Abstract

Objectives

This study examines the role and value of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in the current health care system in China.

Methods

Based on literature review and publicly available data in China.

Results

The study shows that TCM is well integrated in the Chinese health care system as one of the two mainstream medical practices. Also, the Chinese government is supportive of TCM development by increasing investment in TCM research and administration. However, there is downsizing of TCM utilization, a lack of TCM professionals with genuine TCM knowledge and skills, and limitations of and increasing public opinions on modernization and westernization.

Conclusions

TCM is still facing many challenges in playing critical roles in improving public health in China. These challenges can be explained from different perspectives. In addition to the unique characteristics of TCM, economic, cultural, and historical evolution in China may also be major determinants.

Keywords: Medicine, Chinese traditional, Delivery of health care, Complementary therapies, Health policy

1. Brief background

1.1. What is TCM

TCM is based on the Chinese philosophy of Yin–Yang and Five Elements. The oldest classic of TCM is Huangdi Neijing (Inner Canon of Huangdi or the Yellow Emperor’s Medicine Classic), which was written 2000–3000 years ago [1]. The basic theory of TCM includes five-zang organs and six-fu organs, qi (vital energy), blood, and meridians. TCM is based on the holistic principles and emphasizes harmony with the universe. It categorizes the causes of diseases into two groups: external causes and internal causes. It differentiates syndromes according to the eight principles (yin, yang, exterior, interior, cold, heat, deficiency (xu) and excess (shi)).

Although acupuncture and Chinese massage have been well known and practiced in the west, clinical diagnosis and Chinese herbology are very important components of TCM. The typical TCM diagnostic methods are inspection, auscultation/olfaction, inquiring and palpation. Chinese herbal medicine not only includes plants, but also includes medicinal uses of animals and minerals. The herbal medicine preparation (pao zhi) and formulas (fang ji) are also very critical and unique.

TCM has been carried over for thousands of years for a variety of clinical treatments of different kinds of diseases and symptoms in China. It also has experienced further development and modernization over time [2], [3]. In the 1950s, Chairman Mao Zedong authorized an attempt to create an academic/formal/systematized medicine. One of the major changes in the medicine is it eliminated everything considered to be superstitious. One example of such a concept is “Hun-Po”1 of which there was no mention in the texts of the 1960s and 1970s. In terms of acupuncture practice a certain standardization of the acupoints and needling techniques took place which was exported with the early teachers who came to the west and founded acupuncture schools on the TCM academic model. Herbal medicine and Zang Fu syndrome differentiation were also standardized. Thus, strictly speaking, the term TCM in the west should be referred as Chinese medicine rather than TCM.

1.2. Current health care system in China

During the Qing Dynasty, especially in the nineteenth century, western missionaries entered China and western medicine2 started to dominate the market. Currently, western medicine and TCM are the two mainstream medical practices in China. TCM/western integrated medicine, which attempts to combine the best practices of TCM and western medicine, and Chinese medicine of minorities, such as Mongolian medicine and Tibetan medicine, are also formally practiced in the Chinese health care system.3

The Chinese health prevention and delivery system is based on the three-tier system developed in the 1950s, which includes hospitals, health centers, and clinics. Table 1 shows the number of health institutions in 2006. In general, hospitals have the best facilities and resources while health clinics/health service centers provide most of the health services, especially for treating patients with common illnesses and non-severe health conditions. Currently, 99% of the health centers are in the rural areas and they are also very important for rural health delivery.

Table 1.

