This population-based cohort study assesses the association of preeclampsia with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in term births in Norway.

Key Points

Question

Is preeclampsia linked to the neurodevelopment of offspring beyond its established association with cerebral palsy?

Findings

In this population-based birth cohort of 980 560 participants based on the Norwegian Medical Birth Registry, preeclampsia in term pregnancies was associated with an increased risk of cerebral palsy, autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, epilepsy, and intellectual disability in offspring.

Meaning

After excluding the possible role of preterm delivery, preeclampsia in term pregnancies was associated with an increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders among offspring.

Abstract

Importance

Preeclampsia during pregnancy has been linked to an increased risk of cerebral palsy in offspring. Less is known about the role of preeclampsia in other neurodevelopmental disorders.

Objective

To determine the association between preeclampsia and a range of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring after excluding preterm births.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective, population-based cohort study included singleton children born at term from January 1, 1991, through December 31, 2009, and followed up through December 31, 2014 (to 5 years of age), using Norway’s Medical Birth Registry and linked to other demographic, social, and health information by Statistics Norway. Data were analyzed from May 30, 2018, to November 17, 2019.

Exposures

Maternal preeclampsia.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Associations between preeclampsia in term pregnancies and cerebral palsy, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), epilepsy, intellectual disability, and vision or hearing loss using multivariable logistic regression.

Results

The cohort consisted of 980 560 children born at term (48.8% female and 51.2% male; mean [SD] gestational age, 39.8 [1.4] weeks) with a mean (SD) follow-up of 14.0 (5.6) years. Among these children, 28 068 (2.9%) were exposed to preeclampsia. Exposed children were at increased risk of ADHD (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 1.18; 95% CI, 1.05-1.33), ASD (adjusted OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.08-1.54), epilepsy (adjusted OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.16-1.93), and intellectual disability (adjusted OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.13-1.97); there was also an apparent association between preeclampsia exposure and cerebral palsy (adjusted OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.94-1.80).

Conclusions and Relevance

Preeclampsia is a well-established threat to the mother. Other than the hazards associated with preterm delivery, the risks to offspring from preeclampsia are usually regarded as less important. This study’s findings suggest that preeclampsia at term may have lasting effects on neurodevelopment of the child.

Introduction

Preeclampsia is a disorder of abnormal placentation, dysregulated vasculature, and maternal inflammation characterized by new-onset hypertension and organ dysfunction that affects approximately 4% of pregnancies.1,2,3 A leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, it is associated with adverse maternal outcomes including seizure (eclampsia), stroke, renal failure, and the hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome, as well as a long-term increase in maternal risk for cardiovascular disease.

Preeclampsia has been linked to cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in offspring.4,5,6 In a recent review by Maher and colleagues,5 evidence was insufficient to draw conclusions about the association of preeclampsia with other neurodevelopmental outcomes. Few studies to date have distinguished between term and preterm preeclampsia.

Children born to mothers with preeclampsia have alterations in cerebral blood flow and neuronal connectivity and are exposed to abnormal levels of proangiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in utero, supporting a possible causal role for preeclampsia in these outcomes.7 However, because the definitive treatment for preeclampsia is delivery, it is also a major cause of preterm birth, which may itself adversely affect neurodevelopment. The degree to which preterm birth is a mediator of the association between preeclampsia and neurodevelopment is unclear.

We investigated the association between maternal preeclampsia and a range of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring in a population-based prospective cohort, linking birth, health, and demographic registries in Norway. To reduce the influence of preterm birth as a mediator between preeclampsia and neurodevelopment, we restricted our analysis to children born at term.

