Summary

The aim of this study was to assess whether clinical work constitutes a risk factor for Helicobacter pylori infection among employees in hospitals. The prevalence of H. pylori infection was analysed in 249 individuals employed in a university teaching hospital according to three categories of hospital workers: (A) personnel from gastrointestinal endoscopy units (N=92); (B) personnel from other hospital units with direct patient contact (N=105); and (C) staff from laboratories and other units with no direct patient contact (N=52). Stool samples from each subject were examined with a validated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the presence of H. pylori antigens. A questionnaire inquiring about sociodemographic and occupational characteristics was completed by each participant. The prevalence of H. pylori infection was 37.0% in group A, 35.2% in group B and 19.2% in group C (P<0.05). Among the different healthcare categories, nurses had a significant higher prevalence of H. pylori infection (P<0.01). No significant association was found between the length of employment or exposure to oral and faecal secretions, and H. pylori infection. Hospital work involving direct patient contact seems to constitute a major risk factor for H. pylori infection compared with hospital work not involving direct patient contact.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Healthcare workers, Occupational infection

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infection probably represents the most common bacterial infection of the human species with a prevalence of 25–50% in developed countries and up to 90% in developing countries.1, 2 A wide body of evidence now indicates that H. pylori is the major aetiological agent of chronic active gastritis,3 and gastric and duodenal ulcers,4 and represents a major risk factor for the development of gastric cancer.5 H. pylori is almost always acquired in childhood and, if untreated, infection is usually lifelong. The only consistent source of H. pylori is the gastric mucosa of human beings. An environmental source of infection has not been identified. Person-to-person spread therefore seems to be the most likely mode of transmission.2 Evidence that supports person-to-person transmission includes the clustering of H. pylori infection in families,6, 7, 8 in institutions for the mentally handicapped9, 10 and in submarine crews.11 As well as in the human stomach, viable H. pylori cells have been detected in faeces and oral secretions.12, 13 Therefore, possible routes of person-to-person transmission are gastric to oral, faecal to oral, or oral to oral.2, 14, 15 Healthcare workers who come into contact with patients and contaminated secretions could be at increased risk of infection by H. pylori. The majority of studies on the risk of infection for healthcare workers have focused on endoscopists and endoscopy room staff. These studies, mainly performed by serological diagnosis, have yielded conflicting results about the rate of H. pylori infection among professionals performing gastroendoscopic procedures. Some studies have not found a statistically significant difference in the infection rates compared with controls,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 while others have.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 Consequently, a consensus has not been reached regarding the occupational risk for acquiring H. pylori infection. In these studies, different groups of subjects have been used as controls: blood donors;23 healthy non-medical professionals;21, 24, 25 and non-endoscopy medical personnel.18, 22

The H. pylori infection rate among patients undergoing endoscopy for upper gastrointestinal symptoms in Italy is as high as 71.3%;28 therefore, medical and nursing staff involved in endoscopic procedures could have a high risk of occupational exposure.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether different staff groups of healthcare workers, either with or without direct patient contact, are at equal risk of acquiring H. pylori infection. For epidemiological studies of H. pylori, the non-invasive stool antigen test (HpSA) is a useful and appropriate diagnostic method that is both practical and highly sensitive. Therefore, we used the HpSA test that, in contrast to serology, reflects the current status of tested individuals with regard to the presence or absence of H. pylori infection.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

The target population consisted of the personnel working at the Umberto I Hospital, a university teaching hospital located in Rome, Italy. From January to July 2001, 249 subjects underwent the HpSA in order to assess H. pylori infection status. Individuals who had taken antimicrobial and antacid drugs during the three weeks preceding the test were excluded from the study. Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. A questionnaire was completed by participants before collection of the faecal specimen. The questionnaire included the following items: age; sex; profession; department of employment; length of employment; exposure to gastrointestinal or oral secretions; history of upper gastrointestinal pain, dyspepsia or ulcer disease; and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or medication for any gastrointestinal complaints, such as antacids or histamine-2-blocking agents. For endoscopists, additional items were: average number of gastroendoscopic examinations performed or assisted per week; and use of infection prevention procedures including routine wearing of gloves and mask during endoscopic procedures.

