Highlights

-

•

We sequenced the genome of several canine astroviruses.

-

•

Genetic heterogeneity was detected among strains.

-

•

A novel strain related to mink astrovirus was identified.

Keywords: Astroviridae, Dog, Semiconductor sequencing, Hungary

Abstract

Canine astrovirus RNA was detected in the stools of 17/63 (26.9%) samples, using either a broadly reactive consensus RT-PCR for astroviruses or random RT-PCR coupled with massive deep sequencing. The complete or nearly complete genome sequence of five canine astroviruses was reconstructed that allowed mapping the genome organization and to investigate the genetic diversity of these viruses. The genome was about 6.6 kb in length and contained three open reading frames (ORFs) flanked by a 5′ UTR, and a 3′ UTR plus a poly-A tail. ORF1a and ORF1b overlapped by 43 nucleotides while the ORF2 overlapped by 8 nucleotides with the 3′ end of ORF1b. Upon genome comparison, four strains (HUN/2012/2, HUN/2012/6, HUN/2012/115, and HUN/2012/135) were more related genetically to each other and to UK canine astroviruses (88–96% nt identity), whilst strain HUN/2012/126 was more divergent (75–76% nt identity). In the ORF1b and ORF2, strains HUN/2012/2, HUN/2012/6, and HUN/2012/135 were related genetically to other canine astroviruses identified formerly in Europe and China, whereas strain HUN/2012/126 was related genetically to a divergent canine astrovirus strain, ITA/2010/Zoid. For one canine astrovirus, HUN/2012/8, only a 3.2 kb portion of the genome, at the 3′ end, could be determined. Interestingly, this strain possessed unique genetic signatures (including a longer ORF1b/ORF2 overlap and a longer 3′UTR) and it was divergent in both ORF1b and ORF2 from all other canine astroviruses, with the highest nucleotide sequence identity (68% and 63%, respectively) to a mink astrovirus, thus suggesting a possible event of interspecies transmission. The genetic heterogeneity of canine astroviruses may pose a challenge for the diagnostics and for future prophylaxis strategies.

1. Introduction

Astroviruses (AstV), family Astroviridae, are non-enveloped viruses with a diameter of 28–30 nm and with a typical star-like shape. The genome is a single strand of positive sense, RNA of 6.4-7.3 kb in size, containing three overlapping ORFs (ORF1a, ORF1b and ORF2) with a 3′ poly(A) tail (Mendez and Arias, 2007). ORF1a encodes a serine 3C type of viral protease. ORF1b is separated from ORF1a by a heptameric frame shift signal (AAAAAAC) and encodes the viral RNA polymerase. ORF2 encodes an 87-kDa polypeptide, which functions as the capsid precursor. AstV infection is associated with gastroenteritis in many animal species and humans, and they are also associated with extra-intestinal diseases, such as nephritis in chickens, hepatitis in ducks and shaking syndrome in minks (Imada et al., 2000, Fu et al., 2009, Blomström et al., 2010). The evolution of AstVs is driven by mechanisms of genetic drift, recombination and, possibly, inter-species transmission (Finkbeiner et al., 2008, De Benedictis et al., 2011, Martella et al., 2014).

So far, AstVs are classified into two distinct genera, Mamastrovirus (MAstV) and Avastrovirus (AvAstV) with 19 MAstV (mammalian) species and 3 AvAstV (avian) species listed officially by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) (Bosch et al., 2010). However, taking advantage of broad-range PCR primers for AstVs and metagenomic protocols, several novel AstVs have been identified in a number of mammalian and avian species (Chu et al., 2008, Finkbeiner et al., 2008, Bosch et al., 2010, De Benedictis et al., 2011). Using the classification criteria adopted in the 9th ICTV report that is based on genetic analysis of the full-length ORF2, an additional 14 MAstV and 4 AvAstV candidate species have been defined recently (Schultz-Cherry, 2013).

AstV-like particles have been detected only occasionally in dogs by EM, either alone or in co-infection with other enteric viruses (Williams, 1980, Marshall et al., 1984, Vieler and Herbst, 1995, Toffan et al., 2009). More recently, AstVs have been identified in dogs with enteric signs and characterized molecularly, suggesting that the detected viruses may represent a distinct AstV species (Toffan et al., 2009). Also, a canine AstV, strain ITA/08/Bari, was successfully adapted to replicate in vitro on MDCK cells, and AstV-specific antibodies were detected in convalescent canine sera (Martella et al., 2011a, Martella et al., 2011b, Martella et al., 2012). The prevalence of AstV infection seems higher in dogs with enteric disease than in asymptomatic animals (Martella et al., 2011a, Martella et al., 2011b, Zhu et al., 2011, Caddy and Goodfellow, 2015, Takano et al., 2015). Also, monitoring of natural infection by AstV in dogs has revealed that the acute phase of gastroenteritis overlaps with peaks of viral shedding (Martella et al., 2012). At present, limited and partial information on canine AstV genomes is available in GenBank. This limited amount of information seems to suggest that canine AstVs are genetically heterogeneous (Martella et al., 2011a, Martella et al., 2011b, Caddy and Goodfellow, 2015), thus posing a challenge for the diagnostic and for the understanding of the genetic and biological properties of these viruses in dogs.

In this study, the complete or nearly complete genome sequence of five canine AstVs and the partial genome sequence of one canine AstV were determined and analysed, providing information on the genome organization and genetic diversity of these viruses.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Samples

During 2012 samples were collected from diarrheic and non-diarrheic dogs from a Hungarian shelter. There was no age restriction. A total of 63 samples obtained from 50 animals were tested for AstV by using a pan-astrovirus specific primer set (Chu et al., 2008) as described elsewhere (Mihalov-Kovács et al., 2014) and 37 (from 33 dogs) were randomly selected for viral metagenomics.

Fecal samples were diluted 1: 10 in PBS (phosphate buffered saline) and homogenized. The homogenates were centrifuged at 10000g for 5 min and the supernatant was collected for extraction of viral RNA (Zymo DirectZol viral RNA extraction kit, Zymo Research).

2.2. Semiconductor sequencing

Templates for deep sequencing were prepared as described previously (Mihalov-Kovács et al., 2015). In brief, viral RNA samples were denatured at 97 °C for 5 min in the presence of 10 μM random hexamer tailed by a common PCR primer sequence (Djikeng et al., 2008). Reverse transcription was performed with 1 U AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), 400 μM dNTP mixture, and 1× AMV RT buffer at 42 °C for 45 min following a 5 min incubation at room temperature. Then, 5 μL cDNA was added to 45 μL PCR mixture to obtain a final volume of 50 μL and a concentration of 500 μM for the PCR primer, 200 μM for dNTP mixture, 1.5 mM for MgCl2, 1 × Taq DNA polymerase buffer, and 0.5 U for Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania). The reaction conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 30 s, 48 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 2 min) and terminated at 72 °C for 8 min.

