Abstract

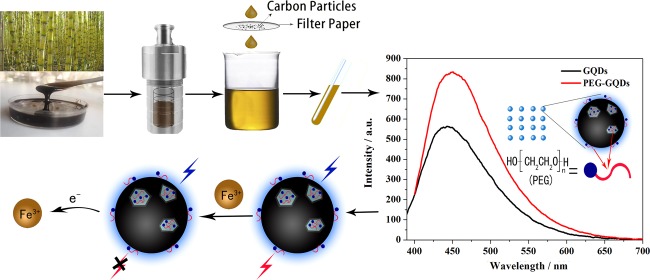

Poly(ethylene glycol) passivated graphene quantum dots (PEG-GQDs) were synthesized based on a green and effective strategy of the hydrothermal treatment of cane molasses. The prepared PEG-GQDs, with an average size of 2.5 nm, exhibit a brighter blue fluorescence and a higher quantum yield (QY) (up to approximately 21.32%) than the QY of GQDs without surface passivation (QY = 10.44%). The PEG-GQDs can be used to detect and quantify paramagnetic transition-metal ions including Fe3+, Cu2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, and Mn2+. In the case of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution as a masking agent, Fe3+ ions can be well selectively determined in a transition-metal ion mixture, following the lowest limit of detection (LOD) of 5.77 μM. The quenching mechanism of Fe3+ on PEG-GQDs belongs to dynamic quenching. Furthermore, Fe3+ in human serum can be successfully detected by the PEG-GQDs, indicating that the green prepared PEG-GQDs can be applied as a promising candidate for the selective detection of Fe3+ in clinics.

Introduction

GQDs are well known as a distinguished candidate for metal-ion analysis due to its small size, good biocompatibility, and easy chemical modification of the surface, which implies a good potential application in the fields of environmental detection, biological imaging, drug carrier, and photocatalytic and electrocatalytic technology.1−5

Toxicity presents a common practical problem in traditional QDs containing CdS, CdSe, CdTe, and PbS that limit their application in biomedicine.6−8 Therefore, it is necessary to choose a green and nontoxic material as a carbon resource to prepare GQDs. Some biomass materials such as durian,9 rice husks,10 etc. are chosen as carbon resources owing to their low price, easy access, and eco-friendliness.

GQDs can be prepared by top-down and bottom-up approaches. The “top-down” synthesis involves stripping large carbon sources into very small quantum dots by physical or chemical means. The “bottom-up” synthesis, as opposed to the top-down synthesis, uses very small carbon materials such as molecular or ionic states to produce quantum dots.11,12 The characteristics of luminescent color adjustment, dimensional dependence, pH dependence, excitation wavelength dependence, and solvent dependence associated with these preparation methods have been reported.13 Although the research on GQDs has made tremendous progress, many problems need to be solved. The design of high-fluorescence quantum yield (QY) GQDs and the improvement of physicochemical properties of GQDs remain a challenging research task, which severely limits its practical application. To enhance the performance of GQDs, surface treatment is present to revise the GQDs surface with chemicals with functional groups. Surface treatment with various molecules has been developed as a facile and cost-effective approach to manipulate the properties of GQDs in recent years.14,15 Sun et al.16 reported that the QY of GQDs modified with amino groups is six times higher than that of unmodified GQDs. The results show that only a few defect-free GQDs generate band gap fluorescence in the limited size sp2 region, and most GQDs inevitably introduce surface defects in the preparation process. These defects on the surface will form many level traps or surface state energy levels, which will become nonradiative recombination centers of electron and hole, leading to a decrease in luminous efficiency. The surface of quantum dots was usually modified to eliminate the defect state luminescence caused by surface defects and improve luminous efficiency.

Ferric ion (Fe3+), as the main form of iron elements, can be combined with a variety of proteins. However, Fe3+ is detrimental when present in excess in vivo, causing a variety of diseases. Hence, the monitoring of Fe3+ is of great significance in life. So far, a variety of methods have been introduced and developed for the detection of Fe3+, involving REDOX titration, gravimetric method, and spectrophotometric method. However, the shortcomings of these methods, such as long test cycle, multiple analysis steps, wastage of reagents, and interference of impurities in the determination results, limit their usage. Therefore, effective improvement in terms of detection technology is essential.

In this paper, we report our work on the preparation of GQDs using cane molasses, an environment-friendly as well as economically inexpensive natural waste biomass, as carbon source, and surface modification of PEG (PEG-GQDs) was carried out by a facile and rapid method. The modified GQDs show stronger fluorescence, higher QY, and better stability than the unmodified synthetic GQDs. Moreover, the fluorescence quenching and the selectivity of PEG-GQDs for the detection of Fe3+ were also investigated.