Number of health institutions and clinics in China 2006.

| Institutions | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital | 19246 | 2.12% |

| General Hospital | 13120 | 1.44% |

| TCM Hospital | 2665 | 0.29% |

| TCM-WM Hospital | 211 | 0.02% |

| Minority Hospital | 196 | 0.02% |

| Specialized Hospital | 3022 | 0.33% |

| Nursing Hospital | 32 | 0.00% |

| Health Center | 40791 | 4.49% |

| Township Health Center | 39975 | 4.40% |

| Urban Health Center | 816 | 0.09% |

| Village Clinic | 609128 | 67.02% |

| Non-village Clinic | 205814 | 22.64% |

| Community Health Service Center | 22656 | 2.49% |

| Outpatient Department | 6429 | 0.71% |

| MCH Center | 3003 | 0.33% |

| Sanatorium | 264 | 0.03% |

| Specialized Disease Prevention & Treatment Institute | 1402 | 0.15% |

| First-aid Station | 160 | 0.02% |

| Center of Clinic Examination | 35 | 0.00% |

| Total | 908928 | 100.00% |

Source: China Health Statistics Year Book 2007, available at http://www.moh.gov.cn/open/2007tjts/P88.htm, http://www.moh.gov.cn/open/2007tjts/P109.htm, accessed in April.

Before the economic reform in 1978, the central government was responsible for both health care financing and delivery. Since 1978, a series of health care reforms were conducted to decentralize and privatize health care organizations. Although most of the hospitals are still state-owned, many private clinics have opened in both urban and rural China. The government also dramatically reduced their financial investment in health care services, but still has tight price-control in the health sector [4].

The current Chinese health care system is undergoing major reforms in order to increase health insurance coverage, improve quality of care, reduce health care costs, and minimize inequality of health care access between rural and urban areas. In the following, the paper describes the situation and changes of TCM in the health care system in the past decade. It also discusses the challenges and opportunities facing TCM in China.

2. Chinese herbal medicine industry

Chinese herbal medicine is currently categorized into three groups in China: raw herbal medicine (zhong yao cai), sliced herbal medicine (zhong yao yin pian),4 and patent medicine (zhong cheng yao).5 In addition to 561 herbal resource centers in China that produce raw herbal medicine, there are over 1500 manufacturers producing sliced herbal medicine and 684 manufacturers producing patent medicine [5]. Although herbal extracts are regarded as herbal medicine, strictly speaking, they are not Chinese herbal medicine since they are not based on Chinese herbology, but active ingredients or compounds extracted from herbs. They are listed as biomedicine in China.

In addition to the Drug Administration Law of the People’s Republic of China, Chinese herbal medicine production, distribution, pricing, and utilization are under the regulations of different government agencies, such as the Chinese State Food and Drug Administration and the National Development and Reform Commission. Although the Chinese government has implemented quality control systems on medical production, such as implementations of the Good Agricultural Practice (GAP), the Good Laboratory Practice (GLP), and the Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) for many years, there is still need to improve the quality control in the production of herbal medicine. Due to the complexity of Chinese herbal medicine, the critical component combinations and the appropriate standard component combinations are not quite clear. For example, since there is neither strict standards for controlling critical components in the patent medicine nor regulations on the process for sliced herbal medicine, some manufacturers are either using less effective components or cheap substitutes [6].

TCM products have been exported to about 163 countries in the world. Based on the report from the China Chamber of Commerce for Import & Export of Medicines & Health Products (CCCMHPIE), the TCM herbal medicine export is almost US$ 1.2 billion in 2007, which increased 8% from 2006. Depending on different definitions and calculation, Chinese herbal medicine represents 20–50% of the herbal medicine market share worldwide.

3. TCM health professionals

3.1. Education

Historically, TCM knowledge and skills were passed on only to family members or a couple of students through apprentice-master relationships. Since the 1950s, TCM education has been formalized into an academic training. Typically, TCM medical professionals are educated at medical schools or pharmacy schools with the same standards, admissions, and years of training as western medical professionals. Students usually take 3–8 years’ of training to get associates, bachelors, masters, or doctoral degrees from either TCM or other universities (Table 2 ). Among the 400,000 enrolled students, there are almost 4000 foreign students enrolled. 90% of them are from Asia, followed by 4% from North America and 4% from Europe.

Table 2.

