Abstract

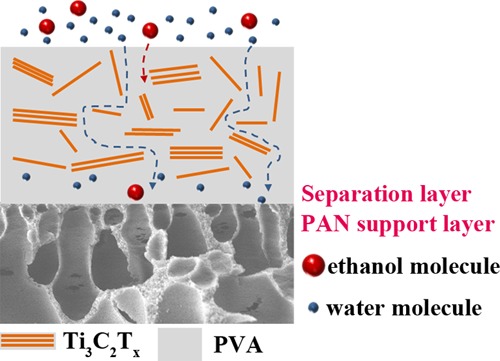

In this paper, PVA/Ti3C2Tx mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) were prepared by mixing the synthesized Ti3C2Tx with the PVA matrix, and the pervaporation (PV) performance of the ethanol–water binary system was tested. The morphology, structural properties, and surface characteristics of the membranes were investigated by scanning electron microscopy, atomic force microscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, degree of swelling, and water contact angle. The PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs exhibit excellent compatibility and swelling resistance. Moreover the effects of the Ti3C2Tx filling level, feed concentration, and operating temperature on the ethanol dehydration performance were systematically studied. The results demonstrated that the separation factor of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs was significantly increased because of Ti3C2Tx promoting the cross-linking density of the membrane. Specifically, the membrane showed the best PV performance when Ti3C2Tx loading was 3.0 wt %, achieving a separation factor of 2585 and a suitable total flux of 0.074 kg/m2 h for separating 93 wt % ethanol solution at 37 °C.

1. Introduction

Fuel ethanol,1,2 as a renewable bioliquid fuel to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gases, has been promoted and used in many countries and regions around the world in recent years. With the severe environmental pollution and the exhaustion of resources such as petroleum, fuel ethanol has grown into one of the considerable alternative energy sources. One of the main production technologies of fuel ethanol is the biofermentation method,3 which produces 6–10 wt % ethanol and then obtains 95 wt % industrial ethanol by distillation. To acquire absolute ethanol, particular methods must be adopted. Different from traditional separation methods, pervaporation (PV) technology4 breaks the restriction of the vapor–liquid equilibrium and shows obvious advantages in the separation of liquid mixtures of azeotrope or close boiling compounds: energy conservation, environmental protection, less space, and easy for industrial scale-up.5,6 The industrial application of the PV process has been widely recognized in organic solvent dehydration.7,8 Many hydrophilic polymer membranes such as chitosan (CS),9 poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA),10 sodium alginate (SA),11 and so forth. have been investigated for the ethanol–water binary system. PVA possesses extraordinary physicochemical properties and can maintain its properties within long-term operation, which is suitable for providing basic membrane materials for organic solvent dehydration.12 In 1982, the German GFT Company was the first to make breakthroughs in the industrial application of PV, introducing commercial PVA/poly(acrylonitrile) (PVA/PAN) composite membranes. However, a large number of OH groups in the PVA molecular chain result in strong hydrophilicity. Untreated PVA tends to swelling in aqueous solution, and the defects impair the separation performance of the PVA membrane.13,14 The German GFT Company published the PV performance of the GFT commercial membrane: for 80 wt % ethanol aqueous mixture of the feed liquid, the separation factor was 100–200 and the total flux was 1.0 kg/m2 h at 80 °C. In addition, the separation factor of the GFT-1510/2510 commercial membrane (95 wt % ethanol concentration) was 258 and the corresponding total flux was 0.6 kg/m2 h.15 Although the pristine PVA membrane has achieved industrial applications, its separation factor is still restricted. In order to combat this, many modification methods such as cross-linking,16 grafting,17 and blending13 have been employed. Among them, doping two dimensional (2D) materials,18 such as graphene,19 graphene oxide (GO),19,20 carbon nitride (C3N4),21,22 metal–organic frameworks (MOFs),23 and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), has attracted the attention of researchers.24 In the work of Wu et al.,25 various UiO membranes were fabricated by altering the organic linkers and doped in the PVA matrix for separation of 90 wt % ethanol solution. The mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) displayed obvious anti “trade-off” effects: for the UiO-66-(OH)2/PVA-1.0 MMM, the total flux and separation factor were increased by 16 and 14%, respectively. Zhang and Wang26 fabricated PVA/ZIF-8-NH2 membranes for ethanol dehydration. The MMMs exhibited enhanced PV performance, which was due to the increased hydrophilicity of ZIF-8-NH2 with the PVA matrix. The total flux and separation factor of PVA/ZIF-8-NH2 MMMs could reach to 0.13 kg/m2 h and 201, respectively, at 40 °C.

2D materials27 with atomic thickness and micrometer lateral dimensions have been widely used to develop membranes with high separation performance. Moreover, they have mechanical properties, thermal stability, excellent layered structure, and 2D nanochannels, making the two-dimensional material separation membrane have extraordinary permeability.28−30 As a new member of the 2D material family, transition metal carbides (MXenes) were discovered by Gogotsi and Barsoum in 2011. MXenes31 have the formula Mn+1XnTx, where n is 1, 2, or 3, M is an early transition metal, X is C and/or N, and T is the OH and/or O group. Among them, the formula of MAX phases (the precursors of MXenes) is Mn+1AXn, where A stands for an A-group element (such as Al and Si).32 One of the most representative MAX materials is Ti3AlC2. Here, Al was extracted from Ti3AlC231,33 and a two-dimensional material called Ti3C2Tx Mxene was prepared. The hydrophilic, rigorous layered structures and extremely short water molecule transport channel of Ti3C2Tx have attracted the attention of researchers in the field of membrane separation.34−37 Liu et al.37 first prepared ultrathin Ti3C2Tx membranes for desalination by assembling the Ti3C2Tx nanomaterial. The selected Ti3C2Tx membrane showed high water flux and salt rejection. In addition, this Ti3C2Tx assembly membrane could maintain 100 h of PV desalination. Wu et al.38 fabricated 2 μm-thick MXene membranes and applied it in ethanol dehydration. At room temperature and 5 wt % H2O concentration, the total flux of the MXene membrane was 263 g m–2 h–1 and the separation factor was 135. At present, the Ti3C2Tx-based membrane has achieved some research results in terms of water treatment and gas separation.39,40 Moreover, research studies on dehydration of organic solvents are still in progress.

