Abstract

Wurfbainia villosa, which belongs to the huge family Zingiberaceae, is used in the clinic for the treatment of spleen and stomach diseases in southern China. The complete chloroplast genome of W. villosa was sequenced and analyzed using next-generation sequencing technology in the present work. The results showed that the W. villosa chloroplast genome is a circular molecule with 163,608 bp in length. It harbors a pair of inverted repeat regions (IRa and IRb) of 29,820 bp in length, which separate the large single copy (LSC, 88,680 bp) region and the small single copy (SSC, 15,288 bp) region. After annotation, 134 genes were identified in this plastome in total, comprising of 87 protein-coding genes, 38 transfer RNA genes, 8 ribosomal RNA genes and one pseudogene (ycf1). Codon usage, RNA editing sites and single/long sequence repeats were investigated to understand the structural characteristics of the W. villosa chloroplast genome. Furthermore, IR contraction and expansion were analyzed by comparison of complete chloroplast genomes of W. villosa and four other Zingiberaceae species. Finally, a phylogeny study based on the chloroplast genome of W. villosa, along with that of 15 different species, was conducted to further investigate the relationship among these lineages. Overally, our results represented the first insight into the chloroplast genome of W. villosa, and could serve as a significant reference for species identification, genetic diversity analysis and phylogenetic research between W. villosa and other species within Zingiberaceae.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12298-019-00748-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Wurfbainia villosa, Chloroplast genome, Structural characteristics, Phylogenetic study

Introduction

Zingiberaceae is a large monocotyledonous family comprising of more than 47 genera and 700 species, which are mainly distributed in tropical areas (Barbosa et al. 2017; Sharifi-Rad et al. 2017). This family consists of two major subfamilies, namely Costoideae and Zingiberoideae. In China, Zingiberaceae species are commonly found in thesouthern provinces, such as Guangdong, Guangxi, and Yunnan. Many Zingiberaceae species, such as Zingiber officinale (Ebrahimzadeh Attari et al. 2018), Amomum longiligularis (Amomum is equivalent to Wurfbainia), Amomum krevanh (Diao et al. 2014), and Wurfbainia villosa, are medicinal and ornamental plants (Taheri et al. 2019). Fruits of W. villosa are frequently used in medicine in China, as they offer several significant therapeutic effects, such as eliminating dampness, preventing miscarriage, warming the spleen, curing diarrhea, promoting appetite, and regulating the flow of Qi (in Traditional Chinese Medicine, Qi is the most fundamental, active substance that constitutes the body and maintains life activities) (Huang et al. 2014a, b; Tian et al. 2008). Therefore, W. villosa has gained increasing attention from researchers over the past decades.

Wurfbainia villosa is extremely scarce, owing to anthropogenic destruction of the environment, the impact of insects, and phytopathy. Because of its scarcity, adulterants of W. villosa have become prevalent in the market (Chen et al. 2001), including fruits of related Wurfbainia species and of unrelated species like Alpinia japonica (Thunb.) Miq (Zhu et al. 2017). Therefore, it is of great importance to perform studies on the molecular markers and phylogenic relationships between W. villosa and related species. The chloroplast genome offers abundant sequence information for biomarker screening and phylogenetic studies.

Chloroplasts are organelles directly related to plant photosynthesis, metabolism, and internal redox reactions. Research supports that chloroplasts are likely derived from cyanobacteria through an endosymbiotic event (Dyall et al. 2004). Typically, chloroplast genomes are conserved in size, ranging from 120 to 180 kb, and have a highly quadripartite structure for most angiosperms (Bendich 2004), consisting of two inverted repeats (IR) that separate the large single copy (LSC) region and the small single copy (SSC) region, forming the circular structure of the chloroplast genome. Furthermore, low frequencies of both nucleotide substitution and recombination are observed in reported chloroplast genomes (Wicke et al. 2011). Thus, chloroplast DNA sequences are generally used for the phylogenetic analysis of eukaryotic plants to resolve complex evolutionary relationships (Sudianto et al. 2019). Comparisons of entire plastome sequences provide effective resources for the development of variable markers (Dong et al. 2017). Since the first annotation of the tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) chloroplast genome (Yukawa et al. 2006), a large number of chloroplast genomes has been assembled and documented, owing to the rapid development of high-throughput sequencing technologies. The chloroplast is maternally inherited, making it ideal for studies on genetic diversity, development, and species identification.

Reports on the chloroplast genome sequences of Zingiberaceae species are extremely rare. In this study, the complete chloroplast genome sequence of W. villosa was obtained. Then, a comprehensive study was conducted on its structural characteristics and phylogenetic relationship with close species. This study aimed to provide abundant information for future studies on the evolutionary history and development of Zingiberaceae species.

Results and discussion

Chloroplast genome extraction

As known, there are two strategies for obtaining plastid genome, one is isolation of the plastid from all tissues and extraction of its DNA for sequencing and subsequent assembly while the other is isolation of genomic DNA for sequencing, extract plastid like reads for assembly (Chen et al. 2018). The first approach is conventional, but it is more difficult to isolate chloroplast genomes (Kerstin et al. 2008) whereas the second one applies to species that already have reference genomes. Furthermore, with the continuous progress of sequencing technology in recent years, based on the fact that chloroplast genome is more conservative and it is relatively easy to isolate chloroplast sequences through homology, the latter one seems to be more popular among researchers (Kim and Lee 2004; Wu et al. 2017), as there are abundant cases supporting use of this approach.

Accordingly, the total genomic DNA of Wurfbainia villosa was extracted in the early stage of this study, and then the chloroplast genome of the W. villosa was obtained by sequencing alignment, assembly and splicing with two closely relative chloroplast genomes of the Amomum compactum and Amomum kravanh. The plastome of our study exhibits wonderful similarity to its references, due to the conservation of plastid genome.