TCM education statistics in China 2006.

| Institution Category | Number of Institutions | Students Graduated | Students Recruited | Students Enrolled |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCM University | 44 | 65278 | 100,747 | 331,510 |

| Western Medical University | 75 | 9188 | 18,311 | 58,424 |

| Non-medical University | 126 | 6575 | 11,808 | 35,912 |

Note: The number of students includes all TCM students for associates, bachelors, masters and Ph.D. degrees.

Source: China Statistical Year Book of Chinese Medicine, available at http://www.satcm.gov.cn, Tables c01, c04 & c05, accessed in March 2008.

In addition to TCM theories and methodology, the fundamental TCM curriculum includes western medical science such as physiology and molecular biology. In 1959, TCM curriculum requires the course time ratio to be no less than 7:3 between TCM and western medicine. The current TCM training is much more westernized with the ratio of 6:4 or even 5:5, which causes concerns from TCM experts about the quality and time limitations in providing sufficient TCM knowledge and training [7].

3.2. Clinical regulation

TCM is also under the same registration and licensing procedures as is western medicine. In 1999, the Chinese government implemented medical professional licensing requirements. After receiving regular degree training, both doctors and pharmacists6 are required to do 1 to 3 years of residency in a medical institution before taking a national license examination to get their licenses [8].

Since TCM is a practical study, which emphasizes the clinical experience as well as family lineage, those TCM practitioners who have studied traditional medicine under a teacher for at least three years or have really acquired specialized knowledge of medicine through many years’ experience are also allowed to participate in the examination for the qualifications of medical practitioners. However, the complex process and certain requirements of the exam (e.g. some specific western medical science knowledge) prevent some TCM practitioners from getting their licenses.

3.3. Clinical practice

TCM professionals dramatically decreased from 800 thousand in 1911 to 500 thousand in 1949 due to the growing popularity of western medicine [9]. The number of TCM professionals also dropped further after the Chinese government implemented medical professional licensing requirements in 1999.

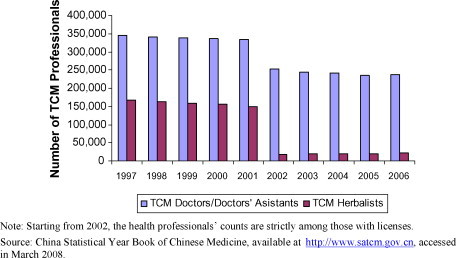

Fig. 1 shows the trend of the number of TCM doctors and herbalists from 1997 to 2006. Starting from 2002, the health professionals’ counts are strictly among those with licenses. In 2006, 166,614 TCM doctors, 21,324 TCM pharmacists, and 28,514 TCM doctors’ assistants were practicing in hospitals; there were 33,574 TCM doctors and 7843 TCM doctors’ assistants practiced in health clinics and community health service centers.

Fig. 1.

Trend of TCM professionals in China 1997–2006.

In health clinics, doctors who practice western medicine comprise 50.3% of the total doctors, followed by 32.3% of doctors who practice TCM/western integrated medicine, and 17.4% who only practice TCM [10]. Currently, about 12% of the licensed doctors are TCM doctors and only 6% of pharmacists are licensed TCM herbalists. Very few licensed TCM doctors or pharmacists work in township health centers or village clinics.

4. Clinical outcomes and research

TCM has been used for thousands of years in treating different types of diseases and symptoms, such as pulmonary, cardiovascular, gynecological, and pediatric, as well as mental illness [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. During the epidemic of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003, the SARS death rate in China (6.5%) is less than the average international death rate (9.5%) [19]. Among the 5326 SARS patients treated, 3104 cases involved TCM treatment. This represents 58.3% of the total. Specifically, in Guangzhou, where the integration of TCM started the earliest, the death rate was only 4%. In Beijing, the death rate decreased 80% after integrating TCM treatments. Recently, the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of the People’s Republic of China, the Chinese Ministry of Health, and the Treasury Department are collaborating on a program to provide free TCM treatment for 4500 HIV/AIDS patients in 11 provinces. The preliminary clinical results based on 2300 patients in 2004 are encouraging.

