Abstract

As part of the quest for new gold drugs, we have explored the efficacy of three gold complexes derived from the tuberculosis drug pyrazinamide (PZA), namely, the gold(I) complex [Au(PPh3)(PZA)]OTf (1, OTf = trifluoromethanesulfonate) and two gold(III) complexes [Au(PZA)Cl2] (2) and [Au(PZO)Cl2] (3, PZO = pyrazinoic acid, the metabolic product of PZA) against two mycobacteria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis. Only complex 1 with the {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety exhibits significant bactericidal activity against both strains. In the presence of thiols, 1 gives rise to free PZA and {Au(PPh3)}-thiol polymeric species. A combination of PZA and the {Au(PPh3)}-thiol polymeric species appears to lead to enhanced efficacy of 1 against M. tuberculosis.

Introduction

Gold-based treatment of various diseases has been around for hundreds of years.1 This area of research was made popular in the late 1800s when Robert Koch discovered gold cyanide to be effective against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB).2 His work inspired numerous others to further research gold as a possible potent antimicrobial agent. Eventually, the toxicity of gold compounds halted their clinical use for the treatment of TB but later became popular for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.3 Auranofin, an antiarthritic drug, was approved for clinical use in the 1980s and continues to be administered today along with various other gold compounds.4

The success of auranofin and the rapid increase in drug-resistant pathogens prompted a surge of new research into gold compounds and their broad use as antiarthritic, antimicrobial, anticancer, and antifungal agents.5−7 Gold(III) complexes, sharing the same geometrical shape as the well-known cancer therapeutic cisplatin, have been evaluated for their anticancer effect and often show increased activity with no cross-resistance to cisplatin.8,9 Antimicrobial gold(I) and (III) complexes have been investigated for their potency against numerous strains of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria showing promising results.6 So far, research in this area has implied that ligand structures of the gold complexes play important roles in both their efficacy and toxicity. In particular, manipulation of ligand structures was shown to affect the passage of the therapeutics across hydrophobic membranes of target cells to a significant extent.6,10,11 An important class of gold(I) compounds, those with triphenylphosphine as ligands, is emerging as effective therapeutics against bacterial infection10,11 and cancer (Figure 1).12−14 The results of our previous work on cationic gold(I) triphenylphosphine complexes have implied that the highly reactive and lipophilic {Au(PPh3)}+ unit plays an important role in their antibacterial activity.11 Although gold(I) complexes have been studied for their anticancer and antibacterial effectiveness, to our knowledge only two gold(I) complexes with the {Au(PPh3)}+ unit have so far been evaluated for their antimycobacterial behavior.15,16

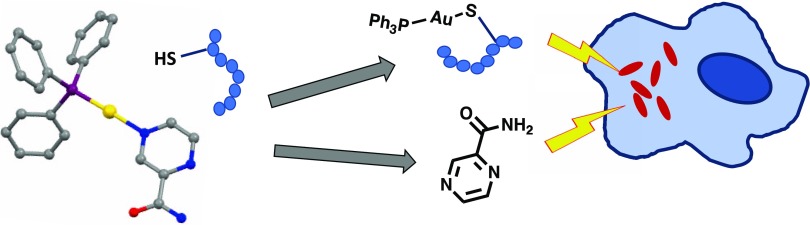

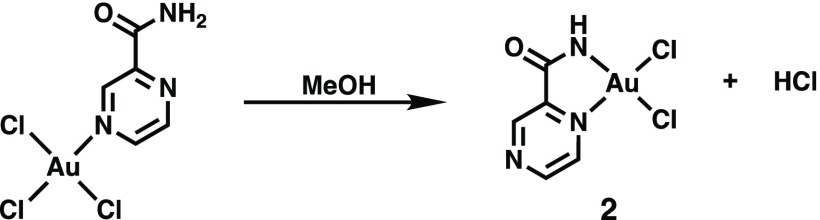

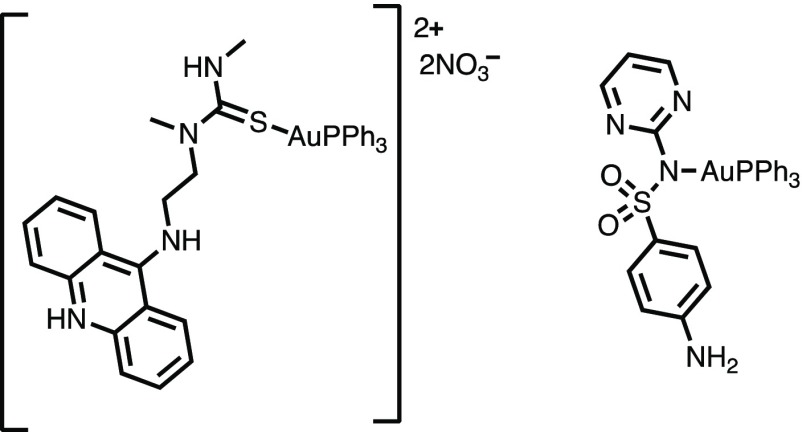

Figure 1.

Structures of complexes with the {Au(PPh3)}+ unit that have shown anticancer (A, B)13,14 and antibacterial (C, D)10,11 activity.

Recent efforts in drug discovery have demonstrated that combination of two antipathogenic moieties in one chemotherapeutic often leads to higher overall efficacy.11−16 It is evident that such a design provides a dual mechanism of action and potentially increased the effect compared to that of the ligand or the metal center on its own. Along this line, we have reported Au(I) and Ag(I) complexes of benzothiazoles that exhibit high antibacterial activity against Acenetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus. Success in these cases prompted us to explore the possibility of designing new gold(I) complexes comprising the {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety and the known TB drug pyrazinamide (PZA). PZA shortens the treatment duration for TB to a considerable extent although large oral quantities are needed for such effect.17 We therefore decided to combine PZA with the {Au(PPh3)}+ unit and study the synergistic effects (if any) on M. tuberculosis and the possibility of use of lower doses of PZA.

Herein, we report the syntheses and characterization of one gold(I) complex [Au(PPh3)(PZA)]OTf (1, OTf = trifluoromethanesulfonate) and two gold(III) complexes [Au(PZA)Cl2] (2) and [Au(PZO)Cl2] (3, PZO = pyrazinoic acid, the metabolic product of PZA). The antimycobacterial properties of these complexes have been evaluated on both M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium smegmatis.

