Highlights

-

•

Over-expression of the miR-26 family strongly inhibited PRRSV replication in two PRRSV genotypes in a dose-dependent manner.

-

•

Luciferase reporter gene assay showed miR-26a does not target PRRSV genome.

-

•

Over-expression of miR-26a increases the expression of type I IFN and the IFN-stimulated genes MX1 and ISG15 during PRRSV infection.

Keywords: miR-26a, PRRSV, Type I interferon, Virus replication

Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) play important roles in viral infections, especially by modulating the expression of cellular factors essential to viral replication or the host innate immune response to infection. To identify host miRNAs important to controlling porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) infection, we screened 15 miRNAs that were previously implicated in innate immunity or antiviral functions. Over-expression of the miR-26 family strongly inhibited PRRSV replication in vitro, as shown by virus titer assays, Western blotting, and qRT-PCR assays. MiR-26a inhibited the replication of both type 1 and type 2 PRRSV strains. Mutating the seed region of miR-26 restored viral titers. Luciferase reporters showed that miR-26a does not target the PRRSV genome directly but instead affects the expression of type I interferon and the IFN-stimulated genes MX1 and ISG15 during PRRSV infection. These results demonstrate the important role of miR-26a in modulating PRRSV infection and also support the possibility of using host miR-26a to achieve RNAi-mediated antiviral therapeutic strategies.

1. Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small (∼22 nucleotides) non-coding RNAs that bind to complementary sequences in the untranslated regions of target mRNAs and contribute to gene regulation by reducing mRNA translation or destabilizing transcripts (Grassmann and Jeang, 2008, Skalsky and Cullen, 2010). The commonly accepted mechanism of miRNA regulation is that the seed region (2 ∼ 8 nucleotides at the 5′ end) of an miRNA is complementary to the 5′ or 3′ untranslated region (5′- or 3′-UTR) of an mRNA, leading to mRNA degradation or translational inhibition (Bartel, 2009, Gottwein and Cullen, 2008). Recent work has shown the importance of miRNAs in regulating host–pathogen interactions and innate immunity (Lodish et al., 2008, Scaria et al., 2007, tenOever, 2013).

Host miRNAs can affect viral replication by binding directly to viral RNA (Lecellier et al., 2005) or by indirectly modulating host factors to provide a less permissive environment for virus replication (Triboulet et al., 2007). As miRNAs are small molecules without antigenic properties, they are considered to have potential efficacy in antiviral therapeutic applications. For example, human miR-122 is an essential component of the biology of hepatitis C virus replication (Jopling, 2010, Jopling et al., 2005) and therapeutic blocking of miR-122 suppresses hepatitis C viremia in non-human primates (Lanford et al., 2010).

Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus (PRRSV), a member of the arterivirus family, is the causative agent of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome [PRRS; (Chand et al., 2012)]. Based on their genetic and antigenic differences, PRRSV strains are classified into two distinct genotypes, North American (type 2) and European (type 1), represented by the VR-2332 (Benfield et al., 1992) and Lelystad virus (LV) (Wensvoort et al., 1991), respectively. These two genotypes on two different continents share only approximately 60% nucleotide sequence identity (Forsberg, 2005, Hanada et al., 2005). Many strategies for controlling PRRSV transmission have been proposed but have generally shown little success, which has stimulated the search for new ways to control PRRSV transmission.

PRRSV can escape from innate immunity and cause persistent infections (Miller et al., 2004). In mammalian cells, viral infection is a potent trigger of the interferon (IFN) response (Sadler and Williams, 2008, Sen, 2001). Type I interferons can initiate the activation of JAK/STAT signaling to induce the expression of hundreds of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), which play an important role in antiviral activities (Albina et al., 1998, Katze et al., 2002, Overend et al., 2007). However, in contrast to porcine respiratory coronavirus, PRRSV is a poor IFN-inducer (Buddaert et al., 1998).

Many miRNAs regulate IFN production (Li et al., 2014, Pedersen et al., 2007), maintain mRNA stability (Li et al., 2012), and regulate signals downstream of IFN to modulate antiviral immunity (Wang et al., 2010, Yoshikawa et al., 2012). While most miRNAs characterized to date decrease the production of IFNs (Alam and O’Neill, 2011), a few miRNAs that upregulate type I IFNs have been reported. Recent research has revealed that miR-23 may play a positive modulatory role in IFN production during PRRSV infection (Zhang et al., 2014).

Given the breadth of miRNA-mediated regulation of mammalian immunity (Grassmann and Jeang, 2008), the role of host miRNAs in PRRSV infection is of significant interest. Here, we found that miR-26a is an anti-PRRSV host factor. Over-expression of miR-26a inhibited infection by both of the major PRRSV genotypes in a dose-dependent manner. We found that miR-26a does not target the PRRSV genome directly, but rather affects the expression of type I interferon and the IFN-stimulated genes MX1 and ISG15 during PRRSV infection. Our study reveals an example of a miRNA that affects viral propagation and highlights a host factor that may be important for future control measures against PRRS.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells and viruses

MARC-145 cells were grown in MEM (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and were maintained with 2% FBS at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere as described previously (Yuan and Wei, 2008). Baby hamster kidney (BHK-21, ATCC CCL10) cells were cultured in EMEM (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS. Porcine alveolar macrophages (PAMs) were harvested from the lungs of 6-week-old PRRSV-negative piglets as described previously (Wensvoort et al., 1991) and maintained at 37 °C in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

vAPRRS (GenBank accession No. GQ330474) (Yuan and Wei, 2008) and vSHE (GenBank accession No. GQ461593) (Tian et al., 2011) were rescued from pAPRRS and pSHE, respectively. vJX143 (at passage 3) was isolated from the serum of a dying piglet displaying the clinical sings of porcine high fever disease (PHFD) in 2006. vJXM100 (GenBank accession No. GQ475526) was obtained through 100 serial passages of the highly pathogenic PRRSV vJX143 strain (EU708726) in MARC-145 cells (Wang et al., 2013). The infectious cDNA clone pJX143 was derived from vJX143 (Lv et al., 2008). High-titer virus stocks were obtained by infecting MARC-145 cells at low multiplicities of infection (MOIs). Infected cell supernatants were harvested after an 80% cytopathic effect (CPE) appeared, then the viruses were stored at −80 °C as stocks for further use. Virus titer was determined by standard TCID50 assay using MARC-145 cells.