Structural characteristics

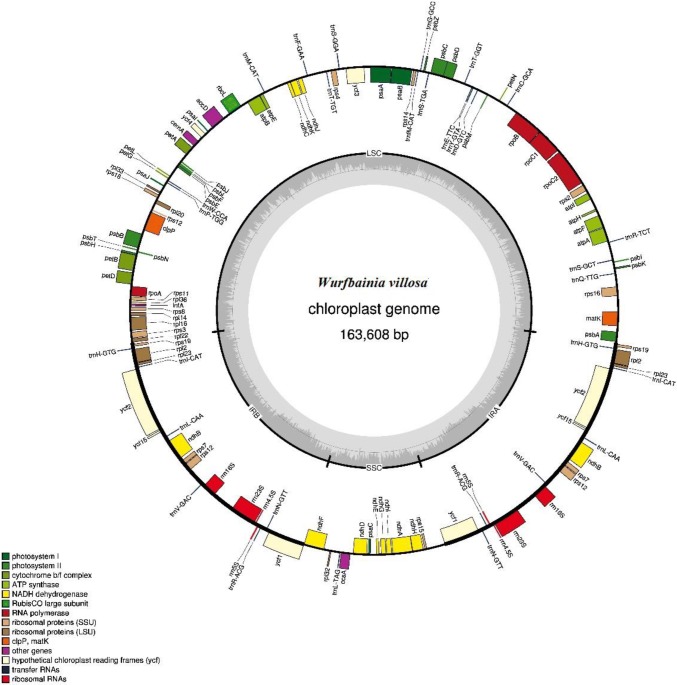

The whole chloroplast genome of W. villosa is a circular molecule with a typical quadripartite structure commonly observed for plant chloroplasts (Fig. 1). The plastome of W. villosa is 163,608 bp long, consisting of one large single copy (LSC) region of 88,680 bp in length, one small single copy (SSC) region of 15,288 bp in length, and a pair of inverted repeats (IRs) of 29,820 bp (Table 1). The overall size of the protein-coding sequence (CDS) is 76,113 bp. Additionally, the total GC content, which plays an important role in the evolution of the genome (Veleba et al. 2017), is 36.4% in the plastome of W. villosa, this GC content is unequally distributed. Specifically, the GC content in the IR region (41.1%) exhibits the highest value across the whole chloroplast genome, while the lowest value (30.1%) was observed in the SSC region. Furthermore, it was interesting to observe that the third codon position was highly represented, analogous to what has been found in other land plant chloroplast genomes (Shen et al. 2017). This phenomenon contributes to the differentiation between chloroplast, mitochondrial, and nuclear DNA (Clegg et al. 1994).

Fig. 1.

Gene map of the complete chloroplast genome of W. villosa. The genes inside the circle are clockwise transcribed while those outside the circle are opposite. The filled color portion labels the genes in the chloroplast genome according to the color corresponding to the legend at the bottom left. Dark gray circles indicate the GC content and light gray circles indicate the AT content

Table 1.

Base content in the chloroplast genome of W. villosa

| Regions | Positions | T (U) (%) | C (%) | A (%) | G (%) | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSC | 33.8 | 17.2 | 32.5 | 16.5 | 88,680 | |

| IRA | 30.1 | 21.3 | 28.7 | 19.8 | 29,820 | |

| SSC | 34.2 | 15.8 | 35.8 | 14.3 | 15,288 | |

| IRB | 28.7 | 19.8 | 30.1 | 21.3 | 29,820 | |

| Total | 32.2 | 18.3 | 31.7 | 18.1 | 163,608 | |

| CDS | 32.2 | 18.3 | 31.7 | 18.1 | 76,113 | |

| 1st position | 33.0 | 17.8 | 31.5 | 18.1 | 54,536 | |

| 2nd position | 32.0 | 19.0 | 30.8 | 18.3 | 54,536 | |

| 3rd position | 32.0 | 18.1 | 32.7 | 16.9 | 54,536 |

CDS protein-coding regions

After annotation, we identified 114 different genes encoded by the chloroplast genome of W. villosa, twenty of which are duplicated in the IR regions. The genome annotation revealed a total of 87 protein-coding genes, 38 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, eight ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, and one pseudogene (ycf1). In general, the chloroplast genome of W. villosa resembles its closely related species A. krevanh or A. compactum in terms of gene content and sequence (Wu et al. 2017, 2018). Among these predicted genes, 21 tRNA genes and 60 protein-coding genes are located in the LSC region, while only one tRNA and 11 protein-coding genes were identified in the SSC area. Furthermore, 7 protein-coding genes, including ndhB, rps7, rps12, rps19, rpl2, rpl23, and ycf2, were found to be duplicated (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Gene contents in the chloroplast of W. villosa

| No. | Group of genes | Gene names | Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ | 5 |

| 2 | Photosystem II | PsbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ | 15 |

| 3 | Cytochrome b/f complex | petA, petB*, petD*, petG, petL, petN | 6 |

| 4 | ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF*, atpH, atpI | 6 |

| 5 | NADH dehydrogenase | ndhA*, ndhB* (× 2), ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK | 12 (1) |

| 6 | RubisCO large subunit | rbcL | 1 |

| 7 | RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1*, rpoC2 | 4 |

| 8 | Ribosomal proteins (SSU) | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7 (× 2), rps8, rps11, rps12** (× 2), rps14, rps15, Rps16*, rps18, rps19 (× 2) | 15 (3) |

| 9 | Ribosomal proteins (LSU) | rpl2* (× 2), rpl14, rpl16*, rpl20, rpl22, rpl23 (× 2), rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 | 11 (2) |

| 10 | Proteins of unknown functions | ycf1 (× 2), ycf2 (× 2), ycf3*, ycf4 | 6 (2) |

| 11 | Transfer RNAs | 38tRNAs (6 contain an intron, 8 in the IRs) | 38 (8) |

| 12 | Ribosomal RNAs | rrn4.5S (× 2), rrn5S (× 2), rrn16S (× 2), rrn23S (× 2) | 8 (4) |

| 13 | Other genes | accD, c1pP**, matK, ccsA, cemA, infA | 6 |

| Total | 134 |

*Gene contains one intron

**Gene contains two introns; (× 2) indicates the number of the repeat unit is 2

In addition, 17 genes contain introns. Fourteen of them, including atpF, ndhA, ndhB, petB, rpl16, rpl2, rpoC1, rps16, trnK-UUU, trnG-UCC, trnL-UAA, trnV-UAC, trnI-GAU, and trnA-UGC, have one intron. Three genes, namely clpP, rps12 and ycf3, have two introns (Table 3). Notably, the rps12, which has three exons, the exon at the 5′ end appears in the LSC region and the other two exons at the 3′ end are in the IRa and IRb regions. The anti-splicing feature of this rps12 gene in the chloroplast genome appears to be extremely common in the chloroplast of terrestrial plants (Tadini et al. 2018).