Herein, for the first time, 2D Ti3C2Tx was embedded in the PVA matrix, and PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs was successfully prepared. Various membranes were labeled PVA/Ti3C2Tx-0.0, PVA/Ti3C2Tx-0.5, PVA/Ti3C2Tx-1.0, PVA/Ti3C2Tx-2.0, PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0, and PVA/Ti3C2Tx-4.0. The structure and physicochemical properties of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs were analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS), atomic force microscopy (AFM), attenuated total reflectance-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), water contact angle (WCA), and degree of swelling (DS). In addition, the ethanol–water binary system was used to evaluate the PV performance of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Morphology

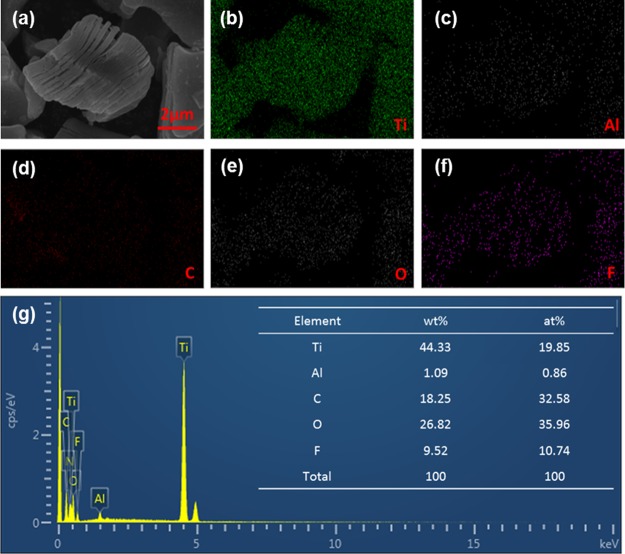

The SEM morphology and EDS results of the Ti3C2Tx powder are shown in Figure 1. The lateral dimension of Ti3C2Tx was about 5 μm and showed a typical stacked layered structure like “accordion”, which enabled Ti3C2Tx advantageous for arranging 2D nanochannels in the PVA matrix.41 It can be seen from the results of EDS analysis that Ti3C2Tx mainly contained a large amount of Ti elements and C elements, and the presence of small quantities of Al elements may be because HF did not completely etch Al elements. In addition, 26.8 wt % of the O element and 9.5 wt % of the F element were observed, indicating that Ti3C2Tx contained a large amount of oxygen functional groups, which was advantageous for improving the hydrophilicity of the material.

Figure 1.

SEM images (a) and EDS results (b–g) of the Ti3C2Tx powder.

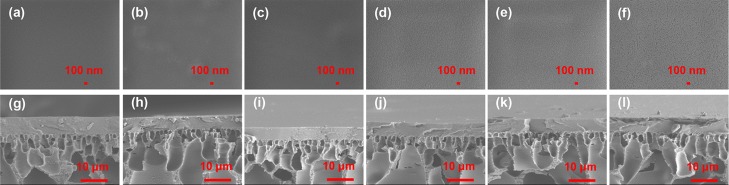

The surface and cross-sectional view of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs are shown in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2a–f, the surface image of the pristine PVA membrane was smooth and flat. The PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMM surface with slight fluctuations looked dense without any visible defects. It indicates that Ti3C2Tx has good compatibility with PVA, probably because of the interactions between the oxygen functional groups of Ti3C2Tx and the PVA chain. In addition, it can be seen from Figure 3a that the surface of PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM is loaded with Ti3C2Tx particles. Figure 2g–l showed the cross-sectional structure of the membranes, and the thickness of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs was about 6 μm. Moreover, the separation layer was firmly bonded on the PAN support layer.

Figure 2.

SEM surface view (a–f) and cross-sectional structure (g–l) of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs with different Ti3C2Tx fillings: (a,g) 0.0; (b,h) 0.5; (c,i) 1.0; (d,j) 2.0; (e,k) 3.0; and (f,l) 4.0 wt %.

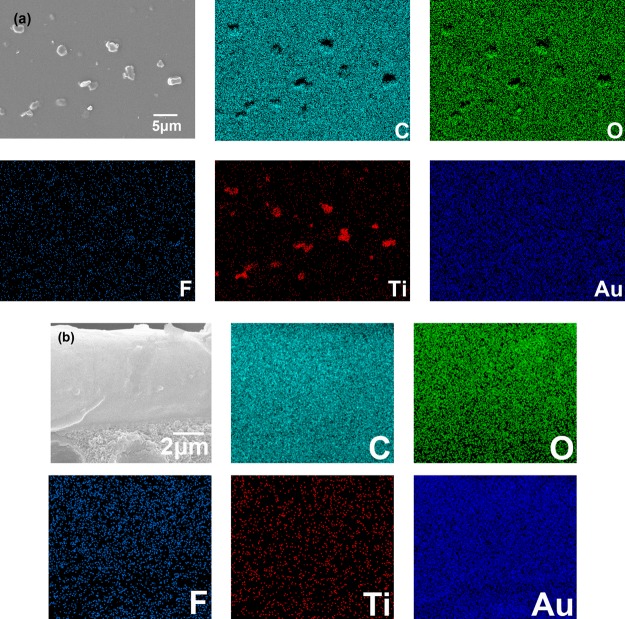

Figure 3.

EDS results of PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMMs: (a) surface view and (b) cross-sectional structure.

The EDS diagram of surface morphology and cross-sectional structure of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM are shown in Figure 3. It can be seen that Ti elements and F elements are substantially uniformly distributed on the surface and cross section of the membrane, indicating that the distribution of Ti3C2Tx in the PVA matrix is relatively uniform. Among them, the gold element is distributed by spraying gold during the sample preparation process.

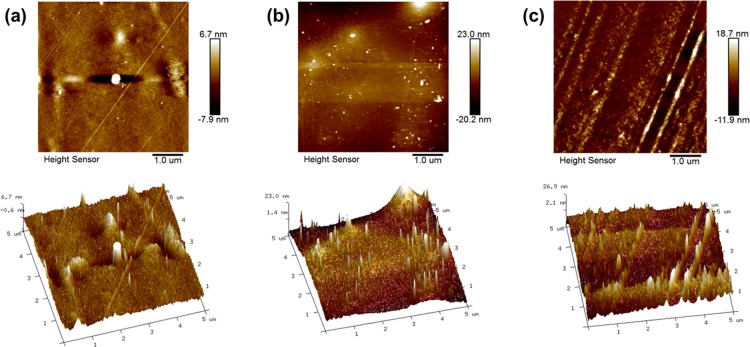

To further research the surface structure of the MMMs, topography images and the surface roughness values of the MMMs were determined with AFM (Figure 4). The roughness values (Ra and Rq) of the membrane surface are shown in Table 1. The roughness increased with the increase of Ti3C2Tx addition, which may be due to a higher Ti3C2Tx filling that leads to a larger particle size with more chance of agglomeration on the membrane surface.

Figure 4.

AFM images of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs with different mass fractions of Ti3C2Tx filling: (a) 0.0; (b) 1.0; and (c) 3.0 wt %.