We subjected 0.1 μg of random PCR product to enzymatic fragmentation and adaptor ligation (NEBNext Fast DNA Fragmentation & Library Prep Set for Ion Torrent kit, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). The barcoded adaptors were retrieved from the Ion Xpress Barcode Adapters (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The resulting cDNA libraries were measured on an Qubit 2.0 device using the Qubit dsDNA BR Assay kit (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA). The emulsion PCR that produced clonally amplified libraries was carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the Ion PGM Template kit on an OneTouch v2 instrument. Enrichment of the templated beads (on an Ion One Touch ES machine) and further steps of presequencing setup were performed according to the Page 3 of 11 200-bp protocol of the manufacturer. The sequencing protocol recommended for Ion PGM Sequencing Kit on an 316 chip was strictly followed.

2.3. 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (5′ RACE)

To determine the actual 5′ end genomic sequence of two AstV strains, a 5′ RACE protocol was used, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen Ltd). The amplicons were visualized on 1.5% agarose gel, and cleaned up with Qiagen Qiaquick Gel Extraction Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The amplicons were cloned using TOPO XL PCR Cloning (Invitrogen Ltd) and the clones were subjected to sequencing in both directions using Big Dye v3.1 chemistry on a 3730xl instrument from Applied Biosystems (Foster, CA). For sequencing accuracy, a minimum of three independent clones for each fragment type were selected for sequencing in both directions using the universal M13F/R primers.

2.4. 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (3′ RACE)

The First Strand III kit (Invitrogen Ltd) was used to generate cDNA from the poly-A tailed RNA target, as described previously (Martella et al., 2011a, Martella et al., 2011b). Forward primers were designed about 1 kb upstream of the 3′ terminus of the genome of the various AstV strains and used with a reverse poly-T oligonucleotide with a 5′-anchored tail. The 3′ RACE products were sequenced on Ion Torrent PGM.

2.5. Sequence and phylogenetic analysis

Sequence data generated by the Ion Torrent PGM were trimmed and analysed by the CLC Bio software (www.clcbio.com). The same software package was utilized to map sequence reads to reference eucaryotic viral sequences retrieved from GenBank. Sequence editing, annotation and analysis were carried out using Geneious software v9.1.4 (Biomatters LTD, New Zealand). Open reading frames (ORF) were predicted with the ORF finder. Multiple alignments were prepared and manually adjusted, whereas phylogenetic analysis was performed by using the MEGA6 software (Tamura et al., 2013) with a neighbor-joining method, Jukes Cantor genetic distance model and bootstrapping over 1000 replicates. Mean amino acid genetic distances were computed using the p-distance method of MEGA6. The protein sequence analysis and classification were prepared with the aid of EMBL-EBI website (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/). Transmembrane domains were determined using Phobius web server (Käll et al., 2007). Nuclear localization signals (NLS) were predicted by http://www.moseslab.csb.utoronto.ca/NLStradamus/.

2.6. GenBank accession numbers

AstV genomic sequences were deposited in the GenBank with the following accession numbers: HUN/2012/2, KX599349; HUN/2012/6, KX599350; HUN/2012/115, KX599351; HUN/2012/126, KX599352; HUN/2012/135, KX599353; HUN/2012/8, KX599354.

3. Results

3.1. Detection of AstV sequences in the canine fecal virome

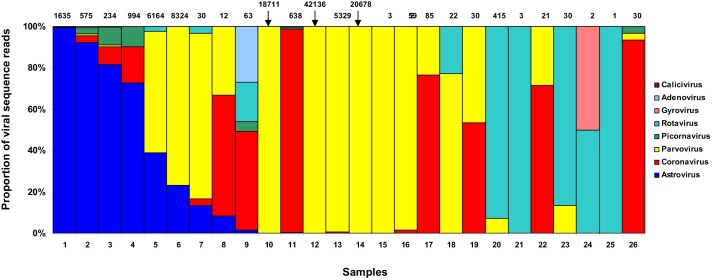

During 2012, 63 stool specimens were screened for AstVs using broad-range AstV-specific primer set. Of these, seven tested positive; 4 out of 25 diarrheic animals (16%) and 3 out of 38 non-diarrheic animals (8%). The difference between groups was not statistically significant (chi-square value, 1.003; p = 0.316). A subset (n = 37) of samples was selected from 33 animals for viral metagenomics to detect virus diversity in canine fecal specimens. Among these 37 samples 26 specimens contained eukaryotic origin viral sequences (Fig. 1 ). By viral metagenomics (Table 1 ), AstV RNA was initially identified in 11 out of 37 fecal specimens (29.7%). However, the proportion of AstV specific reads ranged from 1 out of 18711 ( < 0.1%) to 1627 out of 1635 (99.5%) eukaryotic viral sequence reads, respectively, and five samples that had very low AstV sequence read numbers (range, 1–4) were not considered for further processing. Other enteric viruses detected in the stools included parvovirus (in 20 samples), coronavirus (in 14 samples), rotavirus (in 11 samples), picornavirus (in 7 samples), gyrovirus (in 1 sample), adenovirus (in 1 sample) and calicivirus (in 1 sample). Overall, by either the pan-astrovirus RT-PCR or by the viral metagenomic screening, we identified AstV RNA in 17/63 (26.9%) samples. Interestingly, some samples negative in RT-PCR generated AstV-specific reads by deep sequencing, whilst, in turn, some samples containing AstV-specific reads tested negative by the pan-astrovirus RT-PCR, indicating a weak correlation between the two methodologies (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of eukaryotic viral sequences in 26 fecal specimens collected from sheltered dogs. The numbers of virus-specific reads are indicated above the columns.

Table 1.

Origin and information on canine stool samples positive for AstV by broad-range RT-PCR and viral metagenomics.

| Sample name | Date of sampling | Age of dog | Diarrheic symptoms | Screening by pan-astrovirus PCR | AstV reads by metagenomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUN/2012/2 | 20/01/2012 | 5 weeks | Yes | Positive | 723 |

| HUN/2012/4 | 26/01/2012 | 5 weeks | Yes | Positive | 0 |

| HUN/2012/5 | 30/01/2012 | 3 months | Yes | Positive | 0 |

| HUN/2012/6 | 03/02/2012 | 8 years | No | Negative | 191 |

| HUN/2012/8 | 10/02/2012 | 4 months | Yes | Positive | 0 |

| HUN/2012/22 | 17/02/2012 | 3 months | No | Negative | 4 |

| HUN/2012/14 | 09/03/2012 | Pool of 3 adults | No | Positive | 0 |

| HUN/2012/16 | 09/03/2012 | Pool of 2 adults | No | Positive | 0 |

| HUN/2012/114 | 15/04/2012 | 6 years | No | Negative | 1 |

| HUN/2012/115 | 20/04/2012 | 6 months | Yes | Negative | 1922 |

| HUN/2012/116 | 20/04/2012 | 1 year | Yes | Negative | 1 |

| HUN/2012/126 | 27/04/2012 | under one year | No | Negative | 1627 |

| HUN/2012/135 | 09/05/2012 | 3 weeks | No | Negative | 2398 |

| HUN/2012/175 | 05/06/2012 | 6 weeks | No | Positive | 531 |

| HUN/2012/527 | 23/08/2012 | 1 year | Yes | Negative | 1 |

| HUN/2012/528 | 07/09/2012 | 2 year | Yes | Negative | 1 |

3.2. General features of the canine AstV genomes

For further analysis the complete, coding complete and partial genome sequence was determined for four, one and one AstV strains, respectively. In general, the length of the coding sequences ranged between 6441 and 6474 nucleotide (nt), with a GC content of 45.19-45.48%. The total genome length, considering the 5′ and 3′ UTRs, ranged between 6535 and 6587 nt. The 5′ UTR was sequenced completely for strains HUN/2012/2, HUN/2012/115, HUN/2012/126 and HUN/2012/135, and ranged between 42 and 60 nt in length. The 3′ UTR was sequenced completely for all the six strains and ranged between 49 and 100 nt in length.

