Abstract

In hospitals, the ventilation of isolation rooms operating under closed-door conditions is vital if the spread of viruses and infection is to be contained. Engineering simulation, which employs computational fluid dynamics, provides a convenient means of investigating airflow behaviour in isolation rooms for various ventilation arrangements. A cough model was constructed to permit the numerical simulation of virus diffusion inside an isolation room for different ventilation system configurations. An analysis of the region of droplet fallout and the dilution time of virus diffusion of coughed gas in the isolation room was also performed for each ventilation arrangement. The numerical results presented in this paper indicate that the parallel-directional airflow pattern is the most effective means of controlling flows containing virus droplets. Additionally, staggering the positions of the supply vents at the door end of the room relative to the exhaust vents on the wall behind the bed head provides effective infection control and containment. These results suggest that this particular ventilation arrangement enhances the safety of staff when performing medical treatments within isolation rooms.

Keywords: Virus diffusion, Isolation rooms, Infection control and containment, Computational fluid dynamics (CFD)

Introduction

Fundamental guidelines for infection control in hospital environments were posted on the World Health Organization's (WHO) website on 24 April 2003 during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak which was ongoing at that time. These guidelines advised that all individuals showing potential SARS-related symptoms should be promptly quarantined in an isolation room. According to SARS statistics published later in 2003 by the WHO,1 this action was instrumental in minimizing the spread of the disease within hospitals caring for SARS victims. For effective infection control, it is essential to maintain a negative pressure between the isolation room and the outside environment. However, a review of the international standards2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 shows that the specified minimum pressure differentials between the isolated field and the non-isolated field vary considerably, i.e. from 2.5 Pa to 30 Pa, and are not even specified in some cases. The tracer containment testing of isolation rooms performed by Rydock and Eian8 showed that even when the isolation room was established at a high pressure differential of 15 Pa and a high ventilation rate of 15–21 air changes/h was maintained, leaked gases from the isolation room could still be detected in the anteroom for up to 3 min following the opening of the interconnecting door.

The effective functioning of an isolation room operating under closed-door conditions is highly dependent upon the particular ventilation airflow patterns established within the room. Appropriate flow directions within the isolation room prevent diffusion of the virus via airborne or droplet transmission mechanisms. Hence, the risk of leakage when the door of the isolation room is opened is minimized. Moreover, the reliability of infection control and the safety of personnel when conducting medical treatments in the isolation room are greatly enhanced.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) numerical simulations provide a powerful and reliable tool for investigating the variable airflow patterns associated with ventilation problems involving variable flow behaviours and directions. This study simulated the air flows associated with various ventilation arrangements, and then used a cough model to investigate virus diffusion via droplet fallout for each ventilation system by means of time-accurate numerical simulations. The critical region of droplet fallout is presented for each ventilation arrangement in order to analyse the level of infection control afforded by each configuration, thereby providing an indication of the safety of performing medical treatments within the isolation room.

Methods

In general, an ideal ventilation system should establish its optimal airflow pattern inside an isolation room, such that clean air from the air-supply vents may carry the air across infectious sources, and then flow through the exhaust vents completely. This paper investigates the airflow patterns associated with various ventilation arrangements, in order to develop an understanding of the effects of these arrangements on the regions of droplet fallout.

Simulation model of an isolation room

To ensure effective control of virus containment in an isolation room, the door must be closed as often as practical so that the air flow can be maintained in a stable state. Therefore, the present study investigated the effectiveness of infection control for various ventilation arrangements in isolation rooms operating under closed-door conditions by considering the corresponding airflow patterns.

It is known that airflow patterns in isolation rooms are governed by the positions, areas, configurations and specified velocities/pressures of the air-supply and exhaust vents of the ventilation system. In accordance with international standards, this study generated various simulation models of an isolation room in order to reflect different ventilation arrangements. In all models, the patient was in a single room, positioned with the bed head in front of the wall containing the exhaust vents, away from the entrance of the isolation room.

In order to ensure the accuracy of the simulation results, the imposed conditions must reflect the operating conditions within an actual isolation room. For air supply, the inlet flow was specified to have a constant velocity of 0.4 m/s, and was calculated using an air-changing rate of 12 changes/h. The exhaust vents of the ventilation system were set at a constant outlet pressure of −8 Pa to maintain the negative pressure within the isolation room.