Results and Discussion

Morphology and Composition of the PEG-GQDs

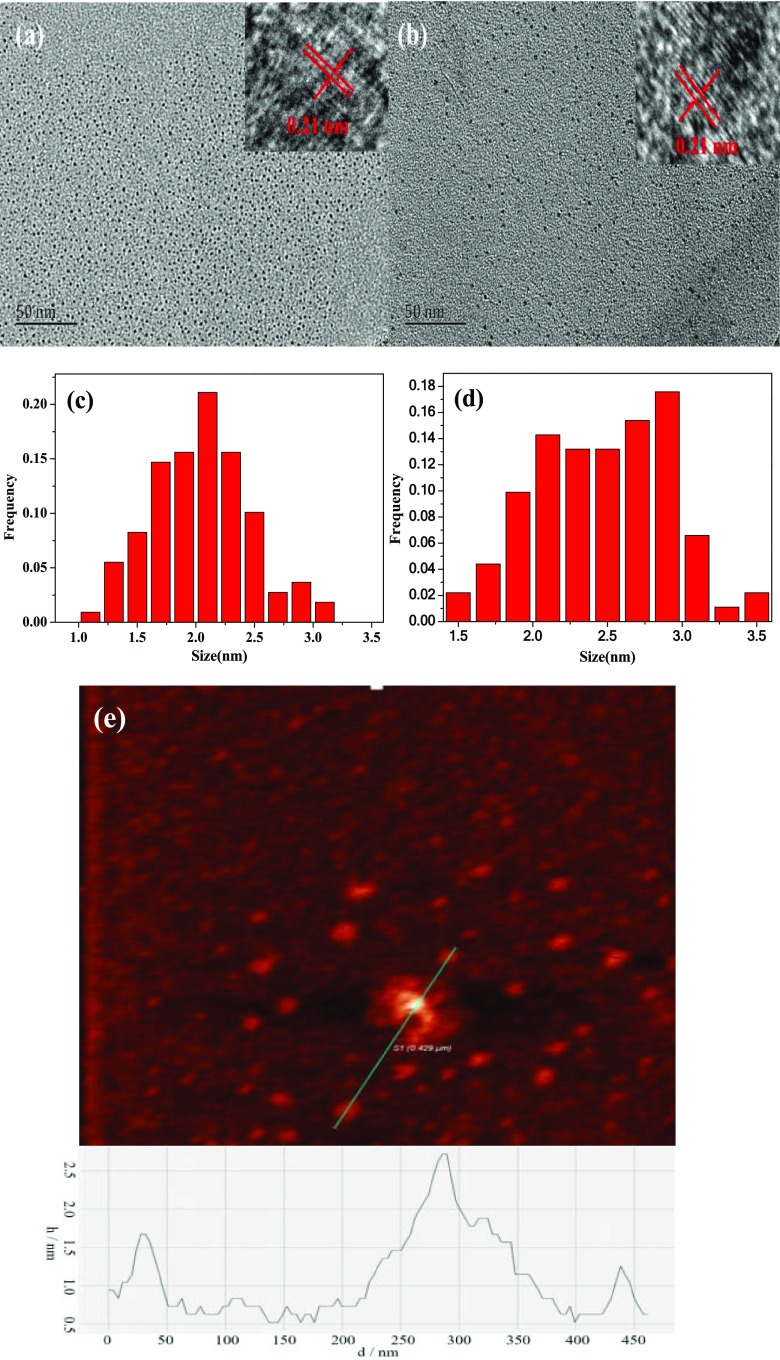

Different conditions were tested for the best performance of GQDs, and it was found that a volume ratio of 1:16 (Vcane molasses/Vultrapure water), reaction temperature of 190 °C, and the reaction time of 24 h yielded the best result, so this condition was used throughout the present work (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the synthesized GQDs and PEG-GQDs in Figure 1 demonstrate that both GQDs and PEG-GQDs are present with nearly spherical morphology. The average particle size of PEG-GQDs (Figure 1b) appears to be similar to that of GQDs (Figure 1a), but the dispersion of PEG-GQDs is better than that of GQDs. The GQDs exhibit an average diameter of 2.2 nm when counting about 100 particles ranging from 1.1 to 3.2 nm (Figure 1c). For PEG-GQDs, the particle size was found to range from 1.5 to 3.5 nm with an average lateral size of about 2.5 nm (Figure 1d). High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images show that the graphitic lattice of both GQDs (the inset of Figure 1a) and PEG-GQDs (the inset of Figure 1b) possesses a lattice spacing of 0.21 nm, which are assigned to the (100) of graphitic carbon, suggesting a highly uniform crystallinity of the produced GQDs and PEG-GQDs.17

Figure 1.

TEM and HRTEM images of (a) GQDs and (b) PEG-GQDs; size distribution of (c) GQDs and (d) PEG-GQDs; and (e) atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of GQDs.

The AFM image in Figure 1e displays that the maximum thickness of the GQDs is no more than 2.7 nm, corresponding to three to eight layers of graphene.

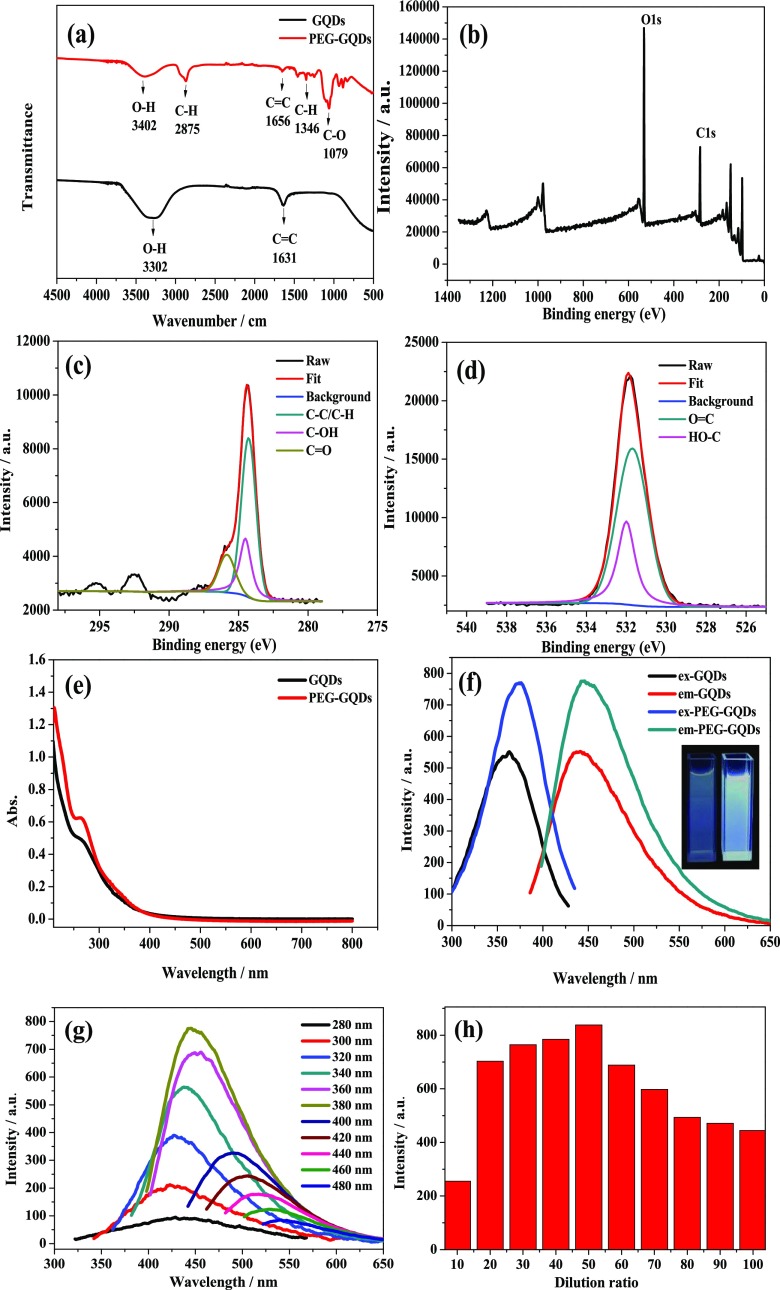

Figure 2a displays the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of GQDs and PEG-GQDs, with assignments of functional groups of the GQDs and PEG-GQDs labeled. The broad band in 3402 and 3302 cm–1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of O–H. The weak peaks at 1631 and 1656 cm–1 are related to C=C skeletal vibrations.18,19 Compared to the GQDs FTIR spectrum, three additional peaks at 2875, 1346, and 1079 cm–1 emerge in PEG-GQDs in the FTIR spectrum, which is due to the stretching vibration, bending vibration of C–H, and the stretching vibration of C–O, respectively.20,21 These results verified that hydroxyl, carbon–hydrogen bond, and carbon–oxygen were present in the PEG-GQDs sample.