However, along with other countries worldwide, the safety and efficacy issues of TCM are still major challenges in China. For example, TCM is more often used for chronic conditions than acute conditions. It is more complicated to evaluate its clinical effects. For example, some Chinese herbal medicine is prescribed to treat diseases from the root cause rather than to decrease the symptoms immediately. So, it might take months or years for patients to recover, which is problematic for most of the clinical designs in order to evaluate long-term outcomes.

Currently, there are about 800,000 references and abstracts to literature on TCM in the Traditional Chinese Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System (TCMLARS). However, very few of them are regarded as “rigorous” scientific evidence of efficacy and safety of TCM treatment based on western medical methodology, such as randomized clinical trials (RCT). Although both Chinese and Western experts realize that RCT may not be appropriate to evaluate TCM since it requires individualized treatment based on the diagnosis of each patient, there is not any innovative evaluation design available [20]. To fill the gap between TCM and evidence based medicine (EBM), efforts have been put on conducting systematic reviews and clinical studies in China [21]. For example, as part of the international Cochrane Collaboration, the Chinese EBM/Cochrane Center was established in China in 1999. It provides both clinical control trial studies and meta-analysis reviews on the available studies of TCM.

Many government agencies are also involved and increasing their investment on TCM research. These agencies include the Chinese Ministry of Health (MOH), the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of the People’s Republic of China (SATCM), the State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA), and the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (MOST). TCM research institutes received over 300 million RMB for their research and development in 2005, which increased from 80 million RMB in 1999. Many research efforts have been spent on integrating TCM with western medical treatment and developing information processing techniques for intelligent diagnosis of TCM [22].

5. TCM utilization

In addition to TCM diagnosis, such as pulse diagnosis and tongue diagnosis, the common TCM treatments include herbal medicine, acupuncture/moxibustion, cupping, gua sha,7 and Chinese massage (tuina, an muo and qian yin). The total number of TCM out-patient visits is almost 1.3 billion per year, which is about one third of the total out-patient visits in China [10]. Almost 40% of these TCM visits are delivered in village clinics/community health service centers, followed by 28% in TCM hospitals, 16% from health centers, 10% in other hospitals, and 7% from private clinics and others.

5.1. In hospitals

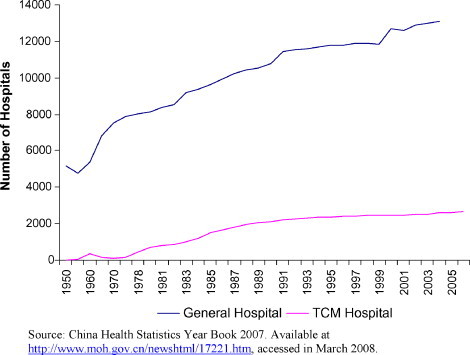

Table 1 shows that TCM hospitals represent 13.8% of all hospitals in China and TCM/western medicine integrated hospitals only represent 1.1%. In addition to the small proportion, the relative growth rate of TCM hospitals is much slower than general hospitals (Fig. 2 ). TCM hospital out-patient visits are only about 18% of the general hospital visits.

Fig. 2.

Comparisons of TCM and western hospitals.

The ratio of TCM hospitals to other hospitals and their visits does not provide us the whole picture of TCM practices in hospitals since TCM and western medical practices are mixed in both types of hospitals. First, about 90% of the general hospitals have TCM departments although the TCM department outpatient visits only represent 8% of the total outpatient visits in general hospitals [10]. Second, in TCM/western integrated hospitals, TCM related treatment is about 40–45% of the total treatments given.

