Abstract

COX-2 has been inappropriately overexpressed in various human malignancies, and is considered as one of the representative targets for the chemoprevention of inflammation-associated cancer. In order to assess the role of COX-2 in colitis-induced carcinogenesis, the selective COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib and COX-2 null mice were exploited in an azoxymethane (AOM)-initiated and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-promoted murine colon carcinogenesis model. The administration of 2% DSS in drinking water for 1 week after a single intraperitoneal injection of AOM produced colorectal adenomas in 83% of mice, whereas only 27% of mice given AOM alone developed tumors. Oral administration of celecoxib significantly lowered the incidence as well as the multiplicity of colon tumors. The expression of COX-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) was upregulated in the colon tissues of mice treated with AOM and DSS, and this was inhibited by celecoxib administration. Likewise, celecoxib treatment abrogated the DNA binding of NF-κB, a key transcription factor responsible for regulating expression of aforementioned pro-inflammatory enzymes, which was associated with suppression of IκBα degradation. In the COX-2 null (COX-2–/–) mice, there was about 30% reduction in the incidence of colon tumors, and the tumor multiplicity was also markedly reduced (7.7 ± 2.5 vs. 2.43 ± 1.4, P < 0.01). As both pharmacologic inhibition and genetic ablation of COX-2 gene could not completely suppress colon tumor formation following treatment with AOM and DSS, it is speculated that other pro-inflammatory mediators, including COX-1 and iNOS, should be additionally targeted to prevent inflammation-associated colon carcinogenesis.

Keywords: Chemoprevention, Celecoxib, Colitis, Colon cancer, COX-2

INTRODUCTION

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) face an increased lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC). Although early detection and appropriate removal of polyps represent essential components for the prevention of sporadic CRC, intervention with an efficient anti-inflammatory strategy may provide the better opportunity in the management of the colitis-associated cancer [1-3].

While normal colonic mucosa does not express COX-2, this enzyme is abnormally upregulated during the colorectal carcinogenesis in an ‘adenoma-carcinoma’ or an ‘inflammation-dysplasia-carcinoma’ sequence [4]. As aberrant COX-2 overexpression accelerates carcinogenesis by stimulating cell proliferation and rendering cancerous cells resistant to apoptosis, COX-2 inhibition has been considered to be a rational strategy for the chemoprevention of CRC. In line with this notion, offsprings from COX-2 null mice mated to ApcΔ716 mutant mice exhibited an 86% reduction in the number of polyps compared to those from the ApcΔ716 control littermates [5]. Further data from epidemiologic, animal, and clinical studies indicate that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with COX-2 inhibitory activities are capable of preventing intestinal polyposis or CRC [6,7].

However, other studies have revealed that COX-2 may have a negligible or even an opposite effect on colon inflammation and possibly, carcinogenesis. Both myeloid cell- and endothelial cell-specific COX-2 knockout mice exhibited an increase in experimentally induced colitis and decreased epithelial cell proliferation when compared with control littermates [8]. Thus, COX-2 expression in myeloid cells and endothelial cells may play a role in protecting epithelial cells in this murine colitis model. Moreover, pharmacologic inhibition of the COX-2 function exacerbates symptoms in patients with colitis [9] and in rats [10]. Notably, the disruption of COX-1 (Ptgs1) in the mouse attenuated gastrointestinal abnormalities, whereas COX-2 (Ptgs2) null mice showed reproductive anomalies and defects in kidney development [11,12]. These findings suggest that the current COX-2 targeted strategy for the purpose of cancer prevention is not necessarily valid and may need to be reconsidered. With regards to the controversy on the role of COX-2 in colorectal carcinogenesis, Ishikawa and Herschman [13] concluded that the mechanism underlying colitis-associated colon cancer formation in mice might differ from that for hereditary and sporadic CRCs in humans, suggesting the possible involvement COX-2-independent mechanisms.

In the current study, we attempted to evaluate the chemopreventive effects of pharmacological inhibition and genetic ablation of COX-2 in the azoxymethane (AOM)-initiated and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-promoted intestinal tumorigenesis in mice, an experimental model that mimics the human colitis-associated CRC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and reagents

Male Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice (Daehan Biolink Experimental Animal Center, Daejeon, Korea) five to six week of age and the COX-2+/+ and COX-2–/– mice of C57BL/6J3129/Ola genetic background [11,12,14] were maintained at the Animal Facility of Seoul National University according to the Institutional Animal Care guidelines. All animal experiments were conducted on protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Seoul National University (SNU-060616-2). After the adaptation for 7 days, the mice were randomly assigned to treatment and control groups. All animals were housed in plastic cages (four mice/cage) with free access to drinking water and a pelleted basal diet, CRF-1 (Purina Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), under climate-controlled quarters (24°C at 50% humidity) with a 12-hour light-12 hour dark cycle. AOM was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). DSS with a molecular weight of 36 to 50 kDa was obtained from MP Biochemicals, Inc. (Solon, OH, USA) and dissolved in distilled water at a concentration of 2% (w/v). Celecoxib suspended in 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) was given to mice by gastric intubation.

