Abstract

Aim:

The present study was conducted to assess the presence of anemia in patients with advanced heart failure (HF) and compared the clinical characteristics of patients with anemia and without anemia.

Methodology:

The present study was conducted on 102 patients (60 males, 42 females) with advanced HF admitted in hospital. In all, general physical and clinical examinations were performed. All were subjected to complete blood count (CBC), hematocrit, and assessment of urea, creatinine, sodium, potassium, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). The levels of serum iron, ferritin, iron saturation, and iron-binding capacity were also evaluated. The causes of HF were assessed.

Results:

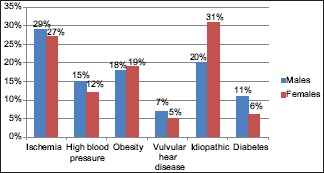

Mean age was 48.2 ± 5.7 and 42.2 ± 6.2 years in males and females patients, respectively. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 0.26 ± 0.8 in males and 0.24 ± 0.5 in females. 71.5% males and 76.3% females were on inotropic support. The etiology of HF was ischemia in 29% males and 27% females, high blood pressure in 15% males and 12% females, obesity in 18% males and 19% females, valvular heart disease in 7% males and 5% females, diabetes in 11% males and 6% females, and idiopathy in 20% males and 31% females. There was a significant difference in mean age, initial HB, final HB, hypertension, creatinine, BNP, and initial hematocrit level in patients with anemia and without anemia (P < 0.05). Deaths in hospital were also significant (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Anemia was seen in one-third of the patients with HF. Anemia was an independent marker with poor prognosis. Anemic patients were older than non-anemic patients.

Keywords: Anemia, hemoglobin, heart failure

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is considered one of the cause for hospitalisation which have higher mortality and morbidity.[1] Research has shown higher prevalence rate of anemia in patients with HF. Iron deficiency is the commonest of all nutrition deficiency all over the world. It has been found that the presence of anemia worsens HF. Earlier, hemoglobin level below 9 g/dL was considered positive for anemia. With every 1 g/dL fall in hemoglobin level, the chances of HF rise by 15.8%.[2,3]

Females are affected twice than males. The deficiency is due to regular blood loss in menstruation, increased demand in growing and pregnant females, etc., The prevalence of anemia varies from 10% to 60%. Several studies have documented the association of anemia in chronic heart failure (CHF).[4]

The etiology is multifactorial. Anemia may occur as a consequence of the disease or it may be the cause. Witte et al.[5] in their study revealed the fact that hematinic deficiency and poor nutrition in CHF patients lead to anemia. Means[6] stated that malabsorption, the use of anticoagulants in patients, and cardiac cachexia are other causative factors resulting in anemia. Insufficient erythropoietin or erythropoietin resistance, neurohumoral activation, and hemodilution are the other causes. Impairment of renal function, entrapment of iron in the reticuloendothelial system, obstruction of duodenal absorption, and hindrance of iron liberation from body stores may contribute to anemia in CHF.[7]

Erythropoietin synthesis serve as a major factor that associate anemia to the HF. Erythropoietin stimulates the production of red blood cells (RBCs), is produced primarily within the renal cortex and outer medulla by specialized peritubular fibroblasts, and is often abnormal in HF. Low Po2 is the primary stimulus for erythropoietin production. Renal dysfunction is common in HF, but structural renal disease, which could reduce erythropoietin production, is infrequent. However, an imbalance between oxygen supply and demand related to increased proximal tubular sodium reabsorption caused by low renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate reduces renal Po2, activates hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and induces erythropoietin gene transcription. Therefore, erythropoietin levels are increased in proportion to HF severity but are lower than expected for the degree of anemia, suggesting blunted erythropoietin production. However, the relationship between renal blood flow and erythropoietin secretion during HF is complex and not fully understood.[8]

The present study was conducted to assess the presence of anemia in patients with advanced HF and compared the clinical characteristics of patients with anemia and without anemia.

Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted in the Department of Cardiology and Internal Medicine after obtaining approval from intuitional ethical committee. It comprised 102 patients (60 males, 42 females) with advanced HF admitted in hospital. Patients’ age ranged 18–65 years with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <45%.

Patients with inflammatory diseases, excessive bleeding, presence of neoplastic diseases, and chronic infections were excluded. Those who had received blood transfusion in the last 3 months, those underwent surgery or were on iron supplements were not included in the study. Ethical clearance was obtained prior to the study and written informed consent was taken from the patients. Ethical approval was obtained from institutional ethical committe College of Medicine Abha, Saudi Arabia CMA Ref. No. Res.28/2017.

