Abstract

Acanthamoeba are ubiquitous free-living amoeba. Acanthamoeba infections cause necrotizing vasculitis, resulting in vessel thrombosis and cerebral infarction. Acanthamoeba CNS infections, though uncommon, are associated with high mortality. Diagnosis is difficult and often delayed. Here, we present two immunocompetent hosts with Acanthamoeba encephalitis with good outcomes.

Keywords: Acanthamoeba CNS infections, Acanthamoeba encephalitis, granulomatous amoebic encephalitis

Introduction

Acanthamoeba are free-living protozoa found in soil, dust, and water.[1,2] Active trophozoites have acanthopodia and feed on bacteria, yeast, and algae. Dormant cysts are seen during unfavorable environmental conditions.[3] Cyst wall has strong glycosidic linkages that impart resistance to disinfection.[2,4]

Spectrum of disease includes keratitis, granulomatous encephalitis, meningoencephalitis, sinusitis, and skin lesions.[5,6,7,8] Risk factors include Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, malignancy, immunosuppressant drugs, and history of organ transplant.[9] Acanthamoeba CNS infections are associated with high mortality.[10,11] Here, we describe two immunocompetent patients with Acanthamoeba encephalitis.

Case History

Patient 1

A 51-year-old woman with no preexisting illnesses presented with high-grade fever and right-sided weakness for 4 days. She had history of falling into a well one month ago. Neck stiffness, hemiplegia, exaggerated deep tendon reflexes, and extensor plantar response on the right side were seen. The initial diagnosis was meningoencephalitis and we worked her up for various etiologies. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain revealed left middle cerebral arterial territory infarcts. CSF opening pressure, leucocyte count, and protein were elevated (27 cm water, 340 cells with 80% lymphocytes, and 86 mg/dl, respectively). In view of possible aspiration, CSF microscopy and culture (on nonnutrient agar with E. coli overlay) for Acanthamoeba was done. This was positive for Acanthamoeba cysts on day 4 [Figure 1]. CSF GeneXpert polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and mycobacteria growth indicator tube (MGIT) for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, bacterial, and fungal CSF cultures were negative. After positive Acanthamoeba culture report, combination therapy with rifampicin, fluconazole, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was initiated and planned for 6 weeks. At follow-up after one month of treatment, she was afebrile with residual right-sided hemiparesis.

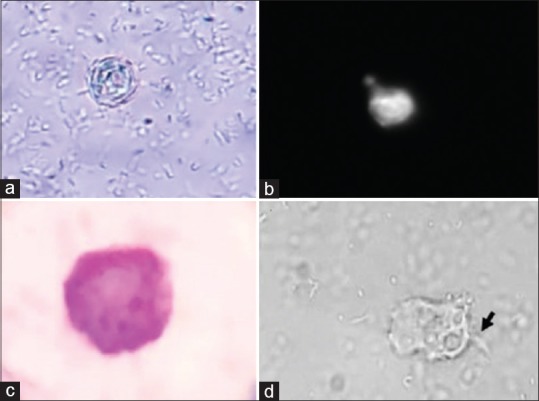

Figure 1.

Acanthamoeba cyst and trophozoite stages in CSF cultures from reported cases: (a) wet mount (400×) (b) calcofluor stain (400×) and (c) Giemsa stain (1000×) cyst in patient 1 and (d) trophozoites (400×) with acanthopodia (black arrow) in patient 2

Patient 2

A 22-year-old student presented with holocranial headache for 3 weeks. There was no history of fever, seizures, nasal discharge, loss of weight/appetite or aquatic activities. He had bilateral papilledema, without other neurological deficits. In this patient, we considered differential diagnoses of chronic meningitis, cerebral venous thrombosis and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. MRI brain was normal. CSF opening pressure was 28 cm water. CSF analysis showed two lymphocytes, with normal glucose and protein. CSF culture for bacteria, Mycobacteria (MGIT and GeneXpert PCR test) and fungi were negative. At this point, the possibility of Acanthamoeba infection was considered. CSF Acanthamoeba culture was positive on day 7 [Figure 1]. This patient was managed with fluconazole, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, metronidazole, rifampicin, miltefosine for 3 months. A decline in CSF opening pressure and resolution of headache were seen. He was well at follow-up 6 months after completion of therapy.

Both patients tested negative for HIV antibodies and had normal HbA1c levels.