Figure 2.

(a) FT-IR spectra of GQDs and PEG-GQDs. (b) X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) survey scan spectrum of PEG-GQDs. High-resolution XP spectra of (c) carbon and (d) oxygen of PEG-GQDs. (e) UV–vis absorption spectra of GQDs and PEG-GQDs. (f) Fluorescence emission spectra of GQDs and PEG-GQDs and the inset of the fluorescence photographs of GQDs (left) and PEG-GQDs (right). (g) Fluorescence emission spectra of PEG-GQDs recorded for progressively longer excitation wavelengths from 280 to 480 nm. (h) Diameter histogram of the effect of adding an amount of PEG on the fluorescence emission spectra of PEG-GQDs.

The XPS survey scan spectrum of the PEG-GQDs is shown in Figure 2b, which displays two binding energy peaks at 285 and 532 eV, corresponding to C 1s and O 1s, respectively. The C 1s spectrum shown in Figure 2c can be deconvoluted into three components at 284.2, 285.3, and 286.6 eV, which are attributed to the C–C/C–H, C–OH, and C=O, respectively.22 The O 1s spectrum (Figure 2d) shows two major components at 531.5 and 532.2 eV, which are related to the O=C and HO–C groups, respectively.20 These functionalities of PED-GQDs are consistent with the infrared spectroscopic analysis results, indicating that PEG was coated effectively on the surface of GQDs.

Optical Properties and Stability of PEG-GQDs

UV–vis absorption and fluorescence spectra of the PEG-GQDs were also collected at room temperature to study the effect of surface modification of PEG on optical properties, and the results are shown in Figure 2e. Both GQDs and PEG-GQDs have an absorption peak near 260 nm, which is assigned to the π–π * transition of the C=C bond.21,23 In contrast, the absorption peak at 260 nm of the PEG-GQDs has a more obvious variation tendency, which may be due to the fact that the polarity of water is stronger than that of PEG, since the strong polar solvent may entail the spectrum fine structure from the vibration effect to disappear and produce a wide peak.24

The excitation and emission fluorescence spectra of the GQDs and PEG-GQDs are displayed in Figure 2f. A fluorescence emission peak was observed at 440 nm for GQDs, and a fluorescence emission peak was observed at 445 nm when PEG-GQDs were excited at 376 nm. The emission peak position of PEG-GQDs appeared to shift to red compared to the GQDs emission peak, which suggests that the electronic state of the GQDs was affected by the coating of PEG. The electrons on the GQDs layer can easily jump to the PEG layer. However, the holes that should have been paired with these electrons can only stay on the surface of the GQDs, resulting in a relatively small separation of electrons from the holes. This small separation reduces the binding energy of excitons formed, leading to the red shift of PEG-GQDs peak position.25

The relationship between the fluorescence emission peak position of GQDs and PEG-GQDs and the excitation wavelength was investigated by exciting at different excitation wavelengths from 280 to 480 nm in an interval of 20 nm. The emission wavelength positions are found to red shift with increasing excitation wavelength, and the fluorescence intensity shows an increasing trend from 280 to 380 nm then decreasing from 380 to 480 nm. The GQDs can reach the maximum fluorescence intensity at an excitation wavelength near 360 nm (Figure S2a, Supporting Information); nevertheless, the maximum excitation wavelength of PEG-GQDs is around 380 nm (Figure 2g). Thus, both GQDs and PEG-GQDs also show a typical excitation wavelength dependence of the luminescence.

The fluorescence intensity of PEG-GQDs was found to increase by 40% in comparison to that of GQDs. PEG is selected to modify the defected surface of GQDs to eliminate the defect state luminescence and to create more exciton luminescence, thereby improving the luminescence efficiency of GQDs. Some studies have shown that different GQDs luminescence colors are related to multitudinous carbon sources (such as carbon fiber, graphite, and graphene oxide).26−28 The luminescence of PEG-GQDs derived from cane molasses in the present work is dominated by indigo blue light. The inset in Figure 2f is the fluorescence photographs of the PEG-GQDs on the right side and the GQDs on the left side under the UV lamp (λ = 365 nm); as can be seen, PEG-GQDs can emit brighter indigo blue fluorescent light in comparison to GQDs. The highest fluorescence QY of the obtained PEG-GQDs was determined to be 21.32%, which is much higher than that of the GQDs (10.44%) and the previous report of C-dots (5.8%),29 which also focuses on cane molasses as a carbon source. This implied that the effective passivation of GQDs surfaces with PEG significantly enhanced the fluorescence QY of GQDs. Moreover, the PEG capping on the outside of GQDs was found to change the fluorescence decay lifetime of GQDs. The fluorescence lifetime of GQDs is prolonged from 2.09 to 2.25 ns (as shown in Table 1). This may be the result of the conjugated aromatic structure of GQDs being modified by PEG, forming an electron delocalization field by combining the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy levels of PEG ligand with the conductive band-edge energy of GQDs. The excited electron of PEG-GQDs with a more stable environment was supplied from the electron delocalized field, thus the fluorescence lifetime of PEG-GQDs is prolonged.30

Table 1. Fluorescence Decay Time and Pre-Exponential Factor of GQDs and PEG-GQDs.

| parameter | τ1 (ns) | τ2 (ns) | A1 | A2 | τave (ns) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GQDs | 1.10 | 3.67 | 18 671.88 | 3499.49 | 2.09 |

| PEG-GQDs | 1.80 | 10.30 | 11 928.71 | 268.85 | 2.77 |

| PEG-GQDs-Fe3+ | 1.36 | 4.17 | 36 188.45 | 2212.06 | 1.80 |

To explore the effect of PEG addition on the luminescence efficiency of PEG-GQDs, different dilution factors were chosen to passivate the surface of GQDs. It was found that the fluorescence intensity was the highest when the GQDs solution was diluted 50 times with PEG (Figure 2h). It seemed that a complete encapsulation of GQDs defects was not achieved when the PEG content is too low, and the excessive amount of PEG may affect the emission of the characteristic peak of GQDs, giving rise to lower fluorescence intensity.

