Abstract

Background:

Individuals with drug convictions are at heightened risk of poor health, due in part to punitive public policies. This study tests the effects of message frames on: 1) public stigma towards individuals with felony drug convictions and 2) support for four policies in the United States (U.S.) affecting social determinants of health: mandatory minimum sentencing laws, ‘ban-the-box’ employment laws, and restrictions to supplemental nutrition and public housing programs.

Methods:

A randomized experiment (n=3,758) was conducted in April 2018 using a nationally representative online survey panel in the U.S. Participants were randomized to a no-exposure arm or one of nine exposure arms combining: 1) a description of the consequences of incarceration and community reentry framed in one of three ways: a public safety issue, a social justice issue or having an impact on the children of incarcerated individuals, 2) a narrative description of an individual released from prison, and 3) a picture depicting the race of the narrative subject. Logistic regression was used to assess effects of the frames.

Results:

Social justice and the impact on children framing lowered stigma measures and increased support for ban-the-box laws.

Conclusion:

These findings can inform the development of communication strategies to reduce stigma and advocacy efforts to support the elimination of punitive polices towards individuals with drug convictions.

Keywords: stigma, messaging, policy, criminal justice

INTRODUCTION

Fifteen percent of sentenced state prisoners in the United States (U.S.) were convicted of a drug offense in 2015 (US. Department of Justice, 2018), and 47% of U.S. sentenced federal prisoners were incarcerated for a drug offense in 2016 (US. Department of Justice, 2018). Upon release, individuals are at heightened risk of poor physical and mental health, homelessness, unemployment (Wildeman & Wang, 2017) and food insecurity (Wang et al., 2013) compared to the general population. In part, this may be due to certain U.S. policies directed toward people with felony drug convictions, including mandatory minimum sentencing laws, restrictions to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and public housing programs, and required disclosure of criminal history on employment applications, which may perpetuate and exacerbate the health disparities caused by mass incarceration. This article considers two key issues in debates around these policies: how to reduce public stigma towards individuals with felony drug convictions and how to increase public support for policies aimed at improving the social determinants of health of those released from prison following drug convictions and decrease support for punitive policies towards this population.

Policy Context

In recent years, four policies affecting those with prior drug convictions have been the subject of considerable public debate at the local, state and federal levels in the U.S: mandatory minimum sentencing, restrictions to food and housing assistance and requirements to disclose criminal justice status on employment applications. While evidence around these policies is still emerging, they specifically target individuals with histories of criminal justice involvement, particularly those with drug-related felony convictions.

Mandatory Minimum Sentencing

Mandatory minimum sentencing laws are policies enacted at the state and federal level that require minimum incarceration terms for individuals convicted of certain crimes (National Research Council, 2014). In 2018, the First Step Act eased mandatory minimum sentences for drug-related crimes in federal prisons, though funding and implementation is still in process (Haberman & Karni, 2019). Across the states, both harsher and more lenient mandatory minimum sentencing laws for drug-related crimes have been introduced as a response to the opioid epidemic (Lopez, 2017). Research across many disciplines suggests that lengthening sentencing via mandatory minimums may not be effective at reducing crime rates or drug use (National Research Council, 2014).

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Restrictions

Formerly known as the food stamp program, SNAP is the largest federal nutrition assistance program in the U.S. and provides participants with benefits to purchase eligible food at authorized retail food stores. States have been shifting away from policy enacted as part of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996, which placed a lifetime ban on SNAP eligibility for persons convicted of a drug felony. The law allows states to opt-out or modify this ban. From 2012 to 2015, five states eased and one state strengthened these SNAP restrictions (US Department of Agriculture, 2018). As of October 2017, 25 states and DC had completely opted out of the ban, 23 states had a modified ban, and five states had maintained the federal lifetime ban (US Department of Agriculture, 2018). Examples of modifications include: requiring participation in drug testing or treatment as a condition of participation in SNAP, imposing temporary disqualification periods or imposing disqualifications only on certain drug felony offenses (US Department of Agriculture, 2018). Research on the effects of these bans is limited, but suggests they may be associated with increases in food insecurity (Wang et al., 2013).

Public Housing Restrictions

A 2013 survey of the largest housing authorities in the U.S. found that 93% have some bans on public housing for those with prior drug convictions (Curtis, Garlington, & Schottenfeld, 2013). In 2015, the U.S. federal government issued guidance that discouraged blanket exclusion of individuals with drug convictions and left discretion on this matter to local housing authorities (US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2015). The effects of this guidance are not yet known. However, expanding access to public housing may have the potential to improve the wellbeing of individuals with prior felony drug convictions, as research suggests public housing is associated with reduced homelessness and recidivism among criminal justice involved populations (Gubits et al., 2015).

Ban-the-Box Employment Policies

Ban-the-box policies prohibit certain employers from inquiring about applicant’s criminal history until later in the hiring process. Thirty-five states and 150 cities in the U.S. have implemented laws that apply to either government agencies, government contractors or in some cases private employers (Avery, 2019). Early evidence on the effectiveness of these bans is mixed. Research suggests that the employment prospects of formerly incarcerated individuals can improve if they interact directly with a prospective employer (Pager, Western, & Sugie, 2009). This interaction is unlikely if they are screened out in early job application stages due to criminal history. However, recent evidence suggests that the enactment of ban-the-box can increase discrimination against of black applicants when criminal justice status is not disclosed (Agan & Starr, 2018; Doleac & Hansen, 2019).

Effects of Message Framing and Sympathetic Narratives

Understanding public stigma towards individuals with felony drug convictions may be particularly important to influencing public policy related to sentencing, employment and access to public benefits. Prior research from several countries indicates that individuals with a history of incarceration and individuals with a history of drug use are highly stigmatized (Barry, McGinty, Pescosolido, & Goldman, 2014; McGinty, Goldman, Pescosolido, & Barry, 2015; Schnittker & John, 2007; van Olphen, Eliason, Freudenberg, & Barnes, 2009; Yang, Wong, Grivel, & Hasin, 2017), though recent public opinion in the United States specifically on individuals with felony drug convictions is unknown. Research from several countries on a wide range of health-related topics, including criminal justice involvement, substance use disorder, obesity and tobacco use, have shown that stigma is associated with poorer health and social outcomes, exacerbation of health disparities, and lower public support for policies benefiting people experiencing these issues – but greater support for punitive policies targeting these stigmatized groups (Ahern, Stuber, & Galea, 2007; Evans-Polce, Castaldelli-Maia, Schomerus, & Evans-Lacko, 2015; Kane et al., 2019; Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2017; Kennedy-Hendricks, McGinty, & Barry, 2016; Puhl & Heuer, 2009; Schnittker & John, 2007).

Framing, or making certain aspects of an issue more salient, is evident in the news media and can influence public stigma towards a population and preferred policy solutions to a policy problem (Körner & Treloar, 2004; Hopwood, Brener, Frankland, & Treloar, 2010; Treloar & Fraser, 2007; Entman, 1993; Gollust, Lantz, & Ubel, 2009; Kahneman & Tversky, 1984; Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2019; McGinty, Webster, & Barry, 2013; Chong & Druckman, 2007). Prior research has shown that message frames that contradict stereotypes, elicit emotional responses and demonstrate structural barriers to success may reduce stigma and increase support for less punitive policies (Bachhuber, McGinty, Kennedy-Hendricks, Niederdeppe, & Barry, 2015; Gross, 2008; Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2016; McGinty et al., 2015). Consequence frames, or frames that highlight certain consequences of a public health issue over others, such as the impact of a problem on mortality versus economic consequences, have also been shown to affect the public’s policy preferences and shift the public’s views of the population affected by the problem (Gollust, Niederdeppe, & Barry, 2013; Iyengar, 1996; McGinty, Niederdeppe, Heley, & Barry, 2017; Schneider & Ingram, 1993).

Prior research also suggests that the use of sympathetic narratives, or stories about individuals, can elicit differing attitudes towards populations and policies compared to more general descriptions of social problems (Bachhuber et al., 2015; Gross, 2008; Niederdeppe, Heley, & Barry, 2015). While sympathetic narratives can increase audiences’ emotional engagement and humanize complex policy problems, they may also shift blame of a policy problem onto the individual (Iyengar, 1990). However, experiments that combine sympathetic narratives with contextual information have been shown to increase support for public health policies (Bachhuber et al., 2015; Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2016; McGinty et al., 2015; Niederdeppe et al., 2015).