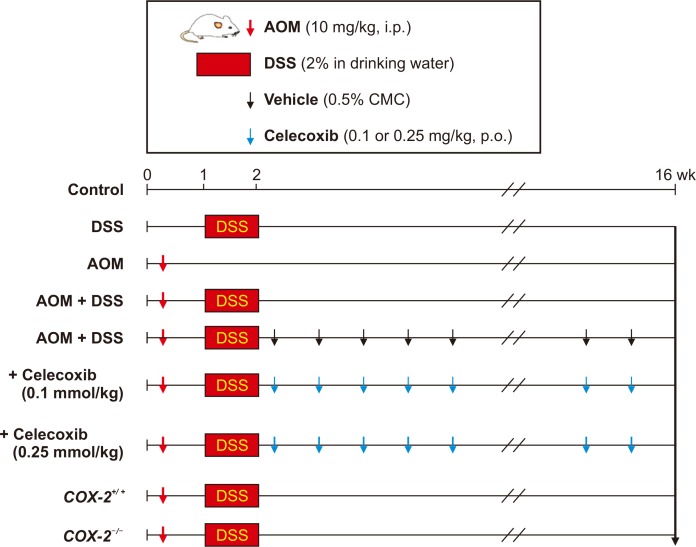

Development of colon tumors in mice

Male ICR mice were divided into 7 groups (Fig. 1) for use in a colitis-associated murine carcinogenesis experiment [15]. Group 1 mice were given a vehicle only, Group 2 mice treated with 2% DSS alone in drinking water for 7 days, Group 3 mice treated with a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) dose (10 mg/kg) of AOM, and Group 4 mice given a single i.p. injection of AOM followed by 2% DSS in the drinking water for 7 days. The remaining three groups were assigned for evaluating the effect of celecoxib treatment; Group 5 same as Group 4 treated additionally with 0.5% CMC alone served as a control group, Group 6 given 0.1 mmole/kg celecoxib orally for 14 weeks, and Group 7 was given 0.25 mmole/kg celecoxib for 14 weeks. To further verify the role of COX-2 in the AOM-initiated and DSS-promoted carcinogenesis [15], we compared the incidence and the multiplicity of AOM plus DSS-induced colon carcinogenesis between COX-2 wild-type and COX-2 knockout mice [11,14]. After 16 weeks, all mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation for further analysis.

Figure 1. Experimental schedule for inducing colitis-induced adenomas in mice.

AOM, azoxymethane; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; i.p., intraperitoneal; p.o., per oral.

Histopathological evaluation

The extracted colon tissue was spread onto a plastic sheet, fixed in 10% formalin for 16 hours, and prepared for paraffin block. The paraffin sections were subjected to the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining to assess the severity of histopathological colitis. Colon cancer cells associated with ulcerative colitis was verified microscopically by a pathologist. The tumor incidence and the multiplicity were calculated by the following formulae; tumor incidence (%) = (number of tumor-bearing mice / total number of mice) × 100 and tumor multiplicity = number of tumors / number of tumor-bearing mice.

Mast cell staining and counting

The paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized with xylene and stained with 0.5% toluidine blue in acetate buffer (pH 4.0). Staining with acidic toluidine blue gave rise to a light blue background, which permitted mapping of the metachoronic mast cells with purplish blue-staining granules in their cytoplasm in relation to the other tissue components within the specimen. To count the mast cells, these sections were examined under a microscope with × 100 or × 400 magnification, and a grid eyepiece (0.0625 mm2) was placed over the cross-sectional area of tissues.

Western blot analysis

The colon tissue was collected, placed immediately in liquid nitrogen and pulverized in a mortar. The pulverized colon tissue was homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton-X 100, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 20 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM Na3VO4 and protease inhibitor cocktail tablet [Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany]). Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 ×g for 20 minutes, and aliquots of supernatant containing 40 mg proteins were boiled in SDS sample loading buffer for 5 minutes before electrophoresis on 12% SDS-PAGE. After transfer to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane, the blots were blocked with 5% fat-free dried milk-PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) buffer for 2 hours at room temperature and then washed in PBST buffer. The membranes were incubated for 12 hours at 4°C with 1 : 1,000 dilutions of primary antibodies for COX-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), COX-2 (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Blots were washed three times with PBST at 5 minutes intervals, incubated in a solution containing 1 : 5,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour and then washed again in PBST for three times. The transferred proteins were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Reverse transcription-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the harvested colon tissue by appropriate treatment using the TRIzol® reagent (Life Technologies, Milan, Italy) and 2 mg of total RNA was reverse transcribed by Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). PCR was performed by using the Primix Ex Taq Kit (Takara, Chiba, Japan) with specific primers. The PCR reaction was preformed at respective thermal cycles of 1 minute at 95°C for denaturation and 1 minute at 72°C for annealing. Amplification products were resolved on 1.2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV light.

