Abstract

This cohort study examines the frequency and characteristics of non–transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) hospitals that do or do not meet new surgical volume requirements compared with TAVR hospitals.

Medicare recently revised its national coverage determination (NCD) for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).1 The revised NCD outlines new hospital surgical volume requirements to begin a TAVR program, including at least 50 open-heart procedures during the previous year and 20 aortic valve procedures in the previous 2 years. We describe the frequency and characteristics of non-TAVR hospitals that meet and do not meet new surgical volume requirements and compared them with current TAVR hospitals.

Methods

Medicare Part A claims (January 1, 2015-December 31, 2016) were used to identify 1196 of 3471 acute care nonfederal hospitals (34.5%) that had procedure codes for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), or TAVR. This study was deemed exempt from institutional review board approval because it used deidentified secondary data sets. Characteristics from the 2016 American Hospital Association Annual Survey were available for 1189 of 1196 sample hospitals (99.4%): urban vs rural location, bed size (<300, 300-500, and ≥500), teaching status, onsite cardiac intensive care unit, and geographic region (East, Midwest, South, and West). Medicare impact files were used to define hospital safety-net status (top quartile of disproportionate share hospital index for low-income and uncompensated care) and high patient complexity status (top quartile of Medicare case mix index).

One-year open-heart volume was the sum of CABG and SAVR volumes from 2016 and 2-year aortic valve volume was the sum of SAVR volumes from 2015 and 2016. Total all-payer volumes were estimated by dividing Medicare volumes by 60%, which is the estimated Medicare payer mix for CABG and SAVR from publicly available data.2 A hospital was classified as (1) a current TAVR hospital if it performed at least 1 TAVR procedure in 2016, (2) acandidate TAVR hospital if it met open-heart and aortic valve volume requirements, or (3) an ineligible TAVR hospital. The geographical distribution of current and candidate TAVR hospitals and hospitals per 100 000 Medicare beneficiaries were displayed using hospital referral regions. Multinomial logistic regression was used to compare characteristics of candidate and ineligible TAVR hospitals vs current TAVR hospitals. Analyses were conducted using Stata, version 15 (StataCorp), and statistical significance was set at α = .05.

Results

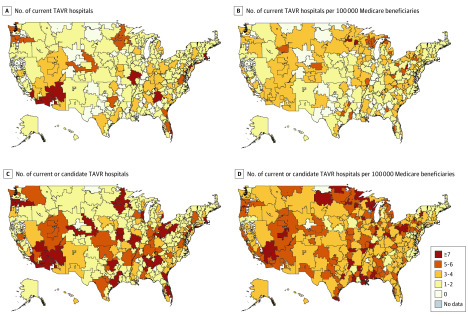

Our sample included 495 current TAVR hospitals (41.4%), 448 candidate TAVR hospitals (37.7%), and 246 TAVR-ineligible hospitals (20.7%). Wide variation existed in the geographic distribution of 495 current TAVR hospitals and 943 current or candidate TAVR hospitals (78.8%) across the hospital referral regions (Figure). Compared with current TAVR hospitals, candidate and ineligible TAVR hospitals were more likely to have fewer beds, be a safety net hospital, and treat less medically complex patients and less likely to have a cardiac intensive care unit (Table). Additionally, candidate hospitals were more likely to be non–teaching hospitals and ineligible TAVR hospitals were more likely to be rurally located.

Figure. Geographic Distribution of the Number of Current Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) Hospitals and the Number of Current or Candidate TAVR Hospitals Across Hospital Referral Regions.

A and B, A total of 355 hospitals. C and D, A total of 834 hospitals.

Table. Adjusted Comparison of Hospital Characteristics Between Candidate vs Current TAVR Hospitals and Ineligible vs Current TAVR Hospitals.

| Hospital characteristic | Hospitals, No. | Current TAVR hospitals, No. (%) | Candidate TAVR hospitals | Ineligible TAVR hospitals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | aOR (95% CI) | P value | No. (%) | aOR (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Overall | 1189 | 495 (41.6) | 448 (37.7) | NA | NA | 246 (20.7) | NA | NA |

| Location | ||||||||

| Urban | 1123 | 486 (43.3) | 426 (37.9) | 1 [Reference] | .61 | 211 (18.8) | 1 [Reference] | .01 |

| Rural | 66 | 9 (13.6) | 22 (33.3) | 1.27 (0.51-3.13) | 35 (53.0) | 3.46 (1.33-8.98) | ||