Methods

Information on all pregnancies delivered in Norway after 16 weeks’ gestation is reported to the Medical Birth Registry of Norway at delivery by the mother’s clinician. The completeness of the birth registry is regularly evaluated by cross-referencing with the Central Population Register. For this cohort study, we identified all singleton live births from January 1, 1991, to December 31, 2009, defining term births as children born at a gestational age of at least 37 completed weeks by ultrasonographic measure if available and otherwise by last menstrual period. In vitro fertilization births were included, and gestational age was calculated as the fertilization date plus 2 weeks. We included all children who survived to 5 years of age. Participants were followed up until December 31, 2014, the most recent year for which full data are available, thus providing a minimum of 5 years of follow-up for all children. The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway and the registry owners approved this study with a waiver of informed consent for the use of public data. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

The birth registry provides information on maternal health, prenatal conditions, conditions at delivery, and newborn health. The diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia in Norway consist of proteinuria (defined as a finding of at least +1 on dipstick urinalysis or at least 0.3 g of protein in 24 hours) and elevated blood pressure after 20 weeks of gestation (defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg, an increase in systolic blood pressure ≥30 mm Hg, or an increase in diastolic blood pressure ≥15 mm Hg).8 Before 1999, preeclampsia was reported to the birth registry in a free-text field on the data collection form; since 1999, it has been reported by selection of checkboxes for mild preeclampsia, preeclampsia, preeclampsia before 34 weeks’ gestation, eclampsia, and HELLP syndrome.6,9

Since 1999, all cases of eclampsia reported to the birth registry are verified by hospitals. A validation study has compared preeclampsia diagnosis as recorded in the birth registry from 1999 to 2010 with clinical records.9 A record of preeclampsia in the birth registry had a positive predictive value of 84%, a specificity of 99%, and a sensitivity of 43%. Preeclampsia cases identified in the birth registry are therefore almost entirely confirmed cases, with an additional number of cases not captured.

Neurodevelopmental diagnoses of participants were obtained from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, codes in the National Insurance Scheme registry, as previously described.10 Data were linked across these population registries by each person’s unique Norwegian identification number. Demographic information and immigrant status were obtained from Statistics Norway. Parental educational levels are from the National Education Database. Death information was obtained from the Cause of Death Registry.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from May 30, 2018, to November 17, 2019. We examined a range of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes—cerebral palsy, ADHD, ASD, epilepsy, intellectual disability, and vision and hearing loss—and investigated the association between exposure to preeclampsia and each outcome by logistic regression. We used general estimating equations with a compound symmetry covariance structure to account for clustering of births by mother. We adjusted our multivariable logistic analyses for participant sex and year of birth, maternal age, parity, maternal marital status, maternal and paternal educational levels, and parental immigrant status. Year of birth was included as a continuous variable. Maternal age was categorized as 19 years or younger, 20 to 24 years, 25 to 29 years, 30 to 34 years, 35 to 39 years, or 40 years or older. Parity was dichotomized as primiparous or multiparous. Maternal and paternal educational levels were reported on a scale ranging from 0 (no education) to 8.0 (doctoral degree) and modeled as continuous variables. Participants were considered the children of immigrants if both parents were born outside Norway. Participants missing information on any covariates were excluded from the adjusted analyses. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) are reported with 95% CIs. In a sensitivity analysis, we recalculated crude and adjusted ORs after including all pregnancies (preterm and term) to confirm an overall association of preeclampsia with neurodevelopmental outcomes.

To assess the possible effect of confounding by unmeasured factors after adjustment for available covariates, we calculated the E-value for each adjusted OR, which denotes the degree to which 1 or more unobserved confounders would need to increase the risk of exposure and outcome to fully account for the observed associations.11 These analyses were conducted using Stata, version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC).

Maximum likelihood estimation in logistic regression can be biased in the case of rare events. We therefore conducted a sensitivity analysis using the Firth method for penalized likelihood estimation in logistic regression.12 These analyses were conducted in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Odds ratios were virtually unchanged (altered by 0.05 or less).