Cough model

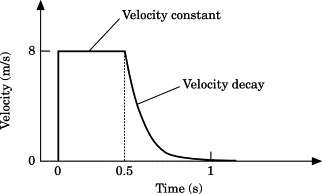

The proposed cough model was constructed based on flow-rate computation using hydrodynamics theory. This model assumed a 4000-mL capacity, which is the vital effective capacity of an adult's cough. The corresponding velocity profile is presented in Figure 1 . This profile was calculated on the basis of the assumed mouth area of a patient during the occurrence of a single cough of 1-s duration, formulated by the following equation:

| (1) |

Figure 1.

Velocity profile of cough model.

Numerical methods

The CFD numerical simulation is a useful tool for investigating gas convection and diffusion. An alternative tool is the tracer containment test, for practical measurement within a ready-made isolation room. Numerical simulation is performed on computers and therefore is a less expensive way to study airflow patterns resulting from various ventilation configurations.

The simulations in the current study used the FLUENT9 commercial CFD program with the SIMPLE (Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure Linked Equation) numerical method. The computational cells were mapped within the simulated isolation room with a total number of 460 948 cells, which were analysed by grid independence to ensure both computational accuracy and efficiency. In the present investigation, steady-state ventilation flows were computed and a time-accurate algorithm was used to obtain the region of droplet fallout and virus diffusion 5 s after the occurrence of a cough. In determining the critical region of droplet fallout and virus diffusion, it was assumed that the mole fraction of the coughed gas was more than 0.01. Meanwhile, the convergence criterion of the numerical computations was that the residuals of the variables were less than 10−3.

Results and discussion

Parallel-directional airflow pattern

The parallel-directional airflow pattern is recommended in the guidelines of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2 This pattern is established by locating the air-supply inlets in the wall opposite the patient, and exhausting the air from the wall behind the bed head. The recommended supply and exhaust vents are broadly rectangular in shape in order to ensure a stable direction of flow. The present study considered two different models of parallel-directional airflow: in model VC-01 (VC=ventilation case), the air-supply and exhaust vents are positioned at equal heights in the isolation room; and in model VC-02, the air-supply vents are positioned slightly higher than the exhaust vents.

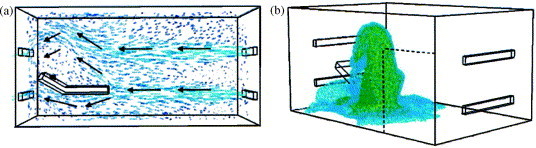

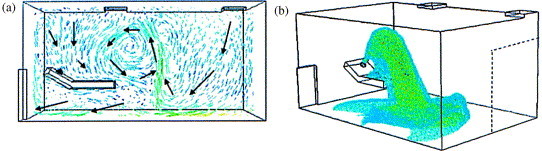

Figure 2 (a) presents the steady-state airflow vectors of model VC-01. The major directions of air flow are indicated by arrows. The air flow is uniform and stable, and has the same flow direction near the patient. Some smaller circulations with a slower velocity exist in the region immediately above the patient. As shown in Figure 2(b), these circulations contain the coughed droplets that fall in the region near the exhaust vents.

Figure 2.

Results of simulation model VC-01 for parallel-directional airflow pattern.

The simulation results for model VC-02 are shown in Figure 3 (a). In this case, the major air stream passes through the region above the patient and generates a circulation with an opposite direction to the major stream in the region below, close to the patient. The falling droplets are diffused slightly towards the corner near the door by the circulated flow existing in the region below the patient. However, as shown in Figure 3(b), the profile of the coughed gas is contained by the major stream above the patient.

Figure 3.

Results of simulation model VC-02 for parallel-directional airflow pattern.