Third, almost all of the TCM hospitals are practicing western medicine as well as TCM [19]. In addition to using stethoscope and biomedical diagnostic tests, western surgeries for different kinds of diseases (e.g. liver, stomach, kidney, and breast cancer) are also common practice in TCM hospitals. As discussed earlier, the challenges of TCM clinical effectiveness may explain in some part the use of western medicine in the TCM hospitals. Furthermore, due to the health reforms in the 1990s, most of the hospitals in China have to take care of themselves financially with less and less government investment [4]. In general, TCM practice is much cheaper and has a lower profit margin than western medicine. Many TCM hospitals depend on government subsidies for survival [23]. It was reported that almost three quarters of the TCM prices are lower than their actual costs [24]. Thus, most of the TCM hospitals implement western technology in diagnosis and treatment.

Since the government regulates and controls most of the utilization prices in hospitals, most of the hospital profits are from prescription drugs. This causes further overuse of western medication in many TCM hospitals as well as general hospitals. It was reported that 37% of outpatient medication revenue in TCM hospitals were from western medicine, followed by 35% from patent medicine and 28% from raw/sliced herbal medicine [25]. Western medication utilization is even higher among in-patients in TCM hospitals. Western medication revenue comprises almost 78% of the total medication revenue and 37.4% of the total revenue in TCM hospitals. Chinese herbal medicine only represents 22% of the medication revenue and 8.1% of the total revenue in TCM hospitals.

5.2. In other health centers and clinics

Similar to hospitals, both TCM and western medicine are practiced alongside each other in health centers and health clinics. About 75% of health centers have a TCM department. Including TCM/western integrated medicine treatment, the total TCM out-patient visits were 330 million, which was much higher than those visits in all TCM hospitals in 2001 [10].

In health centers, Chinese herbal medicine revenue represented less than 15% of the total medication revenue. However, about one third of the total medical utilization in health clinics was from TCM, which was more than the TCM utilizations in TCM hospitals and health centers.

5.3. Public opinion

Although a majority of Chinese believe in TCM, only a small portion of them prefer TCM treatment to western medical treatment when they are sick. In a survey conducted among 1161 out-patients, 19% of the respondents said they have never had any TCM treatment. 25% of the respondents said they have TCM treatment because they have chronic conditions while another 17% said they have TCM treatment because western medicine failed to cure them [26].

Another larger household survey of 42,819 people in both urban and rural China also showed that 54% of the population prefers western medical treatment, 25% prefers TCM/western integrated treatment, 12% prefers TCM treatment only, 5% western medicine for acute conditions while TCM for chronic conditions, and 1% prefers western medicine for diagnosis while TCM for treatment [10]. For those people who prefer TCM treatment, the main reason to choose TCM is their belief in TCM (50.7%), followed by its good clinical outcome (21.5%), its treatment of the cause (11.2%), frequent adverse-reaction of western medicine (8.7%), and inexpensive price (6.8%).

In general, age is positively related to people’s choice of TCM treatment although after 65 the trend reverses. People with less than a grade school level of education and those with higher than college are more likely to use TCM. Females, people who live in urban areas, and people with professional occupations are also more likely to use TCM.

6. Discussion and conclusions

TCM is well integrated in the Chinese health care system. However, TCM is still facing many challenges in playing critical roles in improving public health in China. These challenges can be explained from different perspectives. In addition to the unique characteristics of TCM, economic, cultural, and historical evolution in China may also be the major determinants.

First, although the TCM philosophy is an important part of the Chinese culture, TCM theories and methodologies are still not confirmed or measurable by modern science. For example, the mechanism of the different functions of the five-zang and six-fu organs is not clear. It is still hard to measure different kinds of qi, such as vital qi and wei qi. TCM diagnosis tools are less tangible and its clinical outcomes are less documented than western medicine. In addition, Chinese herbal medicines are neither as easy to take nor as fast to reduce symptoms as western medications. These factors are important in explaining why western medicine is used more than TCM in China.