Table 3.

Break up genes in the chloroplast of W. villosa and the lengths of their introns

| Gene | Location | Exon I (bp) | Intron I (bp) | Exon II (bp) | Intron II (bp) | Exon III (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| atpF | LSC | 410 | 798 | 148 | – | – |

| clpP | LSC | 255 | 635 | 294 | 846 | 69 |

| ndhA | SSC | 538 | 1051 | 557 | – | – |

| ndhB | IR | 777 | 702 | 756 | – | – |

| petB | LSC | 6 | 1042 | 642 | – | – |

| rpl16 | LSC | 402 | 1047 | 9 | – | – |

| rpl2 | IR | 430 | 661 | 389 | – | – |

| rpoC1 | LSC | 1638 | 712 | 432 | – | – |

| rps12 | LSC-IRs | 113 | – | 230 | 552 | 26 |

| rps16 | LSC | 218 | 743 | 40 | – | – |

| trnK-UUU | LSC | 14 | 2683 | 36 | ||

| trnG-UCC | LSC | 22 | 703 | 47 | ||

| trnL-UAA | LSC | 34 | 533 | 49 | ||

| trnV-UAC | LSC | 36 | 604 | 35 | ||

| trnI-GAU | IR | 36 | 941 | 34 | ||

| trnA-UGC | IR | 34 | 802 | 34 | ||

| ycf3 | LSC | 155 | 781 | 228 | 716 | 127 |

Codon usage and RNA editing sites

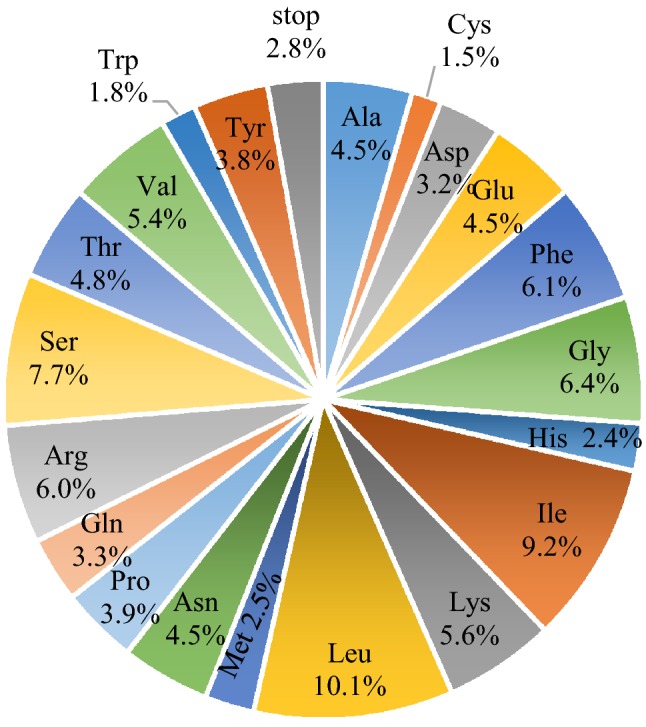

All 87 protein-coding genes are encoded by 64 different codons, among which three are stop codons (TAA, TAG, TGA, Table 4). Moreover, the amino acids Leucine (Leu, 10.1%) and Cysteine (Cys, 1.5%) are found in the largest and the smallest proportion among the 20 amino acids, respectively (Fig. 2). As shown in Table 4, the frequency of the codon ATT encoding isoleucine is the highest, while that of the codon CGC encoding arginine is the lowest. The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU), whose value represents the ratio between the usage frequency and expected frequency of a particular codon (Rodriguez et al. 2018), was introduced to evaluate the codon usage of the W. villosa plastome. As shown in Table 4, the RSCU value of A/T at the third digit of the codon is significantly higher than that of G/C. It is common that the third position of the codon is predominantly A/T, which is positively correlated with the frequency of A and T in most chloroplast genomes of terrestrial plants (Tian et al. 2018). The start codon (ATG) and Tryptophan (Trp), encoded by codon (TGC), exhibits a pattern similar to that observed in the other two recorded Amomum species (Wu et al. 2017, 2018), A. compactum and A. krevanh, for which complete chloroplast sequences are available.

Table 4.

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) for protein-coding genes in the plastome of W. villosa

| Codon | Amino acid A | Frequency | RSCU | Codon | Amino acid A | Frequency | RSCU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCT | A (Ala) | 544 | 1.78 | CCA | P (Pro) | 331 | 1.24 |