Preparation of nuclear extracts

For the preparation of nuclear and cytosolic extracts from mouse colon, the tissue was collected, placed immediately in liquid nitrogen and pulverized in a mortar. The pulverized colon tissue was homogenized in ice-cold hypotonic buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH7.8], 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]). After 20 minutes incubation on ice, the nuclear fraction was separated from the cytosolic fraction by centrifugation for 5 minutes at 12,000 ×g. The collected nuclei were washed once with 400 µL of buffer A plus 25 µL of 10% NP-40, centrifuged for 2 minutes at 12,000 ×g, and then resuspended in 150 µL of buffer C (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 50 mM KCl, 300 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF and 10% glycerol). The supernatant containing nuclear proteins was collected by centrifugation for 15 minutes at 12,000 ×g and stored at –80°C after determination of protein concentrations.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay was performed using a DNA-protein binding detection kit (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the NF-κB oligonucleotide probe (5’-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3’) was labeled with [γ-32P] ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase and purified on a Nick column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The binding reaction was carried out in a total volume of 25 µL containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 4% (v/v) glycerol, 0.1 mg/mL sonicated salmon sperm DNA, 10 µg of nuclear extracts, and 100,000 cpm of the labeled probe. After 50 minutes incubation at room temperature, 2 µL of 0.1% bromophenol blue was added, and samples were electrophoresed through a 6% non-denaturating PAGE at 150 V in a cold room for 2 hours. Finally, the gel was dried and exposed to an X-ray film.

Gelatin zymography

Gelatin gels (7.5%) were prepared according to the standard procedure. For preparing the running gel, gelatin stock solution (20 mg/mL in double-distilled H2O) was diluted to get the concentration of 0.2%. For this procedure, the Bio Rad Mini Protean II electrophoresis apparatus was used. During gel solidification, colon tissue protein samples (typically 10-25 µg) were mixed with Tris-glycine SDS sample buffer (2 × 0.5 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], glycerol, 10% SDS and 0.1% bromophenol blue in diluted with deionized water) and then stand for 10 minutes at room temperature. Colon tissue samples were added to wells and then electrophoresed in 1 × Tris-glycine SDS running buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 1.23 M glycine and 0.5% SDS) according to the standard running conditions. After running, the zymogram renaturing buffer (10 × 25% Triton X-100 in double distilled water] was diluted with deionized water (1 : 9, v/v), and the gel was incubated in the buffer (100 mL for one or two mini-gels) with gentle agitation for 30 minutes at room temperature. After incubation, the zymogram renaturing buffer was decanted and replaced with 1 × zymogram developing buffer (Tris-base, Tris-acid, NaCl, and CaCl2). The gel was equilibrated for 30 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation and replaced in the fresh 1 × zymogram developing buffer. After overnight incubation at 37°C, the product was stained for 30 minutes in the staining buffer (Coomassie Blue R-250, methanol, acetic acid and distilled water). Gels were destained with an appropriate Coomassie R-250 destaining solution (methanol : acetic acid : water [50 : 10 : 40, v/v]). Areas of protease activity appeared as clear bands against a dark blue background where the protease had digested the substrate.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the means ± SD. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test.

RESULTS

Involvement of inflammatory mediators in DSS-promoted colon carcinogenesis

In our previous studies, administration of a single i.p. dose of AOM (10 mg/kg) alone caused colon tumor formation in about 15% of treated mice with an average number of 1.7 tumors per mouse, while administration of 2% DSS alone in drinking water for 7 consecutive days failed to induce colon tumor formation. However, the administration of AOM followed by DSS in drinking water resulted in the 84% incidence of colon tumors (21 mice among 25 mice developed colon tumors) with the average number of 7.16 ± 2.7 tumors per mouse. Macroscopically, nodular, polypoid or caterpillar-like tumors were observed mostly in the middle and distal colon of animals treated with AOM plus DSS.