Air supply from ceiling

This airflow pattern is recommended in the US CDC guidelines.2 In this ventilation arrangement, the inlet air is supplied from the ceiling of the isolation room, and the exhaust vents are located at floor level. Both the air-supply and exhaust vents have a square configuration. The present study considered two different models for this airflow pattern: models VC-03 and VC-04. In model VC-03, the two air-supply vents on the ceiling are positioned away from the corners of the room, towards the middle of the wall running parallel to the bed. Meanwhile, the two exhaust vents are located in the wall behind the patient and in the wall opposite the patient, and are positioned in the corners furthest away from the air-supply vents. In model VC-04, one air-supply vent is located in the ceiling at a position corresponding to the midpoint of the wall running parallel to the bed, while the second air-supply vent is located in the corner of the ceiling closest to the wall opposite the patient. Regarding the exhaust vents, a single vent is located at floor level in the corner of the wall behind the patient, situated as far as possible from the air-supply vents. The area of the exhaust vent in model VC-04 is equivalent to the total area of the two exhaust vents in model VC-03.

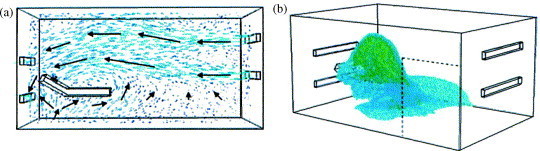

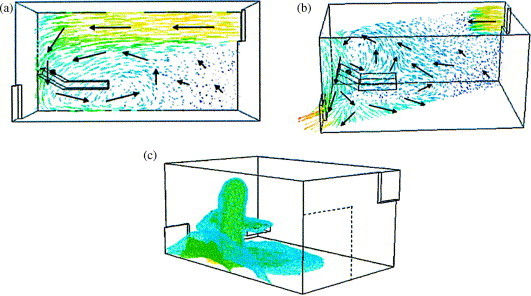

Figure 4 (a) and (b) present velocity vectors with the directional arrows of the major air stream in the cross-sections between these two air-supply vents and the corner exhaust vents, and in the cross-section located at the midwidth position of the room, respectively, for model VC-03 in steady state. Air flow is more rapid in the regions below the supply vents, and some circulating flows are generated near the patient. Meanwhile, the air flows in regions of the room away from the supply vents have reduced velocities and variable directions. Figure 4(c) shows that the region of droplet fallout and virus diffusion of coughed gas is enlarged by both the variable airflow direction and circulated flow regions near the patient.

Figure 4.

Results of simulation model VC-03 for air supply from ceiling.

The velocity vectors of model VC-04 shown in Figure 5 (a) show that the bed tends to block the air flow. A circulation region is generated at the end of, and slightly above, the foot of the bed, which causes the main ventilation flow to become more complicated. As shown in Figure 5(b), the profile of coughed gas is changed by variable flow directions and differential velocity magnitudes of the circulation near the patient.

Figure 5.

Results of simulation model VC-04 for air supply from ceiling.

The simulation results for these models indicate that the placement of air-supply inlets in the ceiling results in variable-direction air flows. Furthermore, the flow in the region between the two air-supply vents interacts with the unstable flows, resulting in the generation of an up-flow draft. From a comparison of the results presented in this section with those presented previously for parallel-directional airflow patterns, it is clear that the region of droplet fallout is enlarged when air-supply inlets are positioned in the ceiling.

Single air-supply and exhaust vents in diagonal corners of the isolation room

Model VC-05 shows the airflow pattern when single air-supply and exhaust vents are positioned in diagonal corners of the isolation room. This particular flow pattern is designed to enhance the air-changing efficiency within the room.

In this model, there are no exhaust vents in the corresponding position of the wall at the patient end of the room opposite the supply vent. Hence, a circulation is generated to the left of the patient opposite the supply vent, as shown in Figure 6 (a). Furthermore, Figure 6(b) shows that additional circulations are generated to the right of the patient along the diagonal cross-section between the air-supply vent and the exhaust vent. These circulations cause the region of droplet fallout to broaden along the sidewall, as shown in Figure 6(c). This effect can be exploited to enhance the safety of conducting medical treatments in the isolation room.

Figure 6.

Results of simulation model VC-05 for single air-supply and exhaust vents at diagonal corners of room.