Experimental Section

General

All reagents and solvents were of commercial grade and used without further purification. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were obtained using a PerkinElmer Spectrum One spectrophotometer. 1H, 13C, 31P, and 19F nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded using a Varian Unity 500 MHz instrument at 298 K.

Syntheses

[Au(PPh3)(PZA)]OTf (1)

A solution of 72.0 mg (0.28 mmol) of silver trifluoromethanesulfonate (OTf) in 10 mL of methanol was added to a solution of 138.8 mg (0.28 mmol) of chloro(triphenylphosphine)gold(I) dissolved in 15 mL of chloroform. Immediately, a suspension of AgCl was formed and the mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature and then filtered through a bed of celite. To the filtrate, a solution of 34.4 mg (0.28 mmol) of PZA in 15 mL of methanol/chloroform (1:1) was added, and the mixture was stirred for 18 h at room temperature. The flask was covered with an Al foil to protect the reaction mixture from ambient light. Next, the solvent was removed in vacuo, and the solid was washed with diethyl ether to obtain 1 as a white solid (112.1 mg, 54%). A solution of the solid in chloroform was layered with hexanes and stored in the fridge. X-ray quality crystals of 1 were obtained after 1 week. Anal. calc. for C24H20AuN3O4PSF3: C, 39.41; H, 2.76; N 5.74; found: C, 39.35,; H, 2.79, N, 5.68. IR (KBr, cm–1): 3435(m), 3309(m), 1690(s), 1438(m), 1262(s), 1167(m), 1031(m), 693(m). 1H NMR (CD3OD, δ ppm): 9.40 (b, 1H), 9.03 (b, 1H), 8.96 (b, 1H), 7.69–6.58 (m, 15H). 13C (CDCl3, δ ppm): 148.18, 146.38, 144.29, 134.26, 134.16, 132.54, 132.52, 129.64, 129.55, 127.55, 127.03. 31P (MeOD, referenced to PPh3), 34.88.

[Au(PZA)Cl2] (2)

A batch of 32.5 mg (0.26 mmol) of PZA was dissolved in 2 mL of water and the solution was added dropwise to a solution of 99.7 mg (0.26 mmol) of potassium tetrachloroaurate in 1.75 mL of water at room temperature with stirring. A yellow solid appeared quickly, and the suspension was allowed to stir for an additional 10 min. The precipitate was filtered, washed with 2 mL of cold water and then 10 mL of cold diethyl ether to obtain the precursor complex (vide infra) as a bright yellow solid (90 mg). IR (KBr, cm–1): 3442(m), 1704(s), 1373(m), 1177(w), 560(w). 1H NMR (CD3CN, ppm): 9.53 (s, 1H), 9.07 (d, 1H), 9.05 (d, 1H), 7.68 (b, 1H), 6.60 (b, 1H). The precursor yellow solid was crystallized by slow evaporation in methanol to form orange blocks of 2 after 2 weeks. Anal. calc. for C5H4AuN3OCl2: C, 15.40; H, 1.03; N, 10.77; found: C, 15.38; H, 1.10; N, 10.73. IR (KBr, cm–1): 3167(m), 1660(s), 1584(m), 1421(w), 1348(m), 1166(w) 1065(w), 579(w). 1H NMR (CD3CN, δ ppm): 9.26 (m, 2H), 9.21 (s, 1H), 7.24 (b, 1H). 13C ((CD3)2SO, δ ppm): 171.27, 152.97, 149.89, 141.50, 138.46.

[Au(PZO)Cl2] (3)

An aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide (0.15 M) was used to adjust the pH of a suspension of 100 mg (0.81 mmol) of PZO in 2 mL of water until a pH of 7 was reached. At this point, PZO had fully dissolved and the solution was added dropwise to a solution of 101.5 mg (0.27 mmol) of potassium tetrachloroaurate in 1 mL of water at room temperature with stirring. A light yellow precipitate appeared within minutes. After stirring for an additional 30 min, the solid was filtered, washed with 2 mL of cold water and then 5 mL of diethyl ether. The light yellow solid was finally recrystallized from MeOH/ether to yield 3 as a yellow microcrystalline solid (60.2 mg, 55%). X-ray quality crystals were formed by the layering of acetonitrile/ether. Anal. calc. for C5H3AuN2O2Cl2: C, 15.36; H, 0.77; N, 7.17; found: C, 15.40; H, 0.81; N, 7.13. IR (KBr, cm–1): 3586 (m), 3419 (m), 1705(s), 1616(s), 1408(m), 1376(s), 1138(m), 850 (w), 795(w). 1H NMR (CD3CN, δ ppm): 9.31 (m, 2H), 9.12 (d, 1H). 13C (CD3CN, δ ppm): 170.00, 154.09, 151.53, 139.90, 137.35.

X-ray Crystallography

Crystallographic data were collected on a Bruker APEX II single-crystal X-ray diffractometer (PHOTON 100 detector) with graphite monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) by the ω-scan technique in the range 5.8 ≤ 2θ ≤ 53 for (1), 7 ≤ 2θ ≤ 50 for (2), and 6.2 ≤ 2θ ≤ 50 for (3) (Table 1). All data were corrected for Lorentz and polarization effects.18 All of the structures were solved with the aid of the SHELXT program using intrinsic phasing.19 The structures were then refined by a full-matrix least-squares procedure on F2 by SHELXL.20 All nonhydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. All hydrogen atoms were included in calculated positions. The absorption corrections are done using SADABS.19 Calculations were performed using the OLEX221 and SHELXTL(22) (V 6.14) program package.

Table 1. Crystal Data and Structure Refinement Parameters for 1·H2O, 2, and 3.

| 1·H2O | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| formula | C23H20AuN3OP·CF3O3S·H2O | C5H4AuCl2N3O | C5H3AuCl2N2O2 |

| Dcalc. (g cm–3) | 1.835 | 3.135 | 3.013 |

| μ (mm–1) | 5.62 | 18.4 | 17.65 |

| formula weight | 749.44 | 389.98 | 390.96 |

| color | colorless | yellow | yellow |

| shape | block | block | plate |

| T (K) | 298 | 298 | 298 |

| crystal system | triclinic | triclinic | orthorhombic |

| space group | P1 | P1 | Pbca |

| a (Å) | 7.0334 (10) | 6.6857 (10) | 7.2868 (6) |

| b (Å) | 12.6524 (16) | 7.2848 (11) | 14.4003 (12) |

| c (Å) | 15.688 (2) | 8.9057 (13) | 16.4259 (13) |

| α (°) | 79.435 (4) | 94.664 (2) | 90 |

| β (°) | 81.214 (5) | 106.878 (2) | 90 |

| γ (°) | 89.464 (4) | 91.649 (2) | 90 |

| V (Å3) | 1356.0 (3) | 413.06 (11) | 1723.6 (2) |

| Z | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| wavelength (Å) | 0.71073 | 0.71076 | 0.71076 |