Results

A total of 983 805 singleton live births at term were recorded in Norway from 1991 to 2009. Of those, 2595 children (0.3%) died before 5 years of age and 650 (0.1%) were lost to follow-up, leaving 980 560 children available for analysis (48.8% female and 51.2% male; mean [SD] gestational age, 39.8 [1.4] weeks). Mean (SD) follow-up was 14.0 (5.6) years. Of these participants, 28 068 (2.9%) had been exposed to preeclampsia in utero, and 273 of these cases progressed to eclampsia. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Among these term births, participants exposed to preeclampsia were born slightly earlier than those unexposed (mean [SD] gestational age, 39.3 [1.5] vs 39.8 [1.4] weeks), with lower birth weights (mean [SD], 3463 [605] vs 3628 [494] g). Exposed children were more likely to be first births (60.8% vs 40.2%) and less likely to have immigrant parents (5.2% vs 8.1%). Information was missing for at least 1 covariate for 41 625 (4.2%) participants; those with missing information were more likely to have immigrant parents compared with offspring with full information on covariates (50.5% vs 6.2%) (eTable in the Supplement).

Table 1. Cohort Characteristics Among Term Singleton Live Births.

| Characteristic | Exposed to preeclampsiaa | |

|---|---|---|

| No (n = 952 492) | Yes (n = 28 068) | |

| Gestational age, mean (SD), wk | 39.8 (1.4) | 39.3 (1.5) |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), g | 3628 (494) | 3463 (605) |

| Female sex | 464 904 (48.8) | 13 367 (47.6) |

| Mother married or with partner | 875 701 (91.9) | 25 584 (91.2) |

| Mother’s age, y | ||

| ≤19 | 24 603 (2.6) | 1056 (3.8) |

| 20-24 | 161 504 (17.0) | 5768 (20.6) |

| 25-29 | 331 916 (34.8) | 9792 (34.9) |

| 30-34 | 295 853 (31.1) | 7533 (26.8) |

| 35-39 | 119 269 (12.5) | 3308 (11.8) |

| ≥40 | 19 323 (2.0) | 611 (2.2) |

| Educational level, mean (SD)b | ||

| Mother | 4.6 (1.7) | 4.6 (1.6) |

| Father | 4.4 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.7) |

| Immigrant parents | 77 462 (8.1) | 1462 (5.2) |

| First birth | 382 486 (40.2) | 17 064 (60.8) |

Data are from the Norwegian Medical Birth Registry and linked population registers from January 1, 1991, to December 31, 2009. At least 1 covariate was missing for 41 625 (4.2%) participants. Details on those with missing data are available in the eTable in the Supplement. Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as number (percentage) of participants.

Classified on a 9-level scale with 0 indicating no formal education and 8.0 indicating a doctoral degree. Level 4.0 indicates 13 years at school.

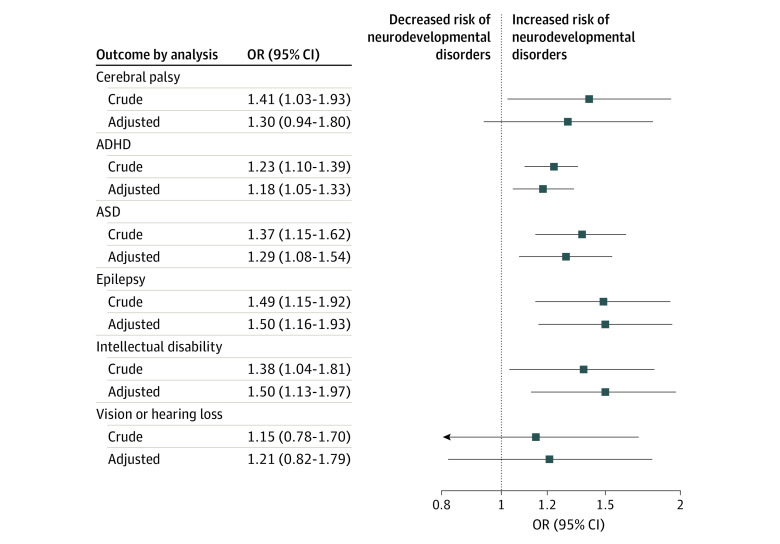

All adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes we assessed were more common among children exposed to preeclampsia (Table 2). Adjustment for sex, year of birth, maternal age, parity, maternal marital status, maternal and paternal educational levels, and parental immigrant status attenuated some of these associations but not all (Figure). After adjustment, children exposed to preeclampsia had a higher risk of ADHD (adjusted OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.05-1.33), ASD (adjusted OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.08-1.54), epilepsy (adjusted OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.16-1.93), and intellectual disability (adjusted OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.13-1.97), as well as a trend toward a higher risk of cerebral palsy (adjusted OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.94-1.80).