2.2. miRNA mimics

miRNA mimics (Table 1 ), which are double-stranded 2′-O-methyl-modified RNA oligonucleotides with sequence complementarity to mature miRNAs were synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The sense sequences of the miR-26 mimics were: miR-26a- 5′-uucaaguaauccaggauaggcu-3′; miR-26b- 5′-uucaaguaauucaggauaggu-3′; corresponding non-seed-mutated miR-26 mimics (26-1A, 26-9U, and 26-1A9U) or seed-mutated miR-26 mimics (26a-m, 26b-m, c-m) are listed in Table 1 (underlined letters are mutated bases). The negative-control (NC) mimic sequence was 5′-uucuccgaacgugucacgutt-3′.

Table 1.

Sequences of microRNA (miRNA) mimics and inhibitors used in this study.

| Name | Sequence (5′−3′) |

|---|---|

| miR-21 | UAGCUUAUCAGACUGAUGUUGA |

| let-7a | UGAGGUAGUAGGUUGUAUAGUU |

| let-7b | UGAGGUAGUAGGUUGUGUGGUU |

| miR-30a-5p | UGUAAACAUCCUCGACUGGAAGCU |

| miR-30a-3p | CUUUCAGUCGGAUGUUUGCAGC |

| miR-30e-3p | CUUUCAGUCGGAUGUUUACAGC |

| miR-181b | AACAUUCAUUGCUGUCGGUGGGUU |

| miR-107 | AGCAGCAUUGUACAGGGCUAUCA |

| miR-197 | UUCACCACCUUCUCCACCCAGC |

| miR-146a | UGAGAACUGAAUUCCAUGGGUU |

| miR-125a-3p | ACAGGUGAGGUUCUUGGGAGC |

| miR-185 | UGGAGAGAAAGGCAGUUCCUGA |

| miR-423-5p | UGAGGGGCAGAGAGCGAGACUUU |

| miR-371-5p | ACUCAAACUGUGGGGGCACU |

| miR-26a | UUCAAGUAAUCCAGGAUAGGCU |

| miR-26b | UUCAAGUAAUUCAGGAUAGGU |

| 26-1A | AUCAAGUAAUCCAGGAUAGGCU |

| 26-9U | UUCAAGUAUUCCAGGAUAGGCU |

| 26-1A9U | AUCAAGUAUUCCAGGAUAGGCU |

| 26a-m | UAGUUCUAAUCCAGGAUAGGCU |

| 26b-m | UAGUUCUAAUUCAGGAUAGGU |

| NC | UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT |

| NC inhibitor | CAGUACUUUUGUGUAGUACAA |

| miR-26a inhibitor | AGCCUAUCCUGGAUUACUUGAA |

| miR-26b inhibitor | ACCUAUCCUGAAUUACUUGAA |

2.3. Transfection of miRNA mimic and viral multi-step growth kinetics

miRNA or NC mimics were transfected into PAMs or MARC-145 cells at a concentration of 80 nM (except for dose-dependence experiments) using X-tremeGENE siRNA Transfection Reagent (Roche). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were infected with PRRSV. For analysis of PRRSV growth, supernatants (0.2 ml/well) from cell cultures were collected at different time points post-infection and frozen at −80 °C. For virus quantification at each time point, a viral titer was measured in MARC-145 cells by standard TCID50 assay using the method of Reed and Muench (Reed and Muench, 1938).

2.4. IFA

Indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFA) were performed as described previously (Tian et al., 2011) for the detection of nucleocapsid (N) protein in PRRSV vJX143 infected MARC-145 cells or PAMs pre-transfected with miR-26 family or mutant mimics. Cells were fixed with cold methanol followed by blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and then incubated for 2 h with a monoclonal antibody (SR30A, Rural Technologies) that specifically recognizes type 2 PRRSV N proteins. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the cells were incubated for 1 h with Alexa Fluor 568-labeled goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Cell nuclei were counterstained with 1 μg/ml of 4′, 6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min. After a final PBS wash step, cells were visually analyzed using an Olympus inverted fluorescence microscope.

2.5. SDS–PAGE and Western blotting

MARC-145 cells were transfected with miR-26a or NC mimics prior to PRRSV infection. Cells were washed twice with PBS at 48 h post-infection and lysed with lysis buffer in the presence of 1 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). After incubation for 10 min on ice, cell lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C and the supernatants were collected. Protein samples were prepared in reducing buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.02% [wt./vol.] bromophenol blue, 100 mM DTT). Samples then were heated at 95 °C for 5 min, resolved on 15% SDS polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to Hybond-Pmembranes (Amersham Biosciences). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 0.1% Tween 20) for 2 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody (1AG11) that specifically recognizes both type 2 and type 1 PRRSV N proteins (kindly provided by Ingenasa Co., Madrid, Spain). After washing with TBST, blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Santa Cruz) for 1 h at room temperature, washed again with TBST, and developed using SuperSignal West Pico or Femto chemiluminescent substrate according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.6. RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA and miRNA were extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. PrimeScript™ 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara) was used for reverse transcription. Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) analysis was performed using a Step-one Plus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and a SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara). For detection of endogenous miRNAs, a commercial miRcute miRNA First-Strand cDNA Synthesis was purchased from TIANGEN BIOTECH (Beijing, China) and used for polyadenylation and reverse transcription. A commercial miRcute miRNA qPCR detection kit was purchased from TIANGEN BIOTECH (Beijing, China) for measuring miRNA abundance. MARC-145 cells infected with PRRSV at a MOI of 0.01 were collected at the indicated time points and total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). One μg of this total RNA was then used for reverse transcription with an RT-primer. The abundance of the miRNA of interest in the resulting cDNA was determined by qPCR using a universal reverse primer and a miRNA-specific forward primer. The PCR procedure comprised pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, and 40 cycles of 94 °C for 20 s, 60 °C for 15 s. The ubiquitously expressed U6 small nuclear RNA (TIANGEN) was used for normalization purpose. All primers used for miRNA qPCR were included in the commercial kit. The levels of ORF7 RNA, IFN-α/β, MX1, ISG15 mRNA were quantified using a SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara). Relative expression levels were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method (Bookout et al., 2006), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA was used as an endogenous control. Universal type I interferon was purchased from PBL InterferonSource. All PCR experiments were performed in triplicate. Other primers are listed in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Sequence of oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

