Highlights

-

•

GRFT binds to the enveloped (E) and premature (prM) JEV glycoproteins.

-

•

Binding of GRFT to the JEV, competitively inhibited by mannose.

-

•

Pretreatment of GRFT with mannose, abolished its anti-JEV activity

Keywords: Griffithsin, Japanese encephalitis virus, Glycosylated proteins, Inhibition

Abstract

Griffithsin (GRFT) is a broad-spectrum antiviral protein against several glycosylated viruses. In our previous publication, we have shown that GRFT exerted antiviral activity against Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) infection. Herein, we further elucidated the mechanism by which GRFT inhibits JEV infection in BHK-21 cells. In vitro experiments using Pull-down assay and Co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP) assay showed that GRFT binds to the JEV glycosylated viral proteins, specifically the enveloped (E) and premature (prM) glycoproteins. The binding of GRFT to the JEV was competitively inhibited by increasing concentrations of mannose; in turns abolished anti-JEV activity of GRFT. We suggested that, the binding of GRFT to the glycosylated viral proteins may contribute to its anti-JEV activity. Collectively, our data indicated a possible mechanism by which GRFT exerted its anti-JEV activity. This observation suggests GRFT's potentials in the development of therapeutics against JEV or other flavivirus infection.

1. Introduction

Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) is a mosquito-borne virus belonging to the genus of Flavivirus. JEV infection ranks as a leading cause of high morbidity and mortality rate in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific region (Chung et al., 2007). The JEV genome contains structural and non-structural (NS) genes (Sumiyoshi et al., 1987a, Sumiyoshi et al., 1987b). There are three structural genes; capsid protein (C) and involved in capsid formation, pre-membrane (prM) and Envelope (E). The E protein (53–55 KDa) contains two potential glycosylation sites (Dutta et al., 2010) responsible for the virus attachment, fusion, penetration, cell tropism, virulence and attenuation (Lindenbach et al., 2007) while prM contains only one glycosylation site and is important for the virus release and pathogenesis (Kim et al., 2008). There are seven NS genes: NS1, NS2a, NS2b, NS3, NS4a, NS4b, NS5 and these are involved in the virus replication.

Griffithsin (GRFT) isolated from red alga Griffithsia sp is a plant-derived antiviral protein which exerts antiviral activity against several enveloped viruses, including severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) (O’Keefe et al., 2010a), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 (O’Keefe et al., 2009a) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Meuleman et al., 2011). It was found that, the purified GRFT exhibited antiviral activity comparable to the native one (Mori et al., 2005, O’Keefe et al., 2009b). GRFT has a high affinity to interact with the viral glycosylated proteins and prevent its entry into cells, and this was attributed to its dimeric structure that demonstrates six binding sites (Ziolkowska et al., 2006). In related studies, GRFT was found to bind the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV, gp120 of HIV-1 and E1 and E2 glycoproteins of HCV (O’Keefe et al., 2009a, O’Keefe et al., 2010a, Meuleman et al., 2011). In our previous study (Ishag et al., 2013), we have shown that, the GRFT could inhibit JEV infection. However, there is a critical gap in understanding of how GRFT functions effectively to inhibit JEV infection. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to further detail whether GRFT could also bind to the glycosylated JEV protein (E and prM) to inhibit its infection in BHK-21 cells. We found that, GRFT binds to the JEV glycosylated viral proteins, specifically E and prM. We also observed that, the incubation of GRFT with mannose before interacting with the virus, was competitively inhibited binding of GRFT to the virus, which blocks the anti-JEV effect of GRFT. We suggested that, the binding of GRFT to the glycosylated virus proteins, may contribute to its anti-JEV activity. In summary, our data suggested the mechanism and potential of GRFT in the development of therapeutics against JEV infection.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cells, virus and reagents

Baby hamster kidney (BHK)-21 cells were cultured at 37 °C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and antibiotics of penicillin (100 μg/ml) and streptomycin (100 U/ml). Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) strain SA14-14-2 (GenBank: JN604986) was propagated and titrated by plaque forming assay in BHK-21 cells and the virus titer was expressed as plaque forming unit/ml (pfu/ml). Mannose was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Anti-MYC and anti-His monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Abmart Company (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Recombinant GRFT protein

We previously de novo synthesized the GRFT DNA and cloned into pCold-1 to yield pCold-1-GRFT (Ishag et al., 2013). This construct was used to express and purify GRFT protein from E.coli expression system as we described before (Ishag et al., 2013). The purified GRFT protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Coomassie Blue Staining) and Western blot analysis using anti-His monoclonal antibody (Ishag et al., 2013).