Second, due to the success of economic reform in the past 30 years, the concept of westernization and modernization are popular among the Chinese people. Some medical professionals and consumers regard TCM as far behind or less developed than western medicine [27]. Although some Chinese, especially those with a high level of education understand the side-effects and medical error problems of western medical treatment, very few studies or statistics are available on the issues in China. So, the knowledge and concerns about the adverse-effects of western medicine are much less than those in the US or in Europe.

Currently, there are many highly regarded TCM programs and practitioners in China, such as Beijing TCM University and Shanghai TCM University. However, due to the difficulty in evaluation and regulation of TCM throughout history and adulterants of Chinese herbal medicine and quack TCM doctors some negative opinions of herbal medicine and TCM professionals still exist. In rural China, the situation is worse since there is lack of health facilities and professionals. Specifically, very few licensed TCM professionals are available there. These may not only explain why western medical treatment is more used than TCM in rural China, but also indicate the complex environment for public health services.

Third, due to the historical evolution and cultural changes, some of the traditional knowledge is lost in both the formal TCM practice and the education system. As discussed earlier, the lack of the genuine knowledge also causes problems in Chinese herbal medicine production and regulation, which results in a negative impact on TCM clinical outcomes.

Experts argue that if Chinese herbal medicine is prepared, prescribed, and used properly based on the TCM principles and Chinese herbology (e.g. the principle of jun, chen, zuo, shi), they are very safe. Most of the severe adverse-effects and toxicity occurred not due to high risks of Chinese herbal medicine, but due to misuse or lack of genuine TCM knowledge [28], [29], [30]. Similar to herbal extracts and intravenous (IV) formulae of herbal products, some of the new Chinese patent medicines are not fully developed based on the TCM principles and Chinese herbology [3]. Although they are approved by the Chinese State Food and Drug Administration, the clinical outcomes of these products are not as remarkable as these traditional formulae.

Fourth, the limitations of hospital finance may also push the movement of western medicine in China. As discussed earlier, since Chinese hospitals are expected to generate revenue to cover the majority of their expenses, they have incentives to use western medical devices and treatment due to the lower profit margin of TCM. The low profitability of TCM makes the TCM labor market less attractive. Students also have less incentive to carry on the genuine TCM practice and TCM professionals have more incentive to practice western medicine.

Finally, there are also concerns on the integrated practice of TCM and western medicine since they are based on different philosophies and theories. As previously discussed, the integrated practices are found not only in those TCM/Western medicine hospitals, but in all other type of medical institutions and with different forms. In addition to integrated treatment, some patients use western medicine for diagnosis and use TCM for treatment. Some others use TCM for chronic conditions and use western medicine for acute conditions. Although some studies have shown that integrated practice has the potential to improve clinical results [31], there are also concerns that the traditional TCM characteristics are more likely to be ignored in the integrated practice. A study showed that only 30,000 TCM doctors in China are still prescribing raw/sliced herbal medicine based on TCM theory and Chinese herbology [9]. The majority of TCM doctors only prescribe western medications.

In response to these challenges, the Chinese government is putting a lot of effort in protecting and expanding the roles of TCM in the health care system in the past decade. In addition to increasing investment in clinical research and regulation as discussed earlier, different government agencies are collaborating to develop a series of initiatives to promote TCM, such as studying the basic theory of TCM, identifying and supporting senior TCM experts to pass along the ancient knowledge, and training a group of TCM elites to inherit the experience [32]. The Chinese government is also looking for ways to fit the traditional TCM care framework into the current health care system. For example, a trial study on permitting TCM doctors to treat and prescribe herbal medicine to patients in herbal medicine shops will be conducted in nine cities/counties in China from July 2007 to March 2008 [33].

Since the Chinese health care system is very centralized, the government’s role is very critical for the future of TCM. With the on-going major health care system reforms to provide accessible, affordable, and equal health care, the Chinese government should consider how to provide sufficient investment on TCM and allocate the limited resources rationally. Specifically, government needs to build up its own infrastructure and provide regulations and public polices on TCM to facilitate consumers and health services providers.