| GCC | A (Ala) | 183 | 0.60 | CCC | P (Pro) | 209 | 0.78 |

| GCA | A (Ala) | 379 | 1.24 | CCG | P (Pro) | 134 | 0.50 |

| GCG | A (Ala) | 115 | 0.38 | CCT | P (Pro) | 392 | 1.47 |

| TGT | C (Cys) | 288 | 1.42 | CAA | Q (Gln) | 663 | 1.46 |

| TGC | C (Cys) | 118 | 0.58 | CAG | Q (Gln) | 245 | 0.54 |

| GAT | D (Asp) | 683 | 1.57 | CGT | R (Arg) | 273 | 1.01 |

| GAC | D (Asp) | 187 | 0.43 | CGC | R (Arg) | 81 | 0.30 |

| GAA | E (Glu) | 920 | 1.52 | CGA | R (Arg) | 326 | 1.20 |

| GAG | E (Glu) | 293 | 0.48 | CGG | R (Arg) | 125 | 0.46 |

| TTT | F (Phe) | 1029 | 1.25 | AGA | R (Arg) | 600 | 2.21 |

| TTC | F (Phe) | 623 | 0.75 | AGG | R (Arg) | 221 | 0.82 |

| GGT | G (Gly) | 580 | 1.33 | TCT | S (Ser) | 534 | 1.52 |

| GGC | G (Gly) | 159 | 0.36 | TCC | S (Ser) | 331 | 0.94 |

| GGA | G (Gly) | 708 | 1.62 | TCA | S (Ser) | 431 | 1.23 |

| GGG | G (Gly) | 300 | 0.69 | TCG | S (Ser) | 234 | 0.67 |

| CAT | H (His) | 473 | 1.43 | AGT | S (Ser) | 412 | 1.18 |

| CAC | H (His) | 187 | 0.57 | AGC | S (Ser) | 160 | 0.46 |

| ATT | I (Ile) | 1120 | 1.35 | ACT | T (Thr) | 481 | 1.48 |

| ATC | I (Ile) | 601 | 0.72 | ACC | T (Thr) | 240 | 0.74 |

| ATA | I (Ile) | 773 | 0.93 | ACA | T (Thr) | 428 | 1.32 |

| AAA | K (Lys) | 1083 | 1.42 | ACG | T (Thr) | 152 | 0.47 |

| AAG | K (Lys) | 445 | 0.58 | GTT | V (Val) | 509 | 1.38 |

| TTA | L (Leu) | 798 | 1.75 | GTC | V (Val) | 188 | 0.51 |

| TTG | L (Leu) | 560 | 1.23 | GTA | V (Val) | 563 | 1.53 |

| CTT | L (Leu) | 531 | 1.16 | GTG | V (Val) | 214 | 0.58 |

| CTC | L (Leu) | 238 | 0.52 | TGG | W (Trp) | 475 | 1.00 |

| CTA | L (Leu) | 416 | 0.91 | TAT | Y (Tyr) | 771 | 1.49 |

| CTG | L (Leu) | 194 | 0.43 | TAC | Y (Tyr) | 267 | 0.51 |

| ATG | M (Met) | 676 | 1.00 | TAA | * | 269 | 1.06 |

| AAT | N (Asn) | 873 | 1.44 | TAG | * | 207 | 0.81 |

| AAC | N (Asn) | 339 | 0.56 | TGA | * | 287 | 1.13 |

*, stop codon

Fig. 2.

Composition of 20 amino acid and stop codons for protein-coding genes in the chloroplast genome of W. villosa

In addition, a total of 59 putative RNA editing sites in 35 genes were identified and summarized (see Table S1). Uniquely, all the nucleotide codon changes found are Cytidine (C)—Thymine (T) editing, which normally occurs in the transcript of terrestrial plant chloroplast genomes (Tsudzuki et al. 2001). The amino acid conversion from Leucine (L) to Serine (S) was the predominant occurrence (30), accounting for over half of all editing sites. Moreover, two genes were found to use AUG substitutes as the start codon, including ndhD (ATC) and rpl2 (ATA).

Sequence repeats analysis

Simple sequence repeats (SSRs), also known as microsatellite sequences (MS) or short tandem repeats (STR), are commonly used for genetic analyses comparing multiple species due to their rich polymorphisms, co-dominance, high repeatability, and reliability. Previous studies have used SSRs for plant gene mapping, kinship, and genetic diversity studies, as well as molecular marker-assisted breeding (Huang et al. 2014a, b; Zhao et al. 2014). Our repeat analysis revealed a total of 392 SSRs loci. Among these SSRs, mononucleotides, dinucleotides, trinucleotides, and other nucleotides account for 47.4%, 21.2%, 25.5%, and 5.9%, respectively (Table 5). It is noteworthy that these SSRs are generally composed of adenine (A) or thymine (T) repeats, which is consistent with other Zingiberaceae species. This illustrates that chloroplast SSRs generally consist of short repeats of poly A/T (Ni et al. 2016). These results provide a good resource for SSR makers for the study of genetic diversity and species identification between W. villosa and related species.

Table 5.

Analysis of simple sequence repeats in the W. villosa chloroplast genome

| SSR type | Repeat unit | Amount | Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mono | A/T | 180 | 96.8 |

| C/G | 6 | 3.2 | |

| Di | AC/GT | 2 | 2.4 |

| AG/CT | 20 | 24.1 | |

| AT/AT | 61 | 73.5 | |

| Tri | AAC/GTT | 12 | 12 |

| AAG/CTT | 28 | 28 | |

| AAT/ATT | 36 | 36 | |

| ACT/AGT | 2 | 2 | |

| AGC/CTG | 7 | 7 | |

| AGG/CCT | 8 | 8 | |

| ATC/ATG | 7 | 7 | |

| Tetra | AAAC/GTTT | 1 | 6.25 |

| AAAG/CTTT | 3 | 18.75 | |

| AAAT/ATTT | 6 | 37.5 | |

| AACT/AGTT | 1 | 6.25 | |

| AATG/ATTC | 2 | 12.5 | |

| AATT/AATT | 2 | 12.5 | |

| ACAT/ATGT | 1 | 6.25 | |

| Penta | AAAAT/ATTTT | 2 | 40 |

| AAATC/ATTTG | 1 | 20 | |

| AAATT/AATTT | 1 | 20 | |

| AATAT/ATATT | 1 | 20 | |

| Hexa | ACTATC/AGTGAT | 2 | 100 |

| Total | 392 |

In addition to SSRs, long sequence repeats including forward repeats and palindromes are compared and summarized in Table 6. In the whole W. villosa chloroplast genome, a total of 12 forward and 16 palindrome repeats were detected by the REPuter program. Among these long repeats, the vast majority of repeats are located in intronic and intergenic spacer regions, while a few are located in protein-coding regions. Six pairs of repeats are associated with five tRNA genes (trnS-GGA, trnG-UCC, trnG-GCC, trnL-UAA, trnI-CAT). The gene richest in repeats is ycf2, carrying two forward and two palindrome repeats, which is similar with other chloroplast genomes (Bendich 2004).