The genome of strain HUN/2012/115 was 6569 nt long, excluding the polyA-tail. The 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR were, respectively, 45 nt and 83 nt long. The genome of strain HUN/2012/135 was 6587 nt long and it was organized similarly to strain HUN/2012/115, even if the 3′ UTR was 2 nt longer. The genome of strain HUN/2012/2 was 6576 nt long and it differed for the longer 5′ UTR region (60 nt) from the other canine AstVs. Despite several attempts, for strain HUN/2012/6, it was not possible to generate the actual 5′ UTR sequence. The genome of this strain was organized in an identical manner to the canine AstV strain GBR/2014/Gillingham. The genome length of the AstV strain HUN/2012/126 was 6535 nt long, excluding the polyA-tail. The 5′ UTR was 42 nt in length, with an additional in-frame ATG codon located 18 nt upstream (bases 25–27) of the ATG codon of ORF1. The 3′ UTR was 49 nt long. Only the partial genome (3187 nt in length) of strain HUN/2012/8 was determined. The virus possessed an early stop codon in the ORF2, resulting in a longer (100 nt) 3′ UTR (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Genomic features of canine AstVs.

| Name | 5′UTR | ORF1a | ORF1b | 1a/1b | ORF2 | 1b/2 | 3′UTR | Sequence lenght | Accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUN/2012/8 | – | – | 770a | – | 2328/2469 | 11/152 | 100 | 3187a | KX599354 |

| HUN/2012/2 | 60 | 2670 | 1530 | 43 | 2295/2475 | 8/188 | 83 | 6587 | KX599349 |

| HUN/2012/6 | 19a | 2670 | 1530 | 43 | 2325/2505 | 8/188 | 83 | 6576a | KX599350 |

| HUN/2012/115 | 45 | 2670 | 1530 | 43 | 2292/2472 | 8/188 | 83 | 6569 | KX599351 |

| HUN/2012/126 | 24/42b | 2667/2685c | 1530 | 43 | 2298/2478 | 8/188 | 49 | 6535 | KX599352 |

| HUN/2012/135 | 45 | 2670 | 1530 | 43 | 2292/2472 | 8/188 | 85 | 6571 | KX599353 |

| GBR/2014/Gillingham | 45 | 2670 | 1530 | 43 | 2325/2505§ | 8/188 | 83 | 6600 | KP404149 |

| GBR/2014/Lincoln | 45 | 2670 | 1530 | 43 | 2295/2475 | 8/188 | 81 | 6572 | KP404150 |

| GBR/2014/Huntingdon | – | – | 188a | – | 2295/2475 | – | – | 2475a | KP404151 |

| GBR/2014/Braintree | – | – | 188a | – | 2298/2478 | – | – | 2478a | KP404152 |

| ITA/2008/Bari | – | – | 716a | – | 2325/2505 | 8/188 | 87 | 3120a | HM045005 |

| ITA/2010/Zoid | – | – | 582a | – | 2298/2478 | 8/188 | 77 | 2949a | JN193534 |

| ITA/2005/3 | – | – | 356a | – | 2325/2505 | 8/188 | 83 | 2756a | FM213330 |

| ITA/2005/6 | – | – | 187a | – | 2322/2501 | – | 83 | 2584a | FM213332 |

| ITA/2005/8 | – | – | 354a | – | 2325/2505 | 8/188 | 83 | 2754a | FM213331 |

| CHN/2008/SH8 | – | – | 442a | – | 2295/2475 | 8/188 | 9a | 2738a | HQ623147 |

| CHN/2008/SH15 | – | – | 442a | – | 2295/2475 | 8/188 | 9a | 2738a | HQ623148 |

| CHN/2009/SH | – | – | 445a | – | 2295/2475 | 8/188 | 12a | 2744a | GU376736 |

| CHN/2012 | – | 1198a | 1530 | 49 | 2295/2475 | 8/188 | 39a | 5011a | JQ081297 |

For the ORF1a and ORF2, the ORF length is calculated considering the presence of an additional start codon. This value is also calculated for the ORF1b/ORF2 overlap.

Partial sequence.

An additonal ATG codon is present 18 nt upstream (bases 25–27) of the ORF1a initiation codon.

Based on the additional ORF1a start codon, the ORF1a-predicted polyprotein could be 6 aa longer; –not available.

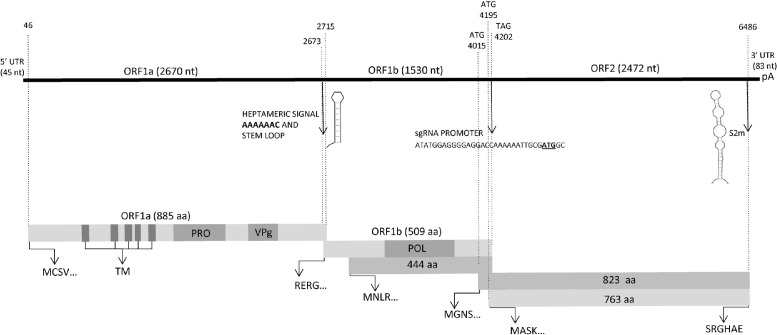

The coding sequences showed the typical organization of AstV genome. There were three overlapping ORFs, coding the non-structural and structural proteins. The predicted genome organization of the viruses is shown in Fig. 2 and summarized in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the genome of canine AstV strain HUN/2012/115. The upper line represents the complete nt length of the genome from the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) through the 3′ UTR and the poly-A tail (pA). The relative position of the slippery sequence AAAAAAC and downstream stem loop structure is indicated. Also, the position of the subgenomic RNA (sgRNA) promoter and of the stem loop-II-like (s2m) structure are indicated. Rectangles represent the three possible open reading frames (ORFs) (light grey) and the alternate ORF1b and ORF2 products due to in-frame start codons (dark grey). The starting aa motifs of the various ORFs and the ending aa motif of ORF2 are marked. The potential trans-membrane regions (TM), the predicted protease motif (PRO), the genome-linked protein (VPg) and the polymerase region (POL) are also shown.