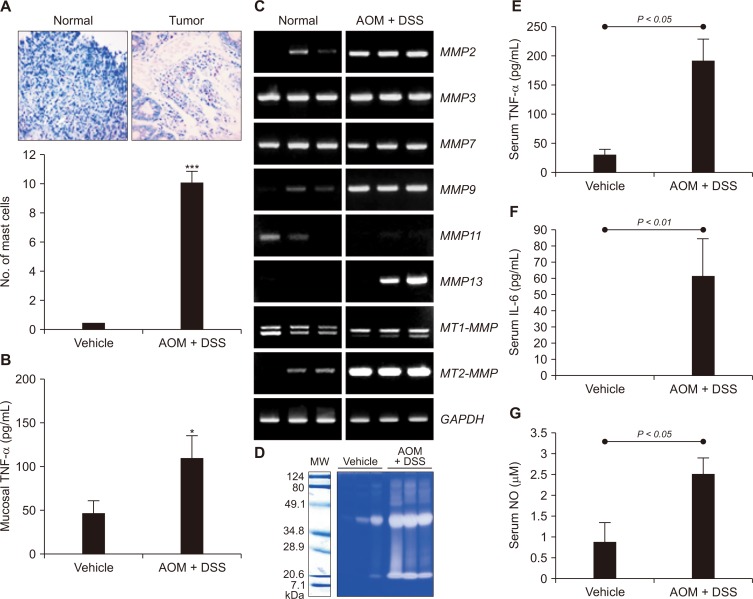

In order to determine whether DSS-induced colitis promoted colon carcinogenesis induced by AOM, we counted the number of mast cells. Mast cells are tissue-resident immune cells (granulocytes), which play a key role in inflammatory reactions [16]. The infiltration of mast cells has been considered to be associated with IBD [17] and inflammation-associated colon tumors [15,18]. Proportion of mast cells increased significantly in colon tumor of the AOM plus DSS-treated mice compared with the normal colonic mucosa (Fig. 2A). Since mast cells represent an important source of TNF-α, which is implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD, we measured the levels of this cytokine in colonic mucosa. As illustrated in Figure 2B, there was a significant increase in the colonic TNF-α production in mice treated with AOM plus DSS.

Figure 2. Footprints of inflammation in azoxymethane (AOM)-initiated and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-promoted colitis-associated carcinogenesis.

Mice given a single intraperitoneal dose of AOM (10 mg/kg) followed by exposure to 2% DSS in drinking developed colon tumors. (A) Mast cells were identified by tryptase immunostaining and counted. A statistically significant (***P < 0.001) increase of mast cells was noted in tumor tissues of the AOM plus DSS treated group (× 400 magnification). (B) Tissue levels of TNF-α. *Significantly different from the value of the control group (P < 0.05). (C, D) Expression of representative tissue matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). The expression of MMPs was measured by reverse transcription-PCR. (D) The catalytic activity of MMPs was assessed by the Gelatin zymography as described in Materials and Methods. (E-G) Serum levels of interleukin (IL)-6, TNF-α, and nitric oxide (NO). Significantly higher levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and NO were noted in AOM + DSS group, suggesting inflammation contributed to colitic cancer. The experimental details are described in the Materials and Methods. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MW, molecular weight.

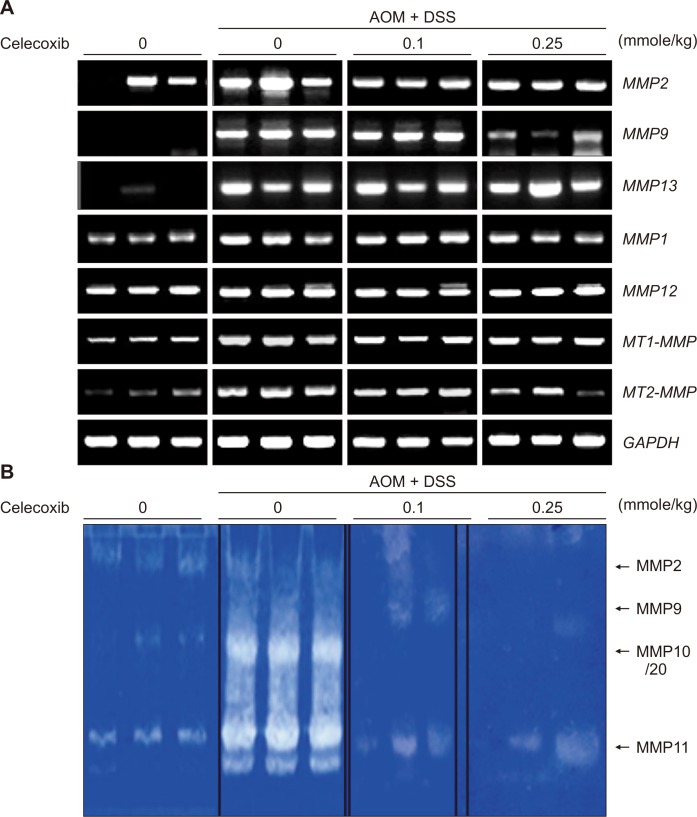

Enhanced expression and secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are essential for tumor invasion and metastasis [19]. Compared with the normal distal colon, the AOM plus DSS-treated colon exhibited markedly elevated expression of some MMPs, such as MMP2, MMP9, MMP13, and MT2-MMP (Fig. 2C) as well as their catalytic activities determined by zymography (Fig. 2D). In addition, the serum levels of TNF-α, interleukin-6, and nitric oxide were significantly increased in the AOM plus DSS-treated mice (Fig. 2E-2G).

