child to formal childcare; i.e. the pure perception of whether they think that childcare will harm or benefit their child might have an additional effect on their subjective well-being. One important factor in that respect is childcare quality. The same logic applies to social norms or pressure; i.e. in Germany maternal care during childhood was long thought as ideal, deviating from it might induce maternal guilt, thus decreasing their well-being. However, due to data restrictions it is not possible to take into account child development or norms as a potential pathway.

This might be particularly important in Germany since women have high educational attainment despite their low labour force participation and, thus, might wish to achieve their full labour market potential.

Occupational change is another potential mechanism. However, in Germany, in general, and in this study’s specific sample, changing occupation is rare (less than 10% of mothers report an occupational change).

Unfortunately, information on different free-time activities (e.g. civic engagement, exercising, meeting with friends) is only available for a few years in the SOEP data. Thus, I can only consider the amount of free-time, rather than provide a more differentiated analysis by taking into account the specific type of free-time activity.

For completeness, I conducted a standard mediation analysis. As expected, including time use, income, and employment as explanatory variables in the regression decreases the coefficient on childcare attendance and makes it insignificant.

However, the results are not sensitive to alternative specifications, e.g. assuming that the maximum amount of childcare is 24 h, suggesting that the individual fixed effects already control for most of the systematic measurement error. Standardizing time use for each individual by taking the fraction of time spent on the respective activity relative to the maximum amount of time stated also does not change the conclusion.

These additional robustness checks can be obtained from the author upon request.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aassve A, Arpino B, Balbo N. It takes two to tango: Couples’ happiness and childbearing. European Journal of Population. 2016;32(3):339–354. doi: 10.1007/s10680-016-9385-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M, Gruber J, Milligan K. Universal child care, maternal labor supply, and family well-being. Journal of Political Economy. 2008;116(4):709–745. [Google Scholar]

- Bauernschuster S, Schlotter M. Public child care and mothers’ labor supply—Evidence from two quasi-experiments. Journal of Public Economics. 2015;123:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Berger EM. Happy working mothers? Investigating the effect of maternal employment on life satisfaction. Economica. 2013;80(317):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Berger EM, Spiess CK. Maternal life satisfaction and child outcomes: Are they related? Journal of Economic Psychology. 2011;32(1):142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, M. (2011). Chapter 17—New perspectives on gender. In D. Card & O. Ashenfelter (Eds.), Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 4, pp. 1543–1590). Elsevier.

- Bertrand M. Career, family, and the well-being of college-educated women. The American Economic Review. 2013;103(3):244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Bildungsserver. (2017). Ausführungsgesetze der Länder zu Tageseinrichtungen für Kinder.

- BMFSFJ. (2005). Zwölfter Kinder- und Jugendbericht—Bericht über Lebenssituation junger Menschen und die Leistungen der Kinder- und Jugendhilfe in Deutschland. Berlin.

- BMFSFJ. (2012). Ausgeübte Erwerbstätigkeit von Müttern – Erwerbstätigkeit, Erwerbsumfang und Erwerbsvolumen 2010. Berlin.

- Booth AL, Van Ours JC. Job satisfaction and family happiness: The part-time work puzzle. The Economic Journal. 2008;118(526):F77–F99. [Google Scholar]

- Booth AL, Van Ours JC. Part-time jobs: What women want? Journal of Population Economics. 2013;26(1):263–283. [Google Scholar]

- Brodeur A, Connolly M. Do higher child care subsidies improve parental well-being? Evidence from quebec’s family policies. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 2013;93:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Brunello G, Rocco L. Grandparents in the blues. The effect of childcare on grandparents’ depression. Review of economics of the household. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Bryson A, MacKerron G. Are you happy while you work? The Economic Journal. 2017;127(599):106–125. [Google Scholar]

- Büchner, C. & Spiess, C. K. (2007). Die Dauer vorschulischer Betreuungs-und Bildungserfahrungen: Ergebnisse auf der Basis von Paneldaten.