Staggered air-supply and exhaust vents

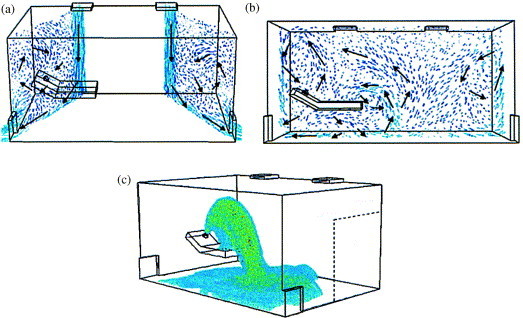

The simulation results presented in the previous sections indicate that the parallel-directional airflow pattern ensures the optimum containment of coughed gas, and maximizes control of the region. Furthermore, the results of model VC-05 show that positioning the air-supply and exhaust vents in diametrically opposite corners changes both the direction and location of the region of droplet fallout and virus diffusion of coughed gas. Therefore, this section of the paper investigates the effect on the parallel-directional airflow pattern of staggering the positions of the air-supply and exhaust vents (models VC-06 and VC-07). Comparing the two models, the exhaust vents in the vertical direction are identical and the air-supply vents are located at different positions (Figure 7, Figure 8 ).

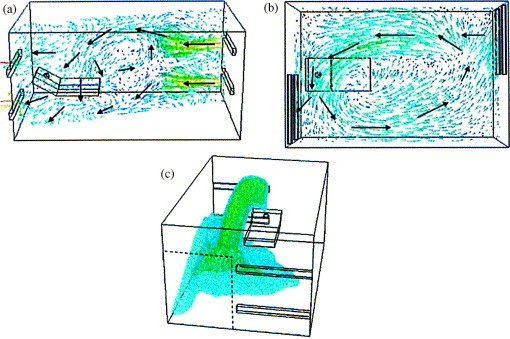

Figure 7.

Results of simulation model VC-06 showing the effect of staggered positions of air-supply and exhaust vents on a parallel-directional airflow pattern.

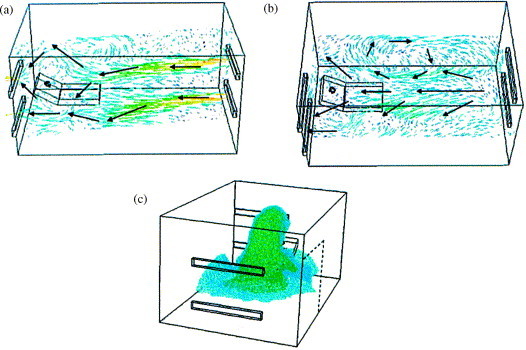

Figure 8.

Results of simulation model VC-07 showing the effect of staggered positions of air-supply and exhaust vents on a parallel-directional airflow pattern.

In model VC-06, the two sets of vents are staggered completely relative to one another. Hence, as shown in Figure 7(a), airflow circulations are established near the foot of the bed. Meanwhile, Figure 7(b) shows the presence of a major horizontal circulation in the region of the room bounded vertically by the upper and lower air-supply and exhaust vents. As shown in Figure 7(c), the region of droplet fallout broadens along the sidewall of the room under the influence of this major horizontal circulation flow.

In model VC-07, the positions of the inlet and exhaust vents are partially overlapped and partially staggered (as opposed to completely staggered, as in the example presented above). In this arrangement, the air inlets are located in the middle of the end wall opposite the patient, and the exhaust vents located in the facing wall are offset towards the corner of the room. Figure 8(a) shows that circulations are located behind the patient. Additionally, the velocity magnitude distribution is more uniform. As shown in Figure 8(b), in contrast to the previous case, less horizontal circulation is generated in the region of the room bounded by the upper and lower vents. Consequently, less coughed gas is diffused towards the door end of the room. Figure 8(c) shows that the coughed gas with infectious droplets is contained near the patient and around the exhaust vents. Significantly, model VC-07 demonstrates the smallest region of droplet fallout and virus diffusion of coughed gas. Therefore, this particular ventilation arrangement provides good results for infection control, and enhances staff safety when performing medical treatments inside the isolation room.

