Abstract

Endoscopic biliary stenting is an established modality of managing benign and malignant obstructive disorders of biliary tract. Complications associated with biliary stents though uncommon are on the rise. We report a case of migrated biliary plastic stent presenting as gastro-inetstinal hemorrhage, which was managed successfully by endoscopic technique avoiding any major surgery.

Keywords: Biliary stent, ERCP, hemorrhage, migration

Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangio pancreatography (ERCP) is an established minimal invasive technique of treating benign and malignant disorders of pancreatobiliary tract. Bleeding after ERCP is most commonly due to sphincterotomy.[1] Here, we describe an unsual case of gastro-intestinal bleed occurring due to migrated biliary stent following ERCP and biliary stenting.

Case Report

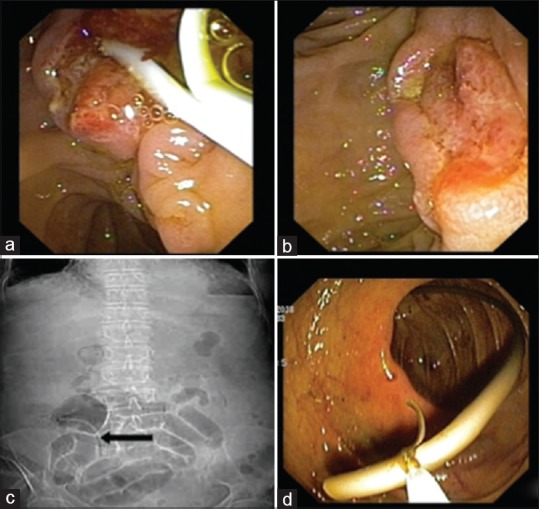

A 45-year-old man developed pain abdomen and melena 2 days after an ERCP and bile duct stenting, using a straight plastic stent with flaps [Figure 1a] for common bile duct stones associated with cholangitis. Physical examination revealed pallor and mild mid abdominal tenderness. Laboratory tests revealed a hemoglobin drop of 2 g/dl. Amylase and lipase values were normal. Suspecting a post-sphincterotomy bleed, duodenoscopy was done, which revealed no bleed at sphincterotomy site but stent could not be visualized at the papilla [Figure 1b]. Immediately, an erect abdominal X-ray [Figure 1c, Black arrow] was done, which showed a plastic stent lying in the right iliac fossa. There were no signs of perforation on X-Ray film. Repeat abdominal X-Ray 24 h later showed stent lying at the same location in right iliac fossa. As melena persisted, a colonoscopy was done a day later which showed the stent lying in caecum [Figure 1d] with few adjacent erosions and mild blood ooze. Stent was grasped by rat tooth forceps and removed during withdrawl of the colonoscope. His melena subsided 2 days post-procedure. It was speculated that the cause of significant melena was possibly the small bowel and caecal erosions caused by the migrated biliary stent which got impacted at the caecum. The patient improved with supportive treatment after removal of the stent.

Figure 1.

(a) Post EPT (endoscopic papillotomy) papilla with a plastic biliary stent in situ. (b) Post EPT papilla with no stent seen. (c) AXR (abdominal X-ray) erect showing migrated biliary stent in right iliac fossa. (d) Migrated biliary stent seen impacted in caecum

Discussion

Since first introduction by Soehendra and Reynders-Frederix in 1979, ERCP and stenting[2] has become an established modality for the management of pancreato-biliary disorders and often the first-line treatment option in most of these diseases, obviating the need of surgery.[3,4]

Common compilations of ERCP include pancreatitis, perforation, cholangitis, and hemorrhage.[1] With the increasing use of ERCP in management of pancreato-biliary disorders, stent-related complications are on the rise. Stent-related complications are primarily due to stent occlusion and stent migration. The most frequently encountered complication with biliary stents is that of stent block, leading to cholangitis. Stent migration (proximal or distal), on the other hand, is not very common. Other uncommon complications of biliary stenting include cholecystitis, bowel perforation, bleeding, pancreatitis, and stent fracture.[5,6,7]