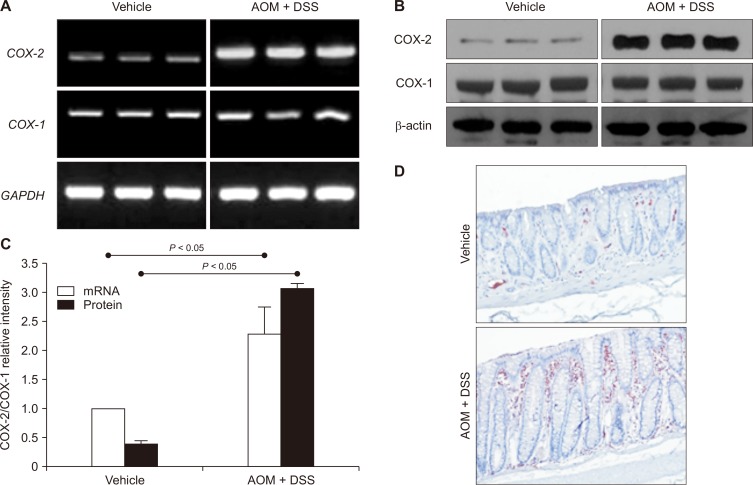

Upregulation of COX-2 expression in colitis-associated cancer

Inappropriately elevated expression of COX-2 has been implicated in pathogenesis of inflammation-associated malignancies including colitic cancer [12,20]. COX-2 expression was significantly increased at both transcriptional (Fig. 3A) and translational (Fig. 3B) levels in the AOM plus DSS-treated group compared to the vehicle-treated control group. Repeated experiments showed a significant difference in the colonic COX-2 expression between the control and the AOM plus DSS-treated animals, with the ratio of COX-2/COX-1 mRNA and protein expression 2.3- and 6.7-fold higher, respectively in the colitis promoted tumors (Fig. 3C). By immunohistochemical staining, aberrantly enhanced expression of COX-2 was observed in infiltrated inflammatory cells and some epithelial layers of the colon tumor (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. (A, B) Upregulation of COX-2 in colitis-associated cancer as determined by (A) reverse transcription-PCR for COX-2 mRNA or (B) Western blot analysis for COX-2 protein in colonic tissues.

Expression of COX-2 as well as its mRNA transcript was significantly increased in the colon of azoxymethane (AOM) plus dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) treated mice compared to the mice in the vehicle group. (C) Comparison of the relative expression of COX-2 and COX-1 and their mRNA transcripts between the vehicle group and the AOM plus DSS group. (D) Immunohistochemical staining of COX-2. Aberrantly increased expression of COX-2 was observed in infiltrated inflammatory cells and some epithelial cells surrounding the tumor (× 100). GAPDH, glyceraldegyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Effect of pharmacologic COX-2 inhibition on AOM-initiated and DSS-promoted colon carcinogenesis

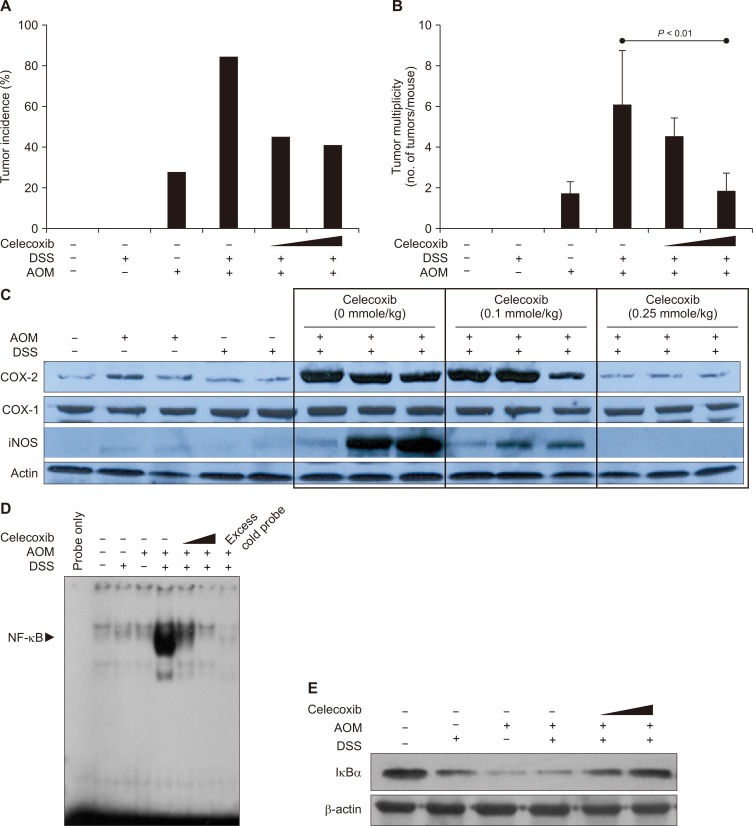

The findings that COX-2 was overexpressed in colitis-associated carcinogenesis prompted us to determine whether a pharmacologic inhibition of this pro-inflammatory enzyme could prevent DSS-promoted colon carcinogenesis. Oral administration of celecoxib (0.25 mmole/kg) for 14 consecutive weeks resulted in substantial reduction (83.3% vs. 44.4%) in the incidence (Fig. 4A) and the multiplicity (6.00 ± 2.75 vs. 1.75 ± 0.96 tumors/mouse, P < 0.01; Fig. 4B) of colon tumor formation induced by AOM plus DSS. Compared with colonic mucosa in control mice, the colonic tumor tissues from mice treated with AOM and DSS displayed markedly elevated COX-2 expression (Fig. 4C). The level of the house keeping-enzyme COX-1 remained unchanged. The oral administration of celecoxib inhibited the AOM plus DSS-induced expression of COX-2 and also iNOS, another prototypic pro-inflammatory enzyme, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Effects of the COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib on azoxymethane (AOM) plus dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colon carcinogenesis and pro-inflammatory signaling.

