Abstract

The antiviral effects of chloroquine (CQ) on human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) infection of human fetal lung cell line, L132 are reported. CQ significantly decreased the viral replication at concentrations lower than in clinical usage. We demonstrated that CQ affects the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). Furthermore, p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB203580, inhibits CPE induced by HCoV-229E infection and viral replication. Our findings suggest that CQ affects the activation of MAPKs, involved in the replication of HCoV-229E.

Keywords: Coronavirus, 229E, Chloroquine, p38, MAPK, ERK

Chloroquine (CQ), a diprotic weak base that increases the pH of acidic vesicles, has been used for the treatment of malaria and inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis. CQ has antimicrobial effects even against viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and SARS-CoV (Sperber et al., 1993, Savarino et al., 2003, Vincent et al., 2005). However, the inhibitory effect on SARS-CoV is inactive in vivo (Barnard et al., 2006), and the detailed mechanisms underlying the antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects of CQ remain poorly understood.

Coronavirus, an enveloped virus, enters the cytoplasm by endocytosis and matures in the membrane transport system, such as the trans-Golgi network (TGN) (Nauwynck et al., 1999, Ng et al., 2003). ER stress caused by Japanese encephalitis virus infection induces the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and host cell apoptosis (Su et al., 2002). MAPKs including ERK, JNK and p38 are involved in cell death (Xia et al., 1995) play a crucial role in infection of coronaviruses, such as mouse hepatitis virus and SARS-CoV (Banerjee et al., 2002, Kopecky-Bromberg et al., 2006).

CQ inhibits the activation of p38 MAPK and cytokine production caused by CpG DNA (Yi and Krieg, 1998). ERK, another MAPK associated with cell proliferation (Xia et al., 1995), is also affected by virus infection and CQ (Pleschka et al., 2001, Weber et al., 2002). In this study, we examined the correlation between CQ and the activation of p38 MAPK and ERK in human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) infection, and demonstrated the involvement of p38 MAPK in the replication of HCoV-229E.

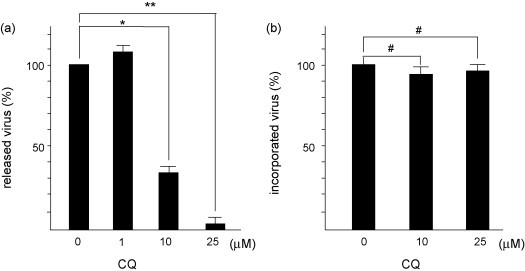

To examine the effect of CQ on the viral replication, virus in the supernatants was quantified by measuring the HCoV-229E RNA by reverse transcription (RT) real-time PCR. RNA from culture supernatants was extracted by using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to manufacturer's instructions and used for RT real-time PCR using specific primers for CoV229E N gene (forward: 5′-CAGTCAAATGGGCTGATGCA-3′, reverse: 5′-AAAGGGCTATAAAGAGAATAAGGTATTCT-3′) and a probe (5′-CCCTGACGACCACGTTGTGGTTCA-3′) (van Elden et al., 2004). CQ (10 and 25 μM) inhibited the release of HCoV-229E into supernatants significantly in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1a). Since CQ has both prophylactic and therapeutic antiviral effects for SARS-CoV (Vincent et al., 2005), its effect on the internalization of HCoV-229E into cells was evaluated. We quantified the HCoV-229E RNA incorporated into the cells at 3h post infection by real-time RT-PCR. The ratios of viral mRNA to 18s rRNA in the reactive units of quantitative real-time PCR were determined. The amount of viral RNA incorporated into the cells was not significantly influenced by CQ (Fig. 1b). These data demonstrate that CQ has no influence on the process prior to the internalization of HCoV-229E into L132 cells.

Fig. 1.

Inhibitory effects of CQ on virus replication and infectivity of HCoV-229E. (a) Effect of CQ on the released virus in supernatants. L132 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of CQ and adsorbed with HCoV-229E at an MOI of 3. RNA was extracted from culture supernatants and used for reverse transcriptional real-time PCR at 3 h post infection. The amount of viral RNA in CQ-untreated cells was calculated as 100%. (b) Effect of CQ on the cytoplasmic viral RNA. L132 cells were pretreated with indicated concentrations of CQ, and infected by HCoV-229E at an MOI of 3. At 3 h post infection, cellular RNA was extracted and used for reverse transcriptional real-time PCR. Data represent mean ± S.E. in triplicate.