2.3. Constructs of pCDNA3.1 vector

The MYC-tagged E and prM were PCR amplified from the viral genomic cDNA using EX Taq polymerase (TaKaRa) and were cloned into pcDNA3.І (+) vector (Invitrogen) at BamHI and XbaI sites or BamHI and XhoI sites to generate pcDNA3-E-MYCand pcDNA3-M-MYC respectively. HA-tagged GRFT was also PCR amplified and ligated into pcDNA3.1 (+) vector at KpnI and XbaI sites to generate pcDNA3-G-HA. The forward and reverse primers along with their sequences were used to amplify these fragments, are listed in Table 1 .

Table 1.

List of primers used to amplify E, prM (MYC-tag) and GRFT (HA-tag).

| Gene | Enzyme | Oligonucleotides Sequence (5′–3′) | Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| E | BamH1 | F: GCTGACGGATCCGCCACCATGTTTAATTGTCTGGGAATGG | 1550 bp |

| Xba1 | R: GTCGAGTCTAGATTACAGGTCTTCTTCAGAAATCAACTTCTGTTCAGCATGCACATTGG | ||

| prM | BamH1 | F: CGTATGGATCCGCCACCATGAAGTTGTCGAATTTC | 600 bp |

| XhoI | R:CCACTACTCGAGTTACAGGTCTTCTTCAGAGATCAGTTTCTGTTCACTGTAAGCCGGAGC | ||

| GRFT | Kpn1 | F:CAGTGTGGTACCGCCACCATGTCTCTTACTCACAGG | 380 bp |

| Xba1 | R:CTCCTATCTAGATTAAGCGTAATCTGGAACATCGTATGGGTAGTACTGCTCGTAGTA |

Note: Kozak sequences were in bold and introduced in forward primers. MYC-tag sequence was underlined and introduced in reverse primers of E and prM, while underlined HA-tag sequence was introduced in the reverse primer of GRFT. F = forward primer, R = reverse primer.

2.4. GRFT interacts specifically with E and prM, analyzed by Pull-down assay

The specific interaction of GRFT with E and prM was evaluated. BHK-21 cells (1 × 104 cells/well) were co-transfected (efficiency of over 70%) with 4 μg of plasmids (pcDNA3-E-MYC or pcDNA3-M-MYC using 10 μl of Polyethylenimine (PEI) (25 kDa; Sigma–Aldrich) for 24 h. The empty pcDNA3.1 vector was used as a control. The interaction of GRFT with E and prM, was then analyzed by Pull-down assay as previously indicated with minor modification (Ishag et al., 2013). Briefly, His-GRFT (5 μg) was preincubated with 50 μl of immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) beads (Novagen) in 0.5 ml binding buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 0.5% nonidet p-40 (NP-40) for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed five times by centrifugation at 2000 g for 2 min in 0.5 ml of washing buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 0.1% NP-40] to remove unbound GRFT. The resultant was incubated with lysate of cells transfected with E and prM plasmids separately for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads washed five times with washing buffer as described above to remove unbound E and prM proteins. The beads were boiled in 1 × SDS buffer (20 μl) and analyzed by Western blot using anti-MYC monoclonal antibody to detect the presence of E and prM proteins.

2.5. GRFT interacts specifically with E and prM, analyzed by Co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP) assay

BHK-21 cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3-E-MYC and pcDNA3-G-HA plasmids or pcDNA3-M-MYC and pcDNA3-G-HA plasmids as indicated above. The interaction of GRFT with E and prM, was then analyzed by CO-IP assay as previously demonstrated with minor modifications (Ishag et al., 2013, Li et al., 2014). Briefly, the lysate of cells transfected with mentioned plasmids, were incubated with 50 μl Protein G-Sepharose beads coupled with anti-HA (Dingguo, China) for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed five times with 0.5 ml of Co-IP buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 1% Triton X-100) by centrifugation at 2000 g for 2 min. The beads resuspended in 1 × SDS buffer (20 μl), boiled and the presences of E and prM proteins were then detected by Western blot using with anti-MYC monoclonal antibody. The expression of E and prM proteins in BHK-21 cells were first confirmed with anti-MYC while expression of GRFT protein was confirmed with anti-HA monoclonal antibody.