Table 6.

Analysis of long sequence repeats in the W. villosa chloroplast genome

| ID | Repeat start 1 | Type | Size (bp) | Repeat start 2 | Mismatch (bp) | E-value | Gene | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1322 | F | 34 | 1335 | − 1 | 2.60E−09 | IGS | LSC |

| 2 | 5299 | P | 31 | 129065 | − 3 | 1.98E−04 | rps16 (intron); ndhA (intron) | LSC; SSC |

| 3 | 8832 | P | 31 | 48088 | − 3 | 1.98E−04 | IGS; trnS-GGA | LSC |

| 4 | 9082 | P | 36 | 9082 | − 2 | 9.04E−09 | IGS | LSC |

| 5 | 10064 | P | 33 | 10064 | − 3 | 1.50E−05 | trnG-UCC (intron) | LSC |

| 6 | 10617 | F | 30 | 39372 | − 3 | 7.16E−04 | trnG-UCC; trnG-GCC | LSC |

| 7 | 13368 | P | 35 | 13368 | − 3 | 1.13E−06 | atpF (intron) | LSC |

| 8 | 20114 | P | 46 | 20114 | 0 | 1.52E−18 | rpoC2 | LSC |

| 9 | 39472 | P | 32 | 39472 | 0 | 4.08E−10 | IGS | LSC |

| 10 | 41585 | F | 53 | 43809 | − 3 | 5.87E−17 | psaB; psaA | LSC |

| 11 | 41624 | F | 37 | 43848 | − 2 | 2.39E−09 | psaB; psaA | LSC |

| 12 | 50102 | P | 30 | 63517 | − 3 | 7.16E−04 | IGS | LSC |

| 13 | 50698 | P | 31 | 50698 | − 3 | 1.98E−04 | trnL-UAA (intron) | LSC |

| 14 | 54252 | F | 30 | 69399 | − 3 | 7.16E−04 | IGS | LSC |

| 15 | 71780 | F | 30 | 71807 | 0 | 6.53E−09 | IGS | LSC |

| 16 | 72413 | F | 42 | 72434 | − 3 | 1.21E−10 | rps18 | LSC |

| 17 | 91396 | F | 46 | 91446 | − 1 | 2.10E−16 | trnI-CAT; IGS | IRb |

| 18 | 91396 | P | 46 | 160796 | − 1 | 2.10E−16 | trnI-CAT; IGS | IRb/IRa |

| 19 | 91446 | P | 46 | 160846 | − 1 | 2.10E−16 | IGS | IRb/IRa |

| 20 | 94064 | F | 30 | 94085 | − 3 | 7.16E−04 | ycf2 | IRb |

| 21 | 94064 | P | 30 | 158173 | − 3 | 7.16E−04 | ycf2 | IRb/IRa |

| 22 | 94085 | P | 30 | 158194 | − 3 | 7.16E−04 | ycf2 | IRb/IRa |

| 23 | 121872 | P | 30 | 121927 | − 3 | 7.16E−04 | IGS | SSC |

| 24 | 121876 | P | 56 | 121876 | 0 | 1.45E−24 | IGS | SSC |

| 25 | 123198 | P | 30 | 123198 | − 2 | 2.56E−05 | ccsA | SSC |

| 26 | 158175 | F | 30 | 158196 | − 3 | 7.16E−04 | ycf2 | IRa |

| 27 | 160796 | F | 46 | 160846 | − 1 | 2.10E−16 | IGS | IRa |

| 28 | 160815 | F | 30 | 160865 | − 3 | 7.16E−04 | IGS | IRa |

F forward; P palindrome; IGS intergenic spacer region

IR contraction and expansion

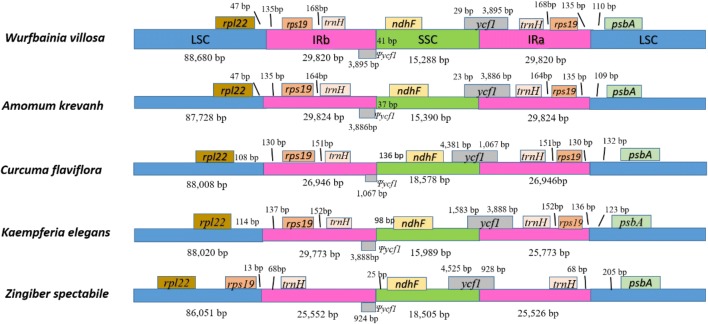

As mentioned above, the typical quadripartite structure of the chloroplast genome includes two different single-copy regions and two inverted repeat regions. In the chloroplast genome, the IR regions are the most conserved, while the contraction and expansion of IRs are usually considered evolutionary events and are used to study structural differences among chloroplast genomes (Kim and Lee 2004). In this study, the plastome of W. villosa was compared with four other Zingiberaceae species to obtain an overall picture of their key structures. As illustrated in Fig. 3, all examined chloroplast genomes generally have rps19-trnH clusters in IRa and IRb regions. The boundaries of LSC-IRb are located in the left side of the rps19 genes. These characters have been found in most monocots (Wang et al. 2008). However, Zingiber spectabile is an exception because its IR-LSC junction is located upstream of the trnH gene and the rps19 gene is situated in the LSC region. This might be due to the contraction of the IR regions, which results in a shorter complete chloroplast genome in this species than in other Zingiberaceae species. The distances between the photosynthetic gene ndhF and the IRb/SSC boundary is 41 bp, 37 bp, 136 bp, 98 bp, and 33 bp in W. villosavillosa, A. krevanh, C. flaviflora, K. elegans, and Z. spectabile, respectively. ycf1 spans across the IRa-SSC junction, producing a deletion of the 5′ end of the pseudogene in the IRb region. Because of this, the ycf1 region can serve as a potential region for candidate barcode screening for species identification within the Zingiberaceae family (Dong et al. 2015).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of LSC, IR and SSC border among the complete chloroplast genomes W. villosa and four other Zingiberaceae species. The distance between the ends of the genes and the boundaries was represented by lengths in bp shown above the image. Ψ stands for pseudogene