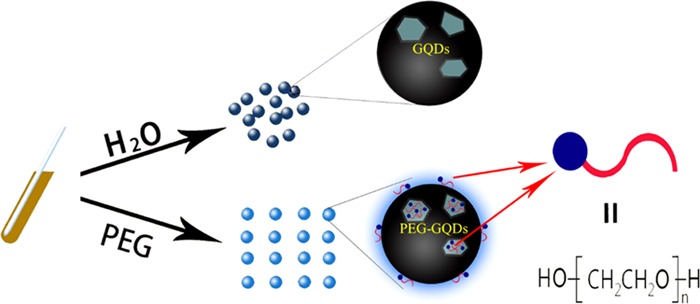

PEG is widely used in the field of biomedicine because of its biocompatibility, nontoxicity, antigen-free, and nonimmune characteristics.31 PEG comprises two chemical groups: one is hydrophilic polar groups and the other is oily nonpolar groups.32 When the surface of GQDs is modified by PEG, the nonpolar pro-oil groups are adsorbed to the surface of GQDs by the exchange of coordination bonds, which allows good permeability and good biocompatibility of cells. The polar hydrophilic group is compatible with water; the surface modification of GQDs by PEG can also reduce the surface tension of the GQDs, which changes its surface properties and makes the PEG-GQDs more stable. On the other hand, the long tail end can form spatial resistance to water molecules on the surface of PEG-GQDs, which results in PEG-GQDs in the water to have a large repulsive volume, thus preventing the agglomeration of GQDs.33 Thus, the surface modification of PEG can also result in good water solubility, good dispersion, and few defects in luminescent materials, which contribute to improving the stability and the fluorescence efficiency of GQDs; the function mechanism of PEG is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the function of PEG for GQDs.

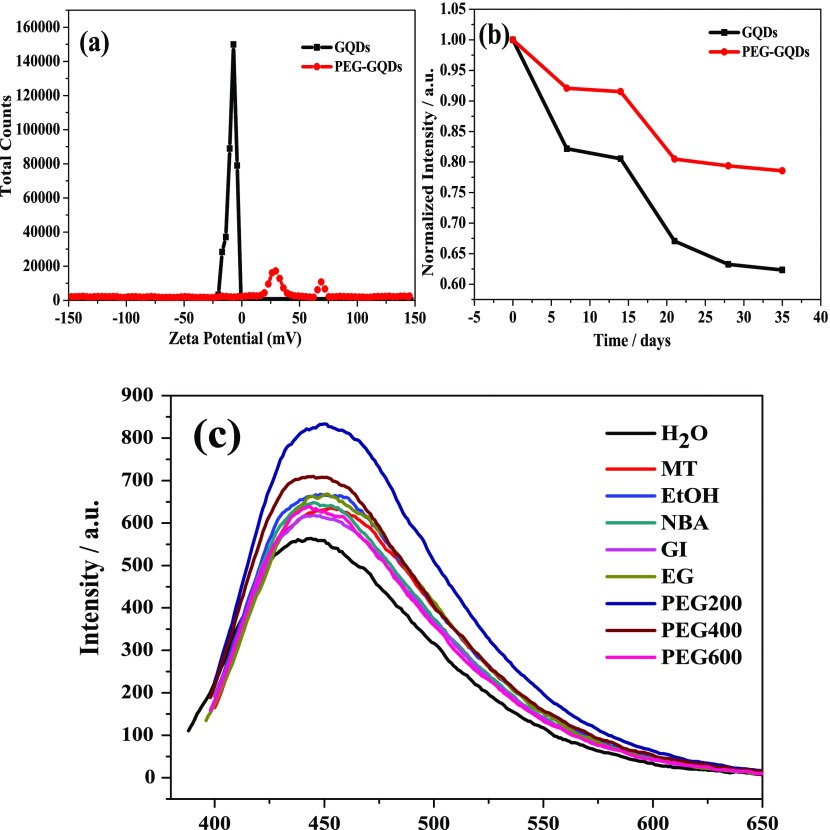

ζ-potential is an important index to characterize the stability of product dispersion. The lower the absolute value of the ζ-potential, the more molecules or particles in the system coagulate.34 The ζ-potential plot in Figure 4a shows that PEG-GQDs show two peaks at 30 and 70 mV in the positive electric region, while GQDs display only one peak at −7 mV in the negative electric region. Clearly, PEG-GQDs show a bigger potential than the negatively charged GQDs in terms of absolute value, indicating that PEG-GQDs have better stability compared to that of GQDs. Figure 4b demonstrates the fluorescence intensity change of PEG-GQDs and GQDs within 35 days, the less change in the fluorescence intensity of PEG-GQDs further demonstrates that the stability of PEG-GQDs is significantly better than that of GQDs.

Figure 4.

(a) ζ-potentials of GQDs and PEG-GQDs. (b) Stability of GQDs and PEG-GQDs for 35 days. (c) Fluorescence emission spectra of passivated GQDs under different modifiers.

To further test if the above mechanism is rational and universal, methanol (MT), ethanol (EtOH), n-butyl alcohol (NBA), glycerol (GI), ethylene glycol (EG), PEG-400, and PEG-600 were respectively selected for the fluorescence emission spectrum testing experiments. As can be seen in Figure 4c, the fluorescence intensity of GQDs modified by these passivators was found to increase compared to that of the unmodified GQDs, indicating that the surface of GQDs can be passivated by passivators with a hydroxyl group. Among all the passivators in this experiment, GQDs passivated by PEG-200 show a much higher fluorescence intensity than other alcohols, probably because its long-chain polymer structure can achieve a tighter coating of the inner layer GQDs, which is in contrast to micromolecules without a long-chain structure, such as MT, EtOH, NBA, GI, and EG, and because the hydroxyl values for PEG-400 and PEG-600 are far less than that of PEG-200.35 PEG-200 is thus considered to be the best choice for passivating GQDs in this paper.