Mice were treated with a single intraperitoneal injection of AOM and/or subsequent administration of 2% DSS in drinking water for 7 weeks. Control animals were given the vehicle alone. Celecoxib (0.1 mmole/kg or 0.25 mg/kg) was given orally by gastric intubation for 14 weeks. (A, B) Tumor incidences and tumor multiplicities. (C) The expression of COX-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the colon of mice measured by Western blot analysis elevated. (D) DNA binding activity of NF-κB determined by the gel shift assay as described in Materials and Methods. (E) Inhibitory effects of celecoxib administration on IκBα degradation induced by AOM and DSS. The expression of IκBα was measured by Western blot analysis.

NF-κB regulates the expression of COX-2 and iNOS, and promotes inflammation-associated tumorigenesis [21]. Therefore, we determined whether celecoxib could suppress the activation of this transcription factor in the colon tissue of mice treated with AOM plus DSS. Under physiologic conditions, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by forming an inactive complex with IκBα protein. Upon exposure of cells to pro-inflammatory stimuli, IκBα translocation rapid phosphorylation and degradation. This allows release of NF-κB and translocation to the nucleus, where it binds to the promoter regions of target genes including COX-2 and thereby regulates their transcription [22]. Nuclear extracts from colonic mucosa of mice treated with AOM and DSS displayed the pronounced NF-κB DNA binding as assessed by the gel shift assay (Fig. 4D). Neither AOM nor DSS alone induced the DNA binding activity of NF-κB. Celecoxib dose-dependently inhibited AOM and DSS-induced DNA binding of NF-κB. Addition of 100 × excess cold probe of NF-κB negated the NF-κB DNA binding (Fig. 4D). AOM plus DSS treatment led to marked degradation of cytoplasmic IκBα (Fig. 4E), which accounts for the increased NF-κB DNA binding. Celecoxib treatment dose-dependently restored the IκBα level. Moreover, celecoxib inhibited upregulation of MMP-2, -9, and MT2-MMP induced by AOM plus DSS (Fig. 5A). Celecoxib treatment also suppressed the catalytic activities of MMPs, especially gelatinases represented by MMP-2 and -9 (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. (A) Effects of celecoxib on expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and (B) their activity in the colon tumors of mice treated with azoxymethane (AOM) and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS).

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

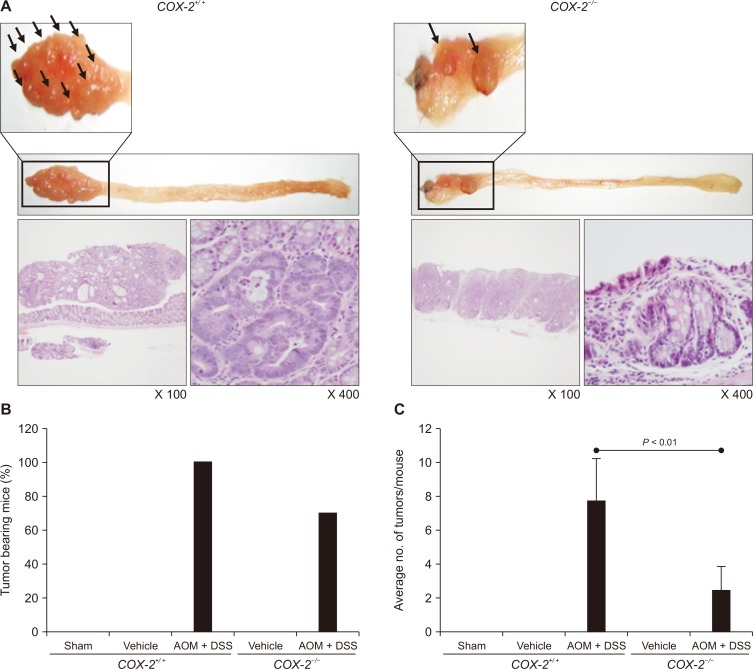

Effects of genetic disruption of COX-2 on AOM-initiated and DSS-promoted colon carcinogenesis

Besides the pharmacologic inhibition of COX-2 by a selective inhibitor, we determined whether ablation of COX-2 gene could inhibit colitis-associated colon carcinogenesis. When the AOM-induced and DSS-promoted colon carcinogenesis was compared in COX-2 wild type and knockout mice, the number and the size of tumors were much smaller in COX-2–/– mice than in COX-2+/+ mice (Fig. 6A). There were severe/thick dysplastic lesions, infiltration, and low-grade dysplasia in the colon of AOM plus DSS treated wild type (COX-2+/+) mice.