Framing and Narrative Research Related to Criminal Justice Involved Populations

Research on the effects of message framing and sympathetic narratives related to criminal justice involved populations have largely focused on effects on public attitudes towards sentencing policy. A study examining the effects of consequence framing on sentencing policy towards non-violent drug offenders found that framing the criminal justice system as having a negative consequence on public safety increased support for eliminating incarceration for non-violent drug offenses, but framing the criminal justice system as having a negative impact on equity and social justice or children of incarcerated parents had no effect (Gottlieb, 2017). Frames that emphasize the racial disparities in incarceration have shown mixed effects on attitudes towards death penalty policies. Some results showed decreased support for the death penalty among white respondents (Peffley & Hurwitz, 2007), while other studies, including ones that also included a short description of an incarcerated individual, did not replicate this result (Bobo & Johnson, 2004; Butler, Nyhan, Montgomery, & Torres, 2018). Sympathetic narratives have also been shown to decrease support for mandatory minimum sentencing (Gross, 2008).

The race of incarcerated individuals has also influenced framing and narrative effects. Narratives featuring stories of black incarcerated individuals produced lower levels of support for eliminating mandatory minimum sentences compared to narratives featuring white incarcerated individuals (Gross, 2008). Another study exposed participants to a series of photographs of black and white incarcerated individuals and manipulated the racial composition of the photographs and found that participants who saw a higher proportion of photographs of black individuals preferred more punitive criminal justice policies (Hetey & Eberhardt, 2014). Framing criminal justice reform policy as positively affecting black communities versus just communities reduced support for criminal justice reforms among white respondents but not black respondents (Wozniak, 2019).

With the exception of Wozniak 2019, the studies examining framing and sympathetic narratives for criminal justice involved populations used convenience sampling, or non-probability sampling where participants are selected for their accessibility, and therefore may be biased due to over and under representation of certain populations and not generalizable to the overall U.S. population. This study builds upon this prior research by using a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults to examine the effects of consequence frames, a sympathetic narrative and an image depicting the race of the narrative subject. We examine the effects of these exposures on public stigma and attitudes towards sentencing, employment, housing and nutrition policy towards individuals with a felony drug conviction.

In this study, we provide national estimates in 2018 of public support for four policies – eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing, enacting ban-the-box policies, and removing restrictions to SNAP and public housing among U.S. adults. Recent media coverage of mandatory minimum sentencing, SNAP and housing restrictions and disclosure of criminal history on job applications have highlighted these policies’ consequences on three areas 1) public safety 2) equity and social justice and 3) the wellbeing of the children of parents with prior drug convictions (Applebaum, 2015; Born, 2018; Lopez, 2017). The public safety frame argues that eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing, enacting ban-the-box policies, and removing restrictions to SNAP and public housing have the potential to improve public safety by improving the wellbeing of individuals following incarceration and thereby reducing the likelihood of individuals committing future crimes. The social justice frame argues that the criminal justice system disproportionately incarcerates marginalized populations, and punitive policies perpetuate hardships facing already vulnerable groups. Finally, punitive policies can have detrimental long-term impacts on the children of incarcerated individuals by extending the sentence of the incarcerated parent and limiting economic and government assistance resources available to the child during and following the parent’s release.

We also tested the effects of these three consequence frames with and without a sympathetic narrative that includes an image depicting the narrative subject’s race as a young black man or a young white man. We examined whether these message frames affected: 1) public stigma towards individuals with felony drug convictions and 2) public support for eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing, enacting ban-the-box policies, and removing restrictions to SNAP and public housing.

First, we hypothesize that compared to a no exposure control arm, exposure to the consequence frames (public safety, social justice and impact on children) will: 1) decrease stigma towards individuals with a felony drug conviction and 2) increase policy support for less punitive policies. Second, we hypothesize that compared to the consequence frames alone, the consequence frames in combination with a sympathetic narrative will have a greater 1) decrease in stigma towards individuals with a felony drug conviction and 2) increase in policy support for less punitive policies. Finally, we hypothesize that compared to narratives where the subject’s race is depicted as white, narratives where the subject’s race is depicted as black will be associated with smaller 1) decreases in stigma towards individuals with a felony drug conviction and 2) increases in policy support for less punitive policies.

METHODS

Design and Participants

We conducted a 10-arm randomized experiment using the nationally representative NORC’s AmeriSpeak survey research panel of U.S. adults made available through the National Science Foundation Time Series Experiments in the Social Science program. Participants were randomly assigned to one of nine experimental groups or a no-exposure control group. The experimental groups, listed in Table 1, were exposed to one or more of the following elements: 1) a consequence frame highlighting one of the three types of consequences (public safety, social justice or impact on children), 2) a short sympathetic narrative, and 3) a picture depicting the race of the subject of the narrative (a black man or a white man). The no-exposure control group only answered outcome questions.

Table 1.

Study Arms for the Randomized Experiment (n=3,758)

| Group Number | Exposure |

|---|---|

| Group 1 | No Exposure Control (n=1,070) |

| Group 2 | Public Safety Consequence Frame (n=287) |

| Group 3 | Social Justice Consequence Frame (n=287) |

| Group 4 | Impact on Children Consequence Frame (n=288) |

| Group 5 | Public Safety Consequence Frame + Narrative + Image of Black Narrative Subject (n=309) |

| Group 6 | Social Justice Consequence Frame + Narrative + Image of Black Narrative Subject (n=305) |

| Group 7 | Impact on Children Consequence Frame + Narrative + Image of Black Narrative Subject (n=292) |

| Group 8 | Public Safety Consequence Frame + Narrative + Image of White Narrative Subject (n=309) |

| Group 9 | Social Justice Consequence Frame + Narrative + Image of White Narrative Subject (n=300) |

| Group 10 | Impact on Children Consequence Frame + Narrative + Image of White Narrative Subject (n=311) |

The probability-based AmeriSpeak panel included 25,000 households assembled from an address-based sample frame of over 97 percent of U.S. households, and has been used in prior public health research (Barry et al., 2018; Bye, Ghirardelli, & Fontes, 2016; Dennis, J. Michael, 2017) For this study, a random sample of participants were drawn from the 25,000 member panel, and the proportion of panel members among that sample that completed the experiment, was 52%. The experiment was fielded from April 4th −16th, 2018. We excluded participants (n=306) with a completion times less than the 0.05th percentile (13 seconds) or greater than 99.5 percentile (491 minutes), which likely indicate failure to read the exposure text or interruption during experiment completion. The final analytic sample included 3,758 individuals.

Measures

Outcome Variables

Outcomes included measures of public stigma towards individuals with a felony drug conviction (two items) and support for eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing, enacting ban-the-box policies, and removing restrictions to SNAP and public housing (four items). Full outcome questions and response categories are listed in Appendix A.

Public stigma outcomes included a measure of social distance and a measure of respondents’ perception of an individual’s ability to rehabilitate. The measure of social distance was adapted from the General Social Survey, (Pescosolido et al., 2010) where respondents were asked “How willing would you be to move next door to someone convicted of a felony drug crime? Perceived ability to rehabilitate was assessed with the following question: “Most people convicted of felony drug crimes can return to productive lives in the community with the right kind of help. Do you agree or disagree with this statement?”

Questions assessing policy support provided a brief one sentence description of each policy (eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing, eliminating restrictions to SNAP, eliminating restrictions to public housing and enacting ban-the-box) and then asked respondents if they favored or opposed the policy for individuals with felony drug convictions.

To assess support for eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing, respondents were asked, “Some states have mandatory minimum sentencing laws that require minimum prison sentences for people convicted of felony drug crimes. In other states judges are given more leeway to decide prison sentences on a case-by-case basis. Do you favor or oppose eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing laws for people convicted of felony drug crimes?”

To assess support for eliminating restrictions to SNAP, respondents were asked, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as SNAP or the food stamp program, helps low income families purchase food. In some states people convicted of felony drug crimes are banned from getting SNAP. Do you favor or oppose a law to allow people convicted of felony drug crimes to receive SNAP?”