Table 2. Associations Between Preeclampsia Exposure and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes Among Term Singleton Birthsa.

| Outcome | Exposed to preeclampsia, No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 952 492) | Yes (n = 28 068) | Crude | Adjustedb | |

| Cerebral palsy | 965 (0.1) | 40 (0.1) | 1.41 (1.03-1.93) | 1.30 (0.94-1.80) |

| ADHD | 8313 (0.9) | 304 (1.1) | 1.23 (1.10-1.39) | 1.18 (1.05-1.33) |

| ASD | 3411 (0.4) | 137 (0.5) | 1.37 (1.15-1.62) | 1.29 (1.08-1.54) |

| Epilepsy | 1429 (0.2) | 63 (0.2) | 1.49 (1.15-1.92) | 1.50 (1.16-1.93) |

| Intellectual disability | 1307 (0.1) | 53 (0.2) | 1.38 (1.04-1.81) | 1.50 (1.13-1.97) |

| Vision or hearing loss | 787 (0.1) | 27 (0.1) | 1.15 (0.78-1.70) | 1.21 (0.82-1.79) |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; OR, odds ratio.

Data are from the Norwegian Medical Birth Registry and linked population registers from January 1, 1991, to December 31, 2009.

Adjusted for sex, year of birth, mother’s age, parity, marital status, maternal and paternal educational levels, and parental immigrant status.

Figure. Preeclampsia Exposure and Risk of Neurodevelopmental Disorders Among Term Singleton Births.

Data are from the Norwegian Medical Birth Registry and linked population registers from January 1, 1991, to December 31, 2009. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) represent ORs after adjustment for sex, year of birth, mother’s age, parity, maternal marital status, maternal and paternal educational attainment, and parental immigrant status. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. ADHD indicates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder.

Using E-value estimation, unmeasured confounders would themselves have to be associated with approximately double the risk for both the exposure and each outcome through independent pathways to eliminate the observed adjusted associations (Table 3). To assess the role of preeclampsia independently of gestational age, we repeated the main analysis for all term and preterm pregnancies. Results were nearly identical except for the 2 outcomes (cerebral palsy and vision or hearing loss) that did not meet strict criteria for statistical significance in our original analysis. These 2 effect estimates became considerably stronger when including preterm births: the adjusted OR was 2.26 (95% CI, 1.88-2.73) for cerebral palsy and 1.62 (95% CI, 1.22-2.16) for vision or hearing loss (Table 4).

Table 3. Sensitivity Analysis of Unmeasured Confounding.

| Outcome | E-value analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| Adjusted ORa | Lower confidence limitb | |

| Cerebral palsy | 1.92 | NA |

| ADHD | 1.64 | 1.28 |

| ASD | 1.90 | 1.37 |

| Epilepsy | 2.37 | 1.59 |

| Intellectual disability | 2.37 | 1.51 |

| Vision or hearing loss | 1.71 | NA |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio.

Indicates the minimum association that the confounders would have to have with both exposure and outcome to explain away the observed adjusted ORs.

Indicates the minimum association that confounders would have to have with both exposure and outcome to move the lower confidence limit to include the null. NA indicates lower confidence limit starts below 1.00.

Table 4. Associations Between Preeclampsia Exposure and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes Among All Preterm and Term Singleton Birthsa.

| Outcome | Exposed to preeclampsia, No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 1 043 485) | Yes (n = 37 938) | Crude | Adjustedb | |

| Cerebral palsy | 1463 (0.1) | 126 (0.3) | 2.37 (1.97-2.84) | 2.26 (1.88-2.73) |

| ADHD | 9701 (0.9) | 449 (1.2) | 1.27 (1.15-1.40) | 1.23 (1.12-1.36) |

| ASD | 3827 (0.4) | 191 (0.5) | 1.37 (1.19-1.59) | 1.31 (1.12-1.52) |

| Epilepsy | 1665 (0.2) | 93 (0.2) | 1.52 (1.24-1.88) | 1.55 (1.25-1.92) |

| Intellectual disability | 1592 (0.2) | 80 (0.2) | 1.38 (1.10-1.73) | 1.51 (1.20-1.89) |

| Vision or hearing loss | 935 (0.1) | 52 (0.1) | 1.53 (1.15-2.02) | 1.62 (1.22-2.16) |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; OR, odds ratio.