Enzyme immunoassay

Stool specimens were obtained from each participant. The specimens were stored at −70 °C. H. pylori stool antigen was measured using an antigen enzyme immunoassay (EIA; Premier Platinum HpSA; Meridian Diagnostics, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). The test using polyclonal antibodies to H. pylori was performed as indicated by the manufacturer, and the results were read by spectrophotometry. Specimens with absorbance values (A 450/630) of =0.120 were positive, those with values of =0.100 and <0.120 were equivocal, and those with values of <0.100 were negative. The EIA has a reported sensitivity of 96.1%, a specificity of 95.7% and showed 95.9% correlation with H. pylori infection (data provided by Meridian Diagnostics, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to tabulate the data and make comparisons. All tests and P values were two-tailed. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The outcome variable was the infection with H. pylori. Multi-variate analysis was performed using logistic regression to analyse the independent effect of each variable on the outcome and possible interaction.

Results

Study population and H. pylori infection

Two hundred and forty-nine subjects (mean age 43.0 years, SD=9.2 years, age range 24–69 years), all working in the hospital, were included in the study population and divided into three groups:

-

(A)

healthcare personnel (i.e. physicians, nurses) actively working in an endoscopy unit (N=92, mean age 42.4 years, SD=9.2 years, age range 24–65 years);

-

(B)

healthcare personnel (i.e. physicians, nurses) in contact with patients, but not working in an endoscopy unit (N=105, mean age 41.6 years, SD=8.8 years, age range 24–60 years); and

-

(C)

healthcare personnel working in laboratories (i.e. physicians, biologists, chemists, technicians) and other hospital units with no patient contact (N=52, mean age 46.7 years, SD=9.3 years, age range 27–69 years).

H. pylori prevalence in the three subgroups by sociodemographic characteristics is shown in Table I . Among the 249 subjects, 81 (32.5%) tested positive for H. pylori. Logistic regression analysis showed that crude H. pylori prevalence was significantly higher in both groups A (OR=2.46; 95% CI 1.10–5.53; P=0.03) and B (OR=2.29; 95% CI 1.03–5.07; P=0.04) compared with group C (Table II ). These odds ratios do not change substantially when adjusted for sex, age and education level.

Table I.

Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in the study population by sociodemographic characteristics

| Gastrointestinal endoscopy personnel (N=92) |

General medical staff (N=105) |

Staff with no patient contact (N=52) |

Total (N=249) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive/tested (%) | ||||

| All | 34/92 (37.0) | 37/105 (35.2) | 10/52 (19.2) | 81/249 (32.5) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 12/35 (34.3) | 14/31a (45.2) | 3/19 (15.8) | 29/85 (34.1) |

| Female | 22/57 (38.6) | 23/73a (31.5) | 7/33 (21.2) | 52/163 (31.9) |

| Age | ||||

| <40 | 6/32 (18.8) | 13/40b (32.5) | 2/12a (16.7) | 21/84 (25.0) |

| ≥40 | 28/60 (46.7) | 22/60b (36.7) | 7/39a (17.9) | 57/159 (35.8) |

| Education (years) | ||||

| >13 | 16/47 (34.0) | 5/32 (15.6) | 4/23 (17.4) | 25/101 (24.7) |

| 8–13 | 12/34 (35.3) | 20/45 (44.4) | 4/20 (20.0) | 36/100 (36.0) |

| ≤8 | 6/11 (54.5) | 12/28 (42.9) | 2/9 (22.2) | 20/48 (41.7) |

Missing data, N=1.

Missing data, N=5.

Table II.

Odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for Helicobacter pylori infection according to personnel activity, age, education and profession

| Univariate analysis |

Multi-variate analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Personnel activity | ||||

| No patient contact (C) | 1 | 1 | ||

| General medical staff (B) | 2.29 (1.03–5.07) | 0.04 | 2.57 (1.10–6.01) | 0.03 |

| Endoscopy personnel (A) | 2.46 (1.10–5.53) | 0.03 | 3.08 (1.32–7.22) | 0.01 |

| Age (years)a | ||||

| <40 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥40 | 1.68 (0.93–3.03) | 0.04 | 1.75 (0.93–3.28) | 0.08 |

| Education | ||||

| >13 years | 1 | 1 | ||

| 8–13 years | 1.71 (0.93–3.14) | 0.08 | 1.72 (0.91–3.24) | 0.09 |

| ≤8 years | 2.17 (1.05–4.51) | 0.04 | 2.00 (0.91–4.42) | 0.08 |

Missing data, N=6.