To assess support for eliminating restrictions to public housing, respondents were asked, “In some states people convicted of felony drug crimes are banned from housing assistance programs that help with the cost of housing. Do you favor or oppose a law to allow people convicted of felony drug crimes to access housing assistance programs?”

To assess support for enacting ban-the-box policies, respondents were asked, “Many employers require that people convicted of felony drug crimes report their prior convictions on job applications. Some states and cities are passing ban-the-box laws that prohibit asking about convictions until later stages of the job application process. Do you favor or oppose ban-the-box laws that prevent employers from asking job applicants about felony drug convictions until later phases of the job application process?”

All responses to public stigma and policy support questions were recorded using 5-point Likert scales. The order of the block of questions (public stigma, policy support) and the order of the questions within each block were randomized.

Independent Variables

We tested the effects of three message framing elements: a consequence frame, a narrative and an image of the narrative subject which are listed in Table 2. Experimental groups 2–4 viewed a paragraph of contextual information framed using one of three consequence frames: public safety, social justice, or impact on children. Experimental groups 5–7 read the same consequence frames followed by a short narrative of a man who had been recently released following incarceration for a felony drug conviction. These narratives were accompanied by a picture depicting the subject of the narrative as a black man. Experimental groups 8–10 read the same consequence frames in combination with the narrative but received a picture depicting the subject of the narrative as a white man. The text of the narrative did not differ across groups. In Table 2, the bolded text indicates the language that differed across the groups.

Table 2.

Exposure Text and Images (Variations in text indicated with bolded text)

|

PUBLIC SAFETY CONSEQUENCE FRAME (Group 2, 5, 8) Word Count: 229 Currently almost half a million Americans are incarcerated for drug crimes, many with lengthy sentences for non-violent offenses. While people should be held accountable for their actions, giving harsh prison sentences for non-violent drug crimes is not an effective way to reduce crime. Research shows that arresting individuals for low-level, non-violent drug crimes has little effect on crime in the community. Studies show that increasing the length of prison sentences for non-violent crimes does not influence whether someone will commit a crime after they are released. Over the past three decades, several policies were passed to increase the severity of punishment for non-violent drug crimes, but these did not result in significant declines in drug-related crime rates. Simply put, unnecessarily long prison sentences for non-violent drug crimes do not make sense if the goal is improving public safety. After a person is released from prison, it is often very difficult to find stable employment, which can make it hard to have enough money to pay for food or a place to live. Challenges around employment, housing and hunger can affect people’s ability to get back on their feet. This is bad for public safety. When individuals are put in a desperate financial situation and are unable to support themselves after being released from prison, they are more likely to turn to crime as a way to make ends meet. | |

|

SOCIAL JUSTICE CONSEQUENCE FRAME (Group 3,6,9) Word Count: 229 Currently almost half a million Americans are incarcerated for drug crimes, many with lengthy sentences for non-violent offenses. While people should be held accountable for their actions, giving harsh prison sentences for non-violent drug crimes disproportionately and unfairly affects vulnerable Americans. Research shows that people of color and those with low-incomes are more often subject to severe prison sentences than other groups. Studies show that even though people of all races report using and selling drugs at similar rates, black Americans are nearly 6.5 times as likely as white Americans to be incarcerated for drug offenses. Low income people are more likely to be unable to afford legal representation and more likely to be sent to prison than higher income people. Simply put, unnecessarily long prison sentences for non-violent drug crimes fall disproportionately on low income and non-white groups and are unjust. After a person is released from prison, it is often very difficult to find stable employment, which can make it hard to have enough money to pay for food or a place to live. Challenges around employment, housing and hunger can affect people’s ability to get back on their feet. This is bad in terms of fairness. When individuals are put in a desperate financial situation and are unable to support themselves after being released from prison, society further increases the hardships already faced by vulnerable individuals. | |

|

IMPACT ON CHILDREN CONSEQUENCE FRAME (Group 4, 7, 10) Word Count: 230 Currently almost half a million Americans are incarcerated for drug crimes, many with lengthy sentences for non-violent offenses. While people should be held accountable for their actions, giving harsh prison sentences for non-violent drug crimes negatively affects children. Research shows that children who have a parent in prison suffer negative consequences while their parent is incarcerated and after their parent is released. Studies show that children with an incarcerated parent are more likely to have poor health and social relationships during and after their parents’ incarceration, compared to their peers without a parent in jail or prison. These social and emotional problems have also been associated with poor school performance and higher dropout rates, and can have long lasting negative affects into adulthood. Simply put, unnecessarily long prison sentences for non-violent drug crimes have major, long term negative consequences on children. After a person is released from prison, it is often very difficult to find stable employment, which can make it hard to have enough money to pay for food or a place to live. Challenges around employment, housing and hunger can affect people’s ability to get back on their feet. This is bad for their children. When individuals are put in a desperate financial situation and are unable to support themselves after being released from prison, they will be unable to provide food or safe housing for their children. | |

|

SYMPATHETIC NARRATIVE (Groups 5,6,7,8,9,10) Word Count: 484 Today David Waller is celebrating his birthday with his son Michael and Michael’s daughter and wife. David feels fortunate that he lives near his son, visits with him often and gets to see his granddaughter grow up. Ten years ago, David’s son was in a very different place. When Michael was 21, he was badly injured at work on a construction site. His doctor treated him with OxyContin, a prescription opioid medication, for the pain. Michael continued to use the pain pill for some time, and David began to notice a change in his son. Michael continued to feel like he needed the medication even after his injury healed. When he ran out of pills, he felt anxious, sweaty and nauseous, and had problems sleeping. When his doctor refused to prescribe more medication, Michael began buying and occasionally selling pills for money. David slowly began to realize that his son had developed an addiction. At one point, David even found out that Michael had used heroin when he ran low on money, because heroin was cheaper than pills. David tried everything he could think of to get help for Michael, including getting him on a waiting list for an addiction treatment program. David was heartbroken when Michael was caught selling pills and convicted of a felony. Michael was subject to a state law requiring a mandatory sentence for his crime and spent the next five years of his life in prison. Since leaving prison, Michael has worked hard to get his life back on track. After he was released, David helped Michael enter a drug treatment program, which has helped Michael stay drug-free. David is incredibly proud of Michael, but it makes him sad to see how his son has been haunted by his felony drug conviction. David watched Michael apply for over 60 jobs without success. Michael was ashamed to have to rely on his father for financial support to help pay his bills, especially because David also lived paycheck to paycheck. Michael finally got a break after David’s friend hired him to work in his store. That was over three years ago, and since then Michael done well in this job, married and become a father. David joined a support group for parents of people who have struggled with drug addiction and being a part of this group has helped him understand that the struggles his son faced getting on his feet were not unique. In fact, many of the stories he hears from the other parents about the challenges their adult children have faced after being released from prison are even worse. Many are unable to find jobs and struggle financially when they return home. David is thankful that his son was able to find a good, stable job to support his family. He knows that many people like Michael who served time for non-violent drug felonies are not so lucky. | |

|

EXPOSURE IMAGE OF NARRATIVE SUBJECT

Included in-line with narrative with caption: Michael Waller | |

(Groups 5,6,7) (Groups 5,6,7)

|

(Groups 8, 9, 10) (Groups 8, 9, 10)

|

The consequence frames focused on the consequences of strict sentencing of individuals with a felony drug conviction and the challenges they face upon release using one of three frames: 1) public safety, 2) social justice, 3) impact on incarcerated individuals’ children. The public safety frame outlined strict sentencing as not deterring future crime and post-release challenges as encouraging of future crime. The social justice frame outlined strict sentencing as disproportionately affecting low-income populations and people of color and post-release challenges as further increasing hardships and disparities. Finally, the impact on children frame outlined strict sentencing as having negative effects on individuals’ children and post-release challenges as resource-limiting for children. All vignettes had similar word counts and used consistent language in depicting of the challenges faced by individuals with felony drug convictions. They differed in the framing of the consequences of these challenges.