Data are from the Norwegian Medical Birth Registry and linked population registers from January 1, 1991, to December 31, 2009.

Adjusted for sex, year of birth, mother’s age, parity, maternal marital status, maternal and paternal educational levels, and parental immigrant status.

Discussion

In this population-based cohort study of term births in Norway, children exposed to preeclampsia were at an increased risk of a variety of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, ranging from movement and seizure disorders to sensory disorders to disorders of communication, socioemotional development, and behavior. Although the outcomes themselves were rare among term births and the absolute increases in risk with maternal preeclampsia were small (Table 2), these risk estimates were robust to adjustment for social and demographic factors. Moreover, these associations suggest pathways by which prenatal conditions might increase the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders, as discussed below.

The present study is, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive evaluation of the association between maternal preeclampsia and neurodevelopment to date. It contributes to the growing evidence that preeclampsia is linked to increased risk of cerebral palsy, ASD, and ADHD5,6,13,14,15 and expands the range of possible effects to intellectual disability and epilepsy, for which previous research has been described as “inconsistent” and “contradictory.”5,16

The links between preeclampsia and neurodevelopment raise a complex analytic question. The association could reflect a direct causal effect or could be the result of shared factors, such as maternal inflammatory conditions, that increase the risk of both preeclampsia and adverse neurodevelopment.17,18,19 The mediating role of preterm delivery further complicates the analysis, especially because an adjustment for gestational age can induce collider-stratification bias.20 For example, preeclampsia can appear to be protective against cerebral palsy when restricting analysis to preterm births6,21 but not when considering pregnancies overall.14,15,22 Our incomplete understanding of the pathways that connect preeclampsia to neurodevelopment may contribute to the variability in findings of previous studies.

Our findings suggest that preeclampsia may have broad effects on neurodevelopment not mediated by preterm birth. Aside from cerebral palsy, most prior work on preeclampsia and neurodevelopment has focused on ASD and ADHD and has not been as complete as the current study. As reported in a recent systematic review,5 many past studies have relied on maternal reporting of exposure or outcomes, whereas others did not differentiate between pregnancy-induced hypertension and preeclampsia. Reports with more reliable ascertainment of offspring outcomes have often been restricted to inpatients.23 In a low-income cohort of children, Mann and colleagues24 identified an association between preeclampsia and increased risk for ASD. A population registry-based case-control study in Denmark25 did not establish an association between preeclampsia and ASD, although their underpowered study provided nearly the same risk estimate as ours. For ADHD, our findings are consistent with those of a case-control study in a managed care cohort,26 which found an association between preeclampsia and ADHD when restricting to term births and overall. A population-based case-control study in Western Australia27 found an elevated risk for ADHD among nonindigenous children exposed to preeclampsia. Finally, using the same data sources as the present study for an earlier period, Halmøy and colleagues28 described an association between exposure to preeclampsia and ADHD among adults.

Evidence of other neurodevelopmental outcomes in children exposed to preeclampsia is scant. An association between maternal preeclampsia and epilepsy has been posited since at least 1978,29 although with little further investigation. Consistent with our results, population-based cohorts in Denmark30 and South Carolina31 have reported associations with epilepsy in children born at term. Results from South Carolina32 also showed an association between preeclampsia and intellectual disability within a cohort limited to low-income participants.

Having a population-based design allows our results to be relatively unbiased by selection. Our large sample size also affords greater power than most, if not all, previous investigations. Information on maternal preeclampsia was prospectively obtained at delivery, avoiding recall bias. More severe preeclampsia or eclampsia may lead to stronger associations. We have no information on severity, and eclampsia itself was too uncommon (273 cases) for separate analysis. Our exposure ascertainment method no doubt missed some children exposed to preeclampsia; these missed cases are also more likely to be mild.9 Although our results may provide higher estimates of effect compared with an investigation that captured all preeclampsia, the more severe events we capture are more likely to be biologically and clinically significant.