3.3. Analysis of ORF1a

The complete ORF1a was 2670 nt long for all canine AstVs, except strain HUN/2012/126, and codes for a 889 aa long polyprotein. For strain HUN/2012/126, an in-frame start codon is located 18 nt upstream of the ORF1 start codon (the length of the ORF is 2667/2685 depending on the start). A ribosomal frameshift signal, the heptameric (slippery) AAAAAAC sequence, was recognized at nt 2622–2628 (2619/2637 in HUN/2012/126 depending on the start used), with the ORF1b initiating after the slippery sequence. The predicted 95 kDa nsp1a protein, encoded by ORF1a, contained conserved domains typical for the AstV serine protease between aa 439 and 583 aa. Five transmembrane domains were identified on the predicted ORF1a protein at residues aa151-168, aa240-266, aa287-313, aa319-339 and aa351-380. A possible coiled coil structure was also found at residues aa595-616 and aa635-656 (Fig. 2).

Upon sequence comparison, strains HUN/2012/2, HUN/2012/6, HUN/2012/115 and HUN/2012/135 displayed 96–99% nt identity to each other and 93–98% nt to the canine strains UK/2014/Lincoln and UK/2014/Gillingham, whilst strain HUN/2012/126 displayed only 74% nt identity to the other canine AstVs. Identity to non-canine AstVs was markedly lower (33–51% nt) (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Sequence comparison among canine AstVs and closely related AstV strains.

| Species | Dog/HUN/2012/2 |

Dog/HUN/2012/6 |

Dog/HUN/2012/8 |

Dog/HUN/2012/115 |

Dog/HUN/2012/126 |

Dog/HUN/2012/135 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1a |

ORF1b |

ORF2 |

ORF1a |

ORF1b |

ORF2 |

ORF1a |

ORF1b |

ORF2 |

ORF1a |

ORF1b |

ORF2 |

ORF1a |

ORF1b |

ORF2 |

ORF1a |

ORF1b |

ORF2 |

|||||||||||||

| nt | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | nt | aa | nt | aa | |

| Dog/GBR/2014/Lincoln-KP404150 | 94 | 99 | 99 | 95 | 99 | 93 | 99 | 99 | 79 | 79 | – | 57 | 51 | 35 | 22 | 93 | 98 | 99 | 75 | 77 | 74 | 86 | 88 | 74 | 76 | 94 | 99 | 99 | 91 | 95 |

| Dog/GBR/2014/Gillingham-KP404149 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 74 | 78 | 97 | 99 | 99 | 95 | 98 | – | 57 | 51 | 34 | 23 | 96 | 98 | 99 | 75 | 76 | 74 | 86 | 88 | 74 | 77 | 98 | 99 | 99 | 77 | 79 |

| Dog/UK/2014/Huntingdon-KP404151 | – | – | – | 74 | 77 | – | – | – | 78 | 80 | – | – | – | 35 | 23 | – | – | – | 75 | 80 | – | – | – | 79 | 88 | – | – | – | 78 | 79 |

| Dog/UK/2014/Braintree-KP404152 | – | – | – | 79 | 86 | – | – | – | 76 | 78 | – | – | – | 35 | 23 | – | – | – | 73 | 75 | – | – | – | 73 | 75 | – | – | – | 84 | 88 |

| Dog/ITA/2005/3- FM213330 |

– | 97 | 99 | 74 | 79 | – | 97 | 99 | 92 | 97 | – | 58 | 51 | 34 | 23 | – | 97 | 99 | 75 | 76 | – | 85 | 88 | 74 | 77 | – | 98 | 99 | 77 | 79 |

| Dog/ITA/2005/6- FM213332 |

– | – | – | 74 | 77 | – | – | – | 91 | 96 | – | – | – | 34 | 23 | – | – | – | 75 | 76 | – | – | – | 74 | 76 | – | – | – | 76 | 78 |

| Dog/ITA/2005/8-FM213331 | – | 97 | 99 | 74 | 78 | – | 97 | 99 | 92 | 98 | – | 57 | 51 | 34 | 23 | – | 96 | 99 | 75 | 76 | – | 86 | 88 | 74 | 77 | – | 97 | 99 | 77 | 79 |

| Dog/ITA/2008/Bari-HM045005 | – | 96 | 99 | 76 | 83 | – | 96 | 99 | 80 | 83 | – | 58 | 51 | 35 | 22 | – | 96 | 99 | 72 | 74 | – | 86 | 87 | 70 | 73 | – | 97 | 99 | 77 | 84 |

| Dog/ITA/2010/Zoid-JN193534 | – | 86 | 88 | 72 | 76 | – | 86 | 88 | 73 | 77 | – | 56 | 50 | 35 | 23 | – | 85 | 88 | 79 | 79 | – | 99 | 99 | 97 | 98 | – | 86 | 88 | 74 | 78 |

| Dog/CHN/2008/SH8-HQ623147 | – | 97 | 99 | 96 | 98 | – | 97 | 99 | 79 | 79 | – | 57 | 51 | 35 | 22 | – | 97 | 99 | 74 | 76 | – | 85 | 88 | 73 | 75 | – | 97 | 99 | 91 | 95 |

| Dog/CHN/2008/SH15-HQ623148 | – | 97 | 99 | 96 | 99 | – | 97 | 99 | 79 | 79 | – | 57 | 52 | 35 | 22 | – | 97 | 99 | 74 | 76 | – | 85 | 88 | 74 | 75 | – | 97 | 99 | 91 | 95 |

| Dog/CHN/2009/SH-GU376736 | – | 96 | 99 | 96 | 99 | – | 96 | 99 | 79 | 79 | – | 56 | 53 | 36 | 22 | – | 96 | 99 | 74 | 77 | – | 81 | 84 | 74 | 76 | – | 96 | 99 | 91 | 96 |

| Dog/CHN/2012-JQ081297 | – | 96 | 99 | 96 | 99 | – | 97 | 99 | 79 | 79 | – | 57 | 51 | 36 | 22 | – | 97 | 99 | 74 | 77 | – | 86 | 88 | 74 | 76 | – | 97 | 99 | 91 | 96 |

| Fe/HK/2012/1637F-KF499111 | 47 | 75 | 78 | 42 | 33 | 47 | 74 | 78 | 42 | 33 | – | 57 | 52 | 32 | 20 | 47 | 75 | 78 | 41 | 32 | 46 | 74 | 76 | 40 | 33 | 47 | 75 | 78 | 42 | 33 |

| Mink/SWE/2003-AY179509 | 33 | 54 | 41 | 35 | 23 | 33 | 54 | 50 | 35 | 24 | – | 67 | 69 | 63 | 64 | 33 | 53 | 42 | 35 | 22 | 32 | 54 | 51 | 35 | 22 | 33 | 54 | 41 | 36 | 24 |

| CSL/USA/2006/CSL1-FJ890351 | – | 54 | 49 | 35 | 21 | – | 54 | 49 | 34 | 21 | – | 65 | 67 | 58 | 55 | – | 54 | 49 | 33 | 20 | – | 53 | 45 | 34 | 21 | – | 54 | 49 | 35 | 21 |

