Abstract

Leaf senescence is an important developmental process for the plant life cycle. It is controlled by endogenous and environmental factors and can be positively or negatively affected by plant growth regulators. It is characterised by major and significant changes in the patterns of gene expression. Auxin, especially indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), is a plant growth hormone that affects plant growth and development. The effect of IAA on leaf senescence is still unclear. In this study, we performed microarray analysis to investigate the role of IAA on gene expression during senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. We sprayed IAA on plants at 3 different time points (27, 31 or 35 days after sowing). Following spraying, PSII activity of the eighth leaf was evaluated daily by measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. Our results show that PSII activity decreased following IAA application and the IAA treatment triggered different gene expression responses in leaves of different ages.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12298-019-00752-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, IAA, Gene expression, Microarray, PSII activity, Leaf senescence

Introduction

Leaf senescence is a plastic process governed by various factors which may be endogenous or exogenous, such as the developmental stage of the plant, leaf age, levels of different phytohormone, darkness, and exposure to various stresses (Buchanan-Wollaston et al. 2003; Sharabi-Schwager et al. 2010; Yamada et al. 2014). Senescence occurs in an orderly progression, beginning with the degeneration of the chloroplast followed by hydrolysis and remobilisation of macromolecules (Lim et al. 2007; Gregersen et al. 2013; Ueda and Kusaba 2015). The intial symptoms of senescence are a photosynthetic rate decline and an increase in the rate of respiration. Other changes include breakdown of chloroplast membranes, loss of chlorophyll, and breakdown of proteins and lipids (Lim et al. 2007). A decrease of PSII activity has been shown to occur during the senescence (Fan et al. 1997; Lu et al. 2001; Breeze et al. 2008), as a consequence of photosystem damage (Barbagallo et al. 2003). Chloroplasts are rich reservoirs of proteins such as Rubisco, chlorophyll a/b-binding proteins, as well as membrane lipids. Chloroplasts are degraded first, while the mitochondria and peroxisomes initially remain functional. Nuclei also remain functional and transcriptionally active, although early ribosomal degradation occurs and total RNA levels decrease (Srivastava 2002; Balazadeh 2014).

Hormones are endogenous components that mediate the effect of developmental and environmental factors to regulate senescence, among other physiological processes. Some hormones such as ethylene, abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid (JA), and salicylic acid (SA) act as inducers of senescence, whereas cytokinins and gibberellins play an important role in its suppression (Morris et al. 2000; He et al. 2002; Lim and Nam 2007; Jibran et al. 2013; Yamada and Umehara 2015). Auxin, especially indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), is a plant growth hormone that affects plant growth and development (Zhao 2010; Jusoh et al. 2015). IAA mediates a number of essential processes, such as cell elongation, induction of root growth, and flower and fruit development (Bashri and Prasad 2016). In addition, auxin plays important roles in the suppression of the leaf senescence (Jiang et al. 2014; Shi et al. 2015). Synthetic and natural auxins have been reported to delay senescence in certain plant tissues. (Chamarro et al. 2001; Sarwat et al. 2013). However, Gören and Çag (2007) showed that senescence in the cotyledons of Helianthus annuus L. seedlings was accelerated by the application of IAA.

Leaf senescence is an important stage in leaf development and involves the altered expression of a large number of senescence-associated genes (SAGs). In recent years, microarray analysis on leaf senescence studies has facilitated the identification and isolation of thousands of genes whose expression is induced in senescent leaves (Buchanan-Wollaston et al. 2005; van der Graaff et al. 2006; Breeze et al. 2008, 2011; Hickman et al. 2013). While the expression of SAGs is promoted during senescence, the expression of genes such as photosynthesis-associated genes is suppressed (De Michele et al. 2009). Various SAGs show a different expressions pattern in different tissues and respond differently to senescence-promoting factors such as hormones, SA, ozone, UV radiation, darkness (Farage-Barhom et al. 2008). During senescence, intense catabolic processes occur, resulting in macromolecule degradation (Fischer 2007), and some of the SAGs encode hydrolytic enzymes such as proteases and nucleases (Buchanan-Wollaston et al. 2005). Studies at the molecular level have shown that SA, JA and ethylene promote the expression of genes encoding transcription factors that regulate SAG expression (Chen et al. 2002; He et al. 2002; Ghanem et al. 2008). In order to understand the senescence process and to determine the differences between developmental senescence and stress-induced senescence, it is important to clarify the functions of genes whose expression is induced by senescence.

Chlorophyll fluorescence imaging (measuring Fv/Fm) is a useful and non-invasive technique to assess the photosynthetic performance in leaves. A reduction in Fv/Fm value indicates lower PSII activity and is related to damage to the photosystem (Barbagallo et al. 2003). PSII activity has been shown to decrease during the senescence period (Fan et al. 1997; Lu et al. 2001; Breeze et al. 2008). Technological advances and improved understanding of chlorophyll fluorometry have contributed to the broader use of this technique to measure photosynthetic activity at cellular and sub-cellular levels in real time (Barbagallo et al. 2003; Li et al. 2006). For example, chlorophyll fluorescence has been used to investigate the heterogeneous pattern of performance in leaves during abiotic stresses such as suboptimal temperature and drought (Haldimann et al. 1996; Li et al. 2006).

According to previous work, exogenous auxin treatment may retard (Ellis et al., 2005) or accelerate senescence (Gören and Çağ 2007; Karatas et al. 2010; Sağlam-Çağ and Okatan 2014) in leaves and/or cotyledons. Currently, only fragmentary information is available on the effect of exogenous auxin application on leaf senescence and the effect of auxin on gene expression during senescence has not been investigated either. Therefore, in this study, we performed microarray analysis to investigate the effects of IAA treatment on the rate of senescence and on gene expression in leaves of different ages. Chlorophyll fluorescence imaging was also carried out on IAA-treated leaves as a marker of PSII activity to monitor photosynthetic performance during the senescence process.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

Arabidopsis Col-0 seeds were stratified for 48 h at 4 °C and then planted in an Arabidopsis soil mix (six parts Levingtons F2: one part dried silica sand: one-part vermiculite). Plants were grown under 16/8 h light/dark cycle at 22 °C and 70% relative humidity under 250 µmol m−2 s−1 light. The eighth rosette leaf was tagged with cotton thread between days 24 and 25 after sowing. Plants were sprayed with 10 µM IAA (Sigma) (dissolved in 0.1% ethanol) or 0.1% ethanol as a control (CT) at 3 different time points (27, 31 or 35 DAS = Days After Sowing). In each case, the eighth leaf was harvested 4 h after spraying for microarray analysis (2 replicates of 5 pooled leaves). Following the spraying, chlorophyll fluorescence of the eighth leaf from 8 additional replicate plants was measured daily (every 24 h).

Measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

Chlorophyll fluorescence imaging is a useful and non-invasive technique to measure photosynthetic activity at the cellular and subcellular levels in real time and at low light levels (Barbagallo et al. 2003; Li et al. 2006). Images of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were obtained essentially as described by Barbagallo et al. (2003) and Baker and Rosenqvist (2004) using a Cf Imager chlorophyll fluorescence imaging system (Technologica Ltd, Colchester, UK). Plants were dark-adapted for 15 min before Fo, the minimal fluorescence was measured using weak measuring pulses. Then, Fm, the maximal fluorescence, was measured during a 800 ms exposure to a saturating pulse of approximately 6300 µmol m−2 s−1. The plants were then exposed to an actinic PPFD of 250 µmol m−2 s−1 for 10 min and F’ was continuously monitored while Fm of the leaves in actinic light, was monitored after 10 min by applying a saturating light pulse. Following the spraying, chlorophyll fluorescence of the eighth leaf from 8 replicate plants was measured daily (every 24 h). Data were presented as mean ± standard errors.

Microarray experiments

For the microarray hybridization, total RNA was isolated from each leaf 8 harvested 4 h after spray treatments, using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and purified using a Qiagen RNA purification kit (Qiagen). The concentration of RNA was measured by using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. The integrity of RNA was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer System. 1 µg of total RNA was amplified using a MessageAmp II aRNA amplification kit (Ambion) in accordance with the kit protocol with a single round of amplification. Cy3- and Cy5-labelled cDNA probes were prepared from 2 µg of aRNA using a CyScribe Post-labelling kit (Amersham Biosciences). CATMA arrays (Allemeersch et al. 2005) were blocked in a solution of 5XSSC, 0.1% SDS and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 45 min at 42 °C and then washed in five changes of MilliQ water and twice in isopropanol. The two Cy-labelled cDNA probes were mixed in 25% formamide, 5XSSC, 0.1% SDS and 0.5 mg/ml yeast tRNA (Invitrogen) and hybridized to slides overnight at 42 °C. After hybridization for ~ 16 h, the slides were washed in 1XSSC/0.2% SDS for 10 min, 0.1XSSC/0.2% SDS for 2 × 10 min and then scanned using an Affymetrix 428 array scanner at 532 nm (Cy3) and 635 nm (Cy5). The scanned data were quantified using Imagene version 4.2 software (BioDiscovery). Imagene data were analysed by using GeneSpring version 5.1 (Silicon Genetics). Two biological replicates were collected from the samples, which were harvested 4 h after IAA application on days 27, 31, and 35 and labelled with Cy3 and Cy5. The resulting samples thus represented 2 biological replicates, each with two technical replicates (dye swaps). The data were combined in one GeneSpring experiment, and genes showing significant change in expression of at least two fold were identified. Differentially expressed genes were analysed in the Virtual Plant program (http://virtualplant.bio.nyu.edu) and gene ontologies were determined (Katari et al. 2010). The principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to show a difference in response between the different leaf stages. NTSYSpc version 2.1 was used for this analysis.

Results and discussion

The role of auxin in the control of leaf senescence has not been extensively studied. As summarised above, there are some reports that indicate a role in delaying senescence and some that show the opposite effect, depending on the plant species and tissue being examined. Mueller-Roeber and Balazadeh (2014) recently carried out a study investigating the expression of a group of auxin related genes selected from the literature, using senescence up or down regulated genes identified from the developmental senescence microarray analysis of Buchanan-Wollaston et al. (2005) and Breeze et al. (2011). They report a limited overlap between auxin and senescence regulated genes and conclude that auxin does not play a major role in direct regulation of gene expression during developmental senescence.

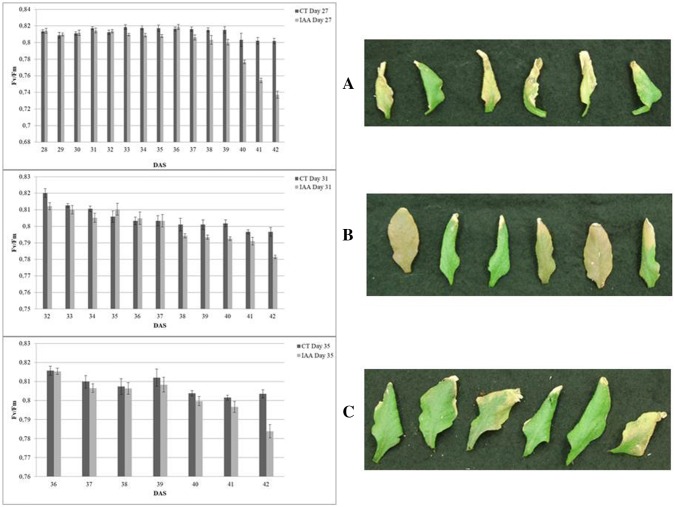

In this paper, we investigate the effects of IAA treatment of Arabidopsis plants at three different time points. Significant alterations in rates of senescence as well as in gene expression patterns were observed. In all cases, leaf 8 was used as the target leaf for chlorophyll fluorescence analysis and, from replicate plants, leaf 8 was sampled for gene expression analysis. Measurement of chlorophyll fluorescence showed a more rapid loss of photosynthetic capacity during senescence in the plants treated with IAA compared to the controls. This indicates that IAA treatment accelerates the progression of senescence-related changes. Interestingly, it appeared that treatment at the earliest timepoint, 27 DAS, caused the most significant acceleration of senescence but this was not manifested until later stages in the life of the leaf, at a similar time point as changes due to the treatment at 31 DAS started to be measurable (Fig. 2). Treatment at 27 DAS and at 31 DAS both resulted in a significant reduction in Fv/Fm values from 37 to 38 DAS onward, while treatment at 35 DAS did not show an obvious effect until the last sample time at 42 DAS, possibly indicating that there a less sensitive response to auxin in the older tissues.

Fig. 2.

Daily changes in Fv/Fm in IAA-treated leaves compared with controls. a Day27, b Day31 and c Day35 with images of harvested leaves 8th. Data showed that measurements of every 24 h after IAA treatment. Each value represents mean ± SE (n = 8)