Sensitivity Detection of Metal Ions

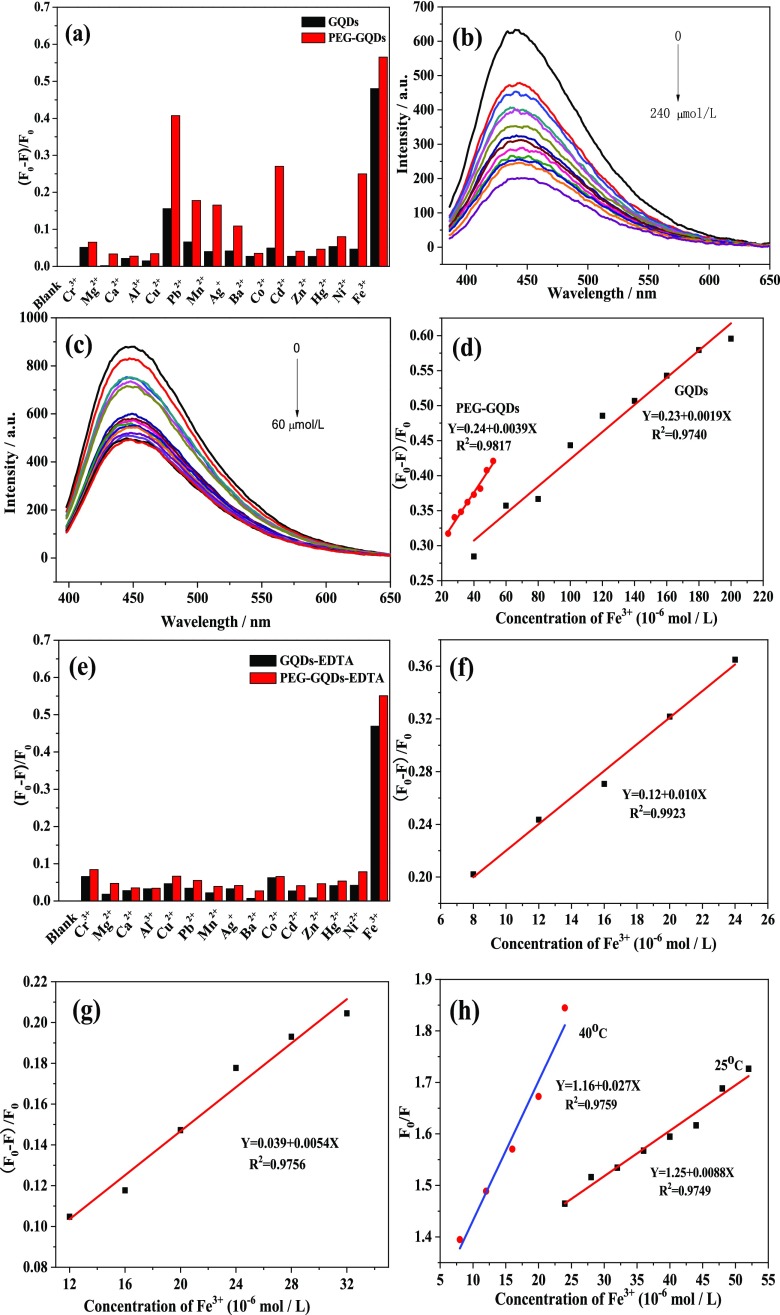

The characterization of PEG-GQDs promises the feasibility of an application. Here, to develop a fluorescence quenching method for metal ions sensing, the fluorescence emission spectra of PEG-GQDs and GQDs homogeneous solutions containing 400 μM various single-metal ions (Cr3+, Ca2+, Al3+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Mn2+, Ag+, Ba2+, Co2+, Cd2+, Zn2+, Hg2+, Fe3+, Mg2+, Ni2+) were scanned with a 376 nm excitation wavelength, respectively. The (F0 – F)/F0 bar diagram of the PEG-GQDs and the GQDs with the above ions is shown in Figure 5a, where F and F0 refer to the fluorescence intensities in the presence and absence of metal ions, respectively. As can be seen in Figure 5a, the fluorescence of PEG-GQDs is greatly quenched by several paramagnetic transition-metal ions such as Fe3+, Cu2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Pb2+, and Mn2+, among which the quenching degree of Fe3+ is the highest. Figure 5a also shows that the quenching degree of the PEG-GQDs by all metal ions screened in the present work is greater than that of GQDs.

Figure 5.

(a) Fluorescence responses of GQDs and PEG-GQDs to the different metal ions in the absence of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). (b) Fluorescence emission spectra of GQDs quenched by different concentrations of Fe3+ (from 0 to 240 μM) in a homogeneous solution. (c) Fluorescence emission spectra of PEG-GQDs quenched by different concentrations of Fe3+ (from 0 to 60 μM) in a homogeneous solution. (d) Calibration curves of the degree of fluorescence quenching [(F0 – F)/F0] of GQDs and PEG-GQDs versus Fe3+ ions concentration. (e) Fluorescence responses of GQDs and PEG-GQDs to different metal ions in the presence of EDTA. Calibration curves of the degree of fluorescence quenching [(F0 – F)/F0] of (f) PEG-GQDs and (g) GQDs versus Fe3+ ions concentration in the presence of EDTA, respectively. (h) Stern–Volmer curve for fluorescence quenching of PEG-GQDs by Fe3+ at different temperatures.

The fluorescence intensity changes of the GQDs and the PEG-GQDs in the solutions with different concentrations of Fe3+ are displayed in Figure 5b,c, respectively. A continuous decreasing trend with gradual increase in the concentration of Fe3+ in the solution from 0 to 240 μM for the GQDs and from 0 to 60 μM for the PEG-GQDs was observed, suggesting that the fluorescence intensity of the GQDs and the PEG-GQDs is sensitive to Fe3+. The calibration curves of the degree of fluorescence quenching (F0 – F)/F0 of both GQDs and PEG-GQDs versus the concentration of Fe3+ ions are illustrated in Figure 5d, which displays a good linear relationship for the GQDs in the concentration range of 40–200 μM with a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.97, and a good linear concentration range and R2 value for PEG-GQDs are 24–52 μM and 0.98, respectively. The limit of detections (LODs) of Fe3+ are estimated to be 30 μM for GQDs and 15 μM for PEG-GQDs. The Fe3+ detection limit was defined as LODs = 3σ/m, where σ is the standard deviation and m is the slope of the line in the linear response region of the calibration curve. Similarly, the detection limit of other metal ions are also determined using the above computing method with the PEG-GQDs system. The linear concentration range for the detection of Cu2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Mn2+, and Pb2+ by PEG-GQDs in single-metal ion solution is 20–52, 40–70, 60–180, 120–190, and 100–280 μM, respectively, and the corresponding LODs are 15.73, 23, 59.60, 80.69, and 93.95 μM, respectively (Figure S2b–f, Supporting Information).

Selective Detection of Fe3+ for PEG-GQDs

Iron is an indispensable element for the normal operation of life. Hence, it is very crucial to be able to conduct selective and quantitative detection of Fe3+ ions in a solution mixture with multiple metal ions. To avoid interference from other ions, the experiment was carried out by adding EDTA in both PEG-GQDs and GQDs sensing systems with single metal ions, respectively. EDTA plays the role of a complex agent to mask the effects of other metal ions. Figure 5e shows that in the presence of 4 mM EDTA, all metal ions (0.01 M) in our experiment except for Fe3+ have little effect on the fluorescence of both PEG-GQDs and GQDs, which demonstrates that the sensing systems have high selectivity for Fe3+.

Quantitative analysis results of Fe3+ in multifarious metal ion solution (Cr3+, Ca2+, Al3+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Mn2+, Ag+, Ba2+, Co2+, Cd2+, Zn2+, Hg2+, Mg2+, Ni2+, 0.01 M) in the presence of 4 mM EDTA for PEG-GQDs and GQDs are shown in Figure 5f,g, respectively. In the PEG-GQDs system, the linear concentration range for Fe3+ detection is 8–24 μM, with R2 of 0.99, and the LODs can reach 5.77 μM, which is even higher than that in the case of Fe3+ alone and the previous report by Ananthanarayanan et al. (LODs ≈ 7.22 μM).36 For the GQDs system, the linear concentration range is 12–32 μM, with R2 of 0.97, and the LODs can reach 10.78 μM, which also shows high selectivity and sensitivity like PEG-GQDs.