Table 1. Surface Roughness of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs.

| surface roughness | PVA/Ti3C2Tx-0.0 | PVA/Ti3C2Tx-1.0 | PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ra (nm) | 1.99 | 4.02 | 4.87 |

| Rq (nm) | 2.58 | 5.49 | 6.31 |

2.2. ATR-FTIR and XRD Patterns of the Membranes

The ATR-FTIR patterns of Ti3C2Tx powder, Ti3AlC2 powder, and PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs are shown in Figure 5. As can be seen from Figure 5a, Ti3AlC2 is substantially free of any functional groups, whereas Ti3C2Tx mainly comprises OH groups and C–O–C groups, which is consistent with previous articles.33 In Figure 5b, the broad absorption peak at 3267 cm–1 represented the OH groups and the peak intensity of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs at 3267 cm–1 decreased with increasing Ti3C2Tx filling. The absorption bands at 1710 and 1234 cm–1 correspond to C=O and C–O groups, respectively. Moreover, the characteristic peak formed at 1090 cm–1 was related to the asymmetric stretching vibration of C–O–C groups. According to a previous study,42 the cross-linking density of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs could be semi-quantitatively analyzed by the FT-IR peak intensity of C–O–C groups (1090 cm–1) and OH group (3267 cm–1) ratio (H1090/H3267). Table 2 demonstrated that the H1090/H3267 increased with increasing Ti3C2Tx filling. It further indicates that the cross-linking density of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs is positively correlated with the amount of Ti3C2Tx filling. The ATR-FTIR spectra showed that Ti3C2Tx promoted the cross-linking reaction of PVA, and Ti3C2Tx was well incorporated into the PVA matrix.

Figure 5.

FT-IR spectra of (a) Ti3C2Tx, Ti3AlC2, and (b) PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs.

Table 2. Peak Intensity Ratio of 1090 and 3267 cm–1 in the FT-IR Spectra of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs.

| membrane | PVA/Ti3C2Tx-0.0 | PVA/Ti3C2Tx-0.5 | PVA/Ti3C2Tx-1.0 | PVA/Ti3C2Tx-2.0 | PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 | PVA/Ti3C2Tx-4.0 |

| H1090/H3267 | 1.56 | 1.57 | 1.71 | 1.82 | 1.84 | 2.11 |

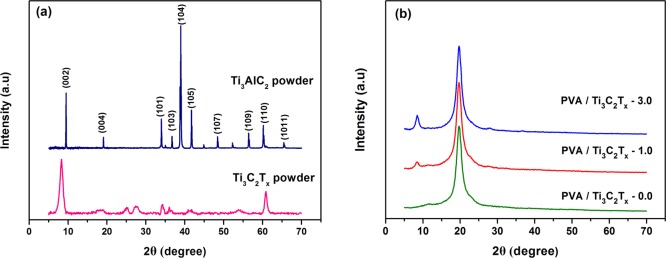

The Ti3AlC2 powder, Ti3C2Tx powder, and PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs were further studied by XRD. Figure 6a presented the XRD patterns of Ti3C2Tx and Ti3AlC2 powders. Ti3C2Tx powders were transferred to a lower angle at the (002) peak than Ti3AlC2, and Ti3C2Tx has no strong diffraction peak at 2θ = 39°, which means that most of the Al elements on Ti3AlC2 were etched away and Ti3C2Tx was successfully synthesized. The same conclusion appeared in previous reports.34,37 In Figure 6b, a strong diffraction peak at 2θ = 19.7° (d-spacing of 4.5 Å) was a typical lattice of PVA, indicating that PVA is a semicrystalline polymer. The strong diffraction peaks of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs at 2θ = 19.7° and 2θ = 8.4° represented the main characteristic peaks of PVA and Ti3C2Tx, respectively. In addition, with the increase of Ti3C2Tx filling, the peak intensity at 2θ = 8.4° increased and the peak intensity at 2θ = 19.7° slightly decreased.

Figure 6.

XRD patterns of Ti3AlC2 powder, Ti3C2Tx powder, (a) and PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs (b).

2.3. Hydrophilic and DS

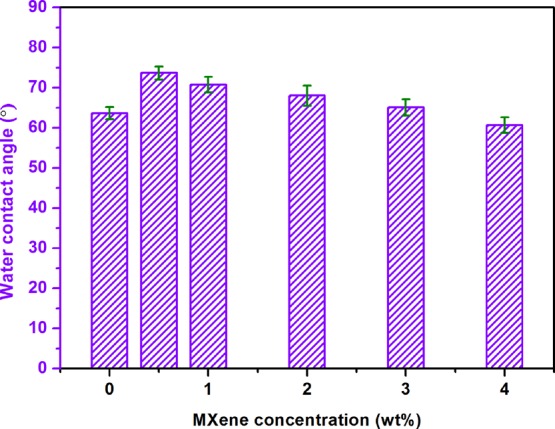

The hydrophilicity of the membrane surface is an essential property for PV. Figure 7 shows the WCAs of different membranes. With the increase of Ti3C2Tx, the small decrease in contact angle indicates that the hydrophilicity is enhanced. Although with the increase of Ti3C2Tx addition, the hydroxyl group is decreased, from Figure 4 and Table 1, we can see that the roughness is increased, and the combination of the two factors resulted in a small decrease in the contact angle.

Figure 7.

WCA of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs with different amounts of Ti3C2Tx filling.

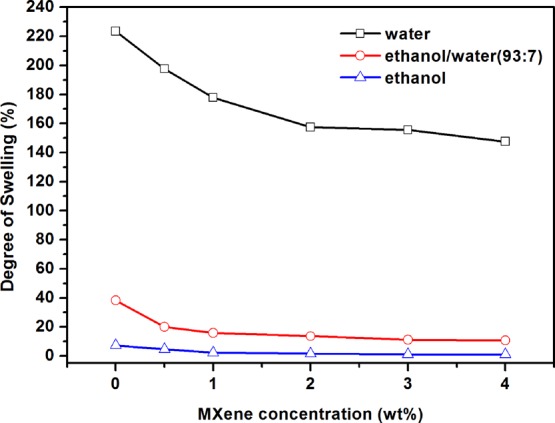

The DS of the experiment was tested in water, pure ethanol, and 93 wt % ethanol aqueous solution at constant temperature. The DS formula is as the following equation

| 1 |

where WA and WB are the mass of the wet and dry membrane samples (g), respectively. The DS of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs decreased with the increase of Ti3C2Tx filling, as shown in Figure 8. The possible reason can be described that the interaction between Ti3C2Tx and the PVA matrix increases the cross-linking density of the membrane, which limits the movement of PVA molecular chains. In addition, the decrease of hydrophilicity of MMMs (Figure 7) results in a decrease of affinity for water molecules.43 In general, Ti3C2Tx has good mechanical properties and swelling resistance,44 so the addition of Ti3C2Tx inhibited the swelling of the PVA membrane.