As shown in Table I, there was no sex difference in H. pylori prevalence. Although not statistically significant, H. pylori prevalence in the overall population increased with age (infected people: mean age 44.0 years, SD 8.4 years vs uninfected people: mean age 42.5 years, SD 9.6 years). In the endoscopy units, physicians and nursing personnel less than 40 years of age had a lower prevalence of H. pylori infection (18.8% vs 46.7%, P<0.01). Therefore, concentrating on endoscopy status and age, when adjusted for exposure to endoscopy, workers aged ≥40 years had a significantly higher risk of infection (OR=1.86; 95% CI 1.02–3.40; P=0.04). When adjusted for age, the H. pylori infection risk in groups A and B was higher than that in group C (OR=2.96; 95% CI 1.27–6.89; P=0.01 vs OR=2.80; 95% CI 1.21–6.50; P=0.02).

Education level was used as a surrogate measure of socio-economic status as reported previously.28, 29 An inverse relationship between educational attainment and infection in the overall population was seen in univariate analysis, showing more risk for healthcare personnel with ≤8 years of education compared with staff with a university education (Table II). As reported in Table I, in the subgroup of general medical staff, personnel with a university education showed a significantly lower prevalence of infection (P<0.01) compared with personnel with a lower education level. The level of education was not related to H. pylori infection in staff with no patient contact.

Prevalence of H. pylori by occupational characteristics

The prevalence of H. pylori infection by professional category is reported in Table III . A logistic regression univariate analysis was carried out in order to evaluate H. pylori infection in relation to occupational activity. The results showed that H. pylori prevalence was significantly higher among nurses (OR=4.00; 95% CI 1.56–10.25; P<0.01), doctors (OR=2.19; 95% CI 0.80–5.95; P=0.12) and others (OR=2.92; 95% CI 0.57–14.95; P=0.20) compared with laboratory staff. After adjustment for potential confounding factors, such as age and years of education, nurses maintained a higher risk of infection by H. pylori (OR=4.30; 95% CI 1.32–13.94; P=0.01) by multiple logistic regression analysis. There was no significant difference in prevalence according to length of employment in the overall population or in the three subgroups. Also, exposure to oral and faecal secretions was not associated with infection status (Table III).

Table III.

Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in the study population by occupational characteristics

| Gastrointestinal endoscopy personnel (N=92) |

General medical staff (N=105) |

Staff with no patient contact (N=52) |

Total (N=249) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive/tested (%) | ||||

| Profession | ||||

| Physician | 16/47 (34.0) | 5/30a (16.7) | – | 21/77 (27.3) |

| Nurse | 18/45 (40.0) | 30/73a (41.1) | – | 48/118 (40.7) |

| Laboratory personnel | – | – | 6/41a (14.6) | 6/41 (14.6) |

| Otherb | – | – | 3/9a (33.3) | 3/9 (33.3) |

| Employment | ||||

| ≤10 | 10/35 (28.6) | 9/28c (32.1) | 3/9d (33.3) | 22/72 (30.6) |

| 11–20 | 10/20 (50.0) | 13/43c (30.2) | 3/18d (16.7) | 26/81 (32.1) |

| >20 | 14/37 (37.8) | 14/41c (34.1) | 3/24d (12.5) | 31/92 (33.7) |

| Exposure to oral secretions | ||||

| Yes | 29/75a (38.7) | 19/55e (34.5) | 1/18d (5.6) | 49/148 (33.1) |

| No | 4/15a (26.7) | 17/46e (37.0) | 8/33d (24.2) | 29/94 (30.8) |

| Exposure to faecal secretions | ||||

| Yes | 27/70d (38.6) | 16/43c (37.2) | 2/19d (10.5) | 45/132 (34.1) |

| No | 7/21d (33.3) | 20/59c (33.9) | 7/32d (21.9) | 34/112 (30.4) |

Missing data, N=2.

Auxiliary personnel, secretarial staff.

Missing data, N=3.

Missing data, N=1.

Missing data, N=4.