Genome comparison analysis

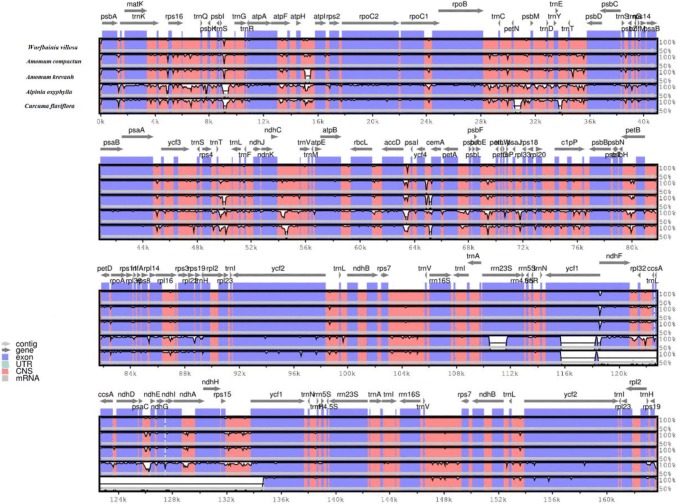

Comparative analyses among DNA sequences has increasingly become one of the most practical approaches for identifying functional and important genomic regions. The mVISTA tool was designed for aligning DNA sequences, quickly visualizing the level of protection between/among them, and identifying highly conserved regions (Dubchak and Ryaboy 2006; Ratnere and Dubchak 2009). Here, a comparative analysis of the W. villosa chloroplast genome with that of four reported Zingiberaceae species was performed using the mVISTA program. As shown in Fig. 4, the whole chloroplast genome sequences are slightly different among three Amomum species. Other species within Zingiberaceae (Alpinia oxyphylla and Curcuma flaviflora) are quite different, especially in the LSC and SSC regions. These differences are mainly located in the intergenic spacers. Divergence also has occurred in several genes, such as rrn23s, ycf1, matK, ndhF, and ndhD. Overall, the results showed that the coding region is more conservative than the non-coding region. These differential sequences identified in the chloroplast genomes provide potential regions for species identification.

Fig. 4.

Sequence comparison of the chloroplast genomes of W. villosa and four Zingiberaceae species using the mVISTA program. Gray arrows indicate the position and orientation of genes; purple bars represent exons; pink bars represent non-coding sequences. The scales on the Y axis represent percentage identity ranging from 50 to 100%

Phylogenetic analyses

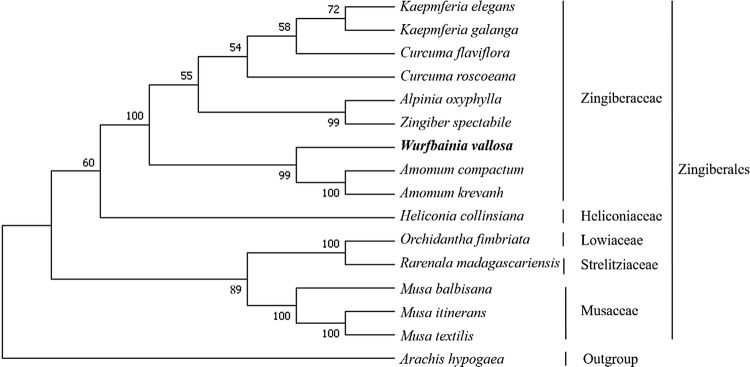

Phylogenetic trees are commonly used for systematic analyses to obtain a better understanding of the evolutionary history of organisms. To evaluate the taxonomic relationships of W. villosa and other related species, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis on 14 Zingiberales species and one outgroup (Arachis hypogaea; Fabales) (Table S2). The results of the phylogenetic analysis showed that W. villosa shares a most recent common ancestor with the sister species Amomum krevanh and Amomum compactum with strong bootstrap values of 99%. This W. villosa clade is most closely related to the other included Zingiberaceae species (Fig. 5). This phylogenetic relationship is consistent with that of a previous report (Reginato et al. 2016). However, the phylogenetic relationships among this family require further investigation because of the limited availability of the whole chloroplast genome sequences of the Zingiberaceae. Therefore, in order to further study the evolutionary history of W. villosa, more whole chloroplast sequences of Zingiberaceae species are required.

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic relationships based on the complete chloroplast genomes of 15 species in Zingiberales and one outgroup species (Fabales). The numbers on the nodes are the bootstrap support

Materials and methods

Plant materials and DNA extraction

Fresh leaves of Wurfbainia villosa were collected from the Medicinal Botanical Garden in Guangdong Province, China. Total genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 50 mg fresh leaves of W. villosa, using a modified CTAB method. Then, the DNA concentration of each sample was checked by a Nanodrop-2000 spectrometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). We focus not only on the DNA concentration but also on the ratio of OD value of the sample at 260 nm and 280 nm/230 nm to test the nucleic acid purity. Additionally, agarose gel electrophoresis was used to assess the quality of DNA.

Sequencing, assembly, and annotation

Illumina HiSeq 2000 Sequencing generated 5.15 GB data in total, among which 14,538,499 paired-end clean reads were retained after filtering and trimming the low-quality reads using Trimmomatic (v0.36, Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology, Potsdam, Germany). The sequencing coverage of the chloroplast genome is 100%, and bowtie2 and samtools were used to obtain the sequencing depth, which was up to 413 × . The complete sequences of A. compactum and A. kravanh chloroplast genome were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and served as the references. Based on coverage and similarity, chloroplast-like reads were extracted from the clean reads and assembled using the Abyss2.0 program to generate a complete chloroplast genome sequence. BLASTn was used to conduct self-alignment to locate the precise position of the quadripartite structure. In order to verify the assembly, four regions between the IR regions and the LSC/SSC region were confirmed through PCR amplification which was about 500 bp long and Sanger sequencing (Sangon Biotech). The primers designed with Primer premier 5 software were shown in Table S3. PCR conducted using the PrimeSTAR Max (Takara, Japan) and the CFX96 Touch Deep Well platform (Bio-Rad, America) with a total reaction volume of 50 µL, including 4 µL of the cDNA, 25 µL of the PrimeSTAR Max, 2 µL of the 10 µM primers and 17 µL of the nuclease free water. The PCR procedure was as follows: 98 °C for 2 min; 98 °C for 10 s; 56 °C for 15 s; 72 °C for 15 s and 72 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles. The electrophoresis results in Figure S1 showed that the amplification length was about 500 bp, which is consistent with the expected length.

