Abstract

The PB1 C-terminal domain and PB2 N-terminal domain interaction of the influenza A polymerase, which modulates the assembly of PB1 and PB2 subunits, may serve as a valuable target for the development of novel anti-influenza therapeutics. In this study, we performed a systematic screening of a chemical library, followed by the antiviral evaluation of primary hits and their analogues. Eventually, a novel small-molecule compound PP7 that abrogated the PB1-PB2 association and impaired viral polymerase activity was identified. PP7 exhibited antiviral activities against influenza virus subtypes A (H1N1)pdm09, A(H7N9) and A(H9N2) in cell cultures and partially protected mice against lethal challenge of mouse-adapted influenza A (H1N1)pdm09 virus. Surprisingly, a panel of other subtypes of influenza virus, including A(H5N1) and A(H7N7), showed various degrees of resistance to the compound. Biochemical studies revealed a similar pattern of resistance on the impairment of polymerase activity. Molecular docking analyses suggested a PP7-binding site that appeared to be completely conserved among the subtypes of the virus mentioned above. Thus, we propose that alternative/additional binding site (s) may exist for the regulation of PB1-PB2 subunits assembly of influenza A virus.

Highlights

-

•

A novel small-molecule compound was identified to provide anti-influenza effect in vitro and in vivo.

-

•

An RT-qPCR based assay was modified to evaluate the polymerase activity of various subtypes of influenza viruses.

-

•

The PB1-PB2 assembly strategies of the trimeric polymerase complex might be stain/subtype specific.

1. Introduction

The limited therapeutic options against the influenza virus and increasing challenges in drug-resistance make the endeavor for next-generation antiviral agents imperative (Hayden and de Jong, 2011, Ison, 2011, Kelso and Hurt, 2012). Recent advances in the understanding of the molecular mechanisms of influenza A virus (IAV) replication have hinted at new avenues for the development of antiviral agents that target viral proteins (Das et al., 2010) or host factors (Muller et al., 2012). Generally, virus-targeting antivirals functionally inhibit the biological process of viral proteins, mostly enzymatic activities. Alternatively, they may block viral protein-protein interactions (PPI) that are essential for the virus replication machinery (Lou et al., 2014). Host-targeting antivirals inspect the host-virus battleground and focus on the cellular factors that are involved in the viral life cycle or host immune response. It is believed to be a more sophisticated strategy since they minimize the emergence of drug resistance (Watanabe and Kawaoka, 2015). Nevertheless, the virus-targeting antivirals, such as polymerase and protease inhibitors, will still be the major choice in the development of antiviral therapies, probably due to our more comprehensive understanding of their underlying mechanisms (Lou et al., 2014).

Recent progress on polymerase structures of bat influenza A virus (Pflug et al., 2014), human influenza B virus (Reich et al., 2014), and influenza C virus (Hengrung et al., 2015) have provided tremendous insights into the complex architecture of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). Functioning as the viral RNA synthesis machine, the RdRp can produce either cRNA or vRNA through de novo replication or viral mRNA transcription through ‘cap-snatching’. Functionally, PB1 houses the catalytic site for polymerase activity, while PB2 binds the cap structure of cellular pre-mRNA, which is cleaved by PA endonuclease and used as a primer for viral mRNA synthesis (Eisfeld et al., 2015). Structurally, this heterotrimeric complex is assembled through the inter-subunit interfaces between the PA C-terminal domain (PA-Cter) and the PB1 N-terminal domain (PB1-Nter) (He et al., 2008, Obayashi et al., 2008) and between the PB1 C-terminal domain (PB1-Cter) and the PB2 N-terminal domain (PB2-Nter) (Sugiyama et al., 2009). Undoubtedly, inhibition of the PA endonuclease (Yuan et al., 2016a) and PB2 cap-binding (Yuan et al., 2016c) are valid means in terms of the virus-targeting antivirals development. Another appealing strategy to inhibit RdRp function is to interfere with its proper assembly using PPI inhibitors. To this end, small molecule compounds targeting the PA-Cter and PB1-Nter interplay have been actively pursued since 2012 (Massari et al., 2016, Muratore et al., 2012, Yuan et al., 2016d). Intriguingly, anti-influenza agents targeting the PB1-Cter and PB2-Nter interface have never been reported yet.

Here we performed an ELISA-based screening of a chemical library (Kao et al., 2010) with 950 small-molecule compounds. Subsequently, primary hits and their analogues were further screened for antiviral potency. An IAV replication inhibitor (4E)-1-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)-4-[(4-ethoxyphenyl)methylidene]pyrazolidine-3,5-dione, designated PP7, was identified as a lead compound with a selectivity index around 350. We proceeded to evaluate its antiviral efficacy among different subtypes of IAV. Surprisingly, our results suggested a strain-specific antiviral effect of PP7, in which the compound suppressed virus replication of IAV pdmH1N1, H7N9 and H9N2, whereas being less effective against the infections of IAV H5N1 and H7N7.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells, viruses and small-molecule compounds

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells and human embryonic kidney 293T cells were maintained as described previously (Yuan et al., 2016d). Upon virus infection, the infected cells were maintained in FBS free medium supplemented with or without 1 μg/ml TPCK trypsin. A total of 6 strains/5 subtypes of influenza A virus, including A/Hong Kong/415742/2009(H1N1)pdm09, A/Hong Kong/156/1997(H5N1), A/Vietnam/1194/2004(H5N1), A/Netherlands/219/2003(H7N7), A/Anhui/1/2013(H7N9) and A/Hong Kong/1073/1999 (H9N2), were cultured in MDCK cells and used for in vitro antiviral tests. The mouse-adapted H1N1 strain, A/Hong Kong/415742Md/2009 (H1N1)pdm09 (Zheng et al., 2010), was propagated in embryonated hens' eggs and used for in vivo antiviral tests. All experiments with live viruses were conducted using biosafety level 2 or 3 facilities as described previously (Zheng et al., 2008, Zheng et al., 2010). All tested compounds were purchased from ChemBridge Corporation (San Diego, USA) unless specified. Peptides were synthesized by Cellmano Biotech Limited (Hefei, China) with >95% purity.

2.2. Expression and purification of full-length PB1 protein

The full-length PB1 protein was expressed in the 293F mammalian cell expression system (Invitrogen) and purified by His-tag affinity chromatography. Briefly, the 293F cell line was suspension cultivated in 293 free-style medium (Gibco) in an orbital shaker in a 37 °C incubator with a humidified atmosphere of 8% CO2. The mammalian expression plasmid pCMV3-His-PB1 with the H1N1 gene was transfected into the cells (106/ml) by polyethylenimine (PEI) transfection reagent (Longo et al., 2013). Transfected 293F cells were harvested 120 h post-transfection and cell pellets were lysed in I-PER protein extraction reagent (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The PB1 protein was purified from the soluble cell lysate using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen), followed by overnight dialysis in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. After that, the protein was concentrated and detected by western blot using anti-PB1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher) as described previously.