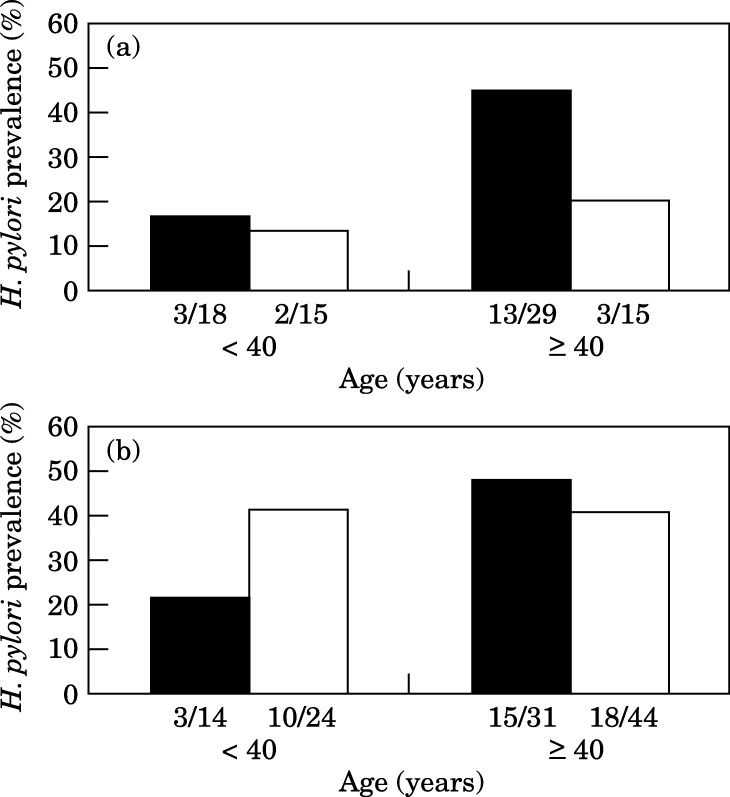

Figure 1 presents the H. pylori prevalence in endoscopy personnel and general medical staff by age group (<40 vs ≥40 years old). Both physicians and nurses working in an endoscopy unit showed an age-related difference in the prevalence of H. pylori infection. Physicians less than 40 years of age had significantly lower prevalence than older subjects (16.7% vs 44.8%, P<0.05), whereas the difference did not reach statistical significance among nurses (21.4% vs 48.4%, P=0.09). In contrast, the rate of infection in general medical staff did not show any significant difference with age.

Figure 1.

Helicobacter pylori prevalence in gastrointestinal endoscopy personnel (solid bars) and general medical staff (open bars) by age groups. (a) Physicians, (b) nurses.

Although not statistically significant, a difference between endoscopist and non-endoscopist physicians aged ≥40 years was observed (44.8% vs 20.0%, P=0.1), whereas younger physicians of the two groups showed a similar prevalence of H. pylori infection (16.7% vs 13.3%). On the contrary, endoscopy nurses aged ≥40 years did not differ in their H. pylori prevalence from general nurses of the same age, whereas surprisingly, among nurses <40 years, the prevalence was higher among general nurses.

For endoscopists, the number of endoscopies performed per week and the time working in the endoscopy unit were considered to be possible risk factors. In both cases, there was no significant association (Table IV ). Regarding infection prevention, all endoscopy personnel wore gloves during every endoscopic procedure, and 66.6% of the personnel used a mask. Among physicians, 54.3% always wore a mask during endoscopic practice, and among nursing personnel, 79.5% used a mask during endoscopy and during the cleaning of endoscopes. No association between the use of a mask and the prevalence of H. pylori infection was observed.

Table IV.

