Summary

Guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organisation state that healthcare workers should wear N95 masks or higher-level protection during all contact with suspected severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). In areas where N95 masks are not available, multiple layers of surgical masks have been tried to prevent transmission of SARS. The in vivo filtration capacity of a single surgical mask is known to be poor. However, the filtration capacity of a combination of masks is unknown.

This was a crossover trial of one, two, three and five surgical masks in six volunteers to determine the in vivo filtration efficiency of wearing more than one surgical mask. We used a Portacount to measure the difference in ambient particle counts inside and outside the masks. The best combination of five surgical masks scored a fit factor of 13.7, which is well below the minimum level of 100 required for a half face respirator.

Multiple surgical masks filter ambient particles poorly. They should not be used as a substitute for N95 masks unless there is no alternative.

Keywords: Respiratory protective devices, Severe acute respiratory syndrome, Safety, Occupational, Disease transmission, Patient to professional, Aerosols, Infection control

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a highly contagious, potentially life-threatening condition that frequently affects healthcare workers caring for infected patients.1 The exact mode of transmission is unknown but may involve airborne as well as respiratory droplet and fomite spread. In view of the possibility of airborne transmission, current guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) state that healthcare workers should wear N95 masks or higher-level protection during all contact with suspected SARS patients. These masks are expensive and not necessarily easily available in poorer countries. In some areas, multiple layers of surgical masks have been tried to prevent SARS transmission.

The filtration capacity of a single surgical mask is known to be poor.2 It is not known whether this improves when more than one mask is worn simultaneously.

Methods

This was a prospective unblinded study of six healthy volunteers using combinations of one, two, three or five surgical masks (Surgikos, Johnson & Johnson, Arlington, TX, USA). The Surgikos mask is a pleated rectangular three-ply mask with a bacterial filtration efficiency of 95% at 3 μm. All volunteers gave written informed consent. Approval was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

All six volunteers underwent a set of tests with each of the combinations of masks. These involved standard testing procedures using a protocol described previously.3 In brief, the tests consisted of comparisons of particle counts inside and outside the masks during a series of activities: normal breathing, deep breathing, turning the head from side to side, flexing and extending the head, talking loudly, and bending over followed by normal breathing again. The tube for sampling the mask particle count was connected to a test probe that was inserted through the fabric of the protective device. The probes were provided by TSI (TSI Incorporated, St Paul, MI, USA) for this purpose. The design of the probe is such that there is no leak around the insertion point, so the efficiency of the mask at filtering ambient particles should remain unchanged. The insertion site was centrally in the area directly in front of the mouth, as per the instructions for use provided by TSI. The tube for sampling the ambient particle count was fixed approximately 3 cm from the sampling probe.

A PortaCount Plus (TSI Incorporated) connected to a computer running FitPlus for Windows software (TSI Incorporated) was used to count particles and calculate the ratio of ambient to device particle counts. This device counts all particles with a diameter between 0.02 and 1 μm. It calculates a fit factor, which is the average ratio of atmospheric to device particle concentrations. The equation used is:

where N is the number of exercises performed and ffj is the fit factor for the individual exercise.

One modification was made to the PortaCount Plus. The re-usable tubing supplied by the manufacturer was replaced with disposable PVC tubing of the same internal diameter and length to minimize any risk of cross-infection. To ensure an adequate ambient particle count throughout the testing, the 8026 Particle Generator (TSI Incorporated) was used to generate saline particles throughout the testing procedures. Each surgical mask was tied separately.

The American National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health requirements for a half mask respirator are that it should have an assigned protection factor of 10.4 Further to this, a safety factor of 10 is required when conducting performance or fit testing, so a half face respirator should achieve a minimum fit factor of 100.

Data obtained while wearing one mask were compared with data obtained while wearing five masks using a paired t-test (Statview 5.0, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A P value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

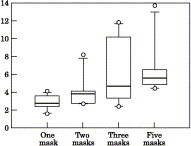

Results of the filtration capacity of the devices are shown in Figure 1 . The median reduction in particle count for a single surgical mask was 2.7. This increased to 5.5 with five surgical masks. The difference in particle count reduction in a given subject between one and five surgical masks ranged from 1.6 to 4.2. The best particle count reduction with five surgical masks was 13.7 times, which is less than the required value of 100 for a half face respirator.

Figure 1.