2.3. Mini-replicon assay

The inhibitory effect of the peptide or compounds on the polymerase activity of A/Hong Kong/415742/2009 (H1N1)pdm09 was evaluated using a mini-replicon assay (Yuan et al., 2015). Details of the protocol were specified in the Supplementary Materials.

2.4. Multi-cycle virus growth assay

A multi-cycle virus growth assay was applied to evaluate the antiviral activity of chemical compounds or peptide. Experimental procedures are outlined in the Supplementary Materials.

2.5. ELISA-based screening assay

Compounds were screened by a previously described ELISA (Muratore et al., 2012) with some modifications. Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with 200 ng/well of full-length His-PB1 protein at 4 °C for overnight and blocked at 37 °C for 1 h. After washing, increasing amounts of PB2-N-Biotin probe (3.75–1000 ng per well) were added to the wells and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, intensive washes were carried out, followed by the addition of streptavidin-HRP (Invitrogen) and TMB substrate. Absorbance was read at 450 nm on an ELISA plate reader (Tecan Sunrise). For the competitive binding assay, PB2-N-Tat, a PB2-Nter derived short peptide that fused with a cell-penetrating sequence Tat, was used as a positive control inhibitor (Suppl. Table 2). To prepare the reaction, serially-diluted peptide inhibitor (10,000–39 ng per well) was co-incubated with 100 ng/well of PB2-N-Biotin probe and added to the wells that had been coated with 200 ng/well of His-PB1.

2.6. Screening of small-molecule compounds

Primary screening was performed according to the conditions optimized in the competitive binding ELISA, in which a small molecule library with 950 compounds was applied. The chemical library was a collection of primary hits that showed anti-cytopathic effect (CPE) against influenza virus infection (Kao et al., 2010). Importantly, they were screened from over 50,000 artificial compounds that could interrogate most known targets for viral infection such as SARS coronavirus etc. (Kao et al., 2004). In brief, an individual compound (10 μg/ml) was mixed with 1 μg/ml of PB2-N-Biotin probe and co-incubated in the plates that were coated with 200 ng/well of full-length PB1 protein. Compounds which resulted in decreased values that were comparable to positive control (i.e. PB2-N-Tat) were selected. Next, a dose–response analysis was done to identify the ‘active’ compounds that consistently blocked the PB1 protein and PB2-N-Biotin binding. Afterwards, a secondary screening was performed with plaque reduction assay (Zheng et al., 2010) to evaluate the in vitro anti-H1N1 efficacies of the ‘active’ compounds, in which the compounds were serially-diluted (10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, and 0.625 μM) and only those exhibited dose-dependent plaque reductions were chosen for further study.

2.7. In vivo evaluation of antiviral effect

BALB/c female mice, 6–8 weeks old, were kept in biosafety level-2 housing and given access to standard pellet feed and water ad libitum. All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee in the University of Hong Kong (reference number CULATR 3721-15) and were performed in compliance with the standard operating procedures of the biosafety level-2 animal facilities. A total of 3 groups (10 mice/group) of mice were evaluated. After anesthesia, mice were intranasally (i.n.) inoculated with 20 μl of lethal dose of mouse-adapted A(H1N1)pdm09 virus. The therapeutic treatment was initiated 4 h post-virus-challenge. One group of mice was intranasally (i.n.) inoculated with 20 μl of 1 mg/ml of PP7 (1 mg/kg). The second group of mice was i.n. administered with 20 μl of 1 mg/ml of zanamivir (1 mg/kg) as a positive control. Zanamivir, with the brand name Relenza, is an influenza neuraminidase inhibitor that commonly prescribed in the prevention and treatment of human infection. The third group was i.n. inoculated with PBS as an untreated control. Two doses per day of PP7, zanamivir or PBS were i.n. administered for 2 days (total 4 doses/mouse). Animal survival and vital signs were monitored for 21 days or until death. Body weight loss over 20% was set as the humane endpoint. Additionally, three mice in each group were euthanized on day 4 post-challenge. Mouse lungs were collected for virus titration by plaque assay and RT-qPCR methods (Yuan et al., 2016b). Mouse survival rates of two challenge doses, i.e. 3 and 10 MLD50, were detected, in which the same regimen was applied as described above.

2.8. Quantification of viral mRNA, cRNA and vRNA

An RT-qPCR assay was performed to determine the abundance of viral mRNA, cRNA and vRNA, as a reflection of the viral polymerase activity in the presence or absence of PP7. The method was modified from a previous report (Kawakami et al., 2011). Briefly, different subtypes of the virus were inoculated into MDCK cells in a 24-well plate at 0.1 MOI. One hour after virus inoculation, the inoculum was removed and cells were maintained with or without 40 μM of PP7. At 15-h post-infection, total RNAs were extracted from the cell lysate using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). The viral cDNA was synthesized using tagged-primers of the NP gene, followed by Real-Time PCR detection (LightCycler, Roche) that were able to specifically distinguish and quantify influenza vRNA, cRNA and mRNA levels. The cellular β-actin mRNA was included as an internal control. Relevant primers were listed in Suppl. Table 1.

2.9. Molecular docking

The structure file of PB1-Cter bound with the PB2-Nter peptide, which was derived from the A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1) strain, was retrieved from the protein data bank (PDB: 2ZTT) (Sugiyama et al., 2009). Co-crystallized peptide ligand was removed from the structure. Docking was carried out with PatchDock (Schneidman-Duhovny et al., 2005) with the protein structure considered as a rigid body while ligands were fully flexible. One hundred docking solutions were computed for the PB1-Cter and PP7 interaction and all other parameters were set to default. The predicted models were refined by FireDock (Mashiach et al., 2008) and the best binding solution files were visualized and validated by Schrodinger maestro (Schrödinger). A second docking method, iGemDock algorithm (Hsu et al., 2011), was applied to confirm the result. Further details of PatchDock and FireDock are outlined in the Supplementary Materials.