Helicobacter pylori status in endoscopy personnel in relation to the frequency of gastroscopies performed per week, to the duration of gastroscopy practice and to infection prevention measures

| Physicians |

Nurses |

Total personnel |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive/tested (%) | |||

| UGI endoscopies per week (N) | |||

| ≤30 | 6/20 (30.0) | 5/11 (45.5) | 11/31 (35.5) |

| 31–60 | 5/16 (31.3) | 6/13 (46.1) | 11/29 (37.9) |

| >60 | 5/10 (50.0) | 7/21 (33.3) | 12/31 (38.7) |

| Total | 16/46a (34.8) | 18/45 (40.0) | 34/91 (37.4) |

| Duration of work in endoscopy (years) | |||

| ≤10 | 7/24 (29.2) | 3/11 (27.3) | 10/35 (28.6) |

| 11–20 | 4/8 (50.0) | 6/12 (50.0) | 10/20 (50.0) |

| >20 | 5/15 (33.3) | 9/22 (40.9) | 14/37 (37.8) |

| Total | 16/46 (34.8) | 18/45 (40.0) | 34/92 (37.0) |

| Infection prevention | |||

| Use of a maskb | |||

| Yes | 8/25 (32.0) | 14/35 (40.0) | 22/60 (36.7) |

| No | 8/21 (38.1) | 3/9 (33.3) | 11/30 (36.7) |

UGI, upper gastrointestinal.

Missing data, N=1.

Missing data, N=2.

Previous ulcer history and gastrointestinal symptoms

A history of gastritis and/or H. pylori infection were more frequent in endoscopy (26% and 18%) and general medical personnel (23% and 11%) compared with staff with no patient contact (17% and 2%). Thirteen endoscopy personnel with a previous history of gastritis and/or H. pylori infection had received specific antimicrobial therapy; however, three of them were infected with H. pylori (23%). In the general medical staff group, 13 healthcare workers reported previous therapy for H. pylori infection, five of whom were positive for H. pylori faecal antigen (38%). None of the six healthcare workers in the group with no patient contact that were treated for H. pylori infection were infected.

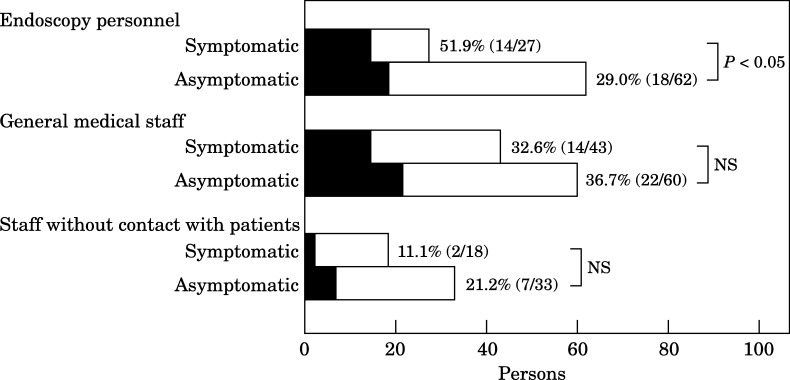

Gastrointestinal symptoms were noted by 88 workers: 30% of endoscopy personnel, 42% of general medical staff and 35% of personnel with no patient contact. The most commonly reported gastrointestinal symptoms were abdominal pain in 52 subjects, dyspepsia in 38 subjects and nausea in 17 subjects. Twenty-six healthcare workers reported more than one gastrointestinal symptom. A statistically significant difference in the prevalence of infection was found between symptomatic and asymptomatic endoscopy personnel, whereas in general medical staff and in personnel with no patient contact, the difference was not significant (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in personnel with or without gastrointestinal symptoms. Solid bars, positive H. pylori stool antigen test (HpSA); open bars, negative HpSA.

Discussion

Healthcare workers who are routinely exposed to patients and contaminated secretions are at increased risk of infection with parenteral viruses30 and other micro-organisms31 including emerging infectious diseases, as the recent severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak confirmed.32

Although a high H. pylori infection rate has been reported frequently in gastrointestinal endoscopy personnel, very few studies have been carried out on the prevalence of infection in different groups of hospital employees.29, 33, 34 No data are available on the H. pylori infection rate of healthcare workers exposed to H. pylori-contaminated secretions without patient contact, such as laboratory staff, in comparison with medical personnel (physicians and nurses) who had contact with patients.

Our study shows a significantly lower H. pylori infection prevalence in laboratory personnel compared with other hospital professional categories despite the fact that many of the laboratory personnel worked in a clinical microbiology laboratory where H. pylori was cultured, and most of the laboratory workers analyse faeces and oral samples in which the micro-organism may be present. Laboratory workers, when handling potentially infectious samples, are aware of the need to use universal precautions.