Similarly, our reliance on neurodevelopmental outcomes that qualify for financial compensation focuses on cases that are more severe and therefore most likely to be clinically important. We cannot rule out the possibility of social selection in registration for these conditions, but given the relative homogeneity of the population, the free access to medical care, and the unrestricted availability of insurance compensation, it seems unlikely that strong social factors are at work. At the same time, our data lack granularity of information on outcomes. For instance, we were unable to assess associations between exposure to preeclampsia and subtypes of cerebral palsy or epilepsy.

Unknown and unmeasured confounding remains a limitation as with any observational study. Although we were able to adjust for a wide range of possible maternal, demographic, and socioeconomic confounders, we were unable to account for the possible confounding role of maternal smoking because the birth registry did not collect that information before 1999. Smoking is not likely to contribute to the strength of our results given that smoking reduces the risk of preeclampsia while being linked with higher rates of most neurodevelopmental disorders.

Using E-value estimation (Table 3), we found that the degree of possible unmeasured confounding required to explain our findings by moving the point estimate to the null would represent a stronger effect than any recognized factor. Unmeasured factors would not have to be so strong to move the CIs to include the null (Table 3). It is relatively unlikely that a series of individual confounders would together be sufficient to eliminate the observed associations because their effects would have to act through independent pathways to the wide range of covariates for which we have already controlled. Nevertheless, our point estimates of associations are only estimates, and mechanistically plausible confounders, such as maternal inflammation, could be explored in future studies that analyze biological samples during pregnancy.

We restricted our analyses to term births to remove the possible mediating influence of preterm birth. A further advantage of excluding preterm preeclampsia is that preeclampsia diagnosed before 37 weeks may be a biologically distinct entity from preeclampsia at term, with different causal effects on neurodevelopment.33 Nonetheless, we conducted a sensitivity analysis of all children, including those born preterm, to confirm an overall role of preeclampsia in neurodevelopment. Results were nearly identical for most outcomes but were substantially stronger for cerebral palsy and vision and hearing impairment—the 2 outcomes with the weakest associations among term births. These stronger associations when including preterm births (Table 4) are consistent with the known effects of preterm delivery on intraventricular hemorrhage (a risk factor for cerebral palsy) and retinopathy (a risk factor for vision impairment).

We were unable to assess whether the duration of a child’s exposure to preeclampsia in utero is important for neurodevelopmental outcomes because we did not have information on when preeclampsia first manifested during a given pregnancy. At least a portion of the associations could be due to delayed maternal presentation to care, resulting in a delay of delivery until term rather than during the recommended late preterm period. In theory, this delay could lengthen exposure to preeclampsia and presumably increase accompanying neurodevelopmental risk. The extent of this bias seems minimal given the universal access to high-quality prenatal care in Norway and the small expected magnitude of such an effect.

Biological effects of preeclampsia on the developing brain support a causal role for preeclampsia in neurodevelopment. Neuroimaging of children exposed to preeclampsia shows differences in regional brain volumes, abnormal connectivity, and decreased cerebral vasculature.34,35 In addition, the retina, which is a contiguous component of the central nervous system, is less well vascularized in those exposed to preeclampsia.36 Because abnormal vascular growth and function are central to the proposed pathogenesis of preeclampsia, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the fetus may also be affected by abnormal angiogenesis. In particular, levels of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1), a decoy receptor for the proangiogenic placental growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor, are elevated in mothers with preeclampsia throughout pregnancy and in cord blood of neonates at delivery.7,37,38 Induction of sFlt-1 expression produces a preeclampsia phenotype in rodent models, and an early human clinical trial suggests removal may improve maternal hypertension and end-organ function and prolong pregnancy, supporting a causative role in the development of preeclampsia.39,40,41 Increased sFlt-1 may in turn cause abnormal angiogenesis in the fetus by decreasing available circulating levels of placental growth factor.42,43 Investigation of possible brain vasculature abnormalities in patients with neurodevelopmental disorders, as well as evidence of any associations between proangiogenic and antiangiogenic factor levels in neonates and abnormal neurodevelopment, would help validate these proposed mechanisms. Similarly, preeclampsia is associated with maternal inflammation. Biological markers of inflammation during pregnancy might help to support the hypothesized connection between maternal inflammation and neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring.19