| Bed size | ||||||||

| ≥500 | 263 | 217 (82.5) | 36 (13.7) | 1 [Reference] | NA | 10 (3.8) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 300-499 | 378 | 186 (49.2) | 145 (38.4) | 3.43 (2.18-5.41) | <.001 | 47 (12.4) | 3.71 (1.69-8.13) | <.001 |

| <300 | 548 | 92 (16.8) | 267 (48.7) | 10.4 (6.28-17.2) | <.001 | 189 (34.5) | 26.8 (12.0-59.9) | <.001 |

| Teaching status | ||||||||

| Teaching | 786 | 415 (52.8) | 253 (32.2) | 1 [Reference] | .04 | 118 (15.0) | 1 [Reference] | .05 |

| Nonteaching | 403 | 80 (19.9) | 195 (48.4) | 1.48 (1.02-2.14) | 128 (31.8) | 1.57 (0.99-2.48) | ||

| Onsite cardiac ICU | ||||||||

| Yes | 703 | 394 (56.1) | 227 (32.3) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 82 (11.7) | 1 [Reference] | |

| No | 486 | 101 (20.8) | 221 (45.5) | 1.85 (1.32-2.61) | 164 (33.7) | 3.48 (2.26-5.36) | <.001 | |

| Safety net statusa | ||||||||

| Non–safety net | 856 | 360 (42.1) | 354 (41.4) | 1 [Reference] | .001 | 142 (16.6) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Safety net | 333 | 135 (40.5) | 94 (28.2) | 1.96 (1.32-2.92) | 104 (31.2) | 8.59 (5.23-14.1) | ||

| Patient case mix complexityb | ||||||||

| High complexity | 600 | 372 (63.2) | 289 (48.2) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 | 188 (31.3) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Low complexity | 589 | 123 (20.5) | 159 (27.0) | 4.46 (3.16-6.30) | 58 (9.9) | 9.00 (5.65-14.3) | ||

| Geographic region | ||||||||

| East | 351 | 201 (57.3) | 109 (31.1) | 1 [Reference] | NA | 41 (11.7) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Midwest | 311 | 114 (36.7) | 130 (41.8) | 2.08 (1.36-3.19) | .001 | 67 (21.5) | 2.38 (1.34-4.24) | .003 |

| South | 272 | 74 (27.2) | 113 (41.5) | 3.24 (2.03-5.16) | <.001 | 85 (31.3) | 5.17 (2.85-9.38) | <.001 |

| West | 255 | 106 (41.6) | 96 (37.7) | 1.55 (0.97-2.46) | .07 | 53 (20.8) | 1.71 (0.91-3.20) | .10 |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; ICU, intensive care unit; NA, not applicable; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

Defined as Medicare hospitals in the top quartile of the disproportionate share hospital index.

Defined as Medicare hospitals in the top quartile of the case mix index.

Discussion

The number of cardiac surgical hospitals providing TAVR could double under new surgical volume requirements. Candidate hospitals are different from current TAVR hospitals in several ways, including hospital size, resources, and patient case mix. Nevertheless, persistent variability in the geographic distribution of TAVR hospitals remains, with potentially limited access to TAVR in rural and safety net hospitals. This study is limited in that projected surgical volumes were based on 2015 to 2016 Medicare data and estimates of national payer mix, which may not accurately capture surgical or TAVR volumes or payer mixes. Finally, this study does not consider hospital percutaneous coronary intervention volume, and thus the number of projected candidate TAVR hospitals may be overestimated.

Continued research is needed to monitor the effect of the revised TAVR NCD.3 Specifically, tracking quality in hospitals with low TAVR volumes will be a critical challenge given the established volume-outcome association.4 Monitoring the location, characteristics, and procedural volumes of TAVR and non-TAVR hospitals will ensure access is expanding to areas of need rather than already existing markets.5,6

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Decision memo for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Accessed September 3, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=293&type=Open&bc=ACAAAAAAQCAA&

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality HCUPnet. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/

- 3.Bavaria JE, Tommaso CL, Brindis RG, et al. . 2018 AATS/ACC/SCAI/STS expert consensus systems of care document: operator and institutional recommendations and requirements for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a joint report of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(3):340-374. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vemulapalli S, Carroll JD, Mack MJ, et al. . Procedural volume and outcomes for transcatheter aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(26):2541-2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1901109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kundi H, Strom JB, Valsdottir LR, et al. . Trends in isolated surgical aortic valve replacement according to hospital-based transcatheter aortic valve replacement Volumes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(21):2148-2156. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strobel RJ, Likosky DS, Brescia AA, et al. . The effect of hospital market competition on the adoption of transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109(2):473-479. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]