2.6. Competitive inhibition of GRFT binding activity by Mannose and its effect on the viral infectivity

To further evaluate the ability of GRFT to bind to JEV glycosylated proteins, we performed competitive assay using mannose. Herein, we preincubated mannose (5–100 μg/ml) was with 5 μg His-GRFT (mannose + His-GRFT) or mannose (100 μg/ml) with PBS as a control (mannose + PBS) for 30 min on a rocker and then added to 50 μl IMAC beads (mannose + His-GRFT + IMAC or mannose + PBS + IMAC) for 30 min. The aliquots in both experiment and control, were washed five times by centrifugation at 2000 g for 2 min in 0.5 ml of washing buffer, mixed with JEV at MOI = 1 (mannose + His-GRFT + IMAC + JEV or mannose + PBS + IMAC + JEV) for 1 h and incubated at a room temperature. The mixtures were then washed five times as above and the competitive binding of GRFT to JEV was measured by Pull-down assay using anti-JEV-EDIII monoclonal antibody (Ishag et al., 2013). To investigate the effect of mannose on viral infectivity, we preincubated GRFT (5 μg) or PBS (control) with increasing concentrations of mannose first and with JEV at MOI = 1 next. This mixture was then inoculated into BHK-21 cells. The inhibition of viral infectivity was analyzed by plaque forming assay as indicated previously (Ishag et al., 2013) and Western blot using anti-JEV-EDIII monoclonal antibody.

3. Statistical analysis

Data obtained from three individual experiments, were recorded as Mean ± SD, and subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS (version 16.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Constructs of pCDNA3.1 vector

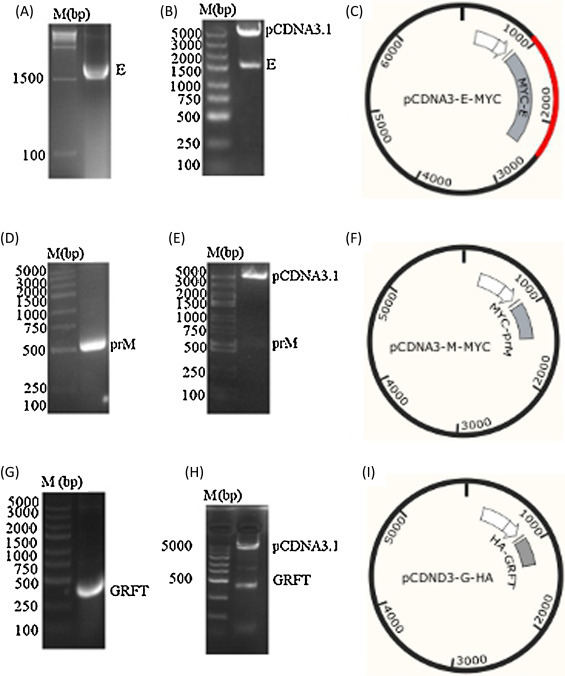

The MYC-tagged E, prM and HA-tagged GRFT genes were PCR amplified from the viral cDNA (Fig. 1 A,D and G) and cloned into pcDNA3.1 (+) vector to generate pcDNA3-E-MYC and pcDNA3-M-MYC and pcDNA3-G-HA (Fig. 1C,F and I) vectors respectively. The cloning was verified by restriction enzyme digestion of pcDNA3-E-MYC (BamHI and XbaI), pcDNA3-M-MYC (BamHI and XhoI) and pcDNA3-G-HA (KpnI and XbaI) (Fig. 1B,E and H) respectively and further confirmed by DNA sequencing analysis.

Fig. 1.

Constructs of the pcDNA3.1 (+) vectors. (A, D and G) are the PCR amplification of MYC-tagged E, prM and HA-tagged GRFT respectively. (B, E and H) are the enzymatic digestion of pcDNA3-E-MYC (BamHI and XbaI), pcDNA3-M-MYC (BamHI and XhoI) and pcDNA3-G-HA (KpnI and XbaI) respectively. (C, F and I) are the vectors pcDNA3-E-MYC, pcDNA3-M-MYC and pcDNA3-G-HA respectively.