Figure 8.

DS of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs with different Ti3C2Tx loadings.

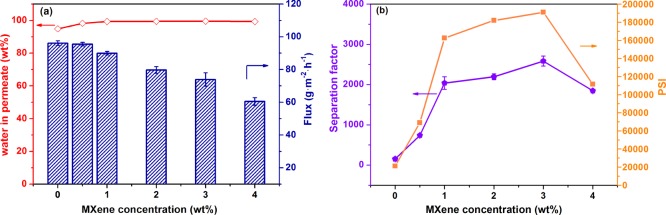

2.4. PV Performance for the Ethanol–Water Binary System

The PV performance of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs for the ethanol–water binary system was evaluated. Ti3C2Tx filling levels have a significant influence on the separation performance of the membrane. First, the effect of Ti3C2Tx filling was studied at 37 °C and 93 wt % ethanol concentration. The total flux of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs decreased with increasing Ti3C2Tx filling, as shown in Figure 9a. We can explain that the crystallinity of PVA membranes was not significantly improved (Figure 6) and the hydrophilicity of the membrane surface was declined (Figure 7) from the preceding analysis, which makes water molecules more difficult to enter the membranes. On the other hand, the resistance of water components passing through the membrane increases, attributed to the increase in the cross-linking density and aggregation of Ti3C2Tx, so the water flux decreased. The total flux depends on the water flux, so the total flux decreased. In addition, it can be seen that the water content in the permeate of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx membranes exceeded 98.3 wt %. According to Figure 9b, the optimum value of the separation factor was 2585 when the Ti3C2Tx filling was 3.0 wt %. Moreover, the separation factor increased when the Ti3C2Tx loading increased from 0.0 to 3.0 wt %, which may be owing to the enhanced cross-linking density of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs, which led to the denser separation layer. The infrared analysis and DS test side demonstrated that the cross-linking density of the membrane increased after the addition of Ti3C2Tx. It showed that the addition of Ti3C2Tx could improve the separation factor of the PVA membrane. However, when the amount of Ti3C2Tx filling exceeded 3.0 wt %, the separation factor decreased, which may be due to the fact that Ti3C2Tx loading reached the saturation limit, and higher than the concentration value, and agglomeration of Ti3C2Tx occured, resulting in defects in the membrane.41,43Table 3 showed the effect of Ti3C2Tx loading on the permeability and selectivity. Water permeability decreased with the increase of loading amount of Ti3C2Tx, and ethanol permeability first decreased and then increased. When the loading amount of Ti3C2Tx was 3.0 wt %, ethanol permeability was the lowest. The PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM had the highest selectivity based on the change of water permeability and ethanol permeability, and this was consistent with the variation of the separation factor. The pervaporation separation index (PSI) is defined as the product of the total flux and separation factor and is used to characterize the PV performance of the membrane. PSI reached the highest value when the Ti3C2Tx filling was 3.0 wt %. Herein, 3.0 wt % Ti3C2Tx was the best filling amount for ethanol dehydration.

Figure 9.

PV performance of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs. Total flux and water in the permeate (a) and separation factor and PSI (b) for membranes at different Ti3C2Tx fillings.

Table 3. Effect of Ti3C2Tx Loading on the Permeability and Selectivity.

| Ti3C2Tx loading (wt %) | water permeability (106 g/m h kPa) | ethanol permeability (106 g/m h kPa) | total permeability (106 g/m h kPa) | selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 281.42 | 2.27 | 283.69 | 124.2 |

| 0.5 | 273.30 | 0.76 | 274.06 | 360.6 |

| 1.0 | 267.95 | 0.26 | 268.21 | 1006.4 |

| 2.0 | 237.63 | 0.21 | 237.84 | 1093.2 |

| 3.0 | 199.53 | 0.15 | 199.68 | 1298.3 |

| 4.0 | 160.01 | 0.20 | 160.21 | 826.5 |

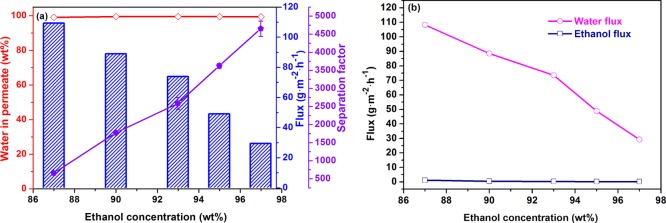

Based on the optimal Ti3C2Tx filling, we evaluated the effect of ethanol concentration in the feed liquid for the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM. The effect of the ethanol content in the feed solution on the PV performance at 37 °C is shown in Figure 10. The water concentration in the feed liquid directly affects the adsorption behavior of each component on the membrane surface. As shown in Figure 10a, when the ethanol concentration in the feed liquid increased from 87 to 97 wt %, the total flux decreased from 0.11 to 0.03 kg/m2 h. This phenomenon was described in early work.45 When the water content in the feed decreases, the selective interaction between water molecules and membranes decreases, which reduces the driving forces of the water molecules. Furthermore, from the result of the DS of the MMMs (Figure 8), at higher ethanol concentrations, the expansion degree of the membrane was less, which reduced the free volume of the membrane. Therefore, the transport resistance of ethanol and water molecules increases, resulting in the decrease of total flux. It can be concluded from Figure 10b that the water flux was much higher than the ethanol flux, and the trend was close to the total flux, so the total flux was determined by the water flux. The information presented in Figure 10a also included that the separation factor increased from 654 to 4652 with the increase of ethanol concentration. This is mainly due to the decreases in the DS of the membrane, which weakens the chain movement of the polymer. Because of the large molecular diameter of ethanol and the difficulty of passing ethanol through the membrane, the adsorption selectivity of the membrane to water increases, resulting in an increase in the separation factor. At different feed concentrations, the water content in the permeate of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM exceeded 99 wt % (Figure 10a). The permeability and selectivity of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM at different ethanol concentrations in the feed liquid, as shown in Table 4, water permeability, and ethanol permeability increased with increasing ethanol concentration. The reason is that the DS of the membrane decreased with a decrease in water content, the free volume is reduced, and the diffusion of the components is limited.25 In addition, the dissolution degree of the membrane is decreased, and then, the driving force of the molecules is reduced.39 It is worth noting that the change in permeability is not significant, but the selectivity is significantly increased.

Figure 10.

PV performance of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM. Total flux, water in permeates, and separation factor (a) and water flux and ethanol flux (b) for membranes at different feed concentrations.