| Primer | Sequence (5′−3′) |

|---|---|

| PGL3-5UTR-F | GCTCTAGAATGACGTATAGGTGTTGGCTC |

| PGL3-5UTR-F | TACTGCAGGGTTAAAGGGGTGGAGAGACC |

| PGL3-nsp1-F | GCTCTAGAATGTCTGGGATACTTGATCGGT |

| PGL3-nsp1-R | CGCTGCAGGTACCACTTATGACTGCCAAAC |

| PGL3-nsp2-F | ATTCTAGAGGTGCCGGAAAGAGAGCAAGGA |

| PGL3-nsp2-R | AACTGCAGCCCTGAAGGCTTGGAAATTTGC |

| PGL3-nsp3-F | ACTCTAGAGGAGGCCCACACCTCATTGCTG |

| PGL3-nsp3-R | ATCTGCAGCTCAAGGAGGGACCCGAGCTGA |

| PGL3-nsp4-F | GCTCTAGAGGCGCTTTCAGAACTCAAAA |

| PGL3-nsp4-R | ACCTGCAGTTCCAGTTCGGGTTTGGCAGCA |

| PGL3-nsp5-F | GCTCTAGAGGAGGCCTTTCCACAGTTCAAC |

| PGL3-nsp5-R | TCCTGCAGCTCGGCAAAGTATCGCAAGAAG |

| PGL3-nsp6-F | GATCTAGAGGAAAGTTGAGGGAAGGGGTGT |

| PGL3-nsp6-R | TACTGCAGCTCATGACTCATCCCGCAGG |

| PGL3-nsp7-F | GCTCTAGATCGCTGACTGGTGCCCTCG |

| PGL3-nsp7-R | TCCTGCAGTCCCACTGAGCTCTTCTATT |

| PGL3-nsp8-F | GCTCTAGAGCCGCCAAGCTTTCCGTGGAGC |

| PGL3-nsp8-R | TCCTGCAGCAGTTTAAACACTGCTCCTTAG |

| PGL3-nsp9-F | GATCTAGAGCCTGACTAAGGAGCAGTGTTT |

| PGL3-nsp9-R | GCCTGCAGCTCATGATTGGACCTGAGTTTT |

| PGL3-nsp10-F | GCTCTAGAGGGAAGAAGTCCAGAATGTGCG |

| PGL3-nsp10-R | TCCTGCAGTTCCAGGTCTGCGCAAATAG |

| PGL3-nsp11-F | AATCTAGAGGTCGAGCTCCCCGCTCCCCAA |

| PGL3-nsp11-R | CGCTGCAGTTCAAGTTGAAAATAGGCCGTC |

| PGL3-nsp12-F | ACTCTAGAGGCCGCCATTTTACCTGGTATC |

| PGL3-nsp12-R | CGCTGCAGTCAATTCAGGCCTAAAGTTGGT |

| PGL3-ORF2-F | GCTCTAGAATGAAATGGGGTCTATGCAAAGC |

| PGL3-ORF2-R | CGCTGCAGTCACCATGAGTTCAAAAGAAAAG |

| PGL3-ORF3-F | GCTCTAGAATGGCTAATAGCTGTACATTCC |

| PGL3-ORF3-R | AACTGCAGCTATCGCCGTGCGGCACTGAGAA |

| PGL3-ORF4-F | GCTCTAGAATGGCTGCGCCCTTTCTTTT |

| PGL3-ORF4-R | GCCTGCAGACTTAAACATTCAAATTGCCAG |

| PGL3-ORF5-F | ACTCTAGAATGTTGGGGAAGTGCTTGACCG |

| PGL3-ORF5-R | AGCTGCAGCTAGAGACGACCCCATTGTTCC |

| PGL3-ORF6-F | ACTCTAGAATGGGGTCGTCTCTAGAC |

| PGL3-ORF6-R | GCCTGCAGTTATTTGGCATATTTAACAAGG |

| PGL3-ORF7-F | ACTCTAGAATGCCAAATAACAACGGCAAGC |

| PGL3-ORF7-R | AGCTGCAGTCATGCTGAGGGTGATGCTGTG |

| PGL3-3UTR-F | AATCTAGATGGGCTGGCATTCTTTGGCAC |

| PGL3-3UTR-R | GCCTGCAGTTAATTACGGCCGCATGGTTC |

| ORF7-F | CCCTAGTGAGCGGCAATTGT |

| ORF7-R | TCCAGCGCCCTGATTGAA |

| mBeta-actin-F | TCATCACCATTGGCAATGAG |

| mBeta-actin-R | AGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG |

| mIFN-α-F | GCAGCATCTGCAACATCTAC |

| mIFN-α-R | GGATCATCTCATGGAGGACAG |

| mISG15-F | CACCGTGTTCATGAATCTGC |

| mISG15-R | CTTTATTTCCGGCCCTTGAT |

| IFN-α-F | AGCACTGGCTGGAATGAAACCG |

| IFN-α-R | CTCCAGGTCATCCATCTGCCCA |

| IFN-β-F | CTGCTGCCTGGAATGAGAGCC |

| IFN-β-R | TGACACAGGCTTCCAGGTCCC |

| GAPDH-F | CCTTCCGTGTCCCTACTGCCAAC |

| GAPDH-R | GACGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTCT |

| MX1-F | CACAGAACTGCCAAGTCCAA |

| MX1-R | GCAGTACACGATCTGCTCCA |

| ISG15-F | GGTGCAAAGCTTCAGAGACC |

| ISG15-R | GTCAGCCAGACCTCATAGGC |

2.7. Construction of luciferase reporters and luciferase assays

The pGL3-Control luciferase reporter vector (Promega) was used as the cloning vector for luciferase assays to analyze potential miR-26a target regions in the PRRSV genome. Twenty cDNA fragments encompassing the PRRSV genome were amplified by PCR from PRRSV pJX143 and subcloned into the pGL3-Control vector downstream of the luciferase ORF. The primers used are listed in Table 2. All cDNA constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Plasmids and miRNA mimics were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer′s protocol. For luciferase reporter assays, subconfluent BHK-21 cells cultured in 12-well plates were co-transfected with 500 ng/well of the indicated reporter plasmid and 100 ng/well of pRL-CMV (as an internal control to normalize transfection efficiency, Promega) along with the indicated amount of miR-26a mimic. Cells were lysed 24 h later for determination of firefly luciferase activities using the Luciferase assay system (Promega). Data are presented as the relative luciferase activities in miR-26a mimic-transfected cells relative to NC mimic-transfected controls and are representative of three independent experiments.