| Dog/HUN/2012/2 | / | / | / | / | / | 96 | 99 | 99 | 79 | 79 | – | 58 | 51 | 35 | 22 | 96 | 98 | 99 | 74 | 76 | 74 | 86 | 88 | 72 | 75 | 97 | 99 | 99 | 92 | 96 |

| Dog/HUN/2012/6 | 96 | 99 | 99 | 79 | 79 | / | / | / | / | / | – | 57 | 51 | 34 | 23 | 98 | 98 | 99 | 75 | 76 | 74 | 86 | 88 | 74 | 76 | 97 | 99 | 99 | 78 | 78 |

| Dog/HUN/2012/8 | – | 58 | 51 | 35 | 22 | – | 57 | 51 | 34 | 23 | – | / | / | / | / | – | 57 | 51 | 34 | 22 | – | 56 | 50 | 34 | 23 | – | 57 | 51 | 35 | 23 |

| Dog/HUN/2012/115 | 96 | 98 | 99 | 74 | 76 | 98 | 98 | 99 | 75 | 76 | – | 57 | 51 | 34 | 22 | / | / | / | / | / | 74 | 85 | 88 | 79 | 78 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 74 | 77 |

| Dog/HUN/2012/126 | 74 | 86 | 88 | 72 | 75 | 74 | 86 | 88 | 74 | 76 | – | 56 | 50 | 34 | 23 | 74 | 85 | 88 | 79 | 78 | / | / | / | / | / | 74 | 86 | 88 | 75 | 77 |

| Dog/HUN/2012/135 | 97 | 99 | 99 | 92 | 96 | 97 | 99 | 99 | 78 | 78 | – | 57 | 51 | 35 | 23 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 74 | 77 | 74 | 86 | 88 | 75 | 77 | / | / | / | / | / |

Sequence identity among the canine astroviruses analysed in this study and other canine and mammalian astroviruses in the full-length ORF1a, partial ORF1b (RdRp) and full-lenght ORF2 (capsid) regions. The values of RdRp comparison were calculated using a 3′ fragment of 415 nt (138 aa) of the ORF1b.

3.4. Analysis of ORF1b

The complete ORF1b was 1530 nt long in all canine AstVs, except the partially sequenced strain, HUN/2012/8, where a 770 nt long portion was determined. The ORF1b begins with the last nucleotide of the slippery heptamer and with a −1 frameshift with respect to ORF1a. Also, the downstream stem loop structure was highly conserved among canine AstVs (Caddy and Goodfellow, 2015). ORF1b codes for a 509 aa long non-structural protein, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). The RdRp domain was recognized between aa168-373, with conserved motifs at positions aa321 (GNPSG), aa364 (YGDD), and aa391 (FGMWVK).

Sequence comparison in the ORF1b (RdRp) was calculated using a 415 nt (138 aa) long fragment located at the very 3′ end of the gene. Upon sequence comparison, strains HUN/2012/2, HUN/2012/6, HUN/2012/115 and HUN/2012/135 displayed 98–99% nt (99% aa) identity to each other and 96–99% nt (99% aa) to most canine strains. Strain HUN/2012/126 displayed the highest identity to strain ITA/2010/Zoid (99% nt and 99% aa) and 85–86% nt (87–88% aa) to the other canine AstVs. Strain HUN/2012/8 displayed the highest identity to a mink AstV (68% nt and 70% aa), whilst identity to other canine AstVs was lower (56–58% nt and 50–52% aa) (Table 3).

3.5. Analysis of ORF2

The length of ORF2 is variable among the canine AstV strains. In all but one strains analysed in this study, the ORF1b and ORF2 overlapped by 8 nt. In strain HUN/2012/8 the overlapping was 11 nt in length. In addition, there was a second in-frame ATG start codon, located 180 nt upstream of the start codon homologous to other Mamastrovirus genomes. Only in strain HUN/2012/8, this additional in-frame start codon was located 141 nt upstream of the first start codon. During the RNA replication, ORF2 is expressed from a sgRNA (Walter and Mitchell, 2003, Mendez et al., 2014). The sgRNA promoter sequence has a highly conserved nucleotide sequence motif and is present upstream of the ORF2 start codon (Mendez et al., 2014). The highly conserved nucleotide stretch upstream of ORF2, ATATGGAGGGGAGGACCAAAAAATTGCGATGGC, believed to be part of a promoter region for synthesis of sgRNA, was completely conserved in the sequence of canine AstV strains except for the sequence of strain HUN/2012/8, that was CTTTGGAGGGGAGGACCAAAGCAGCGCTATGGC.

The ORF2 was 2292/2472 nt long for strain HUN/2012/115 and HUN/2012/135, 2295/2475 nt long for strain HUN/2012/2, 2325/2505 nt long for strain HUN/2012/6, 2298/2478 nt for strain HUN/2012/126 and 2328/2469 nt for HUN/2012/8 (Table 2). The terminal nt stretch of ORF2 and the adjacent 3′UTR (s2m) is highly conserved among most AstVs and similarities have been observed in the sequence and folding of the 3′UTR of viruses from other viral families, suggesting that it is relevant for AstV genome replication (Monceyron et al., 1997). The conserved s2 m sequence CCGCGGCCACGCCGAGTAGGAACGAGGGTACAG overlaps the 6 aa C terminus of the capsid (SRGHAE), that is highly conserved in several mammalian AstVs, including the canine AstVs (Fig. 2). However, in strain HUN/2012/8 the highly conserved s2m stretch was found downstream of the ORF2 termination codon, in the 3′UTR. As a consequence, the 6 aa C terminus of strain HUN/2012/8 was TLSTKH.

Upon sequence comparison, the Hungarian canine AstVs were found to differ markedly. Strains HUN/2012/2 and HUN/2012/135 were highly related to each other (92% nt and 96% aa identity) and to Chinese CAstVs (91–96% nt and 95–99% aa identity) as well as to the UK strain GBR/2014/Lincoln (91–95% nt and 95–99% aa). Strain HUN/2012/6 displayed the highest identity (91–95% nt and 96–98% aa) to three Italian strains (ITA/2005-3, ITA/2005-6, ITA/2005-8) and to the UK strain GBR/2014/Gillingham. Strain HUN/2012/126 displayed the highest identity (97% nt and 98% aa) to the Italian strain ITA/2010/Zoid. Strain HUN/2012/115 displayed the highest identity (79% nt and 79% aa) to the Italian strain ITA/2010/Zoid, while sequence identity to other canine AstVs ranged from 72 to 75% at the nt level and 75–80% at the aa level. Interestingly, strain HUN/2012/8 displayed the highest identity (63% nt and 64% aa) to a mink AstV (Table 3).