Table 4. Effect of Ethanol Concentration on the Permeability and Selectivity of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM.

| ethanol concentration (wt %) | water permeability (106 g/m h kPa) | ethanol permeability (106 g/m h kPa) | total permeability (106 g/m h kPa) | selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 87 | 208.34 | 0.55 | 208.89 | 378.3 |

| 90 | 202.42 | 0.23 | 202.65 | 900.4 |

| 93 | 199.53 | 0.16 | 199.68 | 1298.3 |

| 95 | 196.02 | 0.10 | 196.12 | 1803.1 |

| 97 | 194.92 | 0.09 | 195.01 | 2304.2 |

The influence of operation temperature on PV performance is special. Figure 11 showed the effect of operating temperature on the PV performance of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs at 93 wt % ethanol concentration. All of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs showed significant enhancement in the total flux with increasing temperature, as shown in Figure 11a.46 We attribute this phenomenon to two reasons: first, at high feed temperatures, free diffusion of ethanol and water molecules intensifies, which increases the free volume of molecules, and the activity of polymer segments promotes the increase of DS. Second, the vapor pressure on the feed side increases with increasing temperature, leading to an increase in the mass transfer driving force of the membrane. Moreover, as seen in Figure 11b, the water flux and ethanol flux of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM both increased with increasing temperature. Therefore, the total flux increased. The activation energies of water and ethanol were obtained using the Arrhenius diagram (Figure 11c). The variation of the permeation flux of each component follows the following equation

| 2 |

where J is each component flux (kg/m2 h), J0 is the pre-exponential factor, R is the gas constant (kJ/mol K), Ep is the activation energy (kJ/mol), and T is the temperature. The activation energy of ethanol and water were 79.47 and 50.04 kJ/mol, respectively. The much higher ethanol activation energy indicated the higher temperature sensitivity of ethanol permeation over water permeation, and the ethanol flux tends to increase faster than that of water when the feed temperature increased. As shown in Figure 11d, the separation factor of all the PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs decreased with increasing temperature, which was similar to previously reported dense PV membranes.41,47 The reason was as follows: the free volume of molecules increases with increasing feed temperature, the permeation resistance of the ethanol molecules decreases, and furthermore, the penetration rate of ethanol exceeds the penetration rate of water. The permeability and selectivity of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM at different operating temperatures are shown in Table 5. It can be observed that the water permeability and the ethanol permeability both increase with increasing temperature, and the increase in temperature promotes the diffusion process of the components, indicating that this is an endothermic process.48 It is consistent with the trend of flux with temperature. The effect of temperature on permeability was described by the Arrhenius formula (eq 3)

| 3 |

where P is each component permeability (106 g/m h kPa), P0 is the pre-exponential factor, R is the gas constant (J/mol K), Ea is the activation energy (kJ/mol), and T is the temperature (K). Moreover, the permeability activation energies of water and ethanol are listed in Table 5. The smaller the apparent activation energy, the smaller the energy barrier of the molecule through the membrane,48 where EP,water is less than EP,ethanol, indicating that water permeability is more susceptible to temperature changes. In addition, because water permeability and ethanol permeability increase with increasing temperature, the selectivity of the membrane is decreased.25 In addition, the water content in permeate of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM exceeded 99.5 wt % at 37 °C.

Figure 11.

Total flux (a) and separation factor (d) of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs; water flux and ethanol flux (b), Arrhenius plots for water and ethanol flux (c), and water in permeates (d) of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 membrane under varied temperature.

Table 5. Effect of Temperature on the Permeability and Selectivity of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM.

| temperature (°C) | water permeability (106 g/m h kPa) | ethanol permeability (106 g/m h kPa) | total permeability (106 g/m h kPa) | selectivity | EP,water (kJ/mol) | EP,ethanol (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37 | 199.53 | 0.15 | 199.68 | 1298.3 | 15.5 | 41.5 |

| 45 | 206.93 | 0.22 | 207.15 | 921.9 | ||

| 53 | 220.27 | 0.33 | 220.60 | 661.5 | ||

| 61 | 264.42 | 0.49 | 264.91 | 536.6 | ||

| 69 | 300.56 | 0.68 | 301.24 | 441.4 |

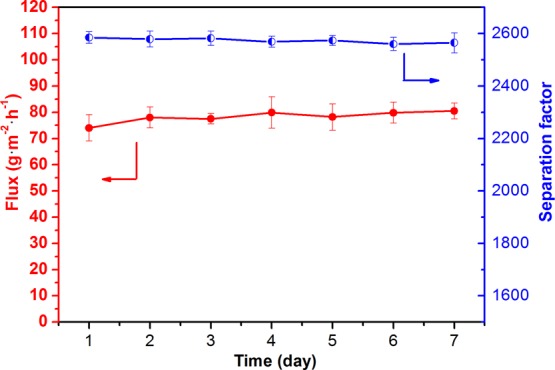

Figure 12 investigates the effect of operating time on the PV performance of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM. It can be seen that during continuous dehydration of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM at 37 °C and the 93 wt % ethanol–water binary mixture for about 7 days, the permeate flux and separation factor are relatively stable. It shows that the PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMM can operate stably for a long time.

Figure 12.

Long-term stability of the PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM under 37 °C and 93 wt % ethanol concentration.

Table 6 listed the PV performance of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs for ethanol dehydration compared with reported membranes.21,26,43,49−56 As can be seen, the prepared PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs exhibited a higher separation factor than most PVA-based membranes. It is indicated that loading Ti3C2Tx into polymer membranes has prospects.

Table 6. PV Performance of PVA-Based Membranes for the Ethanol–Water Binary Systema.

| membr. | temp. (°C) | water content (wt %) | J (kg/m2 h) | α | refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA/C3N4 | 75 | 10 | 6.33 | 30.7 | (21) |

| PVA/ZIF-8-NH2 | 40 | 15 | 0.16 | 148 | (26) |

| PVA/ZIF-90 | 30 | 10 | 0.27 | 1379 | (43) |

| PVA/Fe-DA | 30 | 10 | 0.99 | 2980 | (49) |

| PVA/H-ZSM5 | 30 | 15 | 0.18 | 46 | (50) |

| PVA/CF-TSA | 50 | 30 | 0.13 | 775 | (51) |

| PVA/NaY | 60 | 20 | 0.30 | 450 | (52) |

| PVA/SA | 30 | 10 | ∼0.35 | 25,000 | (53) |

| PA/SDS-clay | 25 | 10 | 12.0 | 0.28 | (54) |

| SA/MoS2 | 77 | 10 | 1.84 | 1229 | (55) |

| CS/siloxane | 25 | 10 | 0.47 | 2182 | (56) |

| PVA | 37 | 7 | 0.096 | 152 | this work |

| PVA/Ti3C2Tx | 37 | 7 | 0.074 | 2585 | this work |

C3N4, carbon nitride; ZIF, zeolite imidazolate framework; Fe-DA, iron-dopamine nanoparticles; CF, carboxy fullerene; TSA, p-toluene sulfonic acid; ZSM, molecular sieve; NaY, molecular sieve; SA, sodium alginate; PA, polyamide; MoS2, molybdenum disulphide; CS, chitosan.