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurement

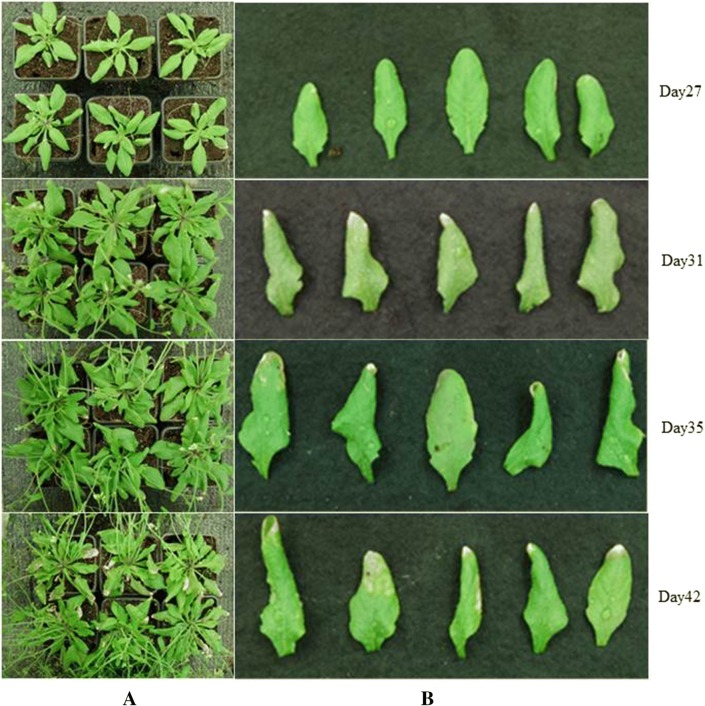

An important feature of the chlorophyll fluorescence measurement method is that the plant is not damaged during imaging and therefore it is possible to follow the change in fluorescence over time in the same leaf. Thus, since the early stage of senescence is not visible, the use of chlorophyll fluorescence measurement as a marker of PSII activity is a very sensitive method for detecting changes in metabolism and plant growth (Barbagallo et al. 2003; Breeze et al. 2008). In three independent experiments, following the spray treatments of replicate plants at days 27, 31, and 35 DAS, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in the 8th leaf of both the control and the IAA treated plants were measured daily to determine the maximum PSII activity. Figure 1a shows images of untreated plants at 27, 31, 35 and 42 DAS as well as examples of five harvested leaves (Fig. 1b). The changes in Fv/Fm in leaves treated with IAA were compared with controls (Fig. 2) and it is clear that the application of IAA on days 27, 31 and 35 had the same overall effect on the rate of leaf senescence. As senescence progressed, dark adapted PSII activity was seen to be significantly lower in all treated leaves than in the controls. Thus, senescence was accelerated at whatever age the leaves were when they were treated. However, images of IAA-treated 8th leaves at 42nd day showed that the earlier treatment with IAA (27 DAS) appears to have more of a significant visible effect on accelerating senescence than the later treatment.

Fig. 1.

a Images of untreated plants at 27, 31, 35 and 42 days after sowing (DAS). b Images of five examples of harvested Leaf 8

Gene expression analysis and Gene Ontologies

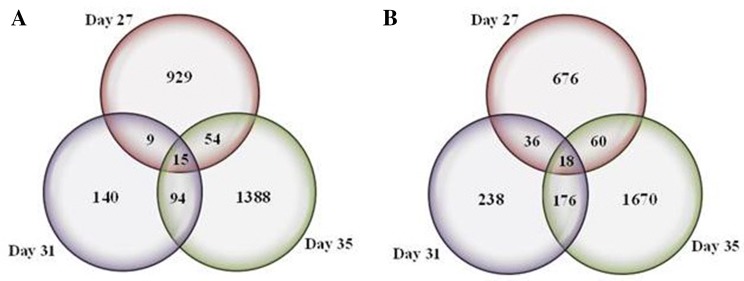

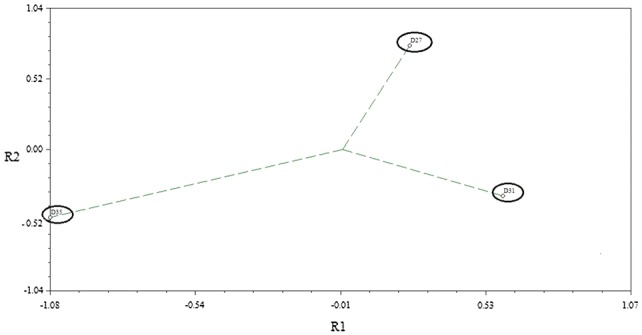

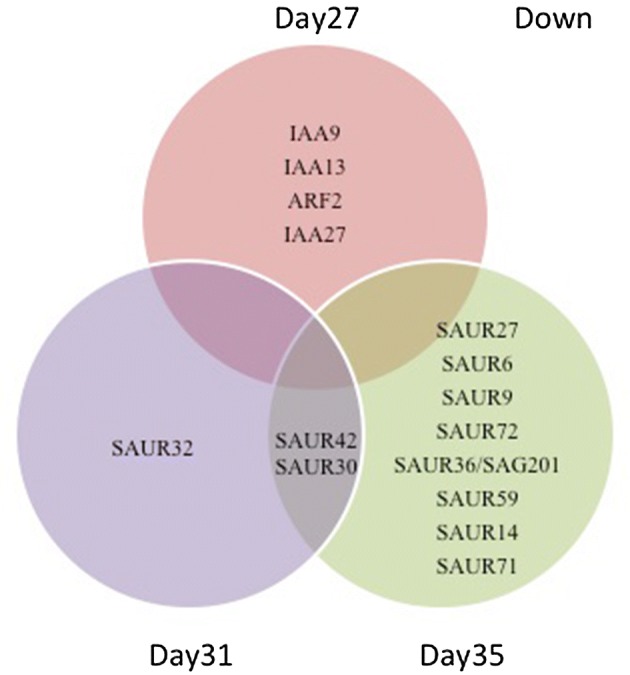

The microarray analysis showed clearly that extensive differential gene expression occurred following IAA treatment of the leaves at the three different ages (27, 31 and 35 DAS). PCA analysis was carried out to show that there was a significantly different response at the three timepoints (Fig. 3). In summary, IAA application to leaf 8 at 27 DAS resulted in significantly increased expression at least 2-fold of 1007 genes and decreased expression of 790 genes. Treatment of leaf 8 at 31 DAS resulted in 258 genes increased and 468 genes decreased in expression, and in leaf 8 treated at 35 DAS, 1551 genes were increased and 1924 genes decreased in expression. These groups of differentially expressed genes were used in Venn diagram analysis (Fig. 4) and this showed most of the identified genes were only differentially expressed at one of the timepoints, indicating very different responses due to leaf age.

Fig. 3.

Principal component analysis (PCA) diagram comparing gene expression differences following IAA treatment of leaves at different ages (27, 31 and 35 DAS)

Fig. 4.

Venn diagram analysis of differentially expressed genes following IAA treatment of leaves at 3 different ages (27, 31 and 35 DAS). Upregulated (a) and Downregulated (b) genes