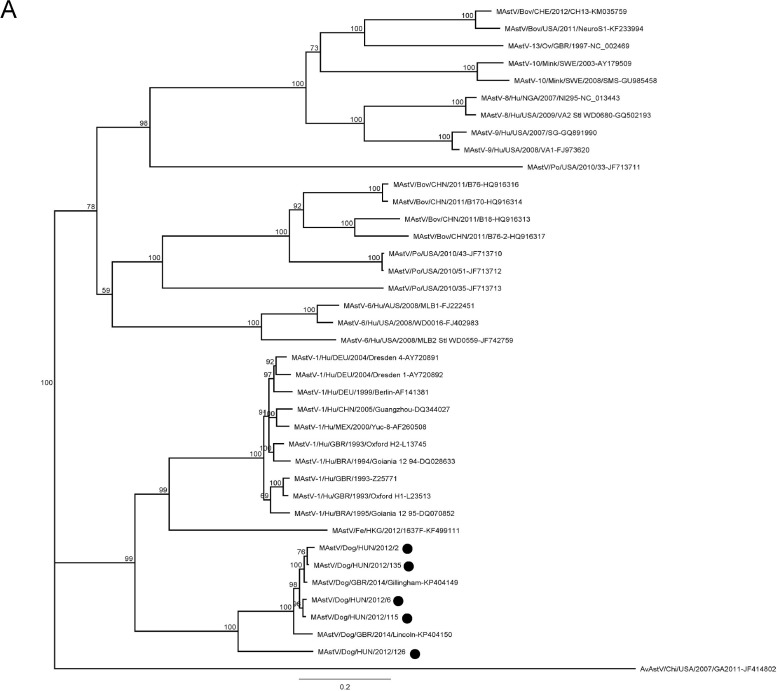

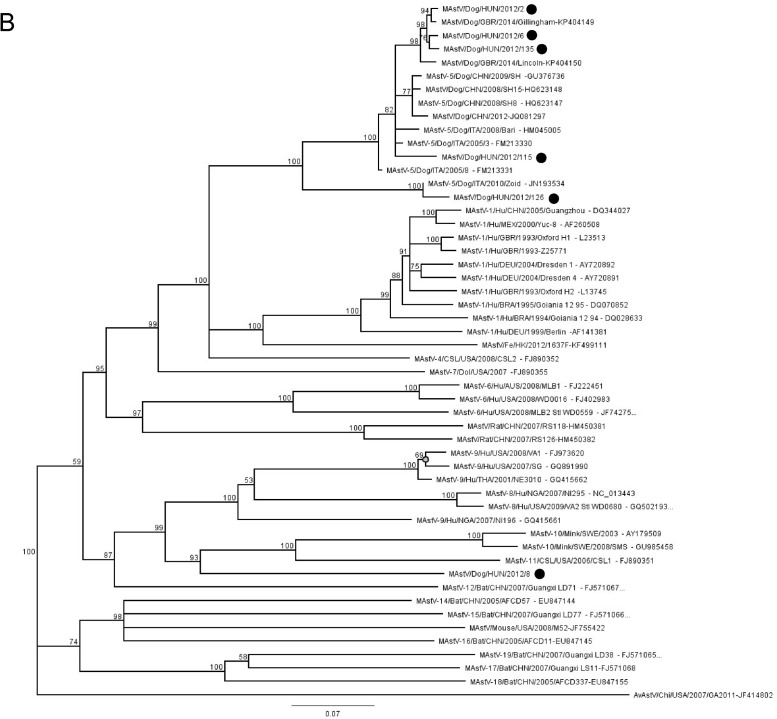

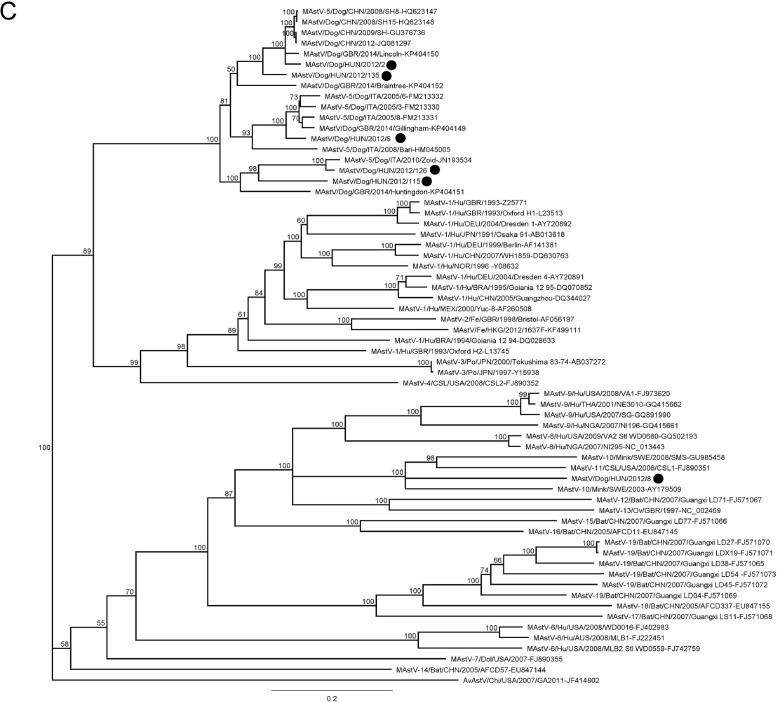

3.6. Phylogenetic analysis of canine AstVs

Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the nucleotide alignments of ORF1a, ORF1b and ORF2 (Fig. 3 ). The ORF1a and ORF2 alignments were based on the full-length ORF sequences and also included a selection of sequences of mammalian AstV strains. The ORF1b alignment included 415 nt at the 3′ end (138 aa at the C terminus of the protein).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic trees based on the full-length ORF1a (3A), ORF1b (3B) and ORF2 (3C) of canine AstVs with a selection of mammalian AstVs. The tree was generated using the neighbor-joining method, with the Jukes Cantor algorithm of distance correction and bootstrapping over 1000 replicates. The scale bar indicates the number of nt substitutions per site. Black circles indicate the AstV strains detected in this study.

In all phylogenetic trees, the majority of canine AstVs formed a distinct monophyletic group. In the ORF1a-based tree (Fig. 3A), only five canine AstV strains generated in this study and two AstV strains from UK could be included, as information on the ORF1a is not available for other canine AstVs. Although monophyletic, the canine AstVs segregated in two distinct branches, with strain HUN/2012/126 in the basal position. When enlarging the number of analysed sequences, in the ORF1b (Fig. 3B), this pattern of segregation was confirmed. Four strains (HUN/2012/2, HUN/2012/6, HUN/2012/115, and HUN/2012/135) were grouped with the majority of canine AstVs identified in European and extra-European countries, whilst strain HUN/2012/126 clustered with the highly virulent strain ITA/2010/Zoid. Interestingly, strain HUN/2012/8 was distantly related to all other canine AstVs and it was grouped with AstVs identified in minks and in Californian sea lions. The unique evolutionary relationship of this canine strain was confirmed in the ORF2 (capsid)-based tree (Fig. 3C). This gene is considered as the fundamental target for classification and characterization of AstVs. When observing in detail the large monophyletic group of canine AstVs which classified into species 5 (Schultz-Cherry, 2013), it was possible to identify clearly sub-clustering patterns, with at least 6 sub-clusters. All Chinese strains, the UK strain GBR/2014/Lincoln and the Hungarian strains HUN/2012/2 and HUN/2012/135 formed a unique group, with more than 91% nt identity in the full-length ORF2. A second group included three Italian strains (ITA/2005-3, ITA/2005-6, and ITA/2005-8), the UK strain GBR/2014/Gillingham and strain HUN/2012/6, with more than 91% nt identity to each other. A third group encompassed the virulent strain ITA/2010/Zoid and strain HUN/2012/126 (97% nt identity to each other). Other canine strains (GBR/2014/Braintree, GBR/2014/Huntingdon, HUN/2012/115) were intermingled between these three main sequence groups and, as supported by sequence comparison (Table 3), they clearly appeared as distinct genetic sub-lineages.