| radiation type | Mo Kα | Mo Kα | Mo Kα |

| 2θmin (°) | 5.8 | 7 | 6.2 |

| 2θmax (°) | 52.8 | 49.6 | 49.4 |

| measured refl. | 24 132 | 4259 | 15 095 |

| independent refl. | 5469 | 1395 | 1462 |

| reflections used | 5027 | 1381 | 1261 |

| Rint | 0.025 | 0.019 | 0.044 |

| parameters | 343 | 113 | 109 |

| GooFa | 1.14 | 1.2 | 1.08 |

| wR2c | 0.122 | 0.043 | 0.067 |

| R1c | 0.044 | 0.017 | 0.024 |

GOF = [∑[w(Fo2 – Fc)2]/(No – Nv)]1/2 (No = number of observations, Nv = number of variables).

wR2 = [(∑w(Fo2 – Fc)2/∑|Fo|2)]1/2.

R1 = ∑||Fo| – |Fc||/∑|Fo|.

Mycobacterial Studies

M. smegmatis

Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium23 was inoculated from a frozen stock of M. smegmatis and grown overnight to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1. Stock solutions of test compounds in acetone (0.02–0.1 mM) were prepared, and batches of 20 μL of such solutions were added to 250 μL of the bacterial suspensions in 1.73 mL of 7H9 media in 5 mL culture tubes. The tubes were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. The MIC values were then determined by reading the OD600 of the suspensions with different concentrations of the test compounds. To ensure that no viable bacteria remained in such tubes was confirmed as follows. Aliquots of 100 μL of the suspensions were added to fresh 7H9 media (1 mL) and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. In all cases, no bacteria growth was observed. The MIC results are summarized in Table 3, and all concentrations were performed in triplicate.

Table 3. MIC (μM) Values for Activity Against M. smegmatis.

| compound | MIC (μM) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 60 |

| 2 | >100 |

| 3 | >100 |

| [ClAu(PPh3)] | 60 |

| PZA | >100 |

| INH | 80 |

M. tuberculosis

A stock culture of M. tuberculosis was prepared by inoculation of a 1 mL frozen stock into 50 mL of Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) OADC enrichment (BBL Middlebrook OADC, 212351), 0.5% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.05% (w/v) Tween 80 (P1754, Sigma-Aldrich) in a roller bottle. Cells were grown to an OD600 of 1.0 to begin the experiments. The culture was then diluted down to a target OD600 of 0.5 (final OD reading = 0.67). Aliquots of 100 μL of 8 mM test compound solutions in acetone were added to batches of 10 mL of the culture suspension (final concentration of the test compounds = 80 μM in 1% acetone) and the tubes were then incubated at 37 °C. After 24 h incubation, the OD600 values were recorded. Triplicates were run with each test compound, and the results are shown in Figure 5.

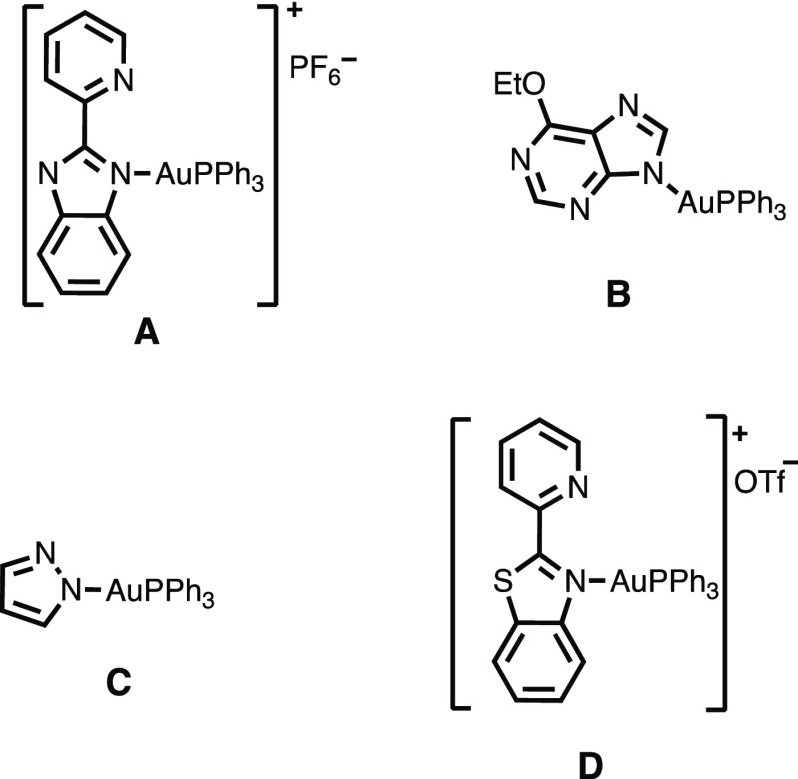

Figure 5.

M. tuberculosis OD600 values of the initial (day 0) and after 24 h (day 1) incubation with test compounds at 80 μM. Column C has no additional compound and acetone (Ace).

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

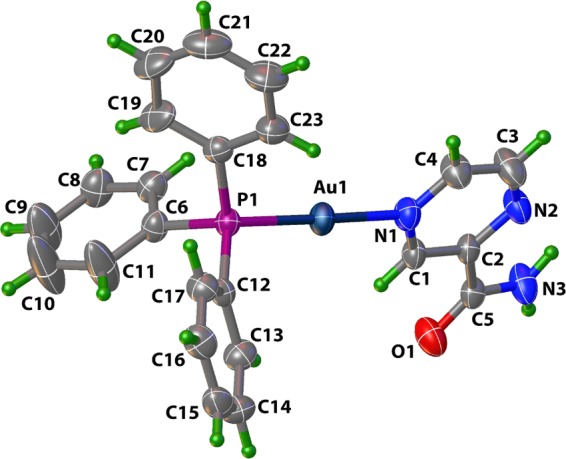

Complex 1 was synthesized by first displacing the chloride ligand from [ClAu(PPh3)] with the aid of Ag(OTf) and introducing PZA as the second ligand. Single-crystal analysis of 1 (Figure 2) revealed PZA as a monodentate N-donor ligand.24 The IR spectrum of 1 exhibits a strong peak centered around 1261 cm–1 corresponding to the OTf counterion and the carbonyl amide peak of PZA at 1690 cm–1.