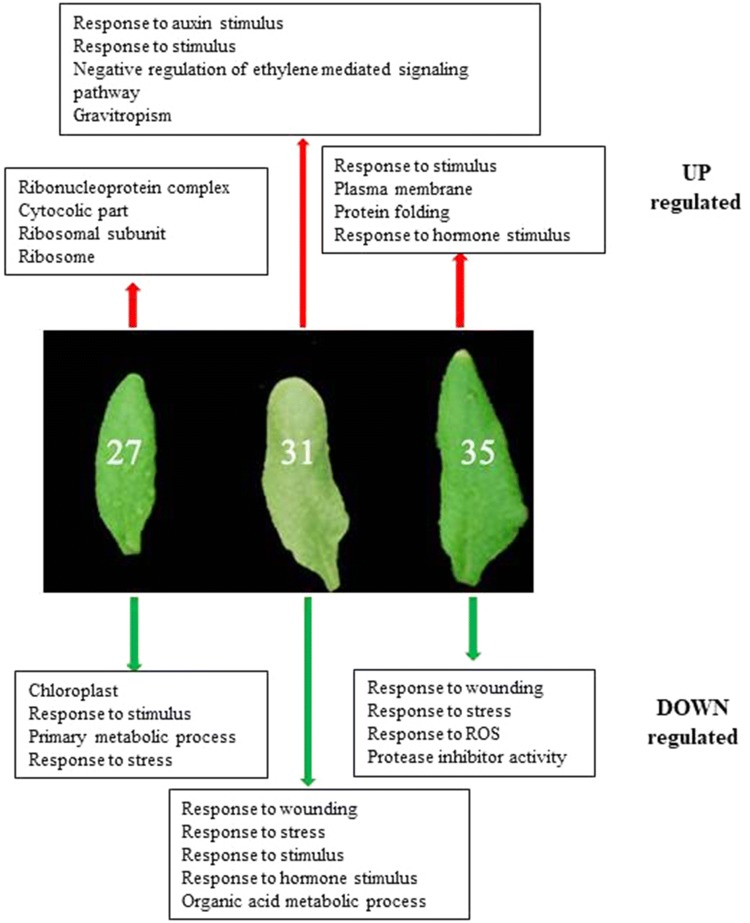

In order to compare potential metabolic or signalling pathways that may be altered following the IAA treatment in the different aged leaves, Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed on the up or downregulated genes identified at each timepoint. Figure 5 shows selected ontologies that were found to be significantly overrepresented for each treatment timepoint. The specific genes whose increasing or decreasing expressions contribute to the enrichment of these gene ontologies are shown in the Supplementary Table. Also, shown in this table is the previously reported relationship between the identified genes and expression during developmental senescence, which was analysed using gene expression data, published by Mueller-Roeber and Balazadeh (2014). The data reveal that there are significantly overrepresented gene ontologies, which differ depending on the age at which the leaf was treated with IAA (Fig. 5). Genes whose expression increased following treatment on day 27 are highly enriched with genes that play a key role in the ribosomal complex including genes encoding a number of 60 s and 40 s ribosomal proteins (Supplementary Table). Moreover, at day 27 two genes, At1g08780 (AIP3) and At5g23290 (PDF5), belonging to PREFOLDIN gene family involved in salt and cold stress responses, (Rodríguez-Milla and Salinas 2009; Perea-Resa et al. 2017) were found to be upregulated.

Fig. 5.

Enriched Gene Ontologies related to metabolic processes identified in the genes showing increased (UP regulated) or decreased (DOWN regulated) expression after IAA treatment at 27, 31 and 35 DAS

IAA spraying on day 31, resulted in increased expression of genes that play a role in response to auxin stimulus which included several IAA genes and also ARGOS (At3g59900), a gene associated with organ size and involved in abiotic stress responses in plants (Zhao et al. 2017). OsARGOS has been studied in transgenic rice lines which show altered ethylene-related phenotypes for root and coleoptile growth and senescence (Rai et al. 2015). Responses to ethylene in Arabidopsis thaliana are mediated by a family of five receptors called ETHYLENE RESPONSE1 (ETR1), ETR2, ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE4 (EIN4), ETHYLENE RESPONSE SENSOR1 (ERS1), and ERS2 (Wilson et al. 2014). Our data also show that two of these genes, ETR2 (At3g23150) and ERS2 (At1g04310), as well as EBF2 (At5g25350) were all determined as “SAGs” in previous work (Mueller-Rober and Balazadeh 2014) and associated with ethylene signaling are increased in expression in treated leaves at day 31 (Supplementary Table).

In the list of genes that showed enhanced expression at day 35, genes that play a role in response to stimulus and protein folding metabolic pathways were specifically enriched (Fig. 5 and Supplementary table). This included a number of heat shock proteins, ATHSP90.1 (At5g52640), HSP70 (At3g12580), HSP81-2 (At5g56030), HSP81-3 (At5g56010), a DNAJ heat shock protein C76 (At5g23240) and other genes involved in protein folding such as Calreticulin 3 (At1g08450). DNAJ/J-domain proteins are known as co-chaperones working in association with HSP70 (Petti et al. 2014). Also, At1g56600 (AtGolS2) was upregulated on day 35. It encodes a galactinol synthase that catalyzes the formation of galactinol from UDP-galactose and myoinositol. It was reported that heat shock factors related to galactinol levels (Song et al. 2016) and plants over-expressing GolS2 have increased tolerance to salt, chilling, and high-light stress. Our data also showed that At3g22840 (ELIP1) is upregulated on day 35. It has a function in chlorophyll binding and controls free chlorophyll levels (Casazza et al. 2005; Yao et al. 2015). It is up-regulated quickly and transiently by light and under a variety of stresses (Jones et al. 2016).

Investigation of enriched ontologies in genes showing down regulation following IAA treatment showed that treatment at 27 DAS resulted in decreased expression of genes related to chloroplast, response to stimulus, and primary metabolic processes (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table). Within these genes are several that have been shown to have a role in abiotic stress responses including JA and ABA signalling. For example, NCED4 (At4g19170) is involved in ABA biosynthesis, NAC family transcription factors play important roles in senescence (Wu et al. 2012; Mueller-Roeber and Balazadeh 2014; Li et al. 2018). Two members of this family, ANAC019 (At1g52890) and ANAC055 (At3g15500), were downregulated at day 27. During developmental senescence, these genes are involved in overlapping JA and ABA signalling pathways (Hickman et al. 2013; Sanjari et al. 2019) and their expression is enhanced by age, dark and ABA and meJA (Kim et al. 2018).

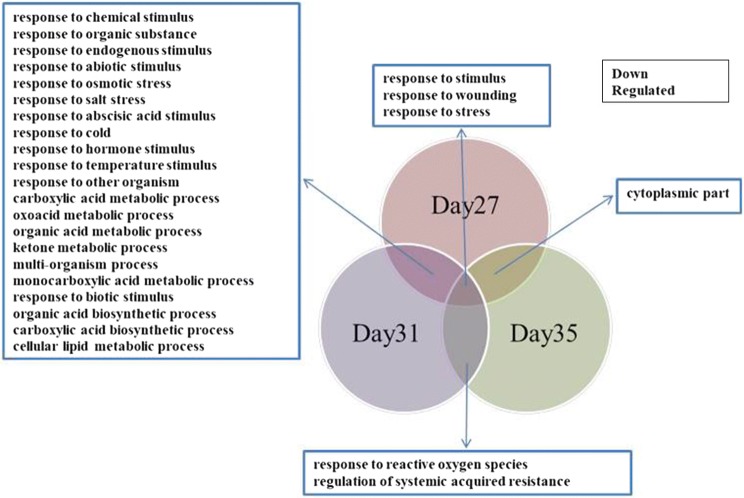

Treatment with IAA at day 31 resulted in down regulation of genes enriched in ontologies related to response to wounding and hormone stimulus. Similar to what was reported above for the 27 DAS treated leaves, included were many additional genes involved in JA biosynthesis, such as ALLENE OXIDE SYNTHASE (At5g42650) and LOX3 (At1g17420), and JA signalling such as JAZ10 (At5g13220). Similarly enrichment for genes involved in wounding, response to stress and response to ROS was also seen following IAA treatment of leaves 35 DAS and again JA signalling regulatory genes such as JAZ10 and JAZ2 are found in the group of down regulated genes.