A single sympathetic narrative was introduced in experimental groups 5–10 following each of the consequence frames. This sympathetic narrative depicted the hypothetical story of Michael Waller, a man in recovery from opioid use disorder who was recently released from prison following a felony drug conviction. The sympathetic narrative presents Michael as in recovery, because prior research shows that successful depictions of treatment can overcome stigmatizing views towards substance use (Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2016; McGinty et al., 2015). The sympathetic narrative is also written from the perspective of Michael’s father, given a prior message testing experiment showing that presenting narratives that convey the effects of a person’s substance use disorder on their family was effective at increasing support for less punitive policies and decreasing stigma (Bachhuber et al., 2015).

The two images used in sympathetic narrative components of arms 5–7 (image of a black man) and arms 8–10 (images of a white man) were sourced from the Eberhardt Lab Face Database at the Mind, Culture and Society Laboratory at Stanford University. Images from this database, which have been utilized in a number of social science experiments, were rated on age, attractiveness and how stereotypically black or white they appeared on 7-pt Likert scales through online survey respondents (Brosch, Bar-David, & Phelps, 2013; Eberhardt, Davies, Purdie-Vaughns, & Johnson, 2006). The chosen images for this experiment were of a black man and a white man that had identical mean age, attractiveness and stereotypicality ratings according to the Stanford ratings.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests were used to confirm no differences in measured sociodemographic characteristics across experimental groups. Responses to the outcome measures were collapsed from 5-pt Likert scales into dichotomous variables indicating willingness to move next door to an individual with a felony drug conviction, belief in the ability of an individual with a felony drug conviction to rehabilitate and support for each of the four policies of interest.

First, we examined prevalence of the dichotomous stigma and policy support outcomes in the no-exposure control group to understand baseline national attitudes in the U.S. Second, we used ordered logistic regression to test the effect of the message framing elements on the full 5-point scale version of the outcome variables and logistic regression to measure the effect on the dichotomous version of the outcomes. These results were qualitatively similar, so for ease of interpretation, only logistic results are presented. We tested the effects of specific consequence frames by using an indicator variable of exposure to one of the three consequence frames (public safety, social justice, impact on children) with the reference category of no exposure. Predicted percent agreement were generated from these results and postestimation Wald tests were used to assess the differences between the three consequence frames.

Third, we tested the effect of adding the narrative to the consequence frame, or the marginal effect. We first tested the effect of the narrative across all frames, comparing exposure to a narrative combined with any consequence frame to exposure to any consequence frame without a narrative. Then we estimated effects within each consequence frame using a binary independent variable where exposure to a specific consequence frame was the reference compared to exposure to the same consequence frame with the addition of the narrative with either image.

Finally, we examined the difference in the effect of the narrative by the narrative subject’s race. We used an independent variable that was an indicator of exposure to any consequence frame plus a narrative with the black subject, exposure to any consequence frame plus a narrative with the white subject or the reference category of exposure to any consequence frame and no narrative. We then repeated this analysis within specific consequence frames. Wald tests were used to test for differences in the marginal effect of the narrative based on subject’s race. As survey participants were randomly assigned to message exposures, and Pearson Chi-square tests suggested that measured covariates were balanced across groups (Appendix B), we did not include covariates in any regression models.

RESULTS

The demographics characteristics of the sample closely represented the U.S. adult population (Appendix B).

Public Stigma and Policy Support Levels in in No-Exposure Control Group

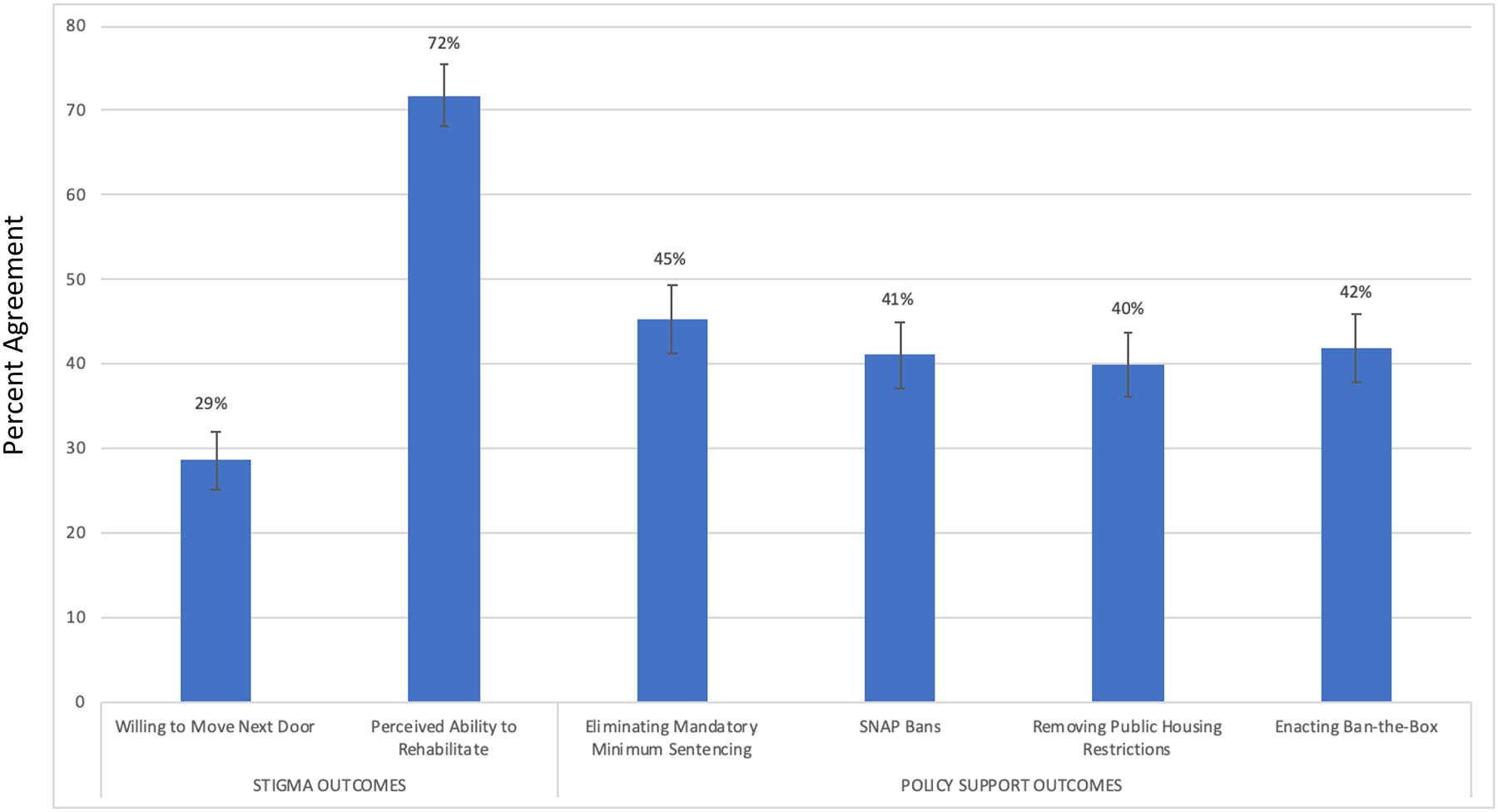

Figure 1 shows the measures of stigma and policy support in the control arm (n=1,070). Only 29% of respondents were willing to move next door to someone with a felony drug conviction, despite the fact that 72% of respondents believed this population were able to return to productive lives in the community following release. Only a minority of the public supported less punitive policies towards individuals with felony drug convictions. Forty-five percent of respondents supported eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing for individuals with felony drug convictions. Forty-one percent of respondents supported removing restrictions to SNAP and 40% supported removing public housing restrictions for this population. Forty-two percent of respondents supported enacting ban-the box-policies applicable to individuals with felony drug convictions.

Figure 1.

Social Stigma and Support for Less Punitive Policies for Individuals with Felony Drug Convictions in No-Exposure Control Group Only (n=1,070)

Note: Error bars represent 95%CI.