3. Results

3.1. miR-26a is an anti-PRRSV miRNA

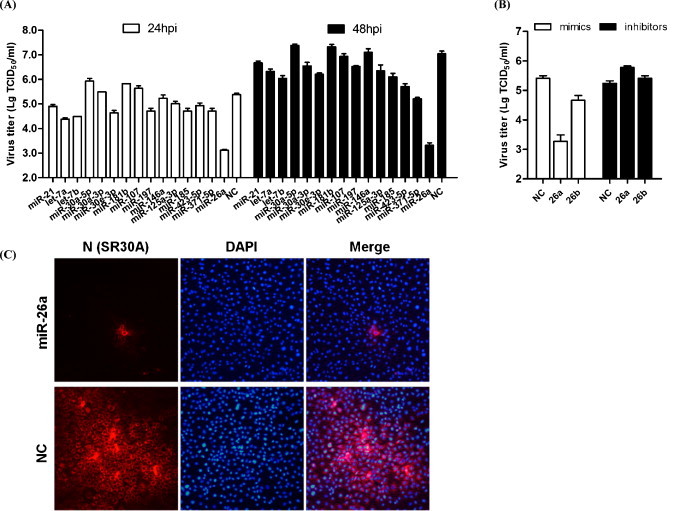

To screen potential miRNAs for their ability to inhibit PRRSV replication, mimics of 15 miRNAs that are well-conserved among different species and have been previously implicated in innate immunity and/or antiviral functions (Banerjee et al., 2013, Foley and O’Neill, 2012, Huang et al., 2014, Yoo and Liu, 2013, Pauley and Chan, 2008, Schulte et al., 2013, Selvamani et al., 2014) were synthesized (Table 1). MARC-145 cells were transfected with individual miRNA mimics (80 nM) and then infected with PRRSV (vAPRRS) at an MOI of 0.01. Supernatants from infected cells were collected at 24 and 48 h post-infection to determine viral titers. Among the miRNAs tested, over-expression of the miR-26a mimic strongly reduced PRRSV titers (Fig. 1A). Transfection of miR-26a/26b inhibitors demonstrated the opposite effects (Fig. 1B), indicating that miR-26 has antiviral activity against PRRSV replication and that miR-26a is a more efficient suppressor than miR-26b. All the other miRNA mimics tested had no demonstrable impact on PRRSV titers in MARC-145 cells (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, immunofluorescence assays using a FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibody against the PRRSV N protein were consistent with viral titer data (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

MicroRNA (miRNA) screening identifies miR-26a as an inhibitor of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) replication. A. Confluent MARC-145 cells were transfected with the indicated miRNAs mimics; NC = negative control mimic. After 24 h, cells were infected with PRRSV strain vAPRRS at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. The supernatants were collected at 24 and 48 h to determine viral titers. Virus titers were expressed as the log TCID50/ml. B. MARC-145 cells were transfected with miR-26a/26b mimics or inhibitors or negative control mimics (80 nM), followed by vAPRRS infection (MOI = 0.01). Supernatants were collected at 24 h for viral titer determination. C. Immunofluorescence staining against the PRRSV N protein after transfection and PRRSV vJX143 infection. MARC-145 cells were fixed at 36 h post-infection and immunostained with the mouse monoclonal SR30A antibody against the viral N protein and FITC-conjugated goat anti mouse IgG. Cellular nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1 mg/ml).

3.2. miR-26a inhibits multiple PRRSV strains in a dose-dependent manner

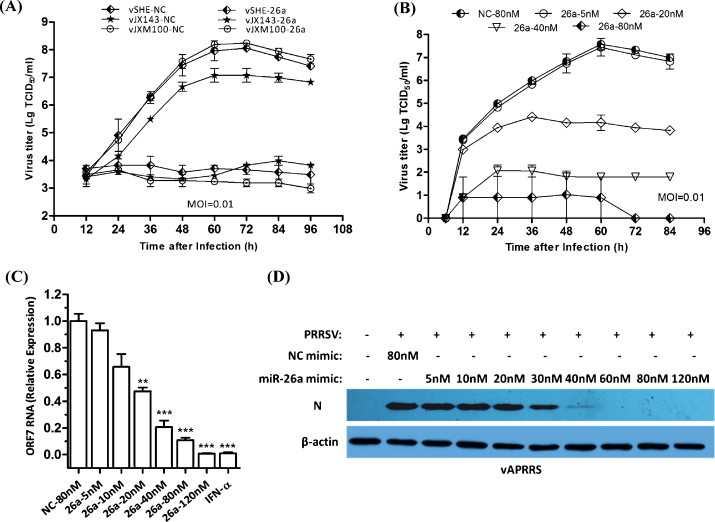

To rule out the possibility that this antiviral effect of miR-26a was specific to an individual PRRSV strain, we analyzed the viral growth curves of two type 2 PRRSV strains (vJX143, vJXM100) and a type 1 PRRSV strain (vSHE) in MARC-145 cells transfected with NC or miR-26a mimics. Over-expression of the miR-26a mimic, but not the NC mimic, reduced PRRSV replication in multiple PRRSV strains of differing genotypes (Fig. 2A). To corroborate our findings with miR-26a further, MARC-145 cells were transfected with increasing concentrations of miR-26a mimic (5, 20, 40, 80 nM) and then infected with vAPRRS. Both PRRSV growth and the amount of ORF7 mRNA level were inhibited as a function of the dose of miR-26a mimic (Fig. 2B and C). Consistent with this, transfecting the miR-26a mimic also reduced the accumulation of the PRRSV nucleocapsid (N) protein in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2D). To exclude the possibility that reduced PRRSV replication was due to potential toxicity of the miR-26a mimic, MARC-145 cells were transfected with the miR-26a mimic at different doses (40 nM, 80 nM, and 160 nM). No appreciable effect of the miR-26a mimic (at up to 160 nM) on cellular viability and morphology was observed (data not shown). Collectively, these data show that miR-26a reduces PRRSV replication in multiple PRRSV genotypes in a dose-dependent manner.

Fig. 2.

Overexpression of miR-26a mimics reduces replication of two PRRSV genotypes in a dose-dependent manner. A. Analysis PRRSV vSHE, vJX143 and vJXM100 growth in MARC-145 cells transfected with NC or miR-26a mimics (80 nM). Culture supernatants were collected at the indicated times and titrated. B. MARC-145 cells were transfected with miR-26a or NC mimics at the indicated doses (5–80 nM), followed by vAPRRS infection (MOI = 0.01). The supernatants were collected at the indicated times for viral titer determination. C. qRT-PCR analysis of ORF7 RNA levels in MARC-145 cells transfected with miR-26a or NC mimics at the indicated doses (5–120 nM) or stimulated with IFN-α (1000 U/ml), followed by vAPRRS infection (MOI = 0.01). The data were normalized to β-actin expression. D. The experiments were performed as described for panel C, except that the indicated doses (5–120 nM) were used. Cells were collected at 48 h post-infection for Western blot analysis of N protein expression. β-actin expression was analyzed as a loading control.