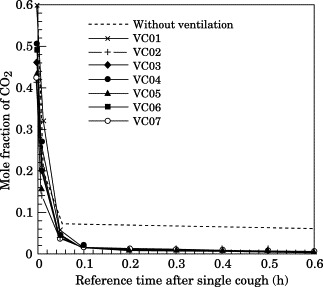

Diluting effect for various ventilation arrangements

It would be valuable to estimate the time required for cough gas to dilute in isolation rooms. The maximum concentrations of cough gas for various models are plotted in Figure 9 . This result suggests that the diluting effect within an isolation room is dependent on the air-changing rate, but is nearly independent of the airflow pattern. However, as shown by the simulation results presented in the sections above, different airflow patterns lead to different airflow behaviours inside the room, and hence have different containment effects. Therefore, the airflow patterns are an important and significant parameter when designing ventilation systems to enhance the efficiency of infection control within isolation rooms.

Figure 9.

Diluting time after a single cough for each airflow pattern.

The above results are based on the occurrence of a single cough. However, most patients with infective symptoms may cough regularly. For this reason, the case of a patient with frequent coughing must be considered for the practical operation of an isolation system. A few simulations have been performed in order to consider the effect of frequent coughing on the design of ventilation configuration. Simulated results showed that the droplet fallout region is not broadened in the case of frequent coughing, and dispersion of infective droplets is not significantly influenced by the gravity effect in the isolation room when air flow within the room is in the steady state. However, for a patient with frequent coughing, the concentration of coughed gas will increase inside the isolation room. The increased concentration depends on the frequency (coughs/min) and the duration of a sustained burst of coughing, so the required diluting time can be calculated by the following equation8:

| (2) |

where ACH is the air-changing rate, C m is the maximum concentration of coughed gas after a sustained burst of coughing, and C s is a specified safety concentration inside the isolation room. Our simulated results agree well with the above relation.

Conclusions

Isolation rooms in hospitals are required to provide the functions of infection control and safety during the performance of medical treatments. The present study has used an engineering computational technique to develop an understanding of containment in an isolation room when the door is kept closed, such that virus diffusion is influenced by ventilation airflow patterns alone. The current simulation results yield a number of significant findings and recommendations for the operation of isolation rooms.

The diluting efficiency depends on the air-changing rate, and is nearly independent of the airflow patterns. However, the airflow pattern is a significant parameter influencing the region of droplet fallout and virus diffusion within the isolation room when the door is kept closed. The present results have shown that positioning the air-supply inlets in the ceiling and the exhaust vents at floor level results in an up-draft effect and poor infection control efficiency. The parallel-directional airflow pattern results in a uniform flow path with a stable direction of flow. This arrangement achieves the best containment efficiency of the various ventilation systems considered in the present study.

This study has also considered the effect of using staggered inlet and exhaust vents on the parallel-directional airflow pattern. It has been shown that when the air-supply inlets are located in the middle of the wall at the door end of the room, and the exhaust vents are positioned in the wall behind the patient towards the corner of the room, the coughed gas is contained to the side of the patient in the region of the exhaust vents. This minimizes the region of coughed gas diffusion and droplet fallout. Accordingly, this particular ventilation system improves the control and containment of infection, thereby enhancing the safety of staff when performing medical treatments inside the isolation room.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Science Council of Taiwan under Grant No. 92-2751-B-006-011-Y.

References

- 1.Department of Communicable Disease Surveillance and Response, World Health Organization . 2003. Consensus document on the epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (Global Health Security, Epidemic Alert and Response.). p. 1—44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care facilities. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1994;43:1–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guidelines for environmental infection control in health-care facilities. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52:1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Institute for Architects, Academy of Architecture for Health . The American Institute of Architects; Washington, DC: 2001. Guidelines for design and construction of hospital and health-care facilities. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Human Services in Australia . Department of Human Services in Australia; 1999. Guidelines for the classification and design of isolation rooms. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Interdepartmental Working Group on Tuberculosis, UK Department of Health . 1998. The prevention and control of tuberculosis in the United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health Canada, Health Protection Branch-Laboratory Center for Disease Control. Guidelines for preventing the transmission of tuberculosis in Canadian health-care facilities and other institutional settings. Can Commun Dis Rep 1996; 22 (Suppl 22): 1—50. [PubMed]

- 8.Rydock J.P., Eian P.K. Containment testing of isolation rooms. J Hosp Infect. 2004;57:228–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FLUENT. Computational fluid dynamics software, version 6.1. Fluent Incorporated; 2004.