3. Results

3.1. The PB2-Nter derived peptide inhibited influenza polymerase activity and virus replication

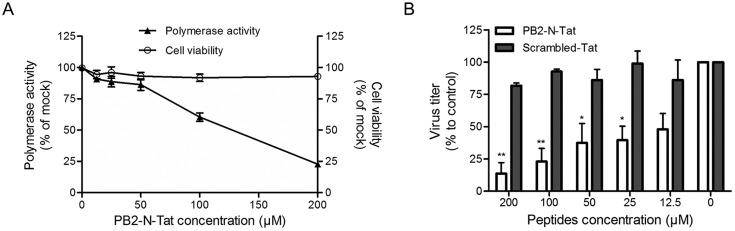

We hypothesized that viral RNA synthesis could be blocked by the specific inhibition of viral polymerase complex formation by targeting the hetero-oligomerization between PB1-Cter and PB2-Nter. Thus, a PB2-Nter derived short peptide (PB2-N) that may fulfill these criteria was tested (Reuther et al., 2011). To facilitate cell internalization, additional C-terminal amino acids (YGRKKRRQRRRPP) from the HIV transduction domain Tat were fused to PB2-N for the construction of PB2-N-Tat (Suppl. Table 2). To test whether PB2-N-Tat can disturb the formation of RdRp and affect its activity, a mini-replicon assay based on the A(H1N1)pdm09 genes was carried out in the presence or absence of the fusion peptide PB2-N-Tat. As shown in Fig. 1 A, the addition of PB2-N-Tat resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of reporter gene activity, whereas negligible cytotoxicity was detected. The result suggested that PB2-N-Tat was able to enter the cell and impair polymerase activity through blocking the PB1-PB2 interaction.

Fig. 1.

The PB2-Nter derived peptide inhibited influenza polymerase activity and virus replication. (A) The inhibitory effect of peptide PB2-N-Tat on viral polymerase activity (left y-axis) was tested by a mini-replicon assay, while its cytotoxicity to 293T cells (right y-axis) was determined by an MTT assay. In the mini-replicon assay, indicated concentrations of PB2-N-Tat were added at 5 h post-transfection. Luminescence and fluorescence were determined at 24 h post-transfection, respectively. In the MTT assay, PB2-N-Tat with various concentrations was incubated with 293T cells for 24 h before addition of MTT substrate. The experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated twice. Data are presented as mean values ± SD. (B) The antiviral effect of PB2-N-Tat was evaluated in MDCK cells using a multi-cycle virus growth assay. Cells were infected by A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza virus at MOI of 0.002. After virus internalization, the inoculum was removed, washed and replaced by culture medium containing peptides with indicated concentrations. A scrambled Tat-peptide was included as a negative control. Virus titers in the cell supernatant were collected at 24 h post-infection and determined by plaque assays. Results are presented as mean values + SD of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with the scrambled-Tat-treated group by unpaired t-test.

To further investigate whether PB2-N-Tat could suppress virus replication, virus titers in the supernatant of the A(H1N1)pdm09-infected were detected. A scrambled-Tat peptide consisting of the same amino acid composition as the PB2-N but randomized sequence was included as a negative control. As shown in Fig. 1B, PB2-N-Tat treatment caused a small reduction of virus titer when compared with that of the scrambled-Tat (p < 0.01 in 200 and 100 μM concentrations, p < 0.05 in 50 and 25 μM concentrations). Taken together, our results demonstrated that the fusion peptide PB2-N-Tat restrained influenza virus replication by impairing its polymerase activity. Thus, the PB2-N binding site on PB1 could serve as a druggable target for the development of novel anti-influenza therapeutics.

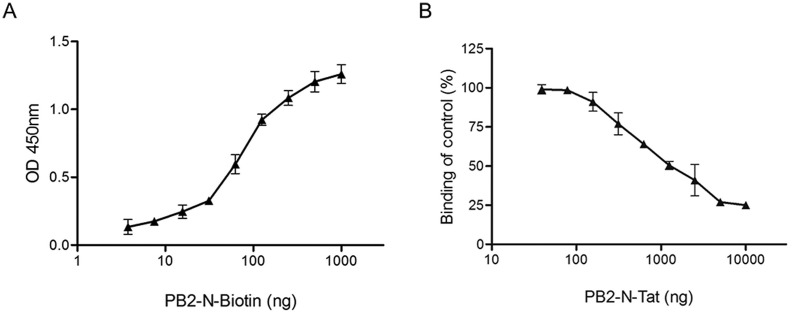

3.2. Modification of ELISA for screening of small molecule compounds

Compared to the antiviral peptides, small molecule compounds have the advantage of better bioavailability in vivo, especially in terms of an intracellular target such as the PB1-PB2 interface (Leeson and Springthorpe, 2007). We intended to identify compounds that were able to displace the binding of PB2-N peptide to PB1 protein, dissociate PB1-PB2 binding and thus decrease polymerase activity. To this end, an ELISA-based assay was modified to screen such kinds of compounds using His-tagged PB1-Cter protein as a receptor and biotinylated PB2-N peptide (PB2-N-Biotin, Suppl. Table 2) as a probe. Surprisingly, PB2-N-Biotin did not bind to PB1-Cter domain properly, exhibiting a narrow dynamic range and making the target protein unsuitable for drug screening (Suppl. Fig. 1). To address this issue, the full-length PB1 protein was applied. As shown in Fig. 2 A, in the plate coated with full-length PB1, addition of increasing amounts of PB2-N-Biotin resulted in greater absorbance. When the concentration of PB1 protein and PB2-N-Biotin probe were maintained at 200 ng/well and 100 ng/well respectively (molar ratio 1:10), the addition of PB2-N-Tat peptide, as a positive control, exhibited a dose-dependent reduction of absorbance (Fig. 2B). Collectively, the results demonstrated a specific binding between PB1 protein and PB2-N-Biotin peptide and suggested that ELISA was able to provide a broad dynamic range for the screening of PB1-PB2 binding inhibitors. The result also suggested that the conformational structure of PB1 was critical for PB1-PB2 binding.

Fig. 2.

Detection of PB1 protein and PB2-N peptide binding by ELISA. (A) The binding curve of PB2-N-Biotin peptide to His-PB1 protein was plotted, in which increasing amounts of PB2-N-Biotin (2-fold diluted from 1 μg/well) were added to wells coated with 200 ng/well of His-PB1. (B) The competitive binding curve of ELISA was shown, in which the peptide PB2-N-Tat was used as a positive control. Increasing concentrations of PB2-N-Tat (2-fold diluted from 10 μg/well) were incubated with 100 ng/well of PB2-N-Biotin probe and added together to the wells coated with 200 ng/well of His-PB1. For both assays, binding intensities were measured with the absorbance at 450 nm. The experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated twice for confirmation. Data are shown as the mean value ± SD.