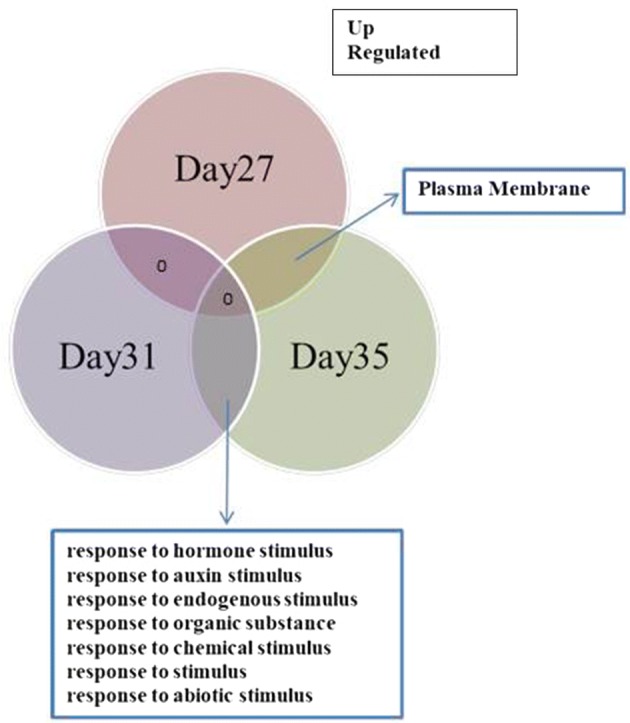

To investigate potential overlapping genes in the upregulated or downregulated groups, enriched gene ontologies in the groups of differentially expressed genes overlapping two or three timepoints were also identified. Figures 6 and 7 show gene ontologies for overlapping up and down regulated genes respectively. Enrichment of genes for hormone, auxin and abiotic stress stimulus is seen in the genes upregulated at 31 and 35 DAS. This includes BRU6 (At4g37390), a gene encoding indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase (Supplementary Table), induced during developmental senescence (Mueller-Roeber and Balazadeh 2014) which has a role as a negative component in auxin signalling by regulating auxin activity (Goda et al. 2004; Sghaier et al. 2018).

Fig. 6.

Venn diagram analysis of overlapping up-regulated gene ontologies after IAA treatment at 27, 31 and 35 DAS

Fig. 7.

Venn diagram analysis of overlapping down-regulated gene ontologies after IAA treatment at 27, 31 and 35 DAS

GO analysis of the overlapping groups of down regulated genes again highlighted enrichment of functions such as response to stress and hormone stimulus. ABI FIVE BINDING PROTEIN (At1g69260), a gene involved in the abscisic acid-activated signalling pathway (Lopez-Molina et al. 2003; Reeves et al. 2011; Ji et al. 2019; Ju et al. 2019), was downregulated at both 27 and 31 DAS. Overlapping genes downregulated at day 31 and day 35 included JASMONATE-ZIM-DOMAIN PROTEIN 10 (At5g13220), a gene involved in JA signalling which is upregulated during developmental senescence. As a general view, our data indicated that the majority of the genes downregulated at 31 and 35 DAS were identified as SAGs by Mueller-Roeber and Balazadeh (2014), i.e. upregulated during developmental senescence (Supplementary Table).

There were 15 overlapping genes showing increased expression at all three timepoints and 18 overlapping genes between all three downregulated datasets. These two groups of overlapping genes, upregulated and downregulated, are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Also shown is the previously reported relationship between the identified genes and expression during developmental senescence, which was analysed using gene expression data published by Mueller-Roeber and Balazadeh (2014). A key gene found in the overlapping group of upregulated genes is IAA4/AUXIN-INDUCIBLE 2-11 (At5g43700), which encodes an auxin inducible transcription factor and has been used as a marker for early auxin responses (Wyatt et al. 1993). The group of genes showing downregulation in all three treatments reveals more about changes in hormone signalling pathways. For example, RESPONSE REGULATOR 4 (ARR4, At1g10470) is a gene whose expression is induced by cytokinin which is downregulated during senescence. Also, ANAC055 (described above), an additional JAZ encoding gene, JAZ9 (At1g70700) and LOX4 (At1g72520), all of which have a role in JA signalling and are upregulated during developmental senescence, are downregulated following IAA treatment at all leaf ages.

Table 1.

Genes that show enhanced expression following IAA treatment at all three timepoints (Day27, Day31 and Day35)

| AGI | Annotation | Genes induced during developmental senescence (senescence-associated genes, SAGs) | Genes downregulated during developmental senescence (SDGs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| At3g26960 | Pollen Ole e 1 allergen and extensin family protein | − | + |

| At5g05960 | Bifunctional inhibitor/lipid-transfer protein/seed storage 2S albumin superfamily protein | − | − |

| At5g35970 | P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases superfamily protein | − | − |

| At2g32560 | F-box family protein | − | + |

| At3g52340 | SUCROSE-PHOSPHATASE 2 (SPP2) | − | − |

| At4g18250 | Receptor Serine/Threonine kinase-like protein | − | − |

| At1g59740 | NRT1/PTR FAMILY 4.3 | − | − |

| At5g65920 | ARM repeat superfamily protein | − | − |

| At5g37050 | Hypothetical protein | − | − |

| At5g43700 | INDOLE-3-ACETIC ACID INDUCIBLE 4/AUXIN INDUCIBLE 2-11 | − | − |

| At2g31110 | TRICHOME BIREFRINGENCE-LIKE 40 | + | − |

| At5g22580 | Stress responsive A/B Barrel Domain-containing protein | − | + |

| At5g13400 | Proton-dependent oligopeptide transport (POT) family protein | − | + |

| At4g33050 | EMBRYO SAC DEVELOPMENT ARREST 39 | + | − |

| At1g75500 | USUALLY MULTIPLE ACIDS MOVE IN AND OUT TRANSPORTERS 5 | − | + |

The previously reported relationship between the genes and senescence related expression was investigated using Mueller-Roeber and Balazadeh (2014) and column three and four indicate whether each gene was identified in this paper as being a senescence-associated gene (SAGs) or senescence downregulated gene (SDG), marked as (+) and (−), respectively

Table 2.