- Buckles KS, Hungerman DM. Season of birth and later outcomes: Old questions, new answers. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2013;95(3):711–724. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappori PA. Rational household labor supply. Econometrica. 1988;56(1):63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Clark AE, Diener E, Georgellis Y, Lucas RE. Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis. The Economic Journal. 2008;118(529):222–243. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly M, Haeck C. Are childcare subsidies good for parental well-being? Empirical evidence from three countries. CESifo DICE Report. 2015;13(1):09–15. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Lucas RE, Scollon CN. Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. In: Diener E, editor. The science of well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener. Dordrecht: Springer; 2009. pp. 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan P, Peasgood T, White M. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology. 2008;29(1):94–122. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan P, White MP. How can measures of subjective well-being be used to inform public policy? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2(1):71–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Magnuson K. Investing in preschool programs. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2013;27(2):109–132. doi: 10.1257/jep.27.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RA. Does money buy happiness? The Public Interest. 1973;30:3. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbinghaus H. Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. New York: Dover; 1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . The provision of childcare services—A comparative review of 30 European countries. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-i Carbonell A, Frijters P. How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal. 2004;114(497):641–659. [Google Scholar]

- Frey BS, Stutzer A. What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature. 2002;40(2):402–435. [Google Scholar]

- Frijters P, Haisken-DeNew JP, Shields MA. Investigating the patterns and determinants of life satisfaction in Germany following reunification. Journal of Human Resources. 2004;39(3):649–674. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, K., & Peucker, C. (2006). “ ... und raus bist du!” Welche Kinder besuchen nicht den Kindergarten und warum. In Bien, Walter, T. R. & Riedel, B. (Eds.), Wer betreut Deutschlands Kinder? DJI-Kinderbetreuungstudie (pp. 61–81). Beltz Juventa.

- Garces E, Thomas D, Currie J. Longer-term effects of Head Start. The American Economic Review. 2002;92(4):999–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Glass J, Simon RW, Andersson MA. Parenthood and happiness: Effects of work-family reconciliation policies in 22 OECD countries. American Journal of Sociology. 2016;122(3):886–929. doi: 10.1086/688892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guven C, Senik C, Stichnoth H. You can’t be happier than your wife Happiness gaps and divorce. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 2012;82(1):110–130. [Google Scholar]

- Haeck, C., Lefebvre, P. & Merrigan, P. (2014). The power of the purse: New evidence on the distribution of income and expenditures within the family from a Canadian experiment. Cahier de recherche/Working Paper (Vol. 14, p. 15).

- Helliwell JF, Putnam RD. The social context of well-being. In: Huppert FA, Baylis N, Keverne B, editors. The science of well-being. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst CM, Tekin E. Child care subsidies, maternal health, and child-parent interactions: Evidence from three nationally representative datasets. Health Economics. 2014;23(8):894–916. doi: 10.1002/hec.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochshild A. The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York: Penguin Books; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Imbens GW, Lemieux T. Regression discontinuity designs: A guide to practice. Journal of Econometrics. 2008;142(2):615–635. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Krueger AB. Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20(1):3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Krueger AB, Schkade D, Schwarz N, Stone A. Toward national well-being accounts. The American Economic Review. 2004;94(2):429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Krueger AB, Schkade DA, Schwarz N, Stone AA. A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science. 2004;306(5702):1776–1780. doi: 10.1126/science.1103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassenboehmer SC, Haisken-DeNew JP. You’re fired! The causal negative effect of entry unemployment on life satisfaction. The Economic Journal. 2009;119(536):448–462. [Google Scholar]

- Klein MH, Hyde JS, Essex MJ, Clark R. Maternity leave, role quality, work involvement, and mental health one year after delivery. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1998;22(2):239–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kőszegi B, Rabin M. Choices, situations, and happiness. Journal of Public Economics. 2008;92(8):1821–1832. [Google Scholar]

- Kottelenberg MJ, Lehrer SF. New evidence on the impacts of access to and attending universal child-care in Canada. Canadian Public Policy. 2013;39(2):263–286. [Google Scholar]

- Kultusminister Konferenz. (2016). Archiv der Ferienregelungen.

- Luppi F. When is the second one coming? The effect of couple’s subjective well-being following the onset of parenthood. European Journal of Population. 2016;32(3):421–444. doi: 10.1007/s10680-016-9388-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Scharfstein D, Hou W, Miller T, Mistry KB, Swartz K. Maternal depressive symptoms and children’s receipt of health care in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2):306–314. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . Society at a glance 2006–OECD Social Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- OECD . Doing better for families. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- OECD . How’s life? 2015: Measuring well-being. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]