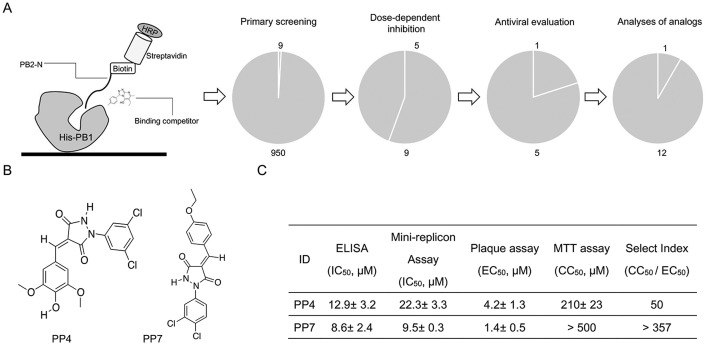

3.3. Identification of antiviral compounds

Compounds in the library were first screened at a fixed concentration of 10 μg/ml by ELISA, in which 9 compounds resulted in a decrease of binding intensity that was comparable to that of 10 μg/ml PB2-N-Tat peptide inhibitor. We proceeded to carry out a dose-response analysis to identify the compounds that consistently blocked the PB1 protein and probe binding. According to our result, five among 9 compounds were defined as ‘active’, with IC50 < 5 μg/ml (data not shown). Next, a cell-based plaque reduction assay was applied to identify the antiviral candidate(s) within the 5 ‘active’ compounds. Only one compound, namely PP4, reduced the plaque number in a concentration-dependent manner and was regarded as an antiviral effective compound. Based on the structural properties of PP4, twelve structurally similar analogues with drug-like properties (Lipinski, 2004) were purchased and applied to structure-activity analyses (Suppl. Excel file). Initially, analogues were evaluated for their inhibitory effect against PB1-PB2 binding, followed by plaque assays to determine the antiviral potency. Our result showed that only PP7 exhibited inhibition against both PB1-PB2 binding and the virus replication. Structurally, two chlorine atoms on the benzene ring were essential to maintain such inhibitions (Suppl. Excel file). The selectivity index (SI), i.e. the ratio of 50% cytotoxicity concentration (CC50) to half maximal effective concentration (EC50), was determined to compare PP4 and PP7 (Fig. 3 C). Due to the considerably higher SI, we selected PP7 to further evaluate its antiviral activities in vitro and in vivo.

Fig. 3.

Identification of antiviral compounds. (A) Schematic diagram of ELISA for screening of full-length PB1 protein and PB2-N peptide binding inhibitors, in which C-terminal biotinylated PB2-N peptide was used as a probe, while its binding to His-PB1 was detected by HRP-conjugated streptavidin substrate. A screening pipeline as well as the attrition rates from primary screening, dose-response analysis, antiviral evaluation and structure-activity analyses of analogues, are shown. (B) Chemical structures of the effective antiviral compounds after the systematic screening are shown. (C) Activities of anti-influenza effective compounds are summarized. Inhibitory effect of compounds against His-PB1 and PB2-N binding were evaluated by ELISA, while their inhibition against viral polymerase activity were measured by mini-replicon assays. Selectivity index (SI) of the compounds are shown, in which cell cytotoxicity (CC50) was examined in MDCK cells by MTT assays while antiviral efficacy (EC50) was tested against the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus infection by plaque reduction assay. SI was calculated as the ratio of CC50 to EC50.

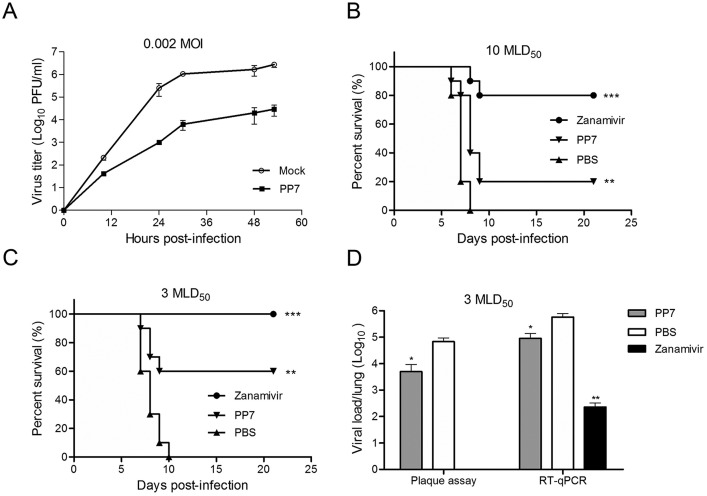

3.4. PP7 was effective against influenza H1N1 virus replication in vitro and in vivo

To evaluate the antiviral efficacy of PP7 in cell cultures, a multi-cycle virus growth assay was conducted. At 24 h post-infection (p.i.), the compound displayed dramatic anti-A(H1N1)pdm09 effects with 2–3 log10 reduction of viral titers in the supernatants (Fig. 4 A). To assess the antiviral effect of PP7 in vivo, mice challenged with either 10 MLD50 (Fig. 4B) or 3 MLD50 (Fig. 4C) of mouse-adapted A(H1N1)pdm09 virus were treated with PP7 or zanamivir as a positive control or PBS as a non-treated control. As shown in Fig. 4B, zanamivir-treated group showed 80% protection while survival rate in the PP7-treated group was 20% when mice were challenged with 10 MLD50 of the virus. Upon lower challenge dose, 60% of mice that received intranasal treatment with PP7 survived, while all mice died in the PBS-treated group (Fig. 4C). The survival rate in the zanamivir group was 100% (Fig. 4C). The results showed a significant improvement of mouse survival with the treatment of PP7 (p < 0.01) or zanamivir (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4B and C). When mice were infected with 3 MLD50 of challenge dose, the result demonstrated that PP7-treated group exhibited about a 10-fold reduction in viral load (p < 0.05) in the lung tissues as compared with the PBS-treated control group (Fig. 4D). Thus, we concluded that PP7 was able to provide some protection against the infection of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus in vitro and mouse-adapted A(H1N1)pdm09 in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Antiviral activities of PP7. (A) In vitro antiviral activity of compound PP7 was evaluated by a multi-cycle virus growth assay. Viral titers in the supernatants, in the presence or absence of 40 μM PP7, were determined by plaque assay at the indicated time-points. Data are represented as mean ± SD of two independent experiments. (B) In vivo antiviral efficacy of PP7 was measured in a lethal mouse model. Mice (10 per group) infected with 10 MLD50 of mouse-adapted A(H1N1)pdm09 virus were treated with 20 μl of 1 mg/ml PP7, 1 mg/ml zanamivir, or PBS by intranasal administration. Treatments started at 4 h after virus challenge and continued for 4 doses in 2 days (2 doses/day). Conditions of the mice were monitored for 21 days or till death. (C) The same treatment regimen was applied to mouse groups that were challenge with 3 MLD50 of mouse-adapted A(H1N1)pdm09 virus. Shown are the survival curves. For both (B) and (C), differences between groups were compared and analyzed using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. *** indicates p < 0.001 and ** indicates p < 0.01 as compared to PBS-treated group. (D) Mice were infected with 3 MLD50 of mouse-adapted A(H1N1)pdm09 virus. Three mice from each group were euthanized at day 4 post-infection and lungs were collected for detection of viral loads by plaque assay and RT-qPCR. The results are presented as the mean values + SD. Differences between groups were compared using the unpaired t-test. * indicates p < 0.05 and ** indicates p < 0.01 as compared to PBS-treated group. Infectious virus was undetectable in the zanamivir-treated mouse lungs using plaque assay.