Patients’ information such as name, age, gender, etc., was recorded. In all, general physical and clinical examinations were performed. All were subjected to complete blood count (CBC), hematocrit, and assessment of urea, creatinine, sodium, potassium, and BNP. The levels of serum iron, ferritin, iron saturation, and iron-binding capacity were also evaluated.

The presence of features such as jugular stasis, pulmonary rales, edema in the sacral region, lower limb edema, or hepatomegaly was considered positive for the presence of congestion. Hemoglobin level less than 10 g% was considered for anemia in both genders. The patients were labeled with iron deficiency anemia when the serum ferritin concentration was lower than 100 ng/mL and the transferrin saturation was below 20%. Patients were checked for inactive area on electrocardiogram (ECG), history of coronary artery bypass grafting or coronary obstruction shown by cineangiography, and presence of hypertension. Primary valve alteration was checked before cardiomyopathy to rule out valvular heart disease.

Results thus obtained were subjected to statistical analysis using SPSS program (version 18.0). Chi-square test, student's t-test, and fisher's exact test were applied wherever necessary. P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Table 1 shows that the mean age in 60 male patients and 42 female patients were of 48.2 ± 5.7 and 42.2 ± 6.2 years, respectively. The sign of congestion was seen in 87% males and 89% females. LVEF was 0.26 ± 0.8 in males and 0.24 ± 0.5 in females. 71.5% males and 76.3% females were on inotropic support. Males spent 37.4 days and females 32.1 days in hospital. 12% males and 17% females died during hospitalization, whereas 36% males and 32% females died during monitoring. The difference was nonsignificant (P > 0.05). Graph 1 shows that etiology of HF was ischemia in 29% males and 27% females, high blood pressure in 15% males and 12% females, obesity in 18% males and 19% females, valvular heart disease in 7% males and 5% females, diabetes in 11% males and 6% females, and idiopathy in 20% males and 31% females.

Table 1.

Characteristics in patients with heart failure (HF)

| Parameters | Males | Females | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 60 | 42 | 0.21 |

| Age (Mean±SD) (years) | 48.2±5.7 | 42.2±6.2 | 0.1 |

| Signs of congestion | 87% | 89% | 0.5 |

| LVEF | 0.26±0.8 | 0.24±0.5 | 0.31 |

| Inotropic support | 71.5% | 76.3% | 0.21 |

| Days in hospital | 37.4 | 32.1 | 0.52 |

| Death during hospitalization | 12% | 17% | 0.1 |

| Death during monitoring | 36% | 32% | 0.5 |

P<0.05. LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

Graph 1.

Etiology of HF

Table 2 shows that 32% males and 35% females had anemia, HB at admission was 11.4 g/dL in males and 10.8 g/dL in females and at discharge it was 9.2 g/dL in males and 9.6 g/dL in females. The sodium (mEq/L) level was 136.2 and 137.8 in males and females, respectively. Creatinine (mg/dL) level was 1.8 and 1.7 in males and females, respectively. BNP (pg/mL) level was 1578 and 1521 in males and females, respectively. There was significant difference in mean age, initial HB, final HB, hypertension, creatinine, BNP, and initial hematocrit level in patients with anemia and without anemia (P < 0.05) [Table 3]. Deaths in hospital were also significant (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Laboratory findings in patients with HF

| Variables | Males | Females | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia (HB<10 g%) | 32% | 35% | 0.1 |

| HB at admission (g/dL) | 11.4 | 10.8 | 0.5 |

| HB at discharge (g/dL) | 9.2 | 9.6 | 0.4 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 136.2 | 137.8 | 0.12 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.24 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 1578 | 1521 | 0.5 |

P<0.05. BNP: brain natriuretic peptide

Table 3.