3. Conclusions

In this study, the novel two-dimensional material, Ti3C2Tx, was used as an inorganic filler to prepare PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs. GA and PAN ultrafiltration membranes were used as cross-linking agents and the support layer, respectively. The results showed that Ti3C2Tx could be uniformly dispersed in the PVA matrix, and they had excellent compatibility. In addition, PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs exhibited excellent mechanical properties and swelling resistance. PV performance results showed that loading Ti3C2Tx in the PVA matrix significantly improved the separation factor of PVA membranes, but the total flux of PVA membranes decreased because of the enhanced cross-linking density and the weakened hydrophilicity of the membrane surface. The PVA/Ti3C2Tx-3.0 MMM had the best PV performance at 37 °C and 93 wt % ethanol solution, and the separation factor was 2585, which was 17 times higher than that of the pristine PVA membrane and with an acceptable permeation flux of 0.074 kg/m2 h. When the concentration of ethanol decreased and the feed temperature increased, the separation factor decreased and the total flux increased significantly, which was consistent with the typical regular of polymer membranes. The newly developed PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs have great potential for membrane separation applications, which provide some reference for the application of Ti3C2Tx in PV.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

PVA-124 was purchased from Xilong Chemical Co., Ltd. (Guangdong, China). Lithium fluoride (LiF, >99.9%) was supplied by Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Hydrochloric acid (HCl, AR) was from Beijing Chemical Works (Beijing, China). Glutaraldehyde (GA, 50%) was obtained from Tianjin Guangfu Fine Chemical Research Institute. (Tianjin, China). Glacial acetic acid (HAc, AR) and ethanol (AR) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

4.2. Synthesis of Ti3C2Tx Powders

LiF and HCl were used as milder etchants to replace HF, which were similar to previous research.31,33 The procedure was as follows: 1.98 g of LiF was slowly added to 6 M HCl solution (30 mL). After magnetic stirring for 1 h, 3 g of Ti3AlC2 powder was slowly added to the solution, and then, the mixture was held at 40 °C for 45 h and centrifuged with deionized water until the supernatant reached neutrality. Then, the black powder was dispersed in deionized water and sonicated for 1 h. Thereafter, the solution was centrifuged for 1 h to remove large particles. After decantation, the black Ti3C2Tx colloidal supernatants were obtained and dried in a vacuum oven.

4.3. Fabrication of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs

First, 8 g of PVA powders was dissolved in 2 wt % HAc solution (92 g) and stirred for 1 h at 90 °C, and then, the insoluble large particles were filtered off. An amount of Ti3C2Tx powder was dispersed in deionized water and sonicated for 1 h. Moreover, the abovementioned solutions were mixed and sonicated for 0.5 h to form uniform dispersions. GA (2 wt %) was added as a cross-linking agent to prepare the casting solution. Next, the casting solution was degassed by vacuum and poured onto the PAN ultrafiltration membranes, and solvents evaporate in a fume hood for 12 h. Finally, PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs were prepared by cross-linking for 2 h in an electric drying oven at 90 °C.

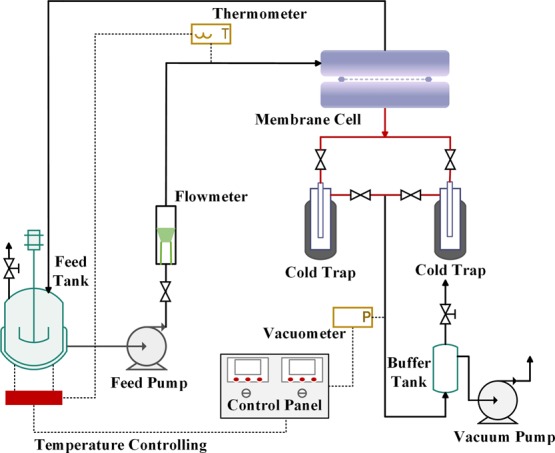

4.4. Evaluation of the PV Performance Test

The schematic diagram of the self-designed PV apparatus is illustrated in Figure 13. Among them, the effective area of the membrane was 2.2 × 10–3 m2. The pump delivers the feed liquid to the membrane cell. The vacuum on the permeate side is formed using a vacuum pump, and the minimum absolute pressure can reach 0.2 kPa. The permeation mixture was collected in the cold trap made of liquid nitrogen bath, and the contents of upstream feed solution and downstream permeate were analyzed by gas chromatography (Shimadzu, GC-14C, Japan).

Figure 13.

Schematic illustration of the PV evaluation apparatus.

The total flux (J) and separation factor (α) were two key indicators of PV performances, which are defined as the following equations

| 4 |

| 5 |

where J is the total flux (kg/m2 h); Q is the weight of the permeation component (g); A is the effective area of the membrane (m2); t is the time (h); α represents the separation factor; Y is the mass fraction of components in the permeate liquid (wt %); X is the mass fraction of components in the feed liquid (wt %); and i and j stand for water and ethanol, respectively.

In addition, the permeability (Pi) and the selectivity (βP) are defined as eqs 6 and 7

| 6 |

| 7 |

where Pi is each component permeability (106 g/m h kPa), Ji is each component flux (kg/m2 h), l is the thickness of the separation layer (m), x and y stand for the molar fractions of the component in the feed liquid and the permeate liquid (%), respectively, γi and Pis (kPa) are the activity coefficients of feed mixtures and saturated vapor pressures obtained using Aspen Plus software, PP is the permeate side pressure (kPa), βP is the selectivity, and PW and PE are water permeability and ethanol permeability (106 g/m h kPa), respectively.

4.5. Characterization

The morphology of powder and membranes was characterized by SEM (JSM7401F, Japan) and EDS. AFM (SPA-400, Japan) was used to characterize the morphology of membranes. The structural properties of PVA/Ti3C2Tx MMMs were studied with ATR-FTIR (Bruker TENSOR 27). The diffraction patterns and crystalline phases of membranes (remove the PAN ultrafiltration membrane) were researched by XRD (Bruker D8 ADVANCE, Germany). The Ti3AlC2 and Ti3C2Tx powders were also characterized. The hydrophilicity of membranes was experimented by the WCA (Model PV-DP). The DS test was also performed.