Genes that show reduced expression following IAA treatment at all three timepoints (Day27, Day31 and Day35)

| AGI | Annotation | Genes induced during developmental senescence (senescence-associated genes, SAGs) | Genes downregulated during developmental senescence (SDGs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| At1g10470 | RESPONSE REGULATOR 4 (ARR4) | − | + |

| At1g20030 | Pathogenesis-related thaumatin superfamily protein | − | − |

| At1g52770 | Phototropic-responsive NPH3 family protein | − | + |

| At1g70700 | JASMONATE-ZIM-DOMAIN PROTEIN 9 | + | − |

| At1g72520 | LIPOXYGENASE 4 | + | − |

| At1g77490 | THYLAKOIDAL ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE (TAPX) | − | + |

| At2g28120 | OVARIAN TUMOR DOMAIN (OTU)-CONTAINING DUB (DEUBIQUITILATING ENZYME) 1 | + | − |

| At2g28570 | Hypothetical protein | − | − |

| At3g15500 | NAC DOMAIN CONTAINING PROTEIN 55 | + | − |

| At3g28300 | Integrin-related protein 14a (AT14A) | − | + |

| At4g15210 | BETA-AMYLASE 5 | − | + |

| At4g22470 | Protease inhibitor/seed storage/lipid transfer protein (LTP) family protein | + | − |

| At4g34710 | ARGININE DECARBOXYLASE 2 | + | − |

| At4g36830 | GNS1/SUR4 membrane protein family | − | − |

| At5g23210 | SERINE CARBOXYPEPTIDASE-LIKE 34 | − | − |

| At5g28237 | Pyridoxal-5-phosphate-dependent enzyme family protein | + | − |

| At5g40890 | CHLORIDE CHANNEL PROTEIN A | − | + |

| At5g60850 | OBF BINDING PROTEIN 4 | − | − |

The previously reported relationship between the genes and senescence related expression was investigated using Mueller-Roeber and Balazadeh (2014) and column three and four indicate whether each gene was identified in this paper as being a senescence-associated gene (SAGs) or senescence downregulated gene (SDG), marked as (+) and (−), respectively

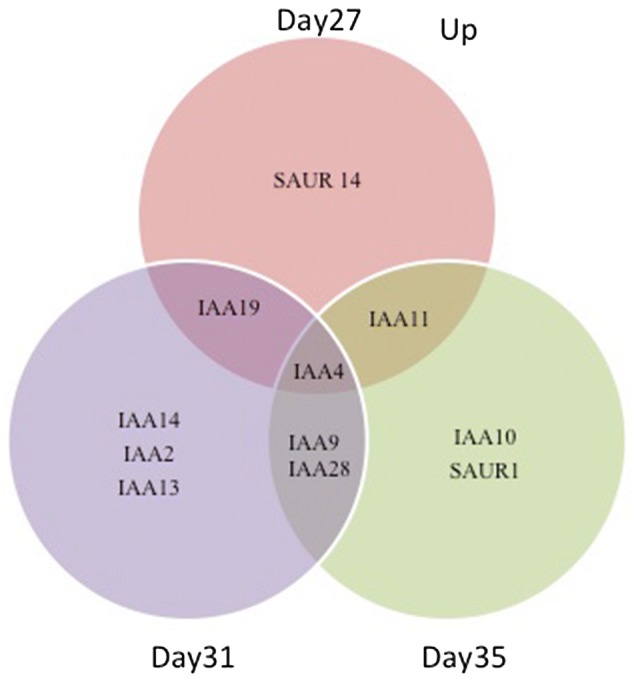

To further investigate the effects of the IAA treatment on expression of other known auxin response genes, we analysed our microarray data specifically for expression of SAURS (small auxin-upregulated RNA genes) and AUX/IAA genes (Figs. 8 and 9). This showed that apart from the increased expression of IAA4/AUXIN-INDUCIBLE 2-11 (At5g43700) at all three timepoints, many other auxin related genes were differentially expressed following treatments (Figs. 8 and 9). Particularly striking is the observation that although many AUX/IAA genes show increased expression after treatment, many SAUR genes were down regulated following treatment especially in older leaves at Day35 (Fig. 9). Researchers showed that transcription of the AUX/IAA family of genes is rapidly increased by auxin (Rouse et al. 1998; Thakur et al. 2005; Jung et al. 2015).

Fig. 8.

Venn diagram analysis of overlapping up-regulated SAURs and AUX/IAA genes after IAA treatment at 27, 31 and 35 DAS

Fig. 9.

Venn diagram analysis of overlapping down-regulated SAURs and AUX/IAA genes after IAA treatment at 27, 31 and 35 DAS

To test the effect of IAA treatment on gene expression, we used microarray analysis. Leaves of the three different ages were harvested 4 h after treatment and extensive gene expression changes were observed at all three timepoints. The IAA treatment resulted in increased expression of a number of genes known to be auxin inducible, showing the effectiveness of the auxin treatment. These genes included the auxin marker gene, IAA4 which was seen in all groups of upregulated genes and BRU6 (At4g37390), a gene encoding indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase which catalyses the formation of auxin amino acid conjugates and has been postulated to enable the plant to cope with excess auxin. The specific analysis of the auxin related genes AUX/IAA and SAUR, shown in Figs. 8 and 9, also show that there was alteration in expression of many of these at each of the timepoints. This analysis shows that the IAA treatment had the expected effect and validates the microarray analysis.

Conclusion

Interestingly, the age of the leaf at the time of treatment made a considerable difference to the response at the gene expression level. Gene ontology analysis showed that there were different metabolic pathways enriched at each timepoint. For example, at day 27, specific upregulation of ribosomal related genes could be an indication that the leaf can still respond to auxin induction of growth. This effect is no longer seen in older leaves indicating that these have lost the ability for further growth. At 31 DAS, the main pathways upregulated were the auxin inducible IAA genes but also genes involved in ethylene responses. Increased ethylene signalling could be the cause of the enhanced rate of senescence seen in the treated tissues. At the same time, genes involved in ABA and JA biosynthesis and signalling responses were downregulated. Cross talk between hormone signalling pathways during senescence is very complex and not understood. Many stress related pathways involving JA, SA, ABA and ethylene are induced during developmental senescence, possibly as a protection mechanism and so perturbation of this balance by treatment with auxin could result in early onset of senescence. Crosstalk between JA, ethylene and auxin during developmental senescence has been discussed by Hu et al. (2017) who suggested opposing functions of JA and auxin in leaf senescence.

Previous studies on the relationship between auxin and senescence have mostly been physiological analyses and have not investigated gene expression at the single leaf-based level. Our results that IAA application caused significant changes in gene expression patterns 4 h after treatment and these were dependent on the age of the leaf. Consequent effects on senescence were studied at the physiological level and significant acceleration of senescence was visible several days after treatment. However, further molecular studies at more timepoints after treatment would reveal more about the downstream effects of the IAA treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Table: Gene Ontology analysis of genes differentially expressed following IAA treatment. The previously reported relationship between the genes and senescence related expression was investigated using Mueller-Roeber and Balazadeh (2014) and column D and E indicate whether each gene was identified in this paper as being a senescence-associated gene (SAGs) or senescence downregulated gene (SDG), marked as (+) and (-), respectively. A: Genes within Ontology groups that were identified as being overrepresented amongst genes showing increased expression at following IAA treatment at 27, 31 and 35 DAS. B: Genes within Ontology groups that were identified as being overrepresented amongst genes showing decreased expression at following IAA treatment at 27, 31 and 35 DAS (XLSX 22 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work is part of N.G-S’ PhD. thesis.