4.2. GRFT specifically interacts with E and prM, analyzed Pulldown assay

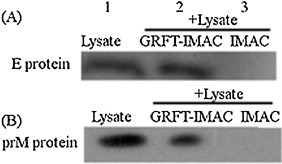

The specific interaction of GRFT with glycosylated viral proteins (E and prM) was investigated. The BHK-21 cells were transfected with pcDNA3-E-MYC or pcDNA3-M-MYC plasmids using empty pcDNA3.1 (+) vector as a control. Expression of E and prM proteins in these cells was first evaluated with anti-MYC monoclonal antibody. Pull-down assay was then performed from the lysate of E or prM-expressing cells. IMAC beads were first incubated with His-GRFT protein, washed and incubated with the cell lysate. The beads were washed and analyzed by Western blot using anti-MYC monoclonal antibody. As shown in (Fig. 2 A and B), E and prM proteins could only be detected in the cell lysates in the presence of GRFT protein, indicated that GRFT can interact with glycans presented on viral glycoproteins in vitro.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of specific interaction of GRFT with E and prM proteins in vitro by Pull-down assay: IMAC-beads were premixed with GRFT for 2 h and incubated with the lysate of BHK-21 cells expressing E protein (A) or prM protein (B) for another 2 h (Lane 2). The IMAC beads without GRFT was also incubated with the lysate of BHK-21 cells expressing E protein (A) or prM protein (B) for 2 h (Lane 3). The beads were washed and analyzed by Western blot using anti-MYC monoclonal antibody. The E and prM proteins in the cell lysates detected with anti-MYC monoclonal antibody served as a molecular mass marker (Lane 1).

4.3. GRFT interacts specifically with E and prM, analyzed by Co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP) assay

To investigate whether the interaction of GRFT with E and prM can occur in BHK-21 cells expressing these proteins, we performed a CO-IP assay using anti-HA monoclonal antibody. The lysate of cells co-expressing GRFT and E proteins or GRFT and prM proteins were incubated with protein G-Sepharose beads coupled with anti-HA monoclonal antibody for 2 h and were washed. The lysate of cells transfected with empty vector was used as a control. The beads were resuspended in 1 × SDS buffer and analyzed by Western blot using anti-MYC monoclonal antibody. GRFT together with E (Fig. 3 A) or prM (Fig. 3B) proteins could only be co-immunoprecipitated by anti-HA monoclonal antibody, indicating that GRFT can interact with E and prM glycosylated JEV proteins. Expression of GRFT protein in BHK-21 cells was first evaluated with anti-His monoclonal antibody.

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of specific interaction of GRFT with E and prM viral proteins in vivo by co-immunoprecipitation: (A and B) BHK-21 cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3-G-HA and pcDNA3-E-MYC or pcDNA3-G-HA and pcDNA3-M-MYC using Polyethylenimine (PEI). Cells transfected with empty vector used as control. At 24 h post-transfection, co-immunoprecipitation was performed form cell lysate using anti-HA monoclonal antibody. The immunoprecipitated protein was detected with anti-MYC monoclonal antibody (first panel in A and B). Cell lysates were evaluated using anti-MYC monoclonal antibody (second panel in A and B) and anti-HA monoclonal antibody (third panel in A and B) to detect the expression of E, prM and GRFT.

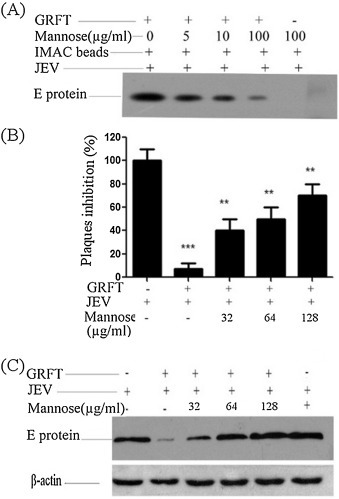

4.4. Competitive inhibition of GRFT binding by mannose and its effect on the viral infectivity

To investigate the specific binding of GRFT to the JEV glycosylated proteins, we performed a competitive assay using mannose as indicated in the materials and methods section. Pull-down assay using anti-JEV-EDIII monoclonal antibody indicated that pre-incubation of GRFT with mannose, decreased the binding ability of GRFT to the JEV (Fig. 4 A), and this inhibition was found to abolish the anti-JEV effect of GRFT (Fig. 4B and C), investigated by plaque forming assay and Western blot using anti-JEV-EDIII monoclonal antibody respectively. This indicates that, the specific binding of GRFT to the glycosylated JEV proteins might contribute to its anti-JEV activity.

Fig. 4.