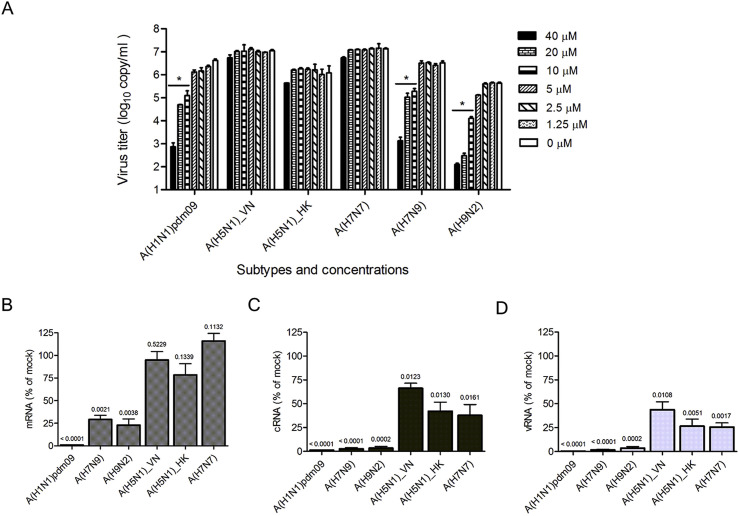

3.5. A panel of influenza A viruses showed various degrees of sensitivity to PP7

Since the amino acids among the IAV PB1-PB2 interact region were highly conserved (Fig. 6A), we assumed that PP7 might be capable of providing cross-protection against the infections of other IAV subtypes. To evaluate the cross-protection, we tested the inhibition of PP7 against a panel of IAV strains, including A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H5N1), A(H7N7), A(H7N9) and A(H9N2). It was found that the replication of A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H7N9) and A(H9N2) viruses was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5 A). Nevertheless, the PP7 treatment was unable to significantly inhibit A(H5N1) and A(H7N7) influenza viruses using as high as 40 μM. To determine if the rapid replication kinetics of A(H5N1) outpaced PP7 effectiveness, antiviral effects of earlier time points were evaluated. Our result showed that at neither 12 h nor 18 h post-infection could PP7 suppress the A(H5N1) virus replication (data not shown). Taken together, the results revealed a strain/subtype-specific inhibition of IAV replication by PP7. In order to further explore the various degrees of sensitivity to PP7, we looked into the viral polymerase activity by comparing the virus RNAs synthesis levels. As shown in Fig. 5B–D, mRNA, cRNA and vRNA levels were quantified in infectious contexts and presented as the ratio between PP7-treated and mock-treated samples. In the presence of PP7, significant decreases of mRNA syntheses were detected in A(H1N1)pdm09 (p < 0.0001), A(H7N9) (p = 0.0021) and A(H9N2) (p = 0.0038) virus-infected cells (Fig. 5B), whereas no significant difference was observed in the cells infected with the A(H5N1) and A(H7N7) viruses (p > 0.05, Fig. 5B). In terms of the cRNA and vRNA synthesis activities, all viral strains showed a reduced yield in the presence of PP7. However, A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H7N9), and A(H9N2) exhibited a more significant and substantial drop when compared with those of the A(H5N1) and A(H7N7) subtypes (Fig. 5C and D). In Fig. 5C, for example, p values were less than 0.0001 in A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H7N9) subtypes and equalled to 0.0002 in A(H9N2), whereas the p values in A(H5N1) and A(H7N7) subtypes were more than 0.01, which were about 100-fold higher than those of the former three. Thus, the results were compatible with the strain/subtype-specific antiviral effects and suggested that the varied sensitivity to PP7 correlated with the levels of impaired viral polymerase activity.

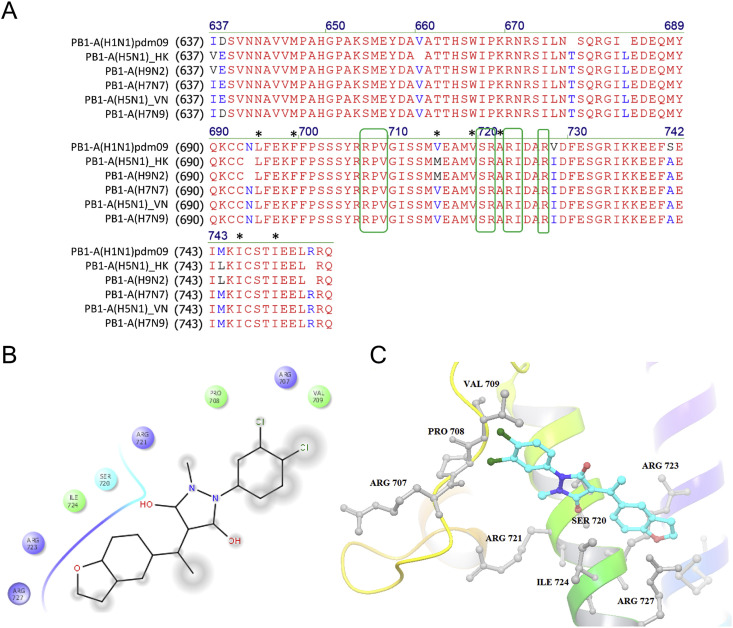

Fig. 6.