Author contributions

N.G.-S., V.B.-W., E.H., E.B. and G.Ö designed the research; N.G.-S. did the experimental work, performed data analysis, wrote the paper, revised manuscript discussed with V.B.-W.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Allemeersch J, Durinck S, Vanderhaeghen R, Alard P, Maes R, Seeuws K, et al. Benchmarking the catma microarray: a novel tool for Arabidopsis transcriptome analysis. Plant Physiol. 2005;137:588–601. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.051300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NR, Rosenqvist E. Applications of chlorophyll fluorescence can improve crop production strategies: an examination of future possibilities. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:1607–1621. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazadeh S. Stay-green not always stays green. Mol Plant. 2014;7:1264–1266. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbagallo RP, Oxborough K, Pallett KE, Baker NR. Rapid, noninvasive screening for perturbations of metabolism and plant growth using chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:485–493. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.018093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashri G, Prasad SM. Exogenous IAA differentially affects growth, oxidative stress and antioxidants system in Cd stressed Trigonella foenum-graecum L. seedlings: toxicity alleviation by up-regulation of ascorbate-glutathione cycle. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2016;132:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeze E, Harrison E, Page T, Warner N, Shen C, Zhang C, Buchanan-Wollaston V. Transcriptional regulation of plant senescence: from functional genomics to systems biology. Plant Biol. 2008;10:99–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeze E, Harrison E, McHattie S, Hughes L, Hickman R, Hill C, et al. High-resolution temporal profiling of transcripts during Arabidopsis leaf senescence reveals a distinct chronology of processes and regulation. Plant Cell. 2011;23:873–894. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.083345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan-Wollaston V, Earl S, Harrison E, Mathas E, Navabpour S, Page T, Pink D. The molecular analysis of leaf senescence—a genomics approach. Plant Biotechnol J. 2003;1:3–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-7652.2003.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan-Wollaston V, Page T, Harrison E, Breeze E, Lim PO, Nam HG, et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals significant differences in gene expression and signalling pathways between developmental and dark/starvation-induced senescence in Arabidopsis. The Plant J. 2005;42:567–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casazza AP, Rossini S, Rosso MG, Soave C. Mutational and expression analysis of ELIP1 and ELIP2 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;58:41–51. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-4090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamarro J, Östin A, Sandberg G. Metabolism of indole-3-acetic acid by orange (Citrus sinensis) flavedo tissue during fruit development. Phytochemistry. 2001;57(179):187. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Provart NJ, Glazebrook J, Katagiri F, Chang HS, Eulgem T, et al. Expression profile matrix of Arabidopsis transcription factor genes suggests their putative funcions in response to environmental stresses. Plant Cell. 2002;14:559–574. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Michele R, Vurro E, Rigo C, Costa A, Elviri L, Di Valentin M, et al. Nitric oxide is involved in cadmium-induced programmed cell death in Arabidopsis suspension cultures. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:217–228. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.133397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CM, Nagpal P, Young JC, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ, Reed JW. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR1 and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2 regulate senescence and floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2005;132:4563–4574. doi: 10.1242/dev.02012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Zheng S, Wang X. Antisense suppression of phospholipase D alpha retards abscisic acid-and ethylene-promoted senescence of postharvest Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Cell. 1997;9:2183–2196. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.12.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farage-Barhom S, Burd S, Sonego L, Perl-Treves R, Lers A. Expression analysis of the BFN1 nuclease gene promoter during senescence, abscission, and programmed cell death-related processes. J Exp Bot. 2008;59:3247–3258. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AM (2007) Nutrient remobilization during leaf senescence. In: Gan S (ed) Annual plant reviews volume 26: senescence processes in plants. 10.1002/9780470988855.ch5

- Ghanem ME, Albacete A, Martínez-Andújar C, Acosta M, Romero-Aranda R, Dodd IC, et al. Hormonal changes during salinity-induced leaf senescence in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) J Exp Bot. 2008;59:3039–3050. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda H, Sawa S, Asami T, Fujioka S, Shimada Y, Yoshida S. Comprehensive comparison of auxin-regulated and brassinosteroid-regulated genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1555–1573. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.034736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gören N, Çağ S. The effect of Indole-3-acetic acid and benzyladenine on sequential leaf senescence on Helianthus annuus L. seedlings. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2007;21:322–327. [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen PL, Culetic A, Boschian L, Krupinska K. Plant senescence and crop productivity. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;82:603–622. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldimann P, Fracheboud Y, Stamp P. Photosynthetic performance and resistance to photoinhibition of Zea mays L. leaves grown at sub-optimal temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 1996;19:85–92. [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Fukushige H, Hildebrand DF, Gan S. Evidence supporting a role of jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:876–884. doi: 10.1104/pp.010843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman R, Hill C, Penfold CA, Breeze E, Bowden L, Moore JD, et al. A local regulatory network around three NAC transcription factors in stress responses and senescence in Arabidopsis leaves. The Plant J. 2013;75:26–39. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Jiang Y, Han X, Wang H, Pan J, Yu D. Jasmonate regulates leaf senescence and tolerance to cold stress: crosstalk with other phytohormones. J Exp Bot. 2017;68:1361–1369. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H, Wang S, Cheng C, Li R, Wang Z, Jenkins GI, et al. The RCC 1 family protein SAB 1 negatively regulates ABI 5 through multidimensional mechanisms during postgermination in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2019;222:907–922. doi: 10.1111/nph.15653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Liang G, Yang S, Yu D. Arabidopsis WRKY57 functions as a node of convergence for jasmonic acid-and auxin-mediated signaling in jasmonic acid-induced leaf senescence. Plant Cell. 2014;26:230–245. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.117838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jibran R, Hunter DA, Dijkwel PP. Hormonal regulation of leaf senescence through integration of developmental and stress signals. Plant Mol Biol. 2013;82:547–561. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DC, Zheng W, Huang S, Du C, Zhao X, Yennamalli RM, et al. A clade-specific Arabidopsis gene connects primary metabolism and senescence. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:983–987. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju L, Jing Y, Shi P, Liu J, Chen J, Yan J, et al. JAZ proteins modulate seed germination through interaction with ABI 5 in bread wheat and Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2019;223:246–260. doi: 10.1111/nph.15757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Lee DK, Do Choi Y, Kim JK. OsIAA6, a member of the rice Aux/IAA gene family, is involved in drought tolerance and tiller out growth. Plant Sci. 2015;236:304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jusoh M, Loh SH, Chuah TS, Aziz A, San Cha T. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) induced changes in oil content, fatty acid profiles and expression of four fatty acid biosynthetic genes in Chlorella vulgaris at early stationary growth phase. Phytochemistry. 2015;111:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatas I, Ozturk L, Ersahin Y, Okatan Y. Effects of auxin on photosynthetic pigments and some enzyme activities during dark-induced senescence of Tropaeolum leaves. Pak J Bot. 2010;42(3):1881–1888. [Google Scholar]