Stent migration can occur both proximally (hepatic ducts)[8,9] and distally (intestinal lumen). Distal stent migration (~6%) is commoner than proximal. Stent migration depends upon several factors.[10] Stent-related factors include diameter, length, material, variety, and number of stents, while nature of biliary disease also has an impact on stent migration. Straight plastic stents migrate more often than metallic or double pigtail plastic biliary stents. Rate of migration is higher in benign biliary strictures as compared to malignant strictures. Malignant strictures, larger diameter stents, and shorter stents have been found to be significantly associated with proximal biliary stent migration.[10] Placement of multiple stents reduces the rate of migration.

Not all stents, which migrate, cause clinically relevant symptoms. Proximally migrated stents often cause obstructive jaundice and cholangitis. Most of the distally migrated stents are expelled spontaneously.[10] These stents can cause a variety of injuries with bowel perforation being the most common usually occurring in patients with diverticular disease, hernia, or intraabdominal adhesion.[11]

Rate of post ERCP gastrointestinal bleeding is about 1.3% and most of them are mild to moderate in severity.[1] Sphincterotomy is the commonest cause and is considered to be a high-risk procedure for post-ERCP bleeding. Stent-related bleeding is uncommon and only few case reports have been described.[12] Our present case highlights this unusual occurrence of gastrointestinal hemorrhage post ERCP, caused by dislodged stent leading to erosions and bleeding. Early detection and prompt endoscopic intervention in our case lead to a successful outcome and prevented further complications like bowel perforation. Even at the primary care level, a simple abdominal X-Ray (erect) in patients with such manifestations can diagnose migrated biliary stent and they can be timely referred for further management.

To conclude, migrated stents can cause severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage and should always be kept in the differential diagnosis of post ERCP bleed once sphincterotomy-related bleed has been excluded. In addition, prompt diagnosis and intervention is the key to success and can prevent life-threatening complications.

Declaration of patient consent

Informed Consent has been taken from the patient for publication of case report.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Anderson MA. Fisher L, Jain R, Evans JA, Appalaneni V, et al. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:467–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soehendra N, Reynders-Frederix V. Palliative bile duct drainage-A new endoscopic method of introducing a transpapillary drain. Endoscopy. 1980;12:8–11. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deviere J, Baize M, de Toeuf J, Cremer M. Long-term follow up of patients with hilar malignant stricture treated by endoscopic internal biliary drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(88)71271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deviere J, Devaere S, Baize M, Cremer M. Endoscopic biliary drainage in chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:96–100. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)70959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lowe GM, Bernfield JB, Smith CS, Matalon TA. Gastric pneumatosis: Sign of biliary stent-related perforation. Radiology. 1990;174:1037–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.174.3.174-3-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mueller PR, Ferrucci JT, Jr, Teplick SK, van Sonnenberg E, Haskin PH, Butch RJ, et al. Biliary stent endoprosthesis: Analysis of complications in 113 patients. Radiology. 1985;156:637–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.156.3.4023221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahoti S, Catalano MF, Geenen JE, Schmalz MJ. Endoscopic retrieval of proximally migrated biliary and pancreatic stents: Experience of a large referral center. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:486–91. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morimachi M, Ogawa M, Yokota M, Kawanishi A, Kawashima Y, Mine T. Successful endoscopic removal of a biliary stent with stent-stone complex after long-term migration. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2019;13:113–7. doi: 10.1159/000498914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Márquez HRB, Sanchez JSR, Jaimes ESC. Proximal migration of biliary stent: Case report. EC Gastroenterol Dig Syst. 2019;6.2:155–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johanson JF, Schmalz MJ, Geenen JE. Incidence and risk factors for biliary and pancreatic stent migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:341–6. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Namdar T, Raffel AM, Topp SA, Namdar L, Alldinger I, Schmitt M, et al. Complications and treatment of migrated biliary endoprostheses: A review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5397–99. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i40.5397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry PA, Karani J, Harrison PM. Colonic bleeding and a displaced biliary stent. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]