Figure 2.

Structure of 1 with water and OTf anion omitted for clarity. Ellipsoids are shown at the 50% probability level.

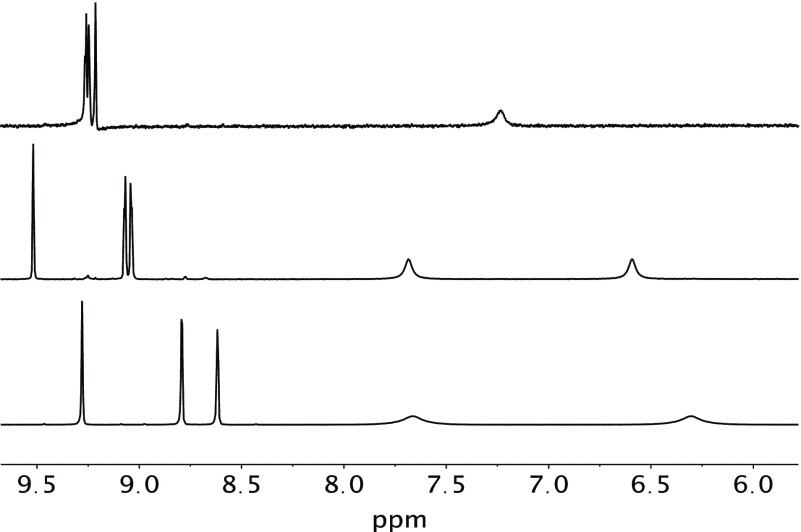

Complex 2 (Figure 3, top panel) was not obtained from the initial reaction of KAuCl4 and PZA. That reaction afforded the precursor complex (mentioned above). This precursor complex as shown in Scheme 1 is always the first product that appears as a bright yellow solid and behaves similarly to the analogous [AuCl3(pyrazine)] complex.25 Slow evaporation of the methanolic solution of this precursor complex eventually affords complex 2. Comparison of the IR spectra of the precursor complex and 2 reveals different νCO frequencies (1704 and 1660 cm–1, respectively) corresponding to the amide CO group of PZA. Because the νCO of the precursor complex is close to the νCO value of free PZA (1711 cm–1), we believe that in this complex the PZA ligand is bound to the Au(III) center in a monodentate fashion (as shown in Scheme 1). In complex 2, the PZA ligand is bonded as a bidentate ligand (Figure 3) with the deprotonated amide group. Elimination of HCl from the precursor complex leads to formation of complex 2 in methanolic solution upon long evaporation (Scheme 1). Due to the relatively quick reaction time (10 min), the precursor material presumably precipitates out as the kinetically favored species while 2 is the thermodynamically favored species obtained after recrystallization from methanol. The assignment is further supported by the fact that while the precursor complex exhibits two amide NH peaks in its NMR spectrum (much like free PZA) in CD3CN, complex 2 displays only one NH peak in its NMR spectrum in the same solvent (Figure 4). Also the precursor complex, like [AuCl3(pyrazine)], readily loses the N-donor ligand in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-d6 (as evidenced by NMR spectra).25 We hypothesize that in the precursor complex, PZA is bound to the Au(III) center at the N atom meta to the carboxamide group (as observed in complex 1) simply because this N center is the most basic site of the PZA molecule.26 Conversion of the precursor complex to 2 is accelerated by the addition of NaHCO3 in a 1:1 MeOH/water reaction mixture, a step that pushes the reaction shown in Scheme 1 to the right.

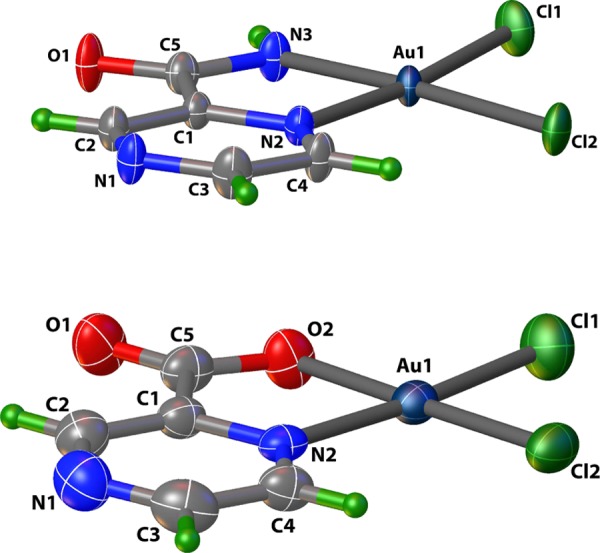

Figure 3.

Crystal structures of 2 (top) and 3 (bottom) with thermal ellipsoids at 50% probability.

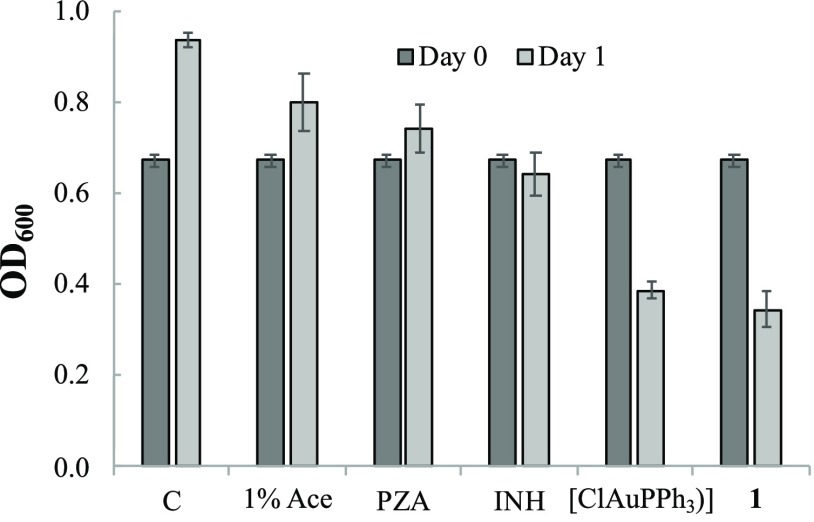

Scheme 1. Suggested Ligand Binding Mode Rearrangement from the Precursor Complex (Left) to 2.

Figure 4.

1H NMR (in CD3CN) spectra of 2 (top), the precursor compound (middle), and PZA (bottom).