3.3. miR-26 family members had strong activity against PRRSV in PAMs

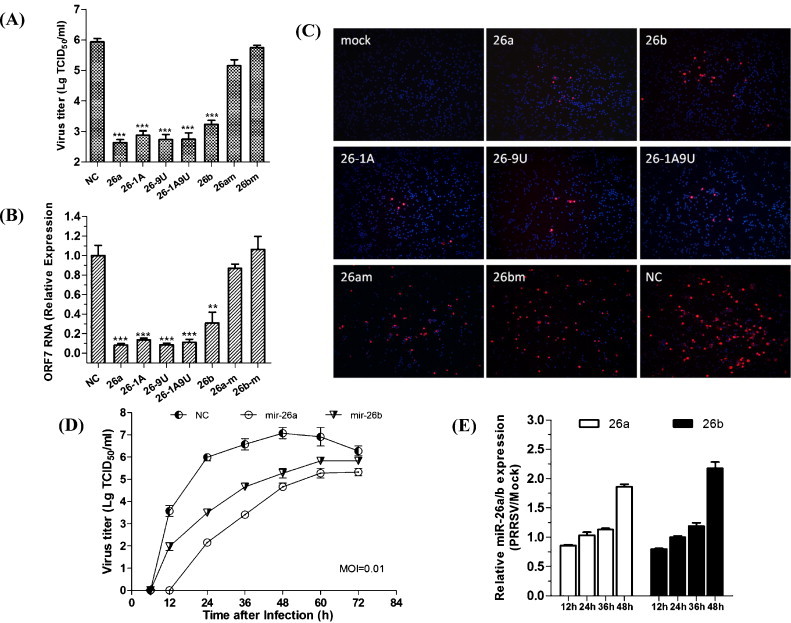

We next investigated the effect of other miR-26 miRNA and mutants on PRRSV replication. Because miR-26a is highly conserved between monkeys and pigs, we conducted the subsequent investigations in PAMs, which are the target cells of PRRSV infection in vivo. As previously reported, miRNA–mRNA interactions may require seed-matched sites at nucleotides 2–8 (Bartel, 2009). Thus, we mutated miR-26a mimic at non-seed nucleotides 1, 9, or 1 and 9 and miR-26 at seed nucleotides 2–6 (26a-m and 26b-m). Both miR-26a and miR-26b had anti-PRRSV activity in PAMs. PAMs transfected with miR-26a or miR-26b mimics yielded significantly lower PRRSV titers and ORF7 gene expression compared with cells transfected with the NC mimic (Fig. 3A and B). Three miR-26a mutants with non-seed mutations retained their ability to inhibit PRRSV progeny production and gene expression (Fig. 3A and B). By contrast, seed mutations at nts 2–6 abrogated the ability of miR-26 family members to repress PRRSV replication and gene expression (Fig. 3A and B), showing that the seed region was essential for inhibiting PRRSV replication.

Fig. 3.

PRRSV replication in PAMs transfected with miR-26 family mimics and mutated mimics. A. Viral titers and B. ORF7 mRNA expression in PAMs transfected with the indicated miR-26 mimics and mutated mimics for 24 h prior to PRRSV JX143 infection (MOI = 0.01). Data are the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was analyzed using t-tests; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. C. PAMs were transfected with the indicated miRNA mimics and then infected with PRRSV vJX143 (MOI = 0.01) for 24 h. Cells were fixed and immunostained with the mouse monoclonal SR30A antibody against the viral N protein and FITC-conjugated goat anti mouse IgG. Cellular nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1 mg/ml). D. PRRSV growth in PAMs transfected with miR-26 family mimics. PAMs were transfected with miR-26 family or NC mimics for 24 h and then infected with PRRSV vJX143 at an MOI of 0.01. Culture supernatants were collected at the indicated times and titrated. E. Time-course of miR-26a/26b expression after PRRSV infection. PAM cells infected with vJX143 at a MOI of 0.01 were collected at the indicated times and qRT-PCR analysis was performed to detect miR-26a/26b expression. Relative miR-26a/b expression refers to the change in miR-26a/b expression levels in PRRSV-infected PAMs relative to mock PAMs.

To investigate further inhibition effect of miR-26 family and mutants on PRRSV infection, we used an immunofluorescence assay to detect the PRRSV N protein in PAMs. N protein expression in PAMs was suppressed by both miR-26a and miR-26b (Fig. 3C, top) and by miR-26 non-seed mutants (Fig. 3C, middle), but was not affected by miR-26 seed mutants (Fig. 3C, bottom). We then analyzed the growth dynamics of HP-PRRSV isolate vJX143 in PAMs transfected with miR-26 family or NC mimics. Viral growth was suppressed about 1000-fold in PAMs transfected with miR-26a and about 100-fold in PAMs transfected with miR-26b at 24 h post-infection (Fig. 3D). Notably, miR-26a was more efficient suppressing viral growth than miR-26b. These results indicated that miR-26 family members, especially miR-26a, can inhibit vJX143 replication in PAMs. We then analyzed the kinetics of miR-26 expression in PRRSV infected PAM cells. The relative expression of miR-26 was upregulated as a function of PRRSV infection time (Fig. 3E).

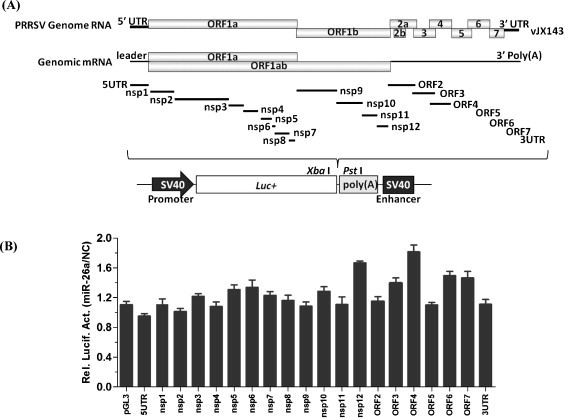

3.4. miR-26a does not directly target the PRRSV genome

Targeting a specific viral sequence represents an efficient strategy by which miRNAs can inhibit viral replication (Jopling, 2010, Lecellier et al., 2005). In recent studies, miR-181 and miR-23 were confirmed to reduce viral gene expression and viral growth due to direct targeting of PRRSV genomic RNA (Guo et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2014). We determined whether miR-26a specifically targets the PRRSV genome to exert its antiviral effect by constructing a range of firefly luciferase reporter pGL3-Control based plasmids, which contained the cDNA fragments representing the 5′ UTR, nsp1-nsp12, ORF2-ORF7, and the 3′ UTR of the PRRSV genome downstream of the firefly luciferase gene (Fig. 4A). If the PRRSV cDNA insert contains a miR-26a target sequence, luciferase reporter expression is expected to be subjected to miR-26a-regulation. MiR-26a or NC mimics were co-transfected with the individual reporter vectors into BHK-21 cells, along with an internal control vector pRL-CMV. Relative luciferase activities were quantified 24 h post-transfection. The relative luciferase activities for different vectors containing various PRRSV cDNA fragments were not significantly different between cells transfected with miR-26a mimic as compared with cells transfected with the NC mimic. Thus, miR-26a does not appear to target directly the PRRSV genome.