Acknowledgments

This work has been financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 21736001, 21776153, and 21576150).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Kumar S.; Singh N.; Prasad R. Anhydrous ethanol: A renewable source of energy. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 1830–1844. 10.1016/j.rser.2010.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona C. A.; Sánchez Ó. J. Fuel ethanol production: Process design trends and integration opportunities. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 2415–2457. 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava N.; Rawat R.; Singh Oberoi H.; Ramteke P. W. A Review on Fuel Ethanol Production From Lignocellulosic Biomass. Int. J. Green Energy 2015, 12, 949–960. 10.1080/15435075.2014.890104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kober P. A. Pervaporation, perstillation and percrystallization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1917, 39, 944–948. 10.1021/ja02250a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolto B.; Hoang M.; Xie Z. A review of membrane selection for the dehydration of aqueous ethanol by pervaporation. Chem. Eng. Process. 2011, 50, 227–235. 10.1016/j.cep.2011.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Wei W.; Jin W. Pervaporation Membranes for Biobutanol Production. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 546–560. 10.1021/sc400372d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neto J. M.; Pinho M. N. Mass transfer modelling for solvent dehydration by pervaporation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2000, 18, 151–161. 10.1016/s1383-5866(99)00061-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaban H. I. Pervaporation separation of water from organic mixtures. Sep. Purif. Technol. 1997, 11, 119–126. 10.1016/s1383-5866(97)00008-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anjali Devi D.; Smitha B.; Sridhar S.; Aminabhavi T. M. Pervaporation separation of isopropanol/water mixtures through crosslinked chitosan membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2005, 262, 91–99. 10.1016/j.memsci.2005.03.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. H.; Liu Q. L.; Zhu A. M.; Zhang Q. G. Dehydration of acetic acid by pervaporation using SPEK-C/PVA blend membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 320, 416–422. 10.1016/j.memsci.2008.04.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek G.; Turczyn R.; Gnus M.; Konieczny K. Pervaporative dehydration of ethanol/water mixture through hybrid alginate membranes with ferroferic oxide nanoparticles. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 193, 398–407. 10.1016/j.seppur.2017.09.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury S.; Ray S. K. Filled copolymer membranes for pervaporative dehydration of ethanol-water mixture. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 179, 335–348. 10.1016/j.seppur.2017.01.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenes M. L.; Liu L.; Feng X. Sericin/poly(vinyl alcohol) blend membranes for pervaporation separation of ethanol/water mixtures. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 295, 71–79. 10.1016/j.memsci.2007.02.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumarnaidu B.; Sairam M.; Raju K.; Aminabhavi T. M. Pervaporation separation of water plus isopropanol mixtures using novel nanocomposite membranes of poly(vinyl alcohol) and polyaniline. J. Membr. Sci. 2005, 260, 142–155. 10.1016/j.memsci.2005.03.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doguparthy S. Pervaporation of aqueous alcohol mixtures through a photopolymerised composite membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2001, 185, 201–205. 10.1016/s0376-7388(00)00654-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng P.-I.; Hong P.-D.; Lee K.-R.; Lai J.-Y.; Tsai Y.-L. High permselectivity of networked PVA/GA/CS-Ag+-membrane for dehydration of Isopropanol. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 564, 926–934. 10.1016/j.memsci.2018.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khoonsap S.; Supanchaiyamat N.; Hunt A. J.; Klinsrisuk S.; Amnuaypanich S. Improving water selectivity of poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) - Fumed silica (FS) nanocomposite membranes by grafting of poly (2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (PHEMA) on fumed silica particles. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 122, 373–383. 10.1016/j.ces.2014.09.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler S. Z.; Hollen S. M.; Cao L.; Cui Y.; Gupta J. A.; Gutiérrez H. R.; Heinz T. F.; Hong S. S.; Huang J.; Ismach A. F.; Johnston-Halperin E.; Kuno M.; Plashnitsa V. V.; Robinson R. D.; Ruoff R. S.; Salahuddin S.; Shan J.; Shi L.; Spencer M. G.; Terrones M.; Windl W.; Goldberger J. E. Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities in Two-Dimensional Materials Beyond Graphene. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 2898–2926. 10.1021/nn400280c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geim A. K.; Novoselov K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 183–191. 10.1038/nmat1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.; Murali S.; Cai W.; Li X.; Suk J. W.; Potts J. R.; Ruoff R. S. Graphene and Graphene Oxide: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 3906–3924. 10.1002/adma.201001068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Li M.; Zhou S.; Xue A.; Zhang Y.; Zhao Y.; Zhong J.; Zhang Q. Graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets embedded in poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposite membranes for ethanol dehydration via pervaporation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 188, 24–37. 10.1016/j.seppur.2017.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Li L.; Wei Y.; Xue J.; Chen H.; Ding L.; Caro J.; Wang H. Water Transport with Ultralow Friction through Partially Exfoliated g-C3N4 Nanosheet Membranes with Self-Supporting Spacers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 8974–8980. 10.1002/anie.201701288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasik A.; Lin Y. S. Organic solvent pervaporation properties of MOF-5 membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 121, 38–45. 10.1016/j.seppur.2013.04.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mak K. F.; Lee C.; Hone J.; Shan J.; Heinz T. F. Atomically Thin MoS2: A New Direct-Gap Semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 666. 10.1103/physrevlett.105.136805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G.; Li Y.; Geng Y.; Lu X.; Jia Z. Adjustable pervaporation performance of Zr-MOF/poly(vinyl alcohol) mixed matrix membranes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 94, 973–981. 10.1002/jctb.5846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Wang Y. Poly(vinylalcohol)/ZIF-8-NH2 Mixed Matrix Membranes for Ethanol Dehydration via Pervaporation. AIChE J. 2016, 62, 1728–1739. 10.1002/aic.15140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.; Lee J.; Lee G.; Lee J.; Song H.; Jho J. Y.; Lee H. H.; Kim Y. H. Synthesis of a Carbonaceous Two-Dimensional (2D) Material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 21308–21313. 10.1021/acsami.9b01808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Jin W.; Xu N. Two-Dimensional-Material Membranes: A New Family of High-Performance Separation Membranes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13384–13397. 10.1002/anie.201600438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang X.; Mai Y.; Wu D.; Zhang F.; Feng X. Two-Dimensional Soft Nanomaterials: A Fascinating World of Materials. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 403–427. 10.1002/adma.201401857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L.; Lin H. Engineering Sub-Nanometer Channels in Two-Dimensional Materials for Membrane Gas Separation. Membr 2018, 8, 100. 