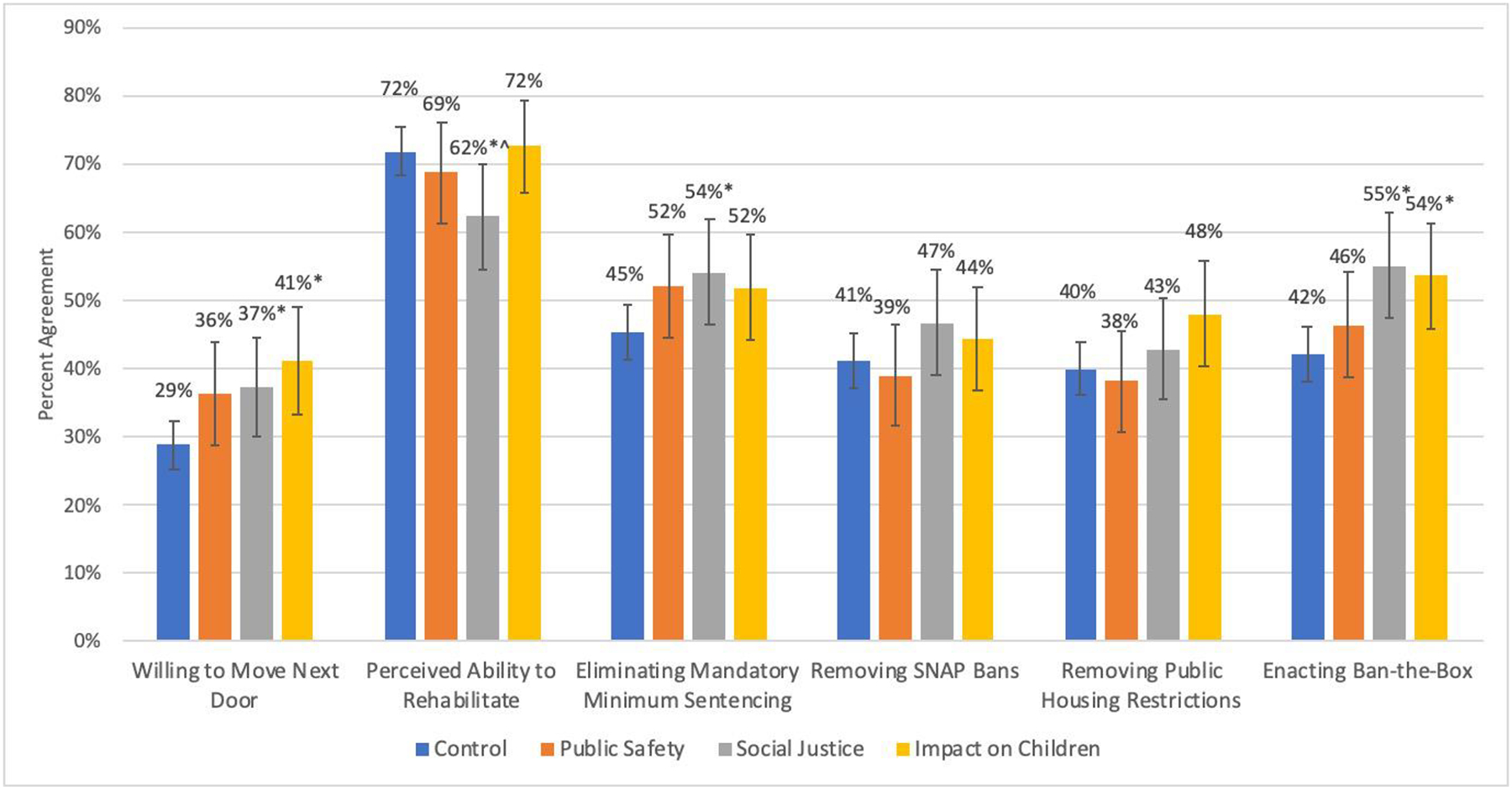

Effect of Consequence Frames

As seen in Figure 2, compared to the control group (29%), participants who read the social justice consequence frame (37%, p=0.04) and the impact on children frame (41%, p<0.01) reported being more willing to live next door to someone convicted of a felony drug crime. The social justice frame was associated with respondents having lower levels of belief in the perceived ability of people with the felony drug convictions to rehabilitate compared to the control group (62% vs 72%, p 0.02). The public safety frame (72%, p 0.44) and the impact on children frame (72%, p 0.86) were not associated with differences in perceived ability to rehabilitate compared to the control group.

Figure 2.

Effects of Consequence Frames Compared to No Exposure Control Group on Social Stigma and Support for Less Punitive Policies

*: p-value<0.05 percent agreement different compared to control group.

Compared to the control group (45%), the social justice frame was associated with greater policy support for eliminating mandatory minimums (54%, p 0.049). There were no statistically significant differences between the effect of the frames’ on support for eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing laws.

Both the social justice (55%, p <0.01) and the impact on children (54%, p <0.01) frames were associated with increased support for enacting ban-the-box policies compared to the control group (42%). There was no effect of the frames on support for removing restrictions to SNAP or public housing.

Effect of Adding Sympathetic Narrative

There was no effect of adding the sympathetic narrative across all consequence frames on attitudes or policy support compared to reading only a consequence frame, as seen in Table 3. When we examine the marginal effect of the sympathetic narrative within specific consequence frames, effects were limited. Within the public safety consequence frame, the addition of the sympathetic narrative increased respondent’s support for removing restrictions to public housing laws compared to just reading the public safety consequence frame without the narrative (49% vs 38%, p 0.02). The sympathetic narrative did not have any marginal effect on any other outcomes within the public safety consequence frame. Within the social justice frame, the addition of the sympathetic narrative increased respondents’ perceptions of perceived ability to rehabilitate (74% vs 62%, p<0.01). The sympathetic narrative did not have any marginal effect on any other outcomes within the social justice frame or any effect on any outcome within the impact on children frame.

Table 3.

Effect of Consequence Frame and Narrative Compared to Exposure to Only Consequence Frame on Social Stigma and Support for Less Punitive Policies

| Predicted Percent Agreement[95% Confidence Intervals] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Frames | Public Safety Frame | Social Justice Frame | Impact on Children Frame | |||||

| No Narrative | Narrative | No Narrative | Narrative | No Narrative | Narrative | No Narrative | Narrative | |

| Willing to Move Next Door | 38 % [34,43] | 41% [38,44] | 36% [28,44] | 44 % [39,49] | 37% [30,44] | 36% [31,41] | 41% [33,49] | 42 % [36,47] |

| Perceived Ability to Rehabilitate | 68 % [63,72] | 71% [69,74] | 69 % [61,76] | 70% [65,75] | 62% [55,70] | 74%* [70,79] | 72% [66,79] | 70% [65,75] |

| Eliminating Mandatory Minimum Sentencing | 53 % [48,57] | 53% [50,56] | 52% [44,60] | 53% [48,59] | 54% [46,62] | 52% [47,58] | 52% [44,60] | 54% [48,59] |

| Removing SNAP Bans | 43 % [39,48] | 48% [45,51] | 39% [32,46] | 46% [41,51] | 47% [39,54] | 49% [44,55] | 44% [37,52] | 48% [42,53] |

| Removing Public Housing Restrictions | 43 % [39,47] | 47% [44,50] | 38% [30,46] | 49%* [44,54] | 43% [35,50] | 48% [42,53] | 48% [40,56] | 45% [40,51] |

| Enacting Ban-the-Box | 52% [47,56] | 51% [48,54] | 46% [39,54] | 51 % [46,57] | 55% [47,63] | 51% [46,57] | 54% [46,61] | 49% [44,55] |

p-value<0.05 Different predicted percentage after exposure to consequence frame and narrative compared to exposure to only consequence frame.

Effect of Adding Sympathetic Narrative: Differences By Race of Narrative Subject

There was no difference in the marginal effect of sympathetic narrative by the narrative subject’s race on any outcomes when examined across all consequence frames, as seen in Table 4. However, when we examine the difference in effect within the social justice frame, some differences arise. Exposure to a white narrative subject elicited greater perceptions of perceived ability to rehabilitate ( 79% vs. 70%, p 0.04) and support for removing restriction to SNAP (55% vs 43%, p 0.03) compared to exposure to narrative with a black subject. There was no difference in effect by narrative subject’s race within the public safety or impact on children frame.

Table 4.