PZO, the purported metabolic product actually responsible for the drug action of PZA, also binds the Au(III) center as a bidentate ligand (Figure 3, bottom panel). Addition of excess deprotonated PZO to KAuCl4 in the aqueous medium affords complex 3 in high yield.

Structures

Structures of 1–3 were characterized by X-ray crystallography and the perspective views (with atom labeling schemes) are shown in Figures 2 and 3, while the structure refinement parameters and selected bond distances and angles are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. For the sake of comparison of the metric parameters, the two Au(III) complexes (2 and 3) are shown in Figure 3. As evident from their crystal structures, the Au(I) complex 1 exhibits a linear coordination, while the two Au(III) complexes are square planar. In the structure of 1, there is one molecule of water in the asymmetric unit, while the other two structures contain no solvent of crystallization. The N(1)–Au(1)–P(1) angle in 1 deviates slightly from linearity with an angle of 177.8(2)°. The Au–N(pyridine) (2.081(7) Å) bond is shorter than Au–P (2.244(2) Å) bond as expected. Similar bond lengths and angles are observed in other known structures of Au(I) complexes of [(N-bound ligand)Au(PPh3)]-type.11,14 The three nitrogen atoms on PZA potentially allow for three different binding modes to the {Au(PPh3)}+ unit in 1; however, the least sterically hindered and most basic N of PZA shows preference to the metal center, as shown in Figure 1.26

Table 2. Selected Bond Lengths and Angles for 1·H2O, 2, and 3.

| 1·H2O | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Au(I)–P(1) | 2.2432 (18) | ||

| Au(I)–N(1) | 2.082 (6) | ||

| Au(I)–N(3) | 1.985 (4) | ||

| Au(I)–N(2) | 2.042 (4) | 2.016 (6) | |

| Au(1)–Cl(1) | 2.2571 (12) | 2.250 (2) | |

| Au(1)–Cl(2) | 2.2879 (12) | 2.2510 (17) | |

| Au(1)–O(2) | 1.998 (4) | ||

| N(1)–Au(1)–P(1) | 177.8 (2) | ||

| N(3)–Au(1)–Cl(1) | 93.22 (12) | ||

| N(2)–Au(1)–N(3) | 80.51 (16) | ||

| Cl(1)–Au(1)–Cl(2) | 90.75 (5) | 90.68 (7) | |

| N(2)–Au(1)–Cl(2) | 95.63 (11) | 95.57 (14) | |

| N(2)–Au(1)–O(2) | 82.7 (2) | ||

| O(2)–Au(1)–Cl(1) | 91.01 (16) |

Au(III) complexes 2 and 3 are both distorted square planar and composed of the PZA/PZO ligand bound as a bidentate ligand. The square planar geometries of 2 and 3 deviate noticeably from planarity with N(2)–Au(1)–N(3) and N(2)–Au(1)–O(2) angles of 80.51(16) and 82.7(2)°, respectively. The Cl(1)–Au(1)–Cl(2) angles of both structures deviate only slightly from the perfect right angle values 90.75(5) and 90.68(7)°, respectively. As expected, the deprotonated Au(1)–N(3) or Au(1)–O(2) of 2 and 3 are significantly shorter than the Au(1)–N(2) bonds shown in Table 2. Bond lengths and angles are in agreement with similar known structures of Au(III)-picolinamide and picolinic acid derivatives.27,28

In 2, the equatorial plane comprised of Au(1), N(2), N(3), Cl(1), Cl(2) atoms is fairly planar with a mean deviation of 0.041(3) Å, while the corresponding plane in 3 (comprised of Au(1), O(2), N(2), Cl(1), Cl(2) atoms) is highly planar with a mean deviation of 0.011(3) Å. The central metal atom in 2 and 3 is deviated from these planes by 0.009(3) and 0.022(3) Å, respectively. The two chelate planes formed by the bidentate PZA and PZO ligands along with Au(III) centers in 2 (Au(1), N(2), N(3), C(1), and C(5)) and 3 (Au(1), N(2), O(2), C(1), and C(5)) exhibit minimal deviation from planarity (mean deviations, 0.01(3)1 and 0.019(3) Å for 2 and 3, respectively). The dihedral angles between the pyrazine ring and the five-membered chelate ring in 2 and 3 are 3.18(2) and 1.83(2)°, respectively. In an Au(III) complex with picolinamide as a ligand, which structurally resembles closely to that of complex 2, the dihedral angle between the pyridine ring and the five-membered chelate ring is 3.6(2)°, which is close to the corresponding value noted for 2.27 Moreover, the mean deviations of the chelate ring are similar to those in 2. However, a reported Au(III) complex with a picolinic acid derivative as the ligand resembles structurally more to complex 3, and the dihedral angle between the pyridine ring and the five-membered chelate ring is 1.28(2)°.28

Mycobacterial Activity

Before studying the potential synergistic effects of PZA and gold on M. tuberculosis, the antimicrobial effects of the Au center alone were studied on M. smegmatis. This bacterium is in the same genus as M. tuberculosis and has 2000 genes highly conserved with the pathogen. Thus, M. Smegmatis is an excellent model organism that is easy to work with, has a fast growth rate, and a relatively safer model.23,29M. Smegmatis is known to be naturally resistant to PZA and thus provides an opportunity to study the activity of the {Au(I)(PPh3)}+ and {Au(III)Cl2}+ moieties of 1–3. In the present work, the activities of 1–3, [ClAu(PPh3)], PZA, and a drug control isoniazid (INH) were tested against M. smegmatis in a normal growth environment and the results are summarized in Table 3. Under our conditions, we found the MIC to be 60 μM for 1 and [ClAu(PPh3)], while 2, 3, and PZA showed no activity up to 100 μM. Mycobacteria species are known to have thick, hydrophobic, and waxy membranes that prevent foreign substances from permeation more so than traditional Gram-positive and Gram-negative species.30,31 For this reason, the lipophilic {Au(PPh3)}+ unit in 1 might have been able to pass through this membrane and exert drug action. This conclusion is supported by the fact that cell digests from M. smegmatis cells exposed to 40 μM (below the MIC) of 1 exhibited strong inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) signal(s) for gold. Also, the gold(III) species 2 and 3 with chloro ligands but no {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety were not active at similar concentrations.