4. Discussion

AstVs have been reported repeatedly in dogs across the world, although the association with the disease, prevalence rates and information on the genetic diversity are still largely unknown. In this study, we could neither confirm nor refute an association between AstV infection and diarrhea in dogs. Furthermore, we observed discrepancies between results obtained by the pan-astrovirus PCR assay and those derived from viral metagenomics. However, none of these methods were developed for routine diagnostic procedures and we do not have information about the actual sensitivity of these assays. At present it seems more appropriate to consider these methods, originally developed to detect viral diversity, as independent approaches that help understand the viral community and diversity in clinical/pathological specimens. Thus, our prevalence data for AstV must be interpreted with caution, even if the detection rates of AstVs fell in the ranges reported in the literature. For example, canine AstV RNA has been detected in 6–27% of dogs with enteritis and 0–19% of aysmptomatic dogs in studies in Italy (Martella et al., 2011a, Martella et al., 2011b), China (Zhu et al., 2011), Japan (Takano et al., 2015), France (Grellet et al., 2012) and UK (Caddy and Goodfellow, 2015). Even if those studies differed in the number, provenience and age of the animals enrolled in the investigations, in most studies the detection rates were found to differ significantly between symptomatic and asymptomatic dogs, suggesting a possible role of AstVs as enteric pathogens of dogs. Also, the onset and evolution of the clinical signs have been found to correlate with the patterns of virus shedding and with seroconversion in two dogs naturally infected by canine AstVs (Martella et al., 2012). Yet, experimental studies will be needed to demonstrate firmly the association of canine AstVs with gastroenteritis.

Sequencing of the ORF1a, ORF1b and ORF2 regions revealed significant sequence variation in the CAstVs detected in this study. Five strains were grouped with other canine AstVs identified worldwide, but further separated into multiple capsid (ORF2) sub-clusters. By parallelism with what is observed in human AstVs (MAstV species 1), that are classified antigenically in 8 serotypes, it is possible to speculate that the genetic heterogeneity observed in canine AstVs might account for a significant antigenic diversity (Caddy and Goodfellow, 2015). Weak antigenic cross-reactivity has been observed in immune electron microscopy between strain ITA/2008/Bari and ITA/2010/Zoid virus particles and the sera of convalescent dogs (Martella et al., 2012). However, isolation in vitro of these viruses is fastidious and only one strain, ITA/208/Bari, has been adapted to grow in vitro thus far (Martella et al., 2011a, Martella et al., 2011b), thus hampering a precise evaluation of the antigenic relationships among different canine AstVs.

Interestingly, one Hungarian strain, HUN/2012/126, resembled a highly virulent canine AstV, ITA/2010/Zoid, associated with enteric disease in an adult and young dog in Italy (Martella et al., 2012). The question whether some canine AstV strains may differ in their biological properties in terms of fitness or virulence remains open.

Even more interestingly, one of the canine AstVs identified in Hungary, HUN/2012/8, was found to be genetically distantly related from all other canine AstVs identified worldwide. Although we were successful to determine only the partial (3.2 kb) 3’end of the genome, the virus displayed unique genetic signatures, such as a longer ORF1b/ORF2 overlap (11 nt), and a longer 3′UTR. Also, this strain markedly varied from all the other canine AstVs in the highly conserved promoter region for synthesis of subgenomic RNA, located upstream of the ORF2 (Walter and Mitchell, 2003, Mendez et al., 2014). Conversely, all other canine AstVs analysed in this study displayed a conserved genomic architecture, which was shared with all currently canine AstVs for whom the complete or partial (ORF1b and ORF2) genome sequence is available (Martella et al., 2011a, Martella et al., 2011b, Martella et al., 2012, Takano et al., 2015). In addition, upon sequence comparison and phylogenetic analysis, strain HUN/2012/8 differed markedly from other canine AstVs concerning the partial ORF1b and the full-length ORF2 (Table 3). According to the 9th ICTV report (http://talk.ictvonline.org/files/ictv_official_taxonomy_updates_since_the_8th_report/m/vertebrate-official/4178), for MAstVs the mean aa genetic distances (p-dist) range from 0.378 to 0.750%, and from 0.006 to 0.312%, respectively, between and within groups (species). Using our set of ORF2 sequences, the p-dist of strain HUN/2012/8 was calculated to range between 0.350 and 0.772. Accordingly, this strain appears distantly related from any other known mammalian AstV and may represent a novel AstV species.

It remains to be established whether strain HUN/2012/8 is actually a canine virus, or it is the result of inter-species transmission from an unidentified animal source. Although AstVs are regarded as viruses with a robust host-species restriction, several pieces of evidences in mammals (including humans) indicate that the host species barrier may be permeable in some occasions, and that heterologous viruses may stably adapt to the new host (Finkbeiner et al., 2008, Finkbeiner et al., 2009, Nagai et al., 2015). Moreover, occasional transmission of AstVs is thought to have occurred between avian and mammalian species in both directions (Sun et al., 2014, Pankovics et al., 2015).

In summary, data about canine AstVs is currently scarce. Nonetheless, the genetic heterogeneity among circulating AstV strains is evident representing some challenge for laboratory diagnosis. This diversity may also be challenging for future prophylaxis strategies, complicating the design of future vaccines, as it is currently unknown whether antigenic cross-reaction exists among and cross-protection is elicited by different canine AstV strains. Further efforts are needed to better understand the biology of canine AstVs and large-scale structured surveillance programs should be initiated to elucidate the relative veterinary importance of various canine AstV types.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The study was supported by the Momentum program awarded by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. S.M. was a recipient of the János Bolyai fellowship (awarded by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences). F.J. was supported by TÁMOP (4.2.4.A/2-11-1-2012-0001) and ÚNKP-16-4-III, New Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities. G.K. received funding from ÚNKP-16-3-III, New Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

References

- Blomström A.L., Widén F., Hammer A.S., Belák S., Berg M. Detection of a novel astrovirus in brain tissue of mink suffering from shaking mink syndrome by use of viral metagenomics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:4392–4396. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01040-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch A., Guix S., Krishna N., Mendez E., Monroe S.S., Pantin-Jackwood M., Schultz-Cherry S. 2010. Nineteen New Species in the Genus Mamastrovirus in the Astroviridae Family. (ICTV 2010018aV2010b) [Google Scholar]