Competitive inhibition of GRFT binding to the JEV by Mannose and its impact in viral infectivity: (A) mannose (5–100 μg/ml) was preincubated with 5 μg of His-GRFT ((Mannose + His-GRFT) or mannose (100 μg/ml) with PBS as a control (Mannose + PBS) for 30 min on a rocker and then added to 50 μl IMAC beads (Mannose + His-GRFT + IMAC or Mannose + PBS + IMAC) for 30 min. The aliquots in both experiment and control, were washed five times by centrifugation at 2000 g for 2 min in 0.5 ml of washing buffer, mixed with JEV at MOI = 1 (Mannose + His-GRFT + IMAC + JEV or Mannose + PBS + IMAC+ JEV) for 1 hr and incubated at a room temperature. The mixtures were then washed five times as above and the competitive binding of GRFT to JEV was measured by Pull-down assay using anti-JEV-EDIII monoclonal antibody. Binding of GRFT to the JEV was shown to be inhibited by increasing concentrations of mannose. (B and C) GRFT (5 μg) or PBS (control), were preincubated with different concentration of mannose and then with JEV at MOI = 1. BHK-21 cells were then infected with the mixture. Inhibition of the virus infection was analyzed by plaque forming assay (B) and Western blot using anti-JEV-EDIII monoclonal antibody (C). Data presented as Means ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

5. Discussion

There is currently no specific antiviral treatment available for the JEV infections. Interest of searching antiviral agent against JEV infection, has recently been encouraged. GRFT was one of the antiviral agents that showed activities against several enveloped viruses (O’Keefe et al., 2009a, O’Keefe et al., 2010a, Meuleman et al., 2011). The antiviral activity of the recombinant GRFT was found to be comparable to the native one (Giomarelli et al., 2006).

In our previous study, we observed that, the recombinant GRFT exhibited an anti-JEV activity. In the present study, we further aimed to elucidate the mechanism by which GRFT exerts its anti-JEV activity. As in other viruses such as SARS-CoV, HCV and HIV-1, it was found that GRFT binds to the glycosylated viral proteins to inhibit its infection. It is therefore likely that the anti-JEV activity of GRFT may be due to the binding of GRFT to the JEV glycosylated proteins (E and prM). To address this, we used an experimental approach of Pull-down assay and CO-IP assay. Our results showed that GRFT could bind to E and prM glycosylated JEV proteins, similar to its function in other viruses such as SARS-CoV, HCV and HIV-1. This binding activity of GRFT was found to be inhibited by increasing concentrations of mannose. As E protein in JEV is responsible for the virus attachment, fusion, penetration, cell tropism, virulence and attenuation (Lindenbach et al., 2007) while prM is important for the virus release and pathogenesis (Kim et al., 2008), we expect that, the virus inhibition observed, could be attributed to GRFT effect. It was shown that GRFT exists as a dimmer with six separate binding sites that bind to N-linked glycans on virus glycoproteins (Ziółkowska et al., 2006). Therefore, the interaction of GRFT with E and prM might inhibit the conformational change required for the virus–target cell attachment essential for viral entry and cell-to-cell fusion. However, this inhibition activity of GRFT was found to vary from virus to another and this was explained by the differences in the binding affinity of GRFT to the viral glycosylated proteins (O’Keefe et al., 2010b). This finding is in consistence with antiviral mechanisms of other lectins such as Cyanovirin-N (CV-N) that binds to the HIV-1 surface glycoprotein gp120 to inhibit its infection (Boyd et al., 1997).

In related studies, it was reported that, the interaction of GRFT with glycans on HIV-1 gp120, provides advantage by exposing the CD4 binding site (CD4bs) and increasing the chance to the CD4bs antibodies to bind to this site (Alexandre et al., 2011). Similarly, we also expect that, the conformational alteration caused by interaction of GRFT with JEV glycoproteins (Bressanelli et al., 2004) may expose the hidden epitopes of JEV glycoprotein, allowing the immune system to become actively involved in inhibiting the JEV infection (Balzarini, 2007).

GRFT compared to other antiviral lectins such as cyanovirin-N (CV-N) (Bolmstedt et al., 2001) and scytovirin (SVN) (Adams et al., 2004), demonstrated an ability to bind to a variety of oligosaccharides (Emau et al., 2007), providing a broad-spectrum antiviral activity against viruses. This indiscriminate activity of GRFT could be a challenge for the potential of GRFT as an antiviral agent. However, exhibiting activity against most threatening glycosylated viruses might also be considered as an advantage. In conclusion, this study further demonstrates a possible mechanism by which GRFT exerted its anti-JEV activity. It also indicated that GRFT might be a candidate for anti-JEV development.