Sequence alignment and molecular docking analyses. (A) Sequence alignment of the PB1 C-terminal fragments (residues 678–757) from the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H5N1), A(H7N7), A(H7N9) and A(H9N2) virus strains are shown. Residues in red are identical between the 6 virus strains, while substitutions are in blue or purple. The predicted PP7 binding sites are highlighted with green boxes and shown to be completely conserved. The interface residues between PB1-Cter and PB2-Nter, as concluded from a previous crystal structure, are labeled with an asterisk. The alignment was done by Vector NTI (Life Technologies). (B) Two-dimensional docking analysis and (C) ribbon diagram of the interaction between PP7 and PB1-Cter are shown. Two chlorine atoms of PP7 contact with the amino acids Arg 707, Pro 708 and Val 709, while the remaining chemical groups interact with PB1-Cter through the residues Ser 720, Arg 721, Arg 723, Ile 724, and Arg 727. In the 3D structural analysis, chemical structure is shown as a stick model, whereas interacting amino acid residues are labeled in black. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 5.

Virus RNA synthesis activity upon PP7 treatment. (A) Virus copies in the supernatant were quantified, as a reflection of the antiviral effects of PP7 against infections of influenza virus A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H5N1), A(H7N7), A(H7N9) and A(H9N2). MDCK cells were infected with different strains/subtypes of IAV at MOI of 0.002 and treated with serial-diluted PP7 as indicated. Viral copies in the supernatant were determined at 24 h post-infection using RT-qPCR assay. The experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated twice. Data are represented as mean values + SD. Differences between various concentrations treatments were compared and analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. * indicates p < 0.05 as compared to mock-treated group. (B, C, D) Bar charts show the level of viral mRNA (B), cRNA (C), and vRNA (D) synthesis by different influenza virus polymerases, in the presence of PP7 treatment. MDCK cells were infected with indicated IAV at MOI of 0.1. After virus entry, cells were maintained with or without 40 μM of PP7, followed by total RNA extraction at 15- hour post-infection. Using specific primers for viral mRNA, cRNA, or vRNA, the production of each RNA type was separately assessed by RT-qPCR methods. The results are shown as the ratio between PP7-treated and mock-treated samples, with P values calculated by unpaired t-test. The data are presented as mean + SD for two independent experiments.

3.6. Molecular docking of PP7 with PB1-Cter

To further elucidate the mechanism underlying the strain-specific sensitivity to PP7, we aligned the sequences of PB1-Cter (residues 678–757) between virus strains. First, we looked into the key residues that determined the PB1-PB2 interface, such as the Leu 695, Phe 699, Val 715, Val 719, Ala 722, Ile 746, and Ile 750 (Sugiyama et al., 2009). The result showed that all of the 7 residues, except Val 715, were fully conserved in the 6 virus strains (asterisk marks, Fig. 6A). However, V715M substitution was detected in both PP7-sensitive and insensitive virus strains, e.g. A(H9N2) and A(H5N1-HK), so that the contribution of this amino acid substitution to the strain-specific sensitivity to PP7 might be excluded. Next, some residue substitutions in the other positions, such as V728I, S741A, and M744L were found, while none of them serves as a marker to distinguish the PP7-sensitive or resistant strains. Subsequently, we performed molecular docking analyses to predict potential binding sites that PP7 bound to. Since PP7 was screened as a PB2-N binding competitor, the compound was docked with the PB1-Cter domain directly. As predicted in Fig. 6B and C, significant salt bridge formed through the contacts between the hydroxyl of PP7 and Ser 720, Arg 721, Ile 724 of PB1-Cter domain and between the ethoxyphenyl and Arg 723, Arg 727, while the two chlorine atoms of PP7 interacted with the amino acids Arg 707, Pro 708 and Val 709. Intriguingly, all of the above 8 residues were completely conserved among the 6 virus strains that we tested (green boxes, Fig. 6A), which suggested that this binding site could not account for the differential sensitivity to PP7.

4. Discussion

Multiple lines of the evidence have demonstrated the PB1-PB2 interaction as a valuable protein-protein interaction target for the development of novel anti-influenza therapeutics (Sugiyama et al., 2009). A previous attempt of using short peptidic inhibitors derived from the PB2-binding domain of PB1 (i.e. PB1715-740 of PB1-Cter) to interfere with this interaction had failed (Ghanem et al., 2007). On the other side of such interaction, our study revealed that the PB2-Nter-derived peptide (PB21-37) impaired influenza polymerase activity and suppressed virus replication (Fig. 1). The result was in line with another study using a GFP fusion construct (PB21-37-GFP) to dissociate the PB1-PB2 complex (Reuther et al., 2011).

A mutagenesis study by Sugiyama and colleagues concluded that even a single substitution at the PB1-Cter interface could inhibit RNA synthesis (Sugiyama et al., 2009), which indicated that the interactive surface was small and the opportunity to develop small molecule PPI inhibitors was feasible. To verify this postulation experimentally, a competitive ELISA was utilized (Fig. 2), which enabled the initial identification of anti-influenza effective compounds (Fig. 3). Notably, one of the most effective compounds, PP7, was shown to provide protection against infection of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 in vitro and mouse-adapted A(H1N1)pdm09 in vivo (Fig. 4). PP7 exhibited modest in vivo anti-influenza activity when compared with the commercial available drug zanamivir (Fig. 4B–D), which was limited by its moderate bioavailability in vivo. On the other hand, it is worth noting that intranasal treatments, as we used in the study, may facilitate influenza virus infections and promote lung pathology (Smee et al., 2012). Apparently, drug delivery through intranasal route is direct and efficient. However, intranasal liquid also helps to spread the virus inside the mouse lungs (Taylor, 1941). Therefore, the treatment of influenza virus infections by the intranasal route requires additional optimization of virus challenge dose to avoid compromising the effectiveness of a potentially useful antiviral agent.

PP7 is a novel and artificially synthesized compound, whose biological testing results have never been mentioned before. However, it was surprising that the inhibition of virus replication by PP7 was strain/subtype-specific even though the drug target is highly conserved among various subtypes (Fig. 5A). The observation was in agreement with that reported by Reuther et al., where they concluded the different assembly strategies of influenza polymerase utilizing PB21-37-GFP fusion protein to target the PB1-PB2 interface (Reuther et al., 2011). To investigate the reasons for differential inhibition, we examined the sensitivity of IAV RdRp to PP7 and found that polymerase activity in PP7-resistant virus strains was less impaired (Fig. 5B–D). The RdRp of influenza A virus serves as the hub for viral transcription and replication (Reich et al., 2014). Traditionally, influenza polymerase activity is evaluated through mini-replicon assays (Fig. 1A). However, the cloning work becomes tedious in a scenario of measuring polymerase activities of several virus strains. To find an alternative, an RT-qPCR method was utilized (Fig. 5B–D). To determine the specificity of such assay, mini-replicon assays based on A(H1N1)pdm09 and H7N7 viral genes were carried out. As shown in Suppl. Fig. 3, polymerase activity in A(H1N1)pdm09 exhibited a dose-dependent and greater sensitivity to PP7 inhibition than that of the H7N7 group, which validated the role of RT-qPCR method as an alternative to mini-replicon assays. Importantly, the assay was able to quantify the mRNA, cRNA and vRNA synthesis activities across different virus subtypes of IAV. It took into account the context of an infectious event instead of the recombinant enzyme complex, thus may better recapitulate key physiological aspects of the polymerase activity.