With results from M. Smegmatis study in hand, we proceeded to test the activity of complex 1 against M. tuberculosis in vitro along with [ClAu(PPh3)], PZA, and isoniazid (INH). The OD of M. tuberculosis was recorded after 24 h incubation with 80 μM of each compound in 1% acetone (Figure 5). Interestingly, 1 showed significant bactericidal activity (reduction in OD), while PZA on its own was only mildly bacteriostatic (OD less than the control but higher than day 0). The mild drug action of PZA against M. tuberculosis at the 80 μM concentration is expected since the higher concentration of PZA (up to 400 μM) and low pH (5.5) media are usually required to observe any effect on M. tuberculosis growth in vitro.32 The results shown in Figure 5 strongly suggest that the {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety of 1 augments the efficacy of PZA in vitro. The standard [ClAu(PPh3)] was specifically included in this study to determine if 1 would show increased activity compared to a compound with the {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety without PZA. Inspection of Figure 5 reveals that both 1 and [ClAu(PPh3)] exhibited the greatest reduction in OD at very similar average values of 0.345 and 0.387, respectively. Collectively, these results suggest that complex 1 could introduce a dose of PZA as well as the {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety in one combination and act as a “two-in-one” drug against M. tuberculosis. Ultimately, this might reduce the need for much higher doses of PZA itself, which has severe side effects on humans. The gold–phosphine unit is not so uncommon in metallodrug therapy; Auranofin, an FDA-approved drug for rheumatoid arthritis, does contain a {Au(PEt3)}+ unit.4

PZA plays an important role in shortening TB treatment duration from 9–12 months to 6 months. This is likely because PZA targets a population of semidormant bacilli residing within the macrophages in an environment not accessible to other TB drugs.32,33 The mechanism of action of the pro-drug PZA is not entirely understood, but most agree that the conversion of PZA to PZO within the bacilli is critical for activity against M. tuberculosis. Interestingly, PZO itself is not as active as PZA against M. tuberculosis. PZA has a broad range of activity highly dependent on the pH of the media and because it targets mostly nonreplicating bacilli, PZA exhibits slow or no bactericidal activity in vitro.32 This occurrence is likely the reason why no synergy was observed in our hands. Nevertheless, PZA has had a significant clinical impact on TB and therefore research toward modifying PZA with the additional antimycobacterial moiety might lead to new and improved outcomes.

Solution studies

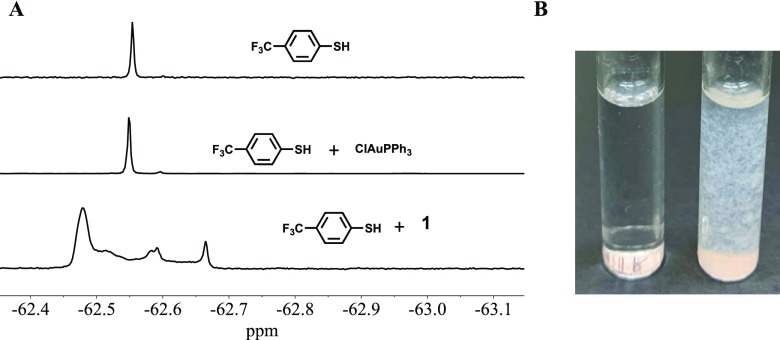

The results of 1H NMR studies confirm that 1–3 are stable in acetone, while 2 and 3 are also stable in acetonitrile. Complexes 2 and 3 are stable in aqueous acetone (90:10) for hours, while 1 slowly decomposes in such solutions (used in biological studies). However, inside biologically relevant environments, exposure to sulfur-containing biomolecules like glutathione is expected. Gold(I) centers are soft Lewis acids, and it is well established that they prefer binding to soft Lewis bases like thiolate species. The binding of gold(I) species to biologically relevant thiols (such as glutathione) and enzymes with thiol-containing active sites (such as thioredoxin) has been observed and the exchange of N- and S-bound ligands occurs quickly compared to P-bound ligands.14,34 This exchange has been hypothesized to play an important role in the anticancer effects of [N–Au(PPh3)] complexes14 as well as the antimycobacterial effects exhibited by auranofin.35 Disruption of redox homeostasis within the bacterial cell following binding of the gold unit to glutathione or thioredoxin has been suggested to be responsible for the drug action. Impairment of protein synthesis in bacteria has also been observed with auranofin treatment.36 In our previous work, we have showed that complexes with N-bound benzothiazole ligands and the {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety rapidly exchange with thiol species.11 In the present work, we checked the possibility of exchange between PZA and biologically relevant thiols in the case of 1. Both 1H and 19F NMR spectra of the mixture of 1 and 4-(trifluoromethyl)thiophenol (FTP) were recorded to observe if PZA does get exchanged with FTP (Figure 6). As shown in Figure 6 (left panel), addition of FTP to 1 showed release of PZA as a free ligand (as evident in the 1H NMR, not shown) with multiple new 19F NMR peaks (Figure 6A, bottom) along with a white precipitate. Together, these results indicate the formation of {S–Au(PPh3)}-polymeric species by 1 in the presence of a thiol. We hypothesize that such a transformation will lead to the presence of both PZA and {Au(PPh3)}+ units, which will exert their own individual and potentially synergistic actions. In contrast, [ClAu(PPh3)] does not appear to react with FTP and form any Au–thiol species (Figure 6A, middle panel). In the acidic (pH 6.2–4.5) macrophage compartment,37 replacement of Cl– by a thiol is highly unlikely. Thus, administration of 1 (compared to [ClAu(PPh3)]) could be more reactive against M. tuberculosis residing within the macrophages in vivo. We have also employed a more biologically relevant thiol, namely, N-acetyl l-cysteine methyl ester, to check this interpretation. Addition of N-acetyl l-cysteine methyl ester to 1 resulted in the immediate appearance of a white precipitate (Figure 6B, right), but no such reaction was observed with [ClAu(PPh3)] (Figure 6B, left). Collectively, these results suggest that formation of {S–Au(PPh3)}-polymeric species with 1 within biological targets might promote uptake by host macrophages, similar to the uptake of Au nanoparticles38,39 and/or breakdown of cellular thiol-redox homeostasis.35 Since M. tuberculosis is either contained by macrophages or reside within them, this process could offer a more direct route to TB treatment in a host system. The {S–Au(PPh3)}-polymeric species derived from 1, along with PZA, could cause more damage to the mycobacterium residing within the macrophages and thus increasing the efficacy of the treatment.

Figure 6.

(A) F19 NMR spectra of HSC6H4CF3 (top), [ClAu(PPh3)] + HSC6H4CF3 (middle), and 1 + HSC6H4CF3 (bottom). (B) Reaction of [ClAu(PPh3)] (left) and 1 (right) after addition of N-acetyl-l-cysteine-methyl-ester.