Fig. 4.

miR-26a does not directly target the PRRSV genome. A. Schematic representation of the PRRSV genome. Viral cDNA fragments used for constructing pGL3 target luciferase reporters are indicated. B. BHK-21 cells were co-transfected with 0.5 μg of the indicated luciferase reporters with miR-26a or NC mimics. At 24 h post-transfection, cells were lysed for luciferase assay. The relative luciferase activities (miR-26a/NC) refer to the fold change in luciferase activity in cells transfected with miR-26a mimics relative to cells transfected with NC mimics.

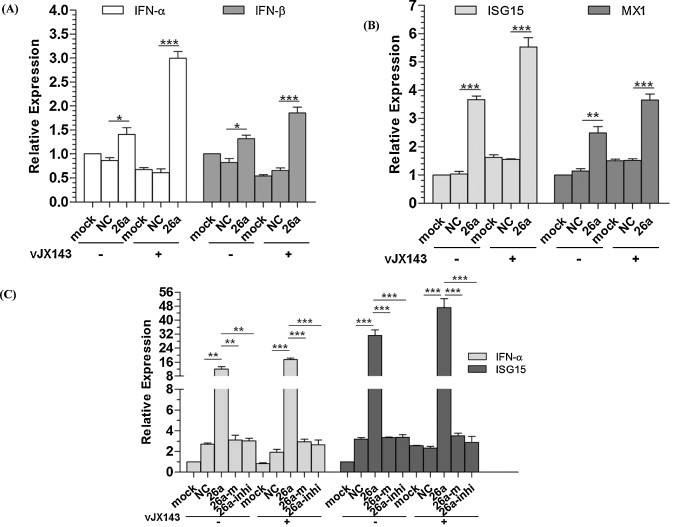

3.5. miR-26a increases the expression of type I IFN and the IFN-stimulated genes MX1 and ISG15 during PRRSV infection

We found that over-expression of miR-26a increased IFN-α/β expression during vJX143 infection (MOI = 0.01) at 36 h in PAMs as compared with over-expression of NC (Fig. 5A). The IFN-stimulated genes MX1 and ISG15 were also significantly upregulated (Fig. 5B). Transfecting the miR-26a mimic into PAMs in the absence of PRRSV infection also enhanced type I IFN expression (Fig. 5A and B). IFN-α and IFN-β were induced about 1.6-fold in un-infected PAMs, and about 4.9- and 2.8-fold in PRRSV infected PAMs, respectively. ISG15 and MX1 were increased about 3.5- and 2.2-fold in un-infected PAMs, and about 3.6- and 2.4-fold in PRRSV infected PAMs, respectively.

Fig. 5.

miR-26a increases type I IFN expression during PRRSV infection. qRT-PCR analysis of (A. type I IFN α/β and B. MX1/ISG15) expression in PAMs transfected with NC or miR-26a mimics or left untreated (mock) for 24 h, and then infected with vJX143 for 36 h at an MOI of 0.01, or left untreated. Data were normalized to GAPDH expression and are the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. C. qRT-PCR analysis of IFN-α and ISG15 expression in Marc-145 cells transfected with NC, miR-26a mimics or inhibitors, and then infected with vJX143 for 36 h at an MOI of 0.01. Data were normalized to β-actin expression. Statistical significance was analyzed using t-tests; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

In MARC-145 cells, over-expression of miR-26a up-regulated IFN-α and ISG15 more strongly (Fig. 5C). IFN-α and ISG15 were induced about 4.4- and 9.8-fold in un-infected MARC-145 cells, and about 9.1- and 20.4-fold in PRRSV infected MARC-145 cells, respectively. Transfection of miR-26a inhibitors did not increase the expression of IFN-α or ISG15 (Fig. 5C), confirming that the induction of the innate immune response is specifically mediated by miR-26a.

4. Discussion

There is a growing body of evidence that cellular miRNAs are important regulators of innate and adaptive immune responses and the intricate networks of host-pathogen interactions. Herein, we identified miR-26a as an inhibitor of PRRSV replication that does not directly target the PRRSV genome (Fig. 1, Fig. 4). Over-expressed miR-26a reduced PRRSV replication and viral gene expression (Fig. 2), in not only MARC-145 cells, but also in PAMs (Fig. 3), the main target cell for PRRSV replication in vivo, confirming the biological relevance of this finding. MiR-26a belongs to a broadly conserved miRNA family with perfectly identical sequences among vertebrates (Griffiths-Jones et al., 2006). Previous studies of miR-26a have shown that this miRNA is an important regulator of cell proliferation and differentiation that targets the SMAD1 transcription factor (Ezh2), a suppressor of skeletal muscle cell differentiation (Lu et al., 2011, Luzi et al., 2008, Sander et al., 2008, Zhang et al., 2011).

By infecting PAMs with PRRSV strain VR-2332, Liu et al. generated small RNA expression profiles at 12, 24 and 48 h post-infection to identify alterations in miRNA expression associated with PRRSV (Yoo and Liu, 2013). Overall, 40 cellular miRNAs were differentially expressed during at least one time point in PRRSV-infected PAMs. However, in this study, miR-26a was not mentioned (Yoo and Liu, 2013). Contrary to the previous study, we found that the expression of miR-26a was up-regulated about 2-fold at 48 h post-infection (Fig. 3E).

One mechanism by which host miRNAs regulate viral replication is the direct targeting of viral sequences (Jopling, 2010, Lecellier et al., 2005). However, PRRSV is a fast-evolving RNA virus (Prieto et al., 2009) and the relatively high mutation rate may limit the application of this kind of RNAi-mediated antiviral therapeutic. Cellular miRNAs can also indirectly modulate cellular pathways that perturb the viral life cycle. In particular, the activation or enhancement of innate antiviral immune pathways has been suggested to be responsible for the antiviral effect of certain miRNAs (Lecellier et al., 2005, Pedersen et al., 2007).

In the current study, the reduction of PRRSV replication by miR-26a did not appear to involve direct targeting of the PRRSV genomic RNA (Fig. 4). Moreover, this reduction occurred in both type 1 and type 2 PRRSV strains (Fig. 2A) although these two genotypes share only approximately 60% nucleotide sequence identity. These data led us to hypothesize that miR-26a might act on a cellular factor to reduce PRRSV replication.