Fluorescence Quenching Mechanism of PEG-GQDs

To study whether the above-mentioned fluorescence quenching mechanism of PEG-GQDs by Fe3+ is dynamic or static, the effect of temperature on the quenching constant, fluorescence lifetime, and UV–vis absorption spectra were also studied in the present work. Dynamic quenching is associated with diffusion, the viscosity of the solution decreases, and the motion of the molecule accelerates when the temperature increases, resulting in an increase in diffusion coefficient and thus an increase in the molecule quenching constant. According to the Stern–Volmer equation F0/F = 1 + KSVτ0 [C] (where F0 and F are the fluorescence intensities of PEG-GQDs in the absence and presence of Fe3+, respectively, KSV is the quenching constant, τ0 is the lifetime of PEG-GQDs without Fe3+, [C] is the concentration of Fe3+), KSV increases with temperature if it is dynamic quenching. Besides, since the collision of fluorescence molecules and quenching agent only affects the excitation state of fluorescence molecules, the absorption spectrum of fluorescence molecules will not change, while the lifetime of the excitation state of fluorescence molecules will change in the presence of quenching agent.37Figure 5h shows that the slope KSV rises from 0.009 to 0.027 when the temperature is elevated from 25 to 40 °C. The weighted average fluorescence lifetime calculated from the fluorescence decay curves (Figure S3a, Supporting Information) of PEG-GQDs and PEG-GQDs-Fe3+ systems is 2.25 and 1.80 ns (Table 1), respectively. So, the characteristics of the increase of KSV, the decrease of fluorescence lifetime and the almost invariant UV–vis absorption spectra of PEG-GQDs (Figure S3b, Supporting Information) can demonstrate that the mechanism of quenching of PEG-GQDs by Fe3+ is dynamic.

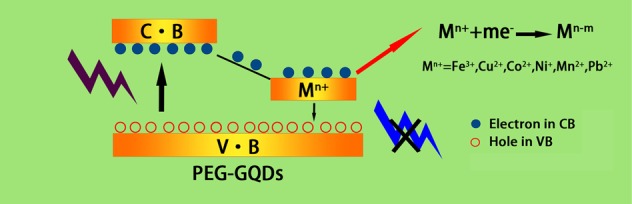

In the case of a dynamic quenching process, the excited-state molecule of the fluorescent material loses its excitation energy by the mechanism of energy transfer or charge transfer through the collision with the quenching agent molecule and returns to the ground state. Hence, this fluorescence quenching phenomenon may be ascribed to the energy transfer caused by the collision of the PEG-GQDs and metal ions, during which the energy of PEG-GQDs is transferred from the conduction band to the metal ions, leading to a decrease in the fluorescence intensity,38 as shown in Figure 6. In addition, the −OH groups on the surface of PEG-GQDs are able to coordinate with metal ions forming metal hydroxides,39,40 which results in aggregation between PEG-GQDs, giving rise to decrease in fluorescence intensity. These features of PEG-GQDs could contribute to higher sensitivity in the detection of metal ions compared with GQDs.

Figure 6.

Quenching mechanism of metal ions of PEG-GQDs.

Detection of Fe3+ in Healthy Human Serum

To explore the feasibility of the PEG-GQDs as a tool for the quantitative analysis of Fe3+, healthy human serum was used for verification in this experiment under the above-mentioned optimal conditions. The average recovery of adding standard sample is close to 100% and the RSD is less than 5%, as shown in Table 2, indicating the synthesized PEG-GQDs can meet the requirements of detecting Fe3+ in serum.

Table 2. Detection of Fe3+ in Healthy Human Serum by PEG-GQDs.

| sample | added (μmol/L) | found (μmol/L) | recovery (%) | RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| healthy | 0 | 17.45 | ||

| human | 2 | 19.59 | 107.07 | |

| serum | 2 | 19.38 | 96.40 | 4.34 |

| 2 | 19.52 | 103.59 |

Conclusions

In summary, the blue fluorescent PEG-GQDs were smoothly synthesized using cane molasses as the source of carbon by the hydrothermal method, followed by passivation. PEG-GQDs showed more uniform and dispersed spherical morphology, higher stability, longer fluorescence lifetime, and higher fluorescence intensity and quantum yield than GQDs. The PEG-GQDs can selectively detect Fe3+ in a mixture solution with multiple metal ions in the presence of EDTA, which can be realized by the detection of Fe3+ in serum. The GQDs passivated by PEG with high QY can meet the requirements for the multifunctional applications.

Experimental Section

Materials

Cane molasses was provided by Ganhua Group Co., Ltd., Guigang, Guangxi, China. Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) including PEG-200, PEG-400, and PEG-600, methanol (MT), ethanol (EtOH), n-butyl alcohol (NBA), glycerol (GI), and ethylene glycol (EG) were purchased from Xilong Scientific, Guangdong, China. Analytical grade EDTA and AgCl, AlCl3, BaCl2, FeCl3, CdCl2, Co(NO3)2, CrCl3, CuCl2, FeCl3, Hg(NO3)2, MgCl2, MnCl2, Ni(NO3)2, Zn(NO3)2, and (CH3COO)2Pb were also purchased from Xilong Chemical, Guangdong, China. All chemicals in our work were used strictly according to regulations. All experiments used ultrapure water (UP water). PEG-200 was used in all experiments except those in which the type of poly(ethylene glycol) was specified. Blood sample (provided by the inspection department of Guilin University of Technology Hospital) was centrifuged at high speed (3500 r/min) for 10 min, and serum was collected for Fe3+ analysis.

Synthesis of GQDs and PEG-GQDs

Typically, GQDs were prepared by the hydrothermal method. Cane molasses (1.8 mL) was dissolved in 28.2 mL of ultrapure water to form a homogeneous aqueous solution and then ultrasonicated and centrifuged, each for 10 min, respectively. Twenty milliliters of cane molasses supernatant was then transferred to a 30 mL steel high-pressure reactor and heated in a hot-air oven at 190 °C for 24 h. After completion of the hydrothermal process, the reactor was allowed to cool down, and the obtained carbon slag residue was separated from the initial product by filtration using a 0.2 μm filter paper to acquire GQDs primary liquid. GQDs solution was then obtained by diluting the GQDs primary liquid with UP water for 50 times. PEG-GQDs solution with high-fluorescence QY for metal ions detection was produced by diluting the GQDs primary liquid with PEG-200 for 50 times.