Discussion

Acanthamoeba CNS infections are uncommon but frequently lethal. Acanthamoeba enter the body via inhalation/skin injuries followed by hematogenous dissemination and formation of cerebral ring-enhancing lesions.[12] Regions of brain involved include frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, cerebellum, and corticomedullary junction.[13] Brain autopsy specimens show necrotizing vasculitis.[3] On microscopy, venulitis, trophozoites/cysts in perivascular spaces, meningoencephalitis with lymphocytic/histiocytic infiltrate, and granulomatous lesions have been noted.[3,5,14] Though immunocompromised state is a risk factor, there are reports of severe disease in immunocompetent patients.[15,16,17]

Our first patient had history of fall into a freshwater body which may have led to the entry of Acanthamoeba. However, our second patient did not have similar history and was immunocompetent. There is limited data regarding prognostic factors, especially in immunocompetent hosts. We reviewed published cases of adult survivors (>15 years of age) of Acanthamoeba CNS infections from 1999 to 2019 indexed in Pubmed [Table 1]. 50% (4/8) were immunocompetent with no contact with water sources. However, Acanthamoeba are ubiquitous and history of no contact with water would not rule out infection. All survivors (8/8) received combination therapy and excision of brain lesions was done in 37% (3/8). Fluconazole was given in 62% (5/8), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in 50% (4/8), and miltefosine and rifampicin in 37% (3/8).

Table 1.

Selected Cases of Adult Survivors of Acanthamoeba Encephalitis in the last 20 years

| First Author; Year of Publication | Age/gender* | Immunocompromised state/risk factors-Yes/No | Clinical features | Diagnostic test | Imaging features | Treatment | Follow-up after treatment completion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sahly et al.[18]; 2017 | 38/M | Yes (HIV infection) | Headache | amebic forms on H and E stain; positive CSF PCR | Ring-enhancing lesion on MRI | miltefosine, fluconazole, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, flucytosine for 7 months | 5 months |

| Webster et al.[16]; 2012 | 38/M | No | Tinnitus, seizures | Brain biopsy H and E stain and PCR | Temporal lobe lesion | Surgical excision; voriconazole, miltefosine; 3 months | 3 years |

| Lackner et al.[19];2010 | 17/M | No | NM** | CSF | NM | meropenem, linezolid, moxifloxacin, fluconazole | NM |

| Sheng et al.[20]; 2009 | 63/M | Yes (h/o falling into ditch and aspirating water) | Headache, vomiting | CSF Wet-mount smear and Giemsa- trophozoites; CSF PCR | Cerebral lesions; leptomeningeal enhancement | Amphotericin B, rifampicin; 4 weeks | NM |

| Aichelburg et al.[21]; 2008 | 25/M | No | Fever, ataxia, cutaneous ulcers | CSF Acanthamoeba PCR | Multiple ring-enhancing lesions in cortex and brainstem | Trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole changed to sulfadiazine, fluconazole, miltefosine, amikacin; excision of cerebellar abscess | 2 years |

| Fung et al.[22]; 2007 | 41/M | Yes (Liver transplant, diabetes mellitus) | Fever, seizures | Frontal lobectomy sample-cysts | Frontal lobe lesions | Surgical excision, rifampicin, trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole; 3 months | 11 years |

| Petry et al.[23]; 2006 | 64/F | Yes (Diabetes mellitus, mid-facial fracture) | Headache | CSF culture | Pneumatocele | fluconazole, rifampin, metronidazole, sulfadiazine; 14 days. | 1 month |

| Hamide et al.[24]; 2002 | 45/F | No | Fever, signs of meningeal irritation | CSF wet mount and Giemsa | Normal | Rifampicin, fluconazole, trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole, albendazole, ceftriaxone. | 1 year |

*M: Male, F: Female; **NM: Not mentioned

Challenges in management include reduced drug delivery across blood-brain barrier and lack of cysticidal action of drugs. Presenting features can mimic common diseases like cerebrovascular accident and tumors which makes early diagnosis difficult.

Calcium-channel modulators and statins are being studied to look for anti-amoebic effects.[25,26]