The results presented here support a link between PRRSV replication and the altered expression of miR-26a in targeting host innate immune responses (Fig. 5). Type I interferons (IFNs) are potent antiviral cytokines whose expression is triggered through recognition of viral components by pattern recognition receptors via a cascade of signaling molecules (Sun et al., 2012). PAMs are the main target cells for PRRSV infection, and many gene expression studies have explored the immune response of PAMs to PRRSV. Such studies have shown that the expression levels of MX1, USP, IFN-β, IL-10, and TNF-α are affected by PRRSV infection (Albina et al., 1998, Luo et al., 2008, Van Reeth et al., 1999). Overall, these analyses suggest that PRRSV subverts host defenses by inhibiting the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Van Reeth et al., 1999) and stimulating weak production of IFN-α (Sun et al., 2012).

Our results showed that over-expression of miR-26a was capable of inducing expression of IFN-α/β and the IFN-stimulated genes ISG15 and MX1, which might result in activation of the IFN response and further lead to the inhibition of virus infection. The restoration of innate immune responses to produce type I IFNs in PAMs seems to be miRNA specific, because another miRNA (miR-181b) had no such effect (data not shown). Thus, it is possible that miR-26a-induced type I IFN expression can overcome PRRSV interference, contributing to viral clearance. This mechanism provides a higher genetic barrier to the emergence of viral escape mutants, so the identification and characterization of miR-26a as an inhibitor of PRRSV replication may open new ways to control future PRRS outbreaks, for which effective control measures remain scant.

Our results showed that miR-26a also can mediate the activation of IFNs in the absence of PRRSV infection (Fig. 5). The possible causes may relate to recent studies about a new function of miRNAs, which is independent of their conventional role in post-transcriptional gene regulation (Chen et al., 2013, Fabbri et al., 2012, Lehmann et al., 2012). MiR-21, miR-29a, and let-7b have dual functions; on one hand, they bind to Argonaute proteins and guide the silencing of target genes, and on the other hand, they act independently of Argonaute proteins by interacting directly with TLRs. Although there is no current evidence, miR-26a may also serve as ligands for TLRs and activate IFNs. Future studies will be necessary to unravel the diverse functions of miR-26a.

Overall, we demonstrated that over-expression of miR-26a inhibits PRRSV replication. Although clearly defining the target and physiological role of miR-26a remains an unfinished task, our study provided evidence that over-expression of miR-26a enhances IFN-α/β expression during PRRSV infection, suggesting that miR-26a could be used as a potential target for antiviral development.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the grants from the National Basic Research Program (973 Plan) (no. 2014CB542700), the National Natural Science foundation of China (no. 31100121, no. 31302098, no. 31300140), and the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (no. 11JC1415200).