Characterization Methods

Various physicochemical techniques were used to determine the surface morphology, chemical component, and optical properties of the synthesized GQDs and PEG-GQDs. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was executed on a JEM-2100F TEM at 200 kV. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) observation was executed with Ntegra Prima SPM. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were collected using a Thermo Nexus 470FT-IR spectrometer (KBr disk). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was carried out using ESCALAB250Xi. The fluorescence lifetime of the synthetic samples was collected using an FLS980 fluorometer. UV–vis absorption and fluorescence spectra were recorded by a UV-3600 UV–vis–NIR spectrophotometer and a VARIAN Cary 100 fluorospectrophotometer (the voltage is set to 550 V and the slit widths of excitation and emission are both set to 5 nm). Fluorescence quantum yield (QY) was detected using quinine sulfate as the standard (QY = 54% in 0.1 M H2SO4). The ζ-potential of GQDs and PEG-GQDs was collected on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS (ZS 90, UK).

Fluorescence Detection of Metal Ions

In the experiment of sensing capability of PEG-GQDs toward metal ions, 100 μL GQDs primary liquid was mixed with 200 μL of metal ions (Cr3+, Ca2+, Al3+, Cu2+, Pb2+, Mn2+, Ag+, Ba2+, Co2+, Cd2+, Zn2+, Hg2+, Fe3+, Mg2+, Ni2+) solutions (0.01 M), respectively. Then, the solution was fixed to 5 mL with PEG as the diluent with vigorous shaking at room temperature. Fluorescence emission spectra of each mixture solution were collected with an excitation wavelength at 376 nm to verify the responses of the above ions to the fluorescence of PEG-GQDs after 10 min. As a reference, the sensing capability of GQDs toward Fe3+ was also investigated using UP water as the diluent following the same procedure.

For the masking experiment phase, the difference from the experiment of sensing capability of PEG-GQDs and GQDs toward metal ions is the addition of 200 μL of EDTA (0.1 M) to prove the masking effect before adding different metal ions. One hundred microliters of healthy human serum was diluted to 5 mL with PEG after adding 200 μL of EDTA (0.1 M) at room temperature to quantify the amount of Fe3+ by the standard addition method, which means that a certain amount of Fe3+ is added to the serum. More detailed experimental procedures can be seen in the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51564009 and 51468011) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi province (No. 2018JJA160029).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c00098.