10.3390/membranes8040100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naguib M.; Kurtoglu M.; Presser V.; Lu J.; Niu J.; Heon M.; Hultman L.; Gogotsi Y.; Barsoum M. W. Two-Dimensional Nanocrystals Produced by Exfoliation of Ti3AlC2. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 4248–4253. 10.1002/adma.201102306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naguib M.; Halim J.; Lu J.; Cook K. M.; Hultman L.; Gogotsi Y.; Barsoum M. W. New Two-Dimensional Niobium and Vanadium Carbides as Promising Materials for Li-Ion Batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 15966–15969. 10.1021/ja405735d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghidiu M.; Lukatskaya M. R.; Zhao M.-Q.; Gogotsi Y.; Barsoum M. W. Conductive two-dimensional titanium carbide ’clay’ with high volumetric capacitance. Nat 2014, 516, 78–81. 10.1038/nature13970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L.; Wei Y.; Wang Y.; Chen H.; Caro J.; Wang H. A Two-Dimensional Lamellar Membrane: MXene Nanosheet Stacks. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1825–1829. 10.1002/anie.201609306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C. E.; Hatzell K. B.; Alhabeb M.; Ling Z.; Mahmoud K. A.; Gogotsi Y. Charge- and Size-Selective Ion Sieving Through Ti3C2Tx MXene Membranes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 4026–4031. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.; Sun Y.; Zhuang Y.; Jing W.; Ye H.; Cui Z. Assembly of 2D MXene nanosheets and TiO2 nanoparticles for fabricating mesoporous TiO2-MXene membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 564, 35–43. 10.1016/j.memsci.2018.03.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Shen J.; Liu Q.; Liu G.; Xiong J.; Yang J.; Jin W. Ultrathin two-dimensional MXene membrane for pervaporation desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 548, 548–558. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.11.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Ding L.; Lu Z.; Deng J.; Wei Y. Two-dimensional MXene membrane for ethanol dehydration. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 590, 117300. 10.1016/j.memsci.2019.117300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L.; Wei Y.; Li L.; Zhang T.; Wang H.; Xue J.; Ding L.-X.; Wang S.; Caro J.; Gogotsi Y. MXene molecular sieving membranes for highly efficient gas separation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 155–161. 10.1038/s41467-017-02529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Zhang T.; Duan Y.; Wei Y.; Dong C.; Ding L.; Qiao Z.; Wang H. Selective gas diffusion in two-dimensional MXene lamellar membranes: insights from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 11734–11742. 10.1039/c8ta03701a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.; Liu G.; Ye H.; Jin W.; Cui Z. Two-dimensional MXene incorporated chitosan mixed-matrix membranes for efficient solvent dehydration. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 563, 625–632. 10.1016/j.memsci.2018.05.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Zhu M.; Zhao Q.; An Q.; Qian J.; Lee K.; Lai J. The chemical crosslinking of polyelectrolyte complex colloidal particles and the pervaporation performance of their membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 385–386, 132–140. 10.1016/j.memsci.2011.09.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z.; Liu Q.; Wu C.; Wang H.; Wang H. Viscosity-driven in situ self-assembly strategy to fabricate cross-linked ZIF-90/PVA hybrid membranes for ethanol dehydration via pervaporation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 201, 256–267. 10.1016/j.seppur.2018.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z.; Wei Y.; Deng J.; Ding L.; Li Z.-K.; Wang H. Self-Crosslinked MXene (Ti3C2Tx) Membranes with Good Antiswelling Property for Monovalent Metal Ion Exclusion. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 10535–10544. 10.1021/acsnano.9b04612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X.; Cai W.; Chen X.; Shi Z.; Li J. Preparation of graphene oxide/poly(vinyl alcohol) composite membrane and pervaporation performance for ethanol dehydration. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 15457–15465. 10.1039/c9ra01379b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X.; Wang T.; Li Y.; Chen J.; Li J. Fabrication and characterization of micro-patterned PDMS composite membranes for enhanced ethanol recovery. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 563, 447–459. 10.1016/j.memsci.2018.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ong Y. K.; Shi G. M.; Le N. L.; Tang Y. P.; Zuo J.; Nunes S. P.; Chung T.-S. Recent membrane development for pervaporation processes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016, 57, 1–31. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2016.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narkkun T.; Jenwiriyakul W.; Amnuaypanich S. Dehydration performance of double-network poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposite membranes (PVAs-DN). J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 528, 284–295. 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.12.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Wang H.; Wu C.; Wei Z.; Wang H. In-situ generation of iron-dopamine nanoparticles with hybridization and cross-linking dual-functions in poly (vinyl alcohol) membranes for ethanol dehydration via pervaporation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 188, 282–292. 10.1016/j.seppur.2017.06.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suhas D. P.; Aminabhavi T. M.; Raghu A. V. Mixed Matrix Membranes of H-ZSM5-Loaded Poly(vinyl alcohol) Used in Pervaporation Dehydration of Alcohols: Influence of Silica/Alumina Ratio. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2014, 54, 1774–1782. 10.1002/pen.23717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penkova A. V.; Dmitrenko M. E.; Savon N. A.; Missyul A. B.; Mazur A. S.; Kuzminova A. I.; Zolotarev A. A.; Mikhailovskii V.; Lahderanta E.; Markelov D. A.; Semenov K. N.; Ermakov S. S. Novel mixed-matrix membranes based on polyvinyl alcohol modified by carboxyfullerene for pervaporation dehydration. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 204, 1–12. 10.1016/j.seppur.2018.04.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z.; Guan H.; Tan W.; Qiao X.; Kulprathipanja S. Pervaporation study of aqueous ethanol solution through zeolite-incorporated multilayer poly(vinyl alcohol) membranes: Effect of zeolites. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 276, 260–271. 10.1016/j.memsci.2005.09.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeom C. K.; Lee S. H.; Lee J. M. Pervaporative permeations of homologous series of alcohol aqueous mixtures through a hydrophilic membrane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 79, 703–713. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-C.; Fan S.-C.; Lee K.-R.; Li C.-L.; Huang S.-H.; Tsai H.-A.; Lai J.-Y. Polyamide/SDS-clay hybrid nanocomposite membrane application to water-ethanol mixture pervaporation separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2004, 239, 219–226. 10.1016/j.memsci.2004.03.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y.; Jiang Z.; Gao B.; Wang H.; Wang M.; He Z.; Cao X.; Pan F. Embedding hydrophobic MoS2 nanosheets within hydrophilic sodium alginate membrane for enhanced ethanol dehydration. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2018, 185, 231–242. 10.1016/j.ces.2018.03.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.-F.; Ho J.-C.; Andrew Lin K.-Y.; Tung K.-L.; Chung T.-W.; Lee C.-C. A drying-free and one-step process for the preparation of siloxane/CS mixed-matrix membranes with outstanding ethanol dehydration performances. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 221, 325–330. 10.1016/j.seppur.2019.03.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]