Particle count reductions seen with varying numbers of surgical masks. Median values for one, two, three and five masks were 2.7, 3.8, 4.6 and 5.5, respectively. The boxes outline the 25th and 75th centiles, the bars indicate the 10th and 90th centiles and the circles indicate the outlying values. A half face respirator such as an N95 mask should achieve a minimum 100-fold reduction in particle count.

Discussion

Our data confirm previous findings that the filtration of submicron-sized airborne particles by a single surgical mask is minimal. The ratio of the concentration of particles inside the mask to the concentration in ambient air was only 2.7. Although greater filtration was afforded by multiple masks, with an approximate doubling in the filtration factor when five masks were worn compared with a single mask, the absolute filtration factor remained low and well below the minimum fit factor of 100 required for a respirator. For this reason, even multiple masks are not a suitable alternative to N95 masks when the latter are available.

The more difficult question to answer is whether the use of multiple masks provides significant, albeit suboptimal, protection against infection with SARS Co-V. This is likely to depend on the route of transmission of SARS Co-V, the viral load required to cause infection and the degree of viral shedding by the patients.

Surgical masks are designed to prevent the wearer from transmitting infection to others, but do provide some protection against respiratory droplet and fomite spread. If SARS Co-V is not transmitted by airborne particles but only by respiratory droplets and fomites, even one surgical mask is likely to protect the user to a significant degree. If the virus is spread by airborne transmission, the likelihood that surgical masks will provide significant protection is dependent on the viral load required to cause infection and the degree of viral shedding by the patient(s). If the number of viruses required to produce clinically significant infection is low and large numbers of viruses are shed by patients, it is unlikely that even multiple surgical masks will provide significant protection. If, however, large numbers of viruses are required and small numbers are shed, it is more likely that multiple surgical masks will provide significant protection. Unfortunately, those data are not available, although an epidemiological study has suggested that SARS is only moderately infectious.5

Data from a recent retrospective multiple logistic regression study suggest that surgical masks may afford significant protection against SARS. This study showed that wearing either a N95 mask or a surgical mask reduced the risk of contracting SARS with little difference in risk reduction.6 These data must be treated with considerable caution for two reasons. Firstly, the authors took no account of the degree of exposure of the wearers to high-risk situations. It is likely that staff exposed to high-risk situations would be more likely to wear a N95 mask, while those only exposed to low-risk situations would be more likely to wear a surgical mask. Without controlling for this confounding factor, it is not reasonable to compare the two types of mask. Secondly, the number of staff who contracted SARS was too small to allow meaningful multiple logistic regression analysis.

One limitation of the study is that the Portacount measures dust particles of less than 1 μm in size rather than SARS CoV. If SARS CoV is carried on larger particles, it is possible that the masks may provide better protection than our results suggest. On the other hand, surgical instruments are known to produce submicron-sized particles that carry viable viral particles.7 Furthermore, a study has shown that particles of up to 22 μm in size enter the respiratory zone when these masks are worn.8

In conclusion, our data show that no combination of multiple surgical masks was able to meet the requirements for a respirator. If protection against airborne organisms is required, an N95 respirator or better should be used, as currently recommended by the CDC and WHO guidelines for SARS prevention. Multiple surgical masks will reduce the number of viruses inhaled, but whether the degree of reduction is sufficient to produce significant protection is unknown and cannot be predicted at present. Multiple surgical masks should, therefore, only be used if N95 masks are not available.

References

- 1.Lee N., Hui D., Wu A. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber A., Willeke K., Marchioni R. Aerosol penetration and leakage characteristics of masks used in the health care industry. Am J Infect Control. 1993;21:167–173. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(93)90027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Respiratory protection. Code of Federal Regulations Title 29. Part 1910.134. Washington DC: Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration; 1997.

- 4.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health . US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Center for Disease Control, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; Morgantown, West Virginia: 1987. NIOSH respirator decision logic. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley S., Fraser C., Donnelly C.A. Transmission dynamics of the etiological agent of SARS in Hong Kong: impact of public health interventions. Science. 2003;300:1961–1966. doi: 10.1126/science.1086478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seto W.H., Tsang D., Yung R.W. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Lancet. 2003;361:1519–1520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13168-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jewett D.L., Heinsohn P., Bennett C., Rosen A., Neuilly C. Blood-containing aerosols generated by surgical techniques. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1992;53:228–231. doi: 10.1080/15298669291359564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pippin D.J., Verderame R.A., Weber K.K. Efficacy of face masks in preventing inhalation of airborne contaminants: a possible infectious hazard. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;45:319–323. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(87)90352-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]