Difference in Effect by Narrative Subject’s Race on Social Stigma and Support for Less Punitive Policies

| Predicted Percent Agreement (95% Confidence Intervals) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Frame | Public Safety Frame | Social Justice Frame | Impact on Children Frame | |||||||||

| No Narrative | Black | White | No Narrative | Black | White | No Narrative | Black | White | No Narrative | Black | White | |

| Willing to Move Next Door | 38% (34, 43) | 42% (38, 46) | 39% (35, 43) | 36% (28, 44) | 44% (36, 51) | 44% (37, 51) | 37% (30, 44) | 35% (28, 42) | 37% (29, 44) | 41% (33, 49) | 47% (39, 55) | 37% (30, 45) |

| Perceived Ability to Rehabilitate | 68% (63, 72) | 69% (65, 73) | 73% (69, 77) | 69% (61, 76) | 67% (59, 74) | 73% (66, 80) | 62% (55, 70) | 70%1 (63, 77) | 79%1,2 (73, 85) | 72% (66, 79) | 72% (66, 79) | 68% (61, 75) |

| Eliminating Mandatory Minimum Sentencing | 53% (48, 57) | 53% (49, 58) | 53% (48, 57) | 52% (44, 60) | 54% (46, 61) | 53% (46, 60) | 54% (46, 62) | 53% (46, 61) | 52% (44, 59) | 52% (44, 60) | 53% (46, 61) | 54% (46, 62) |

| Removing SNAP Bans | 43% (39, 48) | 46% (41, 50) | 49% (45, 54) | 39% (32, 46) | 43% (35, 50) | 49% (42, 56) | 47% (39, 54) | 43% (36, 51) | 55%2 (48, 63) | 44% (37, 52) | 51% (44, 59) | 45% (37, 52) |

| Removing Public Housing Restrictions | 43% (39, 47) | 46% (42, 50) | 49% (44, 53) | 38% (30, 46) | 47% (39, 54) | 52%1 (44, 59) | 43% (35, 50) | 47% (39, 54) | 49% (41, 57) | 48% (40, 56) | 44% (37, 52) | 46% (38, 54) |

| Enacting Ban-the-Box | 52% (47, 56) | 51% (46, 55) | 51% (46, 55) | 46% (39, 54) | 51% (43, 58) | 52% (45, 60) | 55% (47, 63) | 49% (41, 56) | 54% (47, 62) | 54% (46, 61) | 53% (45, 61) | 46% (38, 54) |

p-value<0.05 Exposure to consequence frame with no narrative.

p-value<0.05 Exposure to consequence frame with narrative with black subject.

DISCUSSION

Prior research indicates that individuals with a history of criminal justice involvement or drug use are highly stigmatized, with the public reporting desire for social distance from these populations (Link, Struening, Rahav, Phelan, & Nuttbrock, 1997; Luoma et al., 2007; Pager, 2003; Schnittker & John, 2007; van Olphen et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2017). Our results suggest that individuals with prior felony drug convictions may be experiencing the double stigma of having both criminal justice involvement and potential drug use, reflected in the high levels of desire for social distance in the no-exposure control group. High levels of stigmatizing attitudes may translate into lower support for policies aimed at easing reentry and increasing access to public health services for these populations.

The social justice and impact on children consequence frames were effective at reducing desire for social distance and increasing support such that a majority of respondents supported enacting ban-the-box-policies. Prior research has demonstrated that framing is effective at altering audiences’ judgments of who is responsible for a policy problem, the individual or society at large, which can in turn influence opinions of policy solutions (Entman, 1993; Gollust et al., 2013; Scheufele, 1999). These frames may have been effective by shifting the attribution of responsibility and burden. In the social justice consequence frame, the discussion of the overrepresentation of marginalized populations in the criminal justice system may shift audiences’ perceptions of responsibility for incarceration away from those with a felony drug conviction onto the systematic injustices found within the corrections system. The impact on children consequence frame may have been effective at reducing stigma and increasing support for ban-the-box by reframing the burden of incarceration and reentry away from the parent and onto the child. Future research should examine through what mechanisms these consequence frames affect policy support, such as through eliciting certain emotional responses. These findings can inform future research on ban-the-box policies in the U.S. and broader policy efforts to reduce employment discrimination for criminal justice involved populations. For example, as of October 2017, only half of Canadian provinces have legislation that protects against discrimination based on criminal convictions and several countries in Europe still allow employers to request criminal record certificates as part of employment applications. (Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion, 2018; Pijoan, 2014)

The social justice consequence frame was associated with decreases in the perceived ability of individuals with felony drug convictions to rehabilitate. By highlighting the systemic marginalization of low income and minority communities, this frame may have heightened awareness to the immense challenges that individuals face following incarceration and thereby decreased perceptions of ability to rehabilitate. This finding can inform efforts to reform punitive policies towards populations that are criminal justice involved and/or use drugs. Advocates may highlight the socioeconomic and racial inequities perpetuated by punitive policies as reason for reform. These results suggest that such framing may increase the public’s acceptance of elimination of punitive policies, but it may be at the cost of increase stigmatizing attitudes and the perception that individuals subject to these policies are unable to achieve positive outcomes.

The addition of a sympathetic narrative to the social justice frame attenuated decreases in perceived ability to rehabilitate, which may have been a result of the incorporation of several key features. For example, the narrative presented Michael as in recovery, which has been shown to be effective at reducing stigmatizing views towards substance use (Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2016; McGinty et al., 2015). The narrative was also written from the perspective of Michael’s father, and prior research has shown that presenting narratives that convey the effects of a person’s substance use disorder on their family have been effective at decreasing stigma (Bachhuber et al., 2015). This study’s findings differed from these prior studies in that the narrative did not have a clear marginal effect on increasing policy support for less punitive policies or effects on stigma in other frames. This may be due to the high levels of stigma towards this population, the specific policies we examined, or the specific narrative presented to respondents.

The effect of the sympathetic narrative on improving perceived ability to rehabilitate was greater when the narrative subject was white versus black within the social justice frame. Even within a highly stigmatized population, this study indicates that racism still influences the public’s perceptions of the agency and favorability toward individuals with felony drug convictions. These differences by race may not exist across other outcomes and frames, because overall the narrative had little effect or this population may be so highly stigmatized racial bias may affect respondent attitudes differently.

With the exception of the combination of the public safety consequence frame and sympathetic narrative, none of the exposures were associated with increasing access to SNAP or public housing, the two outcomes that proposed providing government-funded benefits. Perhaps this population is so highly stigmatized the public perceives them as not deservingness of government-funded assistance, except when portrayed as a threat to the public’s safety. These perceptions of deservingness may be related to public attitudes that those who use drugs are responsible for the hardships in their lives. Prior research has shown that the public perceives populations with a substance use disorder as having more control over their conditions compared to populations with a physical health condition and that perceived controllability affects public attitudes towards policy solutions (Corrigan et al., 2000; Corrigan, Watson, Warpinski, & Gracia, 2004; Weiner, Perry, & Magnusson, 1988). Future research on the public’s perceptions of deservingness and its effect on attitudes towards government assistance programs is needed.

Limitations

This study should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, because we wanted to isolate the effects of specific consequence frames and a single narrative, we were unable to use existing media sources. Therefore, this controlled randomized experiment may have limited external generalizability to individuals’ real-world experience. Second, the effect on outcomes was measured immediately after a single exposure. It is unclear how multiple exposures over time would impact the outcomes of interest. Third, the effect of the sympathetic narrative may be unique to the narrative subject presented in this study. We were unable to test differences in effect based on changes to characteristics of the subject other than race due to a limited number of treatment arms. For example, we were unable to test for differences based on the narrative subject’s gender. Fourth, this study focuses on a subset of the criminal justice involved population, those with prior felony drug convictions, and therefore the results may not be generalizable to other criminal justice involved populations. Fifth, the statistically significant findings may be a result of chance and multiple hypothesis testing. Finally, the study is limited to a sample of adults in the U.S.

CONCLUSION

This experiment is aimed at better understanding how message frames influence public attitudes towards a set of policies actively changing in the current policy environment. Employing a social justice or impact on children consequence frame may improve results of stigma reduction campaigns and advocacy efforts towards reducing employment discrimination. However, it also illustrates the need for identification of additional strategies to improve perceptions of these populations’ perceived ability to rehabilitate and deservingness of government assistance. Improving attitudes towards individuals with felony drug convictions may help influence the current policy debates and thereby contribute towards mitigating the harmful effects of mass incarceration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health T32MH109436 (PI: Barry/Stuart). Data was collected by Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences, National Science Foundation Grant 0818839 (PI: Freese/Druckman).