To elucidate the discrepant observation between different influenza subtypes, first we speculated that structural variations between different PB1-Cter domains might play a role. Thus, sequence alignments focusing on the PB1-PB2 interactive residues as well as the predicted PP7-binding sites were carried out (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, docking simulation based on either the isolated PB1-PB2 complex (Fig. 6B and C) or the whole architecture of influenza A polymerase heterotrimer (Suppl. Fig. 5) were carried out. The result suggested that PP7 interacted with similar but not fully identical residues, whose difference might be due to (i) the structures of bat-specific influenza A polymerase differ from that of human/avian A strains (Pflug et al., 2014); (ii) PB1-PB2 conformation changes after the assembly of polymerase heterotrimer (Deng et al., 2005). However, our analyses suggested that none of the mentioned residues could account for the various degrees of sensitivity. Furthermore, PB2-N-Tat, which was shown to be anti-H1N1 effective (Fig. 1B), exerted similar specificity of antiviral efficacy as PP7 (Suppl. Fig. 2). To investigate whether substitution (s) in PB2-Nter could cause differences in susceptibility to PP7, an alignment of the tested viruses was carried out. The only one substitution at position 9, i.e. PB2 D9N/Y, was identified (Suppl. Fig. 4). However, its role in the strain-specific inhibition of IAV has been excluded in a previous report (Reuther et al., 2011). Taken together, it was speculated that either the molecular docking did not essentially identify the PP7 binding site, which was limited by the solely available but un-identical PB1 structures for docking simulation. Alternatively, additional binding locations beyond the one investigated in this study might exist to mediate the PB1-PB2 association even though theoretically PP7 binds to the conserved region across different subtypes. Consequently, the alternative PB1-PB2 interaction site(s) would be able to sustain the assembly of the polymerase complex of A(H5N1)-VN, A(H5N1)-HK, and A(H7N7), even when the contact between PB1-Cter and PB2-Nter was functionally blocked.

One of the previous mapping analyses on the functional domain of the influenza PB2 subunit revealed that the C-terminal domain of PB2 (residues 488–759, PB2-Cter) exhibited binding activity towards PB1 subunits (Poole et al., 2004). To verify if this is where the alternative binding site locates, we detected the interaction between PB1 subunit and PB2-Cter domain by using co-immunoprecipitation analysis and ELISA as tools. However, the results showed that the PB2-Cter failed to associate with the full-length PB1 in both experiments (data not shown), suggesting that the supposed PB1-PB2 binding site does not locate in this region. Another hypothesis proposed that the N-terminal domain of PA protein (PA-Nter) acted as a molecular mediator between the PB1-PB2 interplay, which is caused by the fact that it is PA-PB1 dimer, instead of the PB1 monomer, contacts with PB2 (Deng et al., 2005, Reuther et al., 2011). Thus, it is possible that conformational changes of PB1 are induced upon PA-PB1 binding. Consequently, in our case, the PA-PB1 dimer of A(H7N7) and A(H5N1) influenza virus might shield the binding site of PP7 by contacting PB2 through an alternative manner. To verify this, however, in-depth analyses to identify the decisive amino acid(s) in PA-Nter that distinguish PP7-resistant and sensitive virus strains shall be carried out in future studies.

Overall, in an effort to demonstrate the possibility of suppressing viral replication by abrogating the PB1-Cter and PB2-Nter binding, we confirmed the antiviral activity of a PB2-Nter derived peptide. In addition, we performed a systematic screening of a chemical library and identified a novel small-molecule compound PP7 with antiviral activities against influenza A virus, including A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H7N9) and A(H9N2) subtypes. However, the strain/subtype specific antiviral property of PP7 also suggested that alternative binding/mediating site(s), other than the PB1-Cter and PB2-Nter interface, may contribute to the PB1-PB2 association.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Innovation and Technology Commission, Government of Hong Kong SAR (UIM/278). We declared no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.11.005.

Contributor Information

Jie Zhou, Email: jiezhou@hku.hk.