Limitations

In summary, our ascertainment of exposures and outcomes may have been limited to more severe cases; however, these cases are more likely to be biologically and clinically significant. Future studies may also be able to better characterize possible associations between preeclampsia and subtypes of neurodevelopmental disorders. We also did not have information on the duration of a child’s intrauterine exposure to preeclampsia. Finally, unmeasured confounding may bias our effect estimates, although the degree of this bias would have to be quite large to eliminate our observed associations.

Conclusions

We provide prospective, population-based evidence that maternal preeclampsia is associated not only with an increased risk for cerebral palsy in offspring but also with adverse neurodevelopment across a number of neurobehavioral domains, even with the milder form of preeclampsia found among term births. Exploration of the molecular mechanisms underpinning this association may uncover targets for prenatal screening or intervention that could benefit the health of the child.

eTable. Characteristics of Participants With and Without Missing Covariate Data

References

- 1.Ananth CV, Keyes KM, Wapner RJ. Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980-2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6564. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher SJ. Why is placentation abnormal in preeclampsia? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4)(suppl):S115-S122. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powe CE, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia, a disease of the maternal endothelium: the role of antiangiogenic factors and implications for later cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2011;123(24):2856-2869. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.853127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mol BWJ, Roberts CT, Thangaratinam S, Magee LA, de Groot CJM, Hofmeyr GJ. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):999-1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00070-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maher GM, O’Keeffe GW, Kearney PM, et al. Association of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy with risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):809-819. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strand KM, Heimstad R, Iversen AC, et al. Mediators of the association between pre-eclampsia and cerebral palsy: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2013;347:f4089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lara E, Acurio J, Leon J, Penny J, Torres-Vergara P, Escudero C. Are the cognitive alterations present in children born from preeclamptic pregnancies the result of impaired angiogenesis? focus on the potential role of the VEGF family. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1591. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skjaerven R, Wilcox AJ, Klungsøyr K, et al. Cardiovascular mortality after pre-eclampsia in one child mothers: prospective, population based cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e7677. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klungsøyr K, Harmon QE, Skard LB, et al. Validity of pre-eclampsia registration in the Medical Birth Registry of Norway for women participating in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study, 1999-2010. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014;28(5):362-371. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moster D, Lie RT, Markestad T. Long-term medical and social consequences of preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(3):262-273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(4):268-274. doi: 10.7326/M16-2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Firth D. Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika. 1993;80(1):27-38. doi: 10.1093/biomet/80.1.27 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kułak W, Okurowska-Zawada B, Sienkiewicz D, Paszko-Patej G, Krajewska-Kułak E. Risk factors for cerebral palsy in term birth infants. Adv Med Sci. 2010;55(2):216-221. doi: 10.2478/v10039-010-0030-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mann JR, McDermott S, Griffith MI, Hardin J, Gregg A. Uncovering the complex relationship between pre-eclampsia, preterm birth and cerebral palsy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2011;25(2):100-110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2010.01157.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trønnes H, Wilcox AJ, Lie RT, Markestad T, Moster D. Risk of cerebral palsy in relation to pregnancy disorders and preterm birth: a national cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56(8):779-785. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walsh S, Donnan J, Fortin Y, et al. A systematic review of the risks factors associated with the onset and natural progression of epilepsy. Neurotoxicology. 2017;61:64-77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ananth CV, VanderWeele TJ. Placental abruption and perinatal mortality with preterm delivery as a mediator: disentangling direct and indirect effects. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(1):99-108. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pariente G, Wainstock T, Walfisch A, Landau D, Sheiner E. Placental abruption and long-term neurological hospitalisations in the offspring. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33(3):215-222. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Z, Ma L, Luo K, et al. Chorioamnionitis in the development of cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6):e20163781. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Basso O. On the pitfalls of adjusting for gestational age at birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(9):1062-1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu CS, Nohr EA, Bech BH, Vestergaard M, Catov JM, Olsen J. Health of children born to mothers who had preeclampsia: a population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(3):269.e1-269.