Figure 6. Effects of genetic ablation of COX-2 on azoxymethane (AOM)-initiated and dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-promoted colon carcinogenesis.

(A) Gross pictures showing coloitis-induced cancer and histological examination of colonic tissues by H&E staining in COX-2+/+ and COX-2–/– mice. (B, C) Comparison of (B) the tumor incidence and (C) the multiplicity of tumors formed in the colon of COX-2+/+ and COX-2–/– mice.

In COX-2 wild-type littermates (C57BL6 background), a single i.p. injection of AOM (10 mg/kg) followed by 1 week exposure to administration of 2% DSS in drinking water resulted in the 100% incidence of colon tumors with an average tumor multiplicity of 7.7 ± 2.5 tumors/mouse, whereas a 70% tumor incidence with an average of 2.43 ± 1.4 tumors in COX-2–/– mice (Fig. 6B and 6C).

DISCUSSION

In line with the findings that COX-2 expression is substantially increased in inflamed mucosa and further elevated in dysplastic and cancerous lesions [23], COX-2 inhibition by NSAIDs has been chemopreventive in familial or sporadic CRC [24,25]. In accord with results of our present study, celecoxib was proven to be effective in the prevention of colitis-associated tumorigenesis in a murine model of human IBD. We also found that COX-2 deficient mice were less susceptible than the wild-type mice to AOM-initiated and DSS-promoted colon carcinogenesis. Nonetheless, both pharmacologic inhibition and genetic ablation of COX-2 could achieve only a modest level of cancer prevention, indicative of COX-2-independent or other molecular mechanisms underlying colitis-induced carcinogenesis [26,27]. These include modulation of alternative eicosanoid pathways (e.g., 5-lipoxygenase, COX-1, etc.) and upstream signaling cascade changes (e.g., cytosolic phospholipase A2) [20] as well as iNOS-mediated promotion. As COX-1 also produces some pro-inflammatory prostaglandins with oncogenic potential, we speculate that this house keeping enzyme may also contribute to the development of CRC. In support of this supposition, the COX-1 selective inhibitor, mofezolac, protected against intestinal carcinogenesis in Apc gene knockout mice [28]. Notably, the combined treatment with both COX-1 and COX-2 selective inhibitors was found to be more effective in suppressing polyp growth than each inhibitor alone [29]. Therefore, an agent capable of inhibiting both COX-1 and COX-2 with no or minimal gastrointestinal toxicity, if any, could be developed as a better candidate for the prevention of colitis-associated cancer.

Celecoxib and some selective COX inhibitors prescribed for the treatment of arthritis, have been tested in human chemoprevention trials [30]. However, long-term use of COX-2 selective coxib drugs has caused some adverse effects on the cardiovascular system and unsatisfactory responsiveness. While short-term administration of celecoxib markedly inhibited adenoma growth in animal tumor models, uninterrupted long-term celecoxib administration to APCMin/+ mice, though initially regressed bowel tumors, resulted in gradual recurrence of tumors to the levels comparable to those attained in untreated controls [31]. As a plausible explanation for such contradictory results, celecoxib treatment may initially suppress COX-2 expression and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production, but a long-term use may produce paradoxically elevated levels of this molecule and reactivate PGE2-associated growth factor signaling pathways in either tumor or normal tissues [31]. This may explain why selective inhibition of COX-2 is only partially protective against colitis-induced CRC, and gradually become ineffective. Thus, celecoxib resistance appears to occur as a consequence of an acquired adaptation to changes in the crypt microenvironment associated with chronic intestinal inflammation and impaired acute wound-healing responsiveness [31].