Our results demonstrate that the prevalence of H. pylori infection is high and similar in gastrointestinal endoscopy personnel and other medical staff with direct patient contact, underlining the importance of contact with patients rather than the endoscopy activity itself as a risk factor for the acquisition of infection. Similar conclusions were reported by Braden et al. 20 who found high H. pylori infection rates in physicians and nurses with contact to patients in general but not additionally in personnel with explicit exposure to gastric secretions during endoscopy. Among healthcare workers with a previous history of recovered H. pylori infection, we observed a high prevalence of re-infection in the endoscopy and general medical staff groups. No infection was observed in H. pylori-treated workers with no patient contact, suggesting a higher chance of re-infection in personnel with direct patient contact.

Multi-variate logistic regression analysis showed that in our local community, H. pylori infection prevalence was highest in nurses. An increased infection rate in nurses has also been reported by Gasbarrini et al. 29 but only following univariate analysis. We observed similar prevalence of infection in nurses working in an endoscopy unit or other clinical departments. Therefore, strict and continuous contact with patients seems to be a risk factor for H. pylori infection because the infected patients may release and spread the micro-organism from saliva, stool and vomitus. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that emesis can be a potent mechanism for discharging millions of H. pylori cells into the environment, and positive H. pylori cultures have also been obtained from air sampled during vomiting.13 Our results suggest that professional category exposure involving direct patient contact rather than educational attainment of healthcare workers can constitute a risk factor for H. pylori infection. In agreement, the rate of infection in laboratory personnel (contrarily to general medical staff) was low and was not influenced by educational level (technicians, 10.5%; graduates, 18.2%).

Among endoscopy workers, older personnel (≥40 years) showed a significantly higher H. pylori infection rate compared with younger personnel. On the contrary, in general medical staff and staff with no patient contact, the H. pylori infection incidence was not influenced by age. Although the study design did not allow this aspect to be investigated specifically, it may be hypothesized that since the H. pylori identification by Warren and Marshall35 in 1984, endoscopy personnel have probably acquired safer working habits and thus younger workers may have had a lower risk of infection. Moreover, the high prevalence in older endoscopy staff suggests that the period in which the exposure during endoscopy occurred could have enhanced acquisitional risk. The high prevalence of infection in general nurses of the two age groups (<40 and ≥40 years) suggests that infection control measures adopted in non-endoscopy departments are probably not as efficacious towards H. pylori, a micro-organism that colonizes the stomach for years or decades causing asymptomatic infections in most cases. Our results indicate that 30% of asymptomatic healthcare personnel are infected by H. pylori, and 61% of infected workers have never had symptoms related to the gastrointestinal tract.

In conclusion, the results of our study indicate that hospital work involving direct patient contact is associated with H. pylori infection, and suggest that safe working habits used by laboratory personnel or endoscopy staff, due to awareness of the existence of H. pylori, could prevent transmission of infection. The high infection rate observed in nurses suggests an increased risk of occupational exposure and calls for more strict precautionary guidelines to reduce the transmission of H. pylori to healthcare staff.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant (n. 922) from Ministero del Lavoro e della Previdenza Sociale (Italy). We appreciate the contribution of all those who generously participated in this study.