Conclusions

While Au complexes have been evaluated for their antimycobacterial effects previously,40−43 extensive literature search reveals only two other complexes containing the {Au(PPh3)}+ unit (Figure 7) in such testing.15,16 Also, in a previous study, the auranofin containing PEt3 moiety has been shown to exert potent activity against M. tuberculosis.35 Between the two complexes with the {Au(PPh3)}+ unit, the one with the acridine moiety as a ligand (Figure 7, left) was screened against M. tuberculosis, while the other with sulfadiazine as a ligand (Figure 7, right) was tested against other members of the mycobacterium genus. The sulfadiazine–Au(PPh3) complex showed synergy of the sulfadiazine antibiotic with the {Au(PPh3)}+ unit. We expect that similar synergy between PZA and the {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety (arising from 1) could increase the efficacy of the treatment compared to PZA alone under in vitro conditions.

Figure 7.

Au Complexes with the {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety that have been evaluated for their antimycobacterial activity.15,16

Current TB treatment regimens require four orally taken drugs (PZA, ethambutol, rifampicin, isoniazid) at high dosages for 6 months with the daily dose of PZA recommended at 30 mg/kg for at least 2 of those months.17 Much of the difficulty of treatment for this disease arises from both the inherent thick, waxy mycomembrane (preventing foreign substances from permeation) of M. tuberculosis and the success to survive within host macrophages.30,31 Complexes like 1, as evidenced by our results, may react immediately with biologically relevant thiols to produce free PZA and {Au(PPh3)–thiol} polymeric species. The {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety of 1 may provide the lipophilicity required to pass through the mycomebrane to exert its action, while a dose of PZA is also provided simultaneously. So far, the success of PZA in the TB treatment has been an extremely valuable finding; further investigation into the possible synergistic effects between PZA (or other TB drugs) and the {Au(PPh3)}+ moiety in vivo could be valuable toward identifying new drugs, especially for future treatment of emerging drug-resistant strains. Such studies are in progress in this laboratory.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from a UCSC COR Grant and the DMR Grant 1409335 from NSF is gratefully acknowledged. R.O. received support from the NIH IMSD Grant 2R25GM058903.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c00071.