After developing a reasonable, simple, transparent and consistent TCM regulation system, more focus should be on how to effectively implement and enforce those regulations and initiatives. Complete investigations should be conducted to evaluate whether these regulations and initiatives are cost effective from society’s perspective.

In addition to educating the public on TCM, the government should also educate the public on the risks of western medicine. In addition to investigating and releasing information on adverse-reaction and medical errors, the government can also provide knowledge and studies on the current development of Traditional Medicine and Alternative and Complementary Medicine in western health systems. This knowledge will encourage the Chinese people to open their minds and reconsider the value of TCM in the Chinese health care system.

Under the current economic situation in China, further studies should also investigate the competitiveness of the TCM market and the behavior of consumers and health providers. It is critical to develop well-designed survey studies in order to further investigate the determinants of the TCM utilizations. For example, what is the impact of health insurance and other socio-economic factors? Do historical factors, such as the adverse campaign on TCM during the Cultural Revolution result in some cohort differences in the TCM utilization? For example, what is the funding impact from pharmaceutical companies and medical device companies on western medicine usage and TCM medicine? Do the pharmaceutical companies and herbal medicine manufacturers have different profitability, marketing strategies, social and political impact on health care policies and regulations, which directly or indirectly influence western medicine and TCM practices? Better understanding of the pattern of TCM utilization can help government reform the health delivery and financing infrastructure. It can also guide government to provide specific policies, such as promoting TCM in specific geographic locations, for subgroups who may receive more benefit from TCM treatment, and to efficiently allocate TCM resources.

Acknowledgement

We would like to give our thanks to Mr. Brian McKenna for his comments.

Footnotes

Based on Huangdi Neijing, Hun, Po, Yi, Zhi, and Shen are housed in the five-zang organs.

In this paper, western medicine (xi yi) specifically refers to biomedicine/allopathic medicine since other types of practice, such as osteopathy and naturopathy are not practiced formally in China. We use the general term of western medicine just to distinguish it from Chinese Medicine (zhong yi).

In this paper, we use TCM as the term to separate it from western medicine and other types of modern developed Chinese medicine. Chinese medicine sometimes is interchangeable with TCM in the current literature.

Sliced herbal medicine is the herbal medicine that has been processed. In addition to basic processes such as slicing, steaming, and drying, some raw herbal medicine is processed with ginger, honey, licorice, and sulfur. The major purpose of these processes is to reduce toxicity as well as to sanitize.

Patent medicine is the herbal medicine formula that has been standardized rather than been “patented”.

In China, herbalists are called Chinese Medicine pharmacists (zhong yao shi).

Gua Sha is a TCM technique to remove blood stagnation by firmly rubbing a person’s skin with a special instrument.

References

- 1.Unschuld P.U. University of California Press; Berkeley/Los Angeles, CA: 2003. Huang Di Nei Jing Su Wen: Nature, Knowledge, Imagery in an Ancient Chinese Medical Text. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia Q. Traditional Chinese Medicine Could Make ‘Health for One’ True. World Health Organization; 2005. Document no. 18. http://www.who.int/intellectualproperty/studies/Jia.pdf.