Characteristics in patients with or without anemia

| Variables | With anemia (32) | Without anemia (70) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 65.2 | 52.1 | 0.05 |

| Signs of congestion | 88% | 89% | 0.1 |

| Inotropic support | 72% | 71% | 0.5 |

| LVEF | 0.27±0.6 | 0.25±0.2 | 0.06 |

| Initial HB | 10.4±1 | 14.5±1.5 | 0.01 |

| Final HB | 10.5±1.5 | 13.2±2.5 | 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 28.2±3 | 56.2±4 | 0.01 |

| Initial hematocrit | 29.5±3 | 54.6±2 | 0.01 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 136.2 | 137.4 | 0.31 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.81 | 1.62 | 0.01 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 1564 | 1240 | 0.05 |

| Days in hospital | 37.8 | 32.6 | 0.2 |

| Deaths in hospital | 20% | 95 | 0.01 |

P>0.01

Discussion

Anemia is considered when there is a deficiency of RBCs or hemoglobin in the blood resulting in pallor. It results from excessive blood loss as in case of menstruation in females, gastrointestinal tract ulcers or colon cancer. Other causes such as the production of cytokines—IL 1.6 and 18, drugs such as the inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme, carvedilol, and angiotensin-I receptor blocker, used to treat HF can also cause anemia as they result in the inhibition of the erythropoietin production.[9] Research has shown that renal dysfunction, decrease in body mass index, old age, female gender, and left ventricular dysfunction are the factors that are linked with higher incidence of anemia.[10,11] The present study was conducted to access the presence of anemia in patients with advanced HF and compared the clinical characteristics of patients with anemia and without anemia.

We found that out of 102 patients of HF, 32 had anemia whereas 70 had not. 88% of anemic patients and 89% non-anemic patients showed signs of congestion. 72% anemic and 71% non anemic patients- needed inotropic support. Our results are in agreement with the study by Cardaso et al.[12] They included 99 patients with advanced HF. Anemia was seen in 34.3% of patients with HF whereas in our study it was present in 31.3%. They found that anemic patients were older (64.1 ± 15.6 years) in comparison with non-anemic patients (54.8 ± 12.9 years). In our study, we observed that mean age in anemic patients was 65.2 years and in non-anemic patients it was 52.1 years. Silva et al.[13] conducted a study to correlate anemia, renal failures, and HFs and found that anemia was present in 32% of cases. Groenveld[14] in their meta-analysis study found that 37.2% patients were suffering from anemia.

We observed that anemic patients had creatinine level of 1.81 mg/dL as compared to non-anemic patients who had 1.62 mg/dL. There was a significant difference between anemic and non-anemic patients. BNP level found to be statistical significant between anemic (1564 pg/mL) and non-anemic (1240 pg/mL) patients. Komajda et al.[15] in their study of prevalence of anemia in patients with congestive HF found that creatinine level was higher in anemic patients (1.9 ± 1 mg/dL) as compared to non-anemic patients (1.5 ± 1). BNP level was also higher (2,077.4 ± 1,979.4 vs1,212.56 ± 1,080.6 pg/mL in anemic and non-anemic patients).

Philipp et al. conducted a study to access the prevalence of anemia and its relationship to renal function, left ventricular function, and symptoms of HF. Out of a total number of 2941 patients, 238 patients (8.1%) had hemoglobin values <11 g/dL. There was a positive association of anemia with the symptoms of heart failure (HF) with a lowering of the median hemoglobin from 14.2 g/dL. There was no correlation of anemia with left ventricular function or any left ventricular parameters.[16]

Dunlay et al. examined two cohorts of Olmsted County residents with HF. The retrospective cohort included incident HF cases from 1979–2002 (n = 1063). The prospective cohort included active HF cases from 2003–2006 (n = 677). The prevalence of anemia was 40% in the retrospective and 53% in the prospective cohorts. Anemia prevalence increased by an estimated 16% between 1979 and 2002 (P = 0.008), and was higher in those with preserved (≥50%), vs reduced (<50%) ejection fraction (58% vs 48%, respectively, P < 0.001) from 2003 to 2006. In the prospective cohort, after adjustment for clinical characteristics, the HR (95% CI) for death were 3.07 (1.26–6.82) in those with hemoglobin ≥16 mg/dL and 2.39 (1.37–4.27) in those with hemoglobin <10 mg/dL using hemoglobin 14–16 mg/dL as the referent.[17]

Savarese G et al. conducted a study to compare the prevalence of, associations with, and prognostic role of anemia in HF across the ejection failure (EF) spectrum. Out of 49,985 patients with HF (anemia=34%), 23% had HFpEF (anemia=41%), 21% had heart failure with reduced mid range ejection fraction (HFmrEF) (anemia=35%) and 55% had HFpEF (anemia=32%). Higher EF was independently associated with higher likelihood of concomitant anemia. Anemia had adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) for mortality or HF hospitalization 1.24 (1.18-1.30) in HFpEF, 1.26 (1.19-1.34) in HFmrEF and 1.14 (1.10-1.19) in heart failure with reduction ejection fraction (HFrEF); pinteraction EF=0.003; and for mortality 1.28 (1.20-1.36) in HFpEF, 1.21 (1.13-1.29) in HFmrEF, and 1.30 (1.24-1.35) in HFrEF; pinteraction EF=0.22.[18]