Acknowledgment

This project was funded by the priority academic program development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

References

- Adams E.W., Ratner D.M., Bokesch H.R., McMahon J.B., O'Keefe B.R., Seeberger P.H. Chem. Biol. 2004;11:875–881. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre K.B., Gray E.S., Pantophlet R., Moore P.L., McMahon J.B., Chakauya E., O’Keefe B.R., Chikwamba R., Morris L. J. Virol. 2011;85:9039. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02675-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzarini J. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:583–597. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolmstedt A.J., O’Keefe B.R., Shenoy S.R., McMahon J.B., Boyd M.R. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;59:949–954. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd M.R., Gustafson K.R., McMahon J.B., Shoemaker R.H., O'Keefe B.R., Mori T., Gulakowski R.J., Wu L., Rivera M.I., Laurencot C.M. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1521–1530. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressanelli S., Stiasny K., Allison S.L., Stura E.A., Duquerroy S., Lescar J., Heinz F.X., Rey F.A. EMBO J. 2004;23:728–738. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C.-C., Lee S.-J., Chen Y.-S., Tsai H.-C., Wann S.-R., Kao C.-H., Liu Y.-C. Infection. 2007;35:30–32. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-6038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta K., Rangarajan P.N., Vrati S., Basu A. Curr. Sci. 2010;98:326. [Google Scholar]

- Emau P., Tian B., O’keefe B., Mori T., McMahon J., Palmer K., Jiang Y., Bekele G., Tsai C. J. Med. Primatol. 2007;36:244–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2007.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giomarelli B., Schumacher K.M., Taylor T.E., Sowder R.C., 2nd, Hartley J.L., McMahon J.B., Mori T. Protein Express. Purif. 2006;47:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishag H.Z., Li C., Huang L., Sun M.-x., Wang F., Ni B., Malik T., Chen P.-y., Mao X. Arch. Virol. 2013;158:349–358. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1489-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.M., Yun S.I., Song B.H., Hahn Y.S., Lee C.H., Oh H.W., Lee Y.M. J. Virol. 2008;82:7846. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00789-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Ge L.-l., Li P.-p., Wang Y., Dai J.-j., Sun M.-x., Huang L., Shen Z.-q., Hu X.-c., Ishag H. Virology. 2014;449:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenbach B.D., Thiel H.-J.U., Rice C.M. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Knipe D.M., Howley P.M., editors. Fields Virology. Lippincott-Raven; 2007. pp. 1108–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Meuleman P., Albecka A., Belouzard S., Vercauteren K., Verhoye L., Wychowski C., Leroux-Roels G., Palmer K.E., Dubuisson J. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5159–5167. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00633-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T., O’Keefe B.R., Sowder 2nd R.C., Bringans S., Gardella R., Berg S., Cochran P., Turpin J.A., Buckheit R.W., Jr., McMahon J.B., Boyd M.R. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:9345–9353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe B.R., Vojdani F., Buffa V., Shattock R.J., Montefiori D.C., Bakke J., Mirsalis J., d’Andrea A.-L., Hume S.D., Bratcher B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:6099–6104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901506106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe B.R., Vojdani F., Buffa V., Shattock R.J., Montefiori D.C., Bakke J., Mirsalis J., d'Andrea A.L., Hume S.D., Bratcher B. PNAS. 2009;106:6099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901506106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe B.R., Giomarelli B., Barnard D.L., Shenoy S.R., Chan P.K., McMahon J.B., Palmer K.E., Barnett B.W., Meyerholz D.K., Wohlford-Lenane C.L. J. Virol. 2010;84:2511–2521. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02322-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe B.R., Giomarelli B., Barnard D.L., Shenoy S.R., Chan P.K.S., McMahon J.B., Palmer K.E., Barnett B.W., Meyerholz D.K., Wohlford-Lenane C.L. J Virol. 2010;84:2511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02322-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumiyoshi H., Mori C., Fuke I., Morita K., Kuhara S., Kondou J., Kikuchi Y., Nagamatu H., Igarashi A. Virology. 1987;161:497–510. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumiyoshi H., Mori C., Fuke I., Morita K., Kuhara S., Kondou J., Kikuchi Y., Nagamatu H., Igarashi A. Virology. 1987;161:497–510. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziółkowska N.E., O'Keefe B.R., Mori T., Zhu C., Giomarelli B., Vojdani F., Palmer K.E., McMahon J.B., Wlodawer A. Structure. 2006;14:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziolkowska N.E., O'Keefe B.R., Mori T., Zhu C., Giomarelli B., Vojdani F., Palmer K.E., McMahon J.B., Wlodawer A. Structure. 2006;14:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]