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blair E, Watson L; Australian Cerebral Palsy Register Group . Cerebral palsy and perinatal mortality after pregnancy-induced hypertension across the gestational age spectrum: observations of a reconstructed total population cohort. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(suppl 2):76-81. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchmayer S, Johansson S, Johansson A, Hultman CM, Sparén P, Cnattingius S. Can association between preterm birth and autism be explained by maternal or neonatal morbidity? Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):e817-e825. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mann JR, McDermott S, Bao H, Hardin J, Gregg A. Pre-eclampsia, birth weight, and autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(5):548-554. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0903-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsson HJ, Eaton WW, Madsen KM, et al. Risk factors for autism: perinatal factors, parental psychiatric history, and socioeconomic status. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(10):916-925. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Getahun D, Rhoads GG, Demissie K, et al. In utero exposure to ischemic-hypoxic conditions and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e53-e61. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva D, Colvin L, Hagemann E, Bower C. Environmental risk factors by gender associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2014;133(1):e14-e22. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halmøy A, Klungsøyr K, Skjærven R, Haavik J. Pre- and perinatal risk factors in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(5):474-481. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degen R. Epilepsy in children: an etiological study based on their obstetrical records. J Neurol. 1978;217(3):145-158. doi: 10.1007/BF00312956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu CS, Sun Y, Vestergaard M, et al. Preeclampsia and risk for epilepsy in offspring. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):1072-1078. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann JR, McDermott S. Maternal pre-eclampsia is associated with childhood epilepsy in South Carolina children insured by Medicaid. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;20(3):506-511. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffith MI, Mann JR, McDermott S. The risk of intellectual disability in children born to mothers with preeclampsia or eclampsia with partial mediation by low birth weight. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2011;30(1):108-115. doi: 10.3109/10641955.2010.507837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vatten LJ, Skjaerven R. Is pre-eclampsia more than one disease? BJOG. 2004;111(4):298-302. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00071.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rätsep MT, Paolozza A, Hickman AF, et al. Brain structural and vascular anatomy is altered in offspring of pre-eclamptic pregnancies: a pilot study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37(5):939-945. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mak LE, Croy BA, Kay V, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity in children born from gestations complicated by preeclampsia: a pilot study cohort. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018;12:23-28. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yesil GD, Gishti O, Felix JF, et al. Influence of maternal gestational hypertensive disorders on microvasculature in school-age children: the Generation R study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184(9):605-615. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeisler H, Llurba E, Chantraine F, et al. Predictive value of the sFlt-1:PIGF ratio in women with suspected preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):13-22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karumanchi SA. Angiogenic factors in preeclampsia: from diagnosis to therapy. Hypertension. 2016;67(6):1072-1079. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.06421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venkatesha S, Toporsian M, Lam C, et al. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat Med. 2006;12(6):642-649. doi: 10.1038/nm1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu F, Longo M, Tamayo E, et al. The effect of over-expression of sFlt-1 on blood pressure and the occurrence of other manifestations of preeclampsia in unrestrained conscious pregnant mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(4):396.e1-396.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thadhani R, Hagmann H, Schaarschmidt W, et al. Removal of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 by dextran sulfate apheresis in preeclampsia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(3):903-913. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015020157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlembach D, Wallner W, Sengenberger R, et al. Angiogenic growth factor levels in maternal and fetal blood: correlation with Doppler ultrasound parameters in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29(4):407-413. doi: 10.1002/uog.3930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luna RL, Kay VR, Rätsep MT, et al. Placental growth factor deficiency is associated with impaired cerebral vascular development in mice. Mol Hum Reprod. 2016;22(2):130-142. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gav069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Characteristics of Participants With and Without Missing Covariate Data