Crystallographic Data (CIF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Pricker S. P. Medical Uses of Gold Compounds: Past, Present and Future. Gold Bull. 1996, 29, 53–60. 10.1007/BF03215464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benedek T. G. The History of Gold Therapy for Tuberculosis. J. Hist. Med. Allied Sci. 2004, 59, 50–89. 10.1093/jhmas/jrg042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish R. V.; Cottrill S. M. Medicinal Gold Compounds. Gold Bull. 1987, 20, 3–12. 10.1007/BF03214653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faa G.; Gerosa C.; Fanni D.; Lachowicz J. I.; Nurchi V. M. Gold - Old Drug with New Potentials. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 75–84. 10.2174/0929867324666170330091438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortego L.; Gonzalo-Asensio J.; Laguna A.; Villacampa M. D.; Gimeno M. C. Aminophosphane Gold(I) and Silver(I) Complexes as Antibacterial Agents. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015, 146, 19–27. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glišić B. Đ.; Djuran M. I. Gold Complexes as Antimicrobial Agents: An Overview of Different Biological Activities in Relation to the Oxidation State of the Gold Ion and the Ligand Structure. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 5950–5969. 10.1039/C4DT00022F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott I. On the Medicinal Chemistry of Gold Complexes as Anticancer Drugs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 1670–1681. 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nardon C.; Boscutti G.; Fregona D. Beyond Platinums: Gold Complexes as Anticancer Agents. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 487–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messori L.; Abbate F.; Marcon G.; Orioli P.; Fontani M.; Mini E.; Mazzei T.; Carotti S.; O’Connell T.; Zanello P. Gold(III) Complexes as Potential Antitumor Agents: Solution Chemistry and Cytotoxic Properties of Some Selected Gold(III) Compounds. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 3541–3548. 10.1021/jm990492u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomiya K.; Noguchi R.; Ohsawa K.; Tsuda K.; Oda M. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Antimicrobial Activities of Two Isomeric Gold(I) Complexes with Nitrogen-Containing Heterocycle and Triphenylphosphine Ligands, [Au(L)(PPh3)] (HL = pyrazole and Imidazole). J. Inorg. Biochem. 2000, 78, 363–370. 10.1016/S0162-0134(00)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenger-Smith J.; Chakraborty I.; Mascharak P. K. Cationic Au(I) Complexes with Aryl-Benzothiazoles and Their Antibacterial Activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 185, 80–85. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serratice M.; Bertrand B.; Janssen E. F. J.; Hemelt E.; Zucca A.; Cocco F.; Cinellu M. A.; Casini A. Gold (I) Compounds with Lansoprazole-type Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization and Anticancer Properties in vitro. Med. Chem. Commun. 2014, 5, 1418–1422. 10.1039/C4MD00241E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serratice M.; Cinellu M. A.; Maiore L.; Pilo M.; Zucca A.; Gabbiani C.; Guerri A.; Landini I.; Nobili S.; Mini E.; Messori L. Synthesis, Structural Characterization, Solution Behavior, and in Vitro Antiproliferative Properties of a Series of Gold Complexes with 2-(2′-Pyridyl)Benzimidazole as Ligand: Comparisons of Gold(III) versus Gold(I) and Mononuclear versus Binuclear Derivat. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 3161–3171. 10.1021/ic202639t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Křikavová R.; Hošek J.; Vančo J.; Hutyra J.; Dvořák Z.; Trávníček Z. Gold(I)-Triphenylphosphine Complexes with Hypoxanthine-Derived Ligands: In Vitro Evaluations of Anticancer and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. PLoS One 2014, 9, e107373 10.1371/journal.pone.0107373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiter L. C.; Hall N. W.; Day C. S.; Saluta G.; Kucera G. L.; Bierbach U. Gold(I) Analogues of a Platinum–Acridine Antitumor Agent Are Only Moderately Cytotoxic but Show Potent Activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6519–6522. 10.1021/jm9012856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agertt V. A.; Bonez P. C.; Rossi G. G.; da Costa Flores V.; dos Santos Siqueira F.; Mizdal C. R.; Marques L. L.; de Oliveira G. N. M.; de Campos M. M. A. Identification of Antimicrobial Activity among New Sulfonamide Metal Complexes for Combating Rapidly Growing Mycobacteria. BioMetals 2016, 29, 807–816. 10.1007/s10534-016-9951-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotgiu G.; Centis R.; D’Ambrosio L.; Migliori G. B. Tuberculosis Treatment and Drug Regimens. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a017822 10.1101/cshperspect.a017822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North A. C. T.; Phillips D. C.; Mathews F. S. A Semiempirical Method of Absorption Correction. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A 1968, 24, 351–359. 10.1107/S0567739468000707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. SHELXT - Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov O. V.; Bourhis L. J.; Gildea R. J.; Howard J. A. K.; Puschmann H. OLEX2: A Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. 10.1107/S0021889808042726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M.SHELXTL TM (V 6.14); Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems: Madison, WI, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. K.; Reyrat J.-M. Laboratory Maintenance of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. 2009, 14, 10C.1.1–10C.1.12. 10.1002/9780471729259.mc10c01s14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H.; Sengupta S.; Petersen J. L.; Akhmedov N. G.; Shi X. Triazole–Au(I) Complexes: A New Class of Catalysts with Improved Thermal Stability and Reactivity for Intermolecular Alkyne Hydroamination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 12100–12102. 10.1021/ja9041093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warżajtis B.; Glišić B. D.; Radulović N. S.; Rychlewska U.; Djuran M. I. Gold(III) Complexes with Monodentate Coordinated Diazines: An Evidence for Strong Electron-Withdrawing Effect of Au(III) Ion. Polyhedron 2014, 79, 221–228. 10.1016/j.poly.2014.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabanda M. M.; Tran V. T.; Tran Q. T.; Ebenso E. E. A Computational Study of Pyrazinamide: Tautomerism, Acid-Base Properties, Micro-Solvation Effects and Acid Hydrolysis Mechanism. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2014, 1046, 30–41. 10.1016/j.comptc.2014.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill D. T.; Burns K.; Titus D. D.; Girard G. R.; Reiff W. M.; Mascavage L. M. Dichloro(Pyridine-2-Carboxamido-N1,N2)Gold(III), a Bis-Nitrogen Aurocycle: Syntheses, Gold-197 Mossbauer Spectroscopy, and X-Ray Crystal Structure. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2003, 346, 1–6. 10.1016/S0020-1693(02)01425-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dar A.; Moss K.; Cottrill S. M.; Parish R. V.; McAuliffe C. A.; Pritchard R. G.; Beagley B.; Sandbank J. Complexes of Gold(III) with Mononegative Bidentate N,O-Ligands. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1992, 1907–1913. 10.1039/dt9920001907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catanho M.; Mascarenhas D.; Degrave W.; de Miranda A. B. GenoMycDB: A Database for Comparative Analysis of Mycobacterial Genes and Genomes. Genet. Mol. Res. 2006, 5, 115–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton M. J.; Vermeulen M. W. Immunopathology of Tuberculosis: Roles of Macrophages and Monocytes. Infect. Immun. 1996, 64, 683–690. 10.1128/IAI.64.3.683-690.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado D.; Girardini M.; Viveiros M.; Pieroni M. Challenging the Drug-likeness Dogma for New Drug Discovery in Tuberculosis. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1367 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Mitchison D. The Curious Characteristics of Pyrazinamide: A Review. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2003, 7, 6–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Scorpio A.; Nikaido H.; Sun Z. Role of Acid PH and Deficient Efflux of Pyrazinoic Acid in Unique Susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to Pyrazinamide. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 2044–2049. 10.1128/JB.181.7.2044-2049.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw C. F.; Coffer M. T.; Klingbeil J.; Mirabelli C. K. Application of a 31P NMR Chemical Shift: Gold Affinity Correlation to Hemoglobin-Gold Binding and the First Inter-Protein Gold Transfer Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 729–734. 10.1021/ja00211a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harbut M. B.; Vilchèze C.; Luo X.; Hensler M. E.; Guo H.; Yang B.; Chatterjee A. K.; Nizet V.; Jacobs W. R.; Schultz P. G.; Wang F. Auranofin Exerts Broad-Spectrum Bactericidal Activities by Targeting Thiol-Redox Homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 112, 4453–4458. 10.1073/pnas.1504022112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangamani S.; Mohammad H.; Abushahba M. F. N.; Sobreira T. J. P.; Hedrick V. E.; Paul L. N.; Seleem M. N. Antibacterial Activity and Mechanism of Action of Auranofin against Multi-Drug Resistant bacterial pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22571 10.1038/srep22571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandal O. H.; Nathan C. F.; Ehrt S. Acid Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 4714–4721. 10.1128/JB.00305-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- França A.; Aggarwal P.; Barsov E. V.; Kozlov S. V.; Dobrovolskaia M. A.; González-Fernández Á. Macrophage Scavenger Receptor A Mediates the Uptake of Gold Colloids by Macrophages in Vitro. Nanomedicine 2011, 6, 1175–1188. 10.2217/nnm.11.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R.; Nawale L.; Arkile M.; Wadhwani S.; Shedbalkar U.; Chopade S.; Sarkar D.; Chopade B. A. Phytogenic Silver, Gold, and Bimetallic Nanoparticles as Novel Antitubercular Agents. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 1889–1897. 10.2147/IJN.S102488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanye S. D.; Wan B.; Franzblau S. G.; Gut J.; Rosenthal P. J.; Smith G. S.; Chibale K. Synthesis and in Vitro Antimalarial and Antitubercular Activity of Gold(III) Complexes Containing Thiosemicarbazone Ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 3392–3396. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2011.07.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuin A.; Massabni A. C.; Pereira G. A.; Leite C. Q. F.; Pavan F. R.; Sesti-Costa R.; Heinrich T. A.; Costa-Neto C. M. 6-Mercaptopurine Complexes with Silver and Gold Ions: Anti-Tuberculosis and Anti-Cancer Activities. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2011, 65, 334–338. 10.1016/j.biopha.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira G. A.; Massabni A. C.; Castellano E. E.; Costa L. A. S.; Leite C. Q. F.; Pavan F. R.; Cuin A. A Broad Study of Two New Promising Antimycobacterial Drugs: Ag(I) and Au(I) Complexes with 2-(2-Thienyl)Benzothiazole. Polyhedron 2012, 38, 291–296. 10.1016/j.poly.2012.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R.; Felix C. R.; Akerman M. P.; Akerman K. J.; Slabber C. A.; Wang W.; Adams J.; Shaw L. N.; Tse-Dinh Y. C.; Munro O. Q.; et al. Evidence for Inhibition of Topoisomerase 1a by Gold(III) Macrocycles and Chelates Targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium abscessus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01696 10.1128/AAC.01696-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.