Bo-Jian Zheng, Email: bzheng@hkucc.hku.hk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Das K., Aramini J.M., Ma L.C., Krug R.M., Arnold E. Structures of influenza A proteins and insights into antiviral drug targets. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:530–538. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng T., Sharps J., Fodor E., Brownlee G.G. In vitro assembly of PB2 with a PB1-PA dimer supports a new model of assembly of influenza A virus polymerase subunits into a functional trimeric complex. J. Virol. 2005;79:8669–8674. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8669-8674.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisfeld A.J., Neumann G., Kawaoka Y. At the centre: influenza A virus ribonucleoproteins. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015;13:28–41. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem A., Mayer D., Chase G., Tegge W., Frank R., Kochs G., Garcia-Sastre A., Schwemmle M. Peptide-mediated interference with influenza A virus polymerase. J. Virol. 2007;81:7801–7804. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00724-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden F.G., de Jong M.D. Emerging influenza antiviral resistance threats. J. Infect. Dis. 2011;203:6–10. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Zhou J., Bartlam M., Zhang R., Ma J., Lou Z., Li X., Li J., Joachimiak A., Zeng Z., Ge R., Rao Z., Liu Y. Crystal structure of the polymerase PA(C)-PB1(N) complex from an avian influenza H5N1 virus. Nature. 2008;454:1123–1126. doi: 10.1038/nature07120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengrung N., El Omari K., Serna Martin I., Vreede F.T., Cusack S., Rambo R.P., Vonrhein C., Bricogne G., Stuart D.I., Grimes J.M., Fodor E. Crystal structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from influenza C virus. Nature. 2015;527:114–117. doi: 10.1038/nature15525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu K.C., Chen Y.F., Lin S.R., Yang J.M. iGEMDOCK: a graphical environment of enhancing GEMDOCK using pharmacological interactions and post-screening analysis. BMC Bioinforma. 2011;12(Suppl. 1):S33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-S1-S33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ison M.G. Antivirals and resistance: influenza virus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011;1:563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao R.Y., Tsui W.H., Lee T.S., Tanner J.A., Watt R.M., Huang J.D., Hu L., Chen G., Chen Z., Zhang L., He T., Chan K.H., Tse H., To A.P., Ng L.W., Wong B.C., Tsoi H.W., Yang D., Ho D.D., Yuen K.Y. Identification of novel small-molecule inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus by chemical genetics. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:1293–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao R.Y., Yang D., Lau L.S., Tsui W.H., Hu L., Dai J., Chan M.P., Chan C.M., Wang P., Zheng B.J., Sun J., Huang J.D., Madar J., Chen G., Chen H., Guan Y., Yuen K.Y. Identification of influenza A nucleoprotein as an antiviral target. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:600–605. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami E., Watanabe T., Fujii K., Goto H., Watanabe S., Noda T., Kawaoka Y. Strand-specific real-time RT-PCR for distinguishing influenza vRNA, cRNA, and mRNA. J. Virol. Methods. 2011;173:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelso A., Hurt A.C. The ongoing battle against influenza: Drug-resistant influenza viruses: why fitness matters. Nat. Med. 2012;18:1470–1471. doi: 10.1038/nm.2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeson P.D., Springthorpe B. The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:881–890. doi: 10.1038/nrd2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipinski C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004;1:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo P.A., Kavran J.M., Kim M.S., Leahy D.J. Transient mammalian cell transfection with polyethylenimine (PEI) Methods Enzymol. 2013;529:227–240. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-418687-3.00018-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Z., Sun Y., Rao Z. Current progress in antiviral strategies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014;35:86–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashiach E., Schneidman-Duhovny D., Andrusier N., Nussinov R., Wolfson H.J. FireDock: a web server for fast interaction refinement in molecular docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W229–W232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massari S., Goracci L., Desantis J., Tabarrini O. Polymerase Acidic Protein-Basic Protein 1 (PA-PB1) Protein-Protein Interaction as a Target for Next-Generation Anti-influenza Therapeutics. J. Med. Chem. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller K.H., Kakkola L., Nagaraj A.S., Cheltsov A.V., Anastasina M., Kainov D.E. Emerging cellular targets for influenza antiviral agents. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;33:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratore G., Goracci L., Mercorelli B., Foeglein A., Digard P., Cruciani G., Palu G., Loregian A. Small molecule inhibitors of influenza A and B viruses that act by disrupting subunit interactions of the viral polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:6247–6252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119817109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obayashi E., Yoshida H., Kawai F., Shibayama N., Kawaguchi A., Nagata K., Tame J.R., Park S.Y. The structural basis for an essential subunit interaction in influenza virus RNA polymerase. Nature. 2008;454:1127–1131. doi: 10.1038/nature07225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflug A., Guilligay D., Reich S., Cusack S. Structure of influenza A polymerase bound to the viral RNA promoter. Nature. 2014;516:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nature14008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole E., Elton D., Medcalf L., Digard P. Functional domains of the influenza A virus PB2 protein: identification of NP- and PB1-binding sites. Virology. 2004;321:120–133. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich S., Guilligay D., Pflug A., Malet H., Berger I., Crepin T., Hart D., Lunardi T., Nanao M., Ruigrok R.W., Cusack S. Structural insight into cap-snatching and RNA synthesis by influenza polymerase. Nature. 2014;516:361–366. doi: 10.1038/nature14009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuther P., Manz B., Brunotte L., Schwemmle M., Wunderlich K. Targeting of the influenza A virus polymerase PB1-PB2 interface indicates strain-specific assembly differences. J. Virol. 2011;85:13298–13309. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00868-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneidman-Duhovny D., Inbar Y., Nussinov R., Wolfson H.J. PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W363–W367. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smee D.F., von Itzstein M., Bhatt B., Tarbet E.B. Exacerbation of influenza virus infections in mice by intranasal treatments and implications for evaluation of antiviral drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:6328–6333. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01664-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama K., Obayashi E., Kawaguchi A., Suzuki Y., Tame J.R., Nagata K., Park S.Y. Structural insight into the essential PB1-PB2 subunit contact of the influenza virus RNA polymerase. EMBO J. 2009;28:1803–1811. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R.M. Experimental Infection with Influenza a Virus in Mice: The Increase in Intrapulmonary Virus after Inoculation and the Influence of Various Factors Thereon. J. Exp. Med. 1941;73:43–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.73.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Kawaoka Y. Influenza virus-host interactomes as a basis for antiviral drug development. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015;14:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Chu H., Singh K., Zhao H., Zhang K., Kao R.Y., Chow B.K., Zhou J., Zheng B.J. A novel small-molecule inhibitor of influenza A virus acts by suppressing PA endonuclease activity of the viral polymerase. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22880. doi: 10.1038/srep22880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Chu H., Ye J., Hu M., Singh K., Chow B.K., Zhou J., Zheng B.J. Peptide-Mediated Interference of PB2-eIF4G1 Interaction Inhibits Influenza A Viruses' Replication in Vitro and in Vivo. ACS Infect. Dis. 2016;2:471–477. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.6b00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Chu H., Zhang K., Ye J., Singh K., Kao R.Y., Chow B.K., Zhou J., Zheng B.J. A novel small-molecule compound disrupts influenza A virus PB2 cap-binding and inhibits viral replication. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016 doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Chu H., Zhao H., Zhang K., Singh K., Chow B.K., Kao R.Y., Zhou J., Zheng B.J. Identification of a small-molecule inhibitor of influenza virus via disrupting the subunits interaction of the viral polymerase. Antivir. Res. 2016;125:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Zhang N., Singh K., Shuai H., Chu H., Zhou J., Chow B.K., Zheng B.J. Cross-Protection of Influenza A Virus Infection by a DNA Aptamer Targeting the PA Endonuclease Domain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:4082–4093. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00306-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Chan K.H., Zhang A.J., Zhou J., Chan C.C., Poon V.K., Zhang K., Leung V.H., Jin D.Y., Woo P.C., Chan J.F., To K.K., Chen H., Yuen K.Y. D225G mutation in hemagglutinin of pandemic influenza H1N1 (2009) virus enhances virulence in mice. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2010;235:981–988. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B.J., Chan K.W., Lin Y.P., Zhao G.Y., Chan C., Zhang H.J., Chen H.L., Wong S.S., Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Chan K.H., Jin D.Y., Yuen K.Y. Delayed antiviral plus immunomodulator treatment still reduces mortality in mice infected by high inoculum of influenza A/H5N1 virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:8091–8096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711942105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.