References

- 1.EUROGAST Study Group Epidemiology of and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection among 3194 asymptomatic subjects in 17 populations. Gut. 1993;34:1672–1676. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.12.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodman C.K., Correa P. The transmission of Helicobacter pylori: a critical review of the evidence. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:875–887. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.5.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaser M.J. Helicobacter pylori and the pathogenesis of gastroduodenal inflammation. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:626–633. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cover T.L., Blaser M.J. Helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal disease. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:135–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forman D., Webb P., Newell D.G. An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Lancet. 1993;341:1359–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oderda G., Vaira D., Holton J. Helicobacter pylori in children with peptic ulcer and their families. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:572–576. doi: 10.1007/BF01297021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drumm B., Perez G., Blaser M.J., Sherman P.M. Intrafamilial clustering of Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:359–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002083220603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han S., Zschausch H.E., Meyer H.W. Helicobacter pylori: clonal population structure and restricted transmission within families revealed by molecular typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3646–3651. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.10.3646-3651.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohmer C.J., Klinkenberg-Knol E.C., Kuipers E.J. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among inhabitants and healthy employees of institutes for the intellectually disabled. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1000–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert J.R., Lin S.K., Sievert W., Nicholson L., Schembri M., Guest C. High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori antibodies in an institutionalized population: evidence for person-to-person transmission. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2167–2171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammermeister L., Janus G., Schamarovsi F., Rudolf M., Jacobs E., Kist M. Elevated risk of Helicobacter pylori infection in submarine crews. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:9–14. doi: 10.1007/BF01971264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dore M., Osato M., Malaty H., Graham Y. Characterization of a culture method to recover Helicobacter pylori from the feces of infected patients. Helicobacter. 2000;5:165–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsonnet J., Shmuely H., Haggerty T. Fecal and oral shedding of Helicobacter pylori from healthy infected adults. JAMA. 1999;282:2240–2245. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Axon A.T.R. The transmission of Helicobacter pylori: which theory fits the facts? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:1–2. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199601000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaira D., Holton J., Ricci C. Review article: the transmission of Helicobacter pylori from stomach to stomach. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15(Suppl. 1):33–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris A., Lloyd G., Nicholson G. Campylobacter pyloridis serology among gastroendoscopy clinic staff. N Z Med J. 1986;99:819–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pristautz H., Eherer A., Brezinschek R. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori antibodies in the serum of gastroenterologists in Austria. Endoscopy. 1994;26:690–696. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudi J., Toppe H., Marx N. Risk of infection with Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis A virus in different groups of hospital workers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:258–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matysiak-Budnik T., Megraud F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection with special reference to professional risk. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;48(Suppl. 4):3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braden B., Duan L.P., Caspary W.F., Lembke B. Endoscopy is not a risk factor for Helicobacter pylori infection but medical practice is. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:305–310. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monés J., Martin-de-Argila C., Samitier R.S., Gisbert J.P., Sainz S., Boixeda D. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in medical professionals in Spain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:239–242. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199903000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goh K.L., Parasakathi N., Ong K.K. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in endoscopy and non-endoscopy personnel: results of field survey with serology and 14C-urea breath test. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:268–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chong J., Marshall B.J., Barkin J.S. Occupational exposure to Helicobacter pylori for the endoscopy professional: a sera epidemiological study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1987–1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hildebrand P., Meyer-Wyss B.M., Mossi S., Beglinger C. Risk among gastroenterologists of acquiring H. pylori infection: case-control study. BMJ. 2000;321:149. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7254.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishikawa J., Kawai H., Takahashi A. Seroprevalence of immunoglobulin G antibodies against Helicobacter pylori among endoscopy personnel in Japan. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:237–243. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin S.K., Lambert J.R., Schembri M.A., Nicholson L., Korman M.G. Helicobacter pylori prevalence in endoscopy and medical staff. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;9:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1994.tb01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W.Z., Xiao S.D., Jiang S.J., Li R.R., Pang Z.J. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in medical staff in Shanghai. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:749–752. doi: 10.3109/00365529609010346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palli D., Vaira D., Menagatti M., Saieva C. A serologic survey of Helicobacter pylori infection in 3281 Italian patients endoscoped for upper gastrointestinal symptoms. The Italian Helicobacter pylori Study Group. Aliment Pharm Therapeut. 1997;11:719–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gasbarrini A., Anti M., Franceschi F. Prevalence and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection among healthcare workers at a teaching hospital in Rome: the Catholic University Epidemiological study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:185–189. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200102000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petrosillo N., Puro V., Ippolito G. Hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus infection in healthcare workers: a multiple regression analysis of risk factors. J Hosp Infect. 1995;30:273–281. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(95)90262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garber E., San Gabriel P., Lambert L., Saiman L. A survey of latent tuberculosis among laboratory healthcare workers in New York City. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:801–806. doi: 10.1086/502140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee N., David H., Wu A. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robertson M.S., Cade J.F., Clancy R.L. Helicobacter pylori infection in intensive care: increased prevalence and a new nosocomial infection. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1276–1280. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Voort P.H.J., van der Hulst R.W.M., Zandstra D.F. Gut decontamination of critically ill patients reduces Helicobacter pylori acquisition by intensive care nurses. J Hosp Infect. 2001;47:41–45. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2000.0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marshall B.J., Warren J.R. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]