Tisminetzky M et al. examined the impact of anemia and HF on in-hospital complications, and post-discharge outcomes in adults ≥65 years hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). The study population consisted of 3,863 patients ≥65 years hospitalized with AMI and were categorized into 4 groups based on the presence of previously diagnosed anemia (hemoglobin ≤10 mg/dL) and/or HF: Those without these conditions (n = 2,300), those with anemia only (n = 382), those with HF only (n = 837), and those with both conditions (n =344). Individuals who presented with both previously diagnosed conditions were at the greatest risk for experiencing adverse events. Patients who presented with HF only were at higher risk for developing several clinical complications during hospitalization, whereas those with anemia only were at slightly higher risk of being rehospitalized within 7-days of their index hospitalization.[19]

Abebe et al.[20] conducted a study to record incidence of anemia in HF patients and to relate clinical outcomes in patients with or without anemia. 375 patients were included with HF. There was higher prevalence of females (64.5%) than males. 41.9% patients had anemia. The level of creatinine, sodium, and hemoglobin showed a statistical significant difference between anemic and non-anemic patients.

We observed that etiology of HF was ischemia, high blood pressure, obesity, valvular heart disease, diabetes, and idiopathic. The most common cause among all was ischemia followed by idiopathic. Choi et al.[21] found ischemia as a leading cause of HF in 52.3% patients. They found that the mean LVEF was 38.5 ± 15.7% and 26.1% of the patients had preserved systolic function (LVEF ≥50%), which was more prevalent in the females (34.0% vs 18.4%, respectively, P < 0.001). Cardaso et al.[12] found ischemia in 29%, Chagas disease in 33%, valvular heart disease in 8%, alcohol consumption in 7% and high blood pressure in 17% cases as reason for HF.

We observed that age was the risk factor for HF in both anemic and non-anemic patients. The progress of anemic patients was worse than non-anemic patients. We assessed hemoglobin level and hematocrit value in all patients and found that iron deficiency as common factor. We found that even after fluid overload in most of the patients, there was no rise in hemoglobin and hematocrit value after compensation. This led to the finding that hemodilution was not main etiology of anemia in our cases.

Silva et al.[13] found that 33% of patients with anemia had deficiency of iron, folic acid, and vitamin B12. Nanas et al.[22] found iron deficiency as major cause of anemia after excluding patients with high creatinine levels (>3 mg/dL). We can suggest that anemia may result from iron deficiency, renal dysfunction and systemic inflammatory process of HF. Our results are in agreement with other studies.[23,24,25] Mester et al.[26] revealed that anemia and iron deficiency affect half of the CHF patients and they are linked with increased hospitalization rate, high mortality rate, poor quality of life and lower functional capacity. The limitation of the study is that it was a single-center study. The sample size was small. A large sample size may reveal different results.

Implications for clinical practice

The primary care physician is the first contact of a patient for the consultation of illness. Early diagnosis and a multi-disciplinary approach are key components of managing the anemia associated with HF. Increased awareness and research in this field have facilitated identification of risk factors and causation pathways. Certain therapies have shown a promise that needs evaluation in prospective clinical trials. Anemia is a common finding in patients with HF. The cause for anemia is multifactorial, with iron deficiency being the most common cause. Anemia with HF is an established predictor of morbidity and mortality. Iron deficiency in systolic HF, even without anemia, has been associated with increased mortality, increased hospitalizations, and decreased functional capacity and quality of life measures. Thus the early diagnosis of the anemia can serve as one of the indicators for HF.[27]