Preliminarily gene annotation of the W. villosa chloroplast genome was performed by the CPGAVAS online tool (http://www.herbalgenomics.org/cpgavas) and the annotation information was further examined and revised manually with the assistance of the CLC Sequence Viewer (version 8). The Organellar Genome DRAW (OGDRAW) (v1.2, Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology, Potsdam, Germany) was used to draw a detailed physical map of the W. villosa chloroplast genome. Finally, the complete chloroplast of the W. villosa genome was deposited into NCBI GenBank with the accession number MK606408.

Sequence analyses and genome comparison

After annotation, the map of the whole chloroplast genome was drawn with the OGDRAW program (https://chlorobox.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/index.html). The distribution of codon usage along with the GC content of the W. villosa chloroplast genome was analyzed using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA, version 7) (Kumar et al. 2016). MISA (Hennequin et al. 2001) software was used to detect the SSR loci. REPuter (Kurtz et al. 2001) (https://bibiserv2.cebitec.uni-Bielefeld.de/reputer) was used to identify long sequence repeats with the Hamming distance set at three and the minimum repeat length set at 30 bp. All putative duplicates were verified and duplicate results were manually deleted. Additionally, the online program Predictive RNA Editor for Plants (PREP) was used to predict RNA editing sites, with a cut-off value of 0.8. The mVISTA tool (http://genome.lbl.gov/vista/index.shtml) was used for whole-genome alignment analysis of the W. villosa chloroplast genome and four other Zingiberaceae species in the Shuffle-LAGAN mode (Frazer et al. 2004).

Phylogenetic analysis

A phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the whole chloroplast genome sequence of W. villosa and 14 species in Zingiberales (Curcuma flaviflora, NC_028729.1; Alpinia oxyphylla, NC_035895.1; Amomum krevanh, NC_036935.1; Amomum compactum, NC_036992.1; Kaempferia elegans, NC_040852.1; Kaempferia galangal, NC_040851.1; Curcuma roscoeana, NC_022928.1; Zingiber spectabile, NC_036992.1; Musa itinerans, NC_035723.1; Musa balbisiana, NC_028439.1; Musa textilis, NC_022926.1; Rarenala madagascariensis, NC_022927.1; Heliconia collinsiana, NC_020362.1; Orchidantha fimbriata, KF_601569.1); the outgroup for the analysis was Arachis hypogaea (Fabales) (NC_037358.1). These complete chloroplast genome sequences were downloaded from the NCBI Organelle Genome Resources database (Table S2) and trimmed manually to remove the IRa region. Then, their sequences was further aligned by the Multiple Alignment using Fast Fourier Transform (MAFFT) program (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Toolsmsa/mafft/). MEGA 6.06 was used to construct phylogenetic analyses with Maximum Likelihood (ML) and the GTR + G substitution model, which was selected based on model screening. The bootstrap analysis was executed with 1000 replicates and TBR branch swapping, which can represent the correlation between the different species, thereby providing an estimation of the reliability of a cluster analysis.

Conclusions

Compared with the nuclear genome, the chloroplast genome is much smaller and is maternally inherited. Due to its high conservation in gene content, gene sequence, base composition, and low frequency of nucleotide substitution, the chloroplast genome is essential for studying the development of species system. In this study, the complete chloroplast genome of Wurfbainia villosa was presented as a circular molecule of 163,608 bp in length, with a typical quadripartite structure. By comparing the complete chloroplast sequence with related species, it was found that the chloroplast genome size of related species was affected by IR contraction. Furthermore, the chloroplast genome of W. villosa exhibits high structural conservation on the basis of sequence characteristics and it is closely related to other reported Amomum species. Importantly, the complete chloroplast genome of W. villosa provides abundant information for phylogenetic, population, and evolutionary studies of this species, contributing to a deeper comprehension of the phylogenetics and chloroplast biology among the Zingiberaceae.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wenli An and Jing Li have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Song Huang, Email: hsl318@gzucm.edu.cn.

Xiasheng Zheng, Email: xszheng@gzucm.edu.cn.