- Caddy S.L., Goodfellow I. Complete genome sequence of canine astrovirus with molecular and epidemiological characterisation of UK strains. Vet. Microbiol. 2015;177:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D.K.W., Poon L.L.M., Guan Y., Peiris J.S.M. Novel astroviruses in insectivorous bats. J. Virol. 2008;82:9107–9114. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00857-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Benedictis P., Schultz-Cherry S., Burnham A., Cattoli G. Astrovirus infections in humans and animals—molecular biology, genetic diversity, and interspecies transmissions. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011;11:1529–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djikeng A., Halpin R., Kuzmickas R., Depasse J., Feldblyum J., Sengamalay N., Afonso C., Zhang X., Anderson N.G., Ghedin E., Spiro D.J. Viral genome sequencing by random priming methods. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner S.R., Kirkwood C.D., Wang D. Complete genome sequence of a highly divergent astrovirus isolated from a child with acute diarrhea. Virol. J. 2008;5:117. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkbeiner S.R., Holtz L.R., Jiang Y., Rajendran P., Franz C.J., Zhao G., Kang G., Wang D. Human stool contains a previously unrecognized diversity of novel astroviruses. Virol. J. 2009;6:161. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Pan M., Wang X., Xu Y., Xie X., Knowles N., Yang H., Zhang D. Complete sequence of a duck astrovirus associated with fatal hepatitis in ducklings. J. Gen. Virol. 2009;90:1104–1108. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.008599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grellet A., De Battisti C., Feugier A., Pantile M., Marciano S., Grandjean D., Cattoli G. Prevalence and risk factors of astrovirus infection in puppies from French breeding kennels. Vet. Microbiol. 2012;157:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imada T., Yamaguchi S., Mase M., Kenji T., Masanori K., Akira M. Avian Nephritis Virus (ANV) as a new member of the family Astroviridae and construction of infectious ANV cDNA. J. Virol. 2000;74:8487–8493. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8487-8493.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käll L., Krogh A., Sonnhammer E.L.L. Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction—the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W429–W432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J.A., Healey D.S., Studdert M.J., Scott P.C., Kennett M.L., Ward B.K., Gust I.D. Viruses and virus-like particles in the faeces of dogs with and without diarrhoea. Aust. Vet. J. 1984;61:33–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1984.tb07186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martella V., Moschidou P., Buonavoglia C. Astroviruses in dogs. Vet. Clin. North. Am. Small. Anim. Pract. 2011;41:1087–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martella V., Moschidou P., Lorusso E., Mari V., Camero M., Bellacicco A., Losurdo M., Pinto P., Desario C., Bányai K., Elia G., Decaro N., Buonavoglia C. Detection and characterization of canine astroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2011;92:1880–1887. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.029025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martella V., Moschidou P., Catella C., Larocca V., Pinto P., Losurdo M., Corrente M., Lorusso E., Bànyai K., Decaro N., Lavazza A., Buonavoglia C. Enteric disease in dogs naturally infected by a novel canine astrovirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:1066–1069. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05018-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martella V., Pinto P., Tummolo F., De Grazia S., Giammanco G., Medici M.C., Ganesh B., L’Homme Y., Farkas T., Jakab F., Bányai K. Analysis of the ORF2 of human astroviruses reveals lineage diversification, recombination and rearrangement and provides the basis for a novel sub-classification system. Arch. Virol. 2014;159:3185–3196. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez E., Arias C.F. Astroviruses. In: Knipe D.M., Howley P.M., editors. Fields Virology. fifth ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 981–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez E., Muñoz-Yañez C., Sánchez-San Martín C., Aguirre-Crespo G., Baños-Lara Mdel R., Gutierrez M., Espinosa R., Acevedo Y., Arias C.F., López S. Characterization of human astrovirus cell entry. J. Virol. 2014;88:2452–2460. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02908-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalov-Kovács E., Marton S., Fehér E., Lengyel G., Jakab F., Tuboly T., Bányai K. Enteric viral infections of sheltered dogs in Hungary [in Hungarian] Magy. Allatorv. Lapja. 2014;136:661–670. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalov-Kovács E., Gellért Á., Marton S., Farkas S.L., Fehér E., Oldal M., Jakab F., Martella V., Bányai K. Candidate new rotavirus species in sheltered dogs. Hungary. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:660–663. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monceyron C., Grinde B., Jonassen T.O. Molecular characterisation of the 3’-end of the astrovirus genome. Arch. Virol. 1997;142:699–706. doi: 10.1007/s007050050112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai M., Omatsu T., Aoki H., Otomaru K., Uto T., Koizumi M., Minami-Fukuda F., Takai H., Murakami T., Masuda T., Yamasato H., Shiokawa M., Tsuchiaka S., Naoi Y., Sano K., Okazaki S., Katayama Y., Oba M., Furuya T., Shirai J., Mizutani T. Full genome analysis of bovine astrovirus from fecal samples of cattle in Japan: identification of possible interspecies transmission of bovine astrovirus. Arch. Virol. 2015;160:2491–2501. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankovics P., Boros Á., Kiss T., Delwart E., Reuter G. Detection of a mammalian-like astrovirus in bird, European roller (Coracias garrulus) Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015;34:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz-Cherry S. Springer; New York, New York: 2013. Astrovirus Research. Essential Ideas, Everyday Impacts, Future Directions. [Google Scholar]

- Sun N., Yang Y., Wang G.S., Shao X.Q., Zhang S.Q., Wang F.X., Tan B., Tian F.L., Cheng S.P., Wen Y.J. Detection and characterization of avastrovirus associated with diarrhea isolated from minks in China. Food. Environ. Virol. 2014;6:169–174. doi: 10.1007/s12560-014-9155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano T., Takashina M., Doki T., Hohdatsu T. Detection of canine astrovirus in dogs with diarrhea in Japan. Arch. Virol. 2015;160:1549–1553. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2405-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toffan A., Jonassen C.M., De Battisti C., Schiavon E., Kofstad T., Capua I., Cattoli G. Genetic characterization of a new astrovirus detected in dogs suffering from diarrhoea. Vet. Microbiol. 2009;139:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieler E., Herbst W. Electron microscopic demonstration of viruses in feces of dogs with diarrhea. Tierärztl. Prax. 1995;23:66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter J.E., Mitchell D.K. Astrovirus infection in children. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2003;16:247–253. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200306000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams F.P., Jr. Astrovirus-like, coronavirus-like, and parvovirus-like particles detected in the diarrheal stools of beagle pups. Arch. Virol. 1980;66:215–226. doi: 10.1007/BF01314735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu A.L., Zhao W., Yin H., Shan T.L., Zhu C.X., Yang X., Hua X.G., Cui L. Isolation and characterization of canine astrovirus in China. Arch. Virol. 2011;156:1671–1675. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1022-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]