- 3.Poter R. Chinese medicine. In: Poter R., editor. The greatest benefit to mankind: a medical history of humanity. Harper Collins Publishers Ltd; 1998. pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenthal D., Hsiao W. Privatization and its discontents—the evolving Chinese health care system. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:1165–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr051133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang H.L., Guo F. Past, present, and future of TCM. Henan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 1997;12(2):5–8. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang C.L., Wang R.F. The problems and suggestions on traditional Chinese Patent medicine processing. Research and Information on TCM. 2003;5(8):17–18. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao X.R. A couple of thoughts on how to train students with TCM thinking skills. Education of Chinese Medicine (ECM) 2004;23(6):76–77. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Z.B., Yang J.S. Comparative Analysis of Jinxian dai licensing procedure and rules for TCM doctors. Education of Chinese Medicine (ECM) 2004;23(6):55–59. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia Q. The curative effect and prospect of TCM against AIDS. China Soft Science. 2005;(05):21–24. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SATCM Committee . Hei Long Jiang Scientific and Technology Publisher; 2003. Demand and utilization of TCM services in China. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y.Q., Huang H.Y., Yang P.L. Development of TCM on COPD. New TCM (xin zhongyi) 2007;39(1):99–101. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin L.P., Si X.C. Current situations of TCM treatment on coronary heart disease and angina. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Chinese Materia Medica of Jilin. 2005;25(1):56–58. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y.Q. Review of TCM research on epilepsy. Journal of Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2007;9(1):164–165. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang K.Q. Review of TCM treatment on Chronic Hepatitis B. International Journal of TCM. 2007;29(1):35–39. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang C.Y., Zhang S.J. Effect of Chinese herbs in treating hepatic fibrosis induced by chronic hepatitis B. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation. 2006;15:151–153. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng H.M., Meng M.R. TCM treatment on Refractory Nephrotic Syndrome (RNS) Heilongjiang Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2007;02:56–58. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y.S. The study about diagnosis and treatment of child attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder in Chinese traditional medicine. Medical Recapitulate. 2006;12(14):895. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y.J., Xu H.X. Research progress on anti-diabetic Chinese medicines. New TCM. 2006;29(6):621–625. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y.J., Jia Q. Current TCM development and administration reform. Medicine World. 2004;5:14–23. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. Institute of Medicine. The National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed]

- 21.Liu W., Liu B., Xie Y. Study on application of evidence based medicine in internationalization of traditional Chinese medicine. World Science and Technology/Modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Materia Medica. 2006;8(3):42–46. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou C.L., Zhang Z.F. Progress and prospects of research on information processing techniques for intelligent diagnosis of traditional Chinese medicine. Journal of Chinese Integrative Medicine. 2006;4(6):560–566. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hesketh T., Zhu W.X. Health in China: Traditional Chinese medicine: one country, two systems. BMJ. 1997;315:115–117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7100.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Major roles of western medicine in TCM hospitals. Finance and Economics Daily; February 2007 [in Chinese].

- 25.Liu YL. Decreasing TCM clinical utilization. Health Newspaper; December 2006 [in Chinese].

- 26.Huang L., Chen J.Y., Zhu M., Wu S.P. A study of TCM treatment choices among outpatients. Jiangsu Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2007;39(4):51–53. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke A., Wong Y.Y. Traditional medicine in china today: implications for indigenous health systems in a modern world. American Journal of Public Health. 2003 July;93(7):1082–1084. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma Y.Q. TCM herbal drug toxicity analysis and prevention methods. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs. 2005;7:153–155. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu T.Y., Du B.X. Analysis of 169 cases of adverse reactions induced by puerarin injection. Practical Pharmacy and Clinical Remedies. 2007;10(4):230–231. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng C.Y., Mei Q.X. Causes for adverse reactions of traditional Chinese medicine injections: a case study of the “Houttuynia Cordata Injection Event”. China Pharmacy. 2007;18(6):401–403. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y., Guo J.J., Healy D.P., Zhan S. Effect of integrated traditional Chinese medicine and western medicine on the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome: a meta-analysis. Pharmacy Practice. 2007;5(1):1–9. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552007000100001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Outlines on TCM innovation and development 2006–2020. http://www.most.gov.cn/tztg/200703/t20070320_42240.htm, accessed on 08/18/08.

- 33.Temporary Regulation on TCM doctors’ practice in herbal medicine shops. http://www.satcm.gov.cn/zwxx/flfg/gfxwj/20071217/145911.html, accessed on 08/18/08.