References

- Barbosa GB, Jayasinghe NS, Natera SHA, Inutan ED, Peteros NP, Roessner U. From common to rare Zingiberaceae plants—a metabolomics study using GC–MS. Phytochemistry. 2017;140:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendich AJ. Circular chloroplast chromosomes: the grand illusion. Plant Cell. 2004;16(7):1661–1666. doi: 10.1105/tpc.160771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Ding P, Xu X, Xu H. A resource investigation and commodity identification of Fructus Amomi. J Chin Med Mater. 2001;24(1):18–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SL, Sun C, Song JY, Xu J, et al. Herbgenomics. Beijing: China Science Publishing & Media Ltd.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg MT, Gaut BS, Learn GH, Morton BR. Rates and patterns of chloroplast DNA evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(15):6795–6801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao WR, Zhang LL, Feng SS, Xu JG. Chemical composition, antibacterial activity, and mechanism of action of the essential oil from Amomum kravanh. J Food Prot. 2014;77(10):1740–1746. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W, Xu C, Li C, Sun J, Zuo Y, Shi S, Cheng T, Guo J, Zhou S. ycf1, the most promising plastid DNA barcode of land plants. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8348. doi: 10.1038/srep08348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W, Xu C, Li W, Xie X, Lu Y, Liu Y, Jin X, Suo Z. Phylogenetic resolution in juglans based on complete chloroplast genomes and nuclear DNA sequences. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1148. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubchak I, Ryaboy DV. VISTA family of computational tools for comparative analysis of DNA sequences and whole genomes. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;338:69–89. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-097-9:69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyall SD, Brown MT, Johnson PJ. Ancient invasions: from endosymbionts to organelles. Science. 2004;304(5668):253–257. doi: 10.1126/science.1094884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimzadeh Attari V, Malek Mahdavi A, Javadivala Z, Mahluji S, Zununi Vahed S, Ostadrahimi A. A systematic review of the anti-obesity and weight lowering effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) and its mechanisms of action. Phytother Res. 2018;32(4):577–585. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W273–W279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennequin C, Thierry A, Richard GF, Lecointre G, Nguyen HV, Gaillardin C, Dujon B. Microsatellite typing as a new tool for identification of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(2):551–559. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.2.551-559.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Shi C, Liu Y, Mao SY, Gao LZ. Thirteen Camellia chloroplast genome sequences determined by high-throughput sequencing: genome structure and phylogenetic relationships. BMC Evol Biol. 2014;14:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Duan Z, Yang J, Ma X, Zhan R, Xu H, Chen W. SNP typing for germplasm identification of Amomum villosum L. based on DNA barcoding markers. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e114940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstin D, Trevor RH, Evelyn F, Susanne B. An optimized chloroplast DNA extraction protocol for grasses (Poaceae) proves suitable for whole plastid genome sequencing and SNP detection. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(7):e2350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Lee HL. Complete chloroplast genome sequences from Korean ginseng (Panax schinseng Nees) and comparative analysis of sequence evolution among 17 vascular plants. DNA Res. 2004;11(4):247–261. doi: 10.1093/dnares/11.4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(22):4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni L, Zhao Z, Xu H, Chen S, Dorje G. The complete chloroplast genome of Gentiana straminea (Gentianaceae), an endemic species to the Sino-Himalayan subregion. Gene. 2016;577(2):281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnere I, Dubchak I. Obtaining comparative genomic data with the VISTA family of computational tools. Curr Prot Bioinform. 2009;10:10–16. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1006s26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reginato M, Neubig KM, Majure LC, Michelangeli FA. The first complete plastid genomes of Melastomataceae are highly structurally conserved. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2715. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Wright G, Emrich S, Clark PL. %MinMax: a versatile tool for calculating and comparing synonymous codon usage and its impact on protein folding. Protein Sci. 2018;27(1):356–362. doi: 10.1002/pro.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi-Rad M, Varoni EM, Salehi B, Sharifi-Rad J, Matthews KR, Ayatollahi SA, Kobarfard F, Ibrahim SA, Mnayer D, Zakaria ZA, et al. Plants of the genus zingiber as a source of bioactive phytochemicals: from tradition to pharmacy. Molecules. 2017;22(12):2145. doi: 10.3390/molecules22122145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Wu M, Liao B, Liu Z, Bai R, Xiao S, Li X, Zhang B, Xu J, Chen S. Complete chloroplast genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the medicinal plant Artemisia annua. Molecules. 2017;22(8):1330. doi: 10.3390/molecules22081330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudianto E, Wu CS, Leonhard L, Martin WF, Chaw SM. Enlarged and highly repetitive plastome of Lagarostrobos and plastid phylogenomics of Podocarpaceae. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2019;133:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadini L, Ferrari R, Lehniger MK, Mizzotti C, Moratti F, Resentini F, Colombo M, Costa A, Masiero S, Pesaresi P. Trans-splicing of plastid rps12 transcripts, mediated by AtPPR4, is essential for embryo patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2018;248(1):257–265. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-2896-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri S, Abdullah TL, Rafii MY, Harikrishna JA, Werbrouck SPO, Teo CH, Sahebi M, Azizi P. De novo assembly of transcriptomes, mining, and development of novel EST-SSR markers in Curcuma alismatifolia (Zingiberaceae family) through Illumina sequencing. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):3047. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39944-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian YQ, Ding P, Yan XH, Hu WJ. Discussion on quality control of preparations with cortex moutan in volume I pharmacopoeia of People’s Republic of China (2005 edition) Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2008;33(3):339–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian N, Han L, Chen C, Wang Z. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Epipremnum aureum and its comparative analysis among eight Araceae species. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0192956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsudzuki T, Wakasugi T, Sugiura M. Comparative analysis of RNA editing sites in higher plant chloroplasts. J Mol Evol. 2001;53(4–5):327–332. doi: 10.1007/s002390010222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veleba A, Smarda P, Zedek F, Horova L, Smerda J, Bures P. Evolution of genome size and genomic GC content in carnivorous holokinetics (Droseraceae) Ann Bot. 2017;119(3):409–416. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcw229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RJ, Cheng CL, Chang CC, Wu CL, Su TM, Chaw SM. Dynamics and evolution of the inverted repeat-large single copy junctions in the chloroplast genomes of monocots. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, de Pamphilis CW, Muller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;76(3–5):273–297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Li Q, Hu Z, Li X, Chen S. The complete Amomum kravanh chloroplast genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the commelinids. Molecules. 2017;22(11):1875. doi: 10.3390/molecules22111875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ML, Li Q, Xu J, Li XW. Complete chloroplast genome of the medicinal plant Amomum compactum: gene organization, comparative analysis, and phylogenetic relationships within Zingiberales. Chin Med. 2018;13:10. doi: 10.1186/s13020-018-0164-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yukawa M, Tsudzuki T, Sugiura M. The chloroplast genome of Nicotiana sylvestris and Nicotiana tomentosiformis: complete sequencing confirms that the Nicotiana sylvestris progenitor is the maternal genome donor of Nicotiana tabacum. Mol Genet Genom. 2006;275(4):367–373. doi: 10.1007/s00438-005-0092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Yin J, Guo H, Zhang Y, Xiao W, Sun C, Wu J, Qu X, Yu J, Wang X, et al. The complete chloroplast genome provides insight into the evolution and polymorphism of Panax ginseng. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:696. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Shen J, Wang Z. Identification of Amomum villosum and Jian Amomum villosum. Strait Pharm J. 2017;29(09):15–18. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.