Conclusion

Anemia was seen in one-third of the patients with HF. Anemia was independent marker with poor prognosis. Anemic patients were older than non-anemic patients.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Okonko DO, Anker SD. Anemia in chronic heart failure: Pathogenetic mechanisms. J Card Fail. 2004;10(1 Suppl):5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Givertz MM, Colucci WS, Braunwald E. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007. Clinical aspects of heart failure: High-output failure; pulmonary edema; pp. 539–68. [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Meara E, Clayton T, McEntegart MB, McMurray JJ, Lang CC, Roger SD, et al. CHARM Committees and Investigators. Clinical correlates and consequences of anemia in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure: Results of the Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) Program. Circulation. 2006;113:986–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.582577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anand I, McMurray JJ, Whitmore J, Warren M, Pham A, McCamish MA, et al. Anemia and its relationship to clinical outcome in heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110:149–54. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000134279.79571.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witte KK, Desilva R, Chattopadhyay S, Ghosh J, Cleland JG, Clark AL, et al. Are hematinic deficiencies the cause of anemia in chronic heart failure? Am Heart J. 2004;147:924–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Means RT Jr. Advances in the anemia of chronic disease. Int J Hematol. 1999;70:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swedberg K, Young JB, Anand IS, Cheng S, Desai AS, Diaz R, et al. Treatment of anemia with darbepoetin alfa in systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1210–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand IS, Gupta P. Anemia and iron deficiency in heart failure. Current concepts and emerging therapies. Circulation. 2018;138:80–98. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.030099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ezekowitz JA, McAlister FA, Armstrong PW. Anemia is common in heart failure and is associated with poor outcomes. Insight from a cohort of 12.065 patients with new onset heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:223–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052622.51963.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young JB, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Gattis Stough W, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, et al. Relation of low hemoglobin and anemia morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure (Insight from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry) Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams KF Jr, Patterson JH, Oren RM, Mehra MR, O’Connor CM, Piña IL, et al. Prospective assessment of the occurrence of anemia in patients with heart failure: Results from the study of anemia in a heart failure population (STAMINA-HFP) registry. Am Heart J. 2009;157:926–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cardoso J, Brito MI, Ochiai ME, Novaes M, Berganin F, Thicon T, et al. Anemia in patients with advanced heart failure. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2010;95:524–9. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2010005000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Silva R, Rigby AS, Witte KK, Nikitin NP, Tin L, Goode K, et al. Anemia, renal dysfunction, and their interaction in patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:391–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groenveld HF, Januzzi JL, Damanan K, van Wijngaarden J, Hillege HL, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Anemia and mortality in heart failure patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:818–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komajda M. Prevalence of anemia in patients with chronic heart failure and their clinical characteristics. J Card Fail. 2004;10:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philipp S, Ollmann H, Schink T, Dietz R, Luft FC, Willenbrock R. The impact of anaemia and kidney function in congestive heart failure and preserved systolic function. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:915–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Redfield MM, Killian JM, Roger VL. Anemia and heart failure: A community study. Am J Med. 2008;121:726–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savarese G, Jonsson A, Hallberg AC, Dahlstrom U, Edner M, Lund LH. Prevalence of, associations with, and prognostic role of anemia in heart failure across the ejection fraction spectrum. Int J Cardiol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.08.049. pii: S0167-5273 (19) 31354-3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard. 2019.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tisminetzky M, Gurwitz JH, Miozzo R, Gore JM, Lessard D, Yarzebski J, et al. Characteristics, management, and short-term outcomes of adults≥65 years hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction with prior anemia and heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124:1327–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abebe TB, Gebreyohannes EA, Bhagavathula AS, Tefera TG, Abegaz TM. Anemia in severe heart failure patients: Does it predict prognosis? BMC Cardiovas Disord. 2017;17:248. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0680-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi DJ, Han S, Jeon ES, Cho MC, Kim JJ, Yoo BS, et al. Characteristics, outcomes and predictors of long-term mortality for patients hospitalized for acute heart failure: A report from the Korean heart failure registry. Korean Circ J. 2011;41:363–71. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2011.41.7.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nanas JN, Matsouka C, Karageorgopoulos D, Leonti A, Tsolakis E, Drakos SG, et al. Etiology of anemia in patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2485–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He SW, Wang LX. The impact of anemia on the prognosis of chronic heart failure: A meta-analysis and systemic review. Congest Heart Fail. 2009;15:123–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2008.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolger AP, Barlett FR, Penston HS, O’Leary J, Pollock N, Kaprielian R, et al. Intravenous iron alone for the treatment of anemia in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1225–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ralli S, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Relationship between anemia, cardiac troponin I, and B-type natriuretic peptide levels and mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. Am Heart J. 2005;150:1220–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mester A, Mitre A, Lázár E, Benedek I, Jr, Kéri J, Pakucs A, et al. Anemia and iron deficiency in heart failure- Clinical update. J Interdiscip Med. 2017;2:308–11. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zusmana O, Itzhaki Ben Zadoka O, Gafter-Gvilib A. Management of iron deficiency in heart failure. Acta Haematol. 2019;142:51–6. doi: 10.1159/000496822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]