- Katari MS, Nowicki SD, Aceituno FF, Nero D, Kelfer J, Thompson LP, et al. VirtualPlant: a software platform to support systems biology research. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:500–515. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.147025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kim JH, Lyu J, Woo HR, Lim PO. New insights into regulation of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2018;69:787–799. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li RH, Guo PG, Michael B, Stefania G, Salvatore C. Evaluation of chlorophyll content and fluorescence parameters as indicators of drought tolerance in barley. Agr Sci China. 2006;5:751–757. [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Li X, Chao J, Zhang Z, Wang W, Guo Y. NAC family transcription factors in tobacco and their potential role in regulating leaf senescence. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1900–1915. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim PO, Nam HG. Aging and senescence of the leaf organ. J Plant Biol. 2007;50:291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Lim PO, Kim HJ, Nam HG. Leaf senescence. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:115–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Molina L, Mongrand S, Kinoshita N, Chua NH. AFP is a novel negative regulator of ABA signaling that promotes ABI5 protein degradation. Genes Dev. 2003;17:410–418. doi: 10.1101/gad.1055803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Lu Q, Zhang J, Kuang T. Characterization of photosynthetic pigment composition, photosystem II photochemistry and thermal energy dissipation during leaf senescence of wheat plants grown in the field. J Exp Bot. 2001;52:1805–1810. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.362.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris K, Mackerness SAH, Page T, John CF, Murphy AM, Carr JP, Buchanan-Wollaston V. Salicylic acid has a role in regulating gene expression during leaf senescence. The Plant J. 2000;23:677–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller-Roeber B, Balazadeh S. Auxin and its role in plant senescence. J Plant Growth Regul. 2014;33:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Perea-Resa C, Rodríguez-Milla MA, Iniesto E, Rubio V, Salinas J. Prefoldins negatively regulate cold acclimation in Arabidopsis thaliana by promoting nuclear proteasome-mediated HY5 degradation. Mol Plant. 2017;10:791–804. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petti C, Nair M, DeBolt S. The involvement of J-protein AtDjC17 in root development in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:532–541. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai MI, Wang X, Thibault DM, Kim HJ, Bombyk MM, et al. The ARGOS gene family functions in a negative feedback loop to desensitize plants to ethylene. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:157. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0554-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves WM, Lynch TJ, Mobin R, Finkelstein RR. Direct targets of the transcription factors ABA-Insensitive (ABI) 4 and ABI5 reveal synergistic action by ABI4 and several bZIP ABA response factors. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;75:347–363. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9733-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Milla MA, Salinas J. Prefoldins 3 and 5 play an essential role in Arabidopsis tolerance to salt stress. Mol Plant. 2009;2:526–534. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse D, Mackay P, Stirnberg P, Estelle M, Leyser O. Changes in auxin response from mutations in an AUX/IAA gene. Science. 1998;279:1371–1373. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5355.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sağlam-Çağ S, Okatan Y. The effects of zinc (Zn) and C14-indoleacetic acid (IAA) on leaf senescence ın Helianthus annuus L. Int J Plant Physiol Biochem. 2014;6:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjari S, Shirzadian-Khorramabad R, Shobbar Z-S, Shahbazi M. Systematic analysis of NAC transcription factors’ gene family and identification of post-flowering drought stress responsive members in sorghum. Plant Cell Rep. 2019;38:361–376. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwat M, Naqvi AR, Ahmad P, Ashraf M, Akram NA. Phytohormones and microRNAs as sensors and regulators of leaf senescence: assigning macro roles to small molecules. Biotechnol Adv. 2013;31:1153–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sghaier N, Ayed RB, Gorai M, Rebai A. Prediction of auxin response elements based on data fusion in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Biol Rep. 2018;45:763–772. doi: 10.1007/s11033-018-4216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharabi-Schwager M, Samach A, Porat R. Overexpression of the CBF2 transcriptional activator in Arabidopsis suppresses the responsiveness of leaf tissue to the stress hormone ethylene. Plant Biol. 2010;12:630–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Chan Z. INDOLE- 3- ACETIC ACID INDUCIBLE 17 positively modulates natural leaf senescence through melatonin- mediated pathway in Arabidopsis. J Pineal Res. 2015;58:26–33. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C, Chung WS, Lim CO. Overexpression of heat shock factor gene HsfA3 increases galactinol levels and oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Mol Cells. 2016;39:477–479. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava LM. Plant growth and development Hormones and Environment. California: Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur JK, Jain M, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP. Exogenous auxin enhances the degradation of a light down-regulated and nuclear-localized OsiIAA1, an Aux/IAA protein from rice, via proteasome. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Struct Expr. 2005;1730:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda H, Kusaba M. Strigolactone regulates leaf senescence in concert with ethylene in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:138–147. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Graaff E, Schwacke R, Schneider A, Desimone M, Flügge UI, Kunze R. Transcription analysis of Arabidopsis membrane transporters and hormone pathways during developmental and induced leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:776–792. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R, Kim H, Bakshi A, Binder B. The ethylene receptors, ETHYLENE RESPSONE 1 and 2, have contrasting roles in seed germination of Arabidopsis thaliana during salt stress. Plant Physiol. 2014;165:1353–1366. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.241695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu A, Allu AD, Garapati P, Siddiqui H, et al. JUGBURUNNEN1, a reactive oxygen species-responsive NAC transcription factor, regulates longevity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:482–506. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.090894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- www.arabidopsis.org. Accessed 10 April 2019

- Wyatt RE, Ainley WM, Nagao RT, Conner TW, Key JL. Expression of the Arabidopsis AtAux2-11 auxin-responsive gene in transgenic plants. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;22:731–749. doi: 10.1007/BF00027361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y, Umehara M. Possible roles of strigolactones during leaf senescence. Plants. 2015;4:664–677. doi: 10.3390/plants4030664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y, Furusawa S, Nagasaka S, Shimomura K, Yamaguchi S, Umehara M. Strigolactone signaling regulates rice leaf senescence in response to a phosphate deficiency. Planta. 2014;240:399–408. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, You J, Ou Y, Ma J, Wu X, Xu G. Ultraviolet-B protection of ascorbate and tocopherol in plants related with their function on the stability on carotenoid and phenylpropanoid compounds. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2015;90:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis and its role in plant development. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:49–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Tian X, Li Y, Zhang L, Guan P, Kou X, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of wheat ARGOS genes influencing plant growth and stress tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:170–177. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table: Gene Ontology analysis of genes differentially expressed following IAA treatment. The previously reported relationship between the genes and senescence related expression was investigated using Mueller-Roeber and Balazadeh (2014) and column D and E indicate whether each gene was identified in this paper as being a senescence-associated gene (SAGs) or senescence downregulated gene (SDG), marked as (+) and (-), respectively. A: Genes within Ontology groups that were identified as being overrepresented amongst genes showing increased expression at following IAA treatment at 27, 31 and 35 DAS. B: Genes within Ontology groups that were identified as being overrepresented amongst genes showing decreased expression at following IAA treatment at 27, 31 and 35 DAS (XLSX 22 kb)