It has also been reported that COX-2 deletion in myeloid and endothelial cells, but not in epithelial cells, exacerbates DSS-induced murine colitis and exhibited greater weight loss, increased clinical scores, and decreased epithelial cell proliferation than control littermates [8]. Such dual functions of COX-2 may account for a double-edged nature of NSAIDs [32]. Thus, it is likely that selective COX-2 inhibition is not necessarily satisfactory for the prevention of colitis-associated carcinogenesis, and coordinated targeting of COX together with other pro-inflammatory molecules should be considered in order to better achieve CRC chemoprevention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Robert Langenbach for his generous supply of COX-2 knockout mice. This work was supported by the National Center of Efficacy Evaluation for the Development of Health Products Targeting Digestive Disorders (NCEED) grant (A102063, to K.B. Hahm and Y.-J. Surh) from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea, and by a National Research Foundation grant (2010-0002052, Prof. K.B. Hahm) and the the Global Core Research Center (GCRC) grant (to Y.-J. Surh) from the National Research Foundation (NRF), Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baert F, Caprilli R, Angelucci E. Medical therapy for Crohn's disease: top-down or step-up? Dig Dis. 2007;25:260–6. doi: 10.1159/000103897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim YJ, Lee JS, Hong KS, Chung JW, Kim JH, Hahm KB. Novel application of proton pump inhibitor for the prevention of colitisinduced colorectal carcinogenesis beyond acid suppression. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:963–74. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim YJ, Hong KS, Chung JW, Kim JH, Hahm KB. Prevention of colitis-associated carcinogenesis with infliximab. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:1314–33. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendel J, Nielsen OH. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA in active inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1170–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taketo MM. COX-2 and colon cancer. Inflamm Res. 1998;47(Suppl 2):S112–6. doi: 10.1007/s000110050295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill S, Sinicrope FA. Colorectal cancer prevention: is an ounce of prevention worth a pound of cure? Semin Oncol. 2005;32:24–34. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy R. Sulindac in familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:615. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200208223470816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishikawa TO, Oshima M, Herschman HR. Cox-2 deletion in myeloid and endothelial cells, but not in epithelial cells, exacerbates murine colitis. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:417–26. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matuk R, Crawford J, Abreu MT, Targan SR, Vasiliauskas EA, Papadakis KA. The spectrum of gastrointestinal toxicity and effect on disease activity of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:352–6. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okayama M, Hayashi S, Aoi Y, Nishio H, Kato S, Takeuchi K. Aggravation by selective COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colon lesions in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2095–103. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9597-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langenbach R, Morham SG, Tiano HF, Loftin CD, Ghanayem BI, Chulada PC, et al. Prostaglandin synthase 1 gene disruption in mice reduces arachidonic acid-induced inflammation and indomethacin-induced gastric ulceration. Cell. 1995;83:483–92. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morham SG, Langenbach R, Loftin CD, Tiano HF, Vouloumanos N, Jennette JC, et al. Prostaglandin synthase 2 gene disruption causes severe renal pathology in the mouse. Cell. 1995;83:473–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishikawa TO, Herschman HR. Tumor formation in a mouse model of colitis-associated colon cancer does not require COX-1 or COX-2 expression. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:729–36. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lim H, Paria BC, Das SK, Dinchuk JE, Langenbach R, Trzaskos JM, et al. Multiple female reproductive failures in cyclooxygenase 2-deficient mice. Cell. 1997;91:197–208. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80402-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka T, Kohno H, Suzuki R, Yamada Y, Sugie S, Mori H. A novel inflammation-related mouse colon carcinogenesis model induced by azoxymethane and dextran sodium sulfate. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:965–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Payne V, Kam PC. Mast cell tryptase: a review of its physiology and clinical significance. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:695–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton MJ, Frei SM, Stevens RL. The multifaceted mast cell in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2364–78. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bischoff SC, Lorentz A, Schwengberg S, Weier G, Raab R, Manns MP. Mast cells are an important cellular source of tumour necrosis factor alpha in human intestinal tissue. Gut. 1999;44:643–52. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.5.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zucker S, Vacirca J. Role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:101–17. doi: 10.1023/A:1025867130437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Limongelli V, Bonomi M, Marinelli L, Gervasio FL, Cavalli A, Novellino E, et al. Molecular basis of cyclooxygenase enzymes (COXs) selective inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;23:5411–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913377107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang D, DuBois RN. Pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and progression of colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;267:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang D, Dubois RN. The role of COX-2 in intestinal inflammation and colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:781–8. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breynaert C, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G. Dysplasia and colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a result of inflammation or an intrinsic risk? Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2008;71:367–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giardiello FM, Hamilton SR, Krush AJ, Piantadosi S, Hylind LM, Celano P, et al. Treatment of colonic and rectal adenomas with sulindac in familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1313–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305063281805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, Redston M, Solomon SD, Kim K, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:873–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du H, Li W, Wang Y, Chen S, Zhang Y. Celecoxib induces cell apoptosis coupled with up-regulation of the expression of VEGF by a mechanism involving ER stress in human colorectal cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2011;26:495–502. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cervello M, Bachvarov D, Cusimano A, Sardina F, Azzolina A, Lampiasi N, et al. COX-2-dependent and COX-2-independent mode of action of celecoxib in human liver cancer cells. OMICS. 2011;15:383–92. doi: 10.1089/omi.2010.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitamura T, Kawamori T, Uchiya N, Itoh M, Noda T, Matsuura M, et al. Inhibitory effects of mofezolac, a cyclooxygenase-1 selective inhibitor, on intestinal carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1463–6. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.9.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitamura T, Itoh M, Noda T, Matsuura M, Wakabayashi K. Combined effects of cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitors on intestinal tumorigenesis in adenomatous polyposis coli gene knockout mice. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:576–80. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinbach G, Lynch PM, Phillips RK, Wallace MH, Hawk E, Gordon GB, et al. The effect of celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, in familial adenomatous polyposis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1946–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carothers AM, Davids JS, Damas BC, Bertagnolli MM. Persistent cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition downregulates NF-κB, resulting in chronic intestinal inflammation in the min/+ mouse model of colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4433–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright JM. The double-edged sword of COX-2 selective NSAIDs. CMAJ. 2002;167:1131–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]