GQDs fluorescence probe for the detection of metal ions at different conditions; optimum synthesis conditions of GQDs; excitation wavelength dependence of GQDs, the degree of fluorescence quenching varies with the concentration of Cu2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Mn2+, and Pb2+ for PEG-GQDs; fluorescence decay curve of the GQDs, PEG-GQDs, and PEG-GQDs in the presence of Fe3+, UV–vis absorption spectra of PEG-GQDs in the presence of Fe3+, and the superposition of the UV–vis absorption spectra of PEG-GQDs and Fe3+ solution (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sharma V.; Tiwari P.; Mobin S. M. Sustainable carbon-dots: recent advances in green carbon dots for sensing and bioimaging. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 8904–8924. 10.1039/C7TB02484C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju B.; Wang Y.; Zhang Y. M.; Zhang T.; Lu Z. H.; Li M. J.; Zhang S. X. A. Photostable and Low-Toxic Yellow-Green Carbon Dots for Highly Selective Detection of Explosive 2,4,6-Trinitrophenol Based on the Dual Electron Transfer Mechanism. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 13040–13047. 10.1021/acsami.8b02330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X. H.; An X. Q.; Li L. L. Easy synthesis of highly fluorescent carbon dots from albumin and their photoluminescent mechanism and biological imaging applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 58, 730–736. 10.1016/j.msec.2015.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J. Q.; Sheng Y. Z.; Zhang J. X.; Wei J. M.; Huang P.; Zhang X.; Feng B. X. Preparation of carbon quantum dots/TiO2 nanotubes composites and their visible light catalytic applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 18082–18086. 10.1039/C4TA03528C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. P.; Wu X. Q.; Guo S. J.; Han M. M.; Zhou Y. J.; Sun Y.; Huang H.; Liu Y.; Kang Z. H. Mesoporous nitrogen, sulfur co-doped carbon dots/CoS hybrid as an efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 2717–2723. 10.1039/C6TA09580A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L.; Yong K. T.; Liu L. W.; Roy I.; Hu R.; Zhu J.; Cai H. X.; Law W. C.; Liu J. W.; Wang K.; Liu J.; Liu Y. Q.; Hu Y. Z.; Zhang X. H.; Swihart M. T.; Prasad P. N. A pilot study in non-human primates shows no adverse response to intravenous injection of quantum dots. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 453–458. 10.1038/nnano.2012.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Gao X.; Su X. G. In vitro and in vivo imaging with quantum dots. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 397, 1397–1415. 10.1007/s00216-010-3481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari D. K.; Jin T.; Behari J. Bio-distribution and toxicity assessment of intravenously injected anti-HER2 antibody conjugated CdSe/ZnS quantum dots in Wistar rats. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 463–475. 10.2147/IJN.S15124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.; Guo G. L.; Chen D.; Liu Z. D.; Zheng X. H.; Xu A. L.; Yang S. W.; Ding G. Q. Facile and Highly Effective Synthesis of Controllable Lattice Sulfur-Doped graphene Quantum Dots via Hydrothermal Treatment of Durian. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 5750–5759. 10.1021/acsami.7b16002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. F.; Yu J. F.; Zhang X.; Li N.; Liu B.; Li Y. Y.; Wang Y. H.; Wang W. X.; Li Y. Z.; Zhang L. C.; Dissanayake S.; Suib S. L.; Sun L. Y. Large-Scale and Controllable Synthesis of graphene Quantum Dots from Rice Husk Biomass: A Comprehensive Utilization Strategy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 1434–1439. 10.1021/acsami.5b10660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namdari P.; Negahdari B.; Eatemadi A. Synthesis, properties and biomedical applications of carbon-based quantum dots: An updated review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 87, 209–222. 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.12.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. F.; Lv G.; Hu W. M.; Li D. J.; Chen S. N.; Dai Z. X. Synthesis and applications of graphene quantum dots: a review. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2018, 7, 157–185. 10.1515/ntrev-2017-0199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. F.; Hu A. G. Carbon quantum dots: synthesis, properties and applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 6921–6939. 10.1039/C4TC00988F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S. J.; Zhang J. H.; Tang S. J.; Qiao C. Y.; Wang L.; Wang H. Y.; Liu X.; Li B.; Li Y. F.; Yu W. L.; Wang X. F.; Sun H. C.; Yang B. Surface Chemistry Routes to Modulate the Photoluminescence of graphene Quantum Dots: From Fluorescence Mechanism to Up-Conversion bioimaging Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 4732–4740. 10.1002/adfm.201201499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. J.; Li C.; Ren Y. J.; Sun X. B.; Pan W.; Li Y. H.; Wang J. P.; Wang W. J. Carbon dots: surface engineering and applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 5772–5788. 10.1039/C6TB00976J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H. J.; Gao N.; Wu L.; Ren J. S.; Wei W. L.; Qu X. G. Highly photoluminescent Amino-Functionalized graphene Quantum Dots Used for Sensing Copper Ions. Chem. - Eur. J. 2013, 19, 13362–13368. 10.1002/Chem.201302268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Han Y.; Zhu J.; Zhai Y.; Dong S. Simple and Sensitive Fluorescent and Electrochemical Trinitrotoluene Sensors Based on Aqueous Carbon Dots. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 2033–2036. 10.1021/ac5043686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y.-C.; Zhao Y.-D.; Song Y.-Y.; Tan F.; Fang B.-Y.; Li C. Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dot for direct fluorescence detection of Al3+ in aqueous media and living cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 100, 41–48. 10.1016/j.bios.2017.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi B.; Zhang L.; Lan C.; Zhao J.; Su Y.; Zhao S. One-pot green synthesis of oxygen-rich nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots and their potential application in pH-sensitive photoluminescence and detection of mercury(II) ions. Talanta 2015, 142, 131–139. 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edison T.; Atchudan R.; Shim J. J.; Kalimuthu S.; Ahn B. C.; Lee Y. R. Turn-off fluorescence sensor for the detection of ferric ion in water using green synthesized N-doped carbon dots and its bio-imaging. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 2016, 158, 235–242. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Qin A.; Chen S.; Liao L.; Qin J.; Zhang K. Manganese(II) enhanced fluorescent nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots: a facile and efficient synthesis and their applications for bioimaging and detection of Hg2+ ions. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 5902–5911. 10.1039/C7RA12133D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchudan R.; Edison T.; Aseer K. R.; Perumal S.; Karthik N.; Lee Y. R. Highly fluorescent nitrogen-doped carbon dots derived from Phyllanthus acidus utilized as a fluorescent probe for label-free selective detection of Fe3+ ions, live cell imaging and fluorescent ink. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 99, 303–311. 10.1016/j.bios.2017.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X. L.; Zhang W. G.; Han Y.; Chen X. M.; Zhu L.; Tang W. Z.; Wang J. L.; Yue T. L.; Li Z. H. N,S co-doped carbon dots based fluorescent “on-off-on” sensor for determination of ascorbic acid in common fruits. Food Chem. 2018, 258, 214–221. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Hou D. S.; Manzano H.; Orozco C. A.; Geng G. Q.; Monteiro P. J. M.; Liu J. P. Interfacial Connection Mechanisms in Calcium-Silicate-Hydrates/Polymer Nanocomposites: A Molecular Dynamics Study. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 41014–41025. 10.1021/acsami.7b12795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Bi W. T.; Liu L. Y.; Li Z.; Huang X. T. Preparation and characterization of ZnO nanospindles and ZnO@ZnS core-shell microspindles. Colloids Surf., A 2009, 334, 160–164. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2008.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C. G.; Xing M.; Wu Q. L. A universal facile synthesis of nitrogen and sulfur co-doped carbon dots from cellulose-based biowaste for fluorescent detection of Fe3+ ions and intracellular bioimaging. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2019, 99, 611–619. 10.1016/j.msec.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. L.; Jin L.; He X. B.; Huang X.; Xie M. L.; Wang C. F.; Zhang C. L.; Yang W. Q.; Meng F. B.; Lu J. Glowing stereocomplex biopolymers are generating power: polylactide/ carbon quantum dot hybrid nanofibers with high piezoresponse and multicolor luminescence. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 1810–1823. 10.1039/C8TA08593E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu P. P.; Tan K. J.; Chen Q.; Xiong J.; Gao L. X. Origins of Efficient Multiemission Luminescence in Carbon Dots. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 4732–4742. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b00870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G.; Chen X.; Wang C.; Zheng H. Y.; Huang Z. Q.; Chen D.; Xie H. H. photoluminescent carbon dots derived from sugarcane molasses: synthesis, properties, and applications. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 47840–47847. 10.1039/C7RA09002A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.; Xia H. B.; Wu S. L.; Zhang S. F. Prolonging the lifetime of excited electrons of QDs by capping them with pi-conjugated thiol ligands. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 2939–2943. 10.1039/C3TC32523G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari M.; Soltani M.; Naahidi S.; Karunaratne D. N.; Chen P. Nonviral Approach for Targeted Nucleic Acid Delivery. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 197–208. 10.2174/092986712803414141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronese F. M. Peptide and protein PEGylation: a review of problems and solutions. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 405–417. 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi Y.; Rai A.; Rai S. B. Energy transfer in Er:Eu:Yb co-doped tellurite glasses: Yb as enhancer and quencher. J. Lumin. 2009, 129, 629–633. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2009.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cha Y.; Shi X. J.; Wu F.; Zou H. N.; Chang C. T.; Guo Y. N.; Yuan M.; Yu C. P. Improving the stability of oil-in-water emulsions by using mussel myofibrillar proteins and lecithin as emulsifiers and high-pressure homogenization. J. Food Eng. 2019, 258, 1–8. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2019.04.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sengwa R. J. Microwave dielectric relaxation and molecular dynamics in binary mixtures of poly(vinyl pyrrolidone)-poly(ethylene glycol)s in non-polar solvent. Polym. Int. 2003, 52, 1462–1467. 10.1002/pi.1244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ananthanarayanan A.; Wang X. W.; Routh P.; Sana B.; Lim S.; Kim D. H.; Lim K. H.; Li J.; Chen P. Facile Synthesis of graphene Quantum Dots from 3D graphene and their Application for Fe Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 3021–3026. 10.1002/adfm.201303441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zu F. L.; Yan F. Y.; Bai Z. J.; Xu J. X.; Wang Y. Y.; Huang Y. C.; Zhou X. G. The quenching of the fluorescence of carbon dots: A review on mechanisms and applications. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 1899–1914. 10.1007/s00604-017-2318-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. L.; Wang L.; Zhang H. C.; Liu Y.; Wang H. Y.; Kang Z. H.; Lee S. T. Graphitic carbon quantum dots as a fluorescent sensing platform for highly efficient detection of Fe3+ ions. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 3733–3738. 10.1039/c3ra23410j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tam T. V.; Trung N. B.; Kim H. R.; Chung J. S.; Choi W. M. One-pot synthesis of N-doped graphene quantum dots as a fluorescent sensing platform for Fe3+ ions detection. Sens. Actuators, B 2014, 202, 568–573. 10.1016/j.snb.2014.05.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. J.; Gan J. Synthesis of blue-photoluminescent graphene quantum dots/polystyrenic anion-exchange resin for Fe(III) detection. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 372, 145–151. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.02.248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.