References

- Alam M.M., O’Neill L.A. MicroRNAs and the resolution phase of inflammation in macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41(9):2482–2485. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albina E., Piriou L., Hutet E., Cariolet R., L’Hospitalier R. Immune responses in pigs infected with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1998;61(1):49–66. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(97)00134-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Cui H., Xie N., Tan Z., Yang S., Icyuz M., Thannickal V.J., Abraham E., Liu G. miR-125a-5p regulates differential activation of macrophages and inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288(49):35428–35436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.426866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136(2):215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfield D.A., Nelson E., Collins J.E., Harris L., Goyal S.M., Robison D., Christianson W.T., Morrison R.B., Gorcyca D., Chladek D. Characterization of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome (SIRS) virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332) J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1992;4(2):127–133. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookout A.L., Cummins C.L., Mangelsdorf D.J., Pesola J.M., Kramer M.F. High-throughput real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2006;73:15.8.1–15.8.28. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1508s73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddaert W., Van Reeth K., Pensaert M. In vivo and in vitro interferon (IFN) studies with the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998;440:461–467. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5331-1_59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand R.J., Trible B.R., Rowland R.R. Pathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2(3):256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liang H., Zhang J., Zen K., Zhang C.Y. microRNAs are ligands of Toll-like receptors. RNA. 2013;19(6):737–739. doi: 10.1261/rna.036319.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri M., Paone A., Calore F., Galli R., Gaudio E., Santhanam R., Lovat F., Fadda P., Mao C., Nuovo G.J., Zanesi N., Crawford M., Ozer G.H., Wernicke D., Alder H., Caligiuri M.A., Nana-Sinkam P., Perrotti D., Croce C.M. MicroRNAs bind to Toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic inflammatory response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109(31):E2110–E2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209414109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley N.H., O’Neill L.A. miR-107: a toll-like receptor-regulated miRNA dysregulated in obesity and type II diabetes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012;92(3):521–527. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0312160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg R. Divergence time of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus subtypes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22(11):2131–2134. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwein E., Cullen B.R. Viral and cellular microRNAs as determinants of viral pathogenesis and immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3(6):375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassmann R., Jeang K.T. The roles of microRNAs in mammalian virus infection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1779(11):706–711. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S., Grocock R.J., van Dongen S., Bateman A., Enright A.J. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D140–D144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X.K., Zhang Q., Gao L., Li N., Chen X.X., Feng W.H. Increasing expression of microRNA 181 inhibits porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication and has implications for controlling virus infection. J. Virol. 2013;87(2):1159–1171. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02386-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada K., Suzuki Y., Nakane T., Hirose O., Gojobori T. The origin and evolution of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22(4):1024–1031. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Ma G., Fu L., Jia H., Zhu M., Li X., Zhao S. Pseudorabies viral replication is inhibited by a novel target of miR-21. Virology. 2014;456–457:319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling C.L. Targeting microRNA-122 to treat Hepatitis C virus infection. Viruses. 2010;2(7):1382–1393. doi: 10.3390/v2071382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling C.L., Yi M., Lancaster A.M., Lemon S.M., Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific MicroRNA. Science. 2005;309(5740):1577–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1113329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katze M.G., He Y., Gale M., Jr. Viruses and interferon: a fight for supremacy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2(9):675–687. doi: 10.1038/nri888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanford R.E., Hildebrandt-Eriksen E.S., Petri A., Persson R., Lindow M., Munk M.E., Kauppinen S., Orum H. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2010;327(5962):198–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1178178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecellier C.H., Dunoyer P., Arar K., Lehmann-Che J., Eyquem S., Himber C., Saib A., Voinnet O. A cellular microRNA mediates antiviral defense in human cells. Science. 2005;308(5721):557–560. doi: 10.1126/science.1108784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann S.M., Kruger C., Park B., Derkow K., Rosenberger K., Baumgart J., Trimbuch T., Eom G., Hinz M., Kaul D., Habbel P., Kalin R., Franzoni E., Rybak A., Nguyen D., Veh R., Ninnemann O., Peters O., Nitsch R., Heppner F.L., Golenbock D., Schott E., Ploegh H.L., Wulczyn F.G., Lehnardt S. An unconventional role for miRNA: let-7 activates Toll-like receptor 7 and causes neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15(6):827–835. doi: 10.1038/nn.3113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Duan X., Li Y., Liu B., McGilvray I., Chen L. MicroRNA-130a inhibits HCV replication by restoring the innate immune response. J. Viral Hepat. 2014;21(2):121–128. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Fan X., He X., Sun H., Zou Z., Yuan H., Xu H., Wang C., Shi X. MicroRNA-466l inhibits antiviral innate immune response by targeting interferon-alpha. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2012;9(6):497–502. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodish H.F., Zhou B., Liu G., Chen C.Z. Micromanagement of the immune system by microRNAs. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8(2):120–130. doi: 10.1038/nri2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., He M.L., Wang L., Chen Y., Liu X., Dong Q., Chen Y.C., Peng Y., Yao K.T., Kung H.F., Li X.P. MiR-26a inhibits cell growth and tumorigenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma through repression of EZH2. Cancer Res. 2011;71(1):225–233. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R., Xiao S., Jiang Y., Jin H., Wang D., Liu M., Chen H., Fang L. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) suppresses interferon-beta production by interfering with the RIG-I signaling pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2008;45(10):2839–2846. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzi E., Marini F., Sala S.C., Tognarini I., Galli G., Brandi M.L. Osteogenic differentiation of human adipose tissue-derived stem cells is modulated by the miR-26a targeting of the SMAD1 transcription factor. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2008;23(2):287–295. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J., Zhang J., Sun Z., Liu W., Yuan S. An infectious cDNA clone of a highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus variant associated with porcine high fever syndrome. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89(Pt 9):2075–2079. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/001529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L.C., Laegreid W.W., Bono J.L., Chitko-McKown C.G., Fox J.M. Interferon type I response in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus-infected MARC-145 cells. Arch. Virol. 2004;149(12):2453–2463. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0377-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overend C., Mitchell R., He D., Rompato G., Grubman M.J., Garmendia A.E. Recombinant swine beta interferon protects swine alveolar macrophages and MARC-145 cells from infection with Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2007;88(Pt 3):925–931. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauley K.M., Chan E.K. MicroRNAs and their emerging roles in immunology. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1143:226–239. doi: 10.1196/annals.1443.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen I.M., Cheng G., Wieland S., Volinia S., Croce C.M., Chisari F.V., David M. Interferon modulation of cellular microRNAs as an antiviral mechanism. Nature. 2007;449(7164):919–922. doi: 10.1038/nature06205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto C., Vazquez A., Nunez J.I., Alvarez E., Simarro I., Castro J.M. Influence of time on the genetic heterogeneity of Spanish porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates. Vet. J. 2009;180(3):363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed L.J., Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hygiene. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Sadler A.J., Williams B.R. Interferon-inducible antiviral effectors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8(7):559–568. doi: 10.1038/nri2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander S., Bullinger L., Klapproth K., Fiedler K., Kestler H.A., Barth T.F., Moller P., Stilgenbauer S., Pollack J.R., Wirth T. MYC stimulates EZH2 expression by repression of its negative regulator miR-26a. Blood. 2008;112(10):4202–4212. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaria V., Hariharan M., Pillai B., Maiti S., Brahmachari S.K. Host-virus genome interactions: macro roles for microRNAs. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9(12):2784–2794. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte L.N., Westermann A.J., Vogel J. Differential activation and functional specialization of miR-146 and miR-155 in innate immune sensing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(1):542–553. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvamani S.P., Mishra R., Singh S.K. Chikungunya virus exploits miR-146a to regulate NF-kappaB pathway in human synovial fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e103624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen G.C. Viruses and interferons. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001;55:255–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalsky R.L., Cullen B.R. Viruses, microRNAs, and host interactions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;64:123–141. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Han M., Kim C., Calvert J.G., Yoo D. Interplay between interferon-mediated innate immunity and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Viruses. 2012;4(4):424–446. doi: 10.3390/v4040424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- tenOever B.R. RNA viruses and the host microRNA machinery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;11(3):169–180. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian D., Zheng H., Zhang R., Zhuang J., Yuan S. Chimeric porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses reveal full function of genotype 1 envelope proteins in the backbone of genotype 2. Virology. 2011;412(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triboulet R., Mari B., Lin Y.L., Chable-Bessia C., Bennasser Y., Lebrigand K., Cardinaud B., Maurin T., Barbry P., Baillat V., Reynes J., Corbeau P., Jeang K.T., Benkirane M. Suppression of microRNA-silencing pathway by HIV-1 during virus replication. Science. 2007;315(5818):1579–1582. doi: 10.1126/science.1136319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Reeth K., Labarque G., Nauwynck H., Pensaert M. Differential production of proinflammatory cytokines in the pig lung during different respiratory virus infections: correlations with pathogenicity. Res. Vet. Sci. 1999;67(1):47–52. doi: 10.1053/rvsc.1998.0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Hou J., Lin L., Wang C., Liu X., Li D., Ma F., Wang Z., Cao X. Inducible microRNA-155 feedback promotes type I IFN signaling in antiviral innate immunity by targeting suppressor of cytokine signaling 1. J. Immunol. 2010;185(10):6226–6233. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Sun L., Li Y., Lin T., Gao F., Yao H., He K., Tong G., Wei Z., Yuan S. Development of a differentiable virus via a spontaneous deletion in the nsp2 region associated with cell adaptation of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res. 2013;171(1):150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensvoort G., Terpstra C., Pol J.M., ter Laak E.A., Bloemraad M., de Kluyver E.P., Kragten C., van Buiten L., den Besten A., Wagenaar F. Mystery swine disease in The Netherlands: the isolation of Lelystad virus. Vet. Q. 1991;13(3):121–130. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1991.9694296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J.A.H., Liu D.H.C. Characterization of the microRNAome in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infected macrophages. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e82054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa T., Takata A., Otsuka M., Kishikawa T., Kojima K., Yoshida H., Koike K. Silencing of microRNA-122 enhances interferon-alpha signaling in the liver through regulating SOCS3 promoter methylation. Sci. Rep. 2012;2:637. doi: 10.1038/srep00637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Wei Z. Construction of infectious cDNA clones of PRRSV: separation of coding regions for nonstructural and structural proteins. Sci. China C Life Sci. 2008;51(3):271–279. doi: 10.1007/s11427-008-0023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Liu X.X., He J.R., Zhou C.X., Guo M., He M., Li M.F., Chen G.Q., Zhao Q. Pathologically decreased miR-26a antagonizes apoptosis and facilitates carcinogenesis by targeting MTDH and EZH2 in breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(1):2–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Guo X.K., Gao L., Huang C., Li N., Jia X., Liu W., Feng W.H. MicroRNA-23 inhibits PRRSV replication by directly targeting PRRSV RNA and possibly by upregulating type I interferons. Virology. 2014;450–451:182–195. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]