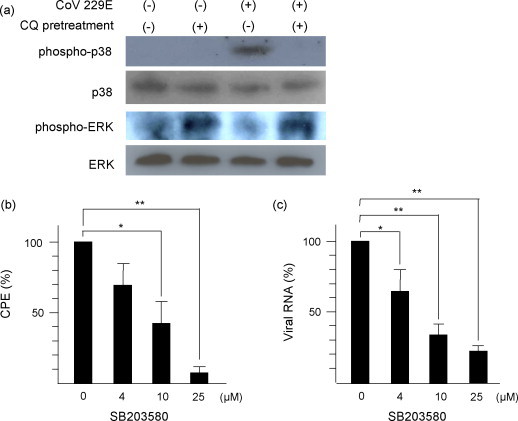

Since CQ was not involved in the process of internalization of HCoV-229E into the cells, we examined its effect on the activation of p38 MAPK and ERK, since they might be involved in the process after internalization. The activation of p38 MAPK and ERK at 90 min post infection (p.i.) was examined by immunoblotting. The HCoV-229E-infected cells were harvested at 90 min p.i. and the lysate protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Extracted protein (20 μg) was separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). The membranes were blocked with skim milk and incubated with primary antibodies to phosphorylated p38 MAPK, phosphorylated ERK, p38 MAPK (Cell Signaling Technology), and ERK (BD Biosciences Pharmingen) overnight at 4 °C. The membranes were washed and then incubated with 1:2000 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin for 1 h. Proteins were visualized with SuperSignal West Dura substrate reagent (Pierce) in the linear range on X-ray films.

HCoV-229E infection induced the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK which was inhibited by 25 μM CQ. Representative results are shown in Fig. 2a. However, the phosphorylation of ERK was enhanced 1.4- and 2.4-fold by CQ with mock and HCoV-229E infection, respectively, while the status of ERK was not significantly affected by HCoV-229E infection at 90 min p.i. These data demonstrate that CQ can neutralize the effect of HCoV-229E-infection on p38 MAPK.

Fig. 2.

Involvement of p38 and ERK in the infection of HCoV-229E. (a) Effect of CQ on the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and ERK. L132 cells were pretreated for 2 h with or without CQ and infected with HCoV-229E at an MOI of 3. Cytoplasmic proteins extracted at 90 min post infection were immunoblotted and reacted with specific antibodies against indicated MAPKs. (b) Effect of p38 inhibitor SB203580 on the CPE. L132 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of SB203580, a specific p38 MAPK inhibitor, subsequently adsorbed with HCoV-229E at an MOI of 3. At 72 h post infection, the cells were stained with crystal violet and cell viability was measured. The absorbance of CQ-untreated cells was calculated as 100%. (c) Effect of p38 inhibitor SB203580 on the viral RNA load in supernatant at 0, 4, 10, and 25 μM of p38 inhibitor. L132 cells were pretreated with indicated concentrations of SB203580 and adsorbed with HCoV-229E at an MOI of 3. RNA extracted from culture supernatants were used for reverse transcription real-time PCR at 72 h post infection. The amount of viral RNA load in CQ-untreated cells was calculated as 100%. Data represent mean ± S.E.M. of triplicates.

To confirm the role of p38 MAPK in the HCoV-229E viral replication, p38 MAPK activity was blocked with its inhibitor SB203580 (10 and 25 μM) which had no effect on cell viability (data not shown) but significantly mediated a dose-dependent inhibition of CPE (Fig. 2b). This indicates that p38 MAPK activation is required for CPE induced by HCoV-229E. To examine if p38 MAPK is involved in the viral replication of HCoV-229E, the effect of SB203580 on the HCoV-229E released in culture supernatants was tested. SB203580 significantly reduced viral titers in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2c), demonstrating the involvement of p38 MAPK in HCoV-229E viral replication.

We demonstrated that CQ inhibits HCoV-229E replication. Additionally, our results revealed that CQ inhibits the activation of p38 MAPK in HCoV-229E-infected cells and evokes the activation of ERK independently of infection. Our study demonstrated that CQ inhibits the activation of p38 and SB203580 (p38 inhibitor) suppresses viral replication. This suggests that CQ may inhibit the CoV replication by suppressing the p38 activation.

References

- Banerjee S. Murine coronavirus replication-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation promotes interleukin-6 production and virus replication in cultured cells. J. Virol. 2002;76:5937–5948. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.5937-5948.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard D.L. Evaluation of immunomodulators, interferons and known in vitro SARS-CoV inhibitors for inhibition of SARS-CoV replication in BALB/c mice. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2006;17:275–284. doi: 10.1177/095632020601700505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecky-Bromberg 7a Protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus inhibits cellular protein synthesis and activates p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J. Virol. 2006;80:785–793. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.785-793.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauwynck H.J. Entry of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus into porcine alveolar macrophages via receptor-mediated endocytosis. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80:297–305. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-2-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M.L. Proliferative growth of SARS coronavirus in Vero E6 cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2003;84:3291–3303. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19505-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleschka S. Influenza virus propagation is impaired by inhibition of the Raf/MEK/ERK signalling cascade. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:301–305. doi: 10.1038/35060098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarino A. Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today's diseases? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003;3:722–727. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00806-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber K. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication by hydroxychloroquine in T cells and monocytes. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrov. 1993;9:9–13. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H.-L. Japanese encephalitis virus infection initiates endoplasmic reticulum stress and an unfolded protein response. J. Virol. 2002;76:4162–4171. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4162-4171.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Elden L.J. Frequent detection of human coronaviruses in clinical specimens from patients with respiratory tract infection by use of a novel real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;189:652–657. doi: 10.1086/381207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent M.J. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol. J. 2005;2:69. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S.M. Inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling by chloroquine. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5303–5309. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;24:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi A.K., Krieg A.M. Rapid induction of mitogen-activated protein kinases by immune stimulatory CpG DNA. J. Immunol. 1998;161:4493–4497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]