APPENDIX A. OUTCOME MEASURES

Question blocks were randomized and questions within blocks randomized.

BLOCK 1: POLICY SUPPORT

Q1. Some states have mandatory minimum sentencing laws that require minimum prison sentences for people convicted of felony drug crimes. In other states judges are given more leeway to decide prison sentences on a case-by-case basis. Do you favor or oppose eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing laws for people convicted of felony drug crimes?

Strongly Oppose

Oppose

Neither

Favor

Strongly Favor

Q2. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as SNAP or the food stamp program, helps low income families purchase food. In some states people convicted of felony drug crimes are banned from getting SNAP. Do you favor or oppose a law to allow people convicted of felony drug crimes to receive SNAP?

Strongly Oppose

Oppose

Neither

Favor

Strongly Favor

Q3. In some states people convicted of felony drug crimes are banned from housing assistance programs that help with the cost of housing. Do you favor or oppose a law to allow people convicted of felony drug crimes to access housing assistance programs?

Strongly Oppose

Oppose

Neither

Favor

Strongly Favor

Q4. Many employers require that people convicted of felony drug crimes report their prior convictions on job applications. Some states and cities are passing ban-the-box laws that prohibit asking about convictions until later stages of the job application process. Do you favor or oppose ban-the-box laws that prevent employers from asking job applicants about felony drug convictions until later phases of the job application process?

Strongly Oppose

Oppose

Neither

Favor

Strongly Favor

BLOCK 2: SOCIAL STIGMA

Q1. How willing would you be to move next door to someone convicted of a felony drug crime?

Strongly Unwilling

Probably Unwilling

Neither

Probably Willing

Definitely Willing

Q2. Most people convicted of felony drug crimes can return to productive lives in the community with the right kind of help. Do you agree or disagree with this statement?

Strongly Disagree

Disagree

Neither

Agree

Strongly Agree

APPENDIX B. Weighted and Unweighted Characteristics of Sample (n= 3,758)

| Unweighted % | Weighted % | National Comparison1 % | Test of randomization Pearson X2 p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.42 | |||

| 18–24 | 5.4 | 10.5 | 13.1 | |

| 25–34 | 22.4 | 18.6 | 17.5 | |

| 35–44 | 15.2 | 14.6 | 17.5 | |

| 45–64 | 35.8 | 35.1 | 34.7 | |

| 65+ | 21.2 | 21.1 | 17.2 | |

| Female | 50.9 | 51.0 | 50.8 | 0.72 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.15 | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 66.0 | 68.5 | 61.5 | |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 11.2 | 11.2 | 12.3 | |

| Hispanic | 15.2 | 13.0 | 17.6 | |

| Other, Non-Hispanic | 7.6 | 7.3 | 8.6 | |

| Education | 0.92 | |||

| Less than High School | 10.0 | 3.6 | 13.4 | |

| High School | 28.8 | 17.7 | 30.5 | |

| Some College | 29.2 | 44.9 | 45.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 32.0 | 33.9 | 10.6 | |

| Household Income | 0.74 | |||

| <$25,000 | 20.9 | 18.8 | 21.4 | |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 26.2 | 27.0 | 22.5 | |

| $50,001-$74,999 | 18.6 | 19.8 | 17.7 | |

| $75,000 + | 34.2 | 34.4 | 38.5 | |

| Political Party | 0.38 | |||

| Republican | 24.9 | 24.5 | 23.5 | |

| Democrat | 31.4 | 34.1 | 32.5 | |

| Independent/Other | 43.7 | 41.3 | 43.3 | |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 17.5 | 14.7 | 17.2 | 0.34 |

| Midwest | 20.6 | 26.8 | 20.9 | |

| South | 38.1 | 34.3 | 38.1 | |

| West | 23.8 | 24.1 | 23.8 | |

| Employment | ||||

| Working | 58.4 | 61.4 | 59.3 | 0.11 |

| Not Working-Looking | 7.2 | 5.3 | 4.1 | |

| Not Working-Other | 34.4 | 33.3 | 36.6 |

U.S. Census Bureau; 2017 American Community Survey; 2012 American National Election Survey

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

REFERENCES

- Agan A, & Starr S (2018). Ban the Box, Criminal Records, and Racial Discrimination: A Field Experiment*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(1), 191–235. 10.1093/qje/qjx028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern J, Stuber J, & Galea S (2007). Stigma, discrimination and the health of illicit drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88(2), 188–196. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum B (2015, March 1). Out of Trouble, Out of Work. The New York Times, p. Pg. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Avery B (2019, April 19). Ban the Box: U.S. Cities, Counties, and States Adopt Fair Hiring Policies Retrieved May 28, 2019, from National Employment Law Project website: https://nelp.org/publication/ban-the-box-fair-chance-hiring-state-and-local-guide/

- Bachhuber MA, McGinty EE, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Niederdeppe J, & Barry CL (2015). Messaging to Increase Public Support for Naloxone Distribution Policies in the United States: Results from a Randomized Survey Experiment. PloS One, 10(7), e0130050 10.1371/journal.pone.0130050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, McGinty EE, Pescosolido BA, & Goldman HH (2014). Stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy: Public views about drug addiction and mental illness. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 65(10), 1269–1272. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, Webster DW, Stone E, Crifasi CK, Vernick JS, & McGinty EE (2018). Public Support for Gun Violence Prevention Policies Among Gun Owners and Non–Gun Owners in 2017. American Journal of Public Health, 108(7), 878–881. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo LD, & Johnson D (2004). A Taste for Punishment: Black and White Americans’ Views on the Death Penalty and the War on Drugs. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 1(1), 151–180. 10.1017/S1742058X04040081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Born M (2018, June 20). In Some States, Drug Felons Still Face Lifetime Ban On SNAP Benefits. Retrieved April 18, 2019, from NPR.org website: https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2018/06/20/621391895/in-some-states-drug-felons-still-face-lifetime-ban-on-snap-benefits

- Brosch T, Bar-David E, & Phelps EA (2013). Implicit Race Bias Decreases the Similarity of Neural Representations of Black and White Faces. Psychological Science, 24(2). 10.1177/0956797612451465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler R, Nyhan B, Montgomery JM, & Torres M (2018). Revisiting white backlash: Does race affect death penalty opinion? Research & Politics, 5(1), 2053168017751250 10.1177/2053168017751250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bye L, Ghirardelli A, & Fontes A (2016). Promoting Health Equity And Population Health: How Americans’ Views Differ. Health Affairs, 35(11), 1982–1990. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion. (2018). Overview of Human Rights Codes by Province and Territory in Canada. Retrieved from https://ccdi.ca/media/1414/20171102-publications-overview-of-hr-codes-by-province-final-en.pdf

- Chong D, & Druckman JN (2007). Framing Theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 10(1), 103–126. 10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, Wasowski, kyle U, Campion J, Mathisen J, … kubiak MA (2000). Stigmatizing attributions about mental illness. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(1), 91–102. Retrieved from asn. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Warpinski AC, & Gracia G (2004). Stigmatizing attitudes about mental illness and allocation of resources to mental health services. Community Mental Health Journal, 40(4), 297–307. 10.1023/b:comh.0000035226.19939.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Garlington S, & Schottenfeld LS (2013). Alcohol, Drug, and Criminal History Restrictions in Public Housing. Cityscape: A Journal of Polciy Development and Research, 15(3), 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis J. Michael. (2017). Technical Overview of the AmeriSpeak Panel NORC’s Probability-Based Research Panel. Retrieved from NORC at the University of Chicago website: https://d3qi0qp55mx5f5.cloudfront.net/amerispeak/i/research/AmeriSpeak_Technical_Overview_2017_05_09.pdf?mtime=1494625611https://d3qi0qp55mx5f5.cloudfront.net/amerispeak/i/research/AmeriSpeak_Technical_Overview_2017_05_09.pdf?mtime=1494625611https://d3qi0qp55mx5f5.cloudfront.net/amerispeak/i/research/AmeriSpeak_Technical_Overview_2017_05_09.pdf?mtime=1494625611