Patients with meningoencephalitis should be asked about history of aquatic activities. However, negative history of contact with water bodies does not rule out CNS Acanthamoeba infections. Family medicine practitioners are often the first medical contact for such patients. Acanthamoebainfection should be suspected in patients with meningoencephalitis in whom no etiological organism has been found and those with multiple cerebral lesions. High index of suspicion among family medicine physicians may lead to better outcomes as early diagnosis and prompt initiation of therapy are crucial aspects of management.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Marciano-Cabral F, Cabral G. Acanthamoeba spp.as agents of disease in humans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:273–307. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.2.273-307.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunsuwansakul C, Mahboob T, Hounkong K, Laohaprapanon S, Chitapornpan S, Jawjit S, et al. Acanthamoeba in Southeast Asia – Overview and challenges. Korean J Parasitol. 2019;57:341–57. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2019.57.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddiqui R, Khan NA. Biology and pathogenesis of Acanthamoeba. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazuana T, Astuty H, Sari IP. Effect of cellulase enzyme treatment on cyst wall degradation of Acanthamoeba sp. J Parasitol Res. 2019;2019:16. doi: 10.1155/2019/8915314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandra SR, Adwani S, Mahadevan A. Acanthamoeba meningoencephalitis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2014;17:108–12. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.128571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanna V, Khanna R, Mukhopadhayay C, Shastri B, Anusha G. Acanthamoeba meningoencephalitis in immunocompetent: A case report and review of literature. Trop Parasitol. 2014;4:115. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.138540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Król-Turmińska K, Olender A. Human infections caused by free-living amoebae. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2017;24:254–60. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1233568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orosz E, Kriskó D, Shi L, Sándor GL, Kiss HJ, Seitz B, et al. Clinical course of Acanthamoeba keratitis by genotypes T4 and T8 in hungary. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2019;66:289–300. doi: 10.1556/030.66.2019.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz JH. Behavioral and recreational risk factors for free-living amebic infections. J Travel Med. 2011;18:130–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2011.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Megha K, Sehgal R, Khurana S. Genotyping of Acanthamoeba spp. isolated from patients with granulomatous amoebic encephalitis. Indian J Med Res. 2018;148:456–9. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1564_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das S, Saha R, Rani M, Goyal R, Shah D, Asish JK. Central nervous system infection due to Acanthamoeba: A case series. Trop Parasitol. 2016;6:88–91. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.175130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan NA. Acanthamoeba and the blood-brain barrier: The breakthrough. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:1051–7. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/000976-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ong TYY, Khan NA, Siddiqui R. Brain-eating amoebae: Predilection sites in the brain and disease outcome. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:1989–97. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02300-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thamtam VK, Uppin MS, Pyal A, Kaul S, Jyostna Rani Y, Sundaram C. Fatal granulomatous amoebic encephalitis caused by Acanthamoeba in a newly diagnosed patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Neurol India. 2016;64:101–4. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.173662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binesh F, Karimi M, Navabii H. Unexpected postmortem diagnosis of Acanthamoeba meningoencephalitis in an immunocompetent child. BMJ Case Rep 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.03.2011.3954. pii: bcr0320113954. doi: 10.1136/bcr. 03.2011.3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webster D, Umar I, Kolyvas G, Bilbao J, Guiot MC, Duplisea K, et al. Case report: Treatment of granulomatous amoebic encephalitis with voriconazole and miltefosine in an immunocompetent soldier. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:715–8. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghadage DP, Choure AC, Wankhade AB, Bhore AV. Opportunistic free: Living amoeba now becoming a usual pathogen? Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2017;60:601–3. doi: 10.4103/IJPM.IJPM_815_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Sahly H, Udayamurthy M, Parkerson G, Hasbun R. Survival of an AIDS patient after infection with Acanthamoeba sp. of the central nervous system. Infection. 2017;45:715–8. doi: 10.1007/s15010-017-1037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lackner P, Beer R, Broessner G, Helbok R, Pfausler B, Brenneis C, et al. Acute granulomatous Acanthamoeba encephalitis in an immunocompetent patient. Neurocrit Care. 2010;12:91–4. doi: 10.1007/s12028-009-9291-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheng WH, Hung CC, Huang HH, Liang SY, Cheng YJ, Ji DD, et al. First case of granulomatous amebic encephalitis caused by Acanthamoeba castellanii in Taiwan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:277–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aichelburg AC, Walochnik J, Assadian O, Prosch H, Steuer A, Perneczky G, et al. Successful treatment of disseminated Acanthamoeba sp. infection with miltefosine. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1743–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1411.070854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fung KT, Dhillon AP, McLaughlin JE, Lucas SB, Davidson B, Rolles K, et al. Cure of Acanthamoeba cerebral abscess in a liver transplant patient. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:308–12. doi: 10.1002/lt.21409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petry F, Torzewski M, Bohl J, Wilhelm-Schwenkmezger T, Scheid P, Walochnik J, et al. Early diagnosis of Acanthamoeba infection during routine cytological examination of cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1903–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.5.1903-1904.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamide A, Sarkar E, Kumar N, Das AK, Narayan SK, Parija SC. Acanthameba meningoencephalitis: A case report. Neurol India. 2002;50:484–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martín-Navarro CM, Lorenzo-Morales J, Machin RP, López-Arencibia A, García-Castellano JM, De Fuentes I, et al. Inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase and application of statins as a novel effective therapeutic approach against Acanthamoeba infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:375–81. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01426-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sifaoui I, Martín-Navarro C, López-Arencibia A, Reyes-Batlle M, Valladares B, Pinero J, et al. Optimized combinations of statins and azoles against Acanthamoeba trophozoites and cysts in vitro. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2019;12:283–7. [Google Scholar]