- Doleac J, & Hansen B (2019). The unintended consequences of “ban the box”’: Statistical discrimination and employment outcomes when criminal histories are hidden.” Journal of Labor Economics, 705880. 10.1086/705880 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt JL, Davies PG, Purdie-Vaughns VJ, & Johnson SL (2006). Looking Deathworthy: Perceived Stereotypicality of Black Defendants Predicts Capital-Sentencing Outcomes. Psychological Science, 17(5), 383–386. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entman RM (1993). Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce RJ, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Schomerus G, & Evans-Lacko SE (2015). The downside of tobacco control? Smoking and self-stigma: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 145, 26–34. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust SE, Lantz PM, & Ubel PA (2009). The polarizing effect of news media messages about the social determinants of health. American Journal of Public Health, 99(12), 2160–2167. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust SE, Niederdeppe J, & Barry CL (2013). Framing the Consequences of Childhood Obesity to Increase Public Support for Obesity Prevention Policy. American Journal of Public Health, 103(11), e96–e102. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb A (2017). The Effect of Message Frames on Public Attitudes Toward Criminal Justice Reform for Nonviolent Offenses. Crime & Delinquency, 63(5), 636–656. 10.1177/0011128716687758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross K (2008). Framing Persuasive Appeals: Episodic and Thematic Framing, Emotional Response, and Policy Opinion. Political Psychology, 29(2), 169–192. 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00622.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gubits D, Shinn M, Bell S, Wood M, Dastrup S, Solari CD, & Brown SR (2015). Family Options Study: Short-Term Impacts of Housing and Services Interventions for Homeless Families. US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. [Google Scholar]

- Haberman M, & Karni A (2019, April 2). Trump Celebrates Criminal Justice Overhaul Amid Doubts It Will Be Fully Funded. The New York Times; Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/01/us/politics/first-step-act-donald-trump.html [Google Scholar]

- Hetey RC, & Eberhardt JL (2014). Racial Disparities in Incarceration Increase Acceptance of Punitive Policies. Psychological Science, 25(10), 1949–1954. 10.1177/0956797614540307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood M, Brener L, Frankland A, & Treloar C (2010). Assessing community support for harm reduction services: Comparing two measures: Community support for harm reduction. Drug and Alcohol Review, 29(4), 385–391. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00151.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S (1990). Framing responsibility for political issues: The case of poverty. Political Behavior, 12(1), 19–40. 10.1007/BF00992330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S (1996). Framing Responsibility for Political Issues. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 546(1), 59–70. 10.1177/0002716296546001006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, & Tversky A (1984). Choices, values, and frames. American Psychologist, 39(4), 341–350. 10.1037/0003-066X.39.4.341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JC, Elafros MA, Murray SM, Mitchell EMH, Augustinavicius JL, Causevic S, & Baral SD (2019). A scoping review of health-related stigma outcomes for high-burden diseases in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Medicine, 17 10.1186/s12916-019-1250-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, Gollust SE, Ensminger ME, Chisolm MS, & McGinty EE (2017). Social Stigma Toward Persons With Prescription Opioid Use Disorder: Associations With Public Support for Punitive and Public Health–Oriented Policies. Psychiatric Services, 68(5), 462–469. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy-Hendricks A, Levin J, Stone E, McGinty EE, Gollust SE, & Barry CL (2019). News Media Reporting On Medication Treatment For Opioid Use Disorder Amid The Opioid Epidemic. Health Affairs, 38(4), 643–651. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy-Hendricks A, McGinty EE, & Barry CL (2016). Effects of Competing Narratives on Public Perceptions of Opioid Pain Reliever Addiction During Pregnancy. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 41(5), 873–916. 10.1215/03616878-3632230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körner H, & Treloar C (2004). Needle and syringe programmes in the local media: “Needle anger” versus “effective education in the community.” International Journal of Drug Policy, 15(1), 46–55. 10.1016/S0955-3959(03)00089-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, & Nuttbrock L (1997). On stigma and its consequences: Evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(2), 177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez G (2017, September 5). The new war on drugs. Retrieved January 19, 2018, from Vox website: https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/9/5/16135848/drug-war-opioid-epidemic

- Luoma JB, Twohig MP, Waltz T, Hayes SC, Roget N, Padilla M, & Fisher G (2007). An investigation of stigma in individuals receiving treatment for substance abuse. Addictive Behaviors, 32(7), 1331–1346. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Goldman HH, Pescosolido B, & Barry CL (2015). Portraying mental illness and drug addiction as treatable health conditions: Effects of a randomized experiment on stigma and discrimination. Social Science & Medicine, 126, 73–85. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Niederdeppe J, Heley K, & Barry CL (2017). Public perceptions of arguments supporting and opposing recreational marijuana legalization. Preventive Medicine, 99, 80–86. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Webster DW, & Barry CL (2013). Effects of news media messages about mass shootings on attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness and public support for gun control policies. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(5), 494–501. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13010014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. (2014). The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog/18613

- Niederdeppe J, Heley K, & Barry CL (2015). Inoculation and Narrative Strategies in Competitive Framing of Three Health Policy Issues: Inoculation and Narrative in Competitive Framing. Journal of Communication, 65(5), 838–862. 10.1111/jcom.12162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pager D (2003). The Mark of a Criminal Record. American Journal of Sociology, 108(5), 937–975. 10.1086/374403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pager D, Western B, & Sugie N (2009). Sequencing Disadvantage: Barriers to Employment Facing Young Black and White Men with Criminal Records. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 623(1), 195–213. 10.1177/0002716208330793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peffley M, & Hurwitz J (2007). Persuasion and Resistance: Race and the Death Penalty in America. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 996–1012. 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00293.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, Medina TR, Phelan JC, & Link BG (2010). “A Disease Like Any Other”? A Decade of Change in Public Reactions to Schizophrenia, Depression, and Alcohol Dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(11), 1321–1330. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijoan EL (2014). Legal protections against criminal background checks in Europe. Punishment & Society, 16(1), 50–73. 10.1177/1462474513506031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, & Heuer CA (2009). The Stigma of Obesity: A Review and Update. Obesity, 17(5), 941–964. 10.1038/oby.2008.636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheufele D (1999). Framing as a theory of media effects. Journal of Communication, 49(1), 103–122. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1999.tb02784.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, & Ingram H (1993). Social Construction of Target Populations: Implications for Politics and Policy. American Political Science Review, 87(02), 334–347. 10.2307/2939044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J, & John A (2007). Enduring Stigma: The Long-Term Effects of Incarceration on Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(2), 115–130. 10.1177/002214650704800202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar C, & Fraser S (2007). Public opinion on needle and syringe programmes: Avoiding assumptions for policy and practice. Drug and Alcohol Review, 26(4), 355–361. 10.1080/09595230701373867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Agriculture. (2018). State Options Reports. Retrieved from https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/waivers/state-options-report

- US Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2015, November 2). Guidance for Public Housing Agencies (PHAs) and Owners of Federally-Assisted Housing on Excluding the Use of Arrest Records in Housing Decisions. Retrieved from U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Public and Indian Housing; website: https://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/documents/huddoc?id=PIH2015-19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- US. Department of Justice. (2018). Prisoners in 2016 (No. NCJ251149) Retrieved from US. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; website: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p16.pdf [Google Scholar]

- van Olphen J, Eliason MJ, Freudenberg N, & Barnes M (2009). Nowhere to go: How stigma limits the options of female drug users after release from jail. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 4, 10 10.1186/1747-597X-4-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang EA, Zhu GA, Evans L, Carroll-Scott A, Desai R, & Fiellin LE (2013). A pilot study examining food insecurity and HIV risk behaviors among individuals recently released from prison. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 25(2), 112–123. 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.2.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B, Perry RP, & Magnusson J (1988). An attributional analysis of reactions to stigmas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(5), 738–748. 10.1037//0022-3514.55.5.738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildeman C, & Wang EA (2017). Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1464–1474. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30259-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak KH (2019). The Effect of Exposure to Racialized Cues on White and Black Public Support for Justice Reinvestment. Justice Quarterly, 0(0), 1–29. 10.1080/07418825.2018.1486448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Wong LY, Grivel MM, & Hasin DS (2017). Stigma and substance use